An Integrated Approach to Assess Potential and Sustainability of Handmade Carpet Production in Different Areas of the East Azerbaijan Province of Iran

Abstract

1. Introduction

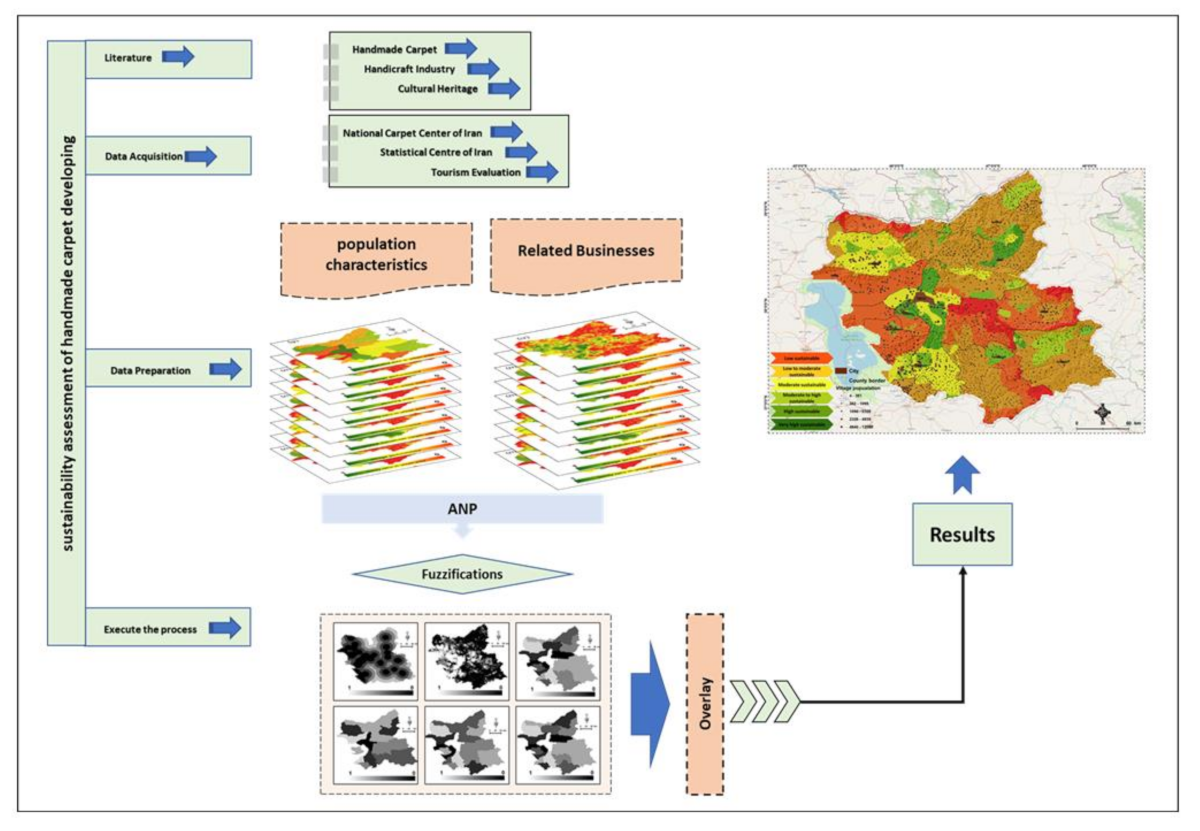

2. Materials and Methods

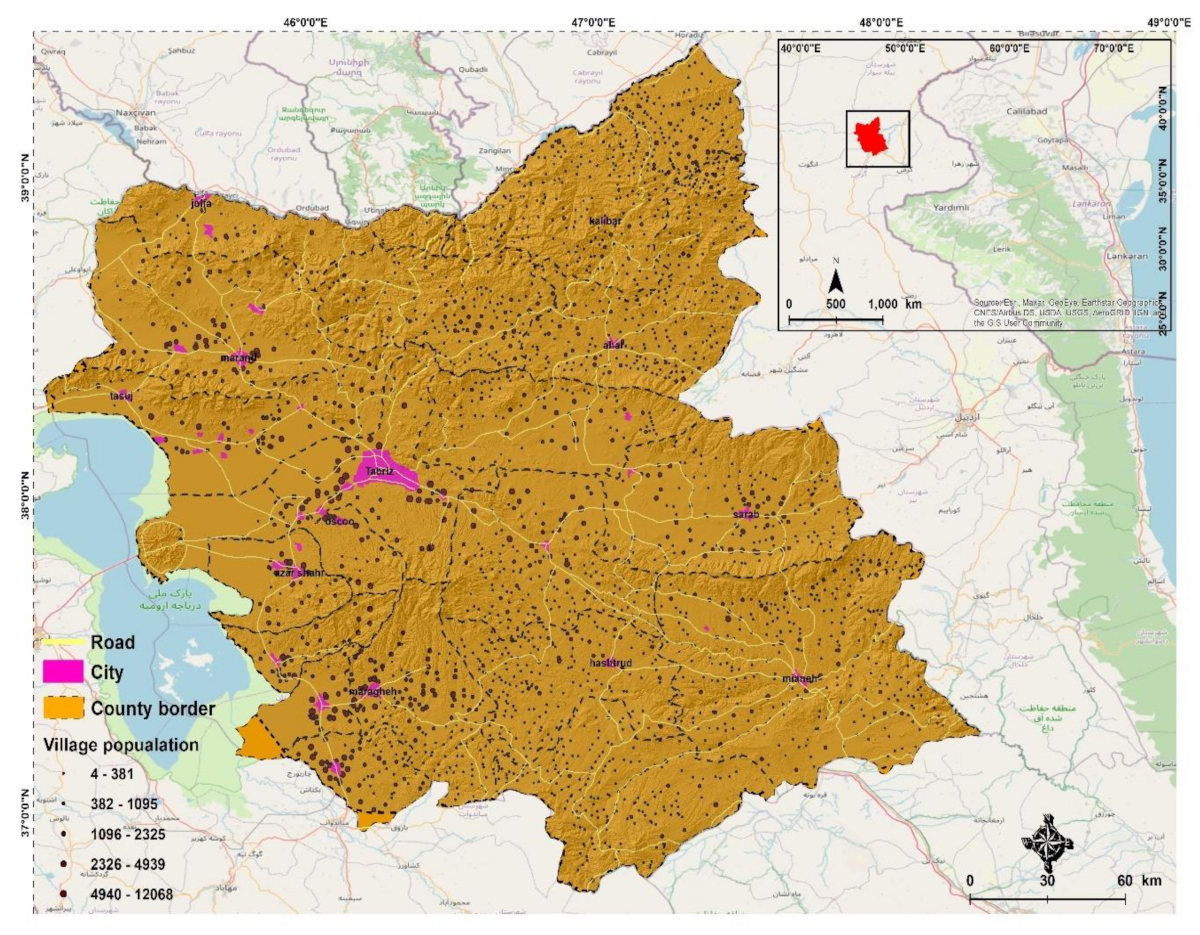

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Dataset

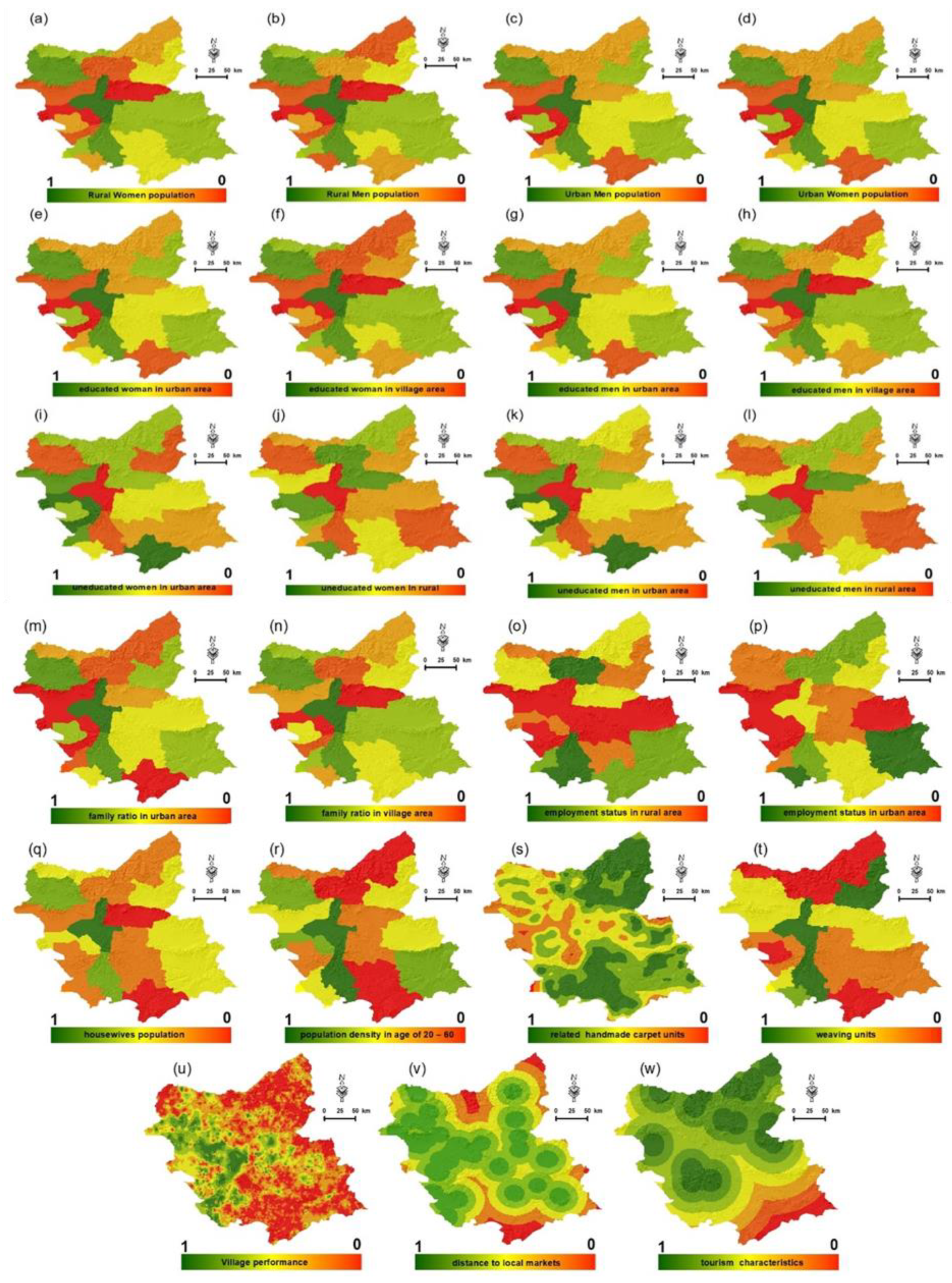

2.3. Criteria Selection and Data Evaluation

2.3.1. Population Characteristics

2.3.2. Education Status

2.3.3. Employments Status

2.3.4. Related Businesses

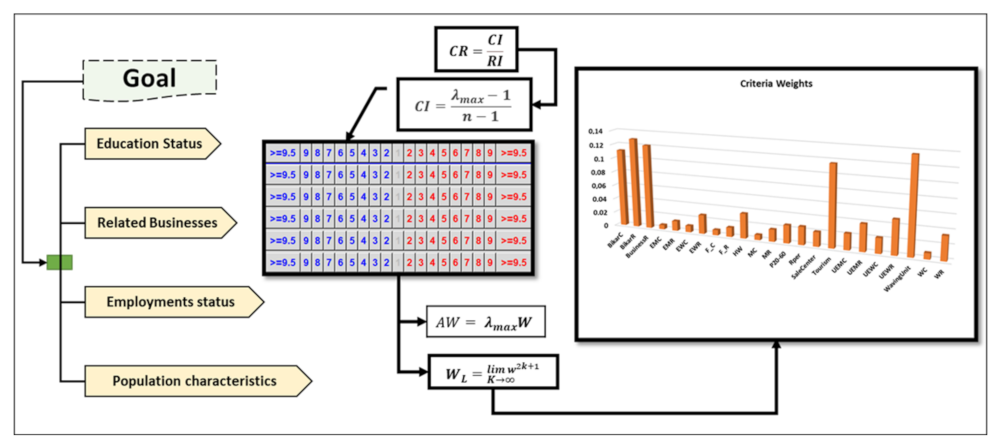

2.4. Methodology

2.4.1. Assigning Weights to the Criteria Using Analytical Network Process

2.4.2. Fuzzification and Aggregation

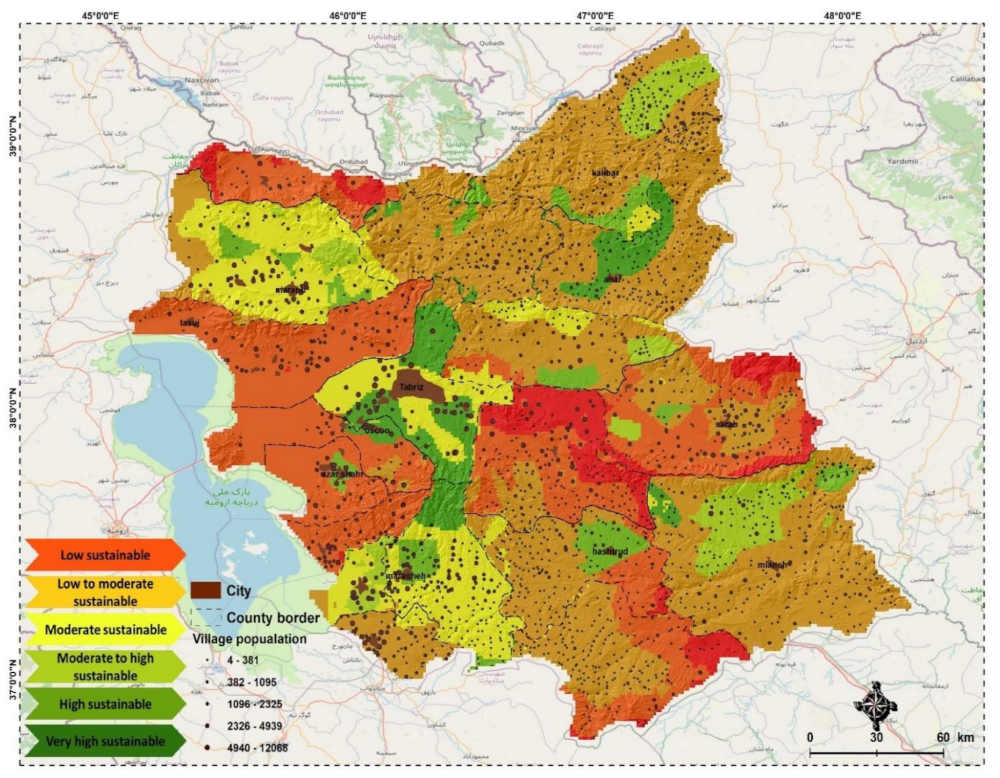

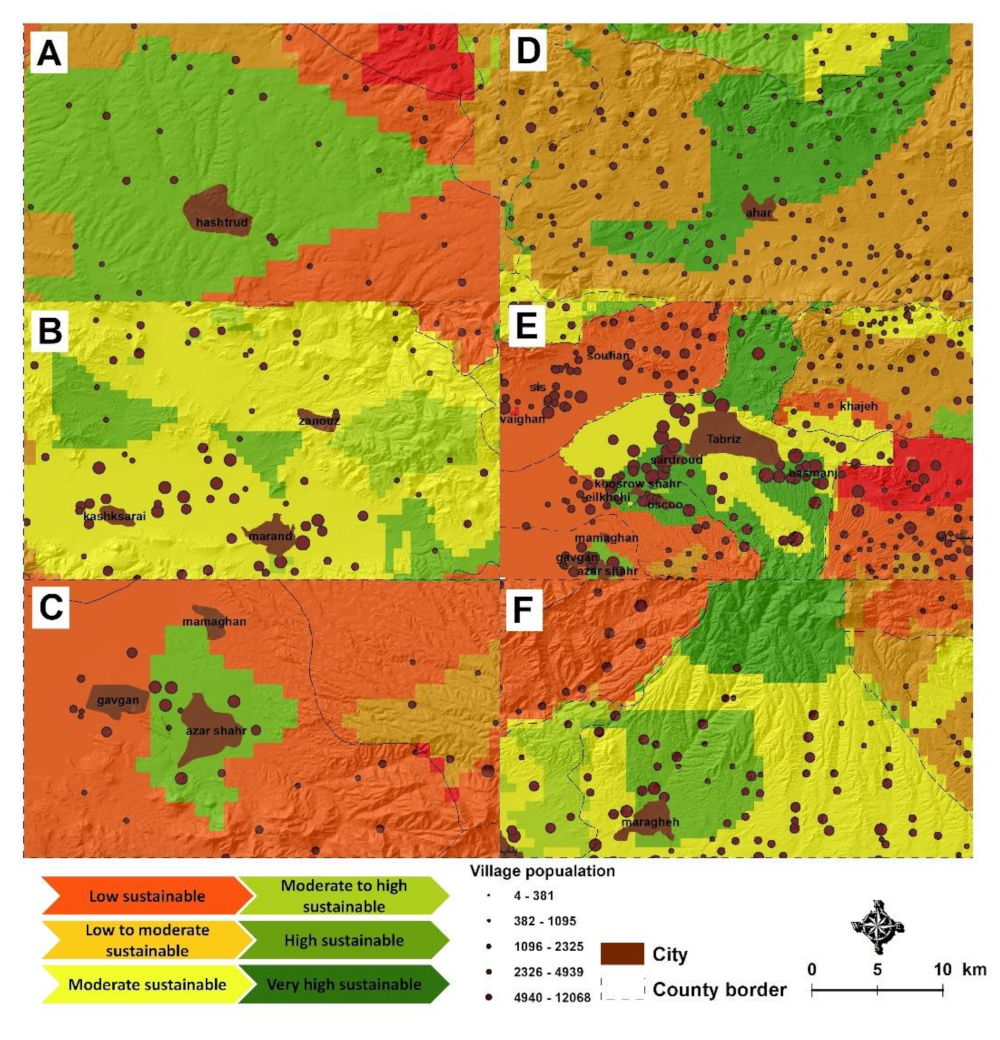

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, Y.; Shafi, M.; Song, X.; Yang, R. Preservation of cultural heritage embodied in traditional crafts in the developing countries: A case study of Pakistani handicraft industry. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihatsu, A.-M. Making Sense of Contemporary American Craft; University of Joensuu Publications in Education No 73; University of Joensuu: Joensuu, Finland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kokko, S. Learning practices of femininity through gendered craft education in Finland. Gend. Educ. 2009, 21, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokko, S.; Dillon, P. Crafts and craft education as expressions of cultural heritage: Individual experiences and collective values among an international group of women university students. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2011, 21, 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshgar, A. The Art and Industry of Iranian Handmade Carpet; Jahantab Publication: Tehran, Iran, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Persia, D. Persian Rug, a Symbol of Iranian Originality. 2017. Available online: https://www.welcometoiran.com (accessed on 12 March 2017).

- Vandshoari, A. The Status of Mystical Motifs of Battle between Lion and Cow (Gereft-o-Gir) in Four Samples of Safavid Period Carpets. Jelveye Honar Al-Zahra Sci. Promot. Bi-Annu. J. 2011, 2, 39–50. [Google Scholar]

- Heshmati Razavi, F. Carpet History; Samt Publication: Tehran, Iran, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Amini, A.; Nasrabadi, E.; Jafari, T. Structural model of the effect of adaptive sales behavior strategy on marketing effectiveness: The mediating role of marketing emphasis in the art of handmade carpet industry. Goljaam 2018, 33, 105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Shamabadi, M.K.; HodadadHoseini, S.A. Export marketing of Iranian handmade carpets: A study of effective factors and pathology. Bus. Res. J. 2007, 11, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Vandshoari, A.; Nadalian, A. Manifestation of Gnosticism in the Carpet Design of the Safavid period. Anal. Res. Q. J. 2006, 2, 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Iran National Carpet Center. 2020. Available online: https://www.ircpe.com/1135-carpet-weavers-insurance (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Hoseini, E.; Aghayei, M.; Rezaripoor, M. Investigating the comparative advantage of Iran in the production and export of handmade carpets (Case study of Isfahan Province). Econ. J. 2010, 10, 255–283. [Google Scholar]

- Yazdani, M. An Investigation on Influencing Factors on Tourists Shopping: Attitude of Iranian Handmade Carpet in Isfahan. Master’s Thesis, Department of Business Administration and Social Sciences, Luleå University of Technology, Luleå, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hasanzadeh, M.; Faizollahi, M. Investigating the effective factors on the development of handmade carpet exports in the era of resistance economy with a look at Islamic marketing. Q. J. New Res. Manag. Account. 2016, 3. Available online: https://civilica.com/doc/644487 (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Tehrani, P.M.; Manap, N.A. Urgency and benefits of protecting Iranian carpets using geographical indications. J. Intellect. Prop. Rights 2013, 18, 72–82. [Google Scholar]

- Golmeymi, M.; Mirvaisi, M.; Maleki, B.; Aliabadi, Z. An empirical study on the effect of WTO membership on Iranian Handicraft industry: A case study of Persian carpet. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2013, 3, 1375–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Toghraei, M.T.; Navidzadeh, B.; Attafar, A.; Zakariyayi Kermani, I. Identification of Innovation Obstacles in the Design and Production of Isfahan hand-woven Carpets: Entrepreneur’s Approach. Goljaam 2016, 11, 73–91. Available online: http://goljaam.icsa.ir/article-1-237-fa.html (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Poonpol, D.; Panin, K.; Rungruengpol, N.; Phokaratsiri, J. Local Arts and Crafts and Production as Influenced by Cultural Ecology; Unpublished Monograph; Institute of Research and Development, Silpakorn University: Bangkok, Thailand, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Barrère, C. Cultural heritages: From official to informal. City Cult. Soc. 2016, 7, 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Why Safeguard Intangible Cultural Heritage? Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/why-safeguard-ich-00479 (accessed on 22 December 2017).

- Hani, U.; Azzadina, I.; Sianipar, C.P.M.; Setyagung, E.H.; Ishii, T. Preserving Cultural Heritage through Creative Industry: A Lesson from Saung Angklung Udjo. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2012, 4, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafournia, M.; Vesali, N. Investigating factors affecting the European: Union: Importers’ buying decision making to buy Iranian handmade carpet. J. Sci. Goljaam 2018, 14, 125–144. [Google Scholar]

- Omid, A.; Zegordi, S.H. Integrated AHP and network DEA for assessing the efficiency of Iranian handmade carpet industry. Decis. Sci. Lett. 2015, 4, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavandi, Z.; Mazroui Nasrabadi, E. Designing a Model for Cooperation-competition Incentives (Case Study: Iranian Handmade Carpet Art-industry). J. Bus. Manag. 2020, 12, 357–377. [Google Scholar]

- García-Villaverde, P.M.; Elche, D.; Martínez-Pérez, Á.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.J. Determinants of radical innovation in clustered firms of the hospitality and tourism industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 61, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghapouramin, K. Technical, Economical, and Environmental Feasibility of Hybrid Renewable Electrification Systems for off-Grid Remote Rural Electrification Areas for East Azerbaijan Province, Iran. Technol. Econ. Smart Grids Sustain. Energy 2020, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MCHTH, Ministry of Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Handicrafts. Carpets of Tabriz (The Global City of Hand-Woven Rugs). 2020. Available online: https://www.visitiran.ir (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Tahbaz, A.; Mazaheri Tehrani, M. An Introduction Characteristics of Precious Carpet of Tabriz (Throughout the Past Two Decades). Goljaam 2008, 10, 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ronizi, S.R.A.; Mokarram, M.; Negahban, S. Utilizing multi-criteria decision to determine the best location for the ecotourism in the east and central of Fars province, Iran. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamgosar, M.; Haghyghy, M.; Mehrdoust, F.; Arshad, N. Multicriteria decision making based on analytical hierarchy process (AHP) in GIS for tourism. Middle-East J. Sci. Res. 2011, 10, 501–507. [Google Scholar]

- Feizizadeh, B.; Blaschke, T.; Shadman Roodposhti, M. Integration of GIS based Fuzzy set theory and Multicriteria Evaluation methods for Landslide Susceptibility Mapping. Int. J. Geoinform. 2013, 9, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Feizizadeh, B.; Blaschke, T. GIS-multicriteria decision analysis for landslide susceptibility mapping: Comparing three methods for the Urmia lake basin, Iran. Nat. Hazards 2013, 65, 2105–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi, A.; Niknejad, M.; Karami, O. A fuzzy multi-criteria decision method for ecotourism development locating. Casp. J. Environ. Sci. 2015, 13, 221–236. [Google Scholar]

- Feizizadeh, B.; Gheshlaghi, H.A.; Bui, D.T. An integrated approach of GIS and hybrid intelligence techniques applied for flood risk modeling. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021, 64, 485–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headey, D.D.; Hodge, A. The Effect of Population Growth on Economic Growth: A Meta-Regression Analysis of the Macroeconomic Literature. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2009, 35, 221–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebikabu, D.R.; Ruvuna, E.; Ruzima, M. Population Growth’s Effect on Economic Development in Rwanda. In Rwandan Economy at the Crossroads of Development; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 73–95. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S. Demographic Changes and Economic Growth: Empirical Evidence from Asia; Illinois Wesleyan University: Bloomington, IL, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Adewole, A.O. Effect of population on economic development in Nigeria: A quantitative assessment. Int. J. Phys. Soc. Sci. 2012, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Shaari, M.S.; Rahim, H.A.; Rashid, I.M. Relationship among population, energy consumption and economic growth in Malaysia. The International Journal of Significance. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2013, 34, 17–51. [Google Scholar]

- Tartiyus, E.H.; Dauda, T.M.; Peter, A. Impact of population growth on economic growth in Nigeria. IOSR J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2015, 20, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Linden, E. Remember the Population Bomb? It’s Still Ticking; New York Times: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V.; Kumar, P.; Mishra, M.K. Managing Sustainable Development of Indian Carpet Industry. J. Seybold Rep. 2020, 1533, 9211. [Google Scholar]

- Korneeva, T.A.; Potasheva, O.N.; Tatarovskaya, T.E.; Shatunova, G.A. Human Capital Evaluation in the Digital Economy. In Digital Transformation of the Economy: Challenges, Trends and New Opportunities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Krstic, M.; Filipe, J.A.; Chavaglia, J. Higher Education as a Determinant of the Competitiveness and Sustainable Development of an Economy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorontsova, A.; Mayboroda, T.; Lieonov, H. Innovation management in education: Impact on socio-labour relations in the national economy. Mark. Manag. Innov. 2020, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onifade, S.; Ay, A.; Asongu, S.; Bekun, F. Revisiting the Trade and Unemployment Nexus: Empirical Evidence from the Nigerian Economy. SSRN Electron. J. 2019, e2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization, ILO. World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2019; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-92-2-1329534. [Google Scholar]

- Statistical Center of Iran [SCI]. 2018. Available online: https://www.amar.org.ir/english (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Hwang, J.; Lee, S.W. The effect of the rural tourism policy on non-farm income in South Korea. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, O.; Pourmoradian, S.; Blaschke, T.; Feizizadeh, B. Mapping potential nature-based tourism areas by applying GIS-decision making systems in East Azerbaijan Province, Iran. J. Ecotourism 2019, 18, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheshlaghi, H.A.; Feizizadeh, B. An integrated approach of analytical network process and fuzzy based spatial decision-making systems applied to landslide risk mapping. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2017, 133, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, O.; Feizizadeh, B.; Blaschke, T. An interval matrix method used to optimize the decision matrix in AHP technique for land subsidence susceptibility mapping. Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z. An integrated approach to evaluating the coupling coordination between tourism and the environment. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motlagh, E.Y.; Hajjarian, M.; Zadeh, O.H.; Alijanpour, A. The difference of expert opinion on the forest-based ecotourism development in developed countries and Iran. Land Use Policy 2020, 94, 104549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.T.; Lin, C.W.; Ko, P.H. Application of analytic network process (ANP) in assessing construction risk of urban bridge project. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Innovative Computing, Informatio and Control (ICICIC 2007), Kumamoto, Japan, 5–7 September 2007; p. 169. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, V.Y.; Lien, H.-P.; Liu, C.-H.; Liou, J.J.; Tzeng, G.-H.; Yang, L.-S. Fuzzy MCDM approach for selecting the best environment-watershed plan. Appl. Soft Comput. 2011, 11, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naboureh, A.; Moghaddam, M.H.R.; Feizizadeh, B.; Blaschke, T. An integrated object-based image analysis and CA-Markov model approach for modeling land use/land cover trends in the Sarab plain. Arab. J. Geosci. 2017, 10, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizizadeh, B.; Kienberger, S. Spatially explicit sensitivity and uncertainty analysis for multicriteria-based vulnerability assessment. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2017, 60, 2013–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shokati, B.; Feizizadeh, B. Sensitivity and uncertainty analysis of agro-ecological modeling for saffron plant cultivation using GIS spatial decision-making methods. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2018, 62, 517–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimy, H.; Feizizadeh, B.; Salmani, S.; Azadi, H. A comparative study of land subsidence susceptibility mapping of Tasuj plane, Iran, using boosted regression tree, random forest and classification and regression tree methods. Environ. Earth Sci. 2020, 79, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizizadeh, B.; Ronagh, Z.; Pourmoradian, S.; Gheshlaghi, H.A.; Lakes, T.; Blaschke, T. An efficient GIS-based approach for sustainability assessment of urban drinking water consumption patterns: A study in Tabriz city, Iran. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 64, 102584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoud, R.G.; Farimah, M.R.; Maryam, G. Portfolio selection: A fuzzy-ANP approach. Financ. Innov. 2020, 6, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Fatt, B.S.; Bakansing, S.M. An alternative raw material in handicraft-making by using the oil palm fronds: A community based tourism exploratory study at Kota Belud, Sabah. Tour. Leis. Glob. Chang. 2016, 1, 25–37. [Google Scholar]

- Abisuga-Oyekunle, O.A.; Fillis, I.R. The role of handicraft micro-enterprises as a catalyst for youth employment. Creat. Ind. J. 2017, 10, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazmfar, H.; Alavi, S.; Feizizadeh, B.; Masodifar, R.; Eshghei, A. Spatial Analysis of Security and Insecurity in Urban Parks: A Case Study of Tehran, Iran. Prof. Geogr. 2020, 72, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimzadeh, S.; Feizizadeh, B.; Matsuoka, M. DEM-Based Vs30 Map and Terrain Surface Classification in Nationwide Scale—A Case Study in Iran. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behboudi, D.; Mohammadzadeh, P.; Feizizadeh, B.; Pooranvari, A. Multi-criteria Based Readiness Assessment for Developing Spatial Data Infrastructures in East Azerbaijan Province, Iran. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2018, 2, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Feizizadeh, B.; Kienberger, S.; Kamran, K.V. Sensitivity and Uncertainty Analysis Approach for GIS-MCDA Based Economic Vulnerability Assessment. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2015, 1, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Doaei, H.; Bigham, Z. Feasibility study of implementing electronic marketing in Fars handmade carpet market. New Mark. Res. J. 2015, 5, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Abedi, H.; Feizizadeh, B.; Blaschke, T. GIS-based forest fire risk mapping using the analytical network process and fuzzy logic. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 2020, 481–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohmadzadeh, K.; Feizizadeh, B. Modeling the impacts of Urmia lake drought on soil salinity of agricultural lands in the eastern area of fuzzy object based image analysis approach. J. RS GIS Nat. Resour. 2017, 8, 56–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi, L.; Kamel, B.; Feizizadeh, B. Monitoring Bioenvironmental Impacts of Dam Construction on Land Use Cover Changes in Sattarkhan Basin Using Multi-temporal Satellite Imagery. Iran. J. Energy Environ. 2015, 6, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizizadeh, B.; Blaschke, T.; Nazmfar, H. GIS-based ordered weighted averaging and Dempster–Shafer methods for landslide susceptibility mapping in the Urmia Lake Basin, Iran. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2014, 7, 688–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anvaeri, H.; Feizizadeh, B.; Olyani Nejad, R. Optimum Designing of Gas Distribution Networks of Ilam Province by Using GIS Network and Spatial Analysis. Open J. Geol. 2016, 6, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sadik-Zada, E.R.; Loewenstein, W. Drivers of CO2-Emissions in Fossil Fuel Abundant Settings: (Pooled) Mean Group and Nonparametric Panel Analyses. Energies 2020, 13, 3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadik-Zada, E.R.; Gatto, A. The puzzle of greenhouse gas footprints of oil abundance. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2020, 100936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizizadeh, B.; Blaschke, T.; Nazmafar, H.; Rezaei Mogadam, M.H. Landslide susceptibility mapping using GIS-based Analytical Hierarchical Process for the Urmia Lake basin, Iran. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2013, 7, 3319–3336. [Google Scholar]

- Naboureh, A.; Feizizadeh, B.; Naboureh, A.; Bian, J.; Blaschke, T.; Ghorbanzadeh, O.; Moharami, M. Traffic Accident Spatial Simulation Modeling for Planning of Road Emergency Services. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, O.; Tahmasebipour, N.; Haghizadeh, A.; Pourghasemi, H.R.; Feizizadeh, B. Evaluating the influence of geo-environmental factors on gully erosion in a semi-arid region of Iran: An integrated framework. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 579, 913–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feizizadeh, B.; Blaschke, T.; Tiede, D.; Rezaei Moghaddam, H.M. Evaluation of fuzzy operators within an Object-Based Image Analysis Approach for Landslide change detection analysis. Geomorphology 2017, 293, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, O.; Feizizadeh, B.; Blaschke, T. Multi-criteria risk evaluation by integrating an analytical network process approach into GIS-based sensitivity and uncertainty analyses. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2018, 9, 127–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omarzadeh, D.; Pourmoradian, S.; Feizizadeh, B.; Khallaghi, H.; Sharifi, A.; Valizadeh Kamran, K. A GIS-Based Multiple Ecotourism Sustainability Assessment of West Azerbaijan Province, Iran. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Job Description | Workshops/Unites | Employees |

|---|---|---|

| Concentrated section | 13 | 200 |

| Un/concentrated section | 3854 | 12,180 |

| Workroom | 1749 | 947 |

| Designer | 133 | |

| Generating layout and maps | 7 | |

| Spinning | 69 | 78 |

| Dyeing | 21 | 108 |

| Carpet washing centers | 86 | 186 |

| Raw material distribution | 71 | 935 |

| Accessories distribution | 44 | 121 |

| Carpet weaver | 120,075 | |

| Sum | 5914 | 134,963 |

| Major Criteria | Sub-Criteria Title | Resources |

|---|---|---|

| Population characteristics | Family ratio in urban area | Statistical Centre of Iran, 2016 |

| Family ratio in rural area | ||

| Urban men population | ||

| Rural men population | ||

| Population density in the age of 20–60 | ||

| Urban women population | ||

| Rural women population | Statistical Centre of Iran, 2016 | |

| Education status | Educated men in urban area | |

| Educated men in rural area | ||

| Educated woman in urban area | ||

| Educated woman in rural area | ||

| Uneducated men in urban area | ||

| Uneducated men in rural area | ||

| Uneducated women in urban area | ||

| Uneducated women in rural area | ||

| Employment status | Employment status in urban area | Statistical Centre of Iran, 2016 |

| Employment status in rural area | ||

| Housewife population | ||

| Related Businesses | Related handmade carpet units | Study Result |

| Village performance | Land use planning Scheme | |

| distance to local markets and Trade centers | ||

| Tourism characteristics | ||

| Weaving units | MPO (management and planning organization) 2020 |

| Raw | Equation | Description | Components |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | coefficient index | CI: compatibility index λmax: maximum eigenvalue of the judgment matrix | |

| 2 | compatibility rate | CR: consistency ratio CI: compatibility index RI: random index | |

| 3 | eigenvector matrix | A: pair-wise comparison matrix W: eigenvector λmax: maximum eigenvalue of the judgment matrix | |

| 4 | limit super matrix | W: weighted super matrix K: exponent determined by iteration |

| Cluster | Criteria | ANP Weights |

|---|---|---|

| Population Characteristics | Family ratio in urban area | 0.0076 |

| Family ratio in rural area | 0.0134 | |

| Urban men population | 0.0073 | |

| Rural men population | 0.0173 | |

| Population density in age of 20–60 | 0.0257 | |

| Urban women population | 0.0085 | |

| Rural women population | 0.0341 | |

| Education status | Educated men in urban area | 0.0062 |

| Educated men in rural area | 0.0141 | |

| Educated woman in urban area | 0.0093 | |

| Educated woman in rural area | 0.0272 | |

| Uneducated men in urban area | 0.0231 | |

| Uneducated men in rural area | 0.0387 | |

| Uneducated women in urban area | 0.0218 | |

| Uneducated men in rural area | 0.0491 | |

| Employments status | Employment status in urban area | 0.1115 |

| Employment status in rural area | 0.1291 | |

| House wife population | 0.0357 | |

| Related Business | Related handmade carpet units | 0.1213 |

| Village performance | 0.0258 | |

| Distance to local markets and trade centers | 0.0207 | |

| Tourism characteristics | 0.1160 | |

| Weaving units | 0.1356 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pourmoradian, S.; Vandshoari, A.; Omarzadeh, D.; Sharifi, A.; Sanobuar, N.; Samad Hosseini, S. An Integrated Approach to Assess Potential and Sustainability of Handmade Carpet Production in Different Areas of the East Azerbaijan Province of Iran. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2251. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042251

Pourmoradian S, Vandshoari A, Omarzadeh D, Sharifi A, Sanobuar N, Samad Hosseini S. An Integrated Approach to Assess Potential and Sustainability of Handmade Carpet Production in Different Areas of the East Azerbaijan Province of Iran. Sustainability. 2021; 13(4):2251. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042251

Chicago/Turabian StylePourmoradian, Samereh, Ali Vandshoari, Davoud Omarzadeh, Ayyoob Sharifi, Naser Sanobuar, and Seyyed Samad Hosseini. 2021. "An Integrated Approach to Assess Potential and Sustainability of Handmade Carpet Production in Different Areas of the East Azerbaijan Province of Iran" Sustainability 13, no. 4: 2251. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042251

APA StylePourmoradian, S., Vandshoari, A., Omarzadeh, D., Sharifi, A., Sanobuar, N., & Samad Hosseini, S. (2021). An Integrated Approach to Assess Potential and Sustainability of Handmade Carpet Production in Different Areas of the East Azerbaijan Province of Iran. Sustainability, 13(4), 2251. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042251