1. Introduction

Most countries strive to empower society’s members by incorporating them into constructive participation in their society. Empowerment is an integrated philosophy that aims to stimulate society’s members to effectively contribute to the process of identifying their needs and working to meet them positively and maintaining the factors of sustainability [

1]. The importance of university education and scientific research has been dominated by globalization, global competition, innovation and technological advancement in the twenty-first century. To ensure sustainable competitive advantage for universities, emphasis on faculty members participating in the academic and research process has become an essential component. Consequently, as part of the roles and duties of universities, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) attaches considerable significance to scientific research to meet the requirements and expectations of growth and sustainability based on a knowledge economy. In this rapidly evolving globalized environment, Bontis (1996) asserts that human capital could be the only sustainable competitive advantage owned by the organization. In this context, KSA supports specialized research institutions and centers and conducts seminars and scientific conferences in these universities, thus increasing the empowerment of faculty members [

2].

Women represent half of society, and therefore women’s empowerment has become one of the priorities on the agenda of world countries since the beginning of the twenty-first century. Decision makers and civil society organizations have been invested in engaging the role of women in the comprehensive development programs in the last few decades [

3]. The inclusion of women in the production process requires the provision of appropriate conditions and the treatment of the various difficulties that hinder the activation of the role of women in the development process [

4]. Global Goal No. 5 is one of the 17 global goals adopted by UNESCO to achieve sustainable development, and it mainly targets gender equality. UNESCO is trying to contribute to initiating a rich environment for gender equality by coordinating various actions in the world [

5]. Therefore, several governmental and non-governmental institutions have adopted women’s empowerment concepts in their strategic goals, where empowerment is linked to development elements based on competitiveness, sustainability and social justice. Thus, one of the indices counted by the advancement of nations is women’s engagement in development [

6]. Moreover, on 22 December 2015, an annual International Day was adopted by the General Assembly honoring the vital role women and girls play in science and technology [

7].

In the Arab countries, women are among the most marginalized energies in the development process, despite the urgent need to include them in development plans and processes and to integrate them in their projects that aim to improve the quality of life and establish a better environment. To do so, women’s freedom has become one of the Arab world’s strategic goals for the advancement of human development and the liberalization of women’s capabilities [

8]. Many Arab countries have taken a significant progress in empowering women in scientific research, for instance Tunisia, Algeria, Egypt, Kuwait and Sudan, where women constitute more than 40% of the total researchers in these countries. In contrast, the representation of women in scientific research in Libya, Morocco, Jordan, Palestine, Iraq, Qatar, Oman and Bahrain are still not satisfactory, which varies from 21.4% to 39% [

9].

In KSA, the Saudi government has been keen on supporting the role of Saudi women, despite the challenges that lie in the social legacies, to achieve much success in empowering them in several fields. For instance, women in KSA have achieved substantial gains by taking over political and leadership positions in a number of institutions and government ministries, in addition to their distinguished presence in the Saudi congress council [

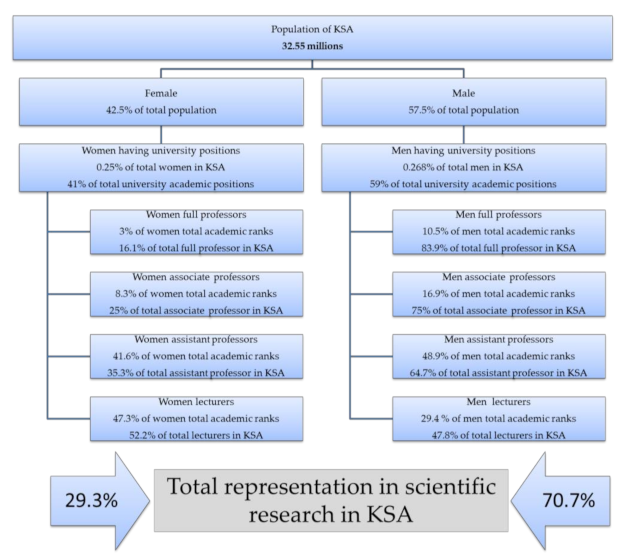

10]. Moreover, although higher education for girls began only in the year 1970, at present, the enrollment of girls is almost equal to the boys. Annual statistics indicate an increase in the contribution of Saudi women in all fields, as they represent nearly half of the number of faculty members in Saudi universities. In 2000, the number of female faculty members was 6442 out of the total number in Saudi universities (18,325) with a percentage of 32%. In 2017, the number reached 34,247 out of the total number (83,884), with a percentage of 41% (

Figure 1). When we reviewed the statistics of the Saudi Ministry of Education, we noticed that there was adequate representation of women in higher education institutions, which is very close to the proportions of men (41% versus 59% of the total academic jobs in the Saudi universities, respectively. Additionally, 0.25% of all women versus 0.268% of all men in Saudi Arabia) [

11]. Remarkably, there is no noticeable gender discrimination in Saudi universities in term of employment. As university academic positions require a university higher degree, which is a result of the synergistic roles of women and universities, it is likely that both of them perform their proper role in this respect. It is worth noting that the academic ranks of men are logically developed and follow the normal distribution (10.5% full professor, 16.9% associate professor, 48.9% assistant professor and 29.4% lecturer). On the contrary, the career growth of women tends to be weak (3% full professor, 8.3% associate professor, 41.6% assistant professor and 47.3% lecturer). Since career growth is primarily linked to activity and productivity in scientific research, it is clear that there are deficiencies in women’s activities in scientific research. This braves the above and implies that, unless there are other factors that play a vital role, the role of universities and women in women’s academic career development is ineffective. In fact, we support both possibilities. In addition to the role of women and universities, the donors also play a vital role in supporting research activities, which reflects positively on women’s engagement and empowerment in scientific research.

Recently, the Saudi Vision 2030, which is in alignment with UNESCO’s sustainable development plan and goals, aims to develop women’s talents, invest in the unlimited capabilities of women and provide them with the opportunity to enhance their future and the ability to contribute to the development of Saudi society and economy, bearing in mind that women represent 50% of university graduates in Saudi Arabia [

12]. Reaping the rewards of implementing the initiatives of the Saudi Vision 2030 has also begun in this regard. In this context, the Women’s Report on Business and Law 2020 issued by the World Bank Group demonstrated the leap that had taken place in terms of Saudi women’s empowerment, and in the monitoring of progress in legislation and regulations in which KSA was the highest reforming country in the world with an increase in 45 points compared to the benchmark last year [

13]. The Saudi Vision 2030 also targets innovation and creating a stimulating environment to stimulate entrepreneurship and creativity, with the aim of enhancing its influence and competitiveness in the dynamic global scene. This is also in line with UNESCO’s 9th Sustainable Development Goal [

5].

Remarkably, despite the female faculty forming 41% of the total in Saudi universities, women researchers represent only 23.2% of the total researchers in KSA, which is still less than the global average (29.3%, see

Figure 1) [

9,

11]. Therefore, the empowerment of women in scientific research and the enhancement of the ingredients for innovation in KSA in line with the Saudi Vision 2030 and UNESCO goals in this regard remains modest, which leads to modest pivoting of women and their pioneering role in scientific research and developmental paths, as well as reflection on the evaluation and advancement of society’s plans.

The research problem in this study lies in the lack of an instrument assessing the role of key factors affecting women’s empowerment in scientific research and figuring out the correlation between these different factors. Thus, the importance of this study is to uncover the most important obstacles facing women researchers (those holding a master’s degree or higher and working in research institutes) in KSA. The study aimed to assess the role of three different factors, which include (1) the role of universities, (2) the role of the donor (including local community organizations, funding agencies and charities) and (3) the role of women researchers in women’s empowerment in scientific research. Additionally, it aimed to explore the correlation/interplay between these factors.

For the present study, the following two hypotheses were intended to be tested by the researchers:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). The role of the university will positively influence the role of donor institutions in women’s empowerment.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). The role of researchers will positively influence the role of the university in women’s empowerment.

2. Materials and Methods

In this study, the researchers investigated the current status of women’s empowerment at KSA universities and research institutes. The study followed the quantitative method research using a self-administered questionnaire. The survey was built to follow the steps listed for building a questionnaire on educational research [

14]. An online, bilingual (Arabic/English) survey was used for data collection. The online survey had four sections.

Section 1 comprised the study information. In

Section 2, the demographic data were collected that included (1) age, (2) nationality, (3) marital status, (4) scientific field, (5) medium of instruction of the last qualification and (6) academic rank. Initially, 25 items were distributed among 3 different subscales:

Section 3,

Section 4 and

Section 5.

Section 3 included the 14 items measuring the role of the university.

Section 4 comprised 4 items measuring the role of donor institutions, while

Section 5 measured the role of women researchers through 7 items. Items of these 3 sections were developed by researchers according to the outcomes of focus groups and presentations presented in the women’s empowerment workshop in the educational research symposium at Umm al-Qura University on 11 March 2019. To avoid tendency toward the middle, items in each of these subscales were rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree) that assessed the levels of participants’ perception and experiences towards the designed items. A panel of 5 experts evaluated the content validity of the subscales. The panel was composed of (1) two associate professors specialized in educational studies, (2) two associate professors who work in scientific research development and (3) one statistician assistant professor. According to their evaluation, one item from the last subscale was excluded, leaving 6 items for the last scale.

A non-random convenience sampling method was employed to select the participants by completing the anonymous online survey questionnaire. The online cross-sectional survey was conducted between 22 July and 17 November 2020. To recruit the participants from 43 different state and private universities and research institutes in KSA, we circulated the online survey link through various online communication channels, including email and social media platforms (WhatsApp, Twitter and LinkedIn) The link included an invitation to participate voluntarily in the study, the informed consent which identified study details and purpose was presented before the questionnaire was started. No personal information of the participants was requested by the survey. Participants had a choice to complete either the English or Arabic version of the questionnaire.

Cronbach’s alpha was used to measure the reliability of the risk factor scale according to Manning and Munro [

15]. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 was used to analyze the data. Descriptive statistics were conducted to analyze and describe different variables (demographics and perceptions). Pearson’s correlation coefficient, regression analysis and one-way ANOVA were used to determine women’s empowerment based on the role of the university, the role of donor institutions and the role of researchers. Significant relationships confirmed by ANOVA were further investigated using Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test as post hoc analysis.

4. Discussion

Despite the progressed achievement in several domains, women researchers are still under-represented in scientific research activities in most countries and their research contributions are still limited [

18]. In this study, we strived to figure out the most important obstacles facing women researchers in KSA, to assess the role of each factor in women’s empowerment and the correlation/interplay between the different factors. This study was conducted during the early period of implementing the national transformation programs adapted from the Saudi Vision 2030 which emphasizes and is committed to women’s empowerment in all life aspects. Therefore, this study identifies the challenges and obstacles facing women’s empowerment in scientific research in KSA.

Our study assessed the role of universities, donor institutions and researchers in enabling female researchers in scientific research. The results showed that the role of universities (Mean = 2.4378, ±SD = 2.4953) and the role of donor institutions (Mean = 2.3859, ±SD: 2.2786) have not yet reached the satisfactory level according to the respondents’ perceptions. To a greater extent, our study showed that the role of female researchers in empowering themselves in scientific research was moderately satisfactory (Mean = 2.6757, ±SD = 2.5094). The overall mean score of the women’s empowerment scale was moderate (Mean = 2.49). Undoubtedly, these results explain why women are underrepresented in scientific research activities in Saudi Arabia. These results are consistent with previous studies that highlighted the weaknesses in women’s empowerment programs by government institutions and donor institutions in empowering women [

19]. Universities have an important role in developing a knowledge-based society by contributing to knowledge production, transmission, diffusion and use. University scientific research, through its impact on the development of knowledge and human resources, including female researchers, is one of the basic pillars of social and economic development. The growth in innovation capacity is one of the determinants of universities’ social and economic role. The participants attributed this result to the weak interest of university administrations in the fair distribution of the work of faculty members and the primacy of administrative and academic work over research work. Lund (2014) attributed the issues facing Swedish women who wish to be an ideal academic and a distinguished researcher to the heavy teaching load, administrative work and young children [

20]. However, according to the perception of the women researchers in our study, the family role of women and being a mother with young children does not affect scientific research activities here. This can be explained by the fact that in addition to the rules in KSA, most family duties in KSA and other Arab Gulf states that have a high level of financial income rely on housemaids and babysitters, thus having a positive impact on the dynamism and opportunities of women’s labor [

21]. In addition to the university’s failure to support and facilitate language editing in writing research, insufficient access to conferences and the balance between academic, administrative and research duties was also reported. This is in agreement with a Swedish study which reported that collaboration and building research networking with researchers from prestige universities as well as publishing research work in English (to be publishable and citable) is certainly necessary for academic career building [

20].

Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicated that that English as the medium of instruction during the last qualification was able to significantly improve the role of researchers compared to the Arabic language. These findings are consistent with our and other previous studies conducted in KSA and other Arab countries which reported language obstacles, less access to scientific conferences and increased academic and administrative duties of the faculty members as obstacles against researchers’ empowerment [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. On contrary, from the participants’ point of view, the university supports the empowerment of women researchers by setting research priorities and training courses, providing the infrastructure for conducting research, and gender equality in supporting research activities, supporting mixed research groups, breaking barriers of gender mixing and taking into account the family and social role of women. In the light of these results, some of the obstacles that women researchers are facing in the subscale of the university’s role seem to be general obstacles faced by both genders and are not limited to female researchers only. However, since the universities in KSA are divided into two campuses, male and female, and given the proportion of female faculty members (41% of the total faculty members), there is no doubt that this requires more academic and administrative work by women. Therefore, these obstacles have more negative effect on women researchers than their male counterparts.

Numerous local and international studies have confirmed the role of donor institutions in supporting scientific research and empowering researchers and have shown the modest support of these institutions for women [

25,

26,

27]. Despite the availability of huge numbers of research chairs supported by donor institutions in the KSA universities (more than 189 research chairs in 2013), our study clearly showed that there are weaknesses in the role of donors in empowering women in scientific research. Of the four elements that were evaluated in this subscale, our study highlighted three elements as obstacles facing researchers (with a mean ranging from 2.1749 to 2.3308). The obstacles were summarized by the insufficient financial support of donor institutions for research work, attendance at conferences and the spreading of the culture of voluntary research work. These results are consistent with the Adesua-Lincoln study, which showed that many women lack information and counseling procedures for their project funding sources [

28]. This very serious limitation affects their empowerment. In addition, these results can be interpreted according to the traditional view of the role of charitable work in the care of donor institutions rather than to support research, which is based on sponsoring and providing aid and assistance to needy groups in society. Moreover, although the majority (more than 75%) of donor institutions support specialized research chairs in basic, applied and medical sciences, the Tukey post hoc test showed that the average scores in religious sciences (Mean = 11.25, ±SD = 3.75) and social sciences (Mean = 10.07, ±SD = 2.45) were significantly different from basic and applied sciences (Mean = 8.92, ±SD = 2.27) and medical sciences (Mean = 8.80, ±SD = 2.49), in favor of religious sciences and social sciences researchers. This means that scholars of religious sciences and social sciences were significantly more satisfied with the role of donor institutions. This can be explained by the fact that most of the researchers specialized in the fields of basic sciences, applied sciences and medical sciences are residents or graduates of western countries who have spent long periods outside the country, which may negatively affected their knowledge in Saudi donor institutions, their goals and how to reach them. This supports the need to address the fourth factor in this subscale by increasing the dissemination of the culture of volunteer research and its sources in universities.

Women should rely on their own dignity, confidence, motivation and optimism to achieve their empowerment [

21]. From the respondents’ point of view, they were highly satisfied with their endeavor to empower themselves in scientific research (Mean = 2.6757, ±SD = 2.5094). However, the results indicated that there are some obstacles, as the researchers saw a weakness in their necessary expertise in research management and enrollment in training programs that empower their research capabilities. Therefore, researchers should seek to enroll in training programs specific to their research interests to empower themselves. In this regard, the experience of nurses in Cleveland demonstrated how nurses were empowered and increased their research productivity in quantity and quality through enrollment in training programs in scientific research [

29].

Pearson’s correlation and linear regression analysis among the three subscales revealed that the role of university enhances the role of the donor institutions in women’s empowerment in scientific research and implied that 35.7% of the variation in the role of donor institutions can be explained by the model containing the role of the university (β = 0.598,

r2 = 0.357,

p < 0.001). This implies that there is a strong correlation between both roles in empowering women in scientific research in KSA. However, universities should pay more attention in strengthen the role of donors in women’s empowerment in research through aligning their goals with donors’ goals and expectations, and vice-versa. In the knowledge economy, universities should promote interactive ties with other enterprises and external networks in addition to their partners [

30,

31], and this is in order to take benefit of mutual advantages and complementary strengths. In KSA, a study conducted by the “Center for Research and Studies at the Chamber of Commerce and Industry” reported that 72% of enterprises in KSA do not benefit at all from the research and development capabilities available in Saudi universities. The study points out that 41% of these enterprises do not know about the facilities and the cooperation possibilities available at universities. This reflects the weakness of communication channels between universities and the private sector. [

32,

33] explain the weakness of cooperation in research and development by the following main reasons: (i) the lack of competitive research outputs in universities due to limited governmental support; (ii) in many cases, universities wait for private sector initiatives to request partnership and do not take the initiative; (iii) universities lack centers of transfer for converting the results of scientific research into preliminary products that can be marketed before commercial production; (iv) the interest of many of the faculty members in universities to achieve academic promotion rather than to invest the results of their scientific research. Therefore, Saudi universities should overcome these obstacles and further enhance the role of donor institutions in women’s empowerment in scientific research.

On the other hand, Pearson’s correlation and linear regression analysis also revealed that the role of researchers has a significant positive influence on the role of the university, with (β = 0.310, r2 = 0.096, p < 0.001), implying that only 9.6% of the variables in the role of the university can be explained by the model containing the role of researchers. Thus, despite the positive impact of the role of researchers on the role of universities in empowering women researchers, this correlation required to be strengthened. In contrast, no significant direct correlation was obtained between the role of the researchers and the role of donors. Thus, more attention should be paid to establishing a direct correlation between both roles.

Collectively, the status of the complementary roles demonstrated that the role of the university mediates the role of researchers and the role of donors, while there is almost no direct interplay between the role of donors and the role of researchers. According to our results, the status of the complementary roles of the universities, women researchers and donors in KSA and their interactions between each other are described in

Figure 2.

In conclusion, there is still a paucity of studies focusing on the role of factors affecting women’s empowerment in scientific research in KSA. In this study, we identified the weaknesses in the factors affecting women’s empowerment in scientific research and how the synergistic contributions of these factors are necessary to enhance women’s role in scientific research as a pivotal key player in sustainable community development. Women researchers achieved great progress in empowering themselves as scientific researchers. This will enhance their sense of self-efficacy in community development. However, they still have not received the required support from the universities and donors. Thus, decision makers need to implement proper corrective actions to strengthen women’s empowerment in scientific research in KSA. These actions should be prioritized as part of the Saudi Vision 2030 and synchronize with the progress of other countries regarding this issue as a response to the UNESCO goals.

5. Conclusions

This study presented an instrument for assessing the role of key factors affecting women’s empowerment in scientific research in KSA. The most important obstacles facing women researchers in KSA are related to the huge administrative and academic duties, the regulations specifying the organization of the researchers’ work, language barriers, conference attendance, donor funding, women’s experience in research management and research training programs. English as the medium of instruction of the last qualification and the scientific fields have positive impacts on the role of researchers and the role of donors, respectively. In general, the interplay between the different roles varies from weak to strong and implies that more corrective actions should be implemented to strengthen these correlations and subsequently empower women researchers in sustainable development in scientific research.

The study has spatial and temporal limitations. It targeted women researchers in KSA only. Thus, the results consider the perceptions of women researchers working in KSA and do not necessarily represent the perceptions of women researchers working elsewhere, having different experiences in this domain. The study was conducted during the COVID-19 Pandemic, which might affect the perception of women researchers during the lockdown period, and this, could be the reason for the limited representation of participants. The study can also be extended to male researchers to assess the role of different factors and identify women-specific obstacles from general obstacles that might face both sexes. Therefore, the study can be conducted again at the regional or international level after the pandemic and considering both sexes. The results of the study are according to women researchers, therefore they could be biased towards them. The perception of universities and donor institutions could balance the result of this study.

Despite these limitations of the current study, the findings provide useful insights on the role of the different factors affecting women’s empowerment in scientific research in KSA. Nonetheless, our study is the first research (in KSA, and to our knowledge, worldwide) that considered the role of these factors and analyzed their synergistic effect on women’s empowerment.