Knowledge Network for Sustainable Local Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background of the Study

3. Method of Investigation

4. Analytical Theoretical System

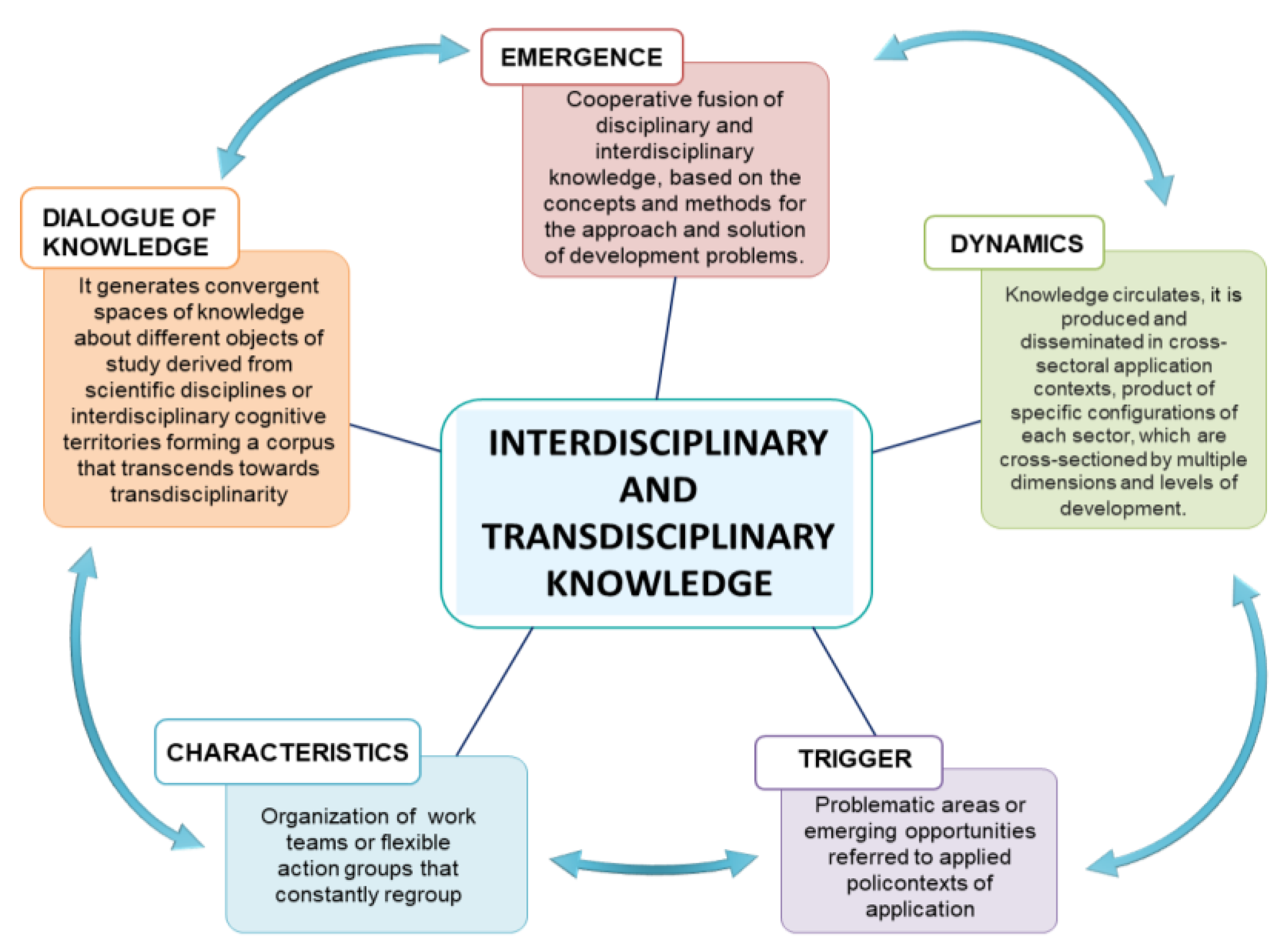

4.1. Knowledge for Local Development

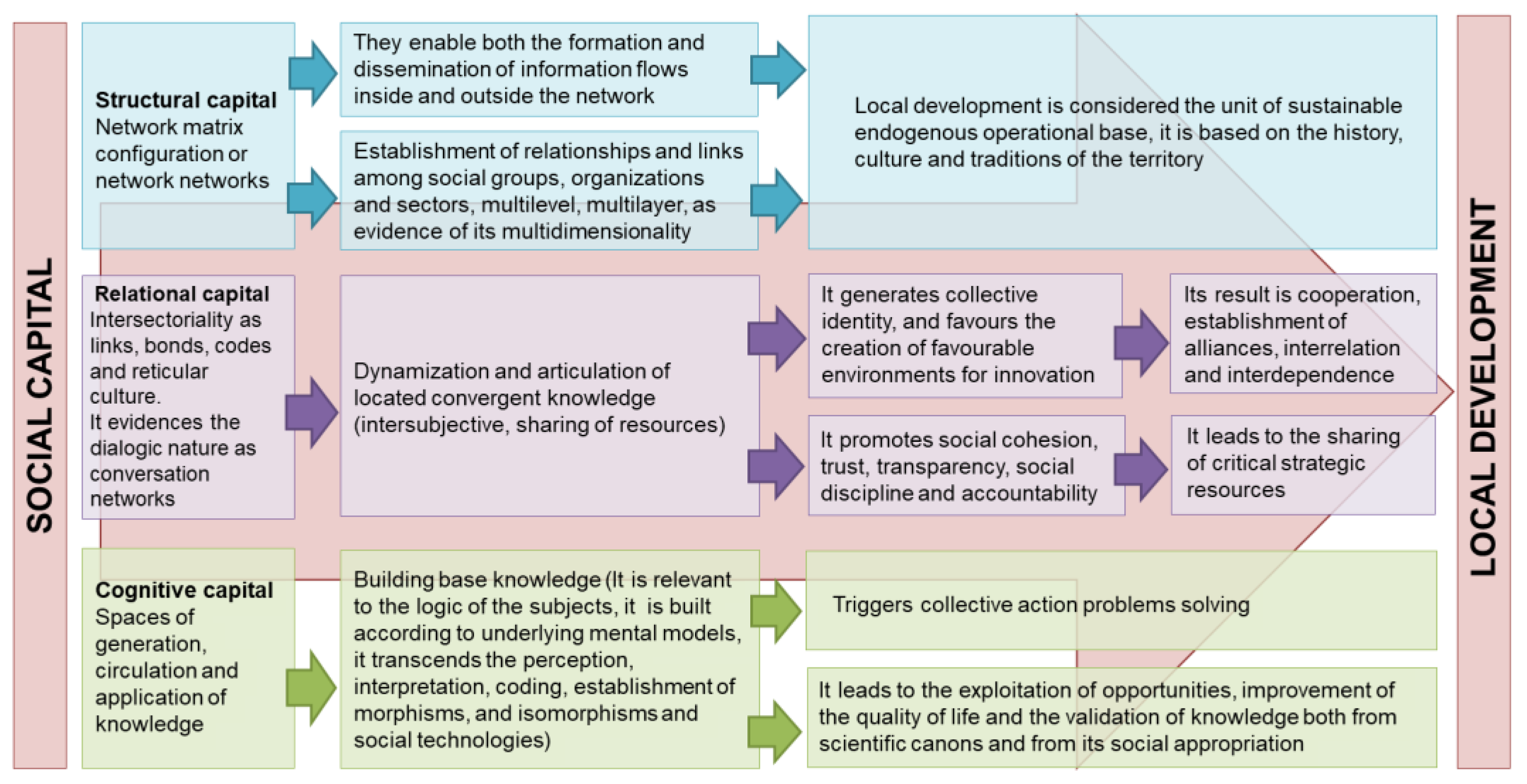

4.2. A Vision of Social Capital from the Perspective of Intersectorial Networks

5. Results and Discussion

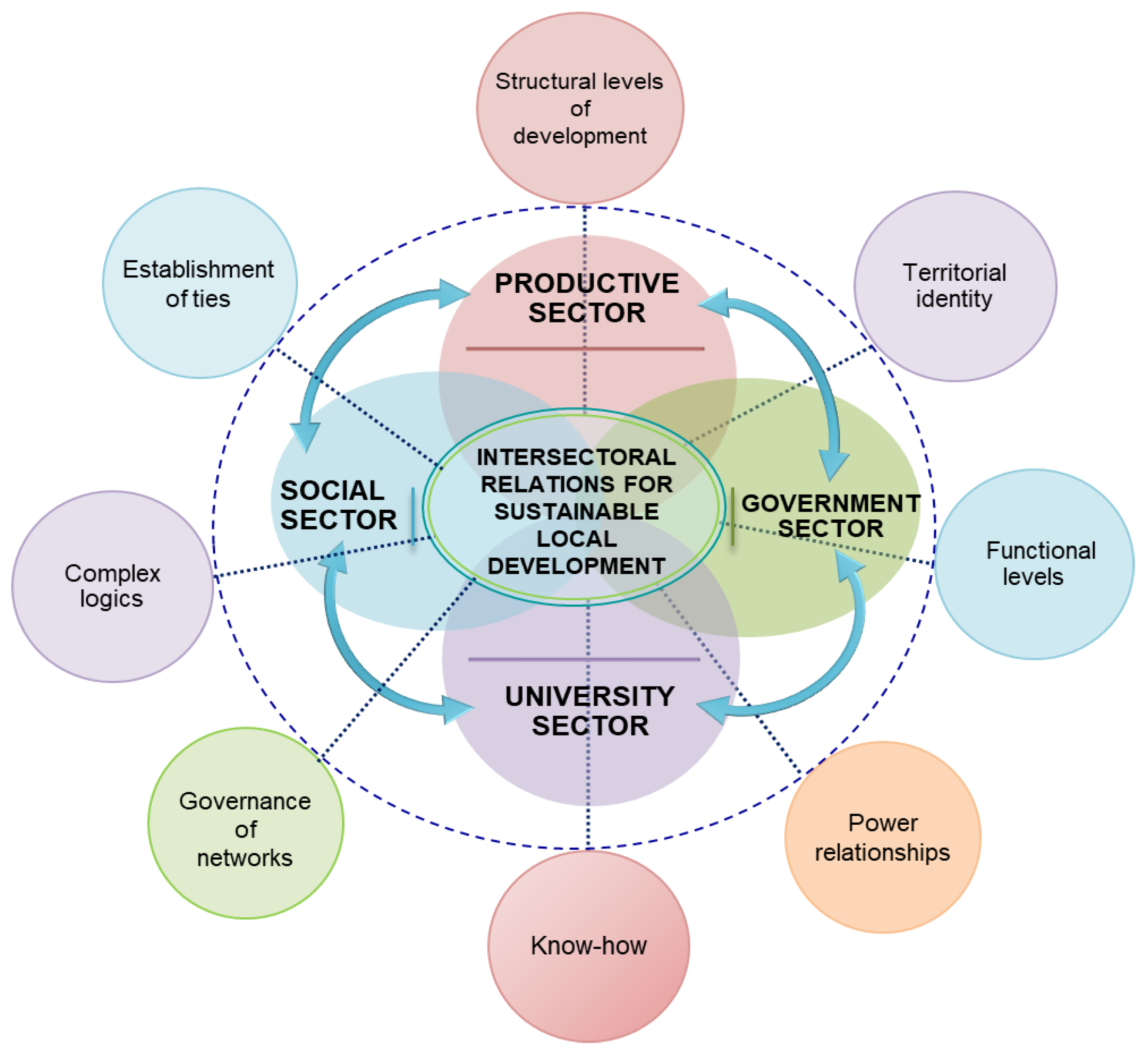

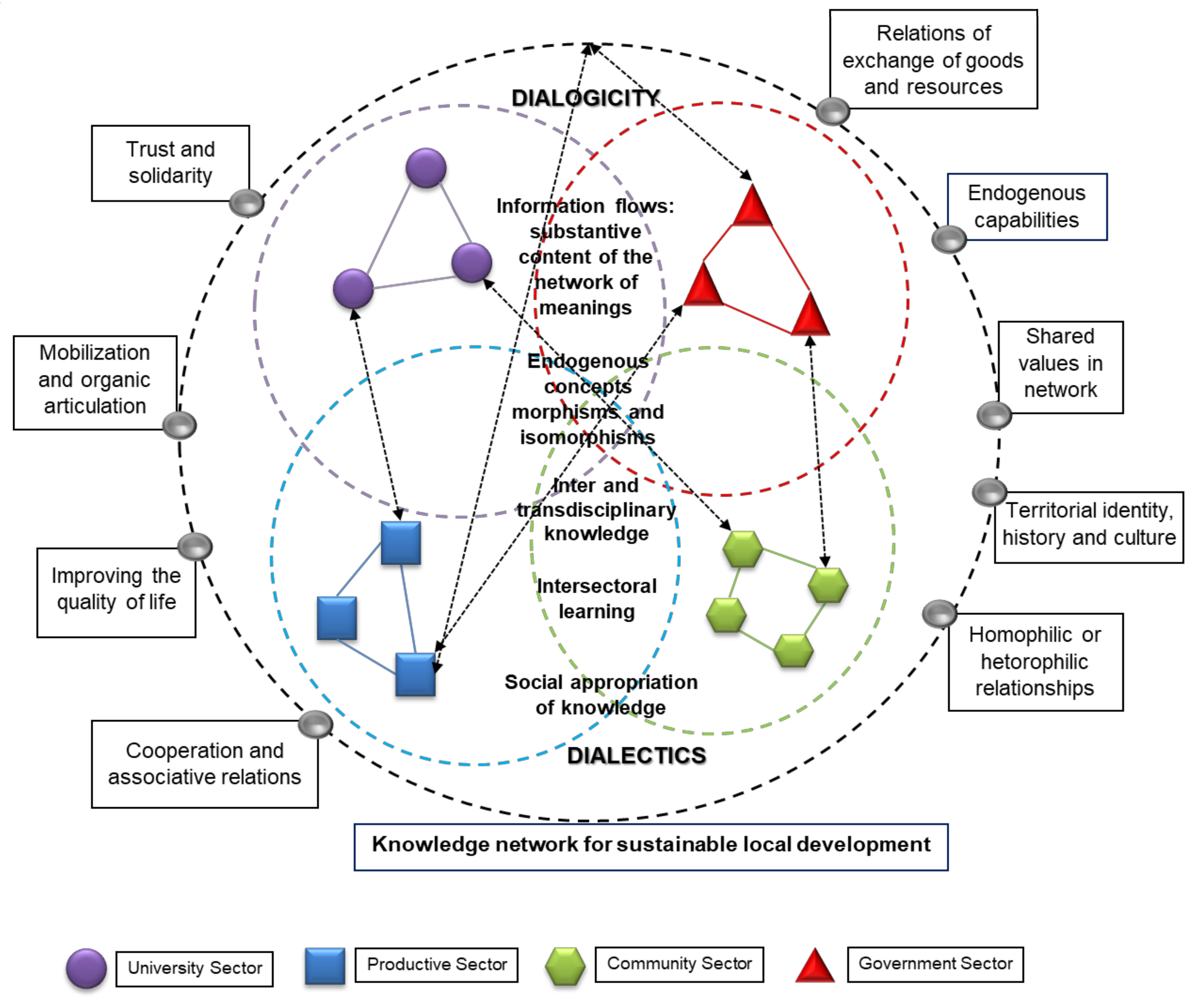

5.1. Design of a Knowledge Network for Sustainable Local Development

5.2. The Network Components

5.3. Network Operability

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tovey, H. Sustainability: A Platform for Debate. Sustainability 2009, 1, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilbanks, J.; Wilbanks, T.J. Science, Open Communication and Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2010, 2, 993–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, S.; Seferiadis, A.A.; Maas, J.; Bunders, J.F.; Zweekhorst, M.B. Knowledge, Social Capital, and Grassroots Development: Insights from Rural Bangladesh. J. Dev. Stud. 2018, 55, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesch, U.; Spekkink, W.; Quist, J. Local sustainability initiatives: Innovation and civic engagement in societal experiments. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 300–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauser, W.; Klepper, G.; Rice, M.; Schmalzbauer, B.S.; Hackmann, H.; Leemans, R.; Moore, H. Transdisciplinary global change research: The co-creation of knowledge for sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giedrė, A.; Baranauskaitė, L. Investigating Complexity of Intersectoral. Collaboration: Contextual Framework for Research. In Contemporary Research on Organization Management and Administration; Academic Association of Management and Administration: Riga, Latvia, 2018; Volume 6, Available online: http://journal.avada.lt/images/dokumentai/2018/CROMA_2018_6_1_79-89.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Berkes, F.; Seixas, C.; Fernandes, D.; Medeiros, D.; Maurice, S.; Shukla, S. Lessons from Community Self-Organization and Cross-Scale Linkages in Four Equator Initiative Projects; Natural Resources Institute, University of Manitoba: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2007; pp. 1–30. Available online: https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/bitstream/handle/10625/31457/123949.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Montalbán-Domingo, L.; Aguilar-Morocho, M.; García-Segura, T.; Pellicer, E. Study of Social and Environmental Needs for the Selection of Sustainable Criteria in the Procurement of Public Works. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerneck, A.; Olsson, L.; Ness, B.; Anderberg, S.; Baier, M.; Clark, E.; Hickler, T.; Hornborg, A.; Kronsell, A.; Lövbrand, E.; et al. Structuring sustainability science. Sustain. Sci. 2010, 6, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, R.; Maher, M.; Mann, S.; McAlpine, C.A. Integrating design thinking with sustainability science: A Researchv through Design approach. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1565–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, P.; Nepal, M.; Shyamsundar, P. Building skills for sustainability: A role for regional research networks. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cunill-Grau, N. La intersectorialidad en las nuevas políticas sociales. Un acercamiento análitico-conceptual. Gest. Polit. Pública. 2014, 23, 5–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wuelser, G.; Pohl, C. How researchers frame scientific contributions to sustainable development: A typology based on grounded theory. Sustain. Sci. 2016, 11, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weichselgartner, J.; Kasperson, R. Barriers in the science-policy-practice interface: Toward a knowledge-action-system in global environmental change research. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Erickson, T. How Cities Think: Knowledge-Action Systems Analysis for Urban Sustainability in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Ph.D. Thesis, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA, 2012. Available online: https://repository.asu.edu/attachments/94135/content//tmp/package-zUBFpT/MunozErickson_asu_0010E_11592.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Ayala-Orozco, B.; Rosell, J.A.; Merçon, J.; Bueno, I.; Alatorre-Frenk, G.; Langle-Flores, A.; Lobato, A. Challenges and Strategies in Place-Based Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration for Sustainability: Learning from Experiences in the Global South. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Deng, X.; Shi, C.; Chen, S. Exploration of the Intersectoral Relations Based on Input-Output Tables in the Inland River Basin of China. Sustainability 2015, 7, 4323–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziuzya, E.V.; Voronkova, O.Y.; Umirzakova, D.K.; Rakovskiy, V.I.; Qurbanov, P.A.; Kazakov, A.V. A Methodological Approach to Assessing the Efficiency of the Economic Mechanism for Formation and Development of Intersectoral Linkages. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 10, 920–925. [Google Scholar]

- Scheunemann-De Souza, I.S. Política y Gestión de las Redes. In Redes de Conocimiento Construcción, Dinámica y Gestión, 1st ed.; Albornoz, M., Alfaraz, C., Eds.; Red Iberoamericana de Indicadores de Ciencia y Tecnología (RICYT) del Programa Iberoamericano de Ciencia y Tecnología para el Desarrollo (CYTED) y la Oficina Regional de Ciencia para América Latina y el Caribe de la UNESCO: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2006; pp. 215–218. Available online: http://repositorio.minciencias.gov.co:8080/bitstream/handle/11146/468/1669-ALBORNOZ_2006_REDES_DE_CONO.PDF?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Kaiser, D.B.; Weith, T.; Gaasch, N. Co-Production of Knowledge: A Conceptual Approach for Integrative Knowledge Management in Planning. Trans. Assoc. Eur. Sch. Plan. 2017, 1, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, C.; Rist, S.; Zimmermann, A.; Fry, P.; Gurung, G.S.; Schneider, F.; Speranza, C.I.; Kiteme, B.; Boillat, S.; Serrano, E.; et al. Researchers’ roles in knowledge co-production: Experience from sustainability research in Kenya, Switzerland, Bolivia and Nepal. Sci. Public Policy 2010, 37, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNie, E.C. Reconciling the supply of scientific information with user demands: An analysis of the problem and review of the literature. Environ. Sci. Policy 2007, 10, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Real, J.L.; Uribe-Toril, J.; Valenciano, J.D.P.; Manso, J.P. Ibero-American Research on Local Development. An Analysis of Its Evolution and New Trends. Resources 2019, 8, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, E. Social-Ecological Systems as Epistemic Objects. In Human-Nature Interactions in the Anthropocene: Potentials of Social Ecological Systems Analysis; Marion, G.G.K., Beate, R.M., Eds.; Welp Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 37–59. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256259334_Social-Ecological_Systems_as_Epistemic_Objects (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Díaz, A.L.; Chan, A.; Harley, K.; Matus, S.; Suerie Moon, W.C.; Murthy, C.W. Making Technological Innovation Work for Sustainable Development. Harvard Kennedy School University Faculty Research Working Paper Series; London, UK, 2015; pp. 15–79. Available online: https://research.hks.harvard.edu/publications/getFile.aspx?Id=1294 (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Lang, D.; Wiek, A.; Bergmann, M.; Stauffacher, M.; Martens, P.; Moll, P.; Swilling, M.; Thomas, C.J. Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: Practice, principles, and challenges. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safak, B. The Relation between Social Capital and Trust with Social Network Analysis World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology. IJCTE 2016, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, L.; LaHurd, A.; Wasson, E.; McClarin, L.; Dabney, K.W. Racial and Ethnic Heterogeneity in the Association Between Total Cholesterol and Pediatric Obesity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, L.; Dale, A. Homophily and Agency: Creating Effective Sustainable Development Networks. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2007, 9, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, H. Realism without absolutes. Int. J. Philos. Stud. 1993, 1, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu-Bing, W.; Ching-Wei, H. No Money? No Problem! The Value of Sustainability: Social Capital Drives the Relationship among Customer Identification and Citizenship Behavior in Sharing Economy. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhola, S.; Westerhoff, L. Challenges of adaptation to climate change across multiple scales: A case study of network governance in two European countries. Environ. Sci. Policy 2011, 14, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Yang, S. Neighborhood Walking and Social Capital: The Correlation between Walking Experience and Individual Perception of Social Capital. Sustainability 2017, 9, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdol Aziz, S. Sustainable regional development through knowledge networks: Review of case studies. Front. Archit. Res. 2019, 8, 471–482. [Google Scholar]

- Staat, W. On abduction, deduction, induction and categories. Trans. Charles S Peirce Soc. 1993, 29, 225–237. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, A. Basic debates and methodological practices. Methods of Discovery: Heuristics for the Social Sciences. Chapter 2. 2004, pp. 19–39. Available online: https://www.humanscience.org/docs/Abbott%20(2004)%20Methods%20of%20Discovery%202.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Mirza, N. Effects of abductive reasoning training on hypothesis generation abilities of first and second year baccalaureate nursing students. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy, McMaster University. Copyright by Noeman Ahmad Mirza. 2015. Available online: https://macsphere.mcmaster.ca/bitstream/11375/18113/2/Noeman%20Mirza%20FINAL%20Thesis%20D29M06Y2015.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Burawoy, M. The Extended Case Method Four Countries, Four Decades, Four Great Transformations, and One Theoretical Tradition. 2008, pp. 192–219. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285934790_The_extended_case_method_Four_countries_four_decades_four_great_transformations_and_one_theoretical_tradition (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Quaranta, G.; Citro, E.; Salvia, R. Economic and Social Sustainable Synergies to Promote Innovations in Rural Tourism and Local Development. Sustainability 2016, 8, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, J. Sustainable development: Meaning, history, principles, pillars, and implications for human action: Literature review. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2019, 5, 1653531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonescu, D. Theoretical Approaches of Endogenous Regional Development; Institute of National Economy: Bucharest, Romania, 2015; MPRA is a RePEc Service Hosted by the Munich University Library in Germany; Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/64679/ (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Meisert, A.; Böttcher, F. Towards a Discourse-Based Understanding of Sustainability Education and Decision Making. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorén, H. The Hammer and the Nail: Interdisciplinary and Problem Solving in Sustainability Science. Ph.D. Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2015. Available online: https://portal.research.lu.se/ws/files/6044493/5048299.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Walker, B.H.; Carpenter, S.R.; Anderies, J.M.; Abel, N.; Cumming, G.S.; Janssen, M.A.; Lebel, L.; Norberg, J.; Peterson, G.; Pritchard, R. Resilience Management in Social-ecological Systems: A Working Hypothesis for a Participatory Approach. Conserv. Ecol. 2002, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, L.; Binder, C. Participation as Relational Space: A Critical Approach to Analysing Participation in Sustainability Research. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziervogel, G.; Archer, E.; Price, P. Strengthening the knowledge–policy interface through co-production of a climate adaptation plan: Leveraging opportunities in Bergrivier Municipality, South Africa. Environ. Urban. 2016, 28, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorén, H.; Persson, J. The Philosophy of Interdisciplinarity: Sustainability Science and Problem-Feeding. J. Gen. Philos. Sci. 2013, 44, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righi, A. Measuring Social Capital: Official Statistics Initiatives in Italy. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 72, 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social Capital, Intellectual Capital and the Organizational Advantage. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco-Bocigas, P.; Navas-López, E.; López-Sáez, P. El efecto mediador del capital social sobre los beneficios de la empresa: Una aproximación teórica. Cuad. Estud. Empresariales 2010, 20, 11–34. [Google Scholar]

- Brink, E.; Wamsler, C.; Adolfsson, M.; Axelsson, M.; Beery, T.; Björn, H.; Bramryd, T.; Ekelund, N.; Jephson, T.; Narvelo, W.; et al. On the road to ‘research municipalities’: Analysing transdisciplinarity in municipal ecosystem services and adaptation planning. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 765–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, B.; Donate, M.J.; Guadamillas, F. Relational and Cognitive Social Capital: Their Influence on Strategies of External Knowledge Acquisition. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 99, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Foster, P.C. The Network Paradigm in Organizational Research: A Review and Typology. J. Manag. 2003, 29, 991–1013. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Diez, S.G. Measurement of Social Capital with the Help of Time Use Surveys. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 72, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carrillo-Álvarez, E.; Riera-Roman, J. Measuring social capital: Further insights. Gaceta Sanitari 2017, 31, 57–61. Available online: http://scielo.isciii.es/pdf/gs/v31n1/0213-9111-gs-31-01-00057.pdf (accessed on 4 November 2020).

- Chen, C.J.; Huang, J. How organizational climate and structure affect knowledge management—The social interaction perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2007, 27, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, T.; Su, Y.; Wang, Y. Examining Relationships between Social Capital, Emotion Experience and Life Satisfaction for Sustainable Community. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, M.; Nalau, J.; Fisher, K. Perspectivas alternativas sobre la sostenibilidad: Conocimiento y metodologías indígenas. Chall. Sustain. 2017, 5, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessels, L.K.; Van Lente, H. Re-thinking new knowledge production: A literature review and a research agenda. Res. Policy 2008, 37, 740–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichselgartner, J.; Kelman, I. Geographies of resilience. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2015, 39, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.C.; Cvitanovic, C. An introduction to achieving policy impact for early career researchers. Palgrave Commun. 2018, 4, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, D.R.; De Loë, R.; Plummer, R. Environmental governance and its implications for conservation practice. Conserv. Lett. 2012, 5, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opdam, P.; Luque, S.; Nassauer, J.; Verburg, P.; Wu, J. How can landscape ecology contribute to sustainability science? Landsc. Ecol. 2018, 33, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marín-González, F.; Senior-Naveda, A.; Castro, M.N.; González, A.I.; Chacín, A.J.P. Knowledge Network for Sustainable Local Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031124

Marín-González F, Senior-Naveda A, Castro MN, González AI, Chacín AJP. Knowledge Network for Sustainable Local Development. Sustainability. 2021; 13(3):1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031124

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarín-González, Freddy, Alexa Senior-Naveda, Mercy Narváez Castro, Alicia Inciarte González, and Ana Judith Paredes Chacín. 2021. "Knowledge Network for Sustainable Local Development" Sustainability 13, no. 3: 1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031124

APA StyleMarín-González, F., Senior-Naveda, A., Castro, M. N., González, A. I., & Chacín, A. J. P. (2021). Knowledge Network for Sustainable Local Development. Sustainability, 13(3), 1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031124