Abstract

The past research on radicalism is equivocal regarding the ways in which self-concept clarity shapes intentions to engage in radical behavior. Seeking to address the previous mixed findings in the literature, the present research examines how an individual’s agency-communion orientation moderates the effect of self-concept clarity on behavioral intentions for radical groups. Specifically, we propose that agency-oriented individuals show greater intentions to participate in radical groups when they experience low (vs. high) self-concept clarity, whereas communion-oriented individuals show no significant differences in their intentions to participate in radical groups across levels of self-concept clarity. A 2 (agency-communion orientation: low vs. high) × 2 (self-concept clarity: low vs. high) experimental design was used to test the hypotheses. Using gender as a proxy variable for agency-communion orientation, Study 1 shows that agency-communion orientation moderates the effect of self-concept clarity on intentions to participate in radical groups. Using chronic individual differences in agency-communion orientation, Study 2 shows that psychological entitlement mediates the interactive effect of self-concept clarity and agency-communion orientation on behavioral intentions for radical groups. Taken together, these findings support the role of agency-communion orientation and self-concept clarity in radicalism.

1. Introduction

Radicalism is a serious social issue in today’s society. Radical movements in Islamic State (IS) have claimed a number of innocent victims under the name of protecting its religious beliefs from Christian influence. One deadly manifestation of the radicalism was the November 2015 Paris attack, in which several popular spots in Paris became the target of shootings, hostage takings, and suicide bombings. As such, radicalism places many people’s lives in danger, and the social costs of public unrest caused by radicalism can be high enough to hinder sustainable economic growth. Thus, the investigation of the conditions in which people are likely to engage in radical actions is important with regard to achieving a better and more sustainable future.

As such, we may ask what the factors are that lead to greater inclination towards radicalism. Research has shown that people are likely to fall into radicalism when they feel a sense of low efficacy towards a focal issue [1,2], or when the emotion of contempt is evoked in reaction to a controversial issue [3]. In addition to these antecedents, a lack of self-concept clarity is associated with increased support for radicalism and aggressive behavior [4,5]. According to uncertainty–identity theory [6], when people feel their self-concept is inconsistent or incoherent, they attempt to regain self-concept clarity by identifying with groups which can provide them with clear identities. In this respect, radical groups are more advantageous than other groups because radical attitudes and behaviors are often not supported by the majority, and its distinctiveness can give its members the benefits of being easily distinguished from out-group members.

As such, an important question arises: does a lack of self-concept clarity always lead to increased support for radicalism? Radical groups use means that are aggressive in nature; thus, participation in radical groups poses a significant risk of being isolated from the whole society. In addition, the tactics used by radical groups are extreme in nature, which in turn could seriously damage other innocent people. As such, those who have a concern for others may not resort to radicalism even under the state of an unclear self-concept. Indeed, there is a mixed finding regarding the effect of low self-concept clarity on behavioral intentions for radical groups [4].

In this article, we propose an overarching framework that can provide an integrative account for when and why low levels of self-concept clarity lead to heightened behavioral intentions for radical groups. Specifically, we will show that individuals’ agency-communion orientation plays a moderating role in the effect of self-concept clarity on behavioral intentions for radical groups. Agency and communion correspond to the two fundamental modalities of human nature, namely, the perspective of the self and the perspective of others. Agentic content is primarily related to goal achievement and task functioning, and it is associated with the male stereotype. Conversely, communal content is primarily related to the maintenance of relationships and social functioning, and it is associated with the female stereotype [7,8].

The present research contributes to self-concept literature by extending our understanding of self-concept uncertainty in radicalism. Although other studies have focused on the role of an unclear self-concept in increased radical behavior [9,10], little attention has been paid to the moderating role of motivational differences in such process. The present research extends the research by focusing on the individual difference variable of agency-communion orientation.

The paper is structured as follows. First, we review the literature on self-concept clarity, and its connections with uncertainty–identity theory and identification with radical groups. Then, we propose the theoretical framework and the main hypotheses. We report the results of two studies which test our hypotheses. Finally, we conclude by discussing the theoretical and practical implications, limitations, and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Self-Concept Clarity

When we think about our life for a moment, it becomes clear that life is full of uncertainties. For instance, college students are uncertain whether they will be able to find a decent job after graduation, and researchers are uncertain whether their paper submitted to a top-notch journal will be accepted or rejected. Uncertainty refers to the state in which individuals have less information available than they ideally would like to have in order to make social judgments [11]. There are many different types of uncertainties, among which one of great importance is uncertainty about one’s self-concept. This is because one’s self-concept serves as an integrative framework for one’s perceptions, cognitions, and behaviors [12].

The self-concept refers to a cognitive schema that stores information about values, traits, and memories about the self [13]. An individual’s self-concept is divided into (1) its contents and (2) the structural aspects of one’s self-concept. Self-concept clarity is defined as the extent to which people have a consistent, coherent, and stable self-concept [14]. Self-concept clarity taps into (1) the temporal stability and (2) the internal consistency of one’s self-view. Having a clear self-concept is associated with positive outcomes such as high self-esteem [14], whereas the lack of a clear self-concept is associated with negative outcomes, such as low self-esteem, low agreeableness, and high neuroticism [14,15,16]. Thus, being in a state of low self-concept clarity generates uncomfortable feelings, and is eventually considered aversive [17].

Since lacking clarity in one’s self-concept is an aversive state, individuals who have low self-concept clarity are motivated to engage in behaviors that can bolster and clarify their self-concept. Such behaviors range from compensatory convictions (e.g., the bolstering of one’s attitude on social issues [18]) to compensatory purchasing behavior (e.g., the purchase of self-expressive products [19]). According to the distinctive principle, people base the identity of themselves and others less on attributes that are common, and more on attributes that are different [20,21], so these tendencies reflect individuals’ attempts to maximize self–other differences. Another way in which individuals can boost their self-concept clarity is to identify with groups with clear attributes, which will be discussed in detail in the next section.

2.2. Uncertainty–Identity Theory and Identification with Radical Groups

As noted earlier, the lack of a clear self-concept is aversive, and people who suffer from a low self-concept clarity have a strong drive to clarify their self-concept. One way in which people can regain self-concept clarity is by identifying with a group that is relevant to the self [6,22]. According to uncertainty–identity theory, group identification provides an effective means of bolstering one’s self-concept clarity, because group prototypes can serve as a guide for who they are and how they should behave. This process is accompanied by the social categorization of the self and others—depersonalizing the self and adjusting one’s behavior and attitudes to group norms. Adhering to group norms enables individuals to gain a better understanding of who they are and how they should behave.

What type of groups do individuals prefer to identify with when they suffer from a lack of self-concept clarity? Previous studies have shown that some types of groups are more effective than others in clarifying self-concept via group identification. For instance, high-entitative groups—which involve groups with clear boundaries, internal homogeneity, and a clear structure and goals [23]—are more likely to help individuals regain a clearer self-concept than difficult-to-distinguish groups; thus, identifying with such groups helps individuals regain a clearer self-concept. Indeed, Hogg et al. [24] have shown that people are more likely to identify with high- than low-entitative groups when their self-concept is rendered unclear.

When the lack of self-concept clarity is intense, individuals may feel a stronger need to regain a sense of self-concept clarity, and may even be inclined to identify with groups with radical behavioral tactics. Radicalism pertains to the behavioral dimension of a group: radical groups are more oriented towards assertively, quickly, and decisively dealing with a threat [25]. The nature of a radical group—focusing on actions rather than words—may serve as an antidote to those who suffer from low self-concept clarity. Indeed, Hogg, Meehan and Farquharson [4] showed that a lack of self-concept clarity may lead to a greater intention to participate in radical groups. In this study, college students read information about an issue which most students would disagree with: a proposal that students would have to pay their tuition fees upfront rather than after they graduate. Then, the participants were asked to think about how such a change in tuition fee reforms would make their lives more certain (uncertain), depending on self-concept clarity conditions. After the priming of high (vs. low) self-concept clarity, participants watched a 4-minute video interview with a student action group which is committed to fighting against the issue. The interview content differed across group radicalism conditions; under the high radicalism condition, the action group was described as having extreme behavioral agenda, focusing on radical tactics in order to attain its goal of having the proposal withdrawn. In contrast, the action group under the low radicalism condition was described as pursuing its objective in a moderate fashion, focusing on political means rather than direct ones. It was found that the participants’ greater identification with moderate (vs. radical) groups disappeared under low self-concept clarity conditions. Other researchers have also examined the negative association between self-concept clarity and the endorsement of extreme attitudes and behaviors [9,26].

However, being involved in radicalism has many disadvantages. Radicalism, by its nature, is minor in a society. Thus, members of radical groups are likely to suffer from feelings of isolation, and have greater chances of facing hate comments and rage from the majority [27]. In addition, radicalism itself creates substantial problems in our society. For instance, the Paris attack in 2015 ended up leaving hundreds of casualties who had little association with the cause the terrorists wanted to claim. Thus, individuals who are more oriented towards others may not pursue such radical means in order to clarify their self-view.

As is consistent with this assumption, previous research has documented equivocal findings regarding individuals’ tendency to conform to radical beliefs and groups when they have a low self-concept clarity. Indeed, engaging in radical actions is beneficial in that it can show the identities that deviate from mainstream society, such that those who are innately oriented towards themselves can reap sufficient benefits by participating in such a group. However, radical groups might not fit well with those who are more focused on others, valuing harmonious relationships. In the next section, we will explain how this might be moderated by individuals’ self–other orientations, i.e., agency-communion orientation.

2.3. The Moderating Role of Agency-Communion Orientation

In his seminal article, Bakan [28] proposed two basic modes of human existence—agency and communion. Agency reflects a focus on one’s own self, whereas communion pertains to a focus on others. Agency is associated with separating the self from others, and agency-oriented individuals value traits such as being competitive, ambitious and powerful. In contrast, communion is associated with forming connections with others, and these individuals value traits such as being warm, compassionate, and generous [29].

Research has shown that individuals’ agency-communion orientations lead to different motivational orientations. Agency-oriented individuals have concern for themselves, and they desire to stand out from the groups to which they belong. As such, when agency-oriented individuals feel threatened, they tend to avoid such feelings by distancing themselves from others. In other words, agentic individuals have a desire to express their individuality, and this tendency leads them to become more religious in secular countries. Conversely, communion-oriented individuals have a concern for others, and they desire to observe social norms and stay in harmony with the groups to which they belong. Accordingly, when communion-oriented individuals are threatened, they seek to restore their connections with others, and they are more likely to be religious when living a religious life is the social norm [30,31].

As such, how would individuals’ agency-communion orientation influence their intentions to engage in radical actions when their self-concept is rendered unclear? Having a low self-concept clarity is uncomfortable for all individuals, but the means by which they pursue the goal of clarifying their self-view may be dependent on their agency-communion orientation. As noted earlier, identifying with a group with notable characteristics can give individuals opportunities to strengthen their self-concept clarity by projecting the group’s attributes and characteristics onto one’s self. Radical groups are advantageous in this process because their aggressive behavioral tactics and strategies can help individuals build a clearer self-concept by distinguishing themselves from out-group members. The highly aggressive and distinctive nature of radical groups would be desirable to agency-oriented individuals with low self-concept clarity. Agentic individuals are motivated to differentiate themselves from others; thus, participating in radical groups is consistent with their goal of enhancing their self-concept clarity. Communion-oriented individuals, however, may regard such characteristics of radical groups as undesirable when their self-concept clarity is rendered unclear. This is because the radical group’s aggressiveness is inconsistent with communion-oriented individuals’ tendency to maintain harmonious relationships with others. Consequently, communal individuals may not show greater intentions to participate in radical groups when they desire to clarify their self-view.

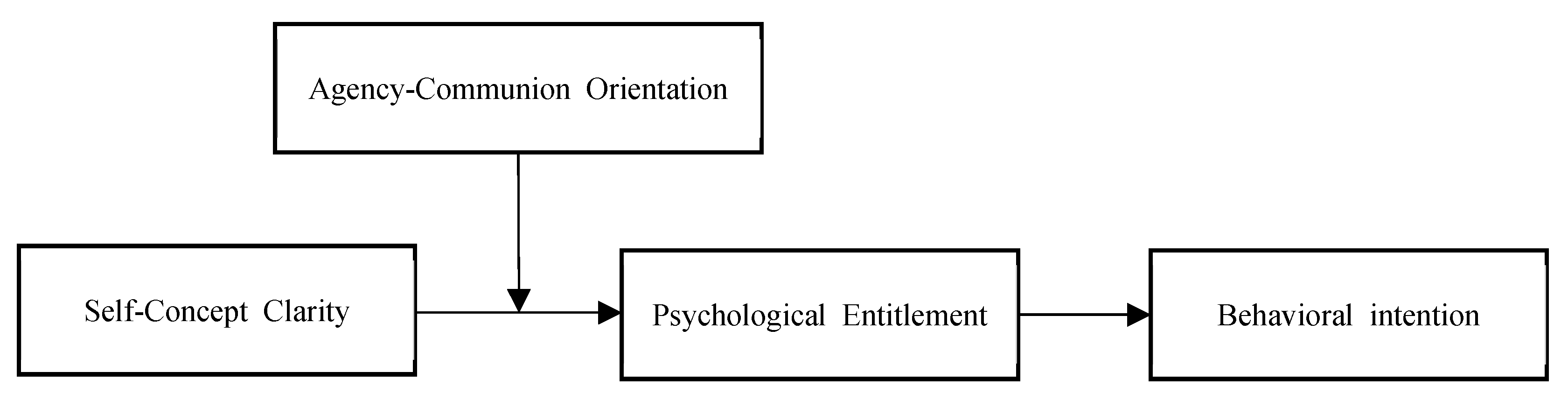

As such, what accounts for such differential preferences for radical groups between agency- and communion-oriented individuals in response to low self-concept clarity? We propose that psychological entitlement accounts for the differential reactions towards threats to self-concept clarity. Psychological entitlement refers to the stable and pervasive sense that one deserves more and is entitled to more than others [32]. It is documented that psychological entitlement is a component of narcissism, which is characterized by “grandiose self-views and a relentless addiction-like striving to continually assert their self-worth and superiority” [33]. Research shows that narcissists build their grandiose self-views by forming unrealistically positive self-evaluations regarding agency (e.g., competence, power, uniqueness) traits rather than communion (e.g., warmth, agreeableness, harmony) traits [34]. From this, we expect that agency-oriented individuals would exhibit greater psychological entitlement compared to communion-oriented individuals. These differences in psychological entitlement would in turn affect behavioral intentions for radical groups. As noted earlier, engaging in radical actions is beneficial in enhancing self-concept clarity to a large extent, but its aggressiveness poses significant threats to others and society as a whole. Because agency-oriented individuals think of themselves as deserving more than others (i.e., high psychological entitlement), they would be more likely to focus their attention on the positive side (enhanced self-concept clarity) of joining radical groups, which will lead to greater behavioral intentions for such groups. In contrast, communion-oriented individuals do not think of themselves as deserving more than others, and they would be more likely to focus on the negative side (posing risk to others and society) of joining radical groups. Accordingly, their intentions to participate in radical groups would not differ in terms of their levels of self-concept clarity. Combining these predictions results in the following hypotheses (as illustrated in Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Conceptual Framework.

Hypotheses 1 (H1).

Agency-oriented individuals show greater intentions to participate in radical groups when their self-concept clarity is low (vs. high).

Hypotheses 2 (H2).

Communion-oriented individuals’ behavioral intentions towards radical groups are not significantly different between low and high self-concept clarity conditions.

Hypotheses 3 (H3).

Psychological entitlement mediates the interactive effect of agency-communion orientation and self-concept clarity on behavioral intentions for radical groups.

3. Experiment

3.1. Study 1

The goal of Study 1 was to show initial evidence that agency-communion orientation moderates the effect of self-concept clarity on intentions to participate in radical groups. In Study 1, we operationalized agency-communion orientation as gender. This is consistent with Bakan’s [28] suggestion that agency orientation tends to pertain to males, whereas communion orientation is more characteristic of females. Indeed, there is a substantial literature that used gender as a proxy for agency-communion orientation [35,36,37]. In line with hypotheses 1 and 2, we predict that agentic individuals (i.e., males) would show greater intentions to participate in radical groups when their self-concept clarity is threatened (vs. not threatened), whereas communal individuals (i.e., females) would not show significant differences in behavioral intentions across levels of self-concept clarity.

3.1.1. Study Design

Ninety three participants (46 women, 47 men; age range: 18 to 65 years) were recruited from Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk website. The participants were randomly assigned to either the low (N = 49) or the high (N = 44) self-concept clarity condition. The participants were from four major states of the United States—California, Texas, Florida, and Illinois—and they were paid $1.0 for participation in this study. The state factor does not have a significant effect on any of the dependent variables we measured, and thus will not be discussed further.

3.1.2. Procedure

The participants read an instruction that they would be participating in two short, unrelated studies: one on a reflection of the self and one on the evaluation of a social group. In the first session, the participants were asked to reflect on themselves. The content of the thoughts they should recall was dependent on the condition to which each participant belonged. The participants in the low self-concept clarity condition were asked to recall a time when they felt conflicted and unsure about particular traits or aspects of themselves, whereas those in the high self-concept-clarity condition were asked to recall a time when they felt clear and sure about particular traits or aspects of themselves [19]. Then, they were asked to describe such situations in as much detail as possible, e.g., what happened and how they felt, etc.

In the second session, the participants were told that they would evaluate a civil organization that fights a proposed sales tax increase. First, they read information about an issue of a sales tax increase proposal. Specifically, the participants were told that the state in which they live is considering a sales tax increase because of its huge budget deficit, and this increase would set their state as the state with the highest state sales tax rate in the United States. Then, the participants were told that many non-governmental organizations (NGOs) showed public disapproval over this issue. After reading this information, participants indicated their own opinion on this issue via a one-item scale: “I agree with this tax increase”, “I disagree with this tax increase”, or “I neither agree nor disagree with this tax increase”. Only the participants who were against the tax increase (i.e., those who chose “I disagree with this tax increase”) were used for further analysis.

Then, the participants read a brief introduction of a social group which is against the proposed tax increase. This social group was named ‘Taxpayers’ Associations of (state name)’, in which each participant’s background state was used for the naming. This group was described as “being dedicated to protecting the rights of average taxpayers”, and “firmly opposing the proposed sales tax increase in (state name)”. In addition, in order to emphasize its highly radical nature of the group, the participants read the following statement:

We stand up against this proposed sales tax increase in (state name), and will take strong direct actions to convince the public that this proposal should be withdrawn, even if it means breaking the law. Specifically, we will rest on direct methods, and organize protest campaigns that might involve the use of violent means.

After reading the information about the group, the participants completed the dependent measures and were debriefed. Specifically, they were told that the issue of a sales tax increase and the information about the social group was prepared only for research purposes.

3.1.3. Measures

All of the dependent variables were measured on seven-point scales anchored by 1 and 7.

- Behavioral intentions: the participants indicated their behavioral intentions for the social group via four-item scales. Specifically, they were asked how likely it would be that they would participate in each of four activities for the group: join the group, donate money to the group, volunteer their time working for the group, or support the group. These items were averaged to form a behavioral intention index (α = 0.958).

- Perceived self-concept clarity: the participants completed a three-item self-concept clarity scale, which assesses the stability and consistency of the self (e.g., “My beliefs about myself often conflict with one another” [14]). These items were averaged to form a perceived self-concept clarity index (α = 0.930).

- Group normativity: the participants reported how normative they perceive the social group’s actions to be [3]. The definition of normative actions was provided as follows: “Actions are normative when they are supported by the majority and when they are in line with conventions and rules. In contrast, actions are non-normative when they are not supported by the majority and when they violate conventions and rules”. Then, the participants indicated their perception of the group’s proposed actions via a one-item scale anchored by “Tactics used by [group name] are absolutely non-normative” and “Tactics used by [group name] are absolutely normative”.

3.1.4. Results

Manipulation check.

As expected, the participants in the low self-concept clarity condition reported lower self-concept clarity (Mlow = 2.570, SD = 1.20) compared to those in the high self-concept clarity condition (Mhigh = 5.13, SD = 1.15; F(1,91) = 85.62, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.48). In addition, the participants perceived the focal group as being more non-normative than normative, and this did not vary as a function of self-concept clarity (Mlow = 5.72 vs. Mhigh = 5.57, F(1,91) = 0.224, non-significant).

Hypothesis Testing.

A 2 (gender: male vs. female) × 2 (self-concept clarity: low vs. high) analysis of variance (ANOVA) on the behavioral intention index revealed only a significant effect of gender × SCC (self-concept clarity) interaction (Table 1) (F(1,91) = 4.69, p < 0.04, η2 = 0.049)). No other significant effects were found. We conducted a planned-contrast analysis to test our hypotheses. As predicted, the male participants whose self-concept clarity was rendered low showed greater intentions to participate in the social group than those whose self-concept clarity was rendered high (Mlow = 2.97 vs. Mhigh = 2.06, F(1,47) = 3.53, p < 0.07, η2 = 0.070). In contrast, the behavioral intentions of the female participants did not differ across levels of self-concept clarity (Mlow = 2.32 vs. Mhigh = 3.03, F(1,42) = 1.52, non-significant). This confirms H1 and H2.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations of behavioral intentions, Study 1.

3.1.5. Discussion

The result of Study 1 provides support for the moderating role of agency-communion orientation in the relationship between self-concept clarity and behavioral intentions for the focal group. Specifically, our findings indicate that low self-concept clarity elevates intentions to participate in radical groups only when individuals are agency-oriented (i.e., males). When the individuals were communion-oriented (i.e., females), self-concept clarity did not have a significant impact on behavioral intentions for radical groups. This result is consistent with H1a and H1b, which suggests that low (vs. high) self-concept clarity boosts support for radical groups only when individuals are agency oriented.

One may wonder whether the group normativity used in Study 1 really captures group radicalism. Indeed, in real life, radical groups are non-normative, but not all non-normative groups are radical. However, previous research that investigated radical group behavior operationalized group radicality by the normativity of the means through which the group expresses their opinion [3,38]. For instance, in the context of student protests against tuition fees, Becker, Tausch and Wagner [3] distinguished moderate actions (e.g., participating in demonstrations, signing a petition) from radical actions (e.g., disturbing an event where the advocates of tuition fees appeared, blocking the highway) by assessing the normativity of each action. Moreover, Wright et al. [39] referred to collective non-normative action as “directly threatens the existing social order” (p. 995), which is also consistent with the definition of radicalism.

Study 1’s finding has limitations that deserve attention. In Study 1, gender was used as a proxy for agency-communion orientation. However, this effect of gender may not be fully attributed to differences in agency-communion orientation. Thus, Study 2 directly measures the individual differences in individuals’ agency-communion orientation. In addition, Study 1 did not show the process by which agency-communion orientation moderates the effect of self-concept clarity in behavioral intentions for radical groups. Thus, Study 2 will shed light on the mediating role of psychological entitlement.

3.2. Study 2

The purpose of Study 2 is to show additional evidence that agency-communion orientation moderates the effect of self-concept clarity on intentions to participate in radical groups. Specifically, we aim to show that an individual’s chronic differences in agency-communion orientation would also moderate the effect of self-concept clarity on behavioral intention.

More importantly, Study 2 demonstrates that individuals’ psychological entitlement accounts for the differential effect of agency-communion orientation on behavioral intentions for radical groups. As noted earlier, agency-communion orientation pertains to the ways in which people set priorities in pursuing their goals. Specifically, agency-oriented individuals are more focused on themselves, and place an emphasis on values such as power, status, and competence. On the other hand, communion-oriented individuals are more focused on others, and place an emphasis on values such as warmth, agreeableness, and harmony. These differences in the pursuit of the focal goal would also affect individuals’ views of themselves vis-a-vis others. In particular, agency-oriented individuals are more focused on themselves, and this perspective would result in seeing themselves as more important than others (high psychological entitlement). In contrast, communion-oriented individuals are more focused on others, which would lead to perceptions that others are equally important (low psychological entitlement). These differences in psychological entitlement, in turn, would lead to differential levels of behavioral intentions for radical groups.

3.2.1. Study Design

In total, 103 participants (48 women, 55 men; age range: 18 to 65 years) were recruited from Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk website. The participants were randomly assigned to either the low (N = 48) or the high (N = 55) self-concept clarity condition. The participants were from four major states of the United States: California, Texas, Florida, and Illinois, and were paid $1.0 for participation in this study. The state factor does not have a significant effect on any of the dependent variables, and thus will not be discussed further.

3.2.2. Procedure

The procedures of Study 2 are identical to those of Study 1, except for a few modifications. In Study 2, we additionally measured psychological entitlement and individual differences in agency-communion orientations.

3.2.3. Measures

All of the other measures are identical to Study 1, with a few exceptions listed below:

- Agency-communion orientation: the participants indicated their agency-communion orientation by responding to 20 items regarding their personality [31]. In particular, the participants were asked “How well does each of the following generally describe you?” The agentic items consist of “adventuresome”, “ambitious”, “bossy”, “clever”, “competitive”, “dominant”, “leader”, “outgoing”, “rational”, and “wise”. The communal items were “affectionate”, “caring”, “compassionate”, “faithful”, “honest”, “kind”, “patient”, “sensitive”, “trusting”, and “understanding”. Those two sets of items were averaged to form the agency orientation (α = 0.862) and communion orientation index (α = 0.887).

- Psychological entitlement: the participants completed a nine-item psychological entitlement scale, which assesses their beliefs about their own entitlement [32]. Example items are “I deserve more things in my life” and “I feel entitled to more of everything”. These items were averaged to form a psychological entitlement index (α = 0.855).

3.2.4. Results

Manipulation check.

As expected, the participants in the low self-concept clarity condition reported lower self-concept clarity (Mlow = 3.17, SD = 1.31) compared to those in the high self-concept clarity condition (Mhigh = 5.24, SD = 1.07; F(1,101) = 43.67, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.30).

Hypothesis Testing.

A regression was used to test the hypotheses. The key dependent variable was behavioral intentions. We first calculated the relative agency orientation, ACDIF (Agency-Communion Difference), by subtracting each participants’ communion orientation index from agency orientation index. This ACDIF measure is useful in that it captures not only the direction but also the relative magnitude of each participant’s agency-communion orientation [36].

First, we regressed the participants’ behavioral intention index onto their self-concept clarity (SCC: −1 = low SCC, 1 = high SCC), ACDIF, and the SCC × ACDIF interaction term. The results showed the significant effects of the SCC × ACDIF interaction term (Table 2) (b = −0.254, SE = 0.112, t(99) = −2.259, p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Regression results for Study 2.

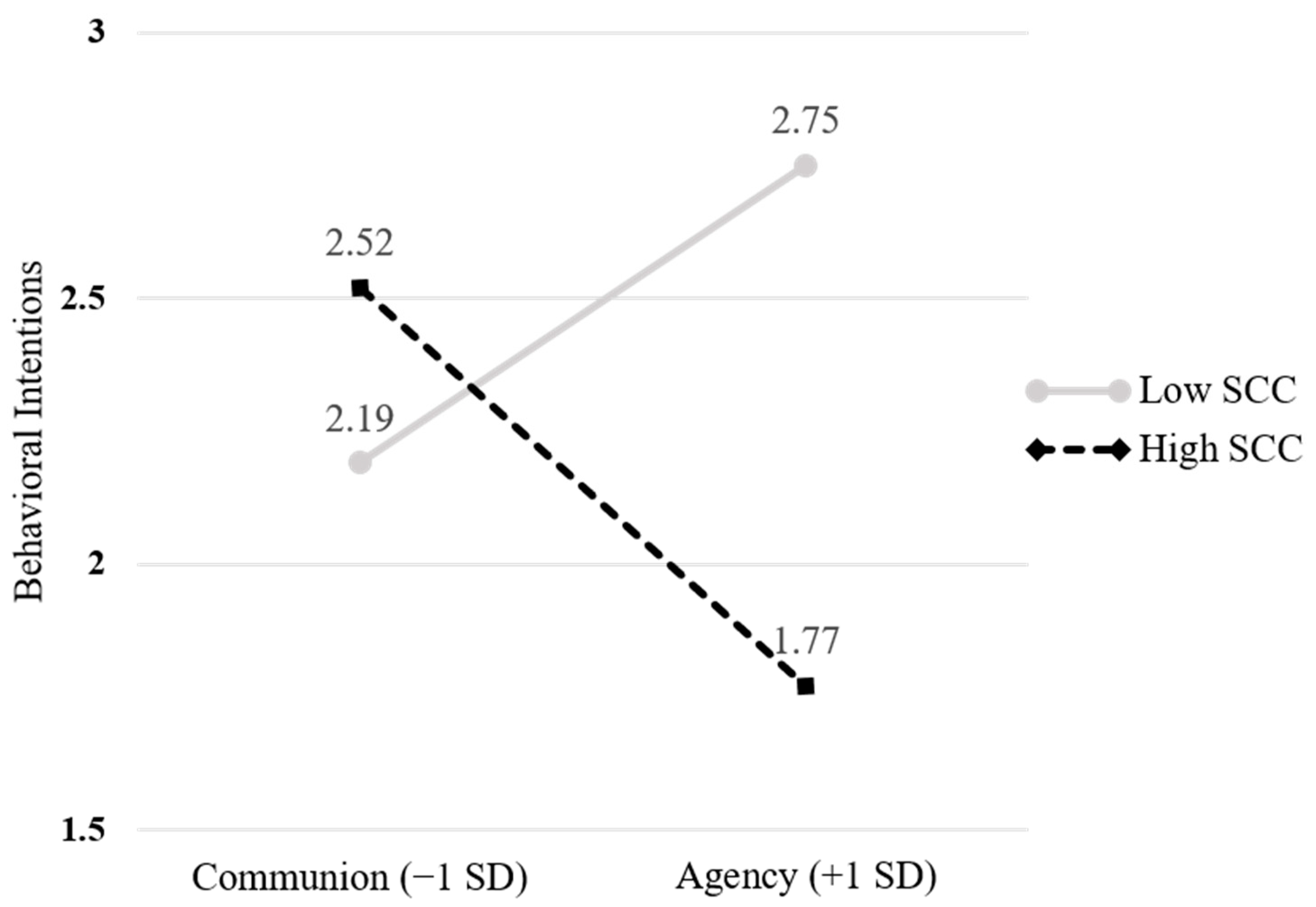

We conducted spotlight analyses to test our hypotheses. In order to examine the relationship, we reran the analysis with the ACDIF score centered at one standard deviation above (and below) the mean. In support of hypotheses 1a and 1b, in the agency-orientation condition (1 SD above the mean), the participants with low self-concept clarity showed greater behavioral intentions for radical groups compared with the participants with high self-concept clarity (b = −0.900, t(99) = 2.03, p < 0.05). However, in the communion-orientation condition (1 SD below the mean), self-concept clarity did not have a significant influence on behavioral intentions for radical groups (Figure 2) (b = 0.517, t(99) = −1.17, non-significant). This result again confirms H1a and H1b.

Figure 2.

Behavioral intentions as predicted by SCC and agency-communion orientation, Study 2.

We hypothesized that our results would be mediated by levels of psychological entitlement (H2). In order to test our hypothesis, we ran a mediation analysis using the PROCESS bootstrapping procedure [40]. In order to accomplish this, we set the SCC × ACDIF interaction as the independent variable, behavioral intentions as the dependent variable, and psychological entitlement as the mediator. As predicted, the indirect effect of the SCC × ACDIF interaction via psychological entitlement was significant (b = 0.311, SE = 0.113, 95% CI (0.086,0.535)), which indicates significant mediation. This confirms H2.

3.2.5. Discussion

The result of Study 2 again provides support for the moderating role of agency-communion orientation in the relationship between self-concept clarity and behavioral intentions for the focal group. In particular, our findings demonstrate that low (vs. high) self-concept clarity leads to greater intentions to participate in radical groups when individuals are chronically agency-oriented (i.e., a high ACDIF score). In contrast, when individuals are chronically communion-oriented (i.e., a low ACDIF score), the behavioral intentions for radical groups did not vary as a function of the individuals’ levels of self-concept clarity.

More importantly, Study 2 demonstrates the process by which agency-communion orientation moderates the effect of self-concept clarity on individuals’ behavioral intentions for radical groups. Specifically, our findings indicate that psychological entitlement mediates the interactive effect of self-concept clarity and agency-communion orientation on behavioral intentions for radical groups.

4. Discussion, Implication, and Conclusions

4.1. Discussion of the Results

The objective of the current research is to examine how individual’s agency-communion orientation moderates the effect of self-concept clarity on behavioral intentions for radical groups. Specifically, we aim to identify the condition under which self-concept clarity may or may not lead to greater intention to participate in radical groups. The results of the two experiments show that it is an individual’s agency-communion orientation that determines their proclivity toward radical actions: agency-oriented individuals in combination with low (vs. high) self-concept clarity are more likely to join radical groups (and their actions), while communion-oriented individuals are not likely to fall into radical actions even if their self-view is rendered unclear.

Study 1 showed that males exhibit greater intention to participate in a radical group when their self-concept clarity was low (vs. high), but females’ behavioral intentions are not affected by their self-concept clarity. Study 2 adds to the findings of Study 1 by showing that the individual differences in agency-communion orientation also moderate the effect of self-concept clarity on behavioral intentions for radical groups. Moreover, Study 2 demonstrated that psychological entitlement accounts for the interactive effect of self-concept clarity and agency-communion orientation on behavioral intentions for radical groups.

Our findings add to the previous literature on the role of self-concept clarity in radicalism by proposing the boundary conditions under which such an effect occurs. Although past studies have shown that individuals with low self-concept clarity are more inclined to resort to radical means than those with high self-concept clarity [4], relatively few efforts have been made to investigate the condition in which such effect is more pronounced. Our findings indicate that agency-communion orientation serves as a moderator. Specifically, agency-oriented individuals with low self-concept clarity are more likely to engage in radical behavior than those with high self-concept clarity, which is consistent with previous studies. However, the effect of self-concept clarity is attenuated among communion-oriented individuals.

4.2. Managerial and Academic Implications

The contributions of the current research are twofold. First, our research extends the literature on radicalism by demonstrating the moderating role of agency-communion orientation on people’s proclivity towards radical groups. Although previous research has shown boundary conditions in which a lack of self-concept clarity leads to greater endorsement towards radical groups (e.g., the self-relevance of the focal issue: Hogg and Adelman [9]), it did not provide evidence for the possibility that individuals’ agency-communion orientation might moderate such an effect. Our research addresses this gap by showing that only agency-oriented individuals show greater intentions for radical groups under low (vs. high) self-concept clarity. Second, our findings build on research on agency-communion orientation by showing another determining process of agency-communion orientation: the restoration of one’s self-concept clarity. The effect of agency-communion orientation on social judgment has been investigated for a variety of contexts, but it has been unknown whether or not agency-communion orientation would differentially affect individuals’ attempts to re-clarify their self-concept.

Managerially, our findings shed light on how firms should address their issues in times of corporate crises. When firms cause customer dissatisfaction, there is a chance that such dissatisfaction evolves into radical collective actions such as boycotting. Radical actions performed by angry customers may seriously damage a company’s reputation; thus, it is essential for firms to minimize the chances of the occurrence of such radical actions. The present research offers a way that can prevent such things from happening: exposure to communion-orientation primes. If consumers are led to adopt a communion-oriented perspective (e.g., a concern for others), they would take it into account that radical actions may run the risk of harming other innocent people, which in turn leads to a lower likelihood of engaging in such behavior.

4.3. Limitations

The present research has a few limitations. First, Study 1 used gender as a proxy for agency-communion orientation. Although agency-communion orientation is closely related to gender stereotypes [7], gender may not be fully attributed to differences in agency-communion orientation. Study 2 addressed this issue by directly measuring agency-communion orientation, and the result we obtained from Study 2 was consistent with that of Study 1. However, agency-communion orientation can be directly manipulated, but our study did not implement such manipulation. Thus, it would be valuable to manipulate agency-communion orientation in future studies.

In addition, we used a hypothetical tax increase scenario as the cover story for both studies. Although this scenario is consistent with the stimuli used in past research [4], the external validity could be improved by using different scenarios. Therefore, it would be meaningful to test our hypotheses in different contexts.

4.4. Future Studies and Recommendations

An avenue for future research lies in exploring the means which communal individuals would adopt when their self-concept clarity is momentarily lowered. As noted earlier, the state of having an unclear self-concept is aversive, so communal individuals may also set the goal of clarifying their self-view as their top priority. In such a case, communion-oriented individuals may enhance their self-concept clarity by strengthening their existing associations with other people. For instance, communal individuals may attempt to reestablish relationships with others who used to be close to them.

In addition, it would be fruitful to extend the current findings into other group contexts. For instance, highly entitative groups are beneficial in reducing uncertainty because of the clear identities they provide to their group members. Thus, it merits attention to investigate whether agency-communion orientation also moderates people’s preferences for high-entitative groups in the case of low self-concept clarity.

4.5. Concluding Remarks

Radicalization is a global phenomenon that causes devastating consequences for human lives. The results from previous studies indicate that clarifying one’s self-concept can serve as a means to protect society from radicalism. Our findings add to the literature by demonstrating that adhering to communion-oriented values can be effective when strengthening an individual’s self-concept is not easy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, investigation, H.C. and Y.Y.; methodology, H.C. and Y.Y.; draft writing, H.C.; supervision, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all of the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rottweiler, B.; Gill, P. Conspiracy beliefs and violent extremist intentions: The contingent effects of self-efficacy, self-control and law-related morality. Terror. Political Violence 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tausch, N.; Becker, J.C.; Spears, R.; Christ, O.; Saab, R.; Singh, P.; Siddiqui, R.N. Explaining radical group behavior: Developing emotion and efficacy routes to normative and nonnormative collective action. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 101, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.C.; Tausch, N.; Wagner, U. Emotional consequences of collective action participation: Differentiating self-directed and outgroup-directed emotions. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 37, 1587–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A.; Meehan, C.; Farquharson, J. The solace of radicalism: Self-uncertainty and group identification in the face of threat. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 46, 1061–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, D.; Briñol, P.; Petty, R.E.; Gandarillas, B.; Mateos, R. Trait aggressiveness predicting aggressive behavior: The moderating role of meta-cognitive certainty. Aggress. Behav. 2019, 45, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A. Uncertainty–identity theory. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 39, 69–126. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly, A.H. Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Social-Role Interpretation; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, J.T.; Helmreich, R.L.; Stapp, J. The Personal Attributes Questionnaire: A Measure of Sex Role Stereotypes and Masculinity-Femininity; University of Texas: Austin, TX, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Hogg, M.A.; Adelman, J. Uncertainty–identity theory: Extreme groups, radical behavior, and authoritarian leadership. J. Soc. Issues 2013, 69, 436–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, L.; Hogg, M.A. Going to extremes for one’s group: The role of prototypicality and group acceptance. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 46, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bos, K. Making sense of life: The existential self trying to deal with personal uncertainty. Psychol. Inq. 2009, 20, 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedikides, C.; Strube, M.J. Self evaluation: To thine own self be good, to thine own self be sure, to thine own self be true, and to thine own self be better. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1997; Volume 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H. Self-schemata and processing information about the self. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1977, 35, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.D.; Trapnell, P.D.; Heine, S.J.; Katz, I.M.; Lavallee, L.F.; Lehman, D.R. Self-concept clarity: Measurement, personality correlates, and cultural boundaries. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.D.; Assanand, S.; Paula, A.D. The structure of the self-concept and its relation to psychological adjustment. J. Personal. 2003, 71, 115–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scala, J.W.; Levy, K.N.; Johnson, B.N.; Kivity, Y.; Ellison, W.D.; Pincus, A.L.; Wilson, S.J.; Newman, M.G. The role of negative affect and self-concept clarity in predicting self-injurious urges in borderline personality disorder using ecological momentary assessment. J. Personal. Disord. 2018, 32, 36–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGregor, I.; Marigold, D.C. Defensive zeal and the uncertain self: What makes you so sure? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 85, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGregor, I.; Zanna, M.P.; Holmes, J.G.; Spencer, S.J. Compensatory conviction in the face of personal uncertainty: Going to extremes and being oneself. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 80, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozenkrants, B.; Wheeler, S.C.; Shiv, B. Self-expression cues in product rating distributions: When people prefer polarizing products. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 44, 759–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M.B. The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1991, 17, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickett, C.L.; Silver, M.D.; Brewer, M.B. The impact of assimilation and differentiation needs on perceived group importance and judgments of ingroup size. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 28, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.U.; Hogg, M.A. Self-uncertainty and group identification: A meta-analysis. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2020, 23, 483–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, D.L.; Sherman, S.J. Perceiving persons and groups. Psychol. Rev. 1996, 103, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A.; Sherman, D.K.; Dierselhuis, J.; Maitner, A.T.; Moffitt, G. Uncertainty, entitativity, and group identification. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 43, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskalenko, S.; McCauley, C. Measuring political mobilization: The distinction between activism and radicalism. Terror. Political Violence 2009, 21, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trip, S.; Bora, C.H.; Marian, M.; Halmajan, A.; Drugas, M.I. Psychological mechanisms involved in radicalization and extremism. A rational emotive behavioral conceptualization. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doosje, B.; Loseman, A.; Van Den Bos, K. Determinants of radicalization of islamic youth in the Netherlands: Personal uncertainty, perceived injustice, and perceived group threat. J. Soc. Issues 2013, 69, 586–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakan, D. The Duality of Human Existence: Isolation and Communion in Western Man; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1966; Volume 395. [Google Scholar]

- Abele, A.E.; Wojciszke, B. Agency and communion from the perspective of self versus others. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 93, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coolsen, M.K.; Nelson, L.J. Desiring and avoiding close romantic attachment in response to mortality salience. Omega-J. Death Dying 2002, 44, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebauer, J.E.; Paulhus, D.L.; Neberich, W. Big two personality and religiosity across cultures: Communals as religious conformists and agentics as religious contrarians. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2013, 4, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, W.K.; Bonacci, A.M.; Shelton, J.; Exline, J.J.; Bushman, B.J. Psychological entitlement: Interpersonal consequences and validation of a self-report measure. J. Personal. Assess. 2004, 83, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morf, C.C.; Horvath, S.; Torchetti, L. Narcissistic self-enhancement: Tales of (successful?) self-portrayal. In Handbook of Self-Enhancement and Self-Protection; Alicke, M.D., Sedikides, C., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 399–424. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, M.T.; Critelli, J.W.; Ee, J.S. Narcissistic illusions in self-evaluations of intelligence and attractiveness. J. Personal. 1994, 62, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Inman, J.J.; Mittal, V. gender jeopardy in financial risk taking. J. Mark. Res. 2008, 45, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt, D.; Inman, J.J.; Argo, J.J. The influence of friends on consumer spending: The role of agency-communion orientation and self-monitoring. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 48, 741–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterich, K.P.; Mittal, V.; Ross, W.T., Jr. Donation behavior toward in-groups and out-groups: The role of gender and moral identity. J. Consum. Res. 2009, 36, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.F.; Louis, W.R. When will collective action be effective? Violent and non-violent protests differentially influence perceptions of legitimacy and efficacy among sympathizers. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 40, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, S.C.; Taylor, D.M.; Moghaddam, F.M. Responding to membership in a disadvantaged group: From acceptance to collective protest. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 58, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).