Cultural Consumption and Citizen Engagement—Strategies for Built Heritage Conservation and Sustainable Development. A Case Study of Indore City, India

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How can consumer participation and citizen engagement be involved in the preservation of local built heritage?

- What key approaches emerge as pivotal for diverse stakeholder engagement and inclusive strategy creation for built heritage preservation?

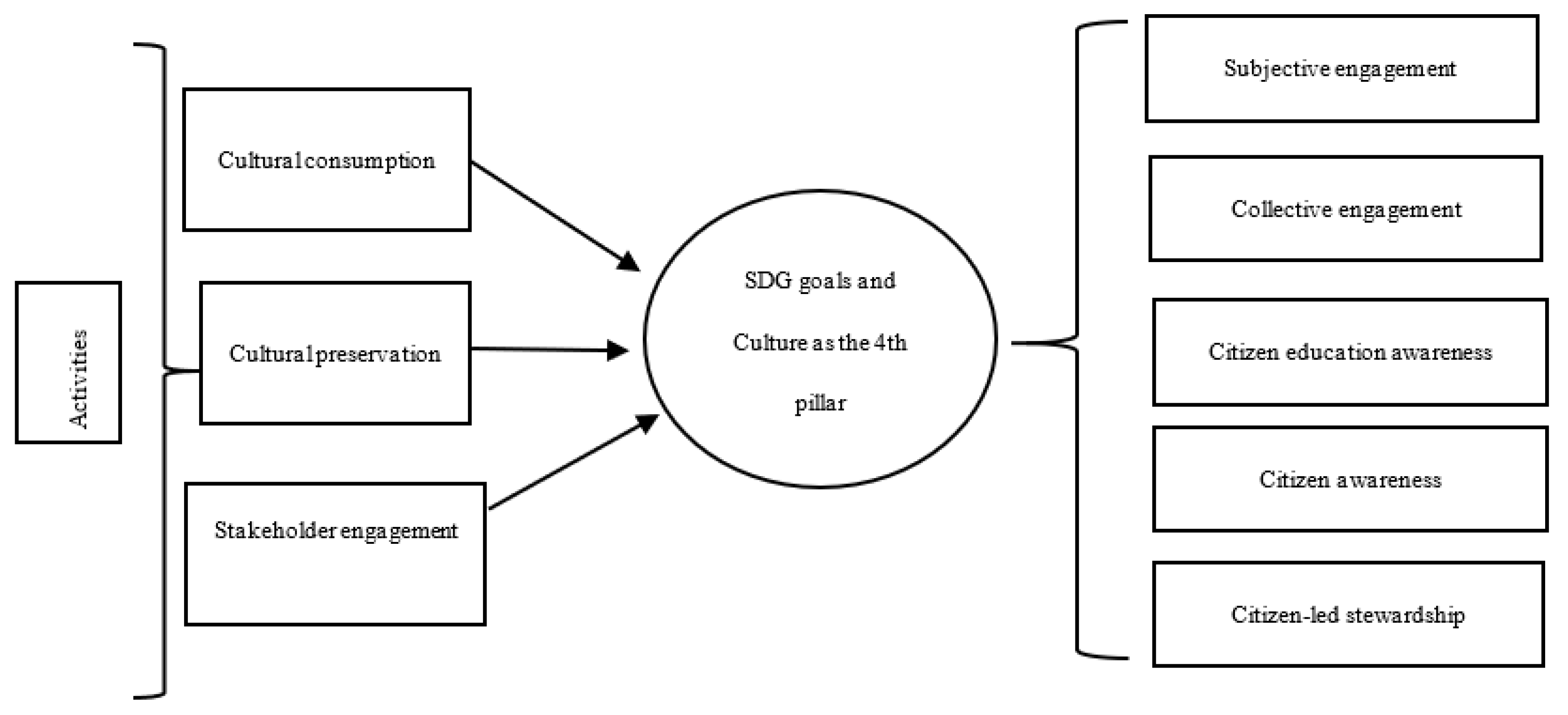

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Culture-Based Sustainable Development

2.2. Cultural Heritage and Consumption

2.3. Cultural Heritage and Stakeholders

3. Empirical Context—Indore City and Strategies for Built Heritage

3.1. Indore

3.2. Built Heritage Conservation

3.3. City Identity

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Approach One: Citizen Consultation

- The first phase consisted of setting the agenda and goals. Nearly 250,000 citizens were connected with in a sector-wise manner and were engaged in discussions and decisions regarding the area-wise development to map out priorities and relevant resources.

- In the second phase, the focus was the finalisation of the area, pan-city, based on citizen’s preferred areas for development. In this round, nearly 180,000 citizen interactions were achieved.

- The third and final round involved approximately 170,000 citizen contacts and the objective was to draft a plan for the Smart City proposal as approved by the citizens.

4.2. Approach Two: Partnership with External Funding Agencies

4.3. Approach Three: Student Engagement and Participation from Educational Institutions

4.4. Approach Four: Participation from Stakeholders/Companies

5. Analysis of the Strategic Approaches

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Herskovits, M.J. Man and His Works, the Science of Cultural Anthropology; Alfred A. Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Cetina, K.K. Culture in global knowledge societies: Knowledge cultures and epistemic cultures. Interdiscip. Sci. Rev. 1949, 32, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department for Economic and Social Affairs. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2016. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Irandu, E.M. The role of tourism in the conservation of cultural heritage in Kenya. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2004, 9, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wearing, S.; Schweinsberg, S.; Darcy, S. Consuming our national parks. In Cultural Heritage; Campelo, A., Reyolds, L., Lindgreen, A., Beverland, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury, N.; Cullen, C.; Pascual, J. Cities, culture and sustainable development. In Cultural Policy and Governance in a New Metropolitan Age; Anheier, H., Isar, Y.A., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2012; pp. 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Brocchi, D. The Cultural Dimension of Sustainability. In Sustainability: A New Frontier for the Arts and Culture; Kagan, S., Kirchberg, V., Eds.; Verlag für Akademische Schriften: Frankfurt, Germany, 2008; pp. 26–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hosagrahar, J. Culture: At the Heart of SDGs. 2019. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/courier/april-june-2017/culture-heart-sdgs (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Zhang, R.; Smith, L. Bonding and dissonance: Rethinking the interrelations among stakeholders in heritage tourism. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najd, M.D.; Ismail, N.A.; Maulan, S.; Yunos, M.Y.M.; Niya, M.D. Visual preference dimensions of historic urban areas: The determinants for urban heritage conservation. Habitat Int. 2019, 49, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.G. Authenticity as a challenge in the transformation of Beijing’s urban heritage: The commercial gentrification of the Guozijian historic area. Cities 2019, 59, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hooimeijer, P.; Lin, Y.; Geertman, S. Strategies of the built heritage stewardship movement in urban redevelopment in the Internet Age: The case of the Bell-Drum Towers controversy in Beijing, China. Geoforum 2019, 106, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, S.; Berglund, K.; Gunnarsson, E.; Sundin, E. Promoting Innovation-Policies, Practices, and Procedures. 2012. Available online: https://www.vinnova.se/contentassets/b2ada2f4b62840a4ba05e77e31f8665f/vr_12_08.pdf (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Throsby, D. Cultural capital. J. Cult. Econ. 2019, 23, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, R.; Piracha, A. Cultural frameworks. In Urban Crisis: Culture and the Sustainability of Cities; Nadaraja, M., Yamamoto, A.T., Eds.; United Nations University Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2007; pp. 13–50. [Google Scholar]

- Nurse, K. Culture as the fourth pillar of sustainable development. Small States Econ. Rev. Basic Stat. 2019, 11, 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Culture for Urban Sustainable Development (UNESCO). 2019. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/en/culture/themes/culture-and-development/culture-for-sustainable-urban-development/ (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- Sustainable Development Goals. 2030. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Verdini, G.; Ceccarelli, P. (Eds.) Creative small settlements. In Culture-Based Solutions for Local Sustainable Development; Research Report; University of Westminster: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, B. Heritage as knowledge: Capital or culture? Urban Stud. 2019, 39, 1003–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tour. Manag. 2019, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulding, C. Romancing the past: Heritage visiting and the nostalgic consumer. Psychol. Mark. 2019, 18, 565–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y.; Ashworth, G. Heritage tourism—Current resource for conflict. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 36, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chronis, A. Our Byzantine heritage: Consumption of the past and its experiential benefits. J. Consum. Mark. 2005, 22, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McArthur, S.; Hall, C.M. Heritage Management in Australia and New Zealand: The Human Dimension; Oxford University Press: Melbourne, Auckland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Valentina, V.; Marius-Răzvan, S.; Login, I.A.; Anca, C. Changes in cultural heritage consumption model: Challenges and Limits. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2005, 188, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt, R.A. Culturally and ecologically sustainable tourism development through local community management. In Culture and Sustainable Development in the Pacific; Hooper, A., Ed.; ANU E Press and Asia pacific Press: Canberra, Australia, 2005; pp. 174–187. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Zapata, J.D.; Espinal-Monsalve, N.E.; Herrero-Prieto, L.C. Economic valuation of museums as public club goods: Why build loyalty in cultural heritage consumption? J. Cult. Herit. 2005, 30, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeho, A.J.; Prentice, R.C. Evaluating the experiences and benefits gained by tourists visiting a socio-industrial heritage museum: An application of ASEB grid analysis to Blists hill open-air museum, the Ironbridge Gorge Museum, United Kingdom. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2005, 14, 229–251. [Google Scholar]

- Otnes, C.C.; Maclaran, P. The consumption of cultural heritage among a British Royal Family brand tribe. In Consumer Tribes; Cova, B., Kozinets, R., Shankar, A., Eds.; Butterworth-Heineman: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Cova, B.; Cova, V. Tribal marketing: The tribalisation of society and its impact on the conduct of marketing. Eur. J. Mark. 2002, 36, 595–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cang, V.G. Defining intangible cultural heritage and its stakeholders: The case of Japan. Int. J. Intang. Herit. 2002, 2, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Joyce, R.A. Academic freedom, stewardship and cultural heritage: Weighing the interests of stakeholders in crafting repatriation approaches. In The Dead and Their Possessions; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2002; pp. 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Burghausen, M.; Balmer, J.M.T. Corporate heritage identity stewardship: A corporate marketing perspective. Eur. J. Mark. 2015, 49, 22–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, J. Re-gendering governance. In Remaking Governance Peoples, Politics and the Public Sphere; Newman, J., Ed.; Polity Press: Bristol, UK, 2015; pp. 81–99. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, E. A reflexive exploration of two qualitative data coding techniques. J. Methods Meas. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G. Open coding descriptions. Grounded Theory Rev. 2016, 15, 108–110. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, H. Content analysis of secondary data: A study of courage in managerial decision making. J. Bus. Ethics 2001, 34, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Census India 2011, Madhya Pradesh, District Census Handbook, Indore. 2015. Available online: https://censusindia.gov.in/2011census/dchb/DCHB_A/23/2322_PART_A_DCHB_INDORE.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- Singh, R.P. Geography and Politics in Central India: A Case Study of Erstwhile Indore State; Concept Publishing Company: New Delhi, India, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- History and Heritage. 2020. Available online: https://www.smartcityindore.org/history-heritage/ (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- Swach Sarvekshan Survey, the World’s Largest Cleanliness Survey. 2019. Available online: http://www.swachhsurvekshan2020.org/Images/SS2019%20Report.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- Smart City Mission Transformation. 2015. Available online: https://smartnet.niua.org/sites/default/files/resources/smartcityguidelines.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- Request for Proposal “Conservation, Restoration and Redevelopment of Malhar Rao Holkar Chatri, Chattri Bagh Indore”. Available online: https://smartnet.niua.org/sites/default/files/malhar_rao_holkar.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- Indore District Map. 2021. Available online: https://www.mapsofindia.com/maps/madhyapradesh/districts/indore.htm (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- Presentation on Smart City Proposal—Indore. 2020. Available online: https://smartnet.niua.org/sites/default/files/resources/Indore_SmartCity.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- Indore Smart City Development Limited, Request for Proposal Conservation, Restoration & Adaptive reuse of Gopal Mandir Complex, Indore (Phase I). 2017. Available online: https://smartnet.niua.org/sites/default/files/TENDERDOCGOPALMANDIR.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- Preservation and Beyond. 2020. Available online: https://www.wmf.org/what-we-do (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Madhya Pradesh Cultural Heritage Project. 2020. Available online: https://www.wmf.org/project/madhya-pradesh-cultural-heritage-project (accessed on 31 January 2020).

- Preserving Heritage of Indore, INTACH Initiative. 2017. Available online: https://news.globalindianschool.org/indore/preserving-heritage-of-indore-intach-initiative (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- Indore Smart City Facebook Page. 2021. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/IndoreSmartCityOfficial/photos/ (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- IndiGo. 2020. Available online: https://www.goindigo.in/about-us.html?linkNav=about-us_footer (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Restoration of Lal Baug Palace, Indore. 2020. Available online: https://www.goindigo.in/csr/heritage/restoration-of-historic-interiors.html (accessed on 10 November 2020).

| SDG Goal | Name of the Goal | The Implication for Cultural Heritage |

|---|---|---|

| 11 | To make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. | Protecting global and local natural and built heritage to promote the growth and development of related cultural and creative industries. |

| 17 | To revitalise the global partnership for sustainable development. | Proposes that the knowledge regarding the importance of cultural preservation will empower local communities and trigger the conscious consumption of cultural heritage. |

| 8 | To foster decent work and economic growth. | Local cultural heritage is placed to not only instigate local industry and job opportunities but also encourage inbound tourism and micro-entrepreneurship. |

| 4 | To work towards quality education. | Local communities, when strong in the knowledge of their cultural heritage, can develop inroads into local businesses and create employment opportunities, while also enriching their ecosystems around the appreciation and implementation of cultural diversity. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Billore, S. Cultural Consumption and Citizen Engagement—Strategies for Built Heritage Conservation and Sustainable Development. A Case Study of Indore City, India. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2878. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052878

Billore S. Cultural Consumption and Citizen Engagement—Strategies for Built Heritage Conservation and Sustainable Development. A Case Study of Indore City, India. Sustainability. 2021; 13(5):2878. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052878

Chicago/Turabian StyleBillore, Soniya. 2021. "Cultural Consumption and Citizen Engagement—Strategies for Built Heritage Conservation and Sustainable Development. A Case Study of Indore City, India" Sustainability 13, no. 5: 2878. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052878

APA StyleBillore, S. (2021). Cultural Consumption and Citizen Engagement—Strategies for Built Heritage Conservation and Sustainable Development. A Case Study of Indore City, India. Sustainability, 13(5), 2878. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052878