Learning from Failure and Success: The Challenges for Circular Economy Implementation in SMEs in an Emerging Economy

Abstract

“For me, context is the key—from that comes the understanding of everything.”—Kenneth Noland

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Framework

2.1. Circular Economy (CE)

- CE Implementation

- From the concept to practice: The ReSOLVE framework

- Top-down: CE implementation in emerging economies

- Bottom-up: CE implementation in SMEs in emerging economies

2.2. The Role of SMEs in the Mexican Economy

3. Methodology

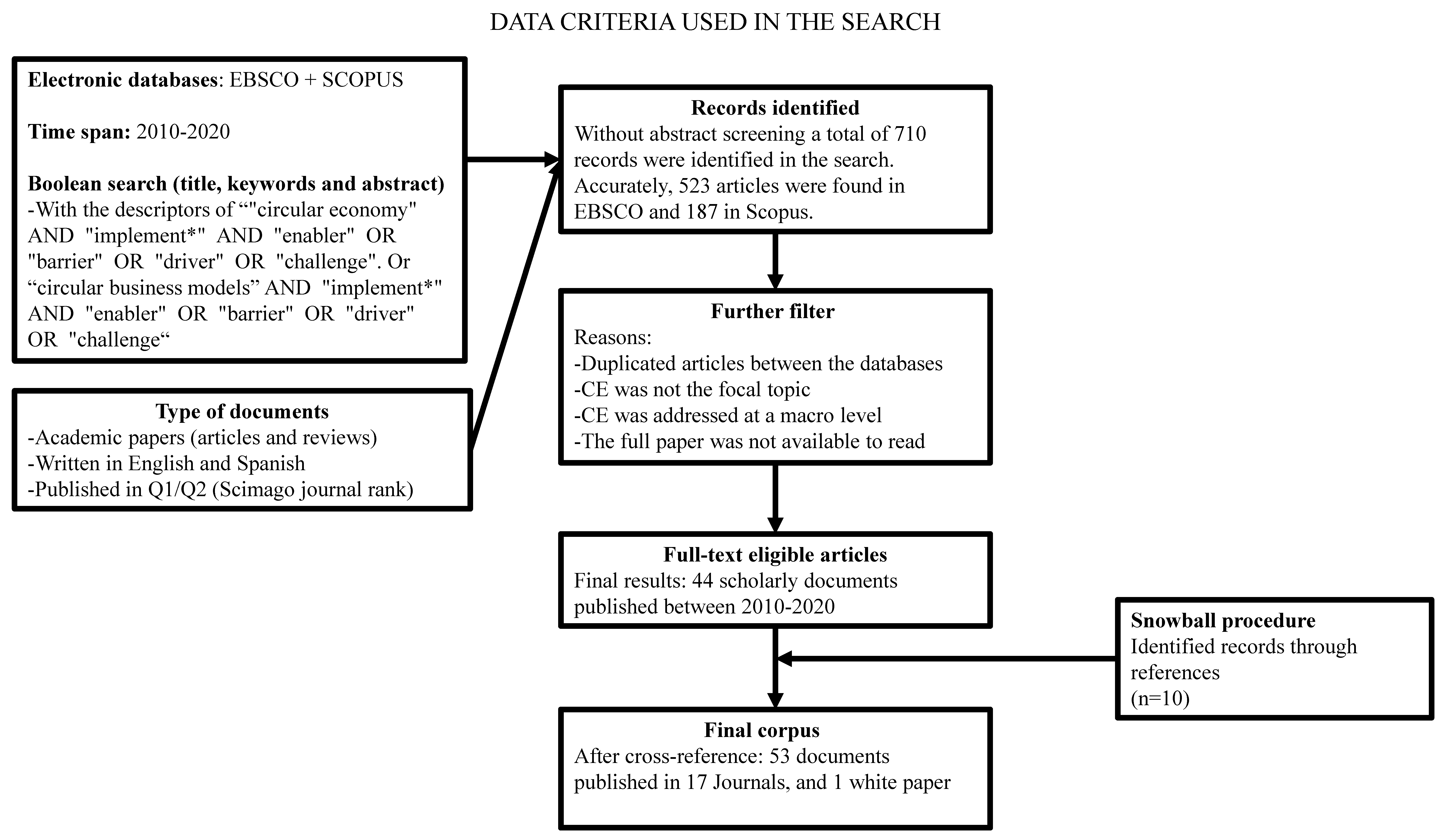

3.1. Phase 1: A Literature Review of CE Barriers and Enablers (The Codebook)

3.2. Phase 2: Empirical Stage

3.2.1. Sample Selection

3.2.2. Data Collection

3.2.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Phase 1: Theoretical Barriers and Enablers

4.1.1. External Barriers and Enablers

- User’s behavior

- Regulatory

- Infrastructure

- Economy and Competitive Markets

- Supply chain

4.1.2. Internal to the Firm

- Knowledge

- Financial

- Organizational

- Product and material characteristics

4.2. Phase 2: Empirical Barriers and Enablers

4.2.1. Empirical Barriers

- i.

- User’s Behavior

- Budget: users’ low ability to pay

“[T]here are people who tell us: ‘Hey, we like the bike, but it is costly do you sell other more affordable bamboo-items?”Company B

“There are people who do not care. (about the environment) all they say is: ‘your bikes are costly’ These people are perhaps more interested in the bike’s price there are others (people) that might not have the money to afford the product.”Company B

- Preference and demand: prevalence of a buy and own society

“One barrier was the culture or idea that ‘people are defined by their property,’ this part hit us very hard because people did not want to rent their things, even when they did not use them anymore... We have this culture of “owning” products. The more we have, the more we are.”Company D

- Preference and demand: consumers’ skepticism and lack of trust

“There was a person we invited to use the renting app to rent its camping tent, and we asked him:

Company D: ‘Hey When was the last time you used your camping tent?’

User: ‘Three years ago.’

Company D: ‘Why don’t you rent it?’

User: ‘Because it is my tent, and then what if they break it or do something to it?’

That was a very high barrier, and we could not understand that kind of people. They do not use it anymore, they have not used it for about three years, and they will have another income. They have the idea that something will happen to their things, even though there is a guarantee that their things would get repaired or replaced if that was the case.”Company D

“[P]eople like to touch and buy more than to see and buy. People do not know if the advertised product is real or not. This created uncertainty in the user.”Company D

- ii.

- Infrastructure

- Infrastructure irregularities

“Interviewer: Does the company consider the available waste collection mechanism or infrastructure to propose solutions?

Company E: Exactly. For instance, collecting textile would be problematic in Mexico… I mean, unless there was legislation or a mechanism to put a value on the textile waste to trigger collection centers’ emergence and prevent its dispersion. Its lack of value and its dispersion limits the possibilities. In the bagasse case, we collect it directly from the generating companies, as they have massive concentrations of this waste. If it were the case that Mexico was a textile production pioneer, you know that if you go to a company (such as the case of beer in Mexico), they will have concentrated textile waste in one place. Nevertheless, this is not the case in Mexico, so that is why it is not a project that is being considered to be carried out in Mexico.”Company E

- Lack of financial infrastructure and lack of access to financial services

“Our biggest barrier was the entire financial part of how to transfer payments. We needed to freeze a “security deposit” amount that we refunded to the user after the rental. However, several banks did not want to accept the system.”Company D

“[W]e required a credit card to make the rent, but only a small fraction of the population has a credit card…there are few cards in circulation right now.”Company D

- iii.

- Knowledge

- Poor understanding of CE

“I understand reuse or recycling. Back to the cycle. Have another transformation for a different use, that there is no end.”Company B

“We have not measured the environmental impact, but it could be measured using an environmental impact assessment.”Company E

“Interviewer: Any social benefit linked to the use of bamboo, and how do you measure it?

Company B: Well… the benefit… I do not know how much it can be measured or how can I measure it… but the people who harvest the bamboo receive a benefit from taking advantage of their raw material”.Company B

“[W]e are a company that manufactures and distributes bamboo activated carbon cloth diapers... we still do not manufacture this cloth here in Mexico, we still import it from China.”Company C

“[W]ell, we do not collaborate with our bamboo providers (to achieve CE initiatives) … I do not have data on how the bamboo (for the bikes) is obtained.”Company B

4.2.2. Leveraging Factors

- i.

- User’s Behavior

- Budget: Tackling users’ ability to pay through inclusive business models

“[T]he social benefit was that customers did not have to spend much money to have access to a product…So, low-income people could access high-value products.”Company D

“I believe that the most important thing (about the renting program) is going to be the exposure that our bikes will have in the streets, and that exposure could translate into more sales.”Company B

“[W]e capacitated our teams, that without knowing the carpentry profession, now have learned it. We capacitated some people that used to work at night as warehouse workers. Now they already have that trade and can make a living from carpentry.”

“[R]ight there in the workshop we have created spaces where we have been able to give lodging to the carpenters.”Company A

- Preference and demand: overcoming users’ skepticism and lack of trust through transparency and certifications

“People are the barrier… the first thing people ask or the first thing they think is if the bamboo bike is resistant…For those who believe the bike is not resistant, we have generated content to let them know otherwise. To let them know that we have US certifications that the bicycle works, of resistance… they trust a lot in the Americans.”Company B

“[I] do not know if it is luck or not, but customers have liked the brand. Also, they have shared through our webpage that they like that we are transparent and that we do not hide anything.”Company A

- Preference and demand: overcoming users’ reluctance to change by proposing added-value business models

“In Mexico, there is a minimal culture of caring for the environment... most of our diaper sales are not motivated for environmental reasons…thus, instead we are marketing the diaper based on the economic savings and the health aspect.”Company C

“[O]ur clients have the purchasing power to own a car, but they decide not to use it, or they could choose not to use it because they have a bicycle that can solve the (Mexico) city mobility problem.”Company B

- ii.

- Supply chain

- Collaboration

“We talked about this project with the owner of the sawmill, and he understood the project, so he reserved all the wood scrap for us.”Company A

“[W]e are going to call it cooperation but in reality, it is like a “partnership” … an association… because we would not be able to offer all our current services alone. Our company offers sustainable innovation in different aspects, but to achieve this we need experts in each area.”Company E

“Our company has an entrepreneurship area. For this part, we work with a company that is an expert in working with entrepreneurs and developing ideas into business models. In contrast, if we work with bioplastic or other technology, we go hand in hand with experts in such technology or reach out to scientists who have many years of experience working with a specific material or processes.”Company E

- iii.

- Organizational

- Management: acknowledge the problem

“I was in various cities in France and Europe and saw many bicycles. That form of mobility within cities caught my attention. When I returned to Mexico, I was found again with all the cars, the traffic, the high fuel cost, the inefficiency in mobility, public transport, and… I decided that I wanted to implement the use of the bicycle.”Company B

“We aim to create wealth for our company, and our city-state, by generating decent jobs in Mexico and by taking care of the environment. Above all that, we wish to improve the lives of Mexicans... that our families become healthier, that they improve their quality of life and their purchasing power.”Company C

- Strategies: lobbying and consumers’ education

“We are working with the chamber of senators and the chamber of deputies towards a law that aims to regulate disposable diapers… so these are no longer used in Mexico. In several countries, this is already the case.”Company C

“[M]exico, has a minimal culture of caring for the environment. We have had to face reeducation of the population. We have done this through social networks.”

“Reeducate people... To young girls, it is teaching them how to wash diapers. The benefits have been made known to them.”Company C

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions: Learning from Failure and Success

Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Identify which of the following activities have been used to some extent in any business unit of the firm:

- Identify what economic, social, and environmental benefits have directly generated CE practices, indicating how these benefits have been measured.

- Identify what internal and external barriers and enablers for CE implementation.

- 1.

- What is your understanding of the Circular Economy?

- 2.

- How many employees does your firm have?

- 3.

- In which industry does your firm operate?

- 4.

- What is your role in the organization (responsibility and hierarchy level)?

- 5.

- How long have you worked in _____?

- 6.

- What is your professional experience?

- 7.

- What activities has your firm implemented related to regeneration CE practices?

- 8.

- What internal factors have facilitated the implementation of regeneration practices in the firm?

- 9.

- What external factors have facilitated the implementation of regeneration practices in the firm?

- 10.

- What barriers did the firm have to overcome to implement regeneration practices?

- 11.

- What are the economic benefits? How do you measure them?

- 12.

- What are the social benefits? How do you measure them?

- 13.

- What are the environmental benefits? How do you measure them?

- 14.

- Did your firm try to implement regenerative CE practices and was not successful?

- 15.

- What barriers have impeded the implementation of regenerative practices in the firm?

- 55.

- Has your firm implemented any other practice that you consider related to CE that was not mentioned above?

- 56.

- Do you cooperate with suppliers for achieving the implementation of CE practices? If yes, in what activities? How?

- 57.

- Do you cooperate with customers to achieve the implementation of CE practices? If yes, in what activities? How?

- 58.

- Did you use any method to identify and implement CE activities? E.g., a consulting firm.

- 59.

- What was your motivation to implement CE practices?

- 60.

- To your understanding, what is the relationship between CE and sustainability?

- 61.

- What has been your overall experience with the implementation of CE in your company?

- 62.

- Do you have anything else you want to add?

Appendix B. Case Summaries

References

- Scheel, C.; Aguiñaga, E. A systemic approach to innovation: Breaking the rules of conventional regional development: The cases of Mexico, Colombia, India and Brazil. In International Cases on Innovation, Knowledge and Technology Transfer; Trzmielak, D.V.G., Ed.; Center for Technology Transfer UŁ: Łódź, Poland, 2015; ISBN 9788392237587. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation and McKinsey & Company. Towards the Circular Economy: Accelerating the Scale-up Across Global Supply Chains; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Scheel, C.; Aguiñaga, E.; Bello, B. Decoupling Economic Development from the Consumption of Finite Resources Using Circular Economy. A Model for Developing Countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L.M.; Domingues, J.P.; Pereira, M.T.; Martins, F.F.; Zimon, D. Assessment of circular economy within Portuguese organizations. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guldmann, E.; Huulgaard, R.D. Barriers to circular business model innovation: A multiple-case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa-Zomer, T.T.; Magalhães, L.; Zancul, E.; Cauchick-Miguel, P.A. Exploring the challenges for circular business implementation in manufacturing companies: An empirical investigation of a pay-per-use service provider. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieder, M.; Asif, F.M.A.; Rashid, A.; Mihelič, A.; Kotnik, S. Towards circular economy implementation in manufacturing systems using a multi-method simulation approach to link design and business strategy. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 93, 1953–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, M.A. Circular economy at the micro level: A dynamic view of incumbents’ struggles and challenges in the textile industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 833–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri, A.; Braccini, A.; Poponi, S.; Mosconi, E. A Meta-Model of Inter-Organisational Cooperation for the Transition to a Circular Economy. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieder, M.; Rashid, A. Towards circular economy implementation: A comprehensive review in context of manufacturing industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 115, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patwa, N.; Sivarajah, U.; Seetharaman, A.; Sarkar, S.; Maiti, K.; Hingorani, K. Towards a circular economy: An emerging economies context. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizos, V.; Behrens, A.; van der Gaast, W.; Hofman, E.; Ioannou, A.; Kafyeke, T.; Flamos, A.; Rinaldi, R.; Papadelis, S.; Hirschnitz-Garbers, M.; et al. Implementation of Circular Economy Business Models by Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs): Barriers and Enablers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominish, E.; Retamal, M.; Sharpe, S.; Lane, R.; Rhamdhani, M.; Corder, G.; Giurco, D.; Florin, N. “Slowing” and “Narrowing” the Flow of Metals for Consumer Goods: Evaluating Opportunities and Barriers. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermunt, D.A.; Negro, S.O.; Verweij, P.A.; Kuppens, D.V.; Hekkert, M.P. Exploring barriers to implementing different circular business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 222, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jesus, A.; Mendonça, S. Lost in Transition? Drivers and Barriers in the Eco-innovation Road to the Circular Economy. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 145, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormazabal, M.; Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Jaca, C.; Santos, J. An overview of the circular economy among SMEs in the Basque country: A multiple case study. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2016, 9, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Estadísticas a Propósito del día de las Micro, Pequeñas y Medianas Empresas (27 de Junio) Datos Nacionales; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI): Aguascalientes, Mexico, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Graafland, J.; Smid, H. Environmental Impacts of SMEs and the Effects of Formal Management Tools: Evidence from EU’s Largest Survey. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2016, 23, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Ellen MacArthur Foundation. The New Plastics Economy: Catalysing Action; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough, W.; Braungart, M. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things; North Point Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Benyus, J.M. Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature; Harper Perennial: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Frosch, R.A.; Gallopoulos, N.E. Strategies for Manufacturing. Sci. Am. 1989, 261, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressanelli, G.; Adrodegari, F.; Perona, M.; Saccani, N. Exploring How Usage-Focused Business Models Enable Circular Economy through Digital Technologies. Sustainability 2018, 10, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Resources, Conservation & Recycling Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiñaga, E.; Henriques, I.; Scheel, C.; Scheel, A. Building resilience: A self-sustainable community approach to the triple bottom line. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 173, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heyes, G.; Sharmina, M.; Mendoza, J.M.F.; Gallego-Schmid, A.; Azapagic, A. Developing and implementing circular economy business models in service-oriented technology companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 177, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, P.; Rutqvist, J. Waste to Wealth, 1st ed.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2015; Volume 4, ISBN 978-1-349-58040-8. [Google Scholar]

- The Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards a Circular Economy: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition; Ellen MacArthur Foundation: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Casiano Flores, C.; Bressers, H.; Gutierrez, C.; de Boer, C. Towards circular economy—A wastewater treatment perspective, the Presa Guadalupe case. Manag. Res. Rev. 2018, 41, 554–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Esposito, M.; Kapoor, A. Circular economy business models in developing economies: Lessons from India on reduce, recycle, and reuse paradigms. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 60, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, S.; Sergi, B.S.; Kapoor, A. Emerging role of for-profit social enterprises at the base of the pyramid: The case of Selco. J. Manag. Dev. 2017, 36, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyemang, M.; Kusi-Sarpong, S.; Khan, S.A.; Mani, V.; Rehman, S.T.; Kusi-Sarpong, H. Drivers and barriers to circular economy implementation: An explorative study in Pakistan’s automobile industry. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 971–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferronato, N.; Rada, E.C.; Gorritty Portillo, M.A.; Cioca, L.I.; Ragazzi, M.; Torretta, V. Introduction of the circular economy within developing regions: A comparative analysis of advantages and opportunities for waste valorization. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 230, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeudu, O.B.; Ezeudu, T.S. Implementation of circular economy principles in industrial solid waste management: Case studies from a developing economy (Nigeria). Recycling 2019, 4, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) Finance. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/smefinance (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Encuesta Nacional sobre Productividad y Competitividad de las MIPYMES (ENAPROCE). 2018. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/programas/enaproce/2018/doc/ENAPROCE2018Pres.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2020).

- Méndez Morales, J.S. Economía y la Empresa; McGraw-Hill: Ciudad de Mexico, Mexico, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlin, C. Guidelines for snowballing in systematic literature studies and a replication in software engineering. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, London, UK, 13–14 May 2014; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Baxter, P.; Jack, S. Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual. Rep. 2008, 13, 544–559. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, B. Trent Focus for Research and Development in Primary Health Care: An Introduction to Qualitative Research; Trend Focus: Nottingham, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Bai, Y. An exploration of firms’ awareness and behavior of developing circular economy: An empirical research in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 87, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Enterprises by Business Size. Available online: https://data.oecd.org/entrepreneur/enterprises-by-business-size.htm (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Pettigrew, A. Longitudinal field research on change: Theory and practice. Organ. Sci. 1990, 1, 267–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.Q.; Dumay, J. The Qualitative Research Interview. Qual. Res. Account. Manag. 2011, 8, 238–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, L.D.; Beyer, J.M.; Shetler, J.C. Building cooperation in a competitive industry: SEMATECH and the semiconductor industry. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 113–151. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.L.; Quincy, C.; Osserman, J.; Pedersen, O.K. Coding in-depth semistructured interviews: Problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociol. Methods Res. 2013, 42, 294–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Chen, H.; Hazen, B.T.; Kaur, S.; Santibañez Gonzalez, E.D.R. Circular economy and big data analytics: A stakeholder perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 144, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, M.; Jennifer, S.-D.; Cheryl, C.B. Content Analysis in Mass Communication: Assessment and Reporting of Intecoder Reliability. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2002, 36, 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbin, J.M.; Strauss, A. Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qual. Sociol. 1990, 13, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Chapter 4: Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology; Volume 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Shahbazi, S.; Wiktorsson, M.; Kurdve, M.; Jönsson, C.; Bjelkemyr, M. Material efficiency in manufacturing: Swedish evidence on potential, barriers and strategies. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 127, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pheifer, A.G. Barriers and Enablers to Circular Business Models. Available online: https://www.circulairondernemen.nl/uploads/4f4995c266e00bee8fdb8fb34fbc5c15.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Van Buren, N.; Demmers, M.; van der Heijden, R.; Witlox, F. Towards a Circular Economy: The Role of Dutch Logistics Industries and Governments. Sustainability 2016, 8, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J. Key Drivers for High-Grade Recycling under Constrained Conditions. Recycling 2018, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, W.; Aurisicchio, M.; Childs, P. Contaminated Interaction: Another Barrier to Circular Material Flows. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, C.T.; Luna, M.M.M.; Campos, L.M.S. Understanding the Brazilian expanded polystyrene supply chain and its reverse logistics towards circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 562–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranta, V.; Aarikka-Stenroos, L.; Ritala, P.; Mäkinen, S.J. Exploring institutional drivers and barriers of the circular economy: A cross-regional comparison of China, the US, and Europe. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, A.; Rossi, J.; Pellegrini, M. Overcoming the Main Barriers of Circular Economy Implementation through a New Visualization Tool for Circular Business Models. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, J.L.; Hopkinson, P.G.; Tidridge, G. Value creation from circular economy-led closed loop supply chains: A case study of fast-moving consumer goods. Prod. Plan. Control. 2018, 29, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moktadir, M.A.; Ahmadi, H.B.; Sultana, R.; Zohra, F.-T.-; Liou, J.J.H.; Rezaei, J. Circular economy practices in the leather industry: A practical step towards sustainable development. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 251, 119737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Sezersan, I.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Gonzalez, E.D.R.S.; AL-Shboul, M.A. Circular economy in the manufacturing sector: Benefits, opportunities and barriers. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 1067–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Hasanagic, M. A systematic review on drivers, barriers, and practices towards circular economy: A supply chain perspective. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 278–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissling, R.; Coughlan, D.; Fitzpatrick, C.; Boeni, H.; Luepschen, C.; Andrew, S.; Dickenson, J. Success factors and barriers in re-use of electrical and electronic equipment. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 80, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, M.; Longo, M.; Zanni, S. Circular economy in Italian SMEs: A multi-method study. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormazabal, M.; Prieto-Sandoval, V.; Puga-Leal, R.; Jaca, C. Circular Economy in Spanish SMEs: Challenges and opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Piscicelli, L.; Bour, R.; Kostense-Smit, E.; Muller, J.; Huibrechtse-Truijens, A.; Hekkert, M. Barriers to the Circular Economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU). Ecol. Econ. 2018, 150, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moktadir, M.A.; Rahman, T.; Rahman, M.H.; Ali, S.M.; Paul, S.K. Drivers to sustainable manufacturing practices and circular economy: A perspective of leather industries in Bangladesh. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 174, 1366–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahpour, A. Prioritizing barriers to adopt circular economy in construction and demolition waste management. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 134, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploeger, H.; Prins, M.; Straub, A.; Van den Brink, R. Circular economy and real estate: The legal (im)possibilities of operational lease. Facilities 2019, 37, 653–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, D.; Kumar, V.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Godsell, J. Towards a more circular economy: Exploring the awareness, practices, and barriers from a focal firm perspective. Prod. Plan. Control. 2018, 29, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, M.; Williander, M. Circular Business Model Innovation: Inherent Uncertainties. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2017, 26, 182–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukker, A. Product services for a resource-efficient and circular economy—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 97, 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piyathanavong, V.; Garza-Reyes, J.A.; Kumar, V.; Maldonado-Guzmán, G.; Mangla, S.K. The adoption of operational environmental sustainability approaches in the Thai manufacturing sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 507–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Ordoñez, I. Resource recovery from post-consumer waste: Important lessons for the upcoming circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nußholz, J.L.K.; Nygaard Rasmussen, F.; Milios, L. Circular building materials: Carbon saving potential and the role of business model innovation and public policy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 308–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Ripa, M.; Ulgiati, S. Exploring environmental and economic costs and benefits of a circular economy approach to the construction and demolition sector. A literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 618–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcés-Ayerbe, C.; Rivera-Torres, P.; Suárez-Perales, I.; Leyva-de la Hiz, D. Is It Possible to Change from a Linear to a Circular Economy? An Overview of Opportunities and Barriers for European Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise Companies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Hernández, O.; Romero, S. Maximizing the value of waste: From waste management to the circular economy. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 60, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, J.L.; Chiwenga, K.D.; Ali, K. Collaboration as an enabler for circular economy: A case study of a developing country. Manag. Decis. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazen, B.T.; Mollenkopf, D.A.; Wang, Y. Remanufacturing for the Circular Economy: An Examination of Consumer Switching Behavior. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2017, 26, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroszewska, M.; Chaja, P.; Dziadkiewicz, A. Sustainable energy management: Are tourism SMEs in Poland ready for circular economy solutions? Int. J. Sustain. Energy Plan. Manag. 2019, 24, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Putnam, E.; You, W.; Zhao, C. Investigation into circular economy of plastics: The case of the UK fast moving consumer goods industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Y.K.; Mangla, S.K.; Patil, P.P.; Liu, S. When challenges impede the process. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 995–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, M.; Court, R.; Wright, M.; Charnley, F. Opportunities for redistributed manufacturing and digital intelligence as enablers of a circular economy. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2019, 12, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, M.E.; Luna, P.; Soltero, V.M. Towards standards-based of circular economy: Knowledge available and sufficient for transition? Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020, 27, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusmerotti, N.M.; Testa, F.; Corsini, F.; Pretner, G.; Iraldo, F. Drivers and approaches to the circular economy in manufacturing firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 230, 314–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Geng, Y.; Lai, K. Environmental Supply Chain Cooperation and Its Effect on the Circular Economy Practice-Performance Relationship Among Chinese Manufacturers. J. Ind. Ecol. 2011, 15, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressanelli, G.; Perona, M.; Saccani, N. Challenges in supply chain redesign for the Circular Economy: A literature review and a multiple case study. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 7395–7422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, S.; Bahadir, S.C.; Bharadwaj, S.G.; Guesalaga, R. New product introductions for low-income consumers in emerging markets. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 914–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Encuesta Telefónica de Ocupación y Empleo (ETOE). 2020. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/investigacion/etoe/ (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Comisión Nacional Bancaria y de Valores (CNBV) and Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Encuesta Nacional de Inclusión Financiera. 2018. Available online: https://www.cnbv.gob.mx/Inclusión/Paginas/Encuestas.aspx (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Gradl, C.; Knobloch, C. Brokering Inclusive Business Models; One United Nations Plaza: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dunne, D. User-centred Design and Design-centred Business Schools. In The Handbook of Design Management; Cooper, R., Junginger, S., Lockwood, T., Eds.; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2011; pp. 128–143. [Google Scholar]

- Lofthouse, V.; Prendeville, S. Human-Centred Design of Products and Services for the Circular Economy–A Review. Des. J. 2018, 21, 451–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, C.; den Hollander, M.; van Hinte, E.; Zijlstra, Y. Products That Last Product Design for Circular Business Models; TU Delft Library: Delft, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Grabner-Kraeuter, S. The Role of Consumers’ Trust in Online-Shopping. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 39, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrete, L.; Castaño, R.; Felix, R.; Centeno, E.; González, E. Green consumer behavior in an emerging economy: Confusion, credibility, and compatibility. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. VAT Rates Applied in the Member States of the European Union. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/sites/taxation/files/resources/documents/taxation/vat/how_vat_works/rates/vat_rates_en.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- SEMARNAT. Diagnóstico Básico para la Gestión Integral de los Residuos (DBGIR); Instituto Nacional de Ecología y Cambio Climático (INECC): Mexico City, Mexico, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Scheel, C. Beyond sustainability. Transforming industrial zero-valued residues into increasing economic returns. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 131, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case ID | Sector | Number of Employees | Founding Year | ReSOLVE Initiative | Interviewee’s Position in the Firm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Manufacturing | 8–10 | 2014 | Optimize, Virtualize, Exchange. | Founder |

| B | Manufacturing | 5 | 2010 | Optimize, Virtualize, Exchange. | Founder |

| C | Manufacturing | 7 | 2013 | Regenerate, Optimize, Virtualize, Exchange | Founder |

| D | Services | 6 | 1.5 years before going out of business | Sharing and Virtualize | Founder |

| E | Services | 2 | 2014 | Exchange | Founder |

| Type of Barrier | Associated Issues | Empirical Evidence | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| External | |||

| User’s Behavior | |||

| Budget | - Low willingness to pay. | X | [8,12,13,14,15,23,34,42,52,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68] |

| - Preference to buy disposable products. | X | ||

| Preference and Demand | - Attitudes and conduct (e.g., the prevalence of a throw-away society). | X | |

| - Costumers rigidity, inertia, and reluctance to change. | X | ||

| - Ownership value (e.g., the prevalence of buy and own society). | X | ||

| Understanding and Perception | - Bad perception of recycled or reused products (e.g., unclean). | X | |

| - Lack of awareness in the environment or material recyclability. | X | ||

| Regulatory | |||

| Implementation | - Lack of law enforcement and poor accountability of governments. | - | [12,13,14,15,16,23,29,32,34,52,56,57,58,59,62,63,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79] |

| - Infrastructure does not support functioning CE. | X | ||

| - Government prioritizes short-term actions. | - | ||

| Incentives | - Lack of effective collaboration mechanism. | X | |

| - Limited funding for CE. | - | ||

| - Misaligned or no incentives to support CE (e.g., no incentive for using secondary material). | X | ||

| Political Landscape | - Unstable political condition or corruption. | X | |

| Promotion and Awareness | - Lack of education campaigns toward CE. | X | |

| Regulation | - Lack of regulations, standards, and laws, or mismatch between current legislation and legislation aimed at achieving a CE. | X | |

| - Lack of defined national goals to move toward CE. | - | ||

| Infrastructure | |||

| Infrastructure irregularities | - High costs linked to the recovery, transportation, and sorting of waste. | - | [8,13,15,16,23,32,56,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,70,75,79,80,81] |

| - Lack of effective collection, separation, and recovery infrastructure. | X | ||

| - Dispersion of post-consumer waste. | X | ||

| - Limited availability on quantity and quality of recycled material. | X | ||

| - The informal sector is not integrated into the waste management system. | - | ||

| Technology | - The lack and existence of appropriate technology to support CE. | X | |

| - Technology access (e.g., to separate the biological or technical mixes). | - | ||

| Economy and Competitive Markets | |||

| Capital and Funding | - Lack of access to capital and financing tools. | X | [10,12,13,14,15,23,32,42,57,58,59,61,62,63,66,67,68,71,75,80,81,82,83] |

| Market Competition | - Uneven playing field. Linear-based companies have more advantages over circular ones. | X | |

| - Competition from unregulated recovery sector. | - | ||

| - Arrangements in the waste and resource management market. | X | ||

| Market Trends | - Uncertainty about the marketplace (e.g., economic downturn). | X | |

| - Poor or little market demand for circular products. | X | ||

| - Low prices of recycled materials inhibit their collection and availability. | X | ||

| Supply Chain | |||

| Availability | - Existence of a “green” suitable supply chain. | X | [8,12,13,14,23,26,32,56,57,58,63,64,65,66,71,75,76,79,80,84,85] |

| Cooperation | - Lack of information sharing or data transparency. | - | |

| - Lack of supply chain integration, collaboration, and effects of supply chain complexity. | X | ||

| - Lack of trust and compatibility between partners. | X | ||

| - Current suppliers resist change. | - | ||

| - Power balance in buyer–supplier relationship and supply chain position. | - | ||

| Logistics | - Geographic dispersion and scope of global supply chains. | X | |

| - Difficulties associated with product traceability, collection, and storage. | X | ||

| - No reverse logistics in place. | X | ||

| Type of barrier | Associated Issues | Ref. | |

| Internal | |||

| Knowledge | |||

| Communication | - Asymmetric information and no communication among the employees or within the company’s departments. | X | [12,15,16,23,32,42,56,57,64,65,67,69,70,71,72,73,75,78,81,86,87] |

| Information access and awareness | - There is no awareness of CE or the environment. | X | |

| - Insufficient information management systems (e.g., lack of access to real data). | X | ||

| Information on CE | - No clear information on CE guidelines, performance indicators, and reference points. | X | |

| - Limited application of current sustainable business models and frameworks (e.g., CE frameworks might not be replicable in another context). | X | ||

| Financial | |||

| Investment Cost | - Large costs of investments associated with monitoring, machinery, transaction costs, investments, among others. | X | [6,12,13,14,15,23,26,42,52,68,71,76,82] |

| Revenue Model and Cost Structure | - Business model viability and profitability. | X | |

| Risk | - Risk associated with implementation, such as financial risks. | X | |

| - Cannibalization of own market share. | - | ||

| Organizational | |||

| Corporate Governance | - Administrative barriers (e.g., generating lease contracts). | X | [12,13,14,15,16,23,29,32,42,52,56,57,58,61,62,63,65,66,67,69,70,71,73,75,76,78,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88] |

| - Resistance of powerful stakeholders. | X | ||

| - Hierarchical system inhibits flexibility and innovation. | - | ||

| Culture | - Perception of sustainability as a cost and not as an investment. | - | |

| - Industry focus on end-of-pipe solutions. | - | ||

| - Silo mentality. | - | ||

| - Resistance to change. | X | ||

| Management | - Risk aversion of managers. | X | |

| - A linear mindset for top managers and lack of system thinking. | X | ||

| - Managers have limited knowledge of the CE concept. | X | ||

| - Limited environmental awareness of the directors and decisionmakers. | - | ||

| Organizational Capabilities | - Lack of expertise or skills. | X | |

| - Lack of training and education. | - | ||

| - Lack of organizational capabilities necessary for implementing circular business across different organizational functions. | X | ||

| Organizational Resources | - Lack of organizational resources (e.g., time and human). | X | |

| - Oversight and reluctance of operators’ employees. | X | ||

| - Employees have no support and guidance. | - | ||

| - Employment term limits imposed on managers affect long-term CE strategies | - | ||

| Strategies | - Lack of adaptation to local context or conditions. | X | |

| - Key performance indicators and accounting rules (e.g., the sales volume) focus on a linear economy. | X | ||

| - CE is not integrated into the strategy, mission, vision, or goals. | X | ||

| - Unclear or weak CE business model. | X | ||

| Product and Material Characteristics | |||

| Design | - Material and product complexity (e.g., too many types of plastic). | - | [8,13,23,32,56,57,59,63,67,68,71,75,76,79,81,85,87] |

| - Incorrect design of products (e.g., not designed for longevity, disassembly, or reuse). | - | ||

| - Design constraints or aesthetic issues (e.g., material substitution constrains). | X | ||

| Type of Enabler | Associated Issues | EmpiricalEvidence | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| External | |||

| User’s Behavior | |||

| Budget | - Consumers are willing to pay a surplus for CE products. | X | [14,15,23,32,64,66,67,68,69,72,76,85,87,89] |

| - Consumers are likely to switch to circular products if linear products have higher prices than circular products. | X | ||

| Preference and Demand | - Enhance collaboration with customers (e.g., personalized incentives and promotions to encourage customers to return packaging). | X | |

| - Increased public opinion and pressure. | - | ||

| - Cultural acceptance of circular business models, such as Product as Service. | X | ||

| - Consumers are likely to support circular business models (e.g., remanufacturing) if the linear product is of low utilization. | X | ||

| Understanding and Perception | - High environmental literacy and awareness. | X | |

| Regulatory | |||

| Implementation | - Government incentivizes and develops the needed infrastructure (e.g., waste management). | X | [10,12,15,26,29,32,34,57,59,60,61,62,66,67,69,72,80,81,84,85,87,90,91] |

| - Governmental long-term planning. | - | ||

| - Law enforcement. | - | ||

| Incentive | - Government funding for CE initiatives. | X | |

| - Tax benefits or tax breaks toward CE (e.g., the incentive for secondary resource markets). | - | ||

| - Certification, awards, and standards established to showcase sustainable material usage. | X | ||

| Promotion and Awareness | - Promote the use of sustainable and circular strategies | X | |

| - Inform citizens about the concept of the CE | - | ||

| Regulation | - Establish laws and policies toward sustainability and CE. | X | |

| - Create policy and legislation to integrate ecological and societal costs into the final price. | - | ||

| - Development of labeling standards that reflect the values of circularity. | - | ||

| Infrastructure | |||

| Available Infrastructure | - Effective collection and treatment of waste (e.g., recovery, transportation, storage, sorting waste). | X | [6,10,15,32,59,61] |

| - Guaranteed quantity and quality of the recycled materials. | X | ||

| - Geographical proximity | X | ||

| Technology | - Availability of technologies that facilitate recycling, optimization, or remanufacturing (e.g., more effective techniques to collect, separate, and recycle discarded materials). | X | |

| Economy and Competitive Markets | X | ||

| Capital and Funding | - Access to financial tools (e.g., private investors or international prize challenges). | X | [12,15,32,52,66,72,76,78,87,91] |

| Market Competition | - Respond to the emerging market (e.g., sustainable business growth to position themselves). | X | |

| - Support from demand network | |||

| Supply Chain | |||

| Leadership | - Change agents. Mobilizing actors in the material chain to set up circular initiatives. | X | [6,8,10,14,23,26,57,59,61,67,68,72,84,87,90,92] |

| Cooperation | - Collaboration along the supply chain. | X | |

| - Developing trust among the supply chain. | X | ||

| - Developing a business case that is acceptable for all the actors. | X | ||

| - Information exchange among different stakeholders (e.g., the industry). | - | ||

| Incentive to Suppliers | - Provide training and knowledge in regard to CE. | - | |

| - Create a reward program and exclusive partnerships with suppliers that are aligned with the company’s requirements. | - | ||

| Logistics | - Use of tools to facilitate product traceability in the supply chain. | - | |

| - Set up a reverse supply chain for the return of resources. | - | ||

| Type of Enabler | Associated Issues | Ref. | |

| Internal | |||

| Knowledge | |||

| Communication | - Availability of communications technologies (e.g., communication platforms). | X | [10,14,15,23,52,57,59,63,68,69,72,83,84,87,89] |

| Information and Awareness | - Developing knowledge (e.g., identification of suppliers with low environmental impact). | X | |

| - Digital intelligence (e.g., using IoT, Big Data, and have insight into all available data and use advanced data analytics). | X | ||

| - Clear communication on CE and its concept. | - | ||

| - Effective communication of CE success stories. | - | ||

| Information on CE | -Availability of information on CE (e.g., business model visualization tool). | - | |

| Financial | |||

| Financial Support | - Contractual agreements and/or alternative financing solutions such as crowdfunding. | - | [6,23,83,87] |

| - Access to finance. | X | ||

| Risk | - Conduct pilot programs to minimize risk. | X | |

| Organizational | |||

| Corporate Governance | - Creation of a new and independent business unit for cultural adaptation and sustainability principles. | - | [6,10,12,14,15,23,32,52,57,59,60,62,64,67,68,69,72,78,83,85,87] |

| - Support from the parent company. | - | ||

| Culture | - Internal collaboration. | X | |

| - Company culture (e.g., oriented toward environmental awareness). | X | ||

| Management | - Support and commitment from the top manager. | X | |

| - Strategic leadership for CE. | X | ||

| - System’s thinking approach for CE implementation. | - | ||

| - Acknowledgement of the problems of scarce resources and pollution. | X | ||

| Organizational Capabilities | - Specific training to develop new CE associated capabilities and skills. | - | |

| - Technical capacities and technical know-how (e.g., the use of by-products as inputs for other processes. | X | ||

| - Development of cross-functional capabilities through full integration of all functions and employees. | - | ||

| Organizational Resources | - Organizational resources (HR) (e.g., time and human). | X | |

| Strategies | - Outsourcing technical activities. | X | |

| - CE/Sustainability integrated into strategy, mission, vision, goals & KPI. | X | ||

| - Incentivize broad participation of employees. | - | ||

| - Create circular propositions based on the full lifecycle of the product. | X | ||

| - Lobbying (firms have a voice in helping to shape government policy). | X | ||

| - Demonstration of product reliability (e.g., offering innovative warranty options or offering ‘behind the curtain’ view of the firm’s processes). | X | ||

| Product and Material Characteristics | |||

| Design | - Redesign material for recycling, reuse, upgradability (e.g., use modular design). | X | [10,23,60,61,67,68,76,80] |

| - Reducing the impact of product obsolescence. | X | ||

| External Theoretical Categories | Empirical Barriers | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| User’s Behavior | ||

| Budget | - Users’ low ability to pay. Consumers are not able to afford sustainable goods. | “[T]here are people who tell us: ‘Hey, we like the bike, but it is costly do you sell other more affordable bamboo-items?” Company B |

| Preference and Demand | - Consumers’ skepticism. (e.g., Uncertainty about the product and little or no trust). | “[O]ur rental business model needed people who owned things, who buy them and do not use them (people would upload their things and provide the inventory for the platform). However, people were very skeptical... they did not see the advantage of renting their things. There was insecurity and fear among the people. Even though our repair-replace guarantees covered their products, they did not believe much in guarantees.” Company D |

| - People’s lack of familiarity with technologies. | “[T]here are people that fear online shopping… They rather go and buy the product at a physical store.” Company C | |

| Infrastructure | ||

| Infrastructure irregularities | - Lack of financial infrastructure (e.g., banking systems). | “Our biggest barrier was the entire financial part of how to transfer payments. We needed to freeze a “security deposit” amount that we refunded to the user after the rental. However, several banks did not want to accept the system.” Company D |

| - Lack of access to financial services, lack of financial inclusion. | “[W]e required a credit card to make the rent, but only a small fraction of the population has a credit card… there are few cards in circulation right now.” Company D | |

| Internal theoretical categories. | ||

| Knowledge | ||

| Information on CE | - Poor understanding of the CE concept (e.g., not systemic, focused on isolated practices, not measuring its impact). | - “[W]ell, we do not collaborate with our bamboo providers (to achieve CE initiatives) I do not have data on how the bamboo (for the bikes) is obtained.” Company B |

| External Theoretical Categories | Empirical Enablers | Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| User’s Behavior | ||

| Budget | - Tackle users’ ability to pay through inclusive business models (e.g., leasing or renting), making products both affordable and accessible. | “There are things that have to be rented and others that have to be bought… the social benefit was that renting customers did not have to spend much money to have access to a product…So, low-income people could access high-value products.” Company D |

| Preference and Demand | - Tackle users’ skepticism and lack of trust through a transparency strategy or the use of guarantees and certifications. | -“[W]e have a US certification that the bicycle works, of resistance… they (the consumers) trust a lot in the Americans.” Company B |

| - Tackle consumer’s reluctance to change by proposing an added-value business model. Consumers are likely to switch if the product is better at tackling their problem. | “[O]ur clients have the purchasing power to own a car, but they decide not to use it, or they could choose not to use it because they have a bicycle that can solve the city mobility problem.” Company B | |

| Infrastructure | ||

| Financial Infrastructure | - Use of supporting technologies that can be a substitute for the inadequate infrastructure (e.g., online payments). | “We could never get the banks to freeze the “security deposit” amount required for rental…we had to find a different method that could guarantee payment. Thus, we rely on electronic promissory note… to protect rental products from damage or theft.” Company D |

| “One of the enablers was the technology and access to information. We looked for solutions on the internet or learned from other people who were developing similar platforms. We used a lot of collaborative economy success stories, we saw and used new practices, new tools, new technology that we could use, and we started applying that.” Company D | ||

| Internal theoretical category | ||

| Organizational | ||

| OrganizationalCapabilities | - Learning process and adaptability. | “[L]earning to do it might be a barrier, but I do not see it as a barrier…. I see it as part of the process. Learn to implement the technologies that exist.” Company B |

| “The project was reinforced … it changed as it received more advice, as more things were experienced.” Company E | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cantú, A.; Aguiñaga, E.; Scheel, C. Learning from Failure and Success: The Challenges for Circular Economy Implementation in SMEs in an Emerging Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1529. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031529

Cantú A, Aguiñaga E, Scheel C. Learning from Failure and Success: The Challenges for Circular Economy Implementation in SMEs in an Emerging Economy. Sustainability. 2021; 13(3):1529. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031529

Chicago/Turabian StyleCantú, Andrea, Eduardo Aguiñaga, and Carlos Scheel. 2021. "Learning from Failure and Success: The Challenges for Circular Economy Implementation in SMEs in an Emerging Economy" Sustainability 13, no. 3: 1529. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031529

APA StyleCantú, A., Aguiñaga, E., & Scheel, C. (2021). Learning from Failure and Success: The Challenges for Circular Economy Implementation in SMEs in an Emerging Economy. Sustainability, 13(3), 1529. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031529