A Proposed Conceptual Framework on the Adoption of Sustainable Agricultural Practices: The Role of Network Contact Frequency and Institutional Trust

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

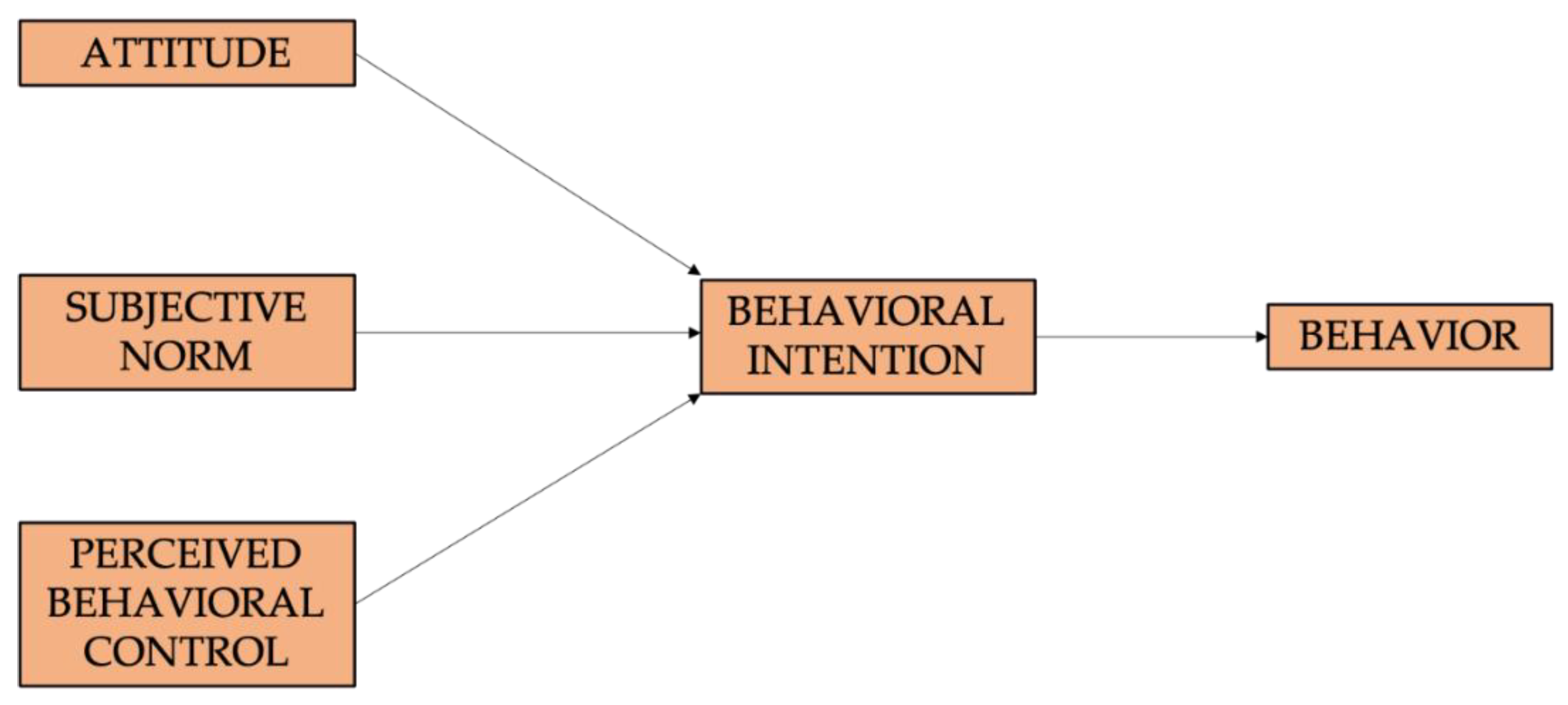

2.1. The Theory of Planned Behavior

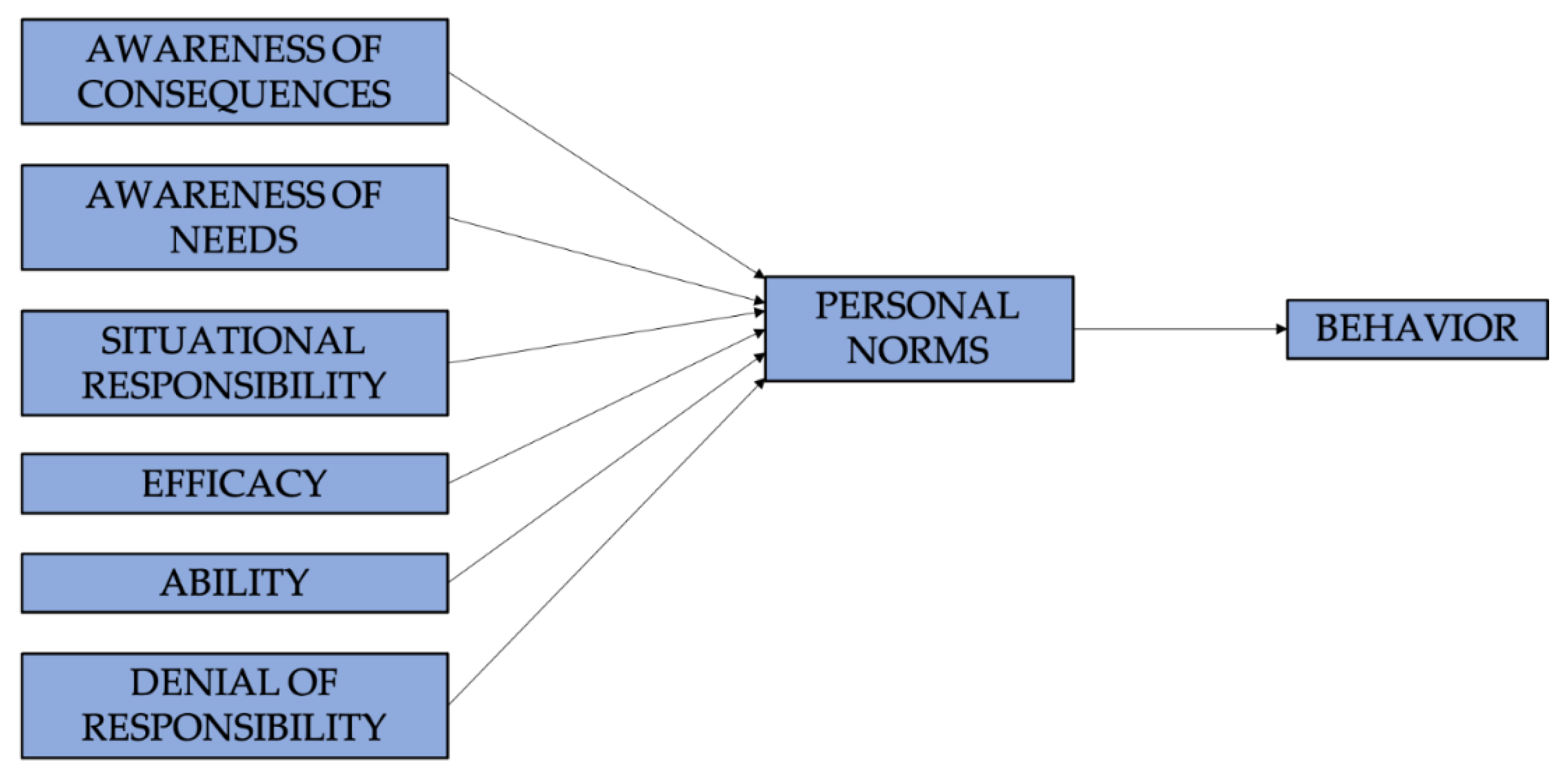

2.2. The Norm Activation Theory

2.3. Network Contact Frequency

2.4. Institutional Trust

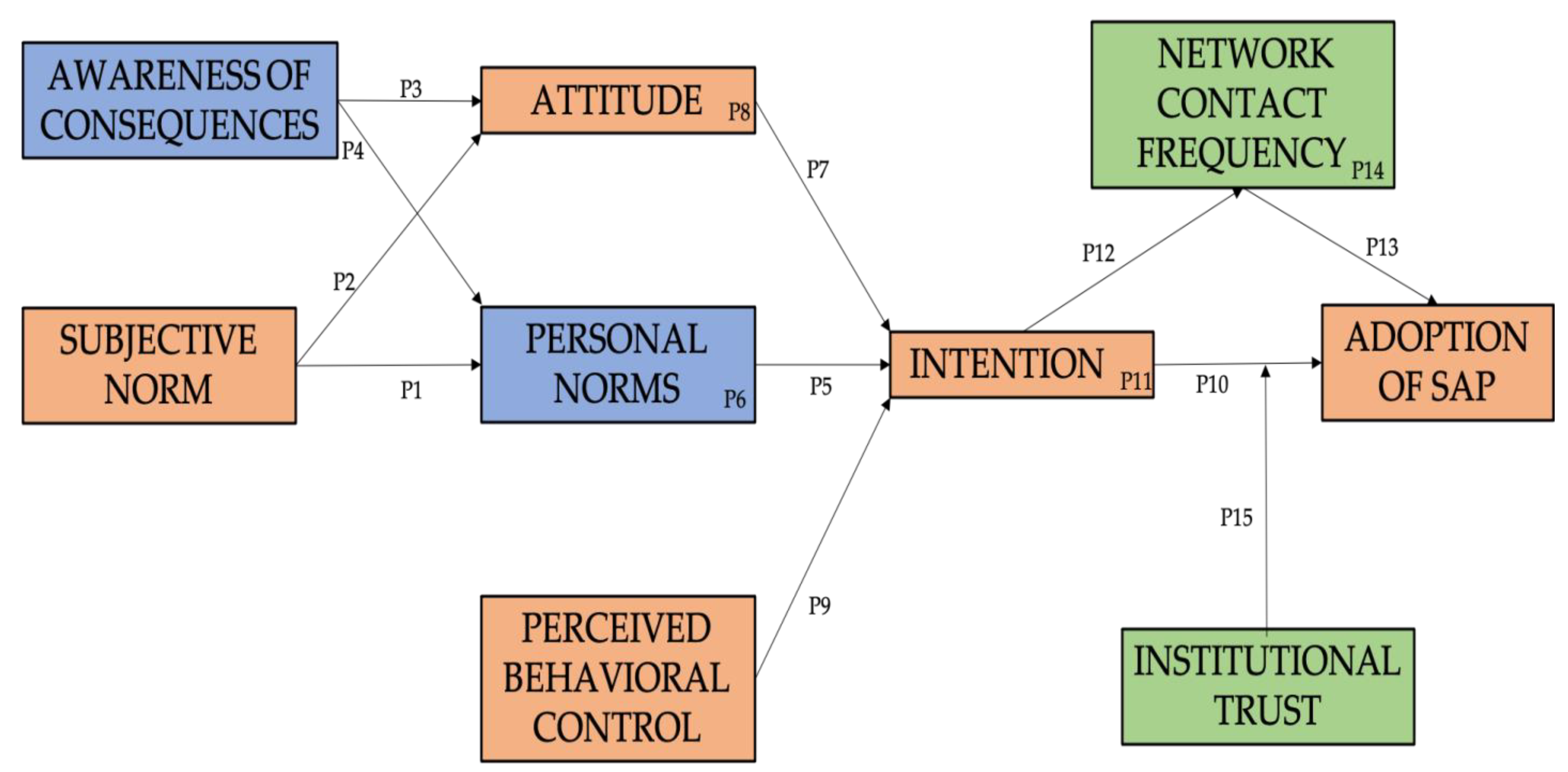

3. Conceptual Framework and Propositions

3.1. Conceptual Framework

3.2. Propositions Development

3.2.1. The Effect of Subjective Norm on Attitude toward SAPs and Personal Ecological Norm

3.2.2. The Effect of Awareness of Consequences on Attitude toward SAPs and Personal Ecological Norm

3.2.3. The effect of Personal Ecological Norm on Intention to Adopt SAPs

3.2.4. The Effect of Attitude toward SAPs on Intention to Adopt SAPs

3.2.5. The Effect of Perceived Behavioral Control on Intention to Adopt SAPs

3.2.6. The Effect of Intention to Adopt SAPs on SAPs Adoption

3.2.7. The Mediation Effect of Network Contact Frequency in the Relationship between Intention to Adopt SAPs and the Adoption of SAPs

3.2.8. The Moderating Effect of Institutional Trust in the Relationship between Intention to Adopt SAPs and the Adoption of SAPs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tilman, D.; Fargione, J.; Wolff, B.; D’Antonio, C.; Dobson, A.; Howarth, R.; Schindler, D.; Schlesinger, W.H.; Simberloff, D.; Swackhamer, D. Forecasting Agriculturally Driven Global Environmental Change. Science 2001, 292, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, M.; Saba, V. Explaining Ocean Warming: Causes, Scale, Effects and Consequences; IUCN: Gland, Switzerlan, 2016; pp. 289–302. [Google Scholar]

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Beddington, J.R.; Crute, I.R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; Muir, J.F.; Pretty, J.; Robinson, S.; Thomas, S.M.; Toulmin, C. Food Security: The Challenge of Feeding 9 Billion People. Science 2010, 327, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.W. Is Agricultural Sustainability a Useful Concept? Agric. Syst. 1996, 50, 117–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacRae, R.J.; Hill, S.B.; Mehuys, G.R.; Henning, J. Farm-Scale Agronomic and Economic Conversion from Conventional to Sustainable Agriculture11Ecological Agriculture Projects Research Paper No. 9. In Advances in Agronomy; Brady, N.C., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; Volume 43, pp. 155–198. ISBN 00652113. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, C.A.; Sander, D.; Martin, A. Search for a Sustainable Agriculture: Reduced Inputs and Increased Profits. Crop. Soils 1987, 39, 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood, R.R. A history of sustainable agriculture. In Sustainable Agricultural Systems; Soil and Water Conservation Society: Ankeny, IA, USA, 1990; pp. 3–19. ISBN 9780935734218. [Google Scholar]

- Brodt, S.; Six, J.; Feenstra, G.; Ingels, C.; Campbell, D. Sustainable Agriculture. Nat. Educ. Knowl. 2011, 3, 1. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, S. FAO, IFAD, and WFP. The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2015: Meeting the 2015 International Hunger Targets: Taking Stock of Uneven Progress. Rome: FAO, 2015. Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 623–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulibaly, P.T.; Du, J.; Dabuo, F.T.; Akouatcha, G.H. The Effect of Farmers Social Networks on Sustainable Agricultural Practices Adoption: A Scoping Review Protocol. Int. J. Sustain. Agric. Res. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, T.Q.; Rañola, R.F.; Camacho, L.D.; Simelton, E. Determinants of Farmers’ Adaptation to Climate Change in Agricultural Production in the Central Region of Vietnam. Land Use Policy 2018, 70, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borras, S.M.; Franco, J.C.; Suárez, S.M. Land and Food Sovereignty. Third World Q. 2015, 36, 600–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nmadu, J.; Omojeso, B.; Sallawu, H. Socio-economic factors affecting adoption of innovations by cocoa farmers in ondo state, nigeria. Eur. J. Bus. Econ. Account. 2015, 3, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Ng’ombe, J.; Kalinda, T.; Tembo, G.; Kuntashula, E. Econometric Analysis of the Factors That Affect Adoption of Conservation Farming Practices by Smallholder Farmers in Zambia. J. Sustain. Dev. 2014, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, N. Agent-Based Models; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA; London, UK; New Delhi, India; Singapore, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Teklewold, H.; Kassie, M.; Shiferaw, B.; Köhlin, G. Cropping System Diversification, Conservation Tillage and Modern Seed Adoption in Ethiopia: Impacts on Household Income, Agrochemical Use and Demand for Labor. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 93, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, F.J.; Barreiro-Hurlé, J.; Van Bavel, R. Behavioural Factors Affecting the Adoption of Sustainable Farming Practices: A Policy-Oriented Review. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2019, 46, 417–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saptutyningsih, E.; Diswandi, D.; Jaung, W. Does Social Capital Matter in Climate Change Adaptation? A Lesson from Agricultural Sector in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Land Use Policy 2019, 95, 104189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, M.A.; Thapa, G.B. The Effect of Agricultural Extension Services: Date Farmers’ Case in Balochistan, Pakistan. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2018, 17, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damalas, C.; Koutroubas, S. Farmers’ Training on Pesticide Use Is Associated with Elevated Safety Behavior. Toxics 2017, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferroni, M.; Castle, P. Public-Private Partnerships and Sustainable Agricultural Development. Sustainability 2011, 3, 1064–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendran, N.; Tey, Y.S.; Brindal, M.; Sidique, S.; Shamsudin, M.N.; Radam, A.; Abdul Hadi, A.H. Factors Influencing the Adoption of Bundled Sustainable Agricultural Practices: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. Food Res. J. 2016, 23, 2271–2279. [Google Scholar]

- Akintunde, E. Theories and Concepts for Human Behavior in Environmental Preservation. J. Environ. Sci. Public Health 2017, 1, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnton, A. Practical Guide: An Overview of Behaviour Change Models and Their Uses; Government Social Research Unit: London, UK, 2008.

- Jackson, T. Motivating Sustainable Consumption: A Review of Evidence on Consumer Behaviour and Behavioural Change. Sustain. Dev. Res. Netw. 2005, 15, 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Hwang, J.; Lee, M.J.; Kim, J. Word-of-Mouth, Buying, and Sacrifice Intentions for Eco-Cruises: Exploring the Function of Norm Activation and Value-Attitude-Behavior. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H.; Shi, J.-G.; Tang, D.; Wen, S.; Miao, W.; Duan, K. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior in Environmental Science: A Comprehensive Bibliometric Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behaviour: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison Wesley Co.: Boston, MA, USA, 1975; Volume 27. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare, M. Using the theory of planned behavior to determine the condom use behavior among college students. Am. J. Health Stud. 2015, 30, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Perceived Behavioral Control, Self-Efficacy, Locus of Control, and the Theory of Planned Behavior1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Normative Influences on Altruism; Berkowitz, L.B.T.-A., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1977; Volume 10, pp. 221–279. ISBN 00652601. [Google Scholar]

- de Groot, J.; Steg, L. Morality and Prosocial Behavior: The Role of Awareness, Responsibility, and Norms in the Norm Activation Model. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 149, 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paço, A. Prosocial Behavior and Sustainable Development. In Encyclopedia of Sustainability in Higher Education; Leal Filho, W., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1321–1325. ISBN 9783030113520. [Google Scholar]

- Piñeiro, V.; Arias, J.; Dürr, J.; Elverdin, P.; Ibáñez, A.M.; Kinengyere, A.; Opazo, C.M.; Owoo, N.; Page, J.R.; Prager, S.D.; et al. A Scoping Review on Incentives for Adoption of Sustainable Agricultural Practices and Their Outcomes. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jitsanguan, T. Sustainable Agriculture Systems for Small-Scale Farmers in Thailand: Implications for the Environment; Food and Fertilizer Technology Center: Kawana, Japan, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Ha, S. Understanding Consumer Recycling Behavior: Combining the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Norm Activation Model. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2014, 42, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijts, N.M.A.; Molin, E.J.E.; Steg, L. Psychological Factors Influencing Sustainable Energy Technology Acceptance: A Review-Based Comprehensive Framework. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, K.; Sugino, H.; Nomura, H.; Michida, Y. Norms and the Willingness to Pay for Coastal Ecosystem Restoration: A Case of the Tokyo Bay Intertidal Flats. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 169, 106423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harland, P.; Staats, H.; Wilke, H.A.M. Explaining Proenvironmental Intention and Behavior by Personal Norms and the Theory of Planned Behavior1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 29, 2505–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler, H.-P. Learning in Social Networks and Contraceptive Choice. Demography 1997, 34, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palloni, A. Diffusion in Sociological Analysis. In International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Wright, J., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2015; pp. 411–416. ISBN 978-0080970875. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.; Lu, Q.; Capareda, S.C. Social Network and Extension Service in Farmers’ Agricultural Technology Adoption Efficiency. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235927. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.; Fernandez, R.M. Strength Matters: Tie Strength as a Causal Driver of Networks’ Information Benefits. Soc. Sci. Res. 2017, 65, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granovetter, M.S. The Strength of Weak Ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wossen, T.; Berger, T.; Mequaninte, T.; Alamirew, B. Social Network Effects on the Adoption of Sustainable Natural Resource Management Practices in Ethiopia. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2013, 20, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, A. The Influence of Social Networks on Agricultural Technology Adoption. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 79, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todo, Y.; Matous, P.; Mojo, D. Effects of Social Network Structure on the Diffusion and Adoption of Agricultural Technology: Evidence from Rural Ethiopia. SSRN 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joffre, O.M.; De Vries, J.R.; Klerkx, L.; Poortvliet, P.M. Why Are Cluster Farmers Adopting More Aquaculture Technologies and Practices? The Role of Trust and Interaction within Shrimp Farmers’ Networks in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Aquaculture 2020, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luhmann, N. Trust and Power Cichester; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.W. Consumer Trust in B2C E-Commerce and the Importance of Social Presence: Experiments in e-Products and e-Services. Omega 2004, 32, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, F.; Nooteboom, B.; Hoogendoorn, A. Actions That Build Interpersonal Trust: A Relational Signalling Perspective. Rev. Soc. Econ. 2010, 68, 285–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PytlikZillig, L.M.; Kimbrough, C.D.; Shockley, E.; Neal, T.M.S.; Herian, M.N.; Hamm, J.A.; Bornstein, B.H.; Tomkins, A.J. A Longitudinal and Experimental Study of the Impact of Knowledge on the Bases of Institutional Trust. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, H.; Marshall, G.A. Trust, Political Orientation, and Environmental Behavior. Environ. Politics 2018, 27, 385–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, S.; Burnett, M.; Hills, P.; Welford, R. Trust, Public Participation and Environmental Governance in Hong Kong. Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camp, W. Formulating and Evaluating Theoretical Frameworks for Career and Technical Education Research. J. Vocat. Educ. Res. 2001, 26, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liehr, P.; Smith, M. Middle Range Theory: Spinning Research and Practice to Create Knowledge for the New Millennium. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 1999, 21, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peshkin, A. The Goodness of Qualitative Research. Educ. Res. 1993, 22, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behaviour: Reactions and Reflections. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumaedi, S.; Yarmen, M.; Bakti, I.G.M.Y.; Rakhmawati, T.; Astrini, N.J.; Widianti, T. The Integrated Model of Theory Planned Behavior, Value, and Image for Explaining Public Transport Passengers’ Intention to Reuse. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2016, 27, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, N.; Hagger, M.; Streukens, S.; Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Claes, N. Testing an Integrated Model of the Theory of Planned Behaviour and Self-Determination Theory for Different Energy Balance-Related Behaviours and Intervention Intensities. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 113–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Sheng, H.; Mundorf, N.; Redding, C.; Ye, Y. Integrating Norm Activation Model and Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand Sustainable Transport Behavior: Evidence from China. Int J. Env. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setiawan, B.; Afiff, A.Z.; Heruwasto, I. Integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior With Norm Activation in a Pro-Environmental Context. Soc. Mark. Q. 2020, 26, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, R.; Safa, L.; Damalas, C.A.; Ganjkhanloo, M.M. Drivers of Farmers’ Intention to Use Integrated Pest Management: Integrating Theory of Planned Behavior and Norm Activation Model. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 236, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Möser, G. Twenty Years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A New Meta-Analysis of Psycho-Social Determinants of pro-Environmental Behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanpanah, M.; Forouzani, M. Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Predict Iranian Students’ Intention to Purchase Organic Food. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.Y.N. The Moderating Role of Trust and the Theory of Reasoned Action. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 1221–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Seock, Y.-K. The Roles of Values and Social Norm on Personal Norms and Pro-Environmentally Friendly Apparel Product Purchasing Behavior: The Mediating Role of Personal Norms. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 51, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. Norms for Environmentally Responsible Behaviour: An Extended Taxonomy. J. Environ. Psychol. 2006, 26, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Geng, G.; Sun, P. Determinants and Implications of Citizens’ Environmental Complaint in China: Integrating Theory of Planned Behavior and Norm Activation Model. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 166, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Rees, J. Environmental Attitudes and Behavior: Measurement. In International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 699–705. ISBN 9780080970875. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H. The Norm Activation Model and Theory-Broadening: Individuals’ Decision-Making on Environmentally-Responsible Convention Attendance. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Ostrom, E.; Tesfatsion, L.; Judd, K. Governing Social-Ecological Systems. Handbook of Computational Economics II: Agent-Based Computational Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nordlund, A.; Garvill, J. Effects of Values, Problem Awareness, and Personal Norm on Willingness to Reduce Personal Car Use. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Hunecke, M.; Blöbaum, A. Social Context, Personal Norms and the Use of Public Transportation: Two Field Studies. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J.; Ölander, F. The Dynamic Interaction of Personal Norms and Environment-Friendly Buying Behavior: A Panel Study1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 36, 1758–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, S.; Hussin, A.R.C.; Dahlan, H.M.; Yadegaridehkordi, E. Theoretical Model for Green Information Technology Adoption. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2015, 10, 17720–17729. [Google Scholar]

- Mastrangelo, M.; Gavin, M.; Laterra, P.; Linklater, W.; Milfont, T. Psycho-Social Factors Influencing Forest Conservation Intentions on the Agricultural Frontier. Conserv. Lett. 2013, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlett, C.P. Social Psychology Theory Extensions; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; Chapter 5; pp. 37–47. ISBN 9780128166536. [Google Scholar]

- Mafabi, S.; Nasiima, S.; Muhimbise, E.M.; Kasekende, F.; Nakiyonga, C. The Mediation Role of Intention in Knowledge Sharing Behavior. Vine J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2017, 47, 172–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Octav-Ionut, M. Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior in Predicting Pro- Environmental Behaviour: The Case of Energy Conservation. Acta Univ. Danub. Œcon. 2015, 11, 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Dalvi Esfahani, M.; Nilashi, M.; Rahman, A.A.; Ghapanchi, A.H.; Zakaria, N.H. Psychological Factors Influencing the Managers’ Intention to Adopt Green IS: A Review-Based Comprehensive Framework and Ranking the Factors. Int. J. Strateg. Decis. Sci. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhang, L.; Hu, Q.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, W. Understanding Chinese Residents’ Waste Classification from a Perspective of Intention–Behavior Gap. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepic, M.; Trienekens, J.; Hoste, R.; Omta, O. The Influence of Networking and Absorptive Capacity on the Innovativeness of Farmers in the Dutch Pork Sector. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2012, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Reagans, R.; McEvily, B. Network Structure and Knowledge Transfer: The Effects of Cohesion and Range. Adm. Sci. Q. 2003, 48, 240–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carley, K. Knowledge Acquisition as a Social Phenomenon. Instr. Sci. 1986, 14, 381–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcknight, D.; Chervany, N. Trust and Distrust Definitions: One Bite at a Time. In Trust in Cyber-Societies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; Volume 2246, pp. 27–54. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.; James, H.S. Organizational Trust in Farmer Organizations: Evidence from the Chinese Fresh Apple Industry. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 676–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.; Bhatti, A.; Mohamed, R.; Ayoup, H. The Moderating Role of Trust and Commitment between Consumer Purchase Intention and Online Shopping Behavior in the Context of Pakistan. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.-G.; Jeong, S.; Choi, Y. Moderating Effects of Trust on Environmentally Significant Behavior in Korea. Sustainability 2017, 9, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pierrette Coulibaly, T.; Du, J.; Diakité, D.; Abban, O.J.; Kouakou, E. A Proposed Conceptual Framework on the Adoption of Sustainable Agricultural Practices: The Role of Network Contact Frequency and Institutional Trust. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042206

Pierrette Coulibaly T, Du J, Diakité D, Abban OJ, Kouakou E. A Proposed Conceptual Framework on the Adoption of Sustainable Agricultural Practices: The Role of Network Contact Frequency and Institutional Trust. Sustainability. 2021; 13(4):2206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042206

Chicago/Turabian StylePierrette Coulibaly, Tiéfigué, Jianguo Du, Daniel Diakité, Olivier Joseph Abban, and Elvis Kouakou. 2021. "A Proposed Conceptual Framework on the Adoption of Sustainable Agricultural Practices: The Role of Network Contact Frequency and Institutional Trust" Sustainability 13, no. 4: 2206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042206

APA StylePierrette Coulibaly, T., Du, J., Diakité, D., Abban, O. J., & Kouakou, E. (2021). A Proposed Conceptual Framework on the Adoption of Sustainable Agricultural Practices: The Role of Network Contact Frequency and Institutional Trust. Sustainability, 13(4), 2206. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042206