Toward Cultural Heritage Sustainability through Participatory Planning Based on Investigation of the Value Perceptions and Preservation Attitudes: Qing Mu Chuan, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

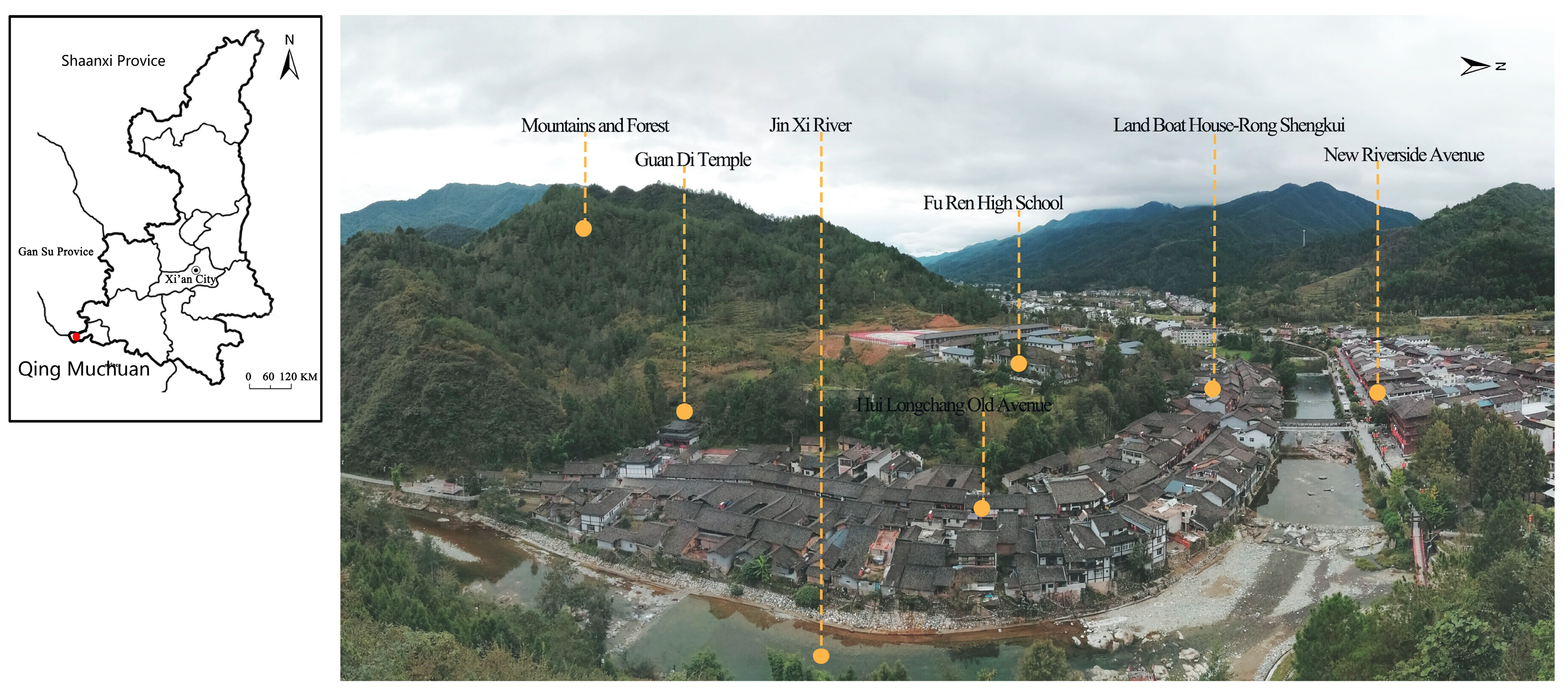

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Survey Instrument

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Processing

3. Results

3.1. The Preferences, Value Perceptions, and Preservation Willingness of the Respondents toward the Landscapes of the Traditional Village of Qing Mu Chuan

3.2. Differences in the Landscape Preferences, Value Perceptions, and Preservation Attitudes toward the Landscapes of the Traditional Village of Qing Mu Chuan between the Local Residents and Landscape Professionals

3.3. Correlations between the Value Perceptions and Preservation Attitudes

4. Discussion

4.1. Differences in the Traditional Village Landscape Preferences, Value Perceptions, and Preservation Attitudes between Local Residents and Landscape Professionals in Rural China

4.2. Correlations between the Value Perceptions and Preservation Attitudes

4.3. Suggestions for Participatory Conservation Planning to Achieve Cultural Heritage Sustainability

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

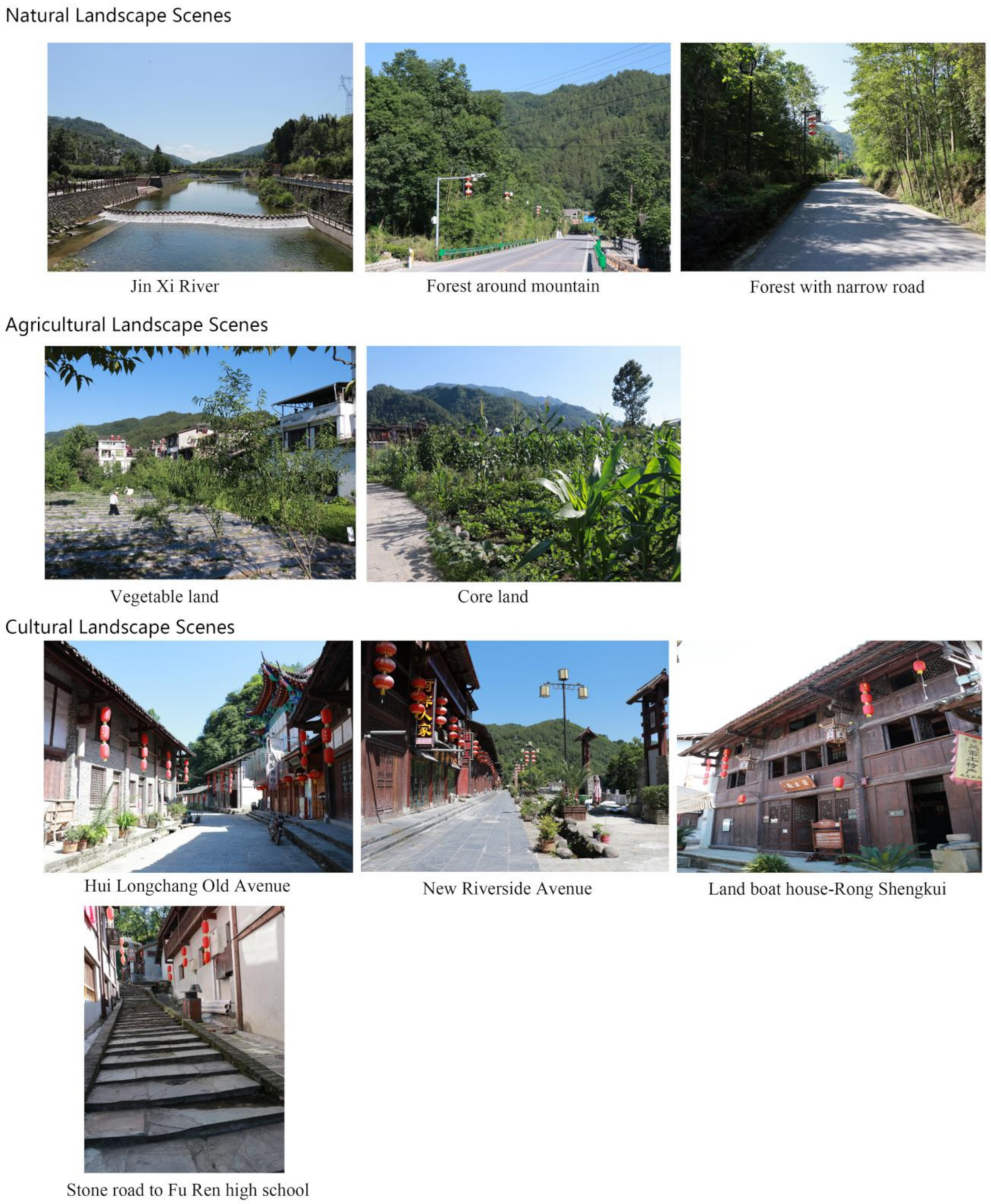

Appendix A. The Landscape Scenes Selected for Analysis

References

- World Heritage List: Does it make sense? Int. J. Cult. Policy 2011, 17, 555–573. [CrossRef]

- Nocca, F. The Role of Cultural Heritage in Sustainable Development: Multidimensional Indicators as Decision-Making Tool. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015.

- United Nations. Draft Outcome Document of the United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III); United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nurse, K. Culture as the fourth pillar of sustainable development. In Small States: Economic Review and Basic Statistics; The Commonwealth Secretariat: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. The ICOMOS Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas. 1987. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters/towns_e.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- ICOMOS. Burra Charter. 1999. Available online: https://australia.icomos.org/publications/charters/ (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Kahila-Tani, M.; Kyttä, M.; Geertman, S. Does mapping improve public participation? Exploring the pros and cons of using public participation GIS in urban planning practices. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 186, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, A. Public participation in cultural resource management: A Canadian perspective. In ICOMOS General Assembly Entitled “Patrimonio y Conservación: Arqueología. XII Asamblea General del ICOMOS”; INAH: Mexico City, Mexico, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, P. Diverging attitudes of planners and the public: An examination of architectural interpretation. J. Arch. Plan. Res. 1997, 14, 317–328. [Google Scholar]

- Appleton, J. The Experience of Landscape; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S.; Kaplan, R. Humanscape: Environments for People; Duxbury Press: Belmont, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Orians, G.H. Habitat selection: General theory and applications to human behavior. In The Evolution of Human Social Behavior; Lockard, J.S., Ed.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 1980; pp. 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, R.S. Biophilia, biophobia, and natural landscapes. In The Biophilia Hypothesis; Kellert, S.R., Wilson, E.O., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; pp. 73–137. [Google Scholar]

- Howley, P.; O’Donoghue, C.; Hynes, S. Exploring public preferences for traditional farming landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 104, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K. Cultural variations in landscape preference: Comparisons among Chinese sub-groups and Western design experts. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 32, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natori, Y.; Chenoweth, R. Differences in rural landscape perceptions and preferences between local residents and naturalists. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 250–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunziker, M.; Felber, P.; Gehring, K.; Buchecker, M. Evaluation of landscape change by different social groups: Results of two empirical studies in Switzerland. Mt. Res. Dev. 2008, 28, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppakittpaisarn, P.; Larsen, L.; Sullivan, W.C. Preferences for green infrastructure and green stormwater infrastructure in urban landscapes: Differences between designers and laypeople. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 43, 126378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R. The analysis of perception via preference: A strategy for studying how the environment is experienced. Landsc. Plan. 1985, 12, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, R.M.; Williams, K.J.H.; Bishop, I.D.; Webb, T. A value basis for the social acceptability of clearfelling in Tasmania, Australia. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2009, 90, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zube, E.H. Perceived land use patterns and landscape values. Landsc. Ecol. 1987, 1, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischer, A.; Tsur, Y. Measuring the recreational value of agricultural landscape. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2000, 27, 385–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohua, L.; Yang, J.; Liu, P.; Chen, C.; Liu, Y. Landscape value perception and evaluation of residents on traditional villages-a case study of Zhang gu ying Village. J. Cent. China Norm. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2018, 52, 248–255. [Google Scholar]

- Rosley, M.S.F.; Lamit, H.; Rahman, S.R.A. Perceiving the Aesthetic Value of the Rural Landscape Through Valid Indicators. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 85, 318–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokocz, E.; Ryan, R.L.; Sadler, A.J. Motivations for land protection and stewardship: Exploring place attachment and rural landscape character in Massachusetts. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 99, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempesta, T. The perception of agrarian historical landscapes: A study of the Veneto plain in Italy. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 97, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.-J.; Ryu, J.-H. Sustaining a Korean Traditional Rural Landscape in the Context of Cultural Landscape. Sustainability 2015, 7, 11213–11239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wu, W.; Zhong, W. Agency and social construction of space under top-down planning: Resettled rural residents in China. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 1541–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriaza, M.; Canas Ortega, J.F.; Canas-Madueno, J.A.; Ruiz-Aviles, P. Assessing the visual quality of rural landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 69, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howley, P. Landscape aesthetics: Assessing the general publics’ preferences towards rural landscapes. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 72, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A.J.; Ryan, R.L. Place attachment and landscape preservation in rural New England: A Maine case study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 86, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.B.; Gottfredson, S.D.; Brower, S. Attachment to place: Discriminant validity, and impacts of disorder and diversity. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1985, 13, 525–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawadi, K. Place attachment as a motivation for community preservation: The demise of an old, bustling, Dubai community. Urban Stud. 2016, 54, 2973–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.L. Comparing the attitudes of local residents, planners, and developers about preserving rural character in New England. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 75, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogge, E.; Nevens, F.; Gulinck, H. Perception of rural landscapes in Flanders: Looking beyond aesthetics. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 82, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domon, G. Landscape as resource: Consequences, challenges and opportunities for rural development. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 100, 338–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, D.L.; Ryan, R.L.; De Young, R. Woodlots in the rural landscape: Landowner motivations and management attitudes in a Michigan (USA) case study. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2002, 58, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Landscape Scenes | Local Residents | Landscape Professionals | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preferences | Preservation Willingness | Preferences | Preservation Willingness | |||||

| Mean | Mean Difference 1 | Mean | Mean Difference 1 | Mean | Mean Difference 1 | Mean | Mean Difference 1 | |

| Cultural scenes | 4.02 | 4.16 | 3.43 | 3.70 | ||||

| Land boat house—Rong Shengkui | 4.15 | 0.08 | 4.57 | Reference | 3.27 | 0.58 ** | 3.65 | 0.52 ** |

| Stone road to Fu Ren high school | 4.03 | 0.20 | 4.29 | 0.29 * | 3.28 | 0.57 ** | 3.65 | 0.52 ** |

| Hui Longchang Old Avenue | 3.99 | 0.24 ** | 3.89 | 0.68 ** | 3.64 | 0.73 ** | 3.92 | 0.25 |

| New riverside Avenue | 3.89 | 0.34 | 3.89 | 0.68 ** | 3.52 | 0.33 * | 3.57 | 0.60 ** |

| Natural scenes | 3.82 | 4.05 | 3.46 | 3.74 | ||||

| Jin Xi River | 4.23 | Reference | 4.25 | 0.32 * | 3.85 | Reference | 4.17 | Reference |

| Forest with narrow road | 3.75 | 0.48 ** | 4.10 | 0.76 ** | 3.35 | 0.50 ** | 3.63 | 0.53 ** |

| Forest around mountain | 3.49 | 0.74 ** | 3.81 | 0.47 ** | 3.17 | 0.68 ** | 3.42 | 0.75 ** |

| Agricultural scenes | 3.51 | 3.69 | 3.15 | 3.60 | ||||

| Corn land | 3.53 | 0.70 ** | 3.70 | 0.87 ** | 3.15 | 0.70 ** | 3.60 | 0.57 ** |

| Vegetable land | 3.48 | 0.75 ** | 3.68 | 0.89 ** | 3.14 | 0.71 ** | 3.59 | 0.58 ** |

| Landscape | Local Residents | Landscape Professionals | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural Value | Economic Value | Recreational Value | Daily Utility Value | Cultural Value | Economic Value | Recreational Value | Daily Utility Value | |||||||||

| Mean Score | Mean Difference 1 | Mean Score | Mean Difference 1 | Mean Score | Mean Difference 1 | Mean Score | Mean Difference 1 | Mean Score | Mean Difference 1 | Mean Score | Mean Difference 1 | Mean Score | Mean Difference 1 | Mean Score | Mean Difference 1 | |

| Cultural scenes | 4.01 | 4.1 | 3.74 | 3.85 | 3.8 | 3.75 | 3.35 | 3.63 | ||||||||

| Land boat house-Rong Shengkui | 4.48 | Reference | 4.32 | Reference | 3.82 | 0.20 | 3.99 | 0.14 | 3.93 | 0.02 | 3.93 | Reference | 3.05 | 0.88** | 2.68 | 1.48 ** |

| Hui Longchang Old Avenue | 4.10 | 0.38 ** | 4.08 | 0.24 | 3.73 | 0.30* | 4.00 | 0.13 | 3.95 | Reference | 3.85 | 0.09 | 3.69 | 0.24 | 3.98 | 0.18 |

| New Riverside Avenue | 3.53 | 0.96 ** | 3.97 | 0.35 ** | 3.60 | 0.42 ** | 3.60 | 0.53 ** | 3.67 | 0.28 | 3.77 | 0.17 | 3.38 | 0.55 ** | 4.17 | Reference |

| Stone road to Fu Ren high school | 3.93 | 0.55 | 3.62 | 0.70 ** | 3.80 | 0.22 | 3.79 | 0.34 * | 3.65 | 0.30 * | 3.43 | 0.50 ** | 3.27 | 0.67 ** | 3.68 | 0.48 ** |

| Natural scenes | 3.22 | 3.62 | 3.69 | 3.85 | 2.85 | 2.89 | 3.73 | 3.09 | ||||||||

| Jin Xi River | 3.69 | 0.79 ** | 4.03 | 0.29 * | 4.02 | Reference | 4.13 | Reference | 3.57 | 0.38 * | 3.48 | 0.45 ** | 3.93 | Reference | 4.03 | 0.13 |

| Forest around mountain | 2.91 | 1.57 ** | 3.79 | 0.35 ** | 3.26 | 0.47 ** | 3.97 | 0.16 | 2.35 | 1.60 ** | 2.58 | 1.35 ** | 3.53 | 0.4 ** | 1.95 | 2.22 ** |

| Forest with narrow road | 3.07 | 1.42 ** | 3.03 | 1.29 ** | 3.78 | 0.76 ** | 3.45 | 0.68 ** | 2.62 | 1.33 ** | 2.60 | 1.33 ** | 3.73 | 0.2 | 3.28 | 0.88 ** |

| Agricultural scenes | 3.02 | 3.05 | 3.56 | 3.66 | 2.69 | 3.26 | 3.73 | 2.17 | ||||||||

| Corn land | 3.02 | 1.46 ** | 3.04 | 1.27 ** | 3.55 | 0.24 * | 3.36 | 0.77 ** | 2.70 | 1.25 ** | 3.25 | 0.68 ** | 3.72 | 0.22 | 2.15 | 2.01 ** |

| Vegetable land | 3.01 | 1.47 ** | 3.06 | 1.24 ** | 3.57 | 0.22 * | 3.36 | 0.77 ** | 2.67 | 1.28 ** | 3.24 | 0.67 ** | 3.73 | 0.2 | 2.19 | 1.98 ** |

| Landscape | Preference | Preservation Willingness | Cultural Value | Economic Value | Recreational Value | Daily Utility Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural landscape | 8.18 ** | 7.68 ** | 7.73 ** | 12.96 ** | 3.71 ** | 3.23 * |

| Natural landscape | 4.06 ** | 3.06 ** | 3.02 ** | 7.26 ** | 1.18 | 8.24 ** |

| Agricultural landscape | 2.37 * | 0.76 | 2.01 * | –1.29 | –1.17 | 9.15 ** |

| Group | Coef. | F | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural Value | Economic Value | Recreational Value | Daily Utility | ||

| Residents | 0.29 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.31 ** | 132.97 ** | |

| Professionals | 0.27 ** | 0.60 ** | 80.11 ** | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, H.; Qiu, L.; Fu, X. Toward Cultural Heritage Sustainability through Participatory Planning Based on Investigation of the Value Perceptions and Preservation Attitudes: Qing Mu Chuan, China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1171. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031171

Yang H, Qiu L, Fu X. Toward Cultural Heritage Sustainability through Participatory Planning Based on Investigation of the Value Perceptions and Preservation Attitudes: Qing Mu Chuan, China. Sustainability. 2021; 13(3):1171. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031171

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Huan, Ling Qiu, and Xin Fu. 2021. "Toward Cultural Heritage Sustainability through Participatory Planning Based on Investigation of the Value Perceptions and Preservation Attitudes: Qing Mu Chuan, China" Sustainability 13, no. 3: 1171. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031171

APA StyleYang, H., Qiu, L., & Fu, X. (2021). Toward Cultural Heritage Sustainability through Participatory Planning Based on Investigation of the Value Perceptions and Preservation Attitudes: Qing Mu Chuan, China. Sustainability, 13(3), 1171. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031171