Manufacturer’s Sharing Servitization Transformation and Product Pricing Strategy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Model

3.1. Assumptions

3.2. Consumers’ Purchasing/Renting Decisions

4. Equilibrium Analysis

4.1. No Product Sharing for Manufacturer

4.2. Product Sharing for Manufacturer

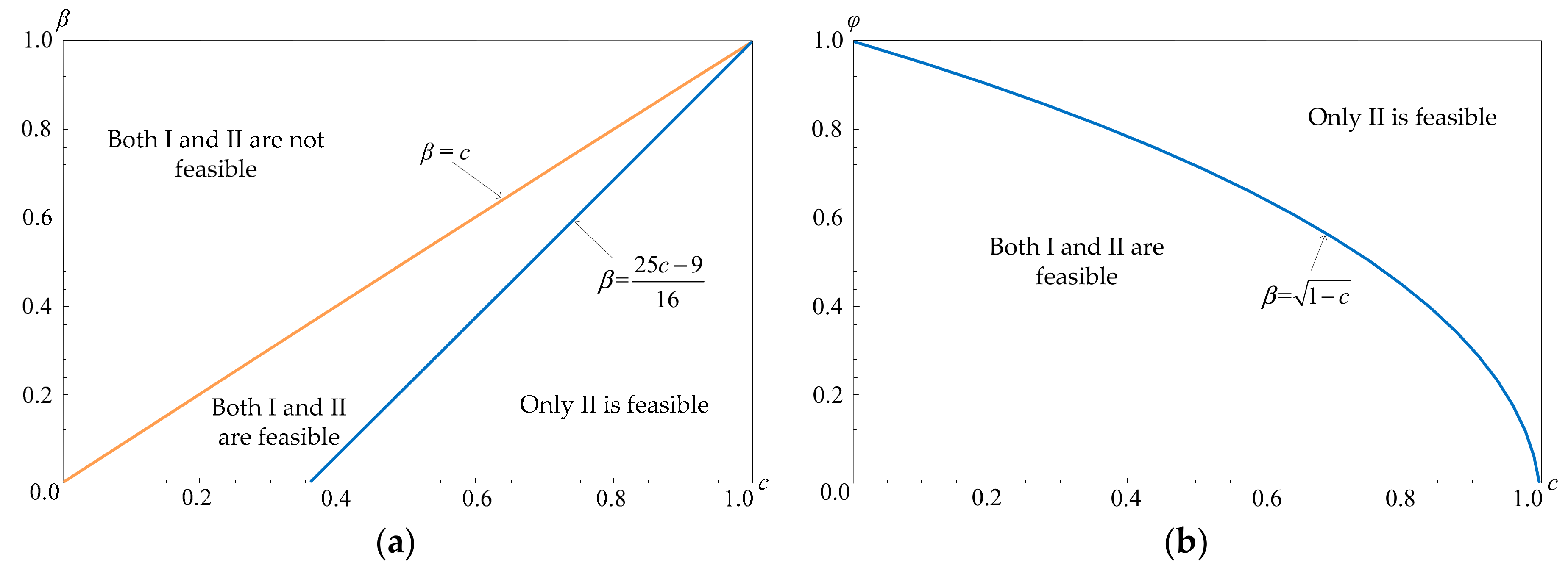

4.3. Main Results

- (1)

- Only ifanddo consumers purchase new products in the sales market or rent idle products in the sharing market.

- (2)

- Ifand, consumers only rent idle products in the sharing market, but the manufacturer withdraws from the sales market.

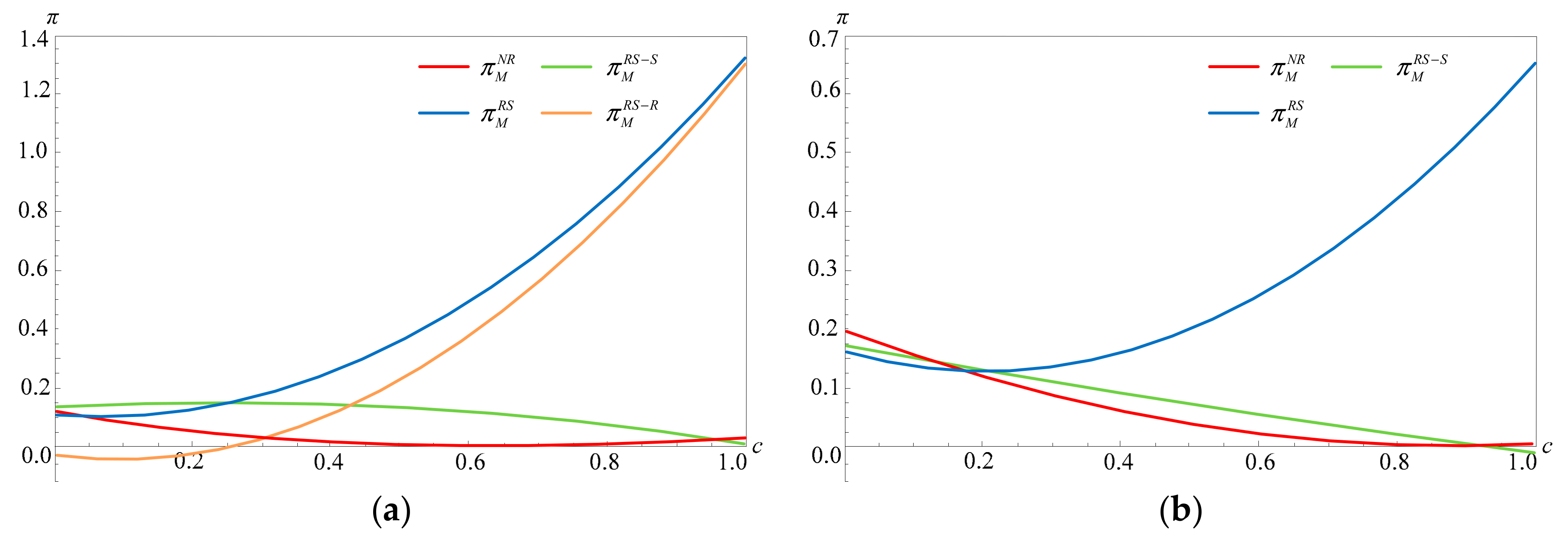

4.4. Numerical Analysis

4.5. Special Scenario for the Pandemic

5. Discussion and Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- PwC. “The Sharing Economy.” PwC Consumer Intelligence Series. 2015. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/us/en/technology/publications/assets/pwc-consumer-intelligence-series-the-sharing-economy.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- PwC. Share Economy 2017: The New Business Model. 2018. Available online: https://www.pwc.de/share-economy (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Feng, J.; Liu, B.; Liu, Z. Manufacturer’s business strategy: Interaction of sharing economy and product rollover. Complexity 2020, 3, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- iiMedia Research. 2018–2019 China Shared Economy Industry Panorama Research Report. 2019. Available online: https://www.iimedia.cn/c400/66502.html (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Li, F. Daimler Pulls Plug on Car-Sharing Program. Available online: https://global.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201906/03/WS5cf49491a310a4317f1d8073.html (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- SHARE NOW. Service Ending February 29th. Available online: https://www.share-now.com/ca/en/important-update/ (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Brown, L.S. GM’s Car-Sharing Service, Maven, Shuts Down after Four Years. Available online: https://www.caranddriver.com/news/a32235218/gm-maven-car-sharing-closes/ (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Hossain, M. The effect of the Covid-19 on sharing economy activities. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D. Pandemic Hinders Growth of Car-Sharing Business. Available online: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202007/13/WS5f0bc279a310834817258f3b.html (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Belk, R. You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 1595–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plewnia, F.; Guenther, E. Mapping the sharing economy for sustainability research. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 570–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurenti, R.; Singh, J.; Cotrim, J.M.O.; Toni, M.; Sinha, R. Characterizing the sharing economy state of the research: A systematic map. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hossain, M. Sharing economy: A comprehensive literature review. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbari, M.; Morales-Alonso, G.; Carrasco-Gallego, R. Conceptualizing the sharing economy through presenting a comprehensive framework. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, J.; Lv, X. Feeling dark, seeing dark: Mind–body in dark tourism. Ann. Tourism Res. 2021, 86, 103087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Xiao, N.; Xu, F.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, K.; Ye, C. An equivalent exchange based data forwarding incentive scheme for socially aware networks. J. Signal Processi. Syst. 2020, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurell, C.; Sandström, C. Comparing coverage of disruptive change in social and traditional media: Evidence from the sharing economy. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 129, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Li, H.; Xia, L. Effects of haptic cues on consumers’ online hotel booking decisions: The mediating role of mental imagery. Tourism Manage. 2020, 77, 104025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Liu, Y.; Luo, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, C. Does a cute artificial intelligence assistant soften the blow? The impact of cuteness on customer tolerance of assistant service failure. Ann. Tourism Res. 2021, 87, 103114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraiberger, S.P.; Sundararajan, A. Peer-to-peer rental markets in the sharing economy. Work. Paper 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fradkin, A. Search, matching, and the role of digital marketplace design in enabling trade: Evidence from Airbnb. Work. Paper 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benjaafar, S.; Kong, G.; Li, X.; Courcoubetis, C. Peer-to-peer product sharing: Implications for ownership, usage, and social welfare in the sharing economy. Manag. Sci. 2018, 65, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abhishek, V.; Guajardo, J.; Zhang, Z. Business Models in the Sharing Economy: Manufacturing Durable Goods in the Presence of Peer-to-Peer Rental Markets. 2020. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2891908 (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- Jiang, B.; Tian, L. Collaborative consumption: Strategic and economic implications of product sharing. Manag. Sci. 2018, 64, 1171–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Jiang, B. Effects of consumer-to-consumer product sharing on distribution channel. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2018, 27, 350–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Feng, J.; Wang, J. Effects of the sharing economy on sequential innovation products. Complexity 2019, 2019, 3089641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, H.; Chai, S.; Cheng, R. Selling or sharing: Business model selection problem for an automobile manufacturer with uncertain information. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2018, 36, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razeghian, M.; Weber, T.A. The advent of the sharing culture and its effect on product pricing. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2019, 33, 100801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Tian, L.; Xu, Y. Manufacturer’s entry in the product-sharing market. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nishino, N.; Takenaka, T.; Takahashi, H. Manufacturer’s strategy in a sharing economy. CIRP Ann. 2017, 1, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, T.A. Product pricing in a peer-to-peer economy. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2016, 33, 573–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmidt, P. The effect of car sharing on car sales. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2020, 71, 102622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Bai, X.; Xue, K. Business modes in the sharing economy: How does the OEM cooperate with third-party sharing platforms? Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 221, 107467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chardon, C.M.; Caruso, G.; Thomas, I. Bicycle sharing system ‘success’ determinants. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017, 100, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabra, A.; Belavina, E.; Girotra, K. Bike-share systems: Accessibility and availability. Work. Paper 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bellos, I.; Ferguson, M.; Toktay, L.B. The car sharing economy: Interaction of business model choice and product line design. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2017, 19, 185–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, T.A. Intermediation in a sharing economy: Insurance, moral hazard, and rent extraction. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2014, 31, 35–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Feng, J.; Liu, B. Pricing and Service Level Decisions under a Sharing Product and Consumers’ Variety-Seeking Behavior. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, J.; Shi, Q.; Wu, P.; Sheng, Z.; Wang, X. Complexity analysis of prefabrication contractors’ dynamic price competition in mega projects with different competition strategies. Complexity 2018, 5928235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Han, Y.; Wu, Z.; Raza, H. Consensus modeling with asymmetric cost based on data-driven robust optimization. Group Decis. Negot. 2020, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L. Changing port governance model: Port spatial structure and trade efficiency. J. Coastal Res. 2020, 95(S1), 963–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Q. Pricing decisions and innovation strategies choice in supply chain with competing manufacturers and common supplier. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ye, Y.; Ma, J.; Shi, P.; Chen, H. Construction of electric vehicle driving cycle for studying electric vehicle energy consumption and equivalent emissions. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2020, 27, 37395–37409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucsky, P. Modal share changes due to COVID-19: The case of Budapest. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 8, 100141. [Google Scholar]

- Aurora Mobile. Report on the Development Trend of Car-Sharing in 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.jiguang.cn/reports/494 (accessed on 15 December 2020).

| i | ith Consumer, i = 1, 2, 3… |

| j | Products, j = B (buying a new product from manufacturer), 1 (renting product from manufacturer), 2 (renting product from the owner). |

| Vi | ith consumer’s valuation for purchasing/renting product, vi~U [0, 1]. |

| ui,j | ith consumer’s utility of choosing product j. |

| pj | Price of product j. |

| ηj | Consumer’s preference for sharing product. |

| dj | The demand for product j. |

| c | Product’s production cost. |

| α | The transaction cost of sharing product’s in B2C sharing market. |

| g | The operation cost of sharing product’s in B2C sharing market. |

| β | The transaction cost of sharing product’s in C2C platform. |

| φ | Sharing a product’s availability rate, φ∈[0, 1]. |

| S(φ) | The number of sharing products from the manufacturer. |

| πM | The manufacturer’s total profit. |

| πO | Owner’s earnings. |

| NR | The manufacturer does not enter the sharing market, denoted as a superscript NR. |

| RS | Manufacturer enters the sharing market, denoted as a superscript RS. |

| -S | Sales market, denoted as a superscript -S. |

| -R | Sharing market, denoted as a superscript -R. |

| C | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| φ = 0.9, β = 0.5c | 0.3 | 0.426 | 0.458 | 0.288 | 0.231 | 0.430 | - | 0.932 | 1.244 | 0.205 | 0.658 | 0.175 | - | 0.147 | 0.035 | 0.029 | 0.124 |

| 0.5 | 0.616 | 0.626 | 0.438 | 0.339 | 0.556 | 0.07 | 1.139 | 1.690 | 0.008 | 0.810 | 0.360 | 0.228 | 0.132 | 0.006 | 0.035 | 0.229 | |

| 0.8 | 0.852 | 0.924 | 0.662 | 0.500 | 0.744 | 0.045 | 1.449 | 2.360 | - | 1.038 | 0.851 | 0.775 | 0.076 | - | 0.044 | 0.446 | |

| φ = 0.6, β = 0.5c | 0.3 | 0.407 | 0.509 | 0.279 | 0.286 | 0.552 | - | 0.505 | 1.159 | 0.310 | 0.489 | 0.127 | - | 0.106 | 0.083 | 0.018 | 0.040 |

| 0.5 | 0.597 | 0.641 | 0.423 | 0.390 | 0.664 | - | 0.487 | 1.560 | 0.183 | 0.568 | 0.191 | - | 0.069 | 0.035 | 0.018 | 0.065 | |

| 0.8 | 0.880 | 0.839 | 0.640 | 0.546 | 0.831 | - | 0.460 | 2.162 | - | 0.687 | 0.408 | - | 0.018 | - | 0.018 | 0.113 |

| c | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| φ = 0.9, β = 0.5c | 0.3 | 0.426 | 0.458 | 0.288 | 0.231 | 0.430 | - | 0.932 | 1.244 | 0.205 | 0.658 | 0.175 | - | 0.147 | 0.035 | 0.029 | 0.124 |

| 0.5 | 0.616 | 0. 626 | 0.438 | 0.339 | 0.556 | 0.07 | 1.139 | 1.690 | 0.008 | 0.810 | 0.360 | 0.228 | 0.132 | 0.006 | 0.035 | 0.229 | |

| 0.8 | 0.852 | 0. 924 | 0.662 | 0.500 | 0.744 | 0.045 | 1.449 | 2.360 | - | 1.038 | 0.851 | 0.775 | 0.076 | - | 0.044 | 0.446 | |

| φ = 0.9, β = 0.6c | 0.3 | 0.479 | 0.542 | 0.329 | 0.312 | 0.567 | - | 0.512 | 0.906 | 0.316 | 0.474 | 0.129 | - | 0.128 | 0.089 | 0.024 | 0.062 |

| 0.5 | 0. 675 | 0.681 | 0.490 | 0.431 | 0.679 | - | 0.490 | 1.159 | 0.193 | 0.549 | 0.165 | - | 0.091 | 0.040 | 0.025 | 0.101 | |

| 0.8 | 0.873 | 0.984 | 0.732 | 0.607 | 0.847 | - | 0.460 | 1.539 | 0.009 | 0.661 | 0.316 | - | 0.037 | 0.010 | 0.027 | 0.178 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Feng, J. Manufacturer’s Sharing Servitization Transformation and Product Pricing Strategy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1503. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031503

Liu Z, Xiao Y, Feng J. Manufacturer’s Sharing Servitization Transformation and Product Pricing Strategy. Sustainability. 2021; 13(3):1503. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031503

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Zhenfeng, Ya Xiao, and Jian Feng. 2021. "Manufacturer’s Sharing Servitization Transformation and Product Pricing Strategy" Sustainability 13, no. 3: 1503. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031503