Does Customer Orientation Matter? Direct and Indirect Effects in a Service Quality-Sustainable Restaurant Satisfaction Framework in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

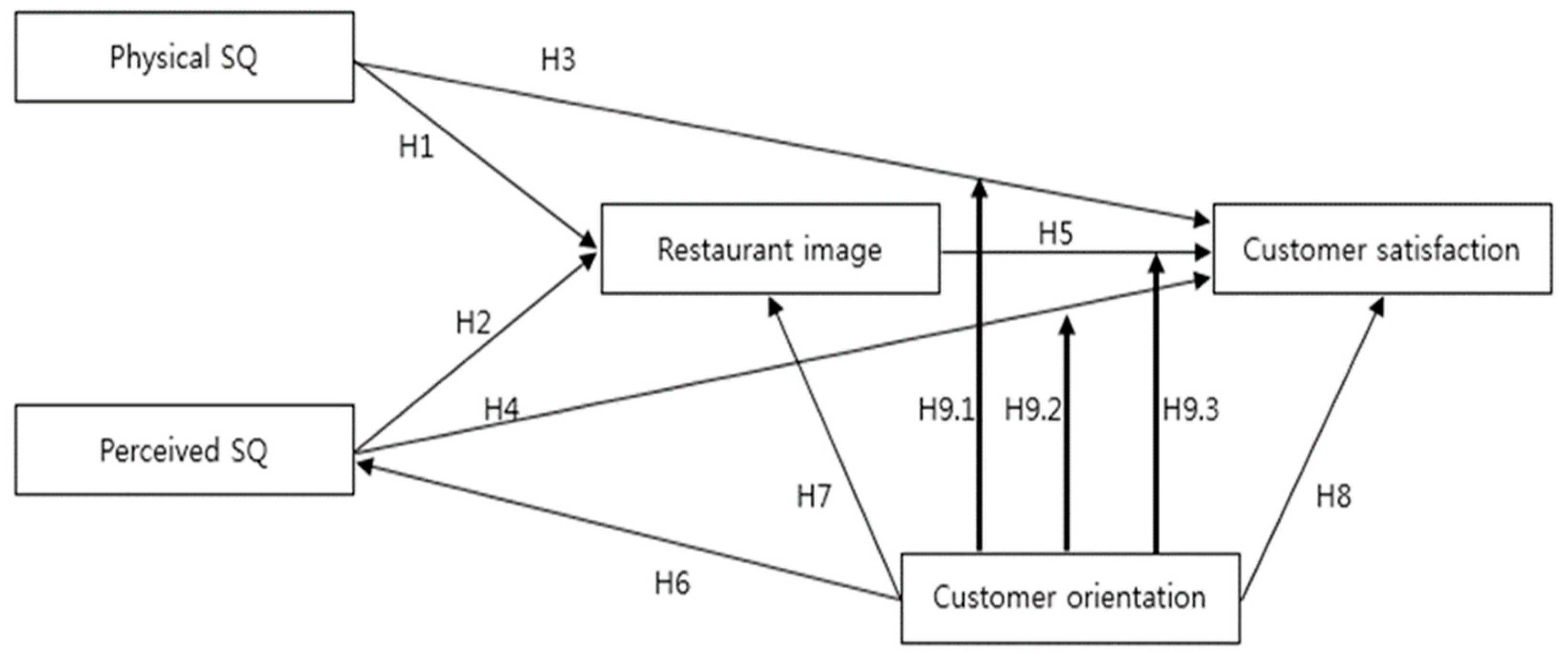

2.1. Service Quality and Restaurant Image

2.2. Service Quality, Restaurant Image and Customer Satisfaction

2.3. Customer Orientation

2.4. Moderating Role of Customer Orientation

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Direct Effects between Quality Evaluations, Restaurant Image and Customer Satisfaction

4.2. Direct Effects of Customer Orientation

4.3. Moderating Effects of Customer Orientation

5. Discussion

Limitations and Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bell, S.J.; Auh, S.; Smalley, K. Customer relationship dynamics: Service quality and customer loyalty in the context of varying levels of customer expertise and switching costs. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2005, 33, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladhari, R. Alternative measures of service quality: A review. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2008, 18, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, N.K.; Simmers, C.S. Measuring service quality perceptions of restaurant experiences: The disparity between comment cards and DINESERV. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2011, 14, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutson, B.; Stevens, P.; Patton, M. DINESERV: Measuring service quality in quick service, casual/theme, and fine dining restaurants. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 1996, 3, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreng, R.A.; Mackoy, R.D. An empirical examination of a model of perceived service quality and satisfaction. J. Retail. 1996, 72, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.A.; Baker, T.L. An assessment of the relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction in the formation of consumers’ purchase intentions. J. Retail. 1994, 70, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J.; Brady, M.K.; Hult, G.T.M. Assessing the effects of quality, value, and satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Han, H. Influence of the quality of food, service, and physical environment on customer satisfaction and behavioral intention in quick-casual restaurants: Moderating role of perceived price. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2010, 34, 310–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M.K.; Robertson, C.J. Searching for a consensus on the antecedent role of service quality and satisfaction: An exploratory cross-national study. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 51, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J. Service orientation, service quality, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty: Testing a structural model. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2011, 20, 619–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisingerich, A.B.; Bell, S.J. Does enhancing customers’ service knowledge matter? J. Serv. Res. 2008, 10, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M.K.; Cronin, J.J. Some new thoughts on conceptualizing perceived service quality: A hierarchical approach. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabholkar, P.A.; Thorpe, D.I.; Rentz, J.O. A measure of service quality for retail stores: Scale development and validation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1996, 24, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M.E.A.; Comesań, L.R.; Brea, J.A.F. Assessing tourist behavioral intentions through perceived service quality and customer satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, K.; Jing, F.; Parveen, K. How do foreigners perceive? Exploring foreign diners’ satisfaction with service quality of Chinese restaurants. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhagar, D.P.; Rajendran, G. Selection criteria of customers of Chinese restaurants and their dining habits. Int. J. Knowl. Manag. Tour. Hosp. 2017, 1, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M.J. Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M.K.; Cronin, J.J. Customer orientation: Effects on customer service perceptions and outcome behaviors. J. Serv. Res. 2001, 3, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinkula, J.M.; Baker, W.E.; Noordewier, T. A framework for market-based organizational learning: Linking values, knowledge and behavior. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1997, 25, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU-SME Center. The Food & Beverage Market in China; China-Britain Business Council: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Full-Service Restaurants in China. Beijing, China. January 2015. Available online: http://store.mintel.com/full-service-restaurants-china-january-2015?cookie_test=true (accessed on 18 January 2019).

- Chow, I.H.; Lau, V.P.; Lo, T.W.; Sha, Z.; Yun, H. Service quality in restaurant operations in China: Decision- and experiential-oriented perspectives. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2007, 26, 698–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins-Dodd, C.; Lindley, T. Store brands and retail differentiation: The influence of store image and store brand attitude on store own brand perceptions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2003, 10, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.; Pearo, L.K.; Widener, S.K. Linking customer satisfaction to the service concept and customer characteristics. J. Serv. Res. 2008, 10, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J.; Taylor, S.A. Measuring service quality: A reexamination and extension. J. Mark. 1992, 56, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.; Donthu, N.; Lee, S. An examination of selected marketing mix elements and brand equity. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.C.; Weber, A.J.; Meiselman, H.L.; Lv, N. The effect of meal situation, social interaction, physical environment and choice on food acceptability. Food Qual. Prefer. 2004, 15, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L. SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, K.; Han, H.; Kim, T. The relationships among overall quick-casual restaurant image, perceived value, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2008, 27, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivela, J.; Inbakaran, R.; Reece, J. Consumer research in the restaurant environment, Part 1: A conceptual model of dining satisfaction and return patronage. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 1999, 11, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Lee, H.; Kim, W. The influence of the quality of the physical environment, food, and service on restaurant image, customer perceived image, customer perceived value, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 24, 200–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Erramilli, K.M.; Dev, C.D. Market orientation and performance in service firms: Role of innovation. J. Serv. Mark. 2003, 17, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandvik, I.L.; Sandvik, K. The impact of market orientation on product innovativeness and business performance. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2003, 20, 355–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirca, A.H.; Jayachandran, S.; Bearden, W.O. Market orientation: A meta-analytic review and assessment of its antecedents and impact on performance. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloemer, J.; Ruyter, K. On the relationship between store image, store satisfaction and store loyalty. Eur. J. Mark. 1998, 32, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, C.B.; Armario, M.; Ruiz, M. The influence of market heterogeneity on the relationship between a destination’s image and tourists’ future behavior. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, K.B.; Spiro, R. Recapturing store image in customer-based store equity: A construct conceptualization. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 1112–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; Brinberg, D. Affective images of tourism destinations. J. Travel Res. 1997, 35, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Zhao, J.; Joung, H. Influence of price and brand image on restaurant customers’ restaurant selection attribute. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2018, 21, 200–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, E.A.; Berry, L.L. The combined effects of the physical environment and employee behavior on customer perception of restaurant service quality. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2007, 48, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysenko-Ryba, K.; Zimon, D. Customer behavioral reactions to negative experiences during the product return. Sustainability 2021, 13, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, B.L.; Bush, R.F.; Hair, J.F. The self-image/ store image matching process: An empirical test. J. Bus. 1977, 50, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cretu, A.E.; Brodie, R.J. The influence of brand image and company reputation where manufacturers market to small firms: A customer value perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, L.; Kanuk, L.L. Consumer Behavior; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer, 2nd ed.; M.E. Sharpe: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ragunathan, R.; Irwin, J.R. Walking the hedonic product treadmill: Default contrast and mood-based assimilation in judgments of predicted happiness with a target product. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 28, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.E.; Srinivasan, S.S. E-satisfaction and e-loyalty: A contingency framework. Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, A.; Peng, C.; Huang, H.; Yeh, S. Effects of corporate social responsibility on firm performance: Does customer satisfaction matter? Sustainability 2020, 12, 7545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Jang, S. Influence of restaurants’ physical environments on emotion and behavioral intention. Serv. Ind. J. 2008, 28, 1151–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.C.; Ezeh, C. Servicescape and loyalty intentions: An empirical investigation. Eur. J. Mark. 2008, 42, 390–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.G.; Moon, Y.J. Customers’ cognitive, emotional, and actionable response to the servicescape: A test of the moderating effect of the restaurant type. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajewska, T.; Zimon, D.; Kaczor, G.; Madzík, P. The impact of the level of customer satisfaction on the quality of e-commerce services. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2019, 69, 666–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bove, L.L.; Johnson, L.W. A customer-service worker relationship model. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2000, 11, 491–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.; John, J. Role of customer orientation in an integrative model of brand loyalty in services. Serv. Ind. J. 2010, 30, 1025–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxe, R.; Weitz, B.A. The SOSO scale: A measure of the customer orientation of salespeople. J. Mark. Res. 1982, 19, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.; Chen, S. Market orientation, service quality and business profitability: A conceptual model and empirical evidence. J. Serv. Mark. 1998, 12, 246–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Križo, P.; Madzík, P.; Vilgová, Z.; Sirotiaková, M. Evaluation of the most frequented forms of customer feedback acquisition and analysis. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Management in Organizations, Zilina, Slovakia, 6–10 August 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 562–573. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. The four service marketing myths: Remnants of a goods-based, manufacturing model. J. Serv. Res. 2004, 6, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.J.; Kim, T.T.; Lee, G. When customer complain: The value of customer orientation in service recovery. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2015, 56, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, S.W. Developing customer orientation among service employees. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1992, 20, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, S.W.; Hoffman, K.D. An investigation of positive affect, prosocial behaviors and service quality. J. Retail. 1997, 73, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.J.; Mowen, J.C.; Donavan, T.; Licata, J.W. The customer orientation of service workers: Personality trait effects on self- and supervisor performance ratings. J. Mark. Res. 2002, 39, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, N.A.; Vorhies, D.W.; Mason, C.H. Market orientation, marketing capabilities, and firm performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmington, N.; King, C. Key dimensions of outsourcing hotel food and beverage services. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2000, 12, 256–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, N.; Pine, R. Consumer behavior in the food service industry: A review. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2002, 21, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, S.J.; Overton, T.S. Estimating non-response in mailed surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B. Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Understanding Concepts and Application; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equations models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Yap, S.F.; Makkar, M. Home sharing in marketing and tourism at a tipping point: What do we know, how do we know, and where should we be heading? J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 534–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, W.M. The sharing economy: A marketing perspective. Australas. Mark. J. 2020, 28, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LIM, W.M.; Phang, C.S.C.; Lim, A.L. The effects of possession-and social inclusion-defined materialism on consumer behavior toward economical versus luxury product categories, goods versus services product types, and individual versus group marketplace scenarios. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 56, 102158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Factor Loading | t-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Customer Orientation | ||

| Employees go beyond normal call of duty to please customers. | 0.76 | 15.39 |

| Employees understand what service attributes customer value most. | 0.68 | 14.06 |

| Employees are given adequate resources to meet customer needs. | 0.54 | 11.41 |

| Employees understand customers’ real problems. | 0.72 | 14.74 |

| Composite reliability | 0.86 | |

| Average variance extracted | 0.47 | |

| Restaurant Image | ||

| I have a favorable attitude to the restaurant. | 0.69 | 14.26 |

| I trust the restaurant’s image. | 0.73 | 15.07 |

| The restaurant has an overall goodwill with me. | 0.75 | 15.35 |

| The restaurant carries a wide selection of different kinds of services. | 0.75 | 15.34 |

| Composite reliability | 0.88 | |

| Average variance extracted | 0.54 | |

| Physical Service Quality | ||

| The physical facilities of the restaurant are visually appealing. | 0.72 | 14.33 |

| The restaurant has a pleasant eating environment. | 0.68 | 13.66 |

| The interior furnishing in the restaurant gives the customer the appearance and feeling of a quality restaurant. | 0.69 | 13.84 |

| The layout at this restaurant makes it easy for customers to find what they need. | 0.72 | 14.34 |

| Composite reliability | 0.86 | |

| Average variance extracted | 0.50 | |

| Perceived Service Quality | ||

| The restaurant is of high quality. | 0.72 | 14.38 |

| The likelihood that the restaurant is reliable is very high. | 0.69 | 13.71 |

| The likely quality of the restaurant is extremely high. | 0.67 | 14.05 |

| Composite reliability | 0.85 | |

| Average variance extracted | 0.49 | |

| Satisfaction | ||

| Overall, I am satisfied with specific experiences with the restaurant. | 0.74 | 15.89 |

| I am satisfied with my decision to experience from this restaurant. | 0.78 | 16.73 |

| Composite reliability | 0.88 | |

| Average variance extracted | 0.58 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Customer orientation | 0.47 | 3.42 | 1.01 | ||||

| 2. Restaurant image | 0.39 | 0.54 | 3.61 | 1.01 | |||

| 3. Physical service quality | 0.45 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 3.62 | 1.03 | ||

| 4. Perceived service quality | 0.39 | 0.42 | 0.51 | 0.49 | 3.63 | 0.95 | |

| 5. Satisfaction | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.59 | 0.51 | 0.58 | 3.54 | 0.89 |

| Direct Paths | Coefficient | Support |

|---|---|---|

| H1: Physical SQ → Restaurant image | 0.355 ** | Yes |

| H2: Perceived SQ → Restaurant image | 0.483 ** | Yes |

| H3: Physical SQ → Customer satisfaction | 0.188 ** | Yes |

| H4: Perceived SQ → Customer satisfaction | 0.465 ** | Yes |

| H5: Restaurant image → Customer satisfaction | 0.012 | No |

| H6: Customer orientation → Perceived SQ | 0.800 ** | Yes |

| H7: Customer orientation → Restaurant image | 0.318 ** | Yes |

| H8: Customer orientation → Customer satisfaction | 0.391 ** | Yes |

| Hypotheses | Beta | SEb | t-Value | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H9.1 | Std. Beta | SE | t | P | LLCI | ULCI |

| Constant | 1.87 | 0.27 | 6.71 | 0.000 | 1.328 | 2.427 |

| Customer orientation (CO) | −0.31 | 0.19 | −1.65 | 0.097 | −0.695 | 0.0587 |

| Physical service quality (PSQ) | −0.01 | 0.08 | −0.10 | 0.917 | −0.167 | 0.150 |

| PSQ * CO | 0.17 | 0.05 | 3.37 | 0.001 | 0.072 | 0.274 |

| Conditional effect of PSQ on customer satisfaction at values of the moderator | ||||||

| Std. Beta | SE | t | P | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Low CO | 0.16 | 0.03 | 4.60 | 0.000 | 0.094 | 0.235 |

| High CO | 0.34 | 0.03 | 9.17 | 0.000 | 0.266 | 0.411 |

| Model: R2 = 0.37; F = 107.811 (df1 = 3.0, df2 = 542, p = 0.000) | ||||||

| H9.2 | Std. Beta | SE | t | P | LLCI | ULCI |

| Constant | 1.38 | 0.28 | 4.88 | 0.000 | 0.826 | 1.939 |

| Customer orientation (CO) | −0.16 | 0.19 | −0.82 | 0.410 | −0.542 | 0.221 |

| Perceived service quality (PESQ) | 0.15 | 0.08 | 1.85 | 0.064 | −0.008 | 0.311 |

| PESQ * CO | 0.12 | 0.05 | 2.24 | 0.025 | 0.014 | 0.220 |

| Conditional effect of PESQ on customer satisfaction at values of the moderator | ||||||

| Std. Beta | SE | t | P | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Low CO | 0.26 | 0.03 | 7.44 | 0.000 | 0.197 | 0.339 |

| High CO | 0.38 | 0.03 | 10.21 | 0.000 | 0.311 | 0.460 |

| Model: R2 = 0.42; F = 132.708 (df1 = 3.0, df2 = 543, p = 0.000) | ||||||

| H9.3 | Std. Beta | SE | t | P | LLCI | ULCI |

| Constant | 1.33 | 0.28 | 4.72 | 0.000 | 0.777 | 1.883 |

| Customer orientation (CO) | −0.03 | 0.19 | −0.15 | 0.877 | −0.405 | 0.346 |

| Restaurant image (RI) | 0.17 | 0.08 | 2.06 | 0.039 | 0.008 | 0.332 |

| RI * CO | 0.08 | 0.05 | 1.54 | 0.123 | −0.021 | 0.182 |

| Conditional effect of RI on customer satisfaction at values of the moderator | ||||||

| Std. Beta | SE | t | P | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Low CO | 0.25 | 0.03 | 6.76 | 0.000 | 0.177 | 0.323 |

| High CO | 0.33 | 0.03 | 9.08 | 0.000 | 0.259 | 0.402 |

| Model: R2 = 0.39; F = 118.629 (df1 = 3.0, df2 = 543, p = 0.000) | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xia, Y.; Ha, H.-Y. Does Customer Orientation Matter? Direct and Indirect Effects in a Service Quality-Sustainable Restaurant Satisfaction Framework in China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031051

Xia Y, Ha H-Y. Does Customer Orientation Matter? Direct and Indirect Effects in a Service Quality-Sustainable Restaurant Satisfaction Framework in China. Sustainability. 2021; 13(3):1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031051

Chicago/Turabian StyleXia, Yingxue, and Hong-Youl Ha. 2021. "Does Customer Orientation Matter? Direct and Indirect Effects in a Service Quality-Sustainable Restaurant Satisfaction Framework in China" Sustainability 13, no. 3: 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031051

APA StyleXia, Y., & Ha, H.-Y. (2021). Does Customer Orientation Matter? Direct and Indirect Effects in a Service Quality-Sustainable Restaurant Satisfaction Framework in China. Sustainability, 13(3), 1051. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13031051