Between Village and Town: Small-Town Urbanism in Sub-Saharan Africa

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Small-Town Urbanism

3. Materials and Methods

4. Economic, Material and Social Dimensions of Small Town Urbanization

4.1. Livelihoods in-Between

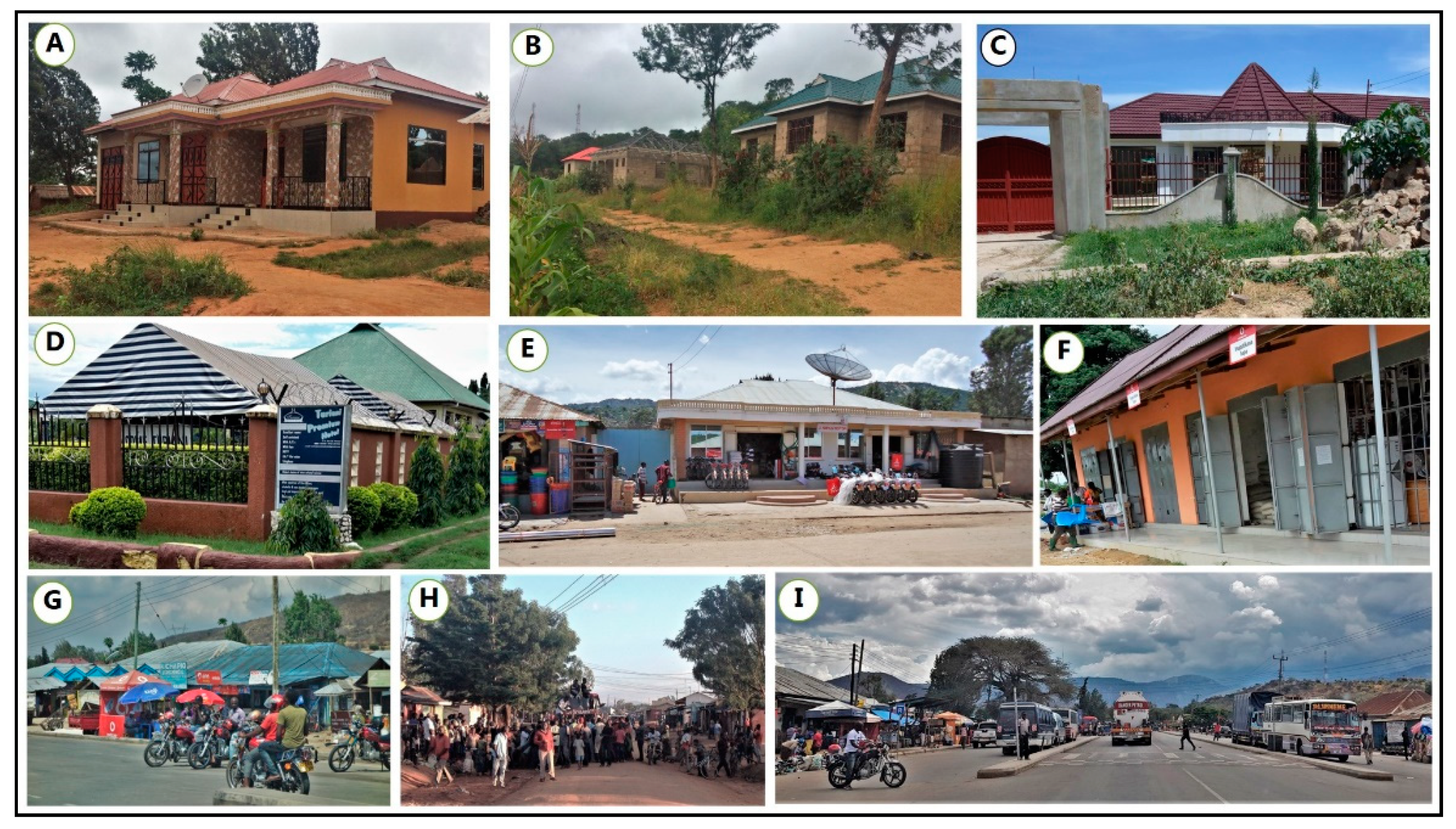

4.2. Material Dimensions of Urbanism

4.3. Aspirations for Urban Living

5. Urbanism between Village and Town

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- United Nations; Department of Economic and Social Affairs; Population Division. World Population Prospects Highlights, 2019 Revision Highlights, 2019 Revision; Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-92-1-148316-1. [Google Scholar]

- Angel, S. Making Room for a Planet of Cities. In The City Reader, 7th ed.; Routledge Urban Reader Series; LeGates, R.T., Stout, F., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 665–677. ISBN 978-0-429-26173-2. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The World’s Cities in 2016; Statistical Papers—United Nations (Series A), Population and Vital Statistics Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-92-1-362000-7. [Google Scholar]

- OECD; Sahel and West Africa Club. Africa’s Urbanisation Dynamics 2020: Africapolis, Mapping a New Urban Geography; West African Studies; OECD: Paris, France, 2020; ISBN 978-92-64-57958-3. [Google Scholar]

- UCLG. Fourth Global Report on Decentralization and Local Democracy. Co-Creating the Urban Future: The Agenda of Metropolises, Cities and Territories; United Cities and Local Governments: Barcelona, Spain, 2017.

- Curiel, R.P.; Heinrigs, P.; Heo, I. Cities and Spatial Interactions in West Africa; OECD: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Denis, E.; Zérah, M.-H. Subaltern Urbanisation in India: An Introduction to the Dynamics of Ordinary Towns; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2017; ISBN 81-322-3616-5. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, V. Locating planning in the New Urban Agenda of the urban sustainable development goal. Plan. Theory 2016, 15, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, S. Towards a paradigm of Southern urbanism. City 2017, 21, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vliet, J.; Birch-Thomsen, T.; Gallardo, M.; Hemerijckx, L.-M.; Hersperger, A.M.; Li, M.; Tumwesigye, S.; Twongyirwe, R.; van Rompaey, A. Bridging the rural-urban dichotomy in land use science. J. Land Use Sci. 2020, 15, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derickson, K.D. Urban geography I: Locating urban theory in the ‘urban age’. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2015, 39, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N. New Urban Spaces: Urban Theory and the Scale Question; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-0-19-062721-8. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, N.; Schmid, C. Towards a new epistemology of the urban? City 2015, 19, 151–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, E. Grasping the unknowable: Coming to grips with African urbanisms. Soc. Dyn. 2011, 37, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieterse, E. Introduction: Rogue urbanisms. Soc. Dyn. 2011, 37, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.; Jayne, M. Small Cities? Towards a Research Agenda. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2009, 33, 683–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacour, C.; Puissant, S. Re-Urbanity: Urbanising the Rural and Ruralising the Urban. Environ. Plan A 2007, 39, 728–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiaensen, L.; De Weerdt, J.; Kanbur, R. Urbanization and Poverty Reduction: The Role of Secondary Towns in Tanzania; Universiteit Antwerpen, Institute of Development Policy and Management (IOB): Antwerpen, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bryceson, D.F. Birth of a market town in Tanzania: Towards narrative studies of urban Africa. J. East. Afr. Stud. 2011, 5, 274–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Weerdt, J. Moving out of poverty in Tanzania: Evidence from Kagera. J. Dev. Stud. 2010, 46, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottyn, I. Between Modern Urbanism and “Rural” Realities: Rwanda’s Changing Rural-Urban Interface and the Implications for Inclusive Development. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Steel, G.; Birch-Thomsen, T.; Cottyn, I.; Lazaro, E.A.; Mainet, H.; Mishili, F.J.; van Lindert, P. Multi-activity, multi-locality and small-town development in Cameroon, Ghana, Rwanda and Tanzania. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2019, 31, 12–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agergaard, J.; Tacoli, C.; Steel, G.; Ørtenblad, S.B. Revisiting Rural–Urban Transformations and Small Town Development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2019, 31, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I.; Murimbarimba, F. Small towns and land reform in Zimbabwe. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2020. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tacoli, C.; Agergaard, J. Urbanisation, Rural Transformation and Food Systems: The Role of Small Towns; Working Paper: Rural-Urban Transformation and Food Systems; IIED: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, M.N.; Birch-Thomsen, T. The role of credit facilities and investment practices in rural Tanzania: A comparative study of Igowole and Ilula emerging urban centres. J. East. Afr. Stud. 2015, 9, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazaro, E.; Agergaard, J.; Larsen, M.N.; Makindara, J.; Birch-Thomsen, T. Rural Transformation and the Emergence of Urban Centres in Tanzania; Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management, University of Copenhagen: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017; p. 35. [Google Scholar]

- Lazaro, E.; Agergaard, J.; Larsen, M.N.; Makindara, J.; Birch-Thomsen, T. Urbanisation in Rural Regions: The Emergence of Urban Centres in Tanzania. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2019, 31, 72–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Campos, J.; Naxhelli, R. Rurbanization in the Regional Periphery of Central Mexico. In Human Settlement Development; EOLSS Publishers/UNESCO: Paris, France, 2009; ISBN 978-1-84826-045-0. [Google Scholar]

- Guin, D. From Large Villages to Small Towns: A Study of Rural Transformation in New Census Towns, India. Int. J. Rural Manag. 2018, 14, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, L.E.; Bruns, A.; Simon, D. Towards Situated Analyses of Uneven Peri-Urbanisation: An (Urban) Political Ecology Perspective. Antipode 2020, 52, 1237–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, R. After Suburbia: Research and action in the suburban century. Urban Geogr. 2020, 41, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, T. The Spatiality of Urbanization: The Policy Challenges of Mega-Urban and Desakota Regions of Southeast Asia; United Nations University: Tokyo, Japan, 2009; p. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Vidovich, L.D. Suburban studies: State of the field and unsolved knots. Geogr. Compass 2019, 13, e12440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiaensen, L.; Todo, Y. Poverty Reduction During the Rural–Urban Transformation—The Role of the Missing Middle. World Dev. 2014, 63, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterthwaite, D. Outside the Large Cities; The Demographic Importance of Small Urban Centres and Large Villages in Africa, Asia and Latin America; IIED: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tacoli, C. Urbanisation and migration in Sub-Saharan Africa: Changing patterns and trends. In Mobile Africa: Changing Patterns of Movement in Africa and Beyond; De Bruijn, M., van Dijk, R., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 141–152. [Google Scholar]

- Tacoli, C. The Earthscan Reader in Rural-Urban Linkages; Earthscan: London, UK, 2006; ISBN 1-84407-316-5. [Google Scholar]

- Cottyn, I. Small towns and rural growth centers as strategic spaces of control in Rwanda’s post-conflict trajectory. J. East. Afr. Stud. 2018, 12, 329–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J. State, Governance and the Creation of Small Towns in Ethiopia. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2019, 31, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacoli, C. The links between urban and rural development. Environ. Urban. 2003, 15, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryceson, D.F. Deagrarianization and rural employment in sub-Saharan Africa: A sectoral perspective. World Dev. 1996, 24, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryceson, D.F. African rural labour, income diversification & livelihood approaches: A long-term development perspective. Rev. Afr. Political Econ. 1999, 26, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, G.; van Lindert, P. Rural Livelihood Transformations and Local Development in Cameroon, Ghana and Tanzania; Working Paper: Rural-Urban Transformation and Food Systems; IIED: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zoomers, A. Globalisation and the foreignisation of space: Seven processes driving the current global land grab. J. Peasant Stud. 2010, 37, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigg, J. An Everyday Geography of the Global South; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, P.F. Migration, Agrarian Transition, and Rural Change in Southeast Asia. Crit. Asian Stud. 2011, 43, 479–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, C.; Page, B.; Evans, M. Development and the African Diaspora; Zed Books: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zoomers, A.; Leung, M.; van Westen, G. Local Development in the Context of Global Migration and the Global Land Rush: The Need for a Conceptual Update. Geogr. Compass 2016, 10, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, B.; Sunjo, E. Africa’s middle class: Building houses and constructing identities in the small town of Buea, Cameroon. Urban Geogr. 2018, 39, 75–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Brauw, A.; Mueller, V.; Lee, H.L. The Role of Rural–Urban Migration in the Structural Transformation of Sub-Saharan Africa. World Dev. 2014, 63, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaag, M.; Baltissen, G.; Steel, G.; Lodder, A. Migration, Youth, and Land in West Africa: Making the Connections Work for Inclusive Development. Land 2019, 8, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ørtenblad, S.B.; Birch-Thomsen, T.; Msese, L.R. Rural Transformation and Changing Rural-Urban Connections in a Dynamic Region in Tanzania: Perspectives on Processes of Inclusive Development. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2019, 31, 118–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wineman, A.; Liverpool-Tasie, L.S. Land markets and migration trends in Tanzania: A qualitative-quantitative analysis. Dev. Policy Rev. 2018, 36, O831–O856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijenhuis, K. Farmers on the Move: Mobility, Access to Land and Conflict in Central and South Mali. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University & Research, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Büscher, K.; Mathys, G. War, Displacement and Rural-Urban Transformation: Kivu’s Boomtowns, Eastern D.R. Congo. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2019, 31, 53–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathys, G.; Büscher, K. Urbanizing Kitchanga: Spatial trajectories of the politics of refuge in North Kivu, Eastern Congo. J. East. Afr. Stud. 2018, 12, 232–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, M. Infrastructural Hope: Anticipating ‘Independent Roads’ and Territorial Integrity in Southern Kyrgyzstan. Ethnos 2017, 82, 711–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D. Uncertain times, contested resources: Discursive practices and lived realities in African urban environments. City 2015, 19, 216–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anh, N.T.; Rigg, J.; Huong, L.T.T.; Dieu, D.T. Becoming and being urban in Hanoi: Rural-urban migration and relations in Viet Nam. J. Peasant Stud. 2012, 39, 1103–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockx, L.; Colen, L.; De Weerdt, J. From corn to popcorn? Urbanization and dietary change: Evidence from rural-urban migrants in Tanzania. World Dev. 2018, 110, 140–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worrall, L.; Colenbrander, S.; Palmer, I.; Makene, F.; Mushi, D.; Kida, T.; Martine, M.; Godfrey, N. Better Urban Growth in Tanzania: Preliminary Exploration of the Opportunities and Challenges; Coalition for Urban Transitions: London, UK; Washington, DC, USA, 2017; p. 90. [Google Scholar]

- Kironyi, L. The Role of Governance Structures and Practices Related to Land, Water and Waste in Supporting Transformation of Ilula and Madizini Emerging Urban Centres, Tanzania. Ph.D. Thesis, Sokoine University, Morogoro, Tanzania, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nyaki, S.A. Business Development and the Role of Social Networks in Business Investment and Employment Creation in Tanzania’s Emerging Urban Centres. Ph.D. Thesis, Sokoine University, Morogoro, Tanzania, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- NBS. Tanzania Population and Housing Census: Population Distribution by Administrative Areas; National Bureau of Statistics: Dodoma, Tanzania, 2013.

- Beckham, S.W.; Shembilu, C.R.; Winch, P.J.; Beyrer, C.; Kerrigan, D.L. ‘If you have children, you have responsibilities’: Motherhood, sex work and HIV in southern Tanzania. Cult. Health Sex. 2015, 17, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folkers, A.S.; van Buiten, B.A.C. Turiani Hospital. In Modern Architecture in Africa: Practical Encounters with Intricate African Modernity; Folkers, A.S., van Buiten, B.A.C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 248–258. ISBN 978-3-030-01075-1. [Google Scholar]

- Burchardt, M. Belonging and Success: Religious Vitality and the Politics of Urban Space in Cape Town; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 167–187. ISBN 978-90-04-24907-3. [Google Scholar]

- Wenban-Smith, H. Population Growth, Internal Migration, and Urbanisation in Tanzania, 1967–2012; Working Paper; International Growth Centre, London School of Economics: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mayaki, I.A. Comment to the SWAC/OECD Report. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/africa-urbanisation/#policy-makers (accessed on 10 January 2021).

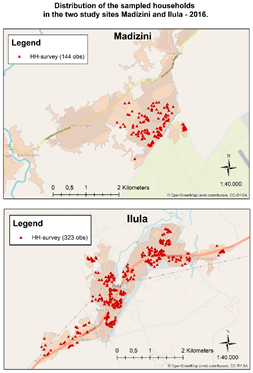

| Madizini | Ilula | |

|---|---|---|

| Estimated population | 14,168 (2012) | 22,957 (2012) |

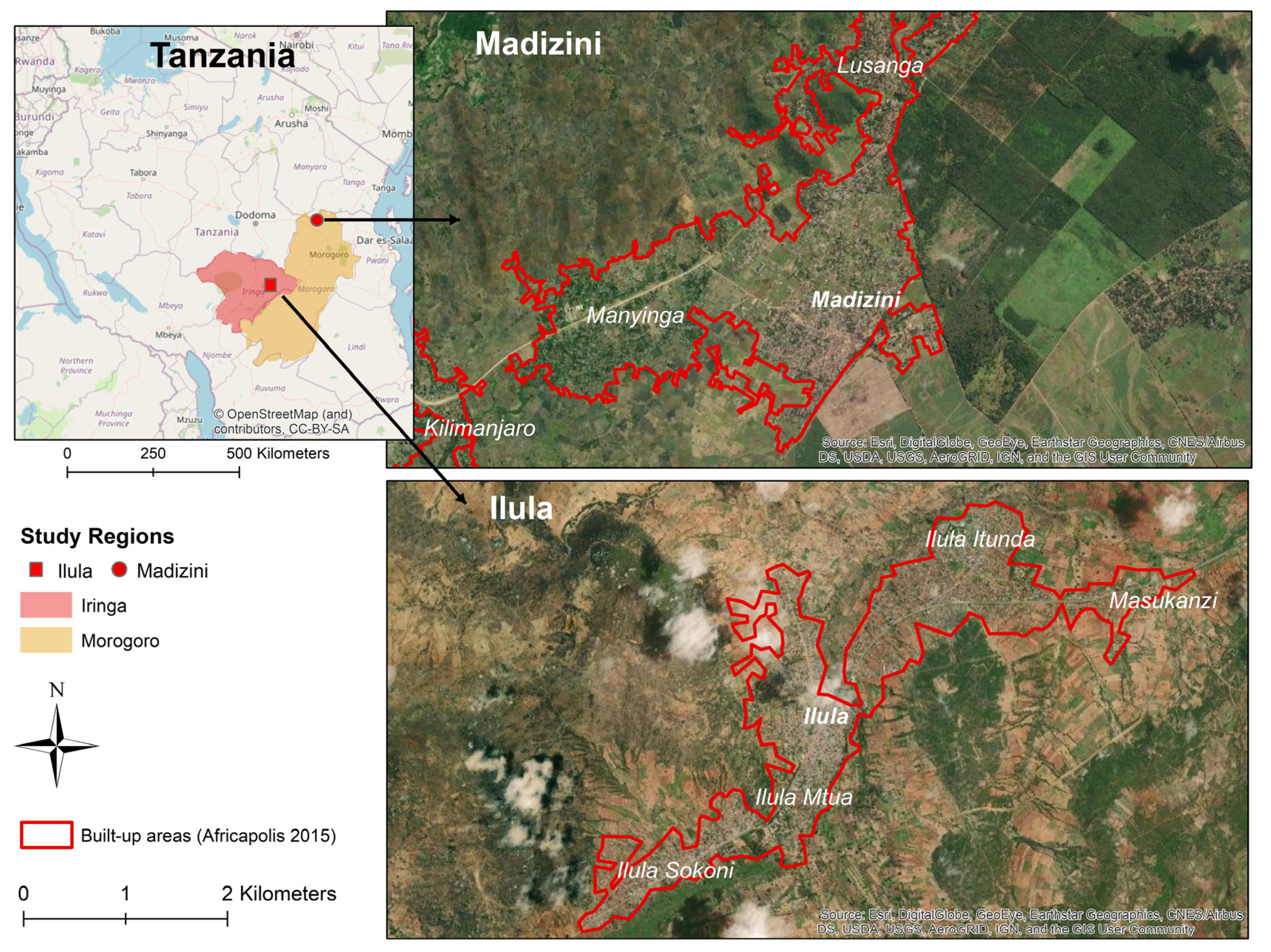

| Geographical location | Located on rich and predominantly rain-fed agricultural land | Located amidst large land tracts, huge variation in land quality |

| Infrastructural location | Until recently located off the road system. Approximately 100 km north of Morogoro Town (regional headquarters) | Located on the TanZam (Tanzania-Zambia) highway. Approximately 50 km south of Iringa Town (regional headquarter) |

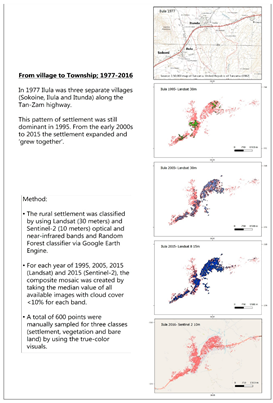

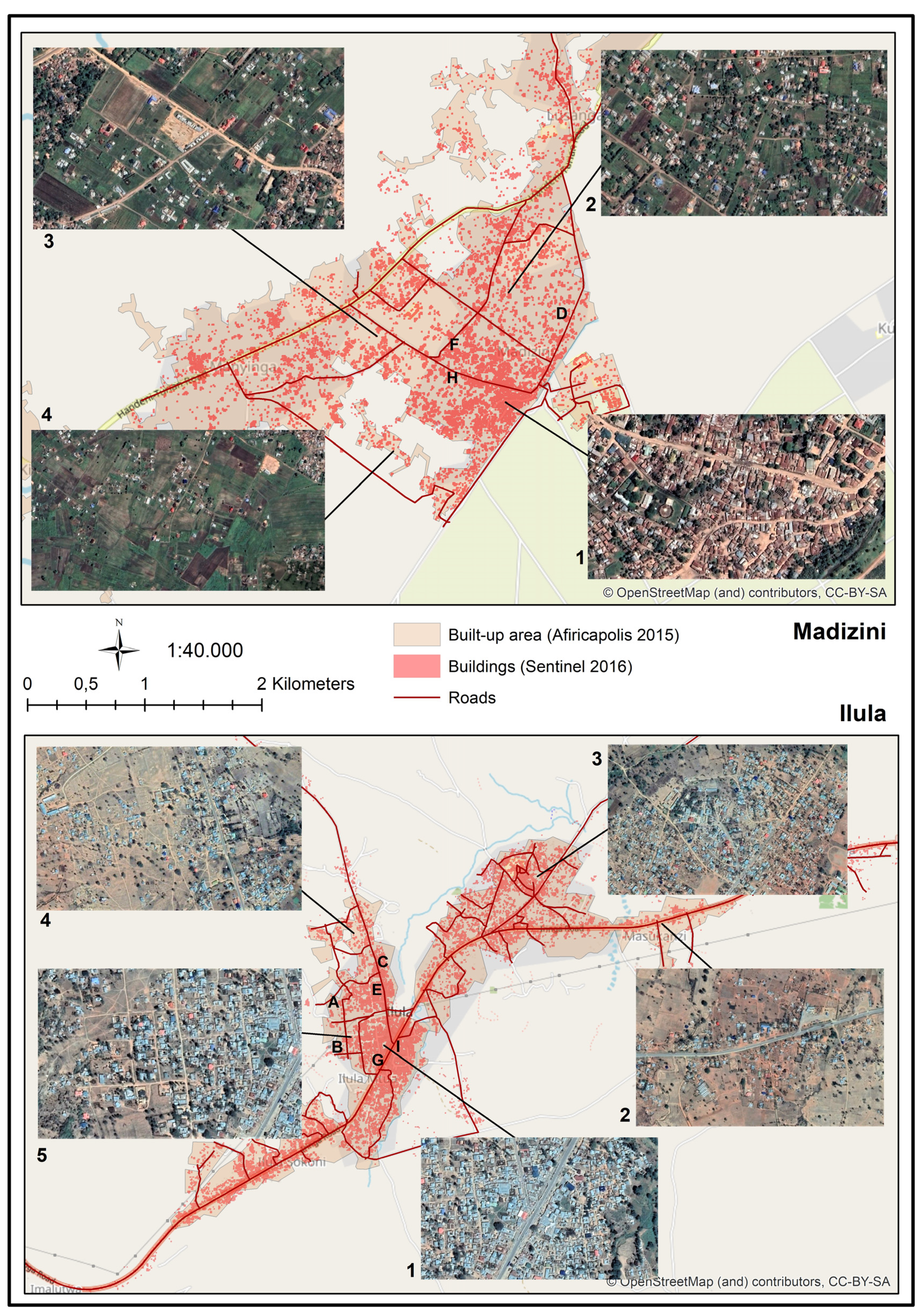

| Physical expansion | Mushrooming from the small village around the old factory, recently eating up the open space between neighbouring villages | Agglomerating town: open spaces between villages have continuously been transformed into build-up land |

| Densification | High density radiating from the early ‘urban’ centre | Medium density–more ‘urban’ centres |

| Initial drivers of growth | Sugar cane plantation, factory and out grower scheme | Transport corridor, tomato production and tomato market (religious centre) |

| New drivers of growth | Tree factory, dairy farming, businesses and local service centre functions | Tomato factory, ‘road stop economy’, businesses and local service centre functions |

| Administrative transformation | Township status announced in 2002. Very slow transformation towards township (urban) status, reluctance of district authorities to devolve line offices, resources etc. | Township status announced in 2006. Slow transformation towards township (urban) status, recently the district has agreed to support the establishment of some formal structures |

| Main Occupation | Madizini (n = 143) | Ilula (n = 323) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage | Locals (No.) | Migrants (No.) Mean Year of Arrival | Percentage | Locals (No.) | Migrants (No.) Mean Year of Arrival | |

| Agriculture | 49 | 12 | 57 1996 | 70 | 120 | 105 1998 |

| Business | 21 | 5 | 25 2003 | 11 | 15 | 20 2005 |

| Government | 5 | 1 | 6 2003 | 5 | 5 | 12 1999 |

| Other jobs | 22 | 5 | 27 2000 | 11 | 19 | 16 2006 |

| Other | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 5 |

| Total | 100 | 24 (17%) | 119 (83%) | 100 | 165 (51%) | 158 (49%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Agergaard, J.; Kirkegaard, S.; Birch-Thomsen, T. Between Village and Town: Small-Town Urbanism in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1417. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031417

Agergaard J, Kirkegaard S, Birch-Thomsen T. Between Village and Town: Small-Town Urbanism in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability. 2021; 13(3):1417. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031417

Chicago/Turabian StyleAgergaard, Jytte, Susanne Kirkegaard, and Torben Birch-Thomsen. 2021. "Between Village and Town: Small-Town Urbanism in Sub-Saharan Africa" Sustainability 13, no. 3: 1417. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031417

APA StyleAgergaard, J., Kirkegaard, S., & Birch-Thomsen, T. (2021). Between Village and Town: Small-Town Urbanism in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainability, 13(3), 1417. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031417