1. Introduction

A major reason for the research interest in governance practices is the increase in demand for greater managerial accountability and responsibility after a number of accounting scandals [

1]. Most of this research has focused on the features of the board of directors, because it plays a key role in the development internal control systems [

2] and accountability levels [

3]. Research has shown the positive effect of good governance practices on transparency, financial performance, financial reporting and holding managers accountable (see e.g., [

4,

5]).

Initiatives for developing guidelines and better practices in public sector governance have been in the agenda of most Western countries for more than 25 years, for improving stakeholder engagement and demonstrating that public entities have reliable administrative structures that enable them to be efficient and effective. In 1995, the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy [

6] concluded that the Cadbury Report on governance in corporations was also relevant to public sector organizations and urged them to adopt it. Core governance aspects include accountability, transparency, integrity stewardship, leadership and efficiency [

7]. These aspects are classified into two groups: conformance and performance [

8,

9]. Conformance deals with monitoring and supervising executive performance and maintaining accountability. Performance deals with strategy and policy-making.

The most frequent approach in the academic literature to the study of the relationship between conformance and performance is to focus on one aspect of these two broad governance dimensions. Including an approach which includes these two dimensions in the analysis of governance mechanisms and its effects provides insights to their functioning in the public sector setting. The focus of our study is on the Spanish central governmental agencies. Our objective is to observe the relationships between governance dimensions in a comprehensive model, which allows us to better understand how they develop in the public sector. In this paper, we use Structural Equation Modeling, the Partial Least Squares approach (PLS-SEM), to study governance more comprehensively in Spanish central government agencies. In particular, the conformance characteristic of governance is studied considering the amount of online disclosures and the quality of the financial statements reported, as key elements of accountability. Accountability, a key conformance dimension, is closely linked in the public sector to the asymmetry of information between ministers, managers and stakeholders, which, in the public sector, has been shown to be more complex than in the private sector, open-ended or not explicitly defined and, thus, not easily monitored [

10]. Accountability in the public sector, a multidimensional concept that includes, among other aspects, the quality and reliability of disclosures, is improved by reducing information asymmetry [

11,

12]. The performance characteristic of governance is studied considering the characteristics of the governing body, organizational features, and financial performance. PLS-SEM allows researchers to study complex relationships between variables, including several dependent and independent variables.

The paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 is devoted to presenting the theoretical framework of our study. In

Section 3 hypotheses are drawn.

Section 4 briefly describes the context of the Spanish central government agencies.

Section 5 explains the research design and the methodology used.

Section 6 presents our results, which are discussed in

Section 7. Finally, conclusions are drawn in

Section 8.

2. A Multi-Theoretical Framework for Sustainability in the Public Sector

Agency theory suggests that the disclosure of information is a means of enhancing accountability by reducing the information asymmetry between principals and agents, managers being accountable to principals. The accountability relationship is characterized by the focus of the principal on controlling the agent, because agents have more information than principals, which can be exploited for self-gain [

13,

14]. Citizens are considered the principal, and the public entities’ managers act as their agent to protect the public interest [

15,

16]. However, according to Calabro et al. [

17] and Shawtari et al. [

18], there are multiple players in public entities, including citizens, private investors and governing entities. Thus, in the public sector, governing bodies and managers, rather than being accountable to principals, are publicly accountable to, and under the scrutiny of, citizens and stakeholders. However, given that managers are mostly politically linked, and they are likely to serve their own political interests and/or the political interest of the Minister who appointed them, the principal’s interest is not maximized in a situation where the agent is motivated by self-interest rather than public interest [

18,

19]. Since the separation between citizen and manager is very high, the possibility of opportunistic behavior is strong [

17]. The ability of the principal to curb opportunistic behavior depends on how much information it has about the performance of the agent and the quality of the information available. In this complex situation, governance features are required to perform multiple functions: to safeguard public interest, to guarantee protection to stakeholders, and to ensure the quality of the information disclosed and compliance with the law [

20].

Even though agency theory has traditionally been considered the basis for the design of governance structures, critics point out that agency theory does not completely explain various outcomes and behaviors in governance settings [

21]. Thus, other theories are also being gradually applied to support, complement, or even substitute the agency theory in explaining the transparency and quality of information in the public sector. In particular, the stewardship theory has been used to complement the agency theory when discussing governance practice in public sector agencies [

13,

14,

22]. Stewardship theory is seen as a particular case of the agency theory [

22], in which the principal (owners) and the agents (managers) have similar objectives, so cooperation and collaboration is emphasized [

23]. The stewardship theory proposes that the agents are motivated to act in the best interests of their principals and make decisions that are in the best interests of the overall organization in cases where different stakeholders express competing objectives [

24]. Therefore, the main difference between principal–agent and principal–steward relationships is the degree of goal congruence [

25]. Whereas the principal-agent relationship is characterized by low goal congruence and proneness to low trust, the principal–steward is characterized by high goal congruence and a propensity toward high trust. Stewardship theory also stresses that the concern of managers for their reputation and their intended career progression compel them to act in the interest of principals [

26]. However, this theory stresses that there is some degree of pro-social motivation in any steward, which may or may not be tapped by principals, and does not necessarily imply that agents will be exclusively motivated by pro-social goals [

14].

In terms of accountability, a “principal–steward” relationship may result in lower control and accountability levels from agents to principals than in a “principal–agent” relationship. When principals delegate tasks to stewards who put organizational goals above self-interest, problems related to bureaucratic drift remain minimal [

25]. Thus, the type of relationship will most likely affect disclosure and accountability levels of the agencies. Increased transparency and quality of financial information is the way governing bodies and managers show public accountability and consistency with the goals and objectives of the entity, with positive consequences for the image and the reputation of the entity [

27,

28]. This may be an important way to improve the trust of citizens, other tiers of the public administrations, businesses, civil associations and other stakeholders in the public entity [

29,

30,

31,

32]. Transparency and the disclosure of reliable information to outside parties is a key aspect for public sector agencies. Under an agency theory approach, transparency and information are useful in controlling managers and making them accountable for their decisions, as well as for the overall performance of the organization. Under a stewardship theory approach, public sector agencies may gain support from the community by showing, i.e disclosing, the fulfillment of the economic and social goals of the organization, which ensures the survival of the entity, while serving as an intrinsic reward for its managers. The recent work of Torfing and Bentzen [

33] supports the stewardship model approach in the management of public sector organizations because of its positive effects on employees, users and organizations, although some elements of the agency model approach are necessary for the achievement of these effects.

Before concluding this section, it is important to highlight that, in the public sector, in addition to the problem of defining the type of relationship which exists between the agents-stewards and principals, there is the problem of identifying one participant in the relationship. Whereas the identification of the agent or steward, i.e., the governing body and/or the managers, is easy, the identification of the principal is more problematic. For government agencies, on the one hand, the minister and key officials of the parent ministry can be seen as principals of the agency. On the other hand, government agencies are part the public sector and act in the interest of the citizenry, meaning that citizens are the real principals of the government agencies. In terms of accountability, Luke [

34] distinguishes between “upward” and “downward” accountability. “Upward accountability” does not imply that the accountability process will be visible to outside parties and tends to involve predetermined actors/parties, potentially excluding larger constituencies, whereas downward accountability is often defined as the answerability of government to the public on its performance [

35]. Analyses of the quality of financial reporting and online disclosures can also help to identify the principals and the type of relationship between them and the governing bodies, or managers, of public sector entities.

4. The context of the Central Government Agencies in SPAIN

Like the UK agencies [

56], Spanish agencies operate at arm’s length from their parent ministries and have considerable autonomy and freedom of action. This freedom is accompanied by obligations to meet annual specific financial and operational targets agreed with the parent Minister. These targets are directed at achieving specific outcomes, financial management and the quality of service delivered. Spanish central government agencies can be allocated into five main categories according to their activities and regulation [

43]. These entities can be administrative, commercial or devoted to healthcare and research activities, with the ability to use their own income in their management, which is not allowed for other public sector entities [

57]. Some of these entities perform key activities in the economic, cultural and social areas. These include, among others: the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation and Development, the Spanish equivalent to the British Financial Conduct Authority (Comisión Nacional del Mercado de Valores), the equivalent to the HM Revenue and Customs in the UK (Agencia Tributaria), the Spanish Air Safety Agency, the Spanish Weather Forecast Agency, the Spanish National Library, the Institute for Cinematography and Visual Arts, the National Statistics Institute, the Nuclear Security Board, the entity that manages the Prado Museum or the several organizations in charge of the management of rivers and underground waters in Spain. Thus, these organizations play a key role in the lives of citizens. Agencies represent more than 27 percent of national civil servants and manage about one third of central government expenditure [

43].

There are variations in the composition of governing bodies of Spanish central government agencies but all of them have a president and a board [

43]. The board has similar responsibilities than boards of directors in the private sector or in other public sector entities. Within the board there is one person acting as a chief executive officer (CEO). CEOs are personally responsible for day-to-day operations, and they are directly accountable to the responsible minister who, in turn, is accountable to Parliament. Members of the boards are appointed by the parent ministry, other ministries, regions, municipalities, the private sector and trade unions. Garcia-Juanatey et al. [

57] argue that the introduction of the public agencies in Spain has improved transparency in the Spanish Public sector, promoting an awareness by civil servants of the importance of rendering accounts of their activities. However, other entities linked to the Spanish public sector do not show good disclosure levels. The results of Royo et al. [

35] show that Spanish SOEs do not consider websites a key tool to communicate with their stakeholders. These authors argue that the online disclosures of these entities are mainly focused on financial issues, and most SOEs are silent about their policies, objectives and corporate governance structures, which suggests that they are accountable to shareholders and not to the public in general.

5. Research Design and Methodology

5.1. Sample and Data

The initial sample consists of the 196 agencies controlled by the Spanish central government. Within the term ‘agencies’ we include executive agencies, administrative agencies, consortiums, business-like agencies and other autonomous entities, listed on the

Inventario de Entes del Sector Público Estatal (

https://www.igae.pap.hacienda.gob.es/sitios/igae/es-ES/BasesDatos/ClnInvespe/Paginas/invespe.aspx) at 31st December 2015. For all these entities, we conducted a data search considering three aspects: the website available, financial statements available and information about their governing body/boards of directors. Of the agencies, 168 had a website. We found complete annual accounts allowing us to conduct analyses about their quality for 107 agencies. Financial data for each agency had been collected from financial statements for the year ending on 31st of December of 2015, published either on the website of the Internal Audit Office, the IGAE or in the Spanish official gazette (BOE). Information about the boards of directors was found for 141 agencies. Once the information about these three aspects is combined, the number of agencies available for the analyses is 77, i.e., almost 40% of the total population. Therefore, the final sample of 77 agencies has been determined by the availability of information for the three aspects explained above. Implications about the disclosure and availability of information from Spanish agencies are presented in the discussion section. The agencies in the final sample obtain, on average, higher scores on online disclosure than the sample of the 168 agencies with websites.

5.2. Structural Equation Model Using PLS-SEM

One of the main problems in the analysis of the transparency and accountability of public sector entities is the difficulty of determining the variables that capture these elusive concepts. Therefore, the choice of a statistical tool that fits the characteristics of these entities and their outputs and outcomes is crucial. In this setting, we considered the Structural Equation Model Partial Least Square (PLS-SEM) approach (SmartPLS 2.0 software) to be the appropriate technique for the analysis. Three main advantages of this technique can be highlighted. First, it uses constructs as variables. Constructs, also called latent variables, are made up of several items or indicators to better capture the characteristics of the complex ‘reality’ being studied, strengthening the results and their interpretation. Second, it allows the inclusion of more than one ‘dependent variable’, so the influence of one variable (construct) on two or more dependent variables can be measured at the same time. It also allows the study of interactions between variables; that is, some variables can be both a dependent variable and an independent variable. So, the structural model allows researchers to study complex relationships between variables with different effects. Third, while other approaches to SEM, such as covariance-based methods, have strong sample-size requirements, PLS-SEM restrictions are generally smaller. A sample of 77 cases, like ours, can be considered adequate considering the total number of entities in the population (196).

5.3. Dependent Variables

With PLS-SEM, all dependent variables are constructs, so they better capture the quality of the financial statements and the transparency of the Spanish central government agencies.

5.3.1. Financial Quality Score

Numerous studies use measures of discretionary accruals as surrogates for earning quality [

58,

59,

60,

61]. The flexibility afforded through accrual accounting makes the accrual component of earnings less reliable than the cash flow component and is, therefore, a potentially useful measure for examining the quality of financial reports. Discretionary Accruals (DA) are accounting accruals that differ from accruals that are expected according to the entity’s activity. As earnings management can involve either income-increasing or income-decreasing accruals, we use the absolute value of discretionary accruals as a proxy for earnings quality [

62].

In order to better capture the quality of the financial statements, we created a construct,

Fin_(un)quality, with the absolute value of DA estimated cross-sectionally from three models frequently used in the literature: abDA1 (Kasznik), abDA2 (Jones) and abDA3 (modified Jones) (see

Appendix A). The variables are scaled by lagged assets to mitigate the effect of heteroscedasticity. This way, the construct shows deviations from the real result, regardless of the sign of the DA. We estimated these equations for the 107 entities with available financial data. (We used all agencies with available financial data to estimate these models regardless of whether they have or do not have data on corporate governance in order to obtain more robust estimations of DA. The modified Jones model requires information not available for three entities, which reduced the entities for which estimations were conducted with this model to 104. We also conduct a correlation analysis to observe the relationship between the budgetary result and the estimated discretionary accruals, to better explain and interpret the relationship. For this analysis, discretionary accruals are included with their sign.

5.3.2. Transparency Indexes

To assess the transparency of the Spanish agencies, we carried out a content analysis of their websites, based on the Spanish legal framework for freedom of information, between July 2016 and February 2017. This is an adequate period in terms of the analysis of the relationship between financial quality and transparency for the annual financial statements of 2015. In the Spanish public sector, the preparation of the financial statements takes longer than in the private sector and the financial statements approved by the management team are usually available during the last quarter of the following year. In this way, congruency between the analysis of the financial statements and transparency is ensured.

In our analysis of the websites, we gave each item the value ‘1’ if it appears in the website and ‘0’ if not. This methodology has been applied by most academic papers for gauging the informational contents of the websites. We depart from the checklist developed by Pina and Torres [

43]. From that list, we used for our analyses 76 items and allocated them into six categories. The categories in our study are slightly different than the ones used by these authors. First, the financial dimension used by these authors is divided into two categories in order to better capture the type of information the entities disclosed about their performance. Second, during the stage of assessing the measurement model, some items were removed in order to achieve adequate measurement scales (as explained below in the results section). The six categories used for our study are: (1)

Financial information, FI, (six items), focused on financial information and reports and (2)

Performance information, focused on additional non-financial information about performance, PI, (four items), assess the degree of transparency with regard to the use of financial resources, financial position, performance and audit reports.

Citizen dialogue, CD, (twelve items), includes information about interaction and participation tools with citizens.

Institutional information, II, (twenty-five items), describes the degree of transparency with regard to the government’s mission and operations, its institutional activities and other information.

Accessibility, AC, (five items) focuses on the development of tools for making the website contents accessible to disabled people and the public at large. The

Usability category, US, (24 items) refers to the ease with which users can access information and navigate the Web portal as a function of how accessible and user-friendly the specific contents are. The score of each category is the result of adding up the ‘1s’ obtained in the content analysis.

We allocated the six categories into three constructs, each made up of two of the categories, so transparency can be analyzed considering three main dimensions, namely, performance transparency, citizen transparency and transparency easiness. Performance transparency (

TR_perform) is made up of FI and PI and it assesses the transparency of the entities with respect to their financial performance and service quality. Citizen transparency (

TR_citizen) is made up of CD and II, and it assesses the information provided to the citizenry about the institution and the communication channels with users and citizens. Transparency easiness (

TR_easiness) is made up of AC and US and it assesses the quality of the websites and the features that enable users to navigate easily. Serrano-Cinca et al. [

63] use a similar methodological approach, PLS-SEM and website content analysis, to create constructs to determine the factors that explain the financial transparency of banks on the Internet. As explained, we included a correlation analysis to observe the relationship between the budgetary result and the estimated discretionary accruals, to better explain it and interpret it.

5.4. Independent Variables

We include all the independent variables of the model, presented in this section, as single indicators. The use of single-item indicators (or constructs) is not restricted in PLS-SEM [

64]. This approach allows us to identify better the governance, financial and organizational factors that are related to financial quality and transparency. Our model has six independent variables, representing three features that can affect the quality of the financial reporting and online disclosure levels, namely the governing body, financial results and organizational characteristics. There are two independent variables for each of these three features.

5.4.1. Governing Body Variables

We included in our model two features of the governing body to study how it is related to both financial quality and transparency, namely

BDcontrol and

BDsize.

BDcontrol is a variable that captures the percentage of ‘non-independent’ board members over the total number of members. Non-independent directors are those appointed by the parent ministry and/or by other central government ministries. Non-independent directors represent the central government control on the agency. We consider independent directors to be those who come from other tiers of the public administration, such as regional and local governments, and directors who do come from trade unions, NGOs, civil associations and industries. Therefore, independent directors represent different stakeholder interests and may seek to influence the organization’s response to their demands [

65]. Independent directors promote global relationships and board independence because people with different backgrounds provide new insights and perspectives [

66], increase discussion, promote the exchange of ideas [

67] and improve organizational value [

68]. Thus, in fact,

BDcontrol represents the opposite of board independence.

BDsize captures the number of board members. This board characteristic is frequently included in the study of the influence of the boards on the performance and transparency of economic entities. The number of directors could condition the activities of monitoring and control of the accountability process of the entity, even though the empirical results are not conclusive.

5.4.2. Financial Variables

Two variables, namely RSbudget and Surplus, aim to capture the information of the net borrowing/net lending figure used by Eurostat to monitor the fulfillment of the deficit limits established for the Eurozone countries. Net borrowing/net lending is a concept included in the European System of Accounts under the accrual basis of accounting. As the national budgets of Eurozone countries apply the modified accrual or cash basis of accounting, Eurostat makes a number of adjustments to the non-financial items of the budgets of different countries. Therefore, the budgetary result represents the basis on which Eurostat makes the adjustments to the national budgets. Even though the surplus is elaborated on an accrual basis, it is not equal to the net borrowing/net lending variable because not all items included in the surplus are included in the net borrowing/net lending variable (for instance, amortizations, depreciations and financial items are not included) and tax revenues are accounted for under the cash basis and not the accrual basis. Therefore, the budgetary result and the surplus represent the range of values captured by the net borrowing/net lending figure. Net borrowing/net lending cannot directly be included in the model because countries disclose the information for the whole central government and not for each agency under its control (agencies manage around 30% of the central government budget). In our analysis, we included two variables that capture the financial performance of the Spanish agencies. The first is RSbudget, which captures the absolute value of the budgetary result of the agencies. For the entities that do not elaborate a budgetary statement, we used as a proxy the absolute value of the financial result in its natural log form. The second variable that captures the financial performance of the agencies is a dummy variable, Surplus, which takes ‘1’ when there is a financial surplus at the end of the financial year, and ‘0’ otherwise.

5.4.3. Organizational Variables

We selected two organizational variables to study their relationship with financial quality and transparency: the size of the organization (Size) and the accounting system used, that is, whether it uses private or public sector accounting standards (IFRS). Size captures the amount of resources used by the entity to provide goods and/or services. We measure it as the total assets reported in the balance sheet and it is introduced into the model in its natural log form. IFRS is a dummy variable that takes value ‘1’ when the entity elaborates its financial statements according to private sector GAAP, mainly based on the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS), and ‘0’ when it applies public sector accounting standards, mainly based on the International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS). This variable reflects the accounting framework of the entity and captures differences in managerial flexibility.

5.5. Model

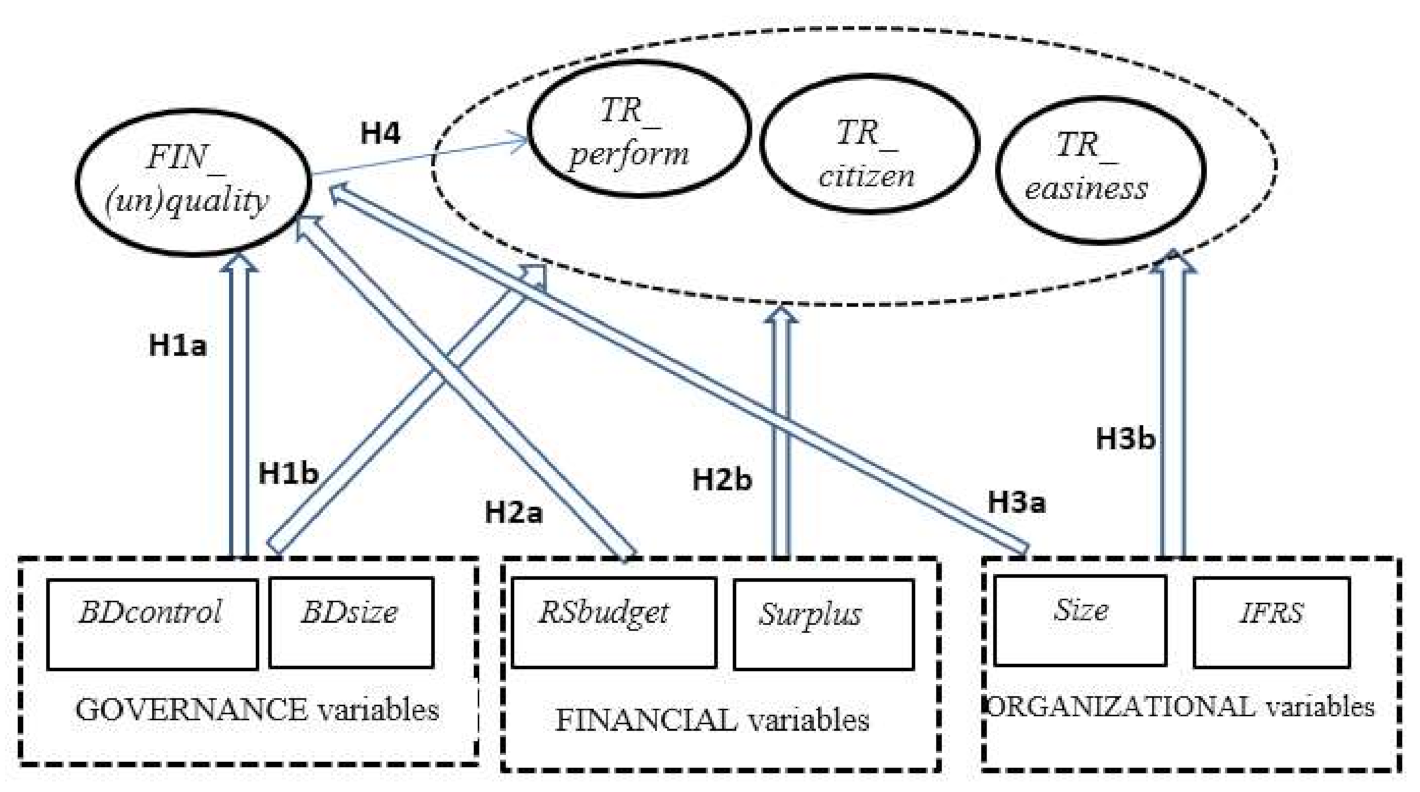

Figure 1 is a graphic representation of the variables and constructs in the model and the relationships, and hypotheses, to be tested. Ellipses represent constructs made up of several items. Rectangles represent constructs with only one variable. Our model tests the relationship between the governance, financial and organizational variables and both financial quality and transparency, as well as the relationship between financial quality and transparency in the performance dimension. First, the dependent variables, those that capture the financial quality and the transparency of the entities studied, are constructs because they are elusive concepts and our design allows a better representation. Second, we included the independent variables as single-item variables because they are specific aspects of the entities and allow an easier and better interpretation. For each feature of the entities analyzed (governance, financial and organizational aspects) we included two variables so the model does not give more importance to one dimension than to the others. Third, the model also studies the relationship between financial quality and financial transparency, because accountability is not only about transparency, but also about reporting useful and reliable information.

Financial quality and the budgetary result are included in their absolute values, so it is not possible to observe the relationship of their signs. As explained, we included a correlation analysis to observe the relationship between the budgetary result and the estimated discretionary accruals (DA). We allocated entities into two groups. One is made up of entities with a financial surplus for the year and the other consists of the rest of the entities, that is, those that present a deficit or zero in their financial surplus/deficit for the year. Then, we carried out a Spearman correlation analysis between the absolute value of the budgetary result, in the natural form, and the three estimated discretionary accruals maintaining the sign of the estimation (DA). The correlation between these aspects allowed us to observe the effect of the DA on the financial performance, that is, whether DA are used to ‘move’ the financial result towards break-even or not. It is worth recalling that, for those entities that do not report budgetary information, the financial result included is the one reported in their income statement.

6. Results

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the variables included in the analyses. The mean of the different estimations of the discretionary accruals range from 0.040 and 0.044, which are lower than those reported in previous literature. For example, in the private sector, some results are: 0.077 [

58], 0.08 [

59] and 0.066 [

69]. In British local governments, Arcas and Martí [

36] find 0.081. Spanish agencies show, on average, low scores in transparency. For the financial and non-financial information, the percentage of items present on the website is, on average, 46.5%. In terms of information for citizens, scores are higher, with an average presence of 47.4% of the items for citizen dialogue and 69.2% of the items for institutional information. The ease of use of the websites presents good scores for accessibility, an average of 62.4%, while, on average, scores are low for usability.

Boards (BDsize) are quite large, with an average size of almost 19 members and a presence of 53% non-independent directors (BDcontrol), which means that they are a majority on the board which allows them to control the entities. The budgetary result (RSbudget) of the entities included in the sample is, on average, more than €44million, and 48 of them present a positive financial result for the year (Surplus). The entities analyzed manage, on average, assets of almost (Size) €740 million, and 25 of them apply GAAP following private sector accounting standards (IFRS).

PLS-SEM analysis must be developed in two stages: the measurement model analysis and the structural model analysis. The measurement model assessment involves the examination of the adequacy of the measurement scales. The structural model focuses on testing the causal paths between the constructs that compose the theoretical model. As the sample is made up of the agencies with complete data, there are no missing values. This explains the analyses carried out for the two stages and the results obtained.

6.1. Analysis of the Measurement Model

We estimated the measurement model with PLS-SEM in order to analyze its internal consistency. This process essentially involves three stages [

70]. The results of the estimation of our measurement model are presented in

Table 2. First, the unidimensionality of the indicators is evaluated using their factor loadings (λ). This permits an evaluation of whether or not each indicator of the construct is highly correlated with the characteristic that it intends to capture. All λ exceed the threshold of 0.7. Second, reliability is explored using the CRI value to measure composite reliability and Cronbach’s Alpha for simple reliability. Reliability indicates whether or not the set of variables are consistent in what they intend to measure. The CRI values exceed the critical threshold of 0.7–0.8 [

71] for all variables. For the Cronbach’s Alpha, 0.7 is usually considered the critical threshold. This threshold is exceeded for

FIN_(un)quality and

TR_citizen, is close to that threshold for

TR_perform (0.67) and is 0.57 for

TR_easiness. Academic papers such as Malloy and Agarwall [

72] present CRI values around 0.6, so all our values are acceptable. Hair et al. [

64], using the work of Bagozzi and Yi [

73] as their reference, indicate that the assessment of the internal reliability should be based on the CRI value and the use of Cronbach’s Alpha should be avoided. In any case, the validity of the values must take into account the meaning of the items and whether they are capturing similar aspects. Third, validity is assessed by using convergent validity and discriminant validity. Convergent validity is analyzed through the average variance extracted (AVE) values and evaluates the degree to which the indicators represent the construct.

Table 2 shows that all the AVE values are above 0.5, which guarantees convergent validity [

73]. Discriminant validity indicates whether each construct in the model is significantly different from the others. The most accepted method for PLS-SEM is the comparison of the square root of the AVE values and the correlation between variables.

Table 3 presents the square root of each construct’s AVE values on the diagonal and the estimated correlations for each pair of constructs off the diagonal. Single-item variables, that is, our independent variables, take the value ‘1’ for all the measures: Cross-loadings, Alpha, CRI and AVE. Therefore, this information is not presented in

Table 2.

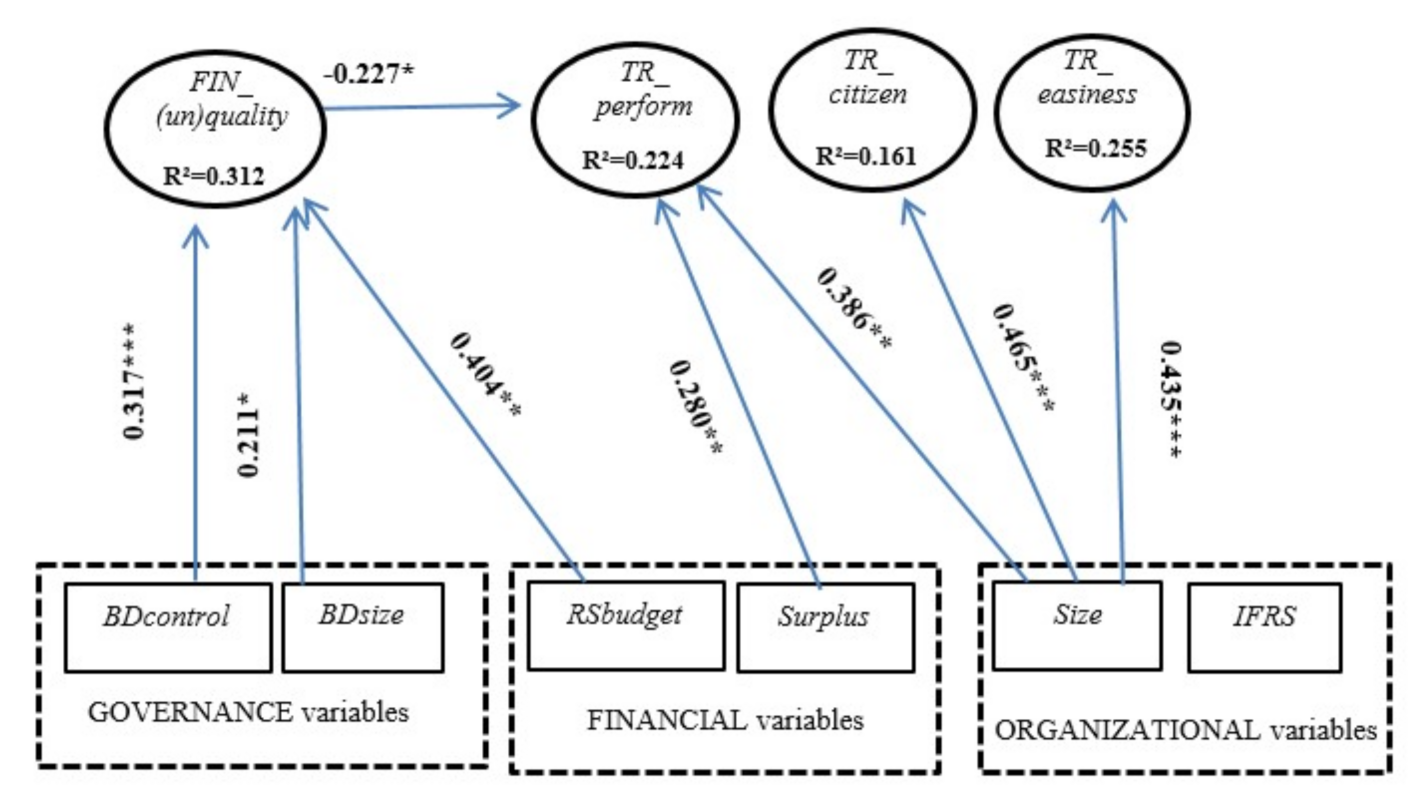

6.2. Analysis of the Structural Model

Having confirmed the adequacy of the measurement scales for the constructs included in the model, the structural model is estimated. To assess the significance of the path coefficients, we use a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 subsamples. The results of the structural model that tests the relationships presented in

Figure 1 are shown in

Figure 2 and in

Table 4.

The structural model is examined by observing the R2 values of the dependent variables. The model explains 31% of the variance in the construct reflecting the (un)quality of the financial statements, 22% of performance transparency, 17% of transparency and communication with the citizenry and 26% of ease of use. PLS-SEM does not provide a global indicator of the goodness of fit of the whole model. The two governance factors of our model, BDcontrol, at the 1% level, and BDsize, at the 10% level, are significantly and positively related to a worse financial quality (FIN_(un)quality), and their relationship with the three transparency (TR_perform, TR_citizen and TR_easiness) dimensions is not significant. That is, the larger the board and the higher the presence of non-independent directors, which reflects a higher level of control from the parent Ministry, the greater the discretionary accruals estimated in their financial statements. Therefore, for those entities that do not follow good governance practices, the quality of the financial information is worse; that is, H1a is supported. H1b is not supported because there is no significant relationship between board characteristics and transparency. As discussed below, this might be due to a lower concern with downward accountability (to citizens and the public) than with upward accountability (to authorities and the government).

For the financial variables, the budgetary result is positive and significantly related to

FIN_(un)quality. That is, a larger budgetary result is related to a worse financial quality, so H2a is supported. Having a surplus for the year results in a higher transparency of organizational performance (

TR_perform). The financial variables do not show a significant relationship with the other two transparency dimensions,

TR_citizen and

TR_easiness. Therefore, H2b is partially supported. As explained in

Section 5.3, because discretionary accruals and budgetary results are included in their absolute values, a correlation analysis has been carried out distinguishing between entities that report a financial surplus for the year and those that do not. This analysis allows us to observe the ‘intention’ of managers when using discretionary accruals. For these analyses, discretionary accruals are presented in their natural value. Results are presented in

Table 5.

The results of

Table 5 suggest that, for entities that report surpluses, there is a negative correlation between discretionary accruals and the budgetary result. The correlation is not significant but suggests an interesting relationship. Entities with a higher budgetary result seem to use discretionary accruals to reduce their financial results in order to show a figure closer to the break-even and, in this way, compensate a high budgetary result. For entities with a deficit, the correlation is similar, but the interpretation is that the effect pretends to get closer to break-even by showing a better result by reducing this deficit.

For the organizational factors studied, the size of the entity is negatively related to the level of financial (un)quality, that is, the larger the entity the better the quality of the financial statements, but this relationship is not statistically significant. The type of accounting regime, which, as explained, also captures different administrative processes, is not significantly related either to the quality of the financial statements or to the transparency of the entities analyzed (H3a not supported). However, the size of the entity is significantly related to the three transparency dimensions studied (TR_perform, TR_citizen and TR_easiness), so hypothesis H3b is supported.

Finally, our results indicate that the quality of the financial statements and the disclosure of financial and non-financial information, captured by the construct TR_perform, are related dimensions. Financial accountability is not only about presenting a greater quantity or a better quality of information, but of presenting both characteristics together. The significant and negative relationship between the level of discretionary accruals and TR_perform indicates that those who ‘manipulate’ more their financial statements disclose less information. This result supports our hypothesis H4, that is, accountability is a multidimensional concept and that its dimensions are interrelated.

7. Discussion

The sustainability of some public sector entities is in the agenda of many governments. Sustainability from a broad perspective, that is, considering the economic, environmental and social dimensions as well as legitimacy to perform activities that pursue to achieve developments in those dimensions. Thus, one element for entities to survive is to achieve those goals while following good governance practices, which require performing and conforming with those practices. In particular, the accountability of the governing bodies of public sector entities must be real throughout the disclosure of more and better, more reliable, information.

Academic research has identified the size and the independence of the governing body as two key features influencing accountability and information disclosure. Thus, they have been included in empirical models designed to test the influence of the board of directors on the accountability and performance of public and private entities. Our results indicate that the prevalence of non-independent directors and, to a lesser extent, larger boards, are related to higher discretionary accruals; that is, they have a negative effect on the quality of financial information. This shows the benefits of having independent directors on the governing body to monitor the quality of the financial reports and, thus, to hold managers accountable. Although the size of the governing body increases diversity, because large boards can more easily include the participation of different stakeholders, larger boards have some inconveniences such as the costs of poorer communication and decision-making associated with larger groups, as well as a greater likelihood of control of the board by the CEO. Agency and stewardship theories highlight the importance of independent directors as representatives of stakeholders, thus indirectly, the size of the board, because it makes it easier to introduce them in boards. However, our results support a negative relationship between larger boards and the quality of the financial statements. This shows that size does not guarantee either greater stakeholder representation or a higher percentage of independent directors. The quality of financial information is significantly related to the political and background variety provided by the percentage of independent directors. Independent directors in public entities are representative of other public administrations governed, sometimes by different political parties and public and private sector stakeholders related to the activities and/or goals of the agency. For CIPFA [

6] one of the major considerations of the Cadbury Committee was to examine the issue of the balance of power within entities. Independent members not involved in the management of the entity bring other perspectives to strategy development and decision-making and hold the executive accountable for its performance [

74]. Therefore, the quality of the financial reports is enhanced by the members not appointed by the central government.

The pressure of Eurozone requirements has been introduced into the model through the budgetary and financial results of the agencies. Agencies might be motivated to manage net operating cost numbers for several reasons [

10]. One is to signal that they meet their objectives and provide services at a reasonable cost. Another is that they need to justify funding from Parliament. Budgetary results are calculated on a modified cash basis of accounting and financial results on a full accrual basis. Both results establish the ends of the range through which the net borrowing/net lending required by the European System of Accounts (ESA) moves. Public managers focus especially on budget figures and, at the end of the period, they use the adjustments of budgetary figures required by the ESA to calculate the deficit and the net borrowing/net lending on an accrual basis to smooth their financial results. The sign of the correlation analysis provides indication that entities with a positive result use discretionary accruals to reduce their reported financial results in order to show a figure closer to the break-even established for Spain by the Eurostat for the fulfilment of the limits of deficit and debt and, in this way, compensate a high budgetary result. For entities with a deficit, the correlation is similar but the interpretation is that the effect is to get closer to break-even by showing a better financial result by reducing this deficit. These results are similar to those found by Pina et al. [

10] for UK executive agencies which show that managers adjusted reported financial results in order to keep the net operating cost of agencies around zero. The budgetary result is the data used by Eurostat to estimate the net borrowing/net lending of agencies in order to assess the fulfilment of the deficit and debt limits established for each Eurozone country. The financial result represents the financial performance measured under the accrual basis which is a figure closer to the net borrowing/net lending of the European System of Accounts than the budgetary result. Under this system, good budgetary results are not necessarily seen as reflecting good managerial performance. Our analysis suggests that, with good budgetary results, discretionary accruals are used to smooth financial results in order to bring them closer to the Eurozone deficit and debt limits.

Our analysis does not find a significant relationship between the governance features of agencies and their transparency. This may be because agencies are free to design their websites and select the information disclosed, and all transparency indices are mostly based on the information published on the Internet. Our analysis confirms that the financial performance is related to the transparency levels of the Spanish agencies. In particular, entities with a positive financial result (surplus) for the year have a significantly higher level of transparency in the performance dimension than those that have a deficit. However, having a surplus for the year does not affect the other transparency dimensions. Similarly, a better budgetary result does not affect transparency levels. This result is consistent with the idea that those who achieve a positive financial result are more willing to disclose information about the performance of the entity, but not necessarily about other aspects, supporting the agency theory argument of possible opportunistic behavior by managers.

Our results indicate that organizational features influence transparency levels with a significant relationship between the size of the entity and the three dimensions of transparency based on Spanish freedom of information legislation. The size of the entities affects their visibility, large entities being under a narrower scrutiny from stakeholders than small ones. These results are hypothesized by agency and stewardship theories, which support the idea that large entities are exposed to closer monitoring by institutions and stakeholders and, therefore, they are more interested in gaining legitimacy. However, our results are valid for the agencies of our sample. For a significant number of entities it has not been possible to obtain the information needed for our analyses. It seems, in line with the results of Royo et al. [

35] that some public sector entities do not feel real urgency to report to the citizenry. Agencies most likely perceive their parent ministry and the organizations represented on their governing body as their principals. The composition of the governing body does not seem to be the factor that affects online disclosure.

Our analyses provide support to the idea that accountability is a concept with interrelated dimensions. In particular, the quality of the financial statements and the amount of information provided about the performance of the entity are positively related. Those who elaborate ‘better’ financial statements are ‘more willing’ to disclose information about the results and performance of the entity. These results are consistent with the world-wide tendency to expand the content of financial reports with non-financial information. The European Commission has recently published guidelines for big companies to report non-financial information based on the international integrated reporting framework in order to improve their accountability and transparency. Public accountability implies making the accountability process transparent to outside parties. Agency theory sees increased transparency as the way that managers show public accountability and consistency with the goals and objectives of the entity, with positive consequences for the image and institutional reputation of the entity among stakeholders. Under the stewardship theory, increased transparency can be seen as an indicator of public accountability and commitment with the users of the service. This may be an important way of improving the trust of citizens, taxpayers, other tiers of the public administrations, businesses, civil associations and other stakeholders in the public entity. This greater trust will most likely result in the sustainability of the services provided by the organization because the citizenry is more aware of their importance. However, our results suggest that Spanish central government agencies need to improve their accountability towards citizens. In particular, they have to make important efforts to improve their transparency, online disclosure, levels. They should disclose information to the citizenry through their websites, which is now a common information tool used by citizens. The information disclosed should include performance information as well as information about those who manage the entity. As enforcement of transparency-related legislation is scarce in Spain, legal, compulsory measures should ensure disclosure requirements on the Internet.

Finally, we must acknowledge some limitations of this study. One limitation of this work is that it focuses on Spanish central government agencies and the results may vary if the study is applied to public sector entities with a different degree of autonomy or controlled by regional governments, or in different countries. Second, our analyses are focused on one year and only on those entities for which complete data was available. The growing introduction and use of Web 2.0 and social media tools provide arguments for new studies to observe their influence on the accountability of public sector entities. Future research should also focus on other European agencies in order to compare results.

8. Conclusions

The sustainability of some public sector entities is a key concern for many developed governments. The public sector is under the scrutiny of the citizens who demand better service quality, value for money and greater accountability. The agency and stewardship theories are useful for explaining the complex and open-ended relationships between governors, managers and citizens/stakeholders in the autonomous entities of the public sector. This study is focused on the accountability dimension of the public sector in terms of the quantity and quality of online disclosures. The composition of the boards of directors is revealed in this study as key in explaining the level of quality of the financial reports of the agencies studied. A lower presence of independent directors, who usually represent a variety of stakeholders not appointed by the central government, is an explanatory factor of a lower quality of the financial reports. Independent directors are typically representatives of other tiers of the public administration, which may be governed by different political parties, NGOs or business organizations related to the activities and/or goals of the agency. Therefore, independent directors will be more likely to enhance the reliability of financial reports used to hold these entities accountable.

Our findings show that the quality of the financial information is also affected by the pressure that the requirements (deficit limits) of Eurostat put on public entities, which leads to the use of smoothing practices. These practices are limited by the independent board members not involved in the direct management of the public entity, who are interested in public accountability aspects.

Our analysis has found a significant relationship between transparency and the size of the agency. The size of the agencies affects their visibility and public accountability, large entities being under narrower stakeholder scrutiny than small ones. Public accountability implies making the accountability process transparent to outside parties. Agency and stewardship theories support the idea that large entities are subject to closer monitoring by institutions and stakeholders so they are more interested in gaining legitimacy. The results also indicate that public accountability is concerned with both the quality of the financial statements and the disclosure of financial and non-financial information. These results are consistent with the world-wide tendency to expand the content of financial reports, introducing non-financial information through Integrated Reporting. Adequate financial and non-financial disclosures are needed for the sustainability of entities across sectors.