Sustainable Aging and Leisure Behaviors: Do Leisure Activities Matter in Aging Well?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Aging Population and Sustainability

- (Goal 1. No poverty) preventing older people from falling into poverty;

- (Goal 2. Zero hunger) achieving food security and improved nutrition;

- (Goal 3. Good health and well-being) ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being for all at all ages;

- (Goal 4. Quality education) providing inclusive and quality education for all and promoting lifelong learning;

- (Goal 5. Gender equality) achieving gender equality and empowering all women and girls;

- (Goal 9. Industry, innovation, and infrastructure) building resilient infrastructure, promoting inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and fostering innovation;

- (Goal 10. Reduced inequality) Reducing inequality within and among countries;

- (Goal 11. Sustainable cities and communities) making cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable;

- (Goal 16. Peace, justice, and strong institutions) promoting just, peaceful, and inclusive societies for sustainable development, providing access to justice for all, and building effective, accountable institutions at all levels.

2.2. Aging and Leisure: South Korea’s Case

2.3. South Korea as an Aged Society and Older Adults’ Leisure

3. Methods

3.1. Design and Participants

3.2. Ethics and Reflexivity

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Findings and Analysis

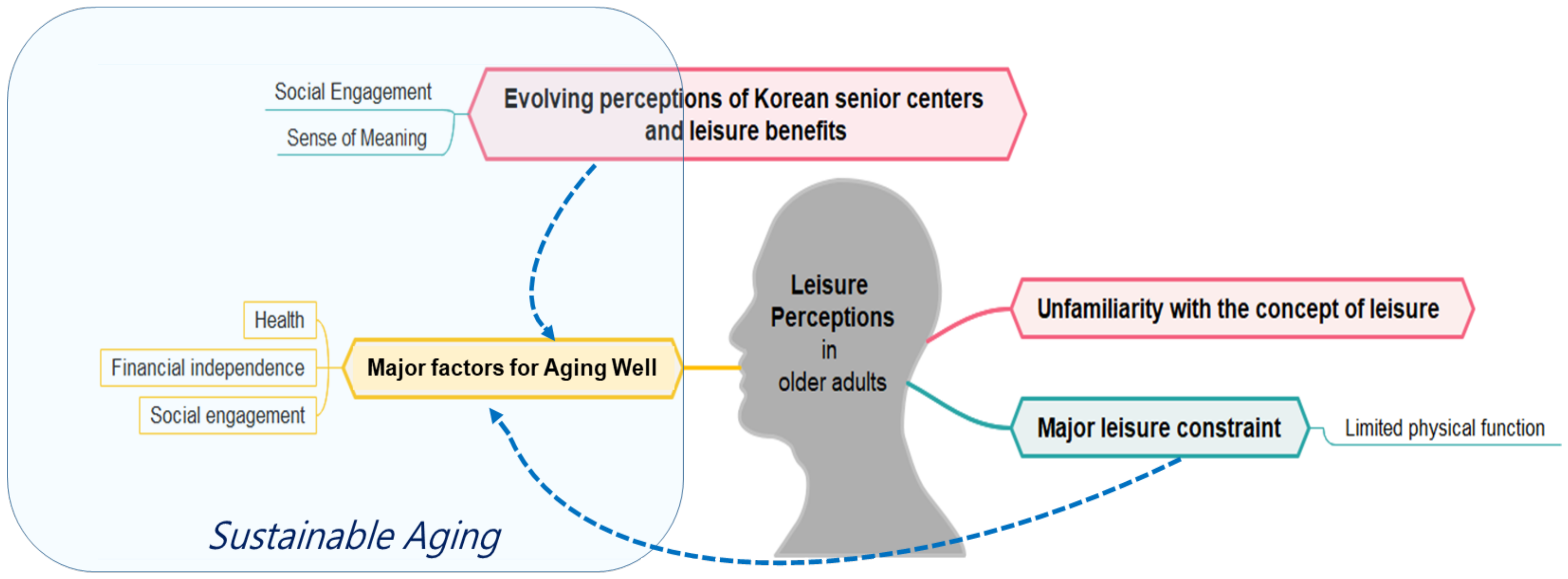

4.1. Unfamiliarity with the Concept of Leisure and Leisure Engagement

“I’ve never heard the terms leisure and leisure activity.… Honestly, I have no idea which activity is good for me and my later life both to maintain health and spend a day pleasantly. I had spent so much time watching T.V. before I decided to come to this center.”

“When I was young, I was really busy every day. In the morning, I had to prepare for my husband going to work and for my children going to school.… But, now it is different. My kids have moved out and my role at home disappeared. Even worse, I have nowhere special to go and nothing special to do. There is nowhere welcoming older people and I feel really lonely.… I am sad because I am treated like a useless old person.”

4.2. Evolving Perceptions of Senior Centers and Leisure Benefits

“At first, truthfully, for some reason I was embarrassed to come to this place. I thought I would look poor so I did not like going.… On parents’ day, my daughter-in-law suggested I go to the senior center to eat lunch and I got angry—am I a beggar who cannot find food? I thought the senior center was a place where people who had nothing to do, had no money, and were not respected by their children went to spend time.”

4.2.1. Social Engagement

“In fact, some people really irritate me. However, I just tolerate them because I just want to enjoy my time more interestingly.… Above all, I am really happy because I am a member of my peer group and I feel a sense of belonging through involvement in leisure programs and meetings.… Therefore, I used to come to the meeting days in spite of poor physical conditions. When I meet my friends, I strongly realize they really welcome me.”

4.2.2. Sense of Meaning

“I’m learning a Korean traditional instrument, Janggu (which is an hourglass-shaped drum). I finally know how to play “Arirang” and other traditional songs. At first I made the mistake of feeling embarrassed about it. Not now. My playing has improved a lot and I’m so satisfied and proud of myself. Yes! I gain self-confidence from this activity. I’m not a useless old person anymore. I am useful and feel greatly appreciated because of that.”

4.3. Limited Physical Function as a Major Leisure Constraint

“I know exercise is good for my health because it’s always on television. But it’s not easy.… When it gets cold, I don’t want to go outside and when it rains, I’m not comfortable. Especially those days, my bones hurt. My physical condition is not good.… I feel exercising is burdensome.”

4.4. Major Factors for Aging Well (LOHAS)

“Health is the most important thing of all. What good are money and success when I lose my health? When I lose my health, I cannot do anything. So, keeping my health should be my top priority and thus, I have always participated in group exercise with my friends at this center.”

“I’m a happier man than other friends because I’m not beholden to my children. I really believe older adults should have economic ability enough to live on by ourselves, as we get older... In fact, money helps the relationship between parents and their children in later life get along better and fewer fights take place. Most friends who have no economic ability feel slighted from their sons/daughters and sons-/daughters-in-law. However, if older parents have financial power, children never abuse or neglect their parents. Anyway, money is very important—to eat everything I want to eat and to enjoy fun activities in later life.”

“To be happy, older adults should have positive thinking. But if we stay at home all day without any social activities and contacts, we never form such positive ideas. So, I really recommend social engagement, especially joining various activities, clubs, or programs at senior centers, to other friends who are staying at home in front of a television.”

5. Discussion and Conclusions

“My son and daughter-in-law gave me a dinner show ticket as my birthday gift. So, I firstly participated in the concert and had a great dinner. After enjoying the show for the first time in my life, I couldn’t forget the great fun time and memories. So, I sometimes go to a concert and theater to enjoy it again, although I am not very well off and have to save pocket money from my son and daughter. Unfortunately, I am just beginning to enjoy such an activity in my seventies. I realize leisure activities give me great energy and induce positive thinking. I believe it’s never too late to have a very nice day. 70s is not an old age.… I am also learning how to use the Internet at this center. Once I can use the Internet well, I hope I can search my favorite songs and shows via the Internet and involve myself in fan sites (laughing).”

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Tourism Organization (UNWTO); United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals—Journey to 2030. Spain: UNWTO. 2017. Available online: https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/pdf/10.18111/9789284419401 (accessed on 27 December 2020).

- Grazuleviciute-Vileniske, I.; Seduikyte, L.; Teixeira-Gomes, A.; Mendes, A.; Borodinecs, A.; Buzinskaite, D. Aging, Living Environment, and Sustainability: What Should be Taken into Account? Sustainability 2020, 12, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, S.; Mutisya, E.; Nagao, M. Population Aging: An Emerging Research Agenda for Sustainable Development. Soc. Sci. 2015, 4, 940–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, S.A. A ‘New Materialist’ Lens on Aging Well: Special Things in Later Life. J. Aging Stud. 2006, 20, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, S.L.; Alzheimer, M. Leisure and Ageing Well. World Leis. J. 2008, 50, 91–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J.P.; Sadana, R. “Healthy aging” Concepts and Measures. J. Am. Med Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruchno, R.; Carr, D. Successful Aging 2.0: Resilience and Beyond. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2017, 72, 201–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rantanen, T.; Portegijs, E.; Kokko, K.; Rantakokko, M.; Törmäkangas, T.; Saajanaho, M. Developing an Assessment Method of Active Aging: University of Jyvaskyla Active Aging Scale. J. Aging Health 2019, 31, 1002–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, A.J.; Claunch, K.D.; Verdeja, M.A.; Dungan, M.T.; Anderson, S.; Clayton, C.K.; Goates, M.C.; Thacker, E.L. What Does “Successful Aging” Mean to you?—Systematic Review and Cross-Cultural Comparison of Lay Perspectives of Older Adults in 13 Countries, 2010–2020. J. Cross Cult. Gerontol. 2020, 35, 455–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strawbridge, W.J.; Wallhagen, M.I.; Cohen, R.D. Successful Aging and Well-being: Self-rated Compared with Rowe and Kahn. Gerontologist 2002, 42, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillant, G.E. Aging Well: Surprising Guideposts to a Happier Life from the Landmark Harvard Study of Adult Development; Little Brown: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.J.; Kim, W.G.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, C. Does Knowledge Matter to Seniors’ Usage of Mobile Devices? Focusing on Motivation and Attachment. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1702–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Lee, W.S.; Kim, K.-B.; Moon, J. Effects of Leisure Participation on Life Satisfaction in Older Korean Adults: A Panel Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooyman, N.R.; Kiyak, H.A. Social Gerontology: A Multidisciplinary Perspective, 9th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Healthy Ageing and the Sustainable Development Goals. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/ageing/sdgs/en/ (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Landorf, C.; Brewer, G.; Sheppard, L.A. The Urban Environment and Sustainable Ageing: Critical Issues and Assessment Indicators. Local Environ. 2008, 13, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Kaushik, I. Design for sustainable aging: Improving design communication through building information modeling and game engine integration. Procedia Eng. 2015, 118, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henning, G.; Stenling, A.; Bielak, A.A.; Bjälkebring, P.; Gow, A.J.; Kivi, M.; Muniz-Terrera, G.; Johansson, B.; Lindwall, M. Towards an Active and Happy Retirement? Changes in Leisure Activity and Depressive Symptoms during the Retirement Transition. Aging Ment. Health 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.-Y.; Yu, C.-P.; Wu, C.-D.; Pan, W.-C. The Effect of Leisure Activity Diversity and Exercise Time on the Prevention of Depression in the Middle-Aged and Elderly Residents of Taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, S.A.; Siedlecki, K.L. Leisure Activity Engagement and Positive Affect Partially Mediate the Relationship between Positive Views on Aging and Physical Health. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2017, 72, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Argan, M.; Argan, M.T.; Dursun, M.T. Examining Relationships Among Well-being, Leisure Satisfaction, Life Satisfaction, and Happiness. Int. J. Med. Res. Health Sci. 2018, 7, 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Barengo, N.C.; Antikainen, R.; Borodulin, K.; Harald, K.; Jousilahti, P. Leisure-time Physical Activity Reduces Total and Cardiovascular Mortality and Cardiovascular Disease Incidence in Older Adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragina, I.; Voelcker-Rehage, C. The Exercise Effect on Psychological Well-being in Older Adults—A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. German J. Exerc. Sport Res. 2018, 48, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.; Aartsen, M.; Slagsvold, B.; Deindl, C. Dynamics of Volunteering and Life Satisfaction in Midlife and Old Age: Findings from 12 European Countries. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.E.R.; Cox, N.J.; Tan, Q.Y.; Ibrahim, K.; Roberts, H.C. Volunteer-led Physical Activity Interventions to Improve Health Outcomes for Community-Dwelling Older People: A Systematic Review. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow-Howell, N.; Lee, Y.S.; McCrary, S.; McBride, A. Volunteering as a Pathway to Productive and Social Engagement Among Older Adults. Health Educ. Behav. 2014, 41, 84S–90S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Korean Elderly Life Conditions and Welfare 2017; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Daejeon, Korea, 2018.

- Statistics Korea. Report on South Korea and World Population Prospects 2019; Statistics Korea: Daejeon, Korea, 2019.

- Tongco, M.D.C. Purposive Sampling as a Tool for Informant Selection. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2007, 5, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.; White, G.; Schmierer, C. Tourism Experiences within an Attributional Framework. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 798–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design Choosing among Five Approaches, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Glesne, C. Becoming Qualitative Researchers: An Introduction, 4th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barriball, K.L.; While, A. Collecting Data using a Semi-structured Interview: A Discussion Paper. J. Adv. Nurs. 1994, 19, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dingwall, L.; Mclafferty, E. Do Nurses Promote Urinary Continence in Hospitalized Older People? An Exploratory Study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2006, 15, 1276–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leech, N.L.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Beyond Constant Comparison Qualitative Data Analysis: Using NVivo. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2011, 26, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelle, U.; Laurie, H. Computer Use in Qualitative Research and Issues of Validity. In Computer-Aided Qualitative Data Analysis: Theory, Methods and Practice; Kelle, U., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998; pp. 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh, E. Dealing with Data: Using NVivo in the Qualitative Data Analysis Process. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2002, 3. Available online: http://www.qualitativeresearch.net/fqs-texte/2-02/2-02welsh-e.htm (accessed on 27 December 2020).

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Establishing Trustworthiness. In Qualitative Research; Bryman, A., Burgess, R.G., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff, A.E.; Ellis, G.D. Influence of Agents of Leisure Socialization on Leisure Self-efficacy of University Students. J. Leis. Res. 1992, 24, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canham, S.L.; Fang, M.L.; Battersby, L.; Woolrych, R.; Sixsmith, J.; Ren, T.H.; Sixsmith, A. Contextual Factors for Aging Well: Creating Socially Engaging Spaces through the Use of Deliberative Dialogues. Gerontologist 2018, 58, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterlin, R.A. Happiness, Growth, and Public Policy. Econ. Inq. 2013, 51, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeste, D.V.; Oswald, A.J. Individual and Societal Wisdom: Explaining the Paradox of Human Aging and High Well-being. Psychiatry 2014, 77, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aday, R.H.; Kehoe, G.C.; Farney, L.A. Impact of Senior Center Friendships on Aging Women who Live Alone. J. Women Aging 2006, 18, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, C.; Kim, H. The Effects of Physical Self-efficacy of Elderly People in Attending the Leisure Facilities and Programs on Life Satisfaction. Korean J. Leis. Recreat. Stud. 2013, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler, M.; Estes, C.L. Readings in the Political Economy of Aging; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Antonovsky, A. The salutogenic model as a theory to guide health promotion. Health Promot. Int. 1996, 11, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, B.; Eriksson, M. Salutogenesis. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2005, 59, 440–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Korea Herald. Education Cost: Government Must Take Up Greater Share. The Korea Herald. 2004. Available online: http://khnews.kheraldm.com/view.php?ud=20140914000332&md=20140917005149_BL (accessed on 25 December 2020).

- Kim, J.; Kim, Y. Generational Differences of Social Support and Life Satisfaction. Korean Elder. Res. 2000, 20, 155–168. [Google Scholar]

| Questions | |

|---|---|

| Episodic Interview | Please explain your normal daily schedule and life. |

| Semi-structured Interview | Do you have a favorite leisure activity? How does this activity benefit you as an older person? What do you think about the senior center? Is it good for your LOHAS (Lifestyle of Health and Sustainability)? What do you think is the most important thing to improve in senior centers for older adults? If you do not have any favorite leisure activity, what is the reason? What constraints prevent you from participating in leisure activities? Have you ever heard the phrase “aging well”? Just tell me your idea how you can age well in your sustainable lives. Are you satisfied with your life now? |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yoon, H.; Huber, L.; Kim, C. Sustainable Aging and Leisure Behaviors: Do Leisure Activities Matter in Aging Well? Sustainability 2021, 13, 2348. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042348

Yoon H, Huber L, Kim C. Sustainable Aging and Leisure Behaviors: Do Leisure Activities Matter in Aging Well? Sustainability. 2021; 13(4):2348. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042348

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoon, Hyejin, Lesa Huber, and Chulwon Kim. 2021. "Sustainable Aging and Leisure Behaviors: Do Leisure Activities Matter in Aging Well?" Sustainability 13, no. 4: 2348. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042348

APA StyleYoon, H., Huber, L., & Kim, C. (2021). Sustainable Aging and Leisure Behaviors: Do Leisure Activities Matter in Aging Well? Sustainability, 13(4), 2348. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042348