Linked(In)g Sport Management Education with the Sport Industry: A Preliminary Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

- i

- to present an educational innovation piloted in a sport management course where LinkedIn is introduced as a driver of students’ career development and as a tool to keep up to date and interact with the sport industry.

- ii

- to propose and pre-validate a new instrument to assess the outcomes of using LinkedIn as a tool which could drive career development, and to keep up to date and interact with the sport industry.

2. Theoretical Pedagogical Underpinnings and Literature Review

2.1. Experiential Learning through LinkedIn

2.2. LinkedIn as a Tool for the Development of the Student’s Professional Profile

- RQ1. Do sport management students perceive LinkedIn as a driver of career development?

- RQ2. Do sport management students perceive LinkedIn as a tool to interact with the sports industry and keep up to date with its developments?

3. LinkedIn’s Educational Innovation

3.1. Contextualisation

- Group “#SMont”: specific private group for all the students of the Ontinyent group.

- Group “#SMval”: specific private group for all the students of the group of Valencia.

- Group “Sport Management Lovers”: a joint group where both students from Valencia and Ontinyent gathered.

- The hashtag (#) is a symbol familiar to students and is attractive, which in social media, in addition to attracting attention, serves mainly to label and filter the content in a specific way, making it easier to locate it if desired.

- “SM” has a double meaning as a double acronym. The first meaning refers to “Social Media” and the second to “Sport Management”.

- “val” and “ont” refer to the beginning of the name of the municipality where the two groups of students involved in the educational innovation were studying, that of the Blasco Ibáñez Campus in Valencia and that of the Ontinyent Campus in Ontinyent.

- “Sport Management Lovers” refers to the passion that both teachers and students have for the course content.

3.2. Objectives of the Educational Innovation

- Specific objectives linked to LinkedIn:

- To familiarise students with the LinkedIn professional network, understand its structure, and navigate between its essential features.

- To create a professional profile on LinkedIn, including the selection of a professional profile and cover photo, preparation of the headline and the “about” (summary), as well as completing other sections of the profile such as experience, education, skills, validations and recommendations, among other aspects.

- To set up a professional network of contacts adjusted to the students’ interests and include students and faculty in maintaining a professional relationship after completing the course.

- To learn how to identify the sports industry’s main stakeholders and how to address them.

- To develop the students’ personal brand, giving them tools to discover what orientation they want to give to it.

- To promote the acquisition of digital skills in sport management students.

- To promote employability and entrepreneurship in sport management students, emphasising elements such as creating a CV and finding a job or possible business partners through LinkedIn.

- Specific work topics linked to the subject matter that was developed through activities in each of the private LinkedIn class groups:

- Women and sport.

- Innovations in the field of sports facilities.

- Volunteer management.

- Marketing in sports entities.

- Management of university sport in Spain.

- Sport management role in Spanish Sport Sciences curricula.

- Sponsorship in the world of sport.

- Brand management of professional leagues.

- The role of social media in sport.

- Machines, algorithms and automation in the sports industry.

- Skills, characteristics and abilities of sport managers.

- Entrepreneurship and innovation in sport.

3.3. LinkedIn Management Training Provided to Students

- Theoretical lectures: these took 5 h, with faculty providing face-to-face training, and inviting a LinkedIn expert to give a masterclass.

- PDF material: material created by the faculty describing LinkedIn and its main features was uploaded to each group’s Moodle.

- Video tutorials: two video tutorials were created, one primary and one advanced, both to guide students on how to create a LinkedIn profile and what aspects to develop within the assignment of the educational innovation.

- Private consultations through LinkedIn messages: taking advantage of the student-teacher interaction facilities offered by LinkedIn, throughout the innovation, the faculty answered the different consultations made by the students.

3.4. Assignment

- Work on the student profiles and create a professional network of contacts: the work was done individually following the faculty’s guidelines to develop the innovation objectives set out in block “A”. The students had to develop all aspects of their profile (e.g., profile and cover photo, headline, summary, experience, education, skills), orienting them towards the professional objective desired by each one. Besides this, specific tasks were also added, such as identifying professional groups on LinkedIn, and sports stakeholders’ profiles.

- Work in the course’s private groups: all of the objectives linked to block “B” were developed under this assignment section. For this purpose, the faculty selected and shared audiovisual content (e.g., videos, photos, papers, infographics) through weekly posts, specifically opening a debate with them. Students answered in the related post by interacting with the students or faculty. A total of ten different activities were published in each private group.

3.5. Assessment

4. Methodology

4.1. Scale Development

4.2. Sample and Testing Procedure

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

5.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

5.3. Reliability

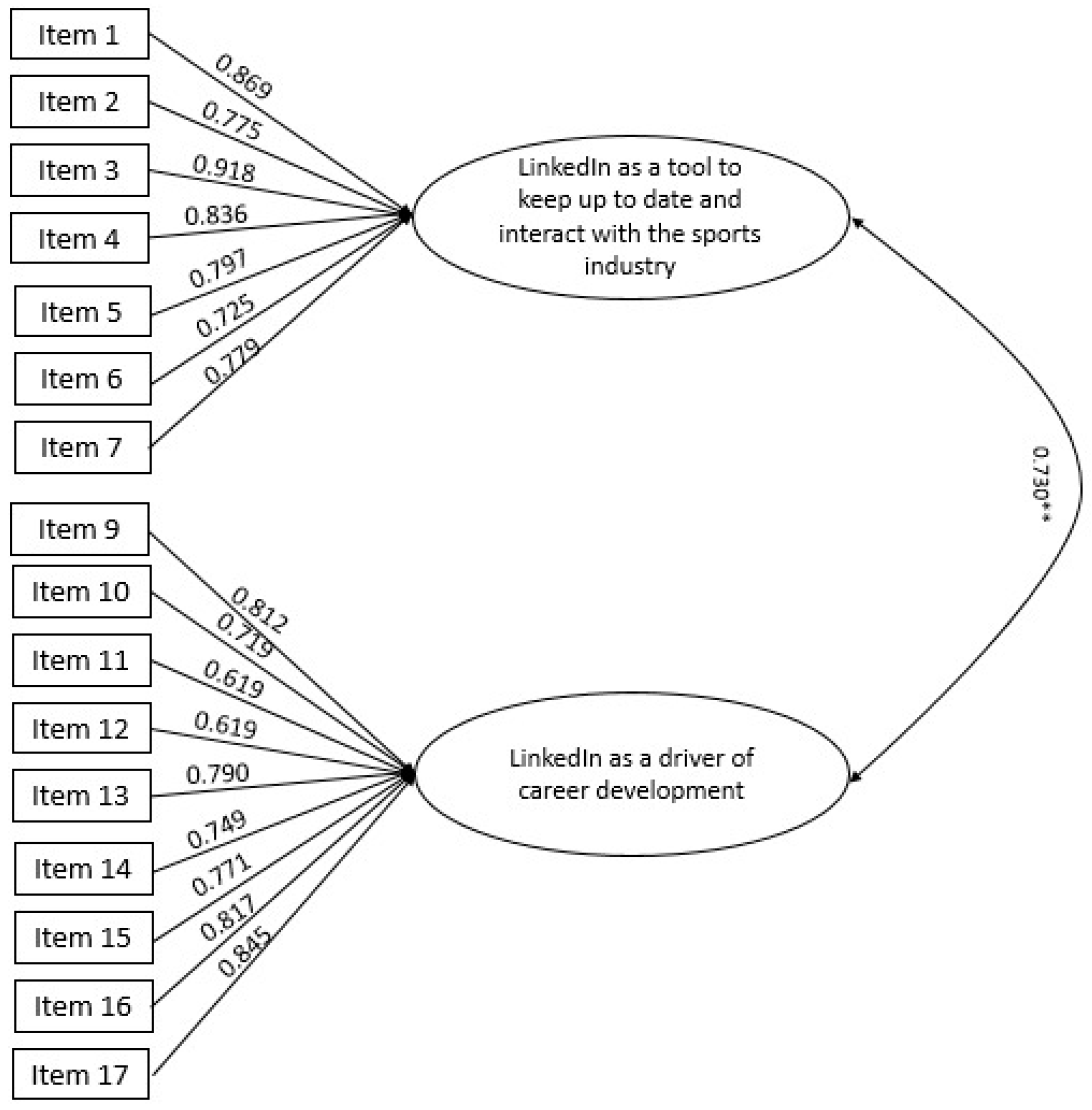

5.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

5.5. Convergent Validity Analysis

5.6. Discriminant Validity Assessment

5.7. Intragroup Comparisons: Post-Test Versus Pre-Test

6. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research Lines

7. Conclusions and Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Item No. | Original LPDP-SMS in Spanish | LPDP-SMS Adapted to English |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | LinkedIn es una buena herramienta para mantenerse informado sobre temas de gestión del deporte | LinkedIn is a good tool to keep informed about sport management issues |

| 2 | LinkedIn puede ayudar a estar al día de los últimos avances en la industria del deporte | LinkedIn can help keep you up to date on the latest developments in the sports industry |

| 3 | LinkedIn me facilitará estar conectado con grupos de interés (stakeholders) de la industria del deporte (clubs, gestores del deporte, entidades deportivas, empresas deportivas, etc.) | LinkedIn will make it easier for me to be connected with stakeholders from the sport industry (clubs, sport managers, sport entities, sport companies, etc.) |

| 4 | LinkedIn te da la oportunidad de seguir y/o estar conectado con gente importante de mi sector profesional | LinkedIn gives you the opportunity to follow and/or be connected with relevant people in my professional sector |

| 5 | LinkedIn puede ser útil para reflexionar de forma crítica sobre temas relacionados con la gestión del deporte | LinkedIn can be useful to reflect critically on issues related to sport management |

| 6 | LinkedIn facilita debatir con profesionales sobre temas de la industria del deporte que me interesan | LinkedIn facilitates discussions with professionals on sports industry topics that interest me |

| 7 | Creo que las empresas pueden valorar positivamente que sepa gestionar LinkedIn | I believe that companies are able to appreciate that I know how to manage LinkedIn |

| 9 | Aprender a usar LinkedIn puede ser una experiencia que me ayudará en mi futuro profesional | Learning to use LinkedIn could be an experience that will help me in my professional future |

| 10 | Creo que aprender a usar LinkedIn va a ser positivo para mi futuro profesional | I believe that learning to use LinkedIn will be positive for my professional future |

| 11 | El valor añadido de LinkedIn depende de cómo lo gestione personalmente | The added value of LinkedIn depends on how I manage it personally |

| 12 | Si tuviera que buscar un nuevo empleo, utilizaría LinkedIn para ello | If I had to look for a new job, I would use LinkedIn |

| 13 | Tener un perfil actualizado en LinkedIn puede ayudarme a encontrar un empleo | Having an updated profile on LinkedIn can help me find a job |

| 14 | En caso de que tuviera una empresa, crearía un perfil de LinkedIn específico sobre la misma | If I had a company, I would create a specific LinkedIn profile for it |

| 15 | En caso de que tuviera una empresa, LinkedIn me ayudaría a que ésta tuviese más éxito | If I had a company, LinkedIn would help me make it more successful |

| 16 | Saber gestionar LinkedIn puede facilitarme emprender | Knowing how to manage LinkedIn can facilitate me to become an entrepreneur |

| 17 | Creo que LinkedIn es un medio social muy recomendable para los gestores del deporte | I believe that LinkedIn is a highly recommended social media for sport managers |

References

- Liguori, E.; Winkler, C. From Offline to Online: Challenges and Opportunities for Entrepreneurship Education Following the COVID-19 Pandemic. Entrep. Educ. Pedagog. 2020, 3, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secundo, G.; Gioconda, M.; Del Vecchio, P.; Gianluca, E.; Margherita, A.; Valentina, N. Threat or Opportunity? A Case Study of Digital-Enabled Redesign of Entrepreneurship Education in the COVID-19 Emergency. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 166, 120565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V. Coronavirus (COVID-19) and the Entrepreneurship Education Community. J. Enterp. Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2020, 14, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, N.; Çubukçuoğlu, B.; Elçi, A. Using Social Media to Support Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: An Analysis of Personal Narratives. Res. Learn. Technol. 2020, 28, 2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Educational Disruption and Response. UNESCO. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/news/covid-19-educational-disruption-and-response (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Williamson, B.; Eynon, R.; Potter, J. Pandemic Politics, Pedagogies and Practices: Digital Technologies and Distance Education during the Coronavirus Emergency. Learn. Media Technol. 2020, 45, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V.; Jones, P. COVID-19 and Entrepreneurship Education: Implications for Advancing Research and Practice. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2020, 100432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, B.; Grippa, F. A Platform for AI-Enabled Real-Time Feedback to Promote Digital Collaboration. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukendro, S.; Habibi, A.; Khaeruddin, K.; Indrayana, B.; Syahruddin, S.; Makadada, F.A.; Hakim, H. Using an Extended Technology Acceptance Model to Understand Students’ Use of e-Learning during COVID-19: Indonesian Sport Science Education Context. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Ayoob, T.; Malik, A.; Memon, S.I. Perceptions of Students Regarding E-Learning during COVID-19 at a Private Medical College. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 36, S57–S61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamadi, M.; El-Den, J.; Narumon Sriratanaviriyakul, C.; Azam, S.A. Social Media Adoption Framework as Pedagogical Instruments in Higher Education Classrooms. E-Learn. Digit. Media 2021, 18, 55–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manca, S.; Ranieri, M. Is Facebook Still a Suitable Technology-Enhanced Learning Environment? An Updated Critical Review of the Literature from 2012 to 2015. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2016, 32, 503–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Carril, S.; Añó, V.; González-Serrano, M.H. Introducing TED Talks as a Pedagogical Resource in Sport Management Education through YouTube and LinkedIn. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goal 4 Ensure Inclusive and Equitable Quality Education and Promote Lifelong Learning Opportunities for All. United Nations. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal4 (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- Badoer, E.; Hollings, Y.; Chester, A. Professional Networking for Undergraduate Students: A Scaffolded Approach. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2020, 45, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komljenovic, J. Linkedin, Platforming Labour, and the New Employability Mandate for Universities. Glob. Soc. Educ. 2019, 17, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Serrano, M.H.; Moreno, F.C.; Hervás, J.C. Sport Management Education through an Entrepreneurial Perspective: Analysing Its Impact on Spanish Sports Science Students. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2018, 100271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pate, J.R.; Bosley, A.T. Understanding the Skills and Competencies Athletic Department Social Media Staff Seek in Sport Management Graduates. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2020, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tess, P.A. The Role of Social Media in Higher Education Classes (Real and Virtual)—A Literature Review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, A60–A68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodyear, V.A.; Casey, A.; Kirk, D. Tweet Me, Message Me, like Me: Using Social Media to Facilitate Pedagogical Change within an Emerging Community of Practice. Sport Educ. Soc. 2014, 19, 927–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secundo, G.; Del Vecchio, P.; Mele, G. Social Media for Entrepreneurship: Myth or Reality? A Structured Literature Review and a Future Research Agenda. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 1, 149–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escamilla-Fajardo, P.; Núñez-Pomar, J.M.; Calabuig-Moreno, F.; Gómez-Tafalla, A.M. Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Sports Entrepreneurship. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filo, K.; Lock, D.; Karg, A. Sport and Social Media Research: A Review. Sport Manag. Rev. 2015, 18, 166–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Carril, S.; Anagnostopoulos, C.; Parganas, P. Social Media in Sport Management Education: Introducing LinkedIn. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2020, 27, 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naraine, M.L.; Wear, H.T.; Whitburn, D.J. User Engagement from within the Twitter Community of Professional Sport Organizations. Manag. Sport Leis. 2019, 24, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, K.; Danylchuk, K.; Millar, P. Social Media as a Learning Tool: Sport Management Faculty Perceptions of Digital Pedagogies. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2015, 9, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marr, J.; DeWaele, C.S. Incorporating Twitter within the Sport Management Classroom: Rules and Uses for Effective Practical Application. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2015, 17, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slone, A.R.; Gaffney, A.L. Assessing Students’ Use of LinkedIn in a Business and Professional Communication Course. Commun. Teach. 2016, 30, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. Auditing the “Me Inc.”: Teaching Personal Branding on LinkedIn through an Experiential Learning Method. Commun. Teach. 2021, 35, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, J.G. Linking in with LinkedIn®: Three Exercises That Enhance Professional Social Networking and Career Building. J. Manag. Educ. 2012, 36, 866–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.M.; Dover, H.F. Building Student Networks with LinkedIn: The Potential for Connections, Internships, and Jobs. Mark. Educ. Rev. 2014, 24, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmack, H.J.; Heiss, S.N. Using the Theory of Planned Behavior to Predict College Students’ Intent to Use LinkedIn for Job Searches and Professional Networking. Commun. Stud. 2018, 69, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijck, J. “You Have One Identity”: Performing the Self on Facebook and LinkedIn. Media Cult. Soc. 2013, 35, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florenthal, B. Applying Uses and Gratifications Theory to Students’ LinkedIn Usage. Young Consum. 2015, 16, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCorkle, D.E.; McCorkle, Y.L. Using LinkedIn in the Marketing Classroom: Exploratory Insights and Recommendations for Teaching Social Media/Networking. Mark. Educ. Rev. 2012, 22, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice-Hall: Hemel Hempstead, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hagstrom, F.; Wertsch, J.V. Grounding Social Identity for Professional Practice. Top. Lang. Disord. 2004, 24, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaget, J. The Fourth Stage: The Coordination of the Secondary Schemata and Their Application to New Situations. In The Origins of Intelligence in Children; Piaget, J., Cook, M., Eds.; W. W. Norton & Co: New York, NY, USA, 1952; pp. 210–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karns, G.L. Learning Style Differences in the Perceived Effectiveness of Learning Activities. J. Mark. Educ. 2006, 28, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, R.G. Engaging Students in Active Learning. Campus 1997, 2, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, B.S.; Engelhart, M.D.; Furst, E.J.; Hill, W.H.; Krathwohl, D.R. Taxonomy of Educational Objetives: The Classification of Educational Goals: Handbook I: Cognitive Domain; David McKay Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Hamadi, M.; El-Den, J.; Azam, S.; Sriratanaviriyakul, N. Integrating Social Media as Cooperative Learning Tool in Higher Education Classrooms: An Empirical Study. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Pederson, J.A. LinkedIn to Classroom Community: Assessing Classroom Community on the Basis of Social Media Usage. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2020, 44, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonell, J. La Aventura de Innovar: El Cambio En La Escuela; Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Imbernón, F. En Busca Del Discurso Educativo: La Escuela, La Innovación Educativa, El Currículum, El Maestro y Su Formación; Magisterio del Río de la Plata: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, O.K.M.; Stanway, A.R. Tweeting the Lecture: How Social Media Can Increase Student Engagement in Higher Education. Sport Manag. Educ. J. 2015, 9, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, B.; Raes, A.; Montrieux, H.; Schellens, T. “Pedagogical Tweeting” in Higher Education: Boon or Bane? Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2018, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, C.-P.; Bentler, P.M. Estimates and Tests in Structural Equation Modeling. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 37–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F. A Second Generation Little Jiffy. Psychometrika 1970, 35, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrando, P.J.; Anguiano-Carrasco, C. El Análisis Factorial Como Técnica de Investigación En Psicología. Pap. Psicol. 2010, 31, 18–33. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, L.S.; Gamst, G.; Guarino, A.J. Applied Multivariate Research: Design and Interpretation; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Satorra, A.; Bentler, P.M. Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In Latent Variables Analysis: Applications for Developmental Research; von Eye, A., Clogg, C.C., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 399–419. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton, B.; Muthen, B.; Alwin, D.F.; Summers, G.F. Assessing Reliability and Stability in Panel Models. Sociol. Methodol. 1977, 8, 84–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Austin, J.T. Applications of Structural Equation Modeling in Psychological Research. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2000, 51, 201–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W.; Cudeck, R.; Bollen, K.A.; Long, J.S. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Testing Structural Equation Models; Bollen, K.A., Long, J.S., Eds.; Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1993; pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J.; Shavelson, R.J. My Current Thoughts on Coefficient Alpha and Successor Procedures. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2004, 64, 391–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Market. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, D.; Thompson, H.; Higgins, C.M. The Partial Least Squares (PLS) Approach to Causal Modeling: Personal Computer Use as an Illustration. Technol. Stud. 1995, 2, 285–323. [Google Scholar]

- Benson, V.; Morgan, S.; Filippaios, F. Social Career Management: Social Media and Employability Skills Gap. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 30, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| W’s | Key Points |

|---|---|

| What | An educational innovation through LinkedIn in a sport management course |

| Who | 110 third-year undergraduate students (90 men and 20 women) from the University of Valencia (Spain) |

| Why | To develop student’s professional profiles and offer them learning opportunities where they can interact and network with the sports industry, peers and faculty which can be important for their future career |

| Where | On LinkedIn, mainly in the course groups (i.e., “SMval”, “SMont” and “Sport Management Lovers”), on the student’s profiles and on the LinkedIn “wall” where content is created and shared |

| When | 2nd semester (February–May) of the academic course 2018–2019 |

| How | Through experiential learning, a LinkedIn assignment was designed where the student is the protagonist, completing specific tasks in private class groups, on their profile, and within their network of contacts. |

| Item No. | Item | Origin of the Item |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | LinkedIn is a good tool to keep informed about sport management issues | Adams et al. [47] |

| 2 | LinkedIn can help keep you up to date on the latest developments in the sports industry | Scott and Stanway [46] |

| 3 | LinkedIn will make it easier for me to be connected with stakeholders from the sport industry (clubs, sport managers, sport entities, sport companies, etc.) | Scott and Stanway [46] |

| 4 | LinkedIn gives you the opportunity to follow and/or be connected with relevant people in my professional sector | Adams et al. [47] |

| 5 | LinkedIn can be useful to reflect critically on issues related to sport management | Adams et al. [47] |

| 6 | LinkedIn facilitates discussions with professionals on sports industry topics that interest me | Adams et al. [47] |

| 7 | I believe that companies are able to appreciate that I know how to manage LinkedIn | New item |

| 8 | LinkedIn can be useful to expand my professional network | Adams et al. [47] |

| 9 | Learning to use LinkedIn could be an experience that will help me in my professional future | Adams et al. [47] |

| 10 | I believe that learning to use LinkedIn will be positive for my professional future | New item |

| 11 | The added value of LinkedIn depends on how I manage it personally | Adams et al. [47] |

| 12 | If I had to look for a new job, I would use LinkedIn | New item |

| 13 | Having an updated profile on LinkedIn can help me find a job | New item |

| 14 | If I had a company, I would create a specific LinkedIn profile for it | New item |

| 15 | If I had a company, LinkedIn would help me make it more successful | New item |

| 16 | Knowing how to manage LinkedIn can facilitate me to become an entrepreneur | New item |

| 17 | I believe that LinkedIn is a highly recommended social media for sport managers | New item |

| Item No. | Item | M | SD | Asymmetry | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LinkedIn is a good tool to keep informed about sport management issues | 3.57 | 0.72 | 0.32 | −0.34 |

| 2 | LinkedIn can help keep you up to date on the latest developments in the sports industry | 3.60 | 0.68 | 0.25 | −0.22 |

| 3 | LinkedIn will make it easier for me to be connected with stakeholders from the sport industry (clubs, sport managers, sport entities, sport companies, etc.) | 3.79 | 0.73 | −0.01 | −0.43 |

| 4 | LinkedIn gives you the opportunity to follow and/or be connected with relevant people in my professional sector | 3.89 | 0.76 | 0.03 | −0.87 |

| 5 | LinkedIn can be useful to reflect critically on issues related to sport management | 3.54 | 0.67 | 0.63 | −0.34 |

| 6 | LinkedIn facilitates discussions with professionals on sports industry topics that interest me | 3.62 | 0.68 | 0.42 | −0.50 |

| 7 | I believe that companies are able to appreciate that I know how to manage LinkedIn | 3.73 | 0.73 | 0.11 | −0.53 |

| 8 | LinkedIn can be useful to expand my professional network | 3.92 | 0.77 | −0.18 | −0.93 |

| 9 | Learning to use LinkedIn could be an experience that will help me in my professional future | 3.83 | 0.77 | −0.01 | −0.69 |

| 10 | I believe that learning to use LinkedIn will be positive for my professional future | 3.82 | 0.79 | −0.24 | 0.41 |

| 11 | The added value of LinkedIn depends on how I manage it personally | 3.80 | 0.74 | 0.34 | −1.09 |

| 12 | If I had to look for a new job, I would use LinkedIn | 3.32 | 0.85 | 0.12 | 0.56 |

| 13 | Having an updated profile on LinkedIn can help me find a job | 3.88 | 0.79 | 0.22 | −1.36 |

| 14 | If I had a company, I would create a specific LinkedIn profile for it | 3.68 | 0.85 | 0.33 | −0,97 |

| 15 | If I had a company, LinkedIn would help me make it more successful | 3.51 | 0.75 | 0.93 | −0.34 |

| 16 | Knowing how to manage LinkedIn can facilitate me to become an entrepreneur | 3.62 | 0.74 | 0.58 | −0.68 |

| 17 | I believe that LinkedIn is a highly recommended social media for sport managers | 3.66 | 0.75 | 0.51 | −0.79 |

| Item No. | Items (17 Items, 2 Dimensions) | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | LinkedIn is a good tool to keep informed about sport management issues | 0.83 | |

| 2 | LinkedIn can help keep you up to date on the latest developments in the sports industry | 0.87 | |

| 3 | LinkedIn will make it easier for me to be connected with stakeholders from the sport industry (clubs, sport managers, sport entities, sport companies, etc.) | 0.89 | |

| 4 | LinkedIn gives you the opportunity to follow and/or be connected with relevant people in my professional sector | 0.87 | |

| 5 | LinkedIn can be useful to reflect critically on issues related to sport management | 0.71 | |

| 6 | LinkedIn facilitates discussions with professionals on sports industry topics that interest me | 0.83 | |

| 7 | I believe that companies are able to appreciate that I know how to manage LinkedIn | 0.61 | |

| 8 | LinkedIn can be useful to expand my professional network | 0.47 | 0.45 |

| 9 | Learning to use LinkedIn could be an experience that will help me in my professional future | 0.63 | |

| 10 | I believe that learning to use LinkedIn will be positive for my professional future | 0.52 | |

| 11 | The added value of LinkedIn depends on how I manage it personally | 0.67 | |

| 12 | If I had to look for a new job, I would use LinkedIn | 0.68 | |

| 13 | Having an updated profile on LinkedIn can help me find a job | 0.95 | |

| 14 | If I had a company, I would create a specific LinkedIn profile for it | 0.88 | |

| 15 | If I had a company, LinkedIn would help me make it more successful | 0.90 | |

| 16 | Knowing how to manage LinkedIn can facilitate me to become an entrepreneur | 0.90 | |

| 17 | I believe that LinkedIn is a highly recommended social media for sport managers | 0.60 | |

| % explained variance | 58.38 | 10.40 | |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.95 | ||

| Eingenvalue | 9.34 | ||

| Total explained variance | 68.78% | ||

| Item No. | Items (16 Items, 2 Dimensions) | M | SD | rjx | α − x |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension 1: LinkedIn as a tool to keep up to date and interact with the sports industry (α = 0.93); M = 3.68; SD = 0.60 | |||||

| 1 | LinkedIn is a good tool to keep informed about sport management issues | 3.57 | 0.72 | 0.83 | 0.92 |

| 2 | LinkedIn can help keep you up to date on the latest developments in the sports industry | 3.60 | 0.68 | 0.76 | 0.92 |

| 3 | LinkedIn will make it easier for me to be connected with stakeholders from the sport industry (clubs, sport managers, sport entities, sport companies, etc.) | 3.79 | 0.73 | 0.88 | 0.91 |

| 4 | LinkedIn gives you the opportunity to follow and/or be connected with relevant people in my professional sector | 3.89 | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.92 |

| 5 | LinkedIn can be useful to reflect critically on issues related to sport management | 3.54 | 0.67 | 0.76 | 0.92 |

| 6 | LinkedIn facilitates discussions with professionals on sports industry topics that interest me | 3.62 | 0.68 | 0.71 | 0.93 |

| 7 | I believe that companies are able to appreciate that I know how to manage LinkedIn | 3.73 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.93 |

| Dimension 2: LinkedIn as a driver of career development (α = 0.92); M = 3.70; SD = 0.63 | |||||

| 9 | Learning to use LinkedIn could be an experience that will help me in my professional future | 3.83 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.91 |

| 10 | I believe that learning to use LinkedIn will be positive for my professional future | 3.82 | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.91 |

| 11 | The added value of LinkedIn depends on how I manage it personally | 3.80 | 0.74 | 0.58 | 0.92 |

| 12 | If I had to look for a new job, I would use LinkedIn | 3.32 | 0.85 | 0.60 | 0.92 |

| 13 | Having an updated profile on LinkedIn can help me find a job | 3.88 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.91 |

| 14 | If I had a company, I would create a specific LinkedIn profile for it | 3.68 | 0.85 | 0.74 | 0.91 |

| 15 | If I had a company, LinkedIn would help me make it more successful | 3.51 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.91 |

| 16 | Knowing how to manage LinkedIn can facilitate me to become an entrepreneur | 3.62 | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.91 |

| 17 | I believe that LinkedIn is a highly recommended social media for sport managers | 3.66 | 0.75 | 0.78 | 0.91 |

| Item No. | Items (16 Items, 2 Dimensions) | λ | CR | AVE | Square Root AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension 1: LinkedIn as a tool to keep up to date and interact with the sports industry (M = 3.68, DT = 0.60; alfa = 0.93) | |||||

| 1 | LinkedIn is a good tool to keep informed about sport management issues | 0.869 | 0.93 | 0.66 | 0.82 |

| 2 | LinkedIn can help keep you up to date on the latest developments in the sports industry | 0.775 | |||

| 3 | LinkedIn will make it easier for me to be connected with stakeholders from the sport industry (clubs, sport managers, sport entities, sport companies, etc.) | 0.918 | |||

| 4 | LinkedIn gives you the opportunity to follow and/or be connected with relevant people in my professional sector | 0.836 | |||

| 5 | LinkedIn can be useful to reflect critically on issues related to sport management | 0.797 | |||

| 6 | LinkedIn facilitates discussions with professionals on sports industry topics that interest me | 0.725 | |||

| 7 | I believe that companies are able to appreciate that I know how to manage LinkedIn | 0.779 | |||

| Dimension 2: LinkedIn as a driver of career development (M = 3.64, DT = 0.63; alfa = 0.91) | |||||

| 9 | Learning to use LinkedIn could be an experience that will help me in my professional future | 0.812 | 0.92 | 0.57 | 0.75 |

| 10 | I believe that learning to use LinkedIn will be positive for my professional future | 0.719 | |||

| 11 | The added value of LinkedIn depends on how I manage it personally | 0.619 | |||

| 12 | If I had to look for a new job, I would use LinkedIn | 0.619 | |||

| 13 | Having an updated profile on LinkedIn can help me find a job | 0.790 | |||

| 14 | If I had a company, I would create a specific LinkedIn profile for it | 0.749 | |||

| 15 | If I had a company, LinkedIn would help me make it more successful | 0.771 | |||

| 16 | Knowing how to manage LinkedIn can facilitate me to become an entrepreneur | 0.817 | |||

| 17 | I believe that LinkedIn is a highly recommended social media for sport managers | 0.845 |

| Dimensions | Dimension 1: LinkedIn as a Tool to Keep up to Date and Interact with the Sports Industry | Dimension 2: LinkedIn as a Driver of Career Development |

|---|---|---|

| Dimension 1: LinkedIn as a tool to keep up to date and interact with the sports industry | 0.82 | |

| Dimension 2: LinkedIn as a driver of career development | 0.73 *** | 0.75 |

| Item No. | Dimensions | Pre-Test M (SD) | Post-Test M (SD) | Z | p | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension 1: LinkedIn as a tool to keep up to date and interact with the sports industry | 3.68 (0.60) | 4.23 (0.48) | −4.65 | 0.000 | 0.98 | |

| 1 | LinkedIn is a good tool to keep informed about sport management issues | 3.57 (0.72) | 4.24 (0.64) | −4.42 | 0.000 | 0.99 |

| 2 | LinkedIn can help keep you up to date on the latest developments in the sports industry | 3.60 (0.68) | 4.17 (0.67) | −4.18 | 0.000 | 0.84 |

| 3 | LinkedIn will make it easier for me to be connected with stakeholders from the sport industry (clubs, sport managers, sport entities, sport companies, etc.) | 3.79 (0.73) | 4.28 (0.59) | −3.88 | 0.000 | 0.74 |

| 4 | LinkedIn gives you the opportunity to follow and/or be connected with relevant people in my professional sector | 3.89 (0.76) | 4.32 (0.55) | −3.16 | 0.002 | 0.65 |

| 5 | LinkedIn can be useful to reflect critically on issues related to sport management | 3.54 (0.67) | 4.24 (0.59) | −4.77 | 0.000 | 0.98 |

| 6 | LinkedIn facilitates discussions with professionals on sports industry topics that interest me | 3.62 (0.68) | 4.19 (0.66) | −4.38 | 0.000 | 0.85 |

| 7 | I believe that companies are able to appreciate that I know how to manage LinkedIn | 3.73 (0.73) | 4.21 (0.60) | −3.67 | 0.000 | 0.72 |

| Dimension 2: LinkedIn as a driver of career development | 3.70 (0.63) | 4.12 (0.49) | −3.95 | 0.000 | 0.80 | |

| 9 | Learning to use LinkedIn could be an experience that will help me in my professional future | 3.83 (0.77) | 4.22 (0.66) | −3.10 | 0.002 | 0.54 |

| 10 | I believe that learning to use LinkedIn will be positive for my professional future | 3.82 (0.79) | 4.24 (0.59) | −3.12 | 0.002 | 0.60 |

| 11 | The added value of LinkedIn depends on how I manage it personally | 3.80 (0.74) | 4.17 (0.67) | −2.36 | 0.018 | 0.52 |

| 12 | If I had to look for a new job, I would use LinkedIn | 3.32 (0.85) | 3.86 (0.78) | −3.00 | 0.003 | 0.66 |

| 13 | Having an updated profile on LinkedIn can help me find a job | 3.88 (0.79) | 4.17 (0.69) | −2.02 | 0.044 | 0.39 |

| 14 | If I had a company, I would create a specific LinkedIn profile for it | 3.68 (0.85) | 4.06 (0.75) | −2.68 | .007 | 0.47 |

| 15 | If I had a company, LinkedIn would help me make it more successful | 3.51 (0.75) | 4.07 (0.61) | −4.27 | 0.000 | 0.82 |

| 16 | Knowing how to manage LinkedIn can facilitate me to become an entrepreneur | 3.62 (0.74) | 4.13 (0.67) | −3.59 | 0.000 | 0.72 |

| 17 | I believe that LinkedIn is a highly recommended social media for sport managers | 3.66 (0.75) | 4.21 (0.60) | −4.00 | 0.000 | 0.81 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López-Carril, S.; Villamón, M.; González-Serrano, M.H. Linked(In)g Sport Management Education with the Sport Industry: A Preliminary Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2275. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042275

López-Carril S, Villamón M, González-Serrano MH. Linked(In)g Sport Management Education with the Sport Industry: A Preliminary Study. Sustainability. 2021; 13(4):2275. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042275

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez-Carril, Samuel, Miguel Villamón, and María Huertas González-Serrano. 2021. "Linked(In)g Sport Management Education with the Sport Industry: A Preliminary Study" Sustainability 13, no. 4: 2275. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042275

APA StyleLópez-Carril, S., Villamón, M., & González-Serrano, M. H. (2021). Linked(In)g Sport Management Education with the Sport Industry: A Preliminary Study. Sustainability, 13(4), 2275. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042275