Abstract

Although it is well recognized that organizational culture is important for ensuring corporate sustainability, most existing models on an organizational culture do not have a sustainability-oriented organizational culture. While a few models about sustainability organizational culture are available, they focus on a particular aspect of the sustainability organizational culture (e.g., strategy, practice). To fill in the gap in the literature, the present study aims at developing a sustainability organizational culture model. It identifies components of a sustainability organizational culture, develops an Integrated Sustainability Organizational Culture model, and explores the model by adopting the case study approach, mixed data collection methods, and the working analytical framework. As an empirical contribution, findings indicate that, through a widely shared organizational culture, the sustainability organizational vision and values drive emotionally committed organizational members to perform corporate sustainability practices that lead to enhanced Triple Bottom Line outputs, satisfied stakeholders, and brand equity. As a theoretical contribution, the empirically endorsed Integrated Sustainability Organizational Culture model provides directions for further theoretical development. Managerial implications are discussed.

1. Introduction

The over-consumption of limited natural resources, increasing global population, economic growth, and trade activities have resulted in detrimental environmental, social, and economic consequences [1]. Increasingly, corporate leaders have recognized that corporate sustainability is critical for the future of their corporation [2,3] as it can serve as a source of opportunity or a source of threat to sustainable competitiveness [1], depending on how it is managed. To remain competitive in the global market where global buyers and supply chains are increasingly aware of sustainability issues and, thus, require more stringent social and environmental requirements [4], successful businesses manage to turn such a threat around into a source of a competitive advantage over their counterparts by managing their business operations according to the requirements. Empirically, such management for sustainability brings about immediate benefits, including financial savings, reduction in solid waste generation, and improvement in working/health conditions and product improvements [4].

Given the sustainability issues, corporations have been struggling to move away from the prevailing, wealth-maximization philosophy to a more inclusive corporate sustainability philosophy [5]. In doing so, many corporations that focus only on the “hard” side such as “green” technology-oriented solutions to integrate sustainability in their operations failure [6]. The success, on the contrary, is heavily influenced by managing the “soft” side, such as the organizational knowledge, organizational culture, attitudes and behavior, and internal human networks usage [6,7,8,9].

In particular, organizational culture has been singled out as the most important factor responsible for organizational success or failure [10]. Empirically, Avery and Bergsteiner [11] identified organizational culture as a foundational practice that drives sustainable enterprises. From their research of 47 sustainable enterprises, they revealed that sustainable enterprises nurture a consistent, clearly articulated, and widely shared organizational culture with non-negotiable core values. Further empirical evidence also endorses organizational culture as a driver of enhancing corporate performance [12,13,14].

Clearly, organizational culture is related in some complex ways with corporate sustainability performance [15,16], as it can adversarially affect corporate sustainability [6] or be conducive to achieving it [17]. Even though many corporate leaders realize that corporate sustainability can be achieved through a sustainability organizational culture, and that corporations need to align the decision with the organizational culture to ensure sustainable development [18], they have been struggling to incorporate sustainability into their organizational culture [8]. The present study explores this relatively unknown area to provide new insights and managerial implications for corporate leaders, which are significant contributions to the field.

Since we know that (a) organizational culture strongly influences sustainability implementation [8], (b) a gap exists in the broad theoretical and empirical literature on what organizational culture components drive toward corporate sustainability are [9,19], and (c) there is limited research on how to embed sustainability in and organizational culture [20], our research questions are below.

- What are components of sustainability organizational culture?

- How do the components lead to improving corporate sustainability performance?

Adopting the case study approach, our main research objectives are threefold: (a) to identify the components of sustainability organizational culture, (b) to explore their relationships with corporate sustainability performance, and (c) to develop a sustainability organizational culture model. The following sections discuss background literature, research propositions, methodology, the sample, and the findings. Future research directions and managerial implications are finally discussed.

2. Background Literature

Our literature review, guided by a theory of corporate sustainability [13], starts with corporate sustainability performance, followed by sustainability organizational culture where we introduce sustainability organizational vision and values, and corporate sustainability practices. These elements are introduced one by one below. In addition, emotional commitment and stakeholder satisfaction are also discussed, which is relevant in the corporate sustainability practice discussions.

2.1. Corporate Sustainability Performance

Corporate sustainability is a long-term, continuing matter. Essentially, long-term, continuing success depends on how corporations can successfully fulfil the needs of a broad range of stakeholders [21]. The necessity of balancing among the economic, social, and environmental outputs is underlined by the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) concept [22,23]. Theoretically, economic development occurs in relation to the planet and people. In essence, sustainable development requires environmental, social, and economic sustainability. For many scholars and practitioners, TBL is regarded as the central corporate sustainability performance measure [24]. Many corporations hoping to sustain their success report their social, environmental, and economic outputs. Therefore, TBL outputs are adopted as a corporate sustainability measure in the present study.

In addition to TBL, a corporate brand is regarded as essential for corporate sustainability because it involves functional and emotional benefits. These days, competitiveness via functional benefits alone is not sufficient to ascertain corporate sustainability in the cut-throat market place. Since business is an entity operating within the society, any of its practice should advocate a promising future for the entire society [25]. Therefore, any corporate activities beneficial to stakeholders contribute to achieving corporate sustainability as stakeholders are the foundation of society. They advocate and guard the reputation of a virtuous corporation [26,27]. Corporate brand equity, which is a measure of the strength of stakeholders’ attachment to a brand, can be achieved by fulfilling a variety of stakeholders’ needs [28]. Essentially, brand equity is a key success indicator of a corporation as perceived by stakeholders [28]. Given this reason, brand equity is increasingly regarded as a corporate sustainability performance indicator [12,29]. It is also related to other major sustainability indicators such as the capacity to deliver public benefits [30]. Therefore, we adopt brand equity as another sustainability performance measure in the present study.

2.2. Sustainability Organizational Culture

Organizational culture plays a pivotal role in ensuring corporate sustainability since it outlives any one individual [12,31]. To some scholars [10], organizational culture is regarded as the single most important factor responsible for organizational success or failure. However, most existing models on organizational culture are simply about general organizational culture [10,32]. While a few models specifically on sustainability organizational culture are also available, they focus on a particular aspect of a sustainability organizational culture. For example, Baumgartner [7] focuses on corporate sustainability strategies in developing a sustainability organizational culture, while Bertels et al. [20] focus solely on business practices. Notably, none of the existing models addresses an approach on how to manage sustainability organizational values fundamental to sustainability organizational culture, except one [12] that is to be discussed in the sustainability organizational values subsection below.

In terms of managing a sustainability organizational culture, it is well recognized among scholars and practitioners that vision and value statements are used by sustainable corporations to manage their culture [33,34]. They use them to covey core beliefs and unwritten rules [33,34]. More critically, a vision statement is always the start of a great culture [34] as it guides organizational values and serve the whole organization with a higher-order purpose. Both vision and values, in turn, inform all corporate decision making. Not only organizational members, but the vision can keep stakeholders oriented when it is deeply genuine and prominently displayed [34]. While a vision conveys the higher-order purpose, values work to guide and shape the behaviors and mindsets of organizational members and often stakeholders to attain that vision [34].

Mounting empirical evidence [11,33] also confirms that a “vision” or a mental model widely shared throughout the organization is espoused by sustainable enterprises as part of a widely shared corporate culture to effectively deal with uncertainties. Such a culture has core values as its underlying principles. These enterprises use vision and core values to guide their daily decision-making and operations, particularly observed when tradeoffs among goals are required. Therefore, sustainability vision and values are connected, as they form the foundation of an organizational culture.

2.2.1. Sustainability Vision

With the definitional confusion, vision is defined as a mental picture of a desired future for an organization [35,36]. Theoretically, sustainability organizational vision statements are composed of content and attributes [35,36]. As for vision content, the sustainability vision statements contain imagery about increasing stakeholder satisfaction [36]. The more imagery there is about satisfied corporate stakeholders contained in a vision, the more enhanced the prospect of corporate sustainability is [35,36]. As for vision attributes, effective sustainability vision statements are characterized by brevity, clarity, challenge, abstractness, future orientation, stability, and ability to inspire or desirability [35,36,37,38]. Each attribute and content of stakeholder satisfaction imagery interact to facilitate the vision communication process to create a formation for sustainable organizational culture and a positive impact on organizational performance [35,36] and corporate sustainability [36]. The theoretical process is explained below.

First, organizational members are reminded about the necessity of keeping a broad range of stakeholders satisfied via vision content of stakeholder satisfaction imagery [36]. When they are reminded, they are also motivated. Brevity permits organizational members to understand a vision message quickly since vision can be communicated massively, continuingly, and frequently [35,36,39], while clarity assists in ensuring that organizational members share the same prime goal to foster sustainability [35,36,40,41]. Organizational members can feel a sense of longer-lasting goal via vision abstractness [35,36,39]. Abstractness also assists them to form a coherent organization, and allows individually creative interpretations of the same vision to achieve sustainability goals. With challenging sustainability vision, organizational members are intrinsically motivated to carry on, particularly in a time of great difficulty [35,36,41,42,43]. Organizational members are also reinforced to take a long-term view, via future orientation [35,36,40,44], necessarily required for corporate sustainability. Ability to inspire attracts organizational members to work toward a sustainability vision [35,36,42,43]. They are allowed to grasp the meaning and outcome of their work. Finally, stable sustainability vision prevents organizational members from being confused [35,36,39] while they are executing vision-critical strategies and initiatives.

A shared vision as a result of the vision communication process facilitated by the seven vision attributes and content forms a foundation for a sustainability organizational culture [36]. Sustainability vision attributes, vision content, and their definitions are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions for sustainability vision attributes and content, adapted from a prior study [36].

2.2.2. Sustainability Values

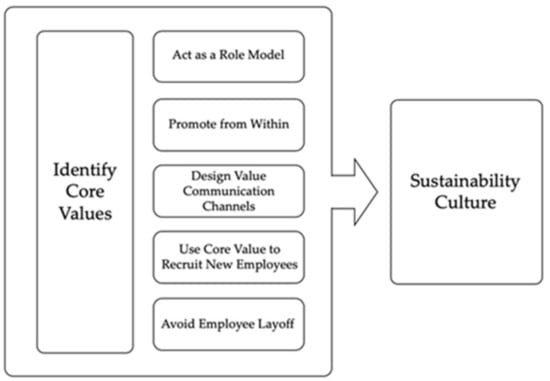

As discussed earlier, given that no other existing sustainability organizational culture model addresses an approach of how to manage sustainability organizational values, we adopt the approach in Figure 1 below [12] in the present study.

Figure 1.

Organizational values management framework ([12], p.13).

First, sustainable businesses identify a range of virtues, innovation, responsibility for the society, and environment as their core values [11,45]. These values are what sustainable businesses consider desirable, and praised and held in high esteem. With such a shared set of core values, sustainable corporations become a “special place to work” [32]. This “specialness” as perceived by organizational members is significantly different from one corporation to another, since it is based on the details of individual organization’s philosophy, vision, and values.

Virtuous values are, for example, altruism, empathy, reciprocity, as well as private self-effacement [46]. Altruism includes self-interest, and is conditional and discretionary [47] in that it expects reciprocal support and mutual concern. Empathy takes a perspective that assists combined efforts and shared perceptions, and, at the same time, allow for the pursuit of individual and organizational goals [48] or self-actualization, which is the top level of motivational needs [49]. The reciprocity value suggests avoidance of damage to the society and the environment, while stimulating a collaborative attitude that advocates exchanges benefiting all [50]. A private self-effacement value suggests that organizational members do not call attention to themselves and hold a modesty norm [46]. Concurrently, while still being agreeable and sensitive to others’ concerns and having an internal locus of control, private self-effacement rises above excessive modesty that can possibly take place with self-transcendence. These virtuous values help to advance individual pursuits, generate mutually agreed upon practices, and ensure organizational sustainability.

The values of innovation and social and environmental responsibility are frequently found interrelated in sustainable corporations [11], as the type of innovation they produce is one that deals with the existing social and environmental issues. They promote creativity, open communication, and ethical behavior that concerns accountability for a wide range of stakeholders [11]. These values are often exhibited in a form of social and environmental innovation where organizational members sharing all three sustainability values innovate their services, products, and processes as solutions to the existing social and environmental problems [51]. Notably, the social and environmental responsibility and innovation are also consistent with the virtuous value of the reciprocity value that suggests avoidance of creating harm to the society and the environment discussed earlier.

To nurture the sustainability values, corporate leaders always act as a role model to exemplify the sustainability values. Sustainable corporations also opt to grow their own leaders and managers to carry on their widely shared corporate cultures [11]. To keep echoing the values in the minds of organizational members, they carefully design various communication channels such as poems, songs, symbols, and shared events [52]. Besides, the core values are identified as criteria in selecting new organizational members to ensure they get only those sharing the corporation’s existing values and strategic direction [33]. Staff layoff is avoided to preserve the core values [11].

Since sustainability visions and sustainability values facilitate the vision and values sharing among organizational members, the organizational members become emotionally committed to the vision and values. Empirically, effective communication of vision and values is positively associated with emotional commitment, an emotional attachment, and desire to remain with the organization, among organizational members in a large variety of cultures and settings [52,53,54,55]. Effective vision and values communication also raises the level of the intrinsic value related to goal achievement and creates a higher level of individual commitment among organizational members to a common vision and organizational goals [56]. Therefore, the following proposition is formed.

Proposition 1.

Communication of sustainability visions and values lead to emotionally committed organizational members.

2.3. Corporate Sustainability Practices

In general, organizational values underlie and guide both personal and work behaviors of organizational members who share a vision, and are likely to be encapsulated over time in management practices [46]. In our case, the personal and work behaviors of organizational members who share the sustainability vision are underlined and guided by the sustainability values. As a result, the sustainability values are theoretically encapsulated over time in management practices called corporate sustainability practices.

According to the corporate sustainability theory [13], sustainable corporations adopt the Perseverance, Moderation, Resilience Development, Geosocial Development, and Sharing practices. We adopt this set of corporate sustainability practices since it is more inclusive, as shown in Table 2, than the individual existing practices, which focus on a particular aspect of sustainability such as sustainable reporting, sustainable supply chain management, eco-innovation, and risk management. Theoretically, organizational members who, via the sustainability vision and values, are emotionally committed to perform these practices. Therefore, the following proposition is formed.

Table 2.

Corporate sustainability practices [13].

Proposition 2.

Sharing the sustainability vision and values, organizational members are emotionally committed to perform the five corporate sustainability practices to realize the sustainability vision.

We assert that these corporate sustainability practices are influenced by the sustainability vision and values, as explained below. Each is followed by a relevant proposition.

2.3.1. Perseverance Practice

Perseverance is fundamentally critical for both start-up and established corporations in ensuring their continuing success [13,78], particularly with an inspiring and future-oriented sustainability vision and when the corporate environment is continuously changing. Perseverant organizational members continuously enhance services, processes, and products for their broad range of stakeholders, consistent with the existing practices of social innovation [58,59] and eco-innovation [60,61]. With the shared vision content of stakeholder satisfaction imagery, intrinsic motivation, the doing of an activity for its inherent satisfaction, and aspirations among organizational members suggest a sense of relationship, individual growth, health, and society. In essence, the achievement of goals linked to relationship, individual growth, health, and society brings about higher satisfaction of psychological well-being than the achievement of other goals linked to wealth, image, and recognition [78]. Really, the pursuit of goals associated with wealth, image, and recognition demoralizes the prospect of sustainable well-being [79,80,81,82]. These self-motivated individuals, driven by the sustainability vision, always find a logic and strength to continue a difficult task by never giving up or requiring external factors to motivate them. They, in theory, are able to do so because they live a shared organizational vision. Such on-going, intrinsic motivation in individuals brings about corporate perseverance behavior, leading to improved TBL outputs and, therefore, a corporate sustainability prospect. Endorsing this view, an alignment between the values of individual employees and their corporation is needed to nurture continuing intrinsic motivation among them, improving the corporate sustainability prospect [12].

Proposition 3.

Committing to the sustainability vision and values, organizational members perform the perseverance practice to bring about improved TBL outputs.

2.3.2. Resilience Development Practice

Resilience development points out the necessity to build immunity for oneself [13], consistent to the existing practices of risk management [68,69] and change management [70,71]. Resilience is a fundamental trait of self-reliant human beings, families, communities, and societies [83]. At a time of adverse events and calamities, they demonstrate resilient traits. Organizationally, resilience is well beyond bouncing back from a crisis. Instead, it suggests an ability of the organization to vigorously renew its organizational model as the external environment keeps changing [13]. Resilience development promotes self-reliance, sustainable development, and growth [84].

Resilient companies also promote self-leading and self-managing individuals [13]. Given that business corporations today are increasingly changing and becoming multifaceted, self-leading and self-managing individuals need to be responsive at different levels of the organization while maintaining an overall organizational coherence [84]. In such a context, independent thought is necessary under a sufficiently structured direction [85]. Such a structure is created only for prohibiting or redirecting ideas not supportive for the organizational direction or only those potentially damaging operations [85]. In a changing time, abstractness in sustainability vision allows the self-leading and self-managing organizational members sufficient autonomy, and, at the same time, the overall organizational coherence is ensured. This is because abstractness allows each individual organizational member to creatively interpret the sustainability vision to his/her own way to guide his/her daily work [36,86], nurturing organizational innovation. Often, the innovation is developed in response to changing social and environmental issues, eventually delivering TBL outputs. In the process, corporate sustainability is enhanced. Therefore, the following proposition is formed.

Proposition 4.

Committing to the sustainability vision and values, organizational members perform the Resilience Development practice to bring about improved TBL outputs.

2.3.3. Moderation Practice

The moderation practice is influenced by a future orientation in sustainability vision as it promotes a long-term organizational perspective in which both long-term and short-term consequences from corporate decision-making on various stakeholders are considered [36], which is consistent with the existing practice of risk management [68,69]. Adopting the moderation practice, corporations seek to balance between long-term and short-term performance. The moderation practice suggests that, at a time where corporations need to spend on improving the TBL ouputs to satisfy stakeholders, they will do so, even though doing so reduces short-term profitability for shareholders. Prudent operational and policy risk management is promoted by the future oriented sustainability vision, allowing the corporations to deal with the impact from unprepared hostile events better [36]. Sustainable corporations are led and managed to avoid threats and uncertainty [9]. Therefore, they espouse strategy formulation and planning for the long term. The top managers are reinforced to adopt a long-term perspective through a well-designed compensation and incentive schemes concentrating on the long-term sustainability. All aspects of sustainable corporations are influenced by the long-term perspective, ranging from strategy to daily operations [11,33].

The moderation practice adopts the process of prudent decision-making that considers long-term and short-term consequences on a wide range of stakeholders and corporation [13] to deliver the TBL outputs to ensure that the wide range of stakeholders is satisfied. Therefore, the following proposition is formed.

Proposition 5.

Committing to the sustainability vision and values, organizational members perform the moderation practice to bring about improved TBL outputs.

2.3.4. Geosocial Development Practice

Sustainability vision emphasizes the importance of stakeholders by including stakeholder satisfaction imagery as vision content [36]. Theoretically, the more a corporation envisions satisfying stakeholders via its entire operation, the better the corporate sustainability prospect. Such a sustainability vision influences the practice of sustainable corporations via the Geosocial Development approach that emphasizes corporate moral responsibility toward a wide range of stakeholders to ascertain sustainable development [13] in line with the sustainability values. Organizational members are reinforced by the sustainability vision and values in the minds to deliver the TBL outputs to keep stakeholders satisfied.

Adopting the Geosocial Development practice, corporations integrate the responsibility for the society and the environment in their entire operation and genuinely concern for their broad range of stakeholders, which is consistent with the existing practices of sustainability reporting [63,64], social innovation [58,59], eco-innovation [60,61], and sustainable supply chain management [65,66]. In general, sustainable corporations invest in keeping stakeholders satisfied to equip themselves with a sustainable competitive advantage [13]. Businesses that focus on defining and delivering values to a broad range of stakeholders strengthen their relationship with the society, ensuring their own sustainable success [87].

For sustainable corporations, a corporation is an entity operating within the society. It can exist only when the society exists. Thus, they are, via their operation, trying to satisfy a broad range of stakeholders comprising the society by balancing their demands. A successful balance, as a result, develops long-term, supportive stakeholder relationships that frequently rescue corporations in crises, ascertaining long-term, corporate sustainability. Therefore, the following proposition is formed.

Proposition 6.

Committing to the sustainability vision and values, organizational members perform the Geosocial Development practice to bring about improved TBL outputs.

2.3.5. Sharing Practice

Theoretically, sharing mainly refers to knowledge sharing internally within an organization and externally with a broad range of stakeholders [13], which consists of the existing practice of knowledge management [76,77]. The Sharing practice is enabled by the vision content of stakeholder satisfaction imagery and the sustainability values [36]. In sustainable corporations, knowledge sharing is required, leading to organizational innovation [9] that brings about a sustainable, competitive advantage for the corporations [88]. “Knowledge” mainly means implicit knowledge, which entails the things one knows but is not aware that he knows, embedded in organizational members’ heads [72]. This implicit knowledge is highly distinctive and challenging to reproduce or acquire because it is based on collective experience, context-specific, and part of exclusive operational procedures and processes. Thus, if strategically managed, implicit knowledge brings about long-term, sustainable competitiveness.

Sharing knowledge internally is an interactive process that requires skills, knowledge, and experiences of organizational members [89,90]. It helps to promote new ideas, nurture corporate learning, and identify best practices [89,90]. Externally, corporate innovation occurs by sharing knowledge and resources with a wide range of stakeholders [91,92]. The sharing corporations’ development and delivery of value are certainly influenced by the existence of a relationship network with different intellectual assets [93]. Knowledge management with stakeholder engagement results in an integration of multidisciplinary knowledge [94], frequently leading to improving TBL outputs.

In line with the stakeholder satisfaction imagery and sustainability values, co-opetition relies on a concept that cooperating competitors can create and share a total value [95], increasing overall market opportunities and reducing threats encountering all participating competitors [96]. Co-opetition via knowledge sharing can be in different forms, including collaborations, strategic alliances, clusters, and information exchange to improve performance for all cooperating competitors [97], frequently leading to improving TBL outputs. Co-opetition among competing, multi-national corporations may bring about reduced costs, threats, and uncertainties related to innovation during global expansion [75,98]. In many cases, it leads to rapid short-run efficiency improvements, merchandise innovation in domestic and overseas markets, and improved quality control [75,98]. Therefore, the following proposition is formed.

Proposition 7.

Committing to the sustainability vision and values, organizational members perform the sharing practice to bring about improved TBL outputs.

Overall, the TBL concept is based on the stakeholder theory [99] as the stakeholder theory [62] asserts that, to propel a firm forward to sustainable success, the firm should measure its performance in relation to stakeholders including local communities who demand a good environment and governments instead of merely employees, suppliers, and customers. The stakeholder theory suggests the firm to measure TBL outputs as part of its management to deliver outstanding performance. To deliver the TBL outputs, the firm is required to perform its practices toward satisfying the stakeholders. At the end, the delivery of TBL outputs satisfies the stakeholders. Therefore, we assert that the TBL outputs lead to satisfied stakeholders. The following proposition is formed.

Proposition 8.

The TBL outputs lead to satisfied stakeholders.

Based upon the resource-based theory [61], a firm’s relationships with multiple stakeholders drive corporate brand equity. According to the Dynamic Capabilities theory [100], stakeholder relationships result in dynamic capabilities, an organizational ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences in response to rapidly changing environments, that give rise to brand equity [101]. Since the delivery of TBL outputs satisfy the stakeholders, we assert that such positive relationships between the firm and its stakeholders lead to brand equity. The following proposition is formed accordingly.

Proposition 9.

Satisfied stakeholders lead to brand equity.

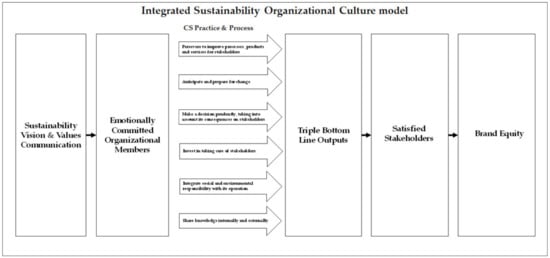

In summary, the following relationships can be derived from the literature review above. As part of the sustainability organizational culture, sustainability vision and values are communicated among organizational members. Then, organizational members who receive the sustainability vision and values messages become committed emotionally to the sustainability vision and values. Once committed, they act accordingly by performing the five corporate sustainability practices. It is these stakeholder-oriented practices that deliver the TBL outputs of environmental, social, and economic performance. These TBL outputs then satisfy the needs of a broad range of stakeholders whose relationships with the sustainable corporation determine brand equity. Given the literature review, the following Integrated Sustainability Organizational Culture model is developed for exploring, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Integrated Sustainability Organizational Culture model.

The model starts from left to right, theoretically, throughout the entire corporation. The sustainability vision and values are communicated among organizational members. Once sharing the vision and values, organizational members become emotionally committed to the vision and values. With their emotional commitment to the sustainability vision, they adopt the Perseverance, Resilience Development, Geosocial Development, Moderation, and Sharing practices. Since these five business practices are centered around satisfying the demands among stakeholders, sustainable corporations deliver TBL outputs, leading to improving the satisfaction among a broad range of stakeholders covering the society and the environment. Since brand equity is determined by stakeholders, satisfied stakeholders lead to improving brand equity.

3. Methodology

Given the nature of the research propositions, a holistic, in-depth investigation is required to explore. Therefore, the case study method is deemed appropriate for our present study that aims at exploring the theoretical process toward corporate sustainability [102]. We use a large, sustainable corporation, called Siam Cement Group (SCG), an introduction of which is discussed in the next section, as our sample.

The triangulation approach is adopted to ascertain a reasonable level of objectivity to enrich validity and improve thoroughness, depth, and breadth of the study [103]. We draw rich data from various perspectives, using several data collection approaches and data sources, or derive it from several viewpoints of different characters in a setting [104,105]. These data collection approaches are non-participant observation, reflective note taking, video-taping, critical incident technique, interview of current and former employees, and documentation, while data sources are both original and secondary data.

Specifically, we adopt the “Passive Presence” approach [106] during visits to SCG to collect observed data. Adopting the observation approach, we did not interact with the subjects being observed. However, they were aware of our presence. Video-taping and note-taking techniques were used to record observations and interviews (with interviewee permission). Additional qualitative data were also produced through critical incidents from the interviews and visits. Interview answers were also explored further via probes and document analysis results for rich, processual information. Field notes were re-written by the researchers into a more elaborated and readable form soon after they were collected to retain deep data that can still be retrieved even after the attention-catching moments that have faded from the researchers’ memories [107].

The researchers also conducted in-depth, semi-structural interview sessions with organizational members and stakeholders, of which the details are shown in Table 3 below. All were chosen conveniently since they were not under our control or influence. We also use our previously collected interview data from the sample conglomerate collected in 2005 and 2011 as part of our analysis in the present study to enhance the validity of the findings, given that an organizational culture emerges over time, shaped by organizational leaders and by actions and values contributing to earlier organizational successes [10], and our literature review indicates that some culture management practices in sustainable enterprises such as internal promotion, succession planning [12], and non-compromising core values [33] require a long period of time to validate.

Table 3.

Details about informants.

The framework approach was chosen for managing and analyzing the qualitative data [108]. Our framework is based on the theoretically and empirically pre-determined structure in Figure 2. Allowing for a constant validation of emerging themes, the pre-determined framework helps us to concentrate on the coding of those critical issues in the extant literature, and is highly relevant to the present study that aims to seek support for the theoretical model [109]. Based on the framework, we generated open-ended interview questions since we attempt to explore the propositions. An example set of interview questions is shown in Table 4 below.

Table 4.

Example interview questions.

The recorded interview data were transcribed first in Thai while the researchers were still fresh about behavioral responses of the interviewees and details. The transcription facilitated our subsequent analysis of the data. The researchers organize other types of data (e.g., earlier collected interview data, observations, and reflective notes) in a written form for subsequent analysis. The interviews were transcribed by the researchers themselves while they can draw meaning and understand slowly at the same time, given that the analysis of qualitative data generally takes place simultaneously with the data collection.

As a theoretically driven study, the model in Figure 2 is converted into a working analytical framework (Table 5). The working analytical framework is composed of distinct categories based on the model or codes. This working analytical framework is used to support our data management and organization.

Table 5.

A section of the working analytical framework.

In relation to sustainability vision components, the sample vision statement is rated by two researchers. The two researchers use a five-point ordinal scale in their rating, where 1 indicated absence of each attribute/content of stakeholder satisfaction imagery and 5 indicated a strong presence of each attribute/content of stakeholder satisfaction imagery. While rating, each researcher referred to the vision statement prototypes, adapted from a prior study [110] in Table 6 to rate the sample vision statement for the five attributes and content to ensure a reasonable level of consistency in their rating.

Table 6.

Vision prototypes ([110], p. 51).

We excluded the two-vision challenge and desirability attributes from our vision rating process because we opt to use data from the interviewees to rate them more precisely since organizational members know better whether the vision they share is challenging and desirable than outside raters. A five-point ordinal scale was adopted with one indicating an absence of stakeholder satisfaction imagery and each vision attribute while five indicate a strong presence. A consensus was sought via a discussion between the two researchers whenever there were contradicting views.

The next section introduces the Siam Cement Group (SCG), the sustainable enterprise, in which we collected the data to explore the propositions.

4. Siam Cement Group

Siam Cement Group (SCG) is selected as it meets the characteristics of a sustainable enterprise, according to prior studies [111,112]. It has the capacity to deliver competitive performance, maintain a market leadership, and endure difficult economic and social crises. Originally, as a cement producer, SCG has diversified its business into three main businesses: Cement-Building Materials, Packaging, and Chemicals. Globally, SCG is also the first conglomerate in ASEAN, comprising 10 Southeast Asian nations, invited by Dow Jones Sustainability Indices (DJSI) to be included as the Global Industry Leader in Construction Materials since 2004, making it a suitable subject for the present study.

Founded in 1913 by a royal decree of King Rama VI of Thailand, SCG initially produced cement, which is the material required for infrastructure projects highly in demand of the country during the development period. SCG is presently ASEAN’s oldest and largest cement and building material conglomerate. In 2016, SCG was additionally ranked by Forbes as the second largest conglomerate in Thailand and the 604th largest public conglomerate in the world. SCG’s major shareholder is the Crown Property Bureau, owning approximately 30% of its shares.

SCG’s reported consolidated earnings of 44,748 Million Baht (USD 1477 Million) in 2018, a drop of 19% year-on-year due to weaker performance of chemicals. However, revenue from sales, an increase of 6% year-on-year, registered at 478,438 MB (USD 15,792 Million). SCG’s profitability ratios stood at 9%, indicating corporate resilience. In 2018, SCG proposes an annual dividend payment of 18.00 Baht (USD 0.59) per share, indicating a payout ratio of 48%.

By contributing to the sustainable progress of the communities where it operates, SCG, as a leading business conglomerate in the ASEAN region, has committed itself to good corporate governance and sustainable development. It pledges to become a role model in corporate governance and sustainable development and an ASEAN business leader. With its longstanding tradition of learning, SCG has survived through crises and been regarded as a role model for other businesses.

SCG has heavily invested in the ASEAN region. For example, it has invested in cement plants around the regions, packaging businesses in Malaysia, and a petrochemical complex in Vietnam. SCG employs approximately 54,000 employees, providing products to the Thai market and exporting them globally. Most SCG’s joint ventures are with internationally renowned companies, including Toyota Motor, Michelin, Nippon Steel, Kubota, Siam Mitsui, and Dow Chemical Corporation.

5. Discussion

In this section, we discuss our findings by the corporate sustainability practices as informed by the sustainability vision and values, since theoretically the sustainability organizational culture is infused throughout the organizational activities. The culture’s underlying vision and values, emotional commitment among organizational members, stakeholder satisfaction, TBL outputs, and brand equity are highlighted where relevant as part of the discussion on each corporate sustainability practice. Where each proposition is addressed is also pointed out.

5.1. Organizational Culture

Consistent to the practice of other sustainable enterprises [11,33], SCG has systematically nurtured a very strong organizational culture characterized by a widely shared vision and underlying values. To preserve such a culture, a supporting management system for human resources is crucial. SCG is meticulous in its recruitment and selection processes to ensure that it employs and promotes only those who are competent and whose values align with those of the corporation. In-service training and development programs are designed to broaden employees’ technical knowledge as well as to sustain commitment to core values. The culture is so strong that new recruits who do not share the vision and values usually find themselves “unfit” and decide to leave the conglomerate.

“We aim to recruit talent and ethical individuals but smart people sometimes have a different mindset from what we are looking for or it may require a lot of adjustment or tuning. So, we use interviews to screen out. We have some tools and some tests. For me, this is a vital process to screen and let only ethical people join the company... Sometimes it’s a shame to let talent candidates go because they are really smart. So, even though we don’t actually feel that they perfectly fit with our culture, we let them go on and have a probation period like others. However, from my experience, it has been proven that this doesn’t work—either they couldn’t pass the probation or even if they did pass, they didn’t have a bright future here. So, those who are able to pass our selection process/criteria must be ‘really clean.”Former Corporate Human Resources Director II (2011)

5.2. Sustainability Vision

Based on the methodology discussed above, the SCG vision statement is given the following rated scores, as shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Rated scores for Siam Cement Group’s (SCG’s) 2019 vision statement.

SCG vision statement meets the definitions (Table 1) to varying extents as shown above, mainly due to the fact that it contains a number of smaller goals. As for challenge and desirability, clearly the interviews below indicate that SCG’s members are inspired and challenged by the sustainability vision. Therefore, the SCG’s vision is rated five for both desirability and challenge.

“Yes, my work is consistent to this vision under the circular economy concept and promise and passion for better. This includes innovation or new business ideas. I like the concept. I think it is possible, but I used to ponder if the circular economy can actually take place with SCG since we sell cement and construction materials that cannot be reused. However, having a vision like this is good so that we can try to turn it into reality in our work, products, and business ideas.”Digital Business Manager, SCG Cambodia (2019)

“I like the vision. It is quite challenging. But I think the (vision) statement is quite long. Difficult to communicate.”Manager, CPAC, SCG Cement—Building Materials (2018)

In terms of vision content, the vision statement indicates much about improving stakeholder satisfaction. Thus, it is rated five for stakeholder satisfaction imagery.

Since we define vision in the present study as a desired future picture of an organization, the vision statement is surely part of the future picture. Nonetheless, other vision ideas among SCG’s members now and in the past need to be taken into consideration to determine if the shared desired future picture of the organization exists. Example responses are below.

“When I first joined the company in 1975, … we already knew what our company had been emphasizing. For example, we focused on taking good care of our people, that is the first thing I know… Another thing is that we were trained to learn at all times. In those days, … it became a norm that we have to learn… We must produce quality products, better than others and also at lower costs. Our service must be impressive… We were taught to look after the surrounding communities… We have been doing these for almost 100 years now (at the time of the interview).”Former President of SCG Cement and former Chair of SCG Sustainable Development Committee (2011)

“People in the community praise SCG in many ways. They praise SCG as a company, not me personally. They said SCG people shared the same (virtuous) character. They wonder how SCG mold its people. I personally received this feedback.”Managing Director, SCG Lampang (2018)

Given the responses above, it appears that no matter how much time has passed, SCG’s organizational members still share a future picture of SCG that is to be a virtuous business. The shared future picture or “vision” at SCG exists, even though the declared vision statement does not fully meet all seven attributes. Findings also reveal that the vision and its associated values have been shared via other non-verbal ways of communication such as role modelling.

“Let me give you an example, Professor Sanya Dharmasakti, a highly respected former Chairman. Everybody could see clearly that he is an exemplar of honesty, integrity, sufficiency, simplicity, and, another one, mercy. Therefore, we, the company, were built in a sense that we had to be good too.”Former President of SCG Cement and former Chair of SCG Sustainable Development Committee (2011)

The present study’s findings reveal that the seven vision attributes contribute to the sustainable success of SCG, endorsed by other scholars [35,39] who assert that the attributes lead to improved organizational performance as they facilitate the vision communication process. The findings on vision content of stakeholder satisfaction imagery also contributes to the sustainable success of SCG, which is consistent with prior studies that an imagery in organizational members improve the aspect contained in the imagery, such as venture growth imagery [35,113]. In our case, the stakeholder satisfaction imagery appears to contribute to stakeholder satisfaction, of which the details are discussed later in this report.

5.3. Sustainability Values

“Adherence to fairness, dedication to excellence, belief in the value of the individual, and concern for the social responsibility” are SCG’s living core values. They originated from former leaders and become unwritten corporate traditions. They have been espoused in high esteem and put into practice by all organizational levels, starting from the Board of Directors, the management to employees.”

“They (core values) began to be clear when Khun Jarus Chuto and Khun Paron Israsena Na Ayudhaya were Presidents. These core values are reflected by the core values of our leaders.”Former President of SCG Cement and former Chair of SCG Sustainable Development Committee (2011)

“Values have been transferred to us… to the younger generation from the older generations through exhibited behaviors… It’s all about practicing and modeling. For example, when I first started the job in the training unit. It’s a normal practice that my senior staff told me to pay the hotel as quickly as possible and not to try to delay… This is how the core values were developed in me by showing an example.”Former Corporate Human Resources Director II (2011)

“We are very strict with ethical practices here. If we have a single doubt on an employee, this employee will not be considered for promotion… there was a case that an employee who was supposed to go for training abroad and didn’t go, but he made a reimbursement, a small one. He was fired. This kind of person just doesn’t fit here.”Former President and CEO and Board Member (2011)

As soon as the SCG management recognized that the existing culture ‘blocked’ them from being innovative, two additional values of “open” and “challenge,” whereby organizational members listen to others’ opinions as well as accept challenge and improve their work performance, which were included in response to the new SCG direction to become a regional leader in the Asian market. To this end, training courses are provided for SCG managers on being open-minded and patient so that they listen to what their subordinates say and praise them for their new ideas. The SCG’s core values are not only shared throughout the conglomerate but also expanded to its stakeholders as well.

“We have over 1000 business teachers who have been working with us. These people have the habits consistent with our values. Over the years, they continue to transfer the values to other communities.”Community Engagement Manager, SCG Lampang (2018)

Our findings indicate that the sustainability vision can be effectively communicated verbally through a vision statement and in other non-verbal ways, such as role modelling, symbols, and signs. As for the SCG case, the vision statement does not perfectly meet the seven attributes for an effective sustainability vision, but the vision or the desired future picture of SCG has been communicated through leadership modelling even before the existence of the vision statement. In a similar fashion, sustainability values have also been effectively communicated through leadership modelling since the early days of its establishment. Based on the findings above, SCG members, as well as stakeholders, appear emotionally committed to the sustainability vision and values.

The findings above are consistent to the broader literature on core values. The core values of adherence to fairness, dedication to excellence, belief in the value of the individual, and concern for the social responsibility at SCG are consistent to virtuous values found at other sustainable enterprises [11,45], such as altruism, empathy, reciprocity, and private self-effacement [46], which has been discussed earlier in the literature review section. The newly added values of “open” and “challenge” are also instrumental values to innovation, which is a value found in sustainable enterprises [11,45].

In addition, consistency is the way the values are communicated and nurtured at SCG as SCG leaders always act as a role model to exemplify the sustainability values. SCG also promote managers who shared the corporate values from within the corporation, which are endorsed by the broader literature that sustainable corporations also opt to grow their own leaders and managers to carry on their widely shared corporate cultures [11]. The SCG core value statement of “Adherence to fairness, dedication to excellence, belief in the value of the individual, and concern for the social responsibility” is also endorsed by the broader literature that various valued, communication channels [13,52] are designed to keep echoing the values in the minds of organizational members.

The findings above support Proposition 1 where we theorize that sustainability visions and values lead to emotional commitment among organizational members.

5.4. Corporate Sustainability Practices

Our findings reveal that the organizational members at SCG really perform the five practices of Perseverance, Geosocial Development, Resilience Development, Moderation and Sharing, while supporting Proposition 2. To explore Propositions 3–7, we explore their relationships with sustainability performance at SCG below.

5.4.1. Perseverance Practice

Perseverance has clearly been demonstrated throughout its entire conglomerate, starting from new product development, market expansion, and sustainable development initiatives for enduring difficult times. Supported by the shared sustainability vision and values, perseverance behavior at SCG is outstanding during the Asian economic crisis when the Thai government decided to float the Baht on 2 July 1997, initiating a financial crisis during that year. SCG was severely impacted as it had borrowed offshore and traded with foreign currencies. Given its collective individual efforts, how SCG persevered to survive the Asian economic crisis was extensively reported in a previous study [111].

More recently, the global economy in 2018 was volatile given the trade war between the USA and China, soaring interest rates, political issues in many countries, and a fluctuating oil price. In Thailand, signs of emerging risks associated with stagnant exports and declining incoming foreign tourists were observed in 2018. Focusing on financial stability and sustainable growth, SCG reported consolidated earnings of 44,748 million Baht (USD 1478.66 million, representing a drop of 19% year-on-year. The reason for the drop was primarily due to declining chemicals performance. However, sales revenue was reported at registered 478,438 million Baht (USD 15,809.57 million), representing an increase of 6% year-on-year. As a result, SCG’s profitability ratios were reported at 9% with corporate resilience. SCG’s 2018 sales revenue from other regions was reported at 86,155 million Baht (USD 2846.92 million), accounting for 18% of SCG’s total sales revenue as SCG perseveres to seek for new growth opportunities.

“I think the mindset and behavior of SCG people drive our culture and core values. So, the way we operate, even we have to put extra efforts to manage achievements. So, we prefer to do so in any case.”Director, Sustainable Development Office, SCG Lampang (2018)

In a normal time, SCG perseveringly emphasizes on developing additional innovative integrated solutions. SCG’s 2018 sales revenue from High Value-Added Products and Services (HVA) was reported at 184,965 million Baht (USD 6112.01 million), which is an increase of 5% year-on-year. The sales revenue from innovative solutions accounted for 39% of SCG’s total sales revenue, indicating SCG’s strong capacity to innovate.

“We are under the circular economy-the limited use of plastic. We encourage the use of degradable plastic. This is going to be a big challenge for us. Very challenging. Because we actually have SCG Chemicals, our big business unit. When we encourage people to reduce the use of plastic, it means we are minimizing our own business income and our business revenue. So, on the scientific side, we are trying to come up with some better products, alternative products, degradable. So, at the moment, we have a cautious mind.”Board Member (2018)

The perseverance practice at SCG is endorsed by the broader literature. SCG members persevere to go through a series of crises. Given its vision containing reference to satisfying stakeholders, SCG members appear to focus on goals linked to psychological well-being that theoretically leads to a higher level of satisfaction [114]. Consistent to the self-determination theory by Ryan and Deci [57] is that SCG members always find a logic and strength to continue their tasks by never requiring external factors to motivate them. The perseverance practice is also underlined by the existing corporate sustainability practices of social innovation [58,59] and eco-innovation [60,61].

5.4.2. Resilience Development Practice

The corporate sustainability practice of Resilience Development indicates the requirement to create immunity for oneself [13] through a process of anticipating and preparing for change. Organizational resilience at SCG goes much further than rebounding from a crisis, but demonstrates its capability to dynamically redevelop its business model while the surrounding circumstance keeps changing. SCG’s experience with the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis has helped the corporation in dealing with subsequent crises effectively and immunizing itself from further shocks. In 2008, the world economy plunged into a deep economic slowdown. As the global economic downturn and domestic political turmoil continued into 2009, SCG managed to achieve even better results the previous year, reporting total revenues of 238,664 million Baht (USD 6.8 billion) and a net profit of 24,346 million Baht (USD 695.80 million) by focusing on prudent financial management and ongoing expansion into new markets.

In terms of introducing new models of business, product innovation at SCG is often integrated with social and environmental responsibility such as SCG Eldercare Solution, a home innovation for the elderly, “Fest” food safety packaging, and toilets and bathroom fixtures for the elderly that suit their physical condition. These products are designed to deal with the changing environmental condition and the increasingly aged society.

To achieve its sustainability vision, the corporation encourages employees to direct and manage themselves, supported by the vision abstractness. Enabled by the shared abstract sustainability vision, devolved, consensual decision-making is part of the process. To allow this paradigm to succeed, employees must be well-informed. SCG, therefore, provides training opportunities for employees at all levels, even those close to retirement. SCG also sends its staff to courses at partner universities overseas such as Harvard, Duke, and Wharton at U. Penn. Young and talented employees may also be awarded scholarships to continue their higher education.

A self-governing team at SCG is evident when it encountered the 1997 Asian Economic crisis during which the entire top management team forewent their salaries and, later, decided as a team to step down on its own, acting as an advisory team to the new top management team. During that time, SCG did not stop sending its members for highly costly programs abroad, as it viewed the training programs that would help to develop its organizational members to catch up with the economy after the crisis was over. In other words, SCG has developed corporate immunity and resilience for itself.

“No, they didn’t stop training. They still sent us overseas for training during that time (1997 Asian Economic Crisis).”Former President, Cementhai Distribution (2005)

As an SCG long-serving independent board member noted in 2005, he felt comfortable being a board member here since everything was systematic. He explained further that SCG had a strong foundation and corporate governance with a professional top management team. Therefore, the conglomerate can continue to operate on its own.

SCG employees also broaden their work experience through job rotation, whereby each employee is assigned to work in a particular position for up to four or five years. Job rotation encourages employees to create new professional networks and learn how to deal with new tasks. The process of job rotation enables knowledge sharing. Those who do not rotate are not viewed positively.

“I have to rotate. Otherwise, I will not grow in this company. Regional assignments are often considered as part of promotion.”SCG member (2018)

In continuing the culture and ensuring business continuity, SCG identifies and develops the potential in its staff to fill key positions in the future. A result is observed in Table 4 where our interview data between 2005 and 2018 indicate that internal promotion abounds (e.g., a former CFO to the present CEO, a former CEO to a board member, and a director to the business unit president).

Comparatively, the Resilience Development practice at SCG supports the broader literature that resilience is a fundamental trait of self-reliant human beings, families, communities, and societies, and that, at a time of adverse events and calamities, they demonstrate resilient traits [83]. In our case, adverse events and calamities are the crises discussed above. The finding that SCG continuously introduces new models of business, particularly when the business environment continues to change, is also consistent with the Lewin’s Complexity theory [67], which suggests that, to survive at the edge of chaos, organizations have to respond continuously to environmental changes via a spontaneous self-organizing change. At SCG, resilience is more than just bouncing back from a crisis, but an organizational capacity to re-new its business model in response to the ongoing environmental changes. Clearly, the Resilience Development practice at SCG is also supported by the existing practices of risk management [68,69] and change management [70,71].

5.4.3. Moderation Practice

Moderation has been at the core of SCG operation since day one. It was founded by King Rama VI’s royal decree to manufacture cement for the country’s development. It has taken a long-term perspective throughout its entire history. Its goal is not to maximize short-term shareholder value at the expense of other stakeholders, but to maximize benefits for its wide range of stakeholders initially in Thailand and increasingly in ASEAN. In addition to SCG’s attempt to reduce the use of plastic and, thus, its revenue from selling chemicals discussed in the Perseverance section above, the Moderation practice can be supported by SCG dividend payouts shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Dividend distribution between 2014 and 2018.

Theoretically, the process of prudent decision-making involving carefully taking into account long-term and short-term consequences on the corporation and its broad range of stakeholders is advocated by the future oriented, sustainability vision [13], as opposed to simply maximizing short-term value for shareholders. Vision future orientation essentially reinforces prudent risk management and management of available opportunities at SCG, enabling the corporation to become less vulnerable to the ad hoc hostile event effects [13].

“They (shareholders) have never questioned (about sustainability projects). I think partly because we have spent a lot of efforts in communication… When we compare with the total budget allocated, and with the revenue. The ratios are in line with those of the international practice, a bit higher… But you don’t take SCG as a typical case of Thai corporations. Generally, it is known to be a good citizen.”Board Member (2018)

“We set retail sales price according to market price. It is not setting for maximizing profits. We only compare with competitor retails sales prices, and make it comfortable for our customers to own the modern form machinery to better their lives. If farmers do not have enough money, how can they buy our products? That is why we have acquired a high market share.”Former Marketing Officer, Siam Kubota (SCG joint venture) (2018)

In business expansion matters, being moderate, SCG proceeds cautiously. It starts developing a new market by taking goods to sell overseas and developing networks. For example, it sets up a branch and trade agencies, and a factory of a size to match projected demand in each country. It also calculates and manages operational and financial risks, taking into account laws and legal requirements in each country. At the same time, it creates SCG brand awareness.

The moderation practice at SCG is also supported by the long-term orientation practice of other sustainable enterprises where enterprises do not simply minimize short-term, shareholder value alone [11,45]. They are trying to find a balance between short-term and long-term profitability by taking into consideration the needs of a wide range of stakeholders covering the society and the environment. In doing so, they avoid potential risks associated with dissatisfied stakeholders, consistent with the existing practice of risk management [68,69].

5.4.4. Geosocial Development Practice

Geosocial Development is concerned with investing in stakeholders and integrating the accountability for the environment and society with a business operation. The stakeholder satisfaction imagery in sustainability vision affects the Geosocial Development practice adopted by SCG’s members, given that ethical responsibility for external and distal stakeholders has been emphasized from its inception, which is consistent with sustainability values. SCG attempts to keep echoing in the minds of its members to maintain and improve stakeholder satisfaction. To SCG, social and environmental responsibility sometimes means investing. As part of the delivery of TBL outputs, many of its business activities for the society and the environment are done. However, they are not required and even reduce short-term profits.

An example of such an initiative is the Skills Development School. A business under SCG Cement Building Materials is SCG Logistics that requires land transportations. Given that the national rate of road accidents increases each year, which is often caused by big trucks, SCG realizes that it can play a role in reducing road accidents. Therefore, it started the Skills Development School, which is a non-formal school, to train its truck drivers and outsiders who are interested in it. Courses are offered in Thailand and other ASEAN countries such as Vietnam and Cambodia.

At SCG, the social responsibility value prevails both at the headquarters and other provincial units. SCG Lampang, where we observed many signs and symbols representing its core values, is an example. As pointed out earlier, the value is often extended to its stakeholders, including business partners and the society.

“It is easy to do mining with a mine explosion. This approach also costs less. But you actually destroy one mountain after another. We have adopted the Semi-Open Cut approach that costs more for more than 20 years now. We actually dig down from the top of a mountain to get different minerals we need. This way, we reduce dust and save the environment. More importantly, since the mountains are still there, the windway and the scenery do not change.”Managing Director, SCG Lampang (2018)

Investments in the society and environment can be seen continued throughout the entire conglomerate, from one unit to another. Responsibility toward the society and the environment is often shown through personal characteristics of SCG employees, which is an indication of non-compromising core values found in sustainable corporations [33].

“We have had three Managing Directors (MDs), but one thing that is clear from the Board to SCG Lampang’s management committee is social responsibility. It is common that some agree, and others do not. However, once the policy is firm and clear, we have to continue. Some MDs may focus more on returns. Others may focus on CSR activities. We have to have KPIs. Overall, we have had experienced no resistance. Early on, we make sure everyone in SCG understand before we start doing the work. SCG Sustainability Policy is one of them.”Managing Director, SCG Lampang (2018)

SCG corporate social responsibility initiatives focus on supporting people in society to stand on their own. Giving them things or money has never been in its corporate policy.

“About 40,000–50,000 Baht (USD 1321.77–1652.21) per year per household. We have gotten better because, in the past, we didn’t have enough water. Now that we have this connected reservoir, we can do more. In some years, if we were diligent, we could make more… up to 300,000 Baht (USD 9913.24).”Farmer, SCG Lampang (2018)

SCG has also run a foundation for the society. It has supported many corporate social activities throughout Thailand and the region.

Clearly, SCG invests for the society as indicated by its proclaimed vision statement. Given SCG outstanding performance over the years, the Geosocial Development practice at SCG is endorsed by the stakeholder theory as it asserts that businesses that focus on defining and delivering values to a broad range of stakeholders strengthen their relationship with the society, ensuring their own sustainable success [87]. In particular, given SCG outstanding performance during crises, the Geosocial Development practice at SCG is endorsed by the broader literature that corporations that create and distribute wealth by seriously taking into account stakeholders’ concerns can enhance their financial performance [115]. Practically, the Geosocial Development practice at SCG is also consistent with the existing practices of sustainability reporting [63,64], social innovation [58,59], eco-innovation [60,61], and sustainable supply chain management [65,66].

5.4.5. Sharing Practice

At SCG, this sharing practice is not possible without the vision’s stakeholder satisfaction imagery and the sustainability values. Knowledge sharing is a given because it pushes for corporate innovation to support its regional vision. Internally, knowledge is shared through forums, meetings, and formal training where more experienced SCG members, starting from the CEO, train the less experienced ones.

“There are numerous courses taught by internal instructors scheduled each year. These courses range from succession planning and talent management, employee engagement, salary structure design to new product introduction.”Former Personal Assistant to inbound expat executives, SCG Chemicals (2018)

Externally, SCG has shared its knowledge and experience with other organizations to promote awareness about virtuous business conduct. Moreover, Sharing at SCG also extends to include how to turn the circular economy concept into reality by focusing on maximum utilization of resources throughout the supply chain, where TBL outputs are delivered.

“To turn the circular economy concept into reality, SCG has joined forces with other organizations to initiate collaboration and knowledge sharing, which we hope will lead to the economic, social, and environmental sustainability.”President and CEO (2018)

Knowledge sharing at SCG is beyond its fence to cover its surrounding communities wherever it operates. An example, as part of a Check Dam construction project to return forests to mountains in Lampang, is its attempt to help the villagers living in the communities nearby SCG Lampang to stand on their own. In addition to helping them revive the mountains and forests, SCG has taught the villagers to start and run a business, clearly utilizing its expertise. The result is stunning. Clearly, this sharing practice leads to improving the TBL outputs.

“The mom said thanks to the water from the check dam. In the past with no water, her son had to leave home for Bangkok to find a job. So, it was a problem for her family. And right now, with the water, her son and others came back home to earn a living for themselves by making drinking water. And this is one example of a social enterprise in this village.”Director, SCG Enterprise Brand Management (2018)

Evidence for coopetition is also observed at SCG joint venture called Siam Kubota, which is a provider of agricultural machineries such as multi-purpose riding tillers and rice transplanters for farmers throughout Thailand. It works with direct competitors, local part suppliers, by allowing them to be part of its Kubota family. Siam Kubota trains these competitors on production techniques such as capacity checking, double part consumption, model variety, and cost reduction. Through this coopetition, Siam Kubota cannot only ensure high-quality parts but also reduce delivery times significantly for its customers.

Consistent with the existing practice of knowledge management [76,77], the findings on sharing practice is endorsed by the broader literature. The fact that the sharing practice at SCG leads to innovation is supported by the literature that knowledge sharing is required for a sustainable enterprise [9] since it brings about a sustainable advantage for the corporations [88]. The finding that knowledge at SCG is shared through forums, meetings, and formal training where more experienced SCG members, starting from the CEO, train the less experienced ones is underlined by the literature that sharing knowledge internally is an interactive process that requires skills, knowledge, and experiences of organizational members [89,90]. It helps to promote new ideas, nurture corporate learning, and identify best practices [89,90]. In addition, the finding that SCG helps villagers in Lampang to build check dams and run a community enterprise to generate an income enough to stand on their own is endorsed by the literature that knowledge management brings about an integration of multidisciplinary knowledge [94], frequently leading to improving the society and the environment. In this case, knowledge on farming and business administration are integrated to improve the socioeconomic condition of the villages living in Lampang. Finally, the sharing practice found at the SCG joint venture called Siam Kubota is also endorsed by the literature on coopetition, which asserts that cooperating competitors can create and share a total value [95] to increase overall market opportunities and reduce threats facing all sharing competitors [96]. This is because sharing knowledge with competitors at Siam Kubota leads to ensuring high-quality parts and reducing delivery times to customers.

5.5. Corporate Sustainability Performance

As findings indicate above, the practices at SCG are consistent with the five corporate sustainability practices. Theoretically, we can expect to see its TBL outputs and brand equity delivered by the practices. To explore Propositions 8 and 9, findings on TBL outputs and brand equity at SCG are presented and discussed below.

5.5.1. Triple Bottom Line Outputs

In addition to the 2018 impressive financial figures reported earlier, its sustainability performance as measured by the TBL outputs in 2018 are shown in Table 9 below. The TBL outputs here are directly the results of the five corporate sustainability practices as pointed out earlier.

Table 9.

SCG examples of TBL outputs in 2018.

These TBL outputs are reported to the public by SCG, which is consistent with the practice of sustainability reporting [63,64]. Since the SCG vision contains an imagery about improving stakeholder satisfaction, many of the outputs above clearly lead to improving the society and the environment, endorsed by the sustainability vision theory [36].

5.5.2. Brand Equity

In terms of brand equity, findings below indicate that satisfied stakeholders, as a result of the delivery of TBL outputs, actually lead to improving brand equity. Over the years, SCG has continued to be the best brand, as determined by different organizations. A previous study [116] found that SCG’s corporate social responsibility initiatives such as SCG Water Preservation led to trustworthy brand and reputation. Moreover, it revealed that SCG had a clear brand personality leading to brand loyalty as the SCG brand met consumer expectation.

More recently, an annual SCG reputation survey for 2018 reveals that, of all 750 respondents drawn from SCG members (200), community members (150), the general public (300), university students (60), and media professionals (40), 93% perceives SCG as the Innovative Brand Leadership, as a reflection of the additional Open and Challenge values, and 95% as the Sustainable Development Brand Leadership. The SCG brand is determined by a wide range of stakeholders. When SCG’s core values reverberate with those of the stakeholders, strong brand equity is created [117,118]. Additionally, brands are dynamic entities developed via multiple stakeholders’ interactions internally and externally to the corporation [119,120]. These dynamics enhance brand value [121] at SCG.

The findings relevant to brand equity above are also supported by the broader literature that satisfied stakeholders advocating and guarding the reputation of a virtuous corporation [26,27] and that corporate brand equity can be achieved by fulfilling a variety of stakeholders’ needs [28].

6. Managerial Implications

Although our present study offers some important managerial implications for corporate practitioners who hope to ensure their own corporate sustainability, we highlight only a few major ones that are relatively unknown below.