Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic offers youth sport organizations the opportunity to anticipate consumer behaviour trends and proactively improve their program offerings for more satisfying experiences for consumers post-pandemic. This conceptual paper explores potential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on changing youth sport and physical activity preferences and trends to inform sport and physical activity providers. Drawing from social ecology theory, assumptions for future trends for youth sport and physical activity are presented. Three trends for youth sport and physical activity as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic are predicted: (1) youths’ preferences from organized to non-organized contexts become amplified; (2) reasons for participating in sport or any physical activity shift for youth as well as parents/guardians; (3) consumers reconceptualize value expectations from youth sport and physical activity organizations. The proposed assumptions need to be tested in future research. It is anticipated that sport organizations can respond to changing trends and preferences by innovating in three areas: (1) programming, (2) marketing, and (3) resource management.

1. Introduction

Youth sport and physical activity preferences and trends are constantly shifting. The contemporary trends demonstrated by youth participants prior to the COVID-19 pandemic include a gradual shift in preferences from organized (e.g., club or team) to non-organized (e.g., informal pickup participation or spontaneous play) settings [1] and from traditional, mainstream sports (e.g., baseball or hockey) to non-traditional, new, or unique sports (e.g., rock climbing or skateboarding) [2]. These trends indicate that although participation in traditional and organized sport is still prevalent, participants are also taking up or switching to these non-traditional sports in non-organized settings to challenge formal practices and have less rule-bound experiences [1,2,3,4]. As such, in western nations, namely Canada, tensions have emerged with organized sport clubs, because funding and access to resources is typically tied to registration numbers [1,5].

Tensions have emerged because of funding, but from two different angles. First, when traditional sports are practiced in non-organized settings, clubs tend to try to intervene to encourage club participation to increase their membership and thus their funding [1,5]. Second, when non-traditional sports emerge, there is typically no governing body in the traditional sense or formal club settings [5]; in order to access resources in western contexts, these non-traditional sports might be forced to become more professionalized and formalized [1,2,3,4], as seen with skateboarding in Scotland [2] and parkour in the United Kingdom [6]. Indeed, rather than adapt to consumers’ changing expectations, sport providers have typically attempted to formalize these new sports and fit them into existing forms of programming provision [1,2,3,4].

Interestingly, while these shifts in youths’ preferences for sport and physical activity have been occurring, participation rates seem to be declining in organized sport among youth in western countries [7,8]. A report by a Canadian non-profit organization found that although most Canadian youth do in fact participate in sport, the amount of sport and physical activity practiced is not enough to meet daily physical activity requirements [9]. Specifically, parents of five to 11 year old children reported that their children participate in an average of 17 min of organized sport per day, while youth aged 12–15 reported participating in an average of 34 min per day in sport in an organized or unorganized setting [9].

Trends present within youth sport and physical activity practices express consumers’ behaviors and preferences of youth sport and physical activity, which have important implication for sport and physical activity providers. As youth drop out of organized sport as they age [10,11,12], and in alignment with current participation trends of unorganized participation [1], youth might continue to practice sport, but simply in an unorganized fashion. Perhaps this decline in organized sport is not a coincidence at all, but rather a product of a lack of understanding of and inability to satisfy youth sport and physical activity consumers’ expectations from their experiences. Thus, sport organizations must continually re-evaluate the ability of program offerings to meet the everchanging preferences and expectations of sport and physical activity consumers.

The forced pause caused by COVID-19 provided sport organizations with opportunities to reflect on youths’ sport and physical activity past experiences and future needs, allowing sport organizations to adapt programming to accommodate reshaped preferences [13], thus improving and sustaining recovery efforts. Therefore, the purpose of this conceptual paper is to explore potential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on changing youth sport and physical activity preferences and trends to inform sport and physical activity providers. Using social ecology theory, potential shifts in future youth sport participation trends will be explored for a post-pandemic world. The paper will conclude with possible implications of these future trends for sport management practitioners and provide recommendations for future research.

COVID-19 and Youth Sport and Physical Activity Participation

A substantial global event that has affected youth sport and physical activity and beyond is the COVID-19 pandemic, a novel strain of the coronavirus, that began to affect youth sport and physical activity in early 2020. Though the pandemic has been devastating for many industries globally, it also has presented major challenges for the survival of sport organizations. However, the pandemic has not only forced sport organizations, but also consumers, including parents and guardians, to think of youth sport and physical activity participation in new and different ways [14,15], thus potentially modifying sport habits of youth. These implications of the pandemic for youth sport and physical activity are further discussed below.

To help stop the spread of the virus in Canada and many other nations, traditional structures and opportunities for youth sport participation of which consumers were accustomed were simply not available during the pandemic [16,17]. Youth sport participation and physical activity had to quickly adapt in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, exposing youth to different forms of sport and physical activity [14,15,18]. These changes in opportunities for youth sport and physical activity participation could have led some youth to (1) try a different form of their favourite sports, (2) try a new sport (in an online organized or non-organized context), (3) take up sport and physical activity, or (4) stop participating in sport and physical activity altogether. As youth sport and physical activity practices were forced to shift in the context of a pandemic, it could be reasonably assumed that expectations for future participation did also. It is unknown, however, if and how these expectations have changed. Thus, the pandemic can inform if and how youth sport and physical activity preferences have shifted (or not).

Moreover, as in-person youth sport programming resumes, organizations have had to, and will have to continue to, modify their practices to adhere to public health guidelines [13,14,19]. This stall in service provision and acknowledgment that programming will need to be different in the near future [13] act as a forced pause for reflection on youth sport and physical activity programming, serving as an opportunity for youth sport providers to conduct a comprehensive evaluation to satisfy their consumers’ needs. Indeed, youth sport providers will have to adapt programming in repose to the pandemic. However, organizations can go further to understand their consumers’ already changing expectations of programming more broadly, and adapt where necessary to return from the pandemic with stronger programs that better satisfy consumers. The COVID-19 pandemic provides organizations with the opportunity to re-evaluate what value their consumers are seeking from youth sport and physical activity experiences and make adjustments to their programming to offer more satisfying experiences.

In recent months, several studies and academic commentaries have emerged addressing the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on sport. Several of these works have addressed the implications for professional sport and major sport events [20,21,22,23,24]—fittingly, as the major global entertainment sector was at the forefront of media coverage. An emerging line of academic work is beginning to consider the implications of the pandemic for youth and community sport. These works have covered several aspects of the community sport sector, including sport development systems [17], community sport organization structures [16], and community sport for persons with disabilities [18]. These investigations and commentaries have provided important insights into the immediate, short term [16,18], and long term [17] implications for community sport systems and structures. An important aspect of community sport that has yet to be considered in the COVID-19 response literature is shifting patterns and preferences of youth sport consumers. Sport organizations need to know what their consumers will want for both return to sport and long-term sport provision in order to effectively adapt. Thus, understanding how the pandemic has affected consumers preferences toward sport and physical activity and associated trends is important in understanding the long-term implications for community sport organizations. Indeed, rather than examining the health implications of returning to sport and accommodating for COVID-19 within the existing youth sport structures, this paper explores potential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on changing youth sport and physical activity preferences and trends to inform sport and physical activity providers. Through identifying the value perceived to be important by youth sport and physical activity consumers, youth sport providers will be able to offer new value propositions to attract and retain participants.

2. Youth Sport and Physical Activity Consumption

There are two primary purposes for consumption; autotelic actions, or when the consumer engages in an activity as an end in itself; and instrumental, meaning that the purpose of consumption is as a means to a further end [25]. In the context of youth sport and physical activity participation, two consumers groups can be distinguished: (1) the youth participants themselves, who consume mainly for autotelic reasons, and (2) parent(s)/guardians, who stimulate their children to consume sport predominantly for instrumental reasons (Holt, 1995). Consumers engage in autotelic actions for the sake of the activity [26]. Many youths consume sport and physical activity for autotelic purposes; they participate for a fun experience [12,27,28,29,30]. For instance, when investigating factors that influence adolescent girls’ sport and physical activity behaviours in Australia, Casey and colleagues [27] found that fun activities and being with friends were two of the strongest reasons for participation in sport and physical activity. When looking at youth aged 12–18 of both genders in Ireland, Tannehill and colleagues [12] also found that youth participate in sport primarily for fun and to be with friends. In a study of youth in the United States participating in a track program, Sirard and colleagues [31] found that girls participated in sport for mainly social benefits, but also competition and fitness, whereas boys participated mainly for competition, but also for socializing and fitness. Moreover, adolescent girls specifically expected to participate in sport in a welcoming and supportive environment [32] and to receive support from their peers, their family, and their coach [27,29]. These findings indicate that youth who exhibit different characteristics will hold different expectations for their sport and physical activity experiences.

Many parents and guardians stimulate their children to consume sport and physical activities for instrumental purposes, often seeking developmental outcomes for their children that are claimed to be associated with sport and physical activity (e.g., socialization, physical competency, strong character) [28,30]. Parents also expect that their children will have fun and socialize; however, they tend to place stronger expectations on developmental outcomes such as building good character [30], teamwork skills [28,30], and personal skills (e.g., emotional control, discipline, confidence) [28]. Moreover, parents tend to be more critical of their children’s organized sport experiences than the children themselves [30]. For example, when reporting perceptions of outcomes of a youth football program in the United States, youth rated perceptions of all measured outcomes higher than their parents’ reported perceptions [30].

Satisfying Experiences

Regardless of purpose of consumption, consumers’ experiences with youth sport and physical activity are a central element of evaluation of their engagement with the program offering [33]. Marketers strive to create satisfying overall consumer experiences; however, what is considered to be satisfying is subjective, and is entirely dependent upon the perception of each individual consumer. A common way to conceptualize satisfaction is the disconfirmation paradigm: consumers have a set of expectations prior to an experience, and if the experience meets or exceeds the expectations, the consumer is satisfied; if the experience does not meet expectation, consumers are dissatisfied [34,35]. Thus, consumer satisfaction is achieved when experience providers equal or exceed consumers’ expectations [35,36]. Therefore, to achieve satisfying consumer experiences, experience providers must understand consumers’ expectations.

Expectations are also determined by each individual [34], meaning that the objective service offered has little to do with customer satisfaction; rather, the consumer’s lived experience with the service is how satisfaction is derived [35]. A common expectation of consumers is that they will receive value from their experience [37]. Experience providers offer value propositions, and consumers interpret and evaluate these value propositions during the consumption experience [37,38]. Experience providers can create conditions under which consumers might be more likely to go through a satisfactory experience, but it is ultimately up to the consumer to decide if value was in fact received [37].

The collaboration between the experience provider and the consumer indicates that value is co-created between the providers and participants; it is the interaction between the resources offered by the provider and then consumed by the consumer [39]. These recourses can be divided into two categories: operand and operant [37,38,39]. Operand resources are physical resources [38] such as equipment and facilities for youth sport and physical activity. Operant resources, on the other hand, are human, organizational, informational, and relational resources [38], such as scheduling, training, and league structures found in youth sport. Youth sport providers create a value proposition (i.e., what they offer that no one else does) and the youth and the parents evaluate their experiences to determine if the value proposition had led to valuable experiences (i.e., satisfactory experiences).

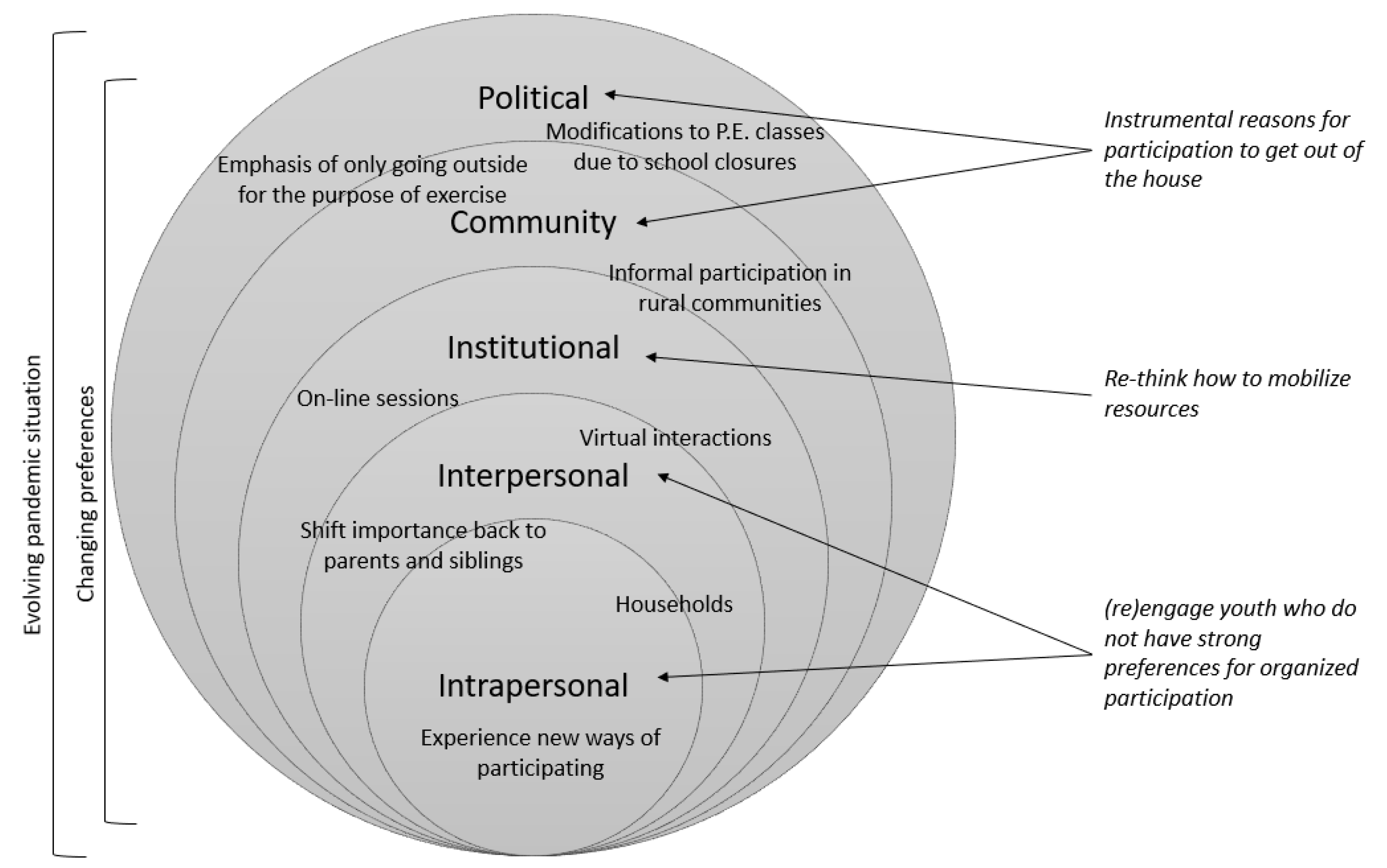

Indeed, this individually interpreted conceptualization of satisfaction and value is in alignment with an interpretivist paradigm. Interpretivism is centred around the philosophical belief that reality and meaning of the social world are interpreted by individuals based on culturally and historically situated meanings [40]. This means that each individual has their own evaluation of reality and the world around them that is also shaped by their environment and surroundings [40]. In alignment with this view of understanding reality is social ecology theory. a theory that is centred around the individual and how their behaviour is shaped by their interaction with the social and built environment. Clearly, COVID-19 has generated a major shock in the environment, thereby affecting each individual in society. Hence, social ecology theory and the associated model are helpful in understanding how this new reality affects youth sport consumer behaviour. As seen in Figure 1, the socioecological environment is comprised of five levels of interaction with the individual (i.e., intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, community, political), all of which are important in shaping the individual [41,42].

Figure 1.

Social ecology theory and assumed implications of COVID-19 for youth sport and physical activity.

3. Social Ecology Theory

Social ecology theory is a theory that is often leveraged in sport studies, as it aids researchers in understanding the role of both the social and built environment in individuals’ lives [41,43] with regards to sport and physical activity [28]. The theory has been used to understand youth sport and physical activity in many contexts including rural adolescent participation preferences [27], low-income families’ sport and physical activity participation [28], physical education [44], participation context (e.g., clubs, public spaces) [45,46], and to identify predictors of sport and physical activity [47].

Social ecology theory is also often used to guide the planning, implementation, and evaluation of interventions designed to impact youth sport participation [48,49,50]. The COVID-19 pandemic, although not planned, has acted as an intervention for youth sport participation by changing the way youth were exposed to and able to practice sport and physical activity. Ultimately, the restrictions imposed upon youth and their families changed youths’ routines and possibly how they conceptualized sport and physical activity. The possible exposure to new forms of sport and physical activity carried the potential to (re)shape what youth sport and physical activity consumers considered to be a satisfying experience. Based on current knowledge of the antecedents of youth sport and physical activity, the following sections describe how the COVID-19 pandemic are expected to have impacted or amplify (or continue to impact or amplify) youth sport participation and physical activity using social ecology theory as a framework (or lens). These possible impacts are also depicted in Figure 1.

3.1. Intrapersonal Factors

Intrapersonal factors include states that originate within the individual, such as youths’ preferences and past experiences with sport [41,51]. Youths’ past experience with sport and physical activity predict future preferences and practices [52,53]. As stated above, the limitations on the activities available to youth during the COVID-19 pandemic could have exposed youth to new and creative ways of participating in sport and physical activities, thus shaping new preferences. Moreover, due to the increased risk of transmission of infectious diseases during contact sports [54], a reasonable shift in participation could be away from contact sports to non-contact sports during the pandemic. The exposure to different types of non-contact sports for youth who might have previously only played contact sports could shape post-pandemic preferences to be geared toward the new non-contact sports they tried during the pandemic.

Another important intrapersonal factor to youth sport and physical activity is interest in participating; a lack of interest in particular activities is an important factor to youth sport drop out [31]. Moreover, although youth might have an interest in participating in sport and physical activity, a preference for competing activities might lead to non-participation in sport [10,11,31]. Several studies have found that youth drop out of sport in favour of other leisure activities, and to prioritize school and studying [10,11,12]. Tannehill and colleagues [12] also found that as youth age and start to understand their own preferences, they might switch from sports to other activities such as debate or music. As many activities were limited during the COVID-19 pandemic, time pressures of older youth could have been eased, possibly allowing for more time to be allocated to sport and physical activity, particularly in the unorganized context.

Finally, physical literacy is the ability to recognize the importance of being physically active, and the ability to adapt physical activity to one’s surroundings [55]. Thus, physical literacy could have been an important contributor to youth sport and physical activity [56] during the pandemic. In an increasingly changing and uncertain time of a pandemic, youth with high physical literacy could have been able to understand the importance of sport and physical activity to overall health, and would have remained active though adapting sport and physical activity practices to their current environment. We recognize, however, that this might be influenced by significant others, such as parents and/or peers—which brings us to the interpersonal level.

3.2. Interpersonal Factors

Interpersonal networks encompass factors related to immediate interactions with others that the individual experiences (i.e., parents, friends) [41,51]. Parents are important role models for youth sport and physical activity habits (i.e., if parents are active, youth are more likely to be active compare to children with non-active parents) [11,52,53,57,58]. Although parents play a significant role in shaping their children’s sport and physical activity lifestyles, as youth age, friends start to play a more significant role in shaping sport and physical activity [11,52,57,58]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, governments placed strict physical restrictions, confining youth and families to their homes [9]. As such, youths’ in-person interaction with peers was limited, perhaps shifting the importance back to parents and siblings as role models for youth sport and physical activity, amplifying the significant of the role of the family unit, particularly for older youth [17].

Indeed, parental support and involvement impact youth sport and physical activity in terms of emotional support (e.g., encouragement), financial support (e.g., paying for club participation, necessary equipment), and time support (e.g., transportation to participation facilities) [45,52,57,59]. The recourses required to support youth sport participation have led youth with a higher socioeconomic status to tend to participate in more organized activities, while youth with a lower socioeconomic status tend to participate in a less organized fashion [58]. Parents with a low socioeconomic status might not have financial resources to enroll youth in organized sports, or might not value the time spent playing sports,= when it could be spent on education or work [57]. Perhaps the postponement of regular club activities during the pandemic might have eased financial and time pressures for some families, leveling the playing field by allowing lower income families to be equally active as higher income families, likely in an unorganized context.

3.3. Institutional Factors

Institutional factors describe the institutions with organizational characteristics that affect the individual, such as offerings at the local community centre or community sport clubs in a region [41,51,53]. These factors consist of the presence or lack of programming in appropriate facilities. Specifically, the availability of sport clubs that offer different sports, as well as the programming schedule determine the opportunities that are available to youth for organized sport [45,47]. Moreover, the financial and schedule demands of sport clubs can put pressure on families [47], determining the feasibility of participation. Finally, a positive and supportive club culture can attract families to participate, while an overly competitive and negative club culture might detract families from participating [27]. Of course, during the COVID-19 pandemic, regular club participation was limited, as no in-person participation was permitted during lockdown, and physical-distancing was required during outside of lockdown periods, though some clubs offered on-line sessions [14,15]. The postponement of regular club activity might have eased financial and time pressures for some families, and alternative participation opportunities could have made sport and physical activity more accessible [18].

3.4. Community Factors

Community factors, such as interactions among networks, describe broader informal networks, such as the accessibility of space and facilities for participating in sport [41,51]. Youths’ access to facilities and ability to spend time outdoors are strong correlates of sport and physical activity [12,52]. Research has shown that urban communities have more facilities and thus sport club offerings than their rural counterparts [27,60]. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, youth in urban communities had more opportunities for sport and physical activity; however, during the pandemic, youth in these urban communities were not allowed to use these facilities or participate in their clubs. Though there are less facilities and clubs in rural communities, there are more open spaces, and thus it could be expected that youth in rural communities had more opportunities for informal participation than their urban counterparts. Indeed, the open spaces would have been available prior to the pandemic; however, the urban–rural participation disparity might have shifted during the pandemic.

3.5. Political Factors

Political factors are the laws and policies at the local, provincial, and national levels, such a sport club requirements and structures [41,51]. For instance, the physical education curriculum in schools can expose youth to certain sports and not others. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many institutions including schools were closed [61], removing traditional physical education classes from youths’ routines. Moreover, the restrictions put into place to help slow the spread of the virus limited the opportunities for families to practice sport and physical activity. Finally, in the early weeks of the pandemic, political figures urged citizens to stay indoors, with the exception of going outside for the purpose of exercise. This constant reminder of the necessity of physical activity, and one of the few reasons permitting individuals to leave their homes, could have played a role in encouraging participants to find other means of sport and physical activity and non-participants to take up sport and physical activity.

3.6. Social Ecology Systems

A critique of social ecology theory is that many of its applications have focused on the interactions within levels of society, generally neglecting the relationships between levels [28,44,46,62]. Thus, it is important to also consider the nested structure of the socioecological environment that interacts within and among various environmental systems [43]. These systems are embedded within each other, and help explain the interaction among social levels [43].

At the most individual-specific level, microsystems describe the face-to-face interactions of individuals. These systems are the immediate environments of the individual, such as family and school peers [43]. Microsystems are nested within mesosystems. Mesosystems describe the links between individuals’ immediate environments [43]. For instance, the relationship between family and school. While mesosystems describe relationship between microsystems that directly influence the individual, exosystems describe the relationship between microsystems that indirectly influence the individual [43]. For example, for youth, the relationship between home and their parent’s workplace. Mesosystems and exosystems are embedded within larger macrosystems. Macrosystems are the overarching societal values and norms that are pervasive among all levels [43]. Finally, chronosystems describe changes over time, in both the development of the individual, and evolution of the environment [43].

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, the microsystems placed an emphasis on the interaction among the family unit [17]. As restrictions were placed on social interactions outside of the household, microsystems between youth and their peers outside of their household were limited. Though mesosystems were also limited, youth could still virtually interact with their school or sport club groups [17,18]. Exosystems, however, encompass the relationship between parent’s responsibilities and youth sport and physical activity. For instance, parents balanced their own work, household chores, supplementing their children’s education, and their own physical activity and/or leisure practices [17]. It is reasonable to expect that all of these experiences of parents had an influence on youth sport and psychical activity practices. Macrosystems describe the overall changing preferences among youth for sport and physical activity. These include the long-term changes in preferences for specific activities or how activities were practiced as a result of the new or different forms of activity afforded by the COVID-19 restrictions. These macrosystems could also include the symbolic value of sport present in a society. In the Canadian context, sport plays an important role in forming youths’ identities [63]. Finally, chronosystems encompass the evolving pandemic situation, along with the easing and tightening of restrictions as the waves of the virus come and go and the gradual return to sport and physical activity.

4. Youth Sport and Physical Activity Trends in a Post-COVID World

Significant sociopolitical events shape preferences [64,65] and can be the root cause of associated major shifts in trends [63,64,65,66]. To our knowledge, investigations on the effects of previous global health crises (e.g., the Spanish flu outbreak of the early 20th century) on sport and physical activity participation trends do not exist. We can, however, draw from past global social events to look at the ability of global events to impact sport and physical activity consumer behaviour. Past major global social events have been associated with a shift in trends for leisure choices (including sport and physical activity). For instance, the industrial revolution brought with it a demand for higher pay and fewer work hours, freeing up money and time for leisure pursuits for the relative masses [67], reshaping leisure trends in Western contexts. Another example is the fact that the millennial generation are tech-savvy young adults due to the rapid development in technology during their formative years. Indeed, the major historical event of the COVID-19 pandemic will influence all those who have experienced it, in several aspects of their life, including their sport and physical activity preferences. Drawing from the discussion above of youth sport and physical activity participation at the socioecological levels and systems, three broad trends can reasonably be anticipated in a post-COVID world that can inform how youth sport participation will continue to be modified, informing sport organizations how to sustain through their recovery efforts. These predictions appear in italics in Figure 1. First, a continuation and reinforcement of the already shifting trend of youths’ preferences from organized to non-organized contexts can be expected. Second, transformations of the reasons for participating in sport and physical activity (i.e., autotelic and instrumental) for some youth and parents/guardians might be apparent. Third, consumers might reconceptualize value from youth sport and physical activity. These trends will be elaborated upon in the following sections. Implications for practitioners and future research avenues will then be offered. These predictions and recommendations for practitioners are presented in Table 1, in alignment with social ecology theory.

Table 1.

Hypothesized flow of events.

4.1. Amplified Trend toward Non-Organized Sport

Indeed, past experiences with sport and physical activity shape preferences toward future participation practices [52]. As such, we predict that the new forms of sport and psychical activity participation that youth were exposed to during the pandemic might impact how youth participate in the future. These new ways of participating in sport and physical activity could include modifications to already practiced sport [18] or trying a new sport altogether (e.g., picking up hiking and biking with family members). Regardless of the nature of participation, these modifications have mainly taken place in non-organized contexts [17]. Although the specific ways in which sport and physical activity preferences were impacted are unknown at this stage, it is possible that there will be a stronger preference for sport and physical activity in a non-organized setting, impacting the overall youth sport development trajectory [17].

Of course, some youth would be itching to get back to their organized teams and leagues; however, this non-organized exposure could help (re)engage youth who did not have strong preferences for organized participation, because of the increased opportunities to try sport and physical activity in a more non-organized fashion during the pandemic. These youth might have realized that they preferred the unstructured setting. Moreover, the pandemic brought more free time for youth with the cancellation of most organized activities, not just sport. As a significant reason for drop-out of sport is competing activities for youths’ time [10,11,31]; the pandemic might have afforded former sport participants the opportunity to re-engage with sport and physical activity. As the only participation option during the pandemic for youth who were not already enrolled in organized programming would have been non-organized settings, this less structured way of participating might help encourage participants to continue their participation post-pandemic in non-organized settings.

4.2. Shift in Participation Purposes

We predict that there might be shifts in reasons for participating in sport and physical activity among youth. In alignment with the trend outlined above, some youth who have been part of organized sports might prefer the non-organized settings and continue their non-organized participation for purely autotelic reasons; they want to participate in sport and physical activity in an informal fashion for the sake of the activity itself [26]. Some youth might also continue to participate in organized sports for autotelic reasons as well, while others might have taken up sport and physical activity altogether during the pandemic. Indeed, as one of the few reasons youth were permitted to leave their house was for exercise, some youth might have tried a new form of sport and physical activity, or even started participating altogether for the instrumental purpose [25] of getting outside. Some of these youth might continue to participate for the instrumental purposes of health, while some might have discovered a new favourite sport or realized they enjoyed being active and continue participation for autotelic purposes.

The interesting aspect of this trend will be among parents and guardians. As previous research indicates, parents tend to enroll their children in organized sport for instrumental purposes (i.e., skill building and development) [28]. The reasons for parents to encourage their children to participate in sport and physical activity during the pandemic in non-organized settings could have also been for developmental purposes, but they could have also shifted for health benefits and to provide their children with something to do. These shifts in instrumental proposes for engaging in youth sport and physical activity would have shifted from largely skill development to broader health reasons, perhaps lifting some of the performance expectations of parents, and thus perhaps helping to mitigate sport dropout [45,52,57,59].

4.3. Reconceptualization of Value

After experiencing new forms of sport and physical activity participation, consumers of youth sport and physical activity will have new ways of understanding how these experiences can be provided. Through experiencing different ways of participating, we predict that youth sport and physical activity consumers might form new expectations of organized sport opportunities, thus rethinking the value that is derived from youth sport and physical activity experiences. For example, the value placed on competing in out-of-town tournaments might have been perceived to be of high value before the pandemic for youth, but after the pandemic, these activities might not be perceived as important to the overall sport experience. Resources held by sport organizations had been mobilized in particular ways prior to the pandemic to provide value to consumers (i.e., operant and operand as described above) [37,38,39]. Consumers of youth sport and physical activity had interpreted value from these resources. As new ways of participating became known to consumers, perhaps the value placed on these resources have shifted. For example, experiencing the unorganized nature of sport and physical activity during the pandemic might have become more valuable to youth, and thus they will seek participation opportunities that incorporate less formal programming. These shifts in conceptualization of value could lead to organizations rethinking how resources are mobilized to provide value to their consumers, and thus satisfying experiences.

4.4. Implications for Sport Organizations

For sport organizations to not only recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, but also become stronger sport providers, proactive actions must be taken to understand how the pandemic might have affected youth sport and physical activity consumer behaviour. Drawing from the predicted trends presented above, sport organizations can take on innovative practices [16] to respond to these trends in three ways: innovative programming; innovative marketing; and innovative resource management.

Sport organizations can continue to be innovative with their programming modifications. Just as programming had been forced to be modified during and immediately post-pandemic, sport organizations can continue to adapt programming to meet evolving preferences of consumers. We predict that more sport and physical activity participants will prefer less organized structures in a post-pandemic world. This is an important trend for community sport organizations to consider, as youth sport development pathways require some sort of structured setting [17]. To help attract these participants to a club setting, sport organizations can offer programming that is less structured, and non-league centred. For example, drop-in programming can be provided, allowing participants to participate within their preference for a less rule-bound experience. Another type of programming that might satisfy those who prefer informal sport would be more introductory programming that does not place an emphasis on competing. Indeed, this type of programming is already common among younger age groups [68]; however, it is less common for older ages. A less competition based option for older age groups could help attract the youth who began participating after a lapse, or started participating altogether during the pandemic.

As the reasons for participating shift, organizations will need to understand why their consumers, and potential consumers, will be looking to participate or enroll their children in organized sport. By understanding why consumers consume, sport organizations will be able to modify and update their marketing practices to develop more effective promotion and recruitment initiatives [25]. Of course, messaging for those participating for autotelic purposes will be different from the techniques used to attract those participating for instrumental purposes. For instance, to attract youth who participate for autotelic purposes, an emphasis on fun and spending time with friends should be highlighted in promotional material [12,27,28,29,30]. On the other hand, consumers who engage for instrumental purposes would be more receptive to messaging that highlights skill development and exercise [28,30]. The implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on marketing practices for youth sport providers might be that current consumers might have shifted their reasons for participating, and non-participants might be interested in participating for somewhat unexpected reasons (e.g., youth for more instrumental reasons, parents for more autotelic reasons). Thus, the ways in which youth sport organizations currently market their programs might have to be re-evaluated and updated to match the shifting preferences of their target market.

Finally, as consumers start to reconceptualize value expected from youth sport and physical activity experiences, sport organizations will have to be innovative with the mobilization [16] of their resources (e.g., operand and operant) [37,38,39]. Indeed, the ways in which sport club resources were mobilized prior to the pandemic might not be perceived as important to families post-pandemic. For example, families might prefer to have some sessions of online programming to help reduce schedule burdens. If that were to be the case, resources would have to be reallocated in the club to be able to offer a combination of in-person and online practices. Sport clubs should consider innovative ways of mobilization their resource to provide offerings that are of value to families based on research evidence.

4.5. Future Research

There remains much to be known about how consumers engaged with youth sport and physical activity during the pandemic, and the subsequent meaning these experiences have for future preferences. As outlined above, meanings that sport and physical activity hold for youth can be vastly different from parents. Moreover, the dynamics of the relationship between youth and parents have been impacted by the pandemic, and have perhaps become even more nuanced and complicated than scholars have established to-date. As such, the consumer preferences related to sport participation and physical activity of each group (i.e., youth and parents) should be considered in future research. Additionally, importantly, the relationship between youth sport participation and physical activity preferences and parents’ preferences for youth sport and physical activity should be explored and unpacked further.

As discussed throughout this commentary, trends in youth sport participation are ever-evolving. Major global phenomena, such as a pandemic, can have an impact on these trends or set new trajectories for sport participation trends [65]. As such, an important line of inquiry for years to come will be to try to fully understand the long-term implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on possible shifts in preferences and subsequent shifts in consumer behaviour of youth sport and physical activity. This line of inquiry should begin by understanding how families adapted their sport and physical activity practices during the pandemic and how those practices might have reshaped their preferences and reasons for participating in the future and their understanding and expectations of value for youth sport and physical activity experiences (if at all).

Finally, as indicated by SET, youth’s environments will determine the types of participation opportunities available, and thus the types of activities participated in [32]. These participation experiences will in turn impact the formation of participation preferences [52]. Particular care should be taken to include the experiences and perspectives from multiple types of consumers: families from different types of communities (e.g., urban, rural); families of varying socioeconomic statuses; those who participated in sport and physical activity before, during, and after the pandemic; and those who took up sport and physical activity for the first time during the pandemic. Indeed, the use of SET in examining the impacts of the pandemic on youth sport and physical activity will provide a comprehensive lens for understanding the complex roles social and built environments for families in their evolving sport and physical activity preferences.

5. Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has important implications for community sport [16,17,18]. Understanding how the pandemic affected participation in sport and physical activity and associated shifts in preferences and consumer behaviour could inform how sport organizations can not only respond to the pandemic, but possibly improve their programming and offerings to better meet consumers expectations, thus sustaining their recovery efforts. This article explored these potential impacts on youth sport and physical activity preferences and trends and offered recommendations for community sport practitioners.

Informed by social ecology theory, the COVID-19 pandemic acted as an unplanned intervention that has affected, and it is expected to continue to shape, youth sport and physical activity preferences and overall trends. Specifically, trends that are reasonable to expect from the COVID-19 pandemic for youth sport and physical activity include (1) an amplified trend of youths’ preferences shifting from organized to non-organized contexts; (2) a transformation in reasons for participating in sport any physical activity; and (3) a reconceptualization of value from youth sport and physical activity. In alignment with Doherty and colleagues [16], sport organizations can respond to these trends by being open to innovative practices, particularly in programming, marketing, and resource management. Specific responses are presently unknown, as specific implications of the pandemic have yet to be fully understood. As such, future research should continue to explore the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in community sport, particularly on youth sport consumer behaviour. From a theoretical perspective, this paper extends the usage of social ecological theory in an unprecedented context of a global pandemic. From a practical standpoint, future research will inform sport clubs’ response to the pandemic in ways that not only help them recover from the pandemic, but also better satisfy consumers. In summary, future lines of inquiry should explore possible shifts in preferences for youth sport and physical activity participation among the youths themselves as well as their parents. Indeed, the global pandemic will leave lasting impacts on many global industries, including sport and physical activity; thus, the long-term impacts of the pandemic on youth sport and physical activity should also be considered in future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: G.T. and M.T.; methodology: G.T.; investigation: G.T. and M.T.; resources: G.T. and M.T.; writing—original draft preparation: G.T.; writing—review and editing: G.T. and M.T.; visualization: G.T. and M.T.; supervision: M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Jeanes, R.; Spaaij, R.; Penney, D.; O’Connor, J. Managing Informal Sport Participation: Tensions and Opportunities. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2019, 11, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D. The Civilized Skateboarder and the Sports Funding Hegemony: A Case Study of Alternative Sport. Sport Soc. 2013, 16, 1248–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, B.; Corte, U. Commercialization and Lifestyle Sport: Lessons from 20 Years of Freestyle BMX in ‘Pro-Town, USA’. Sport Soc. 2010, 13, 1135–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellett, P.; Russell, R. A Comparison between Mainstream and Action Sport Industries in Australia: A Case Study of the Skateboarding Cluster. Sport Manag. Rev. 2009, 12, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, K.; Church, A. Lifestyle Sports Delivery and Sustainability: Clubs, Communities and User-Managers. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2017, 9, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheaton, B.; O’Loughlin, A. Informal Sport, Institutionalisation, and Sport Policy: Challenging the Sportization of Parkour in England. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2017, 9, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, I.E.; O’Reilly, N.; Parent, M.M.; Séguin, B.; Hernandez, T. Determinants of Sport Participation among Canadian Adolescents. Sport Manag. Rev. 2008, 11, 277–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doull, M.; Watson, R.J.; Smith, A.; Homma, Y.; Saewyc, E. Are We Leveling the Playing Field? Trends and Disparities in Sports Participation among Sexual Minority Youth in Canada. J. Sport Health Sci. 2018, 7, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ParticipACTION # Family Influence; Canada: ParticipACTION. 2020. Available online: https://participaction.cdn.prismic.io/participaction/f6854240-ef7c-448c-ae5c-5634c41a0170_2020_Report_Card_Children_and_Youth_Full_Report.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Casper, J.M.; Bocarro, J.N.; Kanters, M.A.; Floyd, M.F. “Just Let Me Play!”—Understanding Constraints That Limit Adolescent Sport Participation. J. Phys. Act. Health 2011, 8, S32–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eime, R.M.; Casey, M.M.; Harvey, J.T.; Sawyer, N.A.; Symons, C.M.; Payne, W.R. Socioecological Factors Potentially Associated with Participation in Physical Activity and Sport: A Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Girls. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2015, 18, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannehill, D.; MacPhail, A.; Walsh, J.; Woods, C. What Young People Say about Physical Activity: The Children’s Sport Participation and Physical Activity (CSPPA) Study. Sport Educ. Soc. 2015, 20, 442–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M. Delayed Play: Why Waits Are Expected in Team Sports, Even with COVID Guidelines. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/delayed-sports-guidelines-covid-nl-1.5604965 (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Brady, R. Youth Sports May Look Very Different This Summer—If They Return at All. The Globe and Mail. 20 May 2020. Available online: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/article-youth-sports-may-look-very-different-this-summer-if-they-return-at/ (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Cotnam, H. Amateur Soccer Taking a Kicking from COVID-19. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/covid-turfed-amateur-soccer-season-ottawa-1.5585110 (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Doherty, A.; Millar, P.; Misener, K. Return to Community Sport: Leaning on Evidence in Turbulent Times. Manag. Sport Leis. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, A.L.; Erickson, K.; Turnnidge, J. Youth Sport in the Time of COVID-19: Considerations for Researchers and Practitioners. Manag. Sport Leis. 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, H.; Stride, A.; Drury, S. COVID-19, Lockdown and (Disability) Sport. Manag. Sport Leis. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Considerations for Youth Sports. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/schools-childcare/youth-sports.html (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Hayes, M. Social Media and Inspiring Physical Activity during COVID-19 and Beyond. Manag. Sport Leis. 2020, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsen, J.A.L.; Hayton, J.W. Toward COVID-19 Secure Events: Considerations for Organizing the Safe Resumption of Major Sporting Events. Manag. Sport Leis. 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, M.; Nassis, G.P.; Brito, J.; Randers, M.B.; Castagna, C.; Parnell, D.; Krustrup, P. Return to Elite Football after the COVID-19 Lockdown. Manag. Sport Leis. 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnell, D.; Widdop, P.; Bond, A.; Wilson, R. COVID-19, Networks and Sport. Manag. Sport Leis. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Oshimi, D.; Bizen, Y.; Saito, R. The COVID-19 Outbreak and Public Perceptions of Sport Events in Japan. Manag. Sport Leis. 2020, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, D.B. How Consumers Consume: A Typology of Consumption Practices. J. Consum. Res. 1995, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; ISBN 978-94-017-9087-1. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, M.M.; Eime, R.M.; Payne, W.R.; Harvey, J.T. Using a Socioecological Approach to Examine Participation in Sport and Physical Activity among Rural Adolescent Girls. Qual. Health Res. 2009, 19, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, N.L.; Kingsley, B.C.; Tink, L.N.; Scherer, J. Benefits and Challenges Associated with Sport Participation by Children and Parents from Low-Income Families. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2011, 12, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallinson-Howard, S.H.; Knight, C.J.; Hill, A.P.; Hall, H.K. The 2 × 2 Model of Perfectionism and Youth Sport Participation: A Mixed-Methods Approach. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2018, 36, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, K.A.; Wells, M.S.; Arthur-Banning, S. Experiences in Youth Sports: A Comparison between Players and Parents Perspectives. J. Appl. Sport Manag. Urbana 2010, 2, n/a. [Google Scholar]

- Sirard, J.; Pfeiffer, K.; Pate, R. Motivational Factors Associated with Sports Program Participation in Middle School Students. J. Adolesc. Health 2006, 38, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, M.M.; Eime, R.M.; Harvey, J.T.; Sawyer, N.A.; Craike, M.J.; Symons, C.M.; Payne, W.R. The Influence of a Healthy Welcoming Environment on Participation in Club Sport by Adolescent Girls: A Longitudinal Study. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carù, A.; Cova, B. Revisiting Consumption Experience: A More Humble but Complete View of the Concept. Mark. Theory 2003, 3, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnould, E.J.; Price, L.L. River Magic: Extraordinary Experience and the Extended Service Encounter. J. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H.; Chang, Y.-H.; Fan, F.-C. Adolescents and Leisure Activities: The Impact of Expectation and Experience on Service Satisfaction. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2012, 40, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Keller, K.L. Marketing Management, 13th ed.; Pearson: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. A service-dominant logic for marketing. In The SAGE Handbook of Marketing Theory; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2011; pp. 219–234. ISBN 978-1-84787-505-1. [Google Scholar]

- Edvardsson, B.; Tronvoll, B.; Gruber, T. Expanding Understanding of Service Exchange and Value Co-Creation: A Social Construction Approach. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyrberg Yngfalk, A. ‘It’s Not Us, It’s Them!’—Rethinking Value Co-Creation among Multiple Actors. J. Mark. Manag. 2013, 29, 1163–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotty, M. The Foundations of Social Research; SAGE: Gold Coast, QLD, Australia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Toward an Experimental Ecology of Human Development. Am. Psychol. 1977, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokols, D. Establishing and Maintaining Healthy Environments: Toward a Social Ecology of Health Promotion. Am. Psychol. 1992, 47, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Ecological Models of Human Development. Read. Dev. Child. 1994, 2, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Solmon, M.A. Optimizing the Role of Physical Education in Promoting Physical Activity: A Social-Ecological Approach. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2015, 86, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basterfield, L.; Gardner, L.; Reilly, J.K.; Pearce, M.S.; Parkinson, K.N.; Adamson, A.J.; Reilly, J.J.; Vella, S.A. Can’t Play, Won’t Play: Longitudinal Changes in Perceived Barriers to Participation in Sports Clubs across the Child–Adolescent Transition. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2016, 2, e000079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deelen, I.; Ettema, D.; Kamphuis, C.B.M. Sports Participation in Sport Clubs, Gyms or Public Spaces: How Users of Different Sports Settings Differ in Their Motivations, Goals, and Sports Frequency. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, K.; Ball, K.; Zarnowiecki, D.; Stanley, R.; Dollman, J. In Search of Consistent Predictors of Children’s Physical Activity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2017, 14, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, B.M.; Bengoechea, E.G.; Julián Clemente, J.A.; Lanaspa, E.G. Empowering Adolescents to Be Physically Active: Three-Year Results of the Sigue La Huella Intervention. Prev. Med. 2014, 66, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, C.K.; Garside, H.; Morones, S.; Hayman, L.L. Physical Activity Interventions for Adolescents: An Ecological Perspective. J. Prim. Prev. 2012, 33, 111–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, D.R.; Steckler, A.; Cohen, S.; Pratt, C.; Felton, G.; Moe, S.G.; Pickrel, J.; Johnson, C.C.; Grieser, M.; Lytle, L.A.; et al. Process Evaluation Results from a School- and Community-Linked Intervention: The Trial of Activity for Adolescent Girls (TAAG). Health Educ. Res. 2007, 23, 976–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeroy, K.R.; Bibeau, D.; Steckler, A.; Glanz, K. An Ecological Perspective on Health Promotion Programs. Health Educ. Q. 1988, 15, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, S.J.H.; Atkin, A.J.; Cavill, N.; Foster, C. Correlates of Physical Activity in Youth: A Review of Quantitative Systematic Reviews. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2011, 4, 25–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Prochaska, J.J.; Taylor, W.C. A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, 963–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turbeville, S.D.; Cowan, L.D.; Greenfield, R.A. Infectious disease outbreaks in competitive sports: A review of the literature. Am. J. Sports Med. 2006, 34, 1860–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, M. Physical Literacy: Throughout the Lifecourse; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 978-0-203-88190-3. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferies, P.; Ungar, M.; Aubertin, P.; Kriellaars, D. Physical Literacy and Resilience in Children and Youth. Front. Public Health 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollman, J.; Lewis, N.R. The Impact of Socioeconomic Position on Sport Participation among South Australian Youth. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2010, 13, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, G.; Grønfeldt, V.; Toftegaard-Støckel, J.; Andersen, L.B. Predisposed to Participate? The Influence of Family Socio-Economic Background on Children’s Sports Participation and Daily Amount of Physical Activity. Sport Soc. 2012, 15, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, N.L.; Tamminen, K.A.; Black, D.E.; Mandigo, J.L.; Fox, K.R. Youth Sport Parenting Styles and Practices. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2009, 31, 37–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobin, E.; Leatherdale, S.; Manske, S.; Dubin, J.; Elliott, S.; Veugelers, P. A Multilevel Examination of Factors of the School Environment and Time Spent in Moderate to Vigorous Physical Activity among a Sample of Secondary School Students in Grades 9–12 in Ontario, Canada. Int. J. Public Health 2012, 57, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocca, R.; Dhanraj, T. 3 Reopening Plans for Ontario Schools Being Considered, Some Online Learning Expected to Continue. Available online: https://globalnews.ca/news/7084272/ontario-plan-reopening-schools-september/ (accessed on 22 June 2020).

- Eime, R.M.; Harvey, J.T.; Brown, W.J.; Payne, W.R. Does Sports Club Participation Contribute to Health-Related Quality of Life? Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, D. Adolescent thinking. In Handbook of Adolescent Psychology; Lerner, R.M., Steinberg, L., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; Volume 1, pp. 152–186. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas, A.; Laberge, S. Social Class and Ageing Bodies: Understanding Physical Activity in Later Life. Soc. Theory Health 2005, 3, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, A.; Turner, B.S. Aging in post-industrial societies: Intergenerational conflict and solidarity. In The Welfare State in Post-Industrial Society; Springer New York: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Distinction, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Juniu, S. The transformation of leisure. Leisure/Loisir 2009, 33, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legg, J.; Snelgrove, R.; Wood, L. Modifying Tradition: Examining Organizational Change in Youth Sport. J. Sport Manag. 2016, 30, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).