Abstract

A lockdown is a set of restrictive actions, in the implementation of which countries face a case of chain reaction: In order to protect human lives and health, the states, due to imbalances in fiscal and monetary policies caused by uncollected planned revenues and unplanned excessive budget expenditures, experience a socio-economic recession. The current paper focuses on the first lockdown implemented in Lithuania to control the spread of COVID-19, which took place from 16 March, 2020 until 16 June, 2020. The main object of the paper is the components that defined the efficiency of the government intervention measures intended to support businesses affected by the first lockdown regime. By generating the mentioned components, we followed the principle of the philosophy of sustainable development: the interdependence of economic, social, environmental, and institutional elements; coherence; and sustainable development. Efficiency is the art of choice, where it is necessary to anticipate the final aim, resulting in maximum benefit from the arrangement of the available limited resources. However, in order to measure the effectiveness of government interventions, we were faced with differences in interpretations of the measurement of the effectiveness of policy decisions. In the course of the research, after analysing secondary data, we identified and, by means of modelling techniques, visualised the main components to estimate the efficiency of the government intervention measures. The theoretical model demonstrated that economic instruments—volume, price, time, transparency, and results—defined the efficiency of their implementation.

1. Introduction

When in December 2019 an outbreak of a new virus, little known to medical science, which later became known as SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19, was reported in Wuhan, China, probably no country in the world or their business, research, or governmental institutions were preparing for a world-class pandemic, which was subsequently announced by the World Health Organization on 11 March [1]. Due to the rapid spread of infection and the sudden increase in the number of infections, countries successively introduced lockdown regimes that differed in both their content and the duration of the restrictions. That caused problems for industries closely integrated into international production and supply chains, as well as for citizens living or working abroad.

Most countries applied rather strict lockdown regimes and related restrictions on the activities of natural persons and legal entities. Strict lockdown regimes were applied in the countries particularly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: Spain, Italy, and France. Medium-strict lockdown mechanisms were applied in Austria, Estonia, and Latvia. There were also cases of a combined lockdown regime, where the overall national lockdown regime was mild, however, individual areas were subject to strict conditions: the German state of Bavaria, the Austrian federal state of Tyrol, and the Estonian islands of Saaremaa and Muhu [2]. Sweden was the only country to introduce very lenient measures of a purely recommendatory nature to control the spread of the virus.

The lockdown regime was one of the means to prevent the spread of the virus [3], however, the spring lockdown, introduced both in Lithuania and in the world with the aim of preventing the spread of COVID-19, little known to medicine, was not the first time in human history. The first cases of a lockdown regime were detected as early as the 5th century B.C., when Hippocrates described a number of communicable diseases that involved the isolation of a sick or potentially sick person from healthy members of the community for 40 days (a quarantine), and the 40th day after the viral infection was considered a critical point after which the person was harmless to the community. The principle was followed by all Ancient Greek medicine [4]. The concept of a structural lockdown, very much in line with our times, is believed to have originated in Western Europe at the earliest in the 14th century in the fight against the plague epidemic: It was characterised by trade-restrictive procedures, and the first economic stimulus measures could be discerned [5]. The very concept of a lockdown, or “a quarantine,” was defined only in 1663 and included in the Oxford English Dictionary: It meant a period of 40 days during which all persons with a contagious disease had to observe and to avoid contact with non-infected members of the community. In addition, the quarantine had to be observed by all persons wishing to enter the country [5]. Researchers on epidemics [4,6,7] came to the conclusion that efficient management of the spread of any disease required a coherent and equally understood communication between the health system, government, and society.

The main aim of the lockdown regime was to prevent the spread of the first wave of COVID-19, which varied from country to country in terms of the start and end of the lockdown initiation but tentatively occurred during the first six months of 2020, was to partially or completely limit people’s contacts, which was done by forcibly closing high-traffic-generating points (shopping and leisure centres, cultural and educational institutions and events, etc.) or by recommending to not get together. In principle, due to operation restrictions applied during the lockdown, business entities could be divided into three groups: (i) fully operational, (ii) partially operational, and (iii) fully suspended business entities. Providers of restaurants and hotels, entertainment and leisure, and aesthetics and beauty services suffered the most from the first lockdown regime. It is only natural that due to restricted operation and a sudden decrease in demand for services and goods provided, businesses, in accordance with the provisions of the National Labour Code, (i) sent some or all of their staff to full or partial downtime, (ii) applied part-time work alternatives, or (iii) offered variants of paid annual leave. Sometimes employers used combined strategies to retain jobs and associated personal income. In addition to job retention, businesses temporarily froze settlements with suppliers of services or goods; supply chains began to rupture. Due to the uncertain situation of virus control, domestic consumption temporarily shrank, and the content of the population’s basket of goods changed, giving priority to basic goods and services. Fluctuations in the balance between the supply demand of goods and services began.

During the first stage of pandemic management, countries published successive plans of measures to stimulate the economy and mitigate the effects of COVID-19, differing in content and the amount of funding, but similar in their main directions: (i) providing the resources needed for the health and public protection system to function efficiently, (ii) helping to safeguard jobs and the income of the population (downtime compensation mechanisms, unemployment benefits), (iii) helping businesses to maintain liquidity (deferral or compensation mechanisms for current liabilities, algorithms for granting soft loans, guarantees, and subsidies), (iv) stimulating the national economy, and (v) ensuring the liquidity of the state treasury.

1.1. Components That Define Efficient Management of Socio-Economic Recessions

Since the first stage of COVID-19 spread prevention management and the related lockdown regimes came to an end, an increasingly frequent question arises regarding which country’s COVID-19 control mechanism was the most efficient and effective in terms of its content and applicability. However, the question remains open. Researchers and experts, both those who analyse the socio-economic impact of COVID-19 on natural persons and legal entities in the country and those who focus on the tools for stabilising the economy during a recession, tend to arrive at different conclusions.

Researchers Mintron and O’Connor [8] argued that the efficiency of managing the negative consequences of the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic depends on timely and clear communication between the government and its subordinate institutions and the citizens of the country. Through proper communication, natural persons and legal entities can correctly interpret the government’s steps aimed at preventing the spread of the virus as well as the essence of socio-economic measures intended to help the businesses affected by COVID-19. According to the insights of the abovementioned authors, the quality of communication within the country greatly depends on the competence and leadership qualities of politicians. In this case, it can be assumed that the ranking of a politician in the country is no less important—the more the country’s citizens trust the political actor, the more likely it is that the positioning of the content of the disseminated information is stronger. Similar views are held by researchers Blackburn and Ruyle [9], who added that both the government’s communication with the country’s citizens and the content of all strategic steps must be composed in collaboration with scientists and experts in their fields.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) experts [10] also emphasised the importance of transparency in government action in order to implement economic measures as efficiently as possible to support natural persons and legal entities affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. In this case, businesses are properly informed about what preferential aid measures are offered and taxpayers know where their taxes are invested, and various countries are able to benefit from other countries’ best practices and researchers, make comparative insights, and provide algorithms for resolving similar situations in case they occur in the future.

The country’s experience and degree of development are important in dealing with unforeseen situations in managing socio-economic recessions. This view is shared by Ghosh et al. [11], who argued that developed countries are more effective in managing economic recessions than developing countries. A country that has struggled with economic downturns more than once has, in most cases, already established crisis management and economic stimulus mechanisms, the effects of which have been tested in previous recessions. The speed and quality of the response also depend on the state’s experience in combating economic recessions. The authors added that developing countries face two main shocks in the wake of an economic recession: (i) gradual, or sometimes sudden, stagnation of foreign capital inflows due to sudden austerity policies in relevant countries, and (ii) a possible significant decrease in export volumes due to declining foreign consumer demand for domestic goods. It is therefore very important to have plans for overcoming economic crises, and this is especially true for developing countries.

In their analysis of the economic crises that have occurred in the United States and the mechanisms for managing them, researchers Blinder and Zandi [12] argued that the first step in tackling a weakening economy is to stabilise the financial system, as credit is a vital financial tool in rescuing national economy. According to them, the greatest efficiency in managing an economic recession in a country is achieved by seeking a balance between fiscal and monetary policies. In this step, it is important that the economic measures proposed and applied interact with each other, i.e., complement rather than contradict each other. They proposed reducing the burden on taxpayers through temporary reductions in tax rates and optimisation of the government’s non-essential spending. The competence of policymakers is important, as mistakes can only be avoided if state aid is channelled where it is really needed, after pre-modelling the potential economic effect of the economic measure being initiated. Moreover, before the economy is stabilised, policymakers must not stop the tools of economic stimulus instead of moving abruptly to aggressive austerity. Blinder and Zandi [12], as well as Mintron and O’Connor [8] and Blackburn and Ruyle [9], argued that timely and high-quality cooperation with the public is an integral part of managing any economic crisis. Other researchers [11,13,14,15] emphasised that governments’ economic policy tools and the efficiency of their implementation depend on the historical state of the monetary and fiscal policies in the country when the crisis starts, and in the event of an economic crisis or recession, governments need to restructure the private sector balance, including the financial sector, while simultaneously raising domestic consumption levels, which have a long-term negative impact on government debt levels.

Most often, when an economic shock occurs in a country, policymakers try to restore the balance between supply and demand in the country [16] Some researchers [17,18] argued that the first COVID-19 lockdown had the greatest impact on the supply of products and services and that governments should have taken this into account when formulating economic stimulus and economic aid measures. Other experts [19] believed that the first lockdown was a greater shock to the demand for goods and services. However, over time, it has become increasingly common to believe that COVID-19 has had the same effect on both the supply and demand of goods and services, as restrictions on some businesses have affected production volumes and supply chains, whereas individuals affected by downtime or having lost their jobs and regular monthly income have had to adjust their shopping baskets and, in particular, reduce expenses on non-essential goods and services. The supporters of this view believe that economic measures to support COVID-19-affected natural persons and legal entities must include restoring the balance between supply and demand [20,21].

During the first stage of COVID-19 management, Elgin et al. [22] analysed the economic measures taken by 166 countries in response to the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and, in accordance with the data of 31 March, 2020, created a comprehensive database of key indicators of said countries’ fiscal and monetary policies. By means of principle component analysis, they developed the COVID-19 Economic Stimulus Index (CESI), which demonstrated that the content of national economic stimulus and COVID-19 mitigation plans depended on (i) the degree of development of the country, (ii) the age of the population, and (iii) the number of hospital beds in the country. The largest and strongest aid packages during the first stage of COVID-19 management were mostly offered by richer countries with older populations and fewer hospital beds.

Upon summarising and systematising the researchers’ insights into the negative consequences caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and economic recessions independent of the COVID-19 pandemic and presenting them in Table 1, we identified the main components defining efficient management of socio-economic recessions: the competence of policy makers as well as high-quality content of the initiated political action and its timely and transparent implementation.

Table 1.

Systematised scientific insights into the components of effective management (i) of the negative consequences caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and (ii) of economic recessions caused by other reasons.

1.2. Uncertainty in the Estimation of Efficiency

In their insight into the principles of policymaking and the estimation of their efficiency, Jacob et al. [23] argued that the principle must be developed on a case-by-case basis and for each estimated policy measure, as the same problem may be addressed in different ways. For example, in one country, there could be an active promotional campaign to reduce CO2 emissions and control environmental pollution, forcing businesses to think responsibly and reorganise production principles; other countries, in order to solve the same problem, may impose fines on businesses for exceeding the permissible levels of pollution; and still other countries may decide to actively subsidise the reorganisation of production, which would automatically reduce CO2 emissions. Which of these methods is the most efficient is an open-ended question that depends on the evaluator’s approach and the identification of evaluation elements that defined efficiency. The abovementioned authors emphasised that the level of corruption in the country, weak control over the implementation of the measure, and the cost and time of the implementation of the measure itself are elements that possibly reduced the final efficiency of the measure.

Similar views were shared by researchers Elgin et al. [21], who analysed packages of economic measures to support the lockdown-affected businesses and populations in 166 countries during the first stage of the spread of COVID-19. After standardising the data obtained, the authors concluded that during the first stage of COVID-19 lockdowns, the largest packages were mostly offered by richer countries. According to their estimates, Japan’s response was one of the most aggressive, with the expenditure package accounting for about 20% of the national GDP; in the USA, the aid package accounted for about 14% of GDP; in Australia, for 11% of GDP; in Canada, 8.4% of GDP; in the United Kingdom, 5% of GDP, etc. However, according to the authors, it would be incorrect to equate the size of the aid package as a share of the national GDP with its effectiveness or efficiency, because the essence was not the quantitative expression but rather the qualitative expression—the content of the economic measures and their interaction. The origin of the funding of the aid package, i.e., the ratio of the debt to one’s own capital, also mattered. Other examples include the volume and content of the downtime subsidy mechanisms, basically applied by all countries. The Netherlands presented one of the most generous downtime compensation plans, compensating employers for up to 90% of the employee’s wage-related costs, whereas the French government covered up to 84% of the employee’s gross wage costs and 100% when the employee received minimum wage. The UK government reimbursed up to 80% and the Canadian government up to 75% of gross monthly salary for up to three months. The USA took a different approach and offered businesses loans worth more than USD 650 billion, which did not have to be repaid, provided the companies were able to retain the number of employees they had been before the announcement of the lockdown regime in the country and spent most of the loan funds on salaries within two months of receiving the loan.

Schwartz et al. [24] and Jacob et al. [23] stated that measuring efficiency when the case did not have an accurate calculation methodology based on mathematical–statistical principles was a vague matter and in many cases advised the development of individual efficiency measurement algorithms. Researchers analysed the change in efficiency measuring of the investment in research and development (R&D), and simultaneously in related new products and services, and carried out a comparative analysis of the results of the quantitative and qualitative surveys of business representatives in 1994 and 2009; they concluded that the prioritisation of indicators determining the efficiency of investment in R&D changed over time and new elements of evaluation appeared. Moreover, the authors argued that in order to measure the efficiency of a particular object or factor as accurately as possible, it is necessary to measure it by comparing business entities within the same economic sector and even, wherever possible, those with the same strategic goals.

1.3. Characteristics of the Concept of Efficiency

The concept of efficiency is an integral part of economics, management, engineering, and political and other sciences. The concept itself is thought to have originated from the Latin word efficientia, which in the original interpretation from 1630 meant “the degree of ability to do something.” Lukaševičius et al. [25] described efficiency as the level of resource utilisation that guarantees maximum results. Mackevičius [26] added that the more efficiently resources are used, the faster the products are produced and sold.

Normand [27] and Newbold [28] argued that economics itself is a science of scarcity and choice that aims to select out of a large number of limited, competing resources and distribute them in a way that best meets the needs of society. Newbold [28] and Lukaševičius et al. [25] described efficiency as the situation where the production costs of any output are minimal and the benefits and value are maximal. Newbold [28] argued that three main interpretive algorithms for efficiency can be identified: technical, allocative, and social efficiencies.

Technical efficiency means that the most efficient option is the one that achieves the result at the lowest cost and creates the highest added value when comparing different alternatives through cost-benefit ratios. Technical efficiency is calculated on the basis of a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA). It is proposed to calculate and analyse at least two different alternatives and to choose the lowest cost-generating option.

Allocative efficiency means that there are always gains and losses, and it is not possible to make one member of society happy without making another one unhappy. This efficiency is analysed through a cost-utility analysis (CUA) and the option where quality is achieved at the lowest cost is selected and funded. However, the lowest cost does not always predetermine the condition for creating the best added value: E.g., the more the government invests in quality medical care programs, the better medical services the public receives and the better the content, and even the duration, of life is. However, programmes of this type require higher investments and automatically higher budget expenditures; therefore it is important to allocate the funds planned for the respective programme as efficiently as possible.

Social efficiency means that the benefits accruing from the losses incurred must be maximal, and the losses incurred must be compensated for by the highest possible added value created by the product or service. This principle is calculated on the basis of a cost-benefit analysis (CBA), which assesses the maximum price that the consumer is willing to pay for the benefits of the purchased product or service.

In summary, efficiency can be defined as a degree of cost-benefit comparison. Efficiency is often equated with effectiveness and is always associated with the quantitative or qualitative measurement of the goal or result achieved. Quantitative measuring of efficiency is performed on a mathematical basis by applying and testing different models of mathematical analysis and comparing tangible, i.e., quantifiable, indicators. A qualitative efficiency measurement algorithm is usually developed on a case-by-case basis. When evaluating efficiency, it is important to determine the criteria according to which the result is measured and selected as well as the priorities of the initiator of the efficiency evaluation: whether to achieve the set quality of the final product or provided service at the lowest cost, or whether to achieve the best quality of the product or service provided at rational, but not the lowest, cost.

2. Materials and Methods

The current paper applies a synthesis of two data processing techniques of the theoretical research methods: (i) secondary data collection, analysis, comparison, systematisation, and aggregation techniques and (ii) a modelling technique intended to structure the results obtained during the secondary data collection and analysis, and to visualise the components for measuring the efficiency of the impact of the Lithuanian government’s economic interventions on business during the first lockdown.

According to Tidikis [29], modelling is the disclosure of the relationships and behaviour of certain objects, object systems, or processes by means of the development and exploration of models. The model of the research object reflects a system of material or ideal elements or their combination and reproduces the structural–functional, cause–effect, and genetic connections between the elements of the object in question [30]. Thus, a model is a simplified representation of a real object, process, or phenomenon, recreating the relationships, structure, and functions of a particular phenomenon. This paper develops a theoretical model of the components for measuring the efficiency of the impact of the Lithuanian government’s economic interventions on business during the first lockdown.

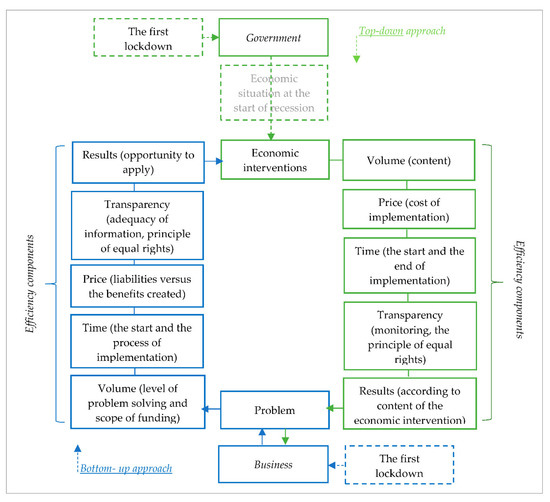

In the paper, we propose estimating the principle of evaluating the efficiency of the Lithuanian government’s economic measures intended to support businesses that encountered difficulties due to the first lockdown in accordance with the main components and logic, visualised in the conceptual model below. It should be emphasised that the analysis of the quality of the government’s action and the efficiency of the selection of business support measures was based on the principle of winners and losers: All the State financial support was limited merely to directly COVID-19-affected businesses whose activities were totally or mainly restricted due to the content of the lockdown regime and that were included in special victim lists of the State Tax Inspectorate due to their operation restrictions; most of the funds were directed to rescue Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). Businesses that experienced an indirect adverse impact of the lockdown and whose activities were not restricted by the content of the lockdown regime had to prove it individually. We assumed that the government’s goal was to help businesses survive during and after the first lockdown at the lowest possible cost. In this case, we saw the logic of the principle of allocative efficiency: Additional and unplanned expenditures of the State budget and borrowing limits were regulated, and the funds to support businesses affected by the first lockdown were rationally allocated. From a business point of view, the efficiency of the government’s proposed aid package depended on the short-term benefits of those measures for business and on whether, after analysing the content of the proposed economic measures, businesses were willing to make commitments at a time that was tough for them as it was.

3. Results

Upon analysing and systematising researchers’ insights into the main factors both making it possible to most effectively manage socio-economic recessions and to successfully prevent the spread of COVID-19 and help natural persons and legal entities to survive during and after the lockdown, we generated a theoretical model; it aimed to visualise a principle for measuring the efficiency of the economic measures implemented by the Lithuanian government during the first lockdown to support COVID-19-affected businesses, in accordance with the main components reflecting it: volume, price, time, transparency, and results. In this case, the efficiency must be measured in accordance with the approaches of (i) top-down and (ii) bottom-up (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A model for measuring the efficiency of the economic measures implemented by the government during the first lockdown.

The top-down approach means that the efficiency of an economic measure is measured from the initiator of the measure (i.e., the government or its subordinate institutions) to its beneficiary (i.e., legal entities). In this case, the government has to answer the key question: Has the implementation of interventions solved the problems that have developed in the country? Measuring the efficiency of an intervention on a top-down basis, i.e., from its initiator, covers:

- —

- Volume: the descriptive part of the measure and the scope of funding for the solution of the problem, i.e., content;

- —

- Price: the costs required to initiate and implement the measure;

- —

- Time: the period of initiation and implementation of the measure;

- —

- Transparency: control of the implementation of the measure, ensuring the principle of equal rights; and

- —

- Results: the tools for measuring results raised in the content of the measure and the results to be achieved.

The bottom-up approach would make it possible to measure the actual impact of an economic measure on business by measuring the efficiency from the beneficiary of the measure (i.e., a legal entity) to the initiator of the measure (i.e., the government or its subordinate institutions). In this case, the business entity has to answer the key question: Do they find the initiated economic measure efficient for them? Measuring the efficiency of an intervention on a bottom-up basis, i.e., from its recipient, covers:

- —

- Volume: the adequacy of the content and the scope of funding of the measure for the solution of the problem;

- —

- Time: the period of processing the measure “from–to,” the fluency and clarity of the process;

- —

- Price: the ratio of short-term or long-term commitments to be made as necessary for the implementation of the measure to the benefits received;

- —

- Transparency: transparency and sufficiency of information about the implemented measure, ensuring the principle of equal rights; and

- —

- The result: the possibility for the business entity to use the analysed measure.

The synergy and combination of the two approaches best measures the efficiency of an economic measure, which is recommended to be compared and measured in terms of responses from businesses in the same economic sector and of similar size. The efficiency of the interventions initiated by the Lithuanian government during the first lockdown are measured in the general context in the section below.

4. Discussions

The Government of the Republic of Lithuania responded very quickly to the extent of the COVID-19 global spread and the threats it posed to human health and life. The government, in response to both the growing number of COVID-19 infections in the country and in order to align its strategies with other EU member states seeking to halt the spread of the virus, on 26 February, 2020 declared a public health emergency across the country [31]; on 16 March, 2020, a lockdown regime and a third (full readiness) level of civil protection system was announced in the territory of the Republic of Lithuania [32]. The first lockdown regime continued from 00:00 hrs. of 16 March, 2020 until 24:00 hrs. of 16 June, 2020 [33].

During the first lockdown, the following activities were banned in the territory of Lithuania [34]:

- —

- Activities of education institutions, day care, and employment centres;

- —

- Visiting cultural, leisure, entertainment, or sports facilities, and physical service to visitors. Organisation of events and gatherings in open and closed spaces;

- —

- Provision of beauty and wellness services;

- —

- Activities of mass caterers, restaurants, cafes, bars, and other places of entertainment, except where food could be taken away or otherwise delivered to the public;

- —

- Operation of shops and shopping and entertainment centres, except for food, veterinary, and optical shops and pharmacies; and

- —

- Arriving in and leaving the country.

In accordance with the government’s response to the COVID-19 Government Stringency Index (GSI) [35], which is calculated on the basis of restrictions on the activities of legal entities and natural persons during the lockdown regime (restrictions on freedom of movement, education, and event organisation; organisation of public information campaigns; etc.), Lithuania was rated with 68.52 points (the measurement covered 0 to 100 points, where 100 points indicated a very strict lockdown regime). For comparison, in Latvia the indicator was 57.41 points, and in Estonia, 29.63 points. Therefore, we can argue that the regime of the first lockdown in Lithuania was quite strict and was close to that of the EU member states applying strict lockdowns, such as Poland (71.3 points), Spain (71.3 points), or France (78.7 points). The content (strength of restrictions) and duration of the lockdown had a direct impact on the socio-economic shock in the country.

4.1. Volume

4.1.1. A View of the Initiator of the Measure

On 16 March 2020, the Government of the Republic of Lithuania undertook immediate implementation of a short-term “Plan of Measures to Stimulate Economy and Reduce the Consequences of the Spread of Coronavirus” [36] in order to help solve the problems of maintaining businesses’ financial liquidity and personal income [3]. Said strategic plan to address short-term challenges was initiated promptly and presented on the first day of the lockdown. Although the content of the plan was continually updated, the basic principles remained the same: (i) to ensure the resources needed for the health and public health system to function effectively, (ii) to help preserve the jobs and the income of the population, (iii) to help businesses maintain liquidity, (iv) to stimulate the national economy, and (v) to ensure the liquidity of the state treasury. The economic stimulus plan approved on 16 March 2020, provided for the total amount of funding for the government measures—EUR 2.5 billion, and the total volume of measures, together with the lending potential of financial institutions—EUR 5.782 billion, or 10% of the national gross domestic product (GDP). Moreover, the plan provided for the government being allowed to borrow at least EUR 5 billion and for the expansion of the municipal borrowing rights.

In essence, interventions in all countries as a response to the adverse socio-economic consequences of the lockdown regime could be divided into three main categories [13]:

- (1)

- Immediate additional government expenditures (promoting people’s employment and maintaining jobs, subsidising SMEs) and lost revenue—abolition of certain State taxes.

- (2)

- Automatic deferral of payments—deferral of certain taxes allocated to the State and their refund in accordance with a schedule agreed in advance with the State institutions. Said measures improved the solvency situation of natural persons and legal entities in the short term, but did not withdraw their obligations in the future.

- (3)

- Other liquidity-improving measures—those measures were an individual choice of each business entity (individual, portfolio, or export guarantees; soft loans). In the short term, the measures improved the liquidity of the business entity, but created additional liabilities in the future.

In the case of Lithuania, preferential support was available to business entities that had experienced a direct negative impact of the lockdown regime and were included in the list of affected companies publicly presented by the State Tax Inspectorate (LR VMI, by its initials in Lithuanian) [32]. Moreover, the main focus was on the restoration of the financial condition of small- and medium-sized businesses: Downtime, loan interest, and commercial rent compensation mechanisms; subsidies for micro-enterprises; and soft loans without collateral and individual and portfolio “Investicijų ir verslo garantijos”, Ltd. (Investment and Business Guaranties) (INVEGA, by its initials in Lithuanian) [37] guarantees were proposed. All taxes to be paid to State institutions (wage-related, utility taxes, value added taxes) could be deferred, and deferred tax refund schedules could be established.

4.1.2. A View of the Beneficiary

The fact that the “Plan of Measures to Stimulate Economy and Reduce the Consequences of the Spread of Coronavirus” [36] was initiated on the first day of the lockdown did not mean the quality of its content. Thus, Germany, which had experience in managing economic recessions, announced its economic plan as late as 25 March 2020, although the first virus control mechanisms were launched as early as at the end of February 2020, and the financial package amounted to as much as EUR 750 billion, about 23% of the national GDP.

Many of the economic measures included in the economic stimulus plan were based on co-financing (excluding the measures of interest compensation and subsidies to micro-enterprises) or borrowing. That meant that the business had to contribute, at least in part, to the relevant costs or make commitments (to take loans) during a sensitive period when the demand in the country had fallen due to people’s fears of a second wave of COVID-19 or loss of income due to downtime or the loss of jobs during the lockdown or at the end of it. Moreover, State institutions’ taxes on business were not abolished; they were only deferred, which meant that tax debts accumulated. In addition, Lithuania in a global context was considered as a country that “weakly” implemented deferrals of commitments (utilities, VAT, the State Social Insurance Fund (SODRA, for its initials in Lithuanian) taxes). For example, Latvia and Estonia were considered countries that offered a broad package of automatic deferrals [35].

During the first lockdown, companies included in the LR VMI list of COVID-19-affected companies were eligible for State support, provided that their activities were directly terminated or restricted due to the lockdown [32], without taking into account the possible indirect negative effects of COVID-19. Entrepreneurs who did not find themselves on the abovementioned lists, but who also suffered negative consequences due to COVID-19, could apply to the LR VMI for support measures for their business with an application in a simplified form to justify the negative consequences of the first lockdown; the rule, however, did not always take effect. Only at the beginning of the second lockdown, i.e., from 4 November 2020, Resolution of the Government of the Republic of Lithuania No. 1226 “On the Announcement of Lockdown in the Territory of the Republic of Lithuania” [38] identified both direct and indirect negative effects of the lockdown on business.

The situation of quite a few enterprises whose activity was not restricted during the lockdown regime and that were not included in the list of affected enterprises by the LR VMI had deteriorated due to the uncertainty of the economic environment and of the situation in the country; the closure of borders complicating the movement of goods; ruptured supply, production, and marketing chains; stagnant settlements; and reduced sales flows. In accordance with the official statistics, from March 2020, the sales flows of non-assisted companies fell sharply, and only towards July 2020 did they reach at least the level of sales flows of July 2019 [39].

4.2. Price

4.2.1. A View of the Initiator of the Measure

All economic measures detailed in the “Plan of Measures to Stimulate Economy and Reduce the Consequences of the Spread of Coronavirus” [36] were implemented and controlled by responsible institutions. Thus, the Ministry of Social Security and Labour of the Republic of Lithuania, for example, was responsible for maintaining jobs and income, and the Employment Services under the Ministry of Social Security and Labour compensated employers for the costs incurred due to employee downtime, and took care of quality integration of the unemployed into the labour market. The State Tax Inspectorate under the Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Lithuania provided subsidies to micro-enterprises affected by the lockdown, and the major and main part of the economic measures intended to restore business liquidity was curated by INVEGA [37] under the Ministry of Economy and Innovation of the Republic of Lithuania.

4.2.2. A View of the Beneficiary

But for the global COVID-19 pandemic as well as the declared emergency and the lockdown regime in Lithuania, each business would have likely continued to operate in accordance with its usual algorithm of activity formation and organisation: It would have planned sales and raw material purchase ratios and potential turnover, would have regulated the number of employees, and would have monitored potential opportunities for business development and optimisation. With the onset of the lockdown in the country and the partial or total restriction of many businesses, business, through no fault of its own, faced a shortage of working capital to (i) pay wages and all related taxes, (ii) cover the costs of rent of commercial premises and related utilities, (iii) settle accounts with suppliers of goods and services, etc. However, in “rescuing” business, the government in many cases forced it to make commitments to (i) partially compensate for downtime subsidies and commercial rent, (ii) assume the obligations arising out of the loans, and (iii) independently cover the debts of accrued taxes to State institutions, etc.

4.3. Time

4.3.1. A View of the Initiator of the Measure

The “Plan of Measures to Stimulate Economy and Reduce the Consequences of the Spread of Coronavirus” [36] was presented by the government with particular urgency, as early as on the first day of the lockdown regime, i.e., on 16 March 2020, and the first tangible economic measures were initiated and implemented from the beginning of April 2020. In principle, all economic measures were implemented until 31 December 2020, and only the measures for which the planned basket had been used up faster than planned were suspended earlier.

4.3.2. A View of the Beneficiary

Quite a few economic measures intended to help the businesses affected by COVID-19 were adopted as the lockdown gained momentum, meaning that businesses had to cover the running costs on their own. Thus, downtime compensation, for example, was received by the employer only after the employees had been paid salaries and after submitting a request to Employment Services under the Ministry of Social Security and Labour of the Republic of Lithuania to partially compensate for the costs incurred due to downtime payouts. The first applications for downtime payout compensation could be submitted by employers no earlier than on 5 April 2020. Moreover, the mechanism for reimbursing the rent for commercial premises came into force only on 4 May 2020, which meant that before that date, businesses had to cover the rent with their own funds, and with the entry into force of the measure, the landlord of commercial real estate had to lose up to 30% of the lease value in order for the lessee to receive support from the State. Any belated response from the government and the proposed measure could have led to irreversible changes in the economy. For that reason, many businesses that were fully or partially restricted and that had no alternatives (such as e-commerce or home delivery) were forced to suspend operations orlay off all existing staff. In accordance with official statistics, compared to 16 March 2020, i.e., the beginning of the first lockdown in Lithuania, when the unemployment rate in the country amounted to 9.3% (or 160,454 individuals), by 11 November 2020, the unemployment rate had risen to 15.1% (or 259,888 individuals) [40]. The growth of the unemployment rate in the country showed the inability of companies to maintain jobs after the end of the lockdown, even with the State support intended to preserve jobs and the income of the population.

Moreover, not only was the start of the implementation of many economic measures belated, but also after meeting the requirements of the measure and signing all the documents required for the implementation of the measure, businesses could wait for money up to three months, especially in the case of soft loans. In addition, due to the lack of human resources, the implementation of measures at INVEGA was stalled and delayed.

The government commented on the reason for the “wait” for economic measures as early as at the beginning of the first lockdown by arguing that “something must be wrong” with a business that encountered difficulties after the first month of the lockdown. However, back in 2016, a study by the JPMorgan Chase Institute [41], based on the data of nearly 600,000 USA small businesses and focusing on the money stocks accumulated by companies operating in certain sectors of the economy, showed that a company’s “survival” time depended on the area of activity and even on size. Labour-intensive sectors (which accounted for the majority of service-providing enterprises, particularly affected by lockdown restrictions) had the smallest cash reserves: catering enterprises for 16 days, repair and maintenance enterprises for 18 days, retail enterprises for 19 days, and construction companies for 20 days. The conclusion followed that an average small business could survive without income for up to 27 days, and only 25% of all companies were able to survive for more than two months.

4.4. Transparency

4.4.1. A View of the Initiator of the Measure

The government representatives argued that all the implemented economic measures were strictly controlled by the competent institutions implementing them and that all the implementation processes took place in accordance with the conditions provided for in the content of the measure and the principle of equal rights. All information on the economic measures implemented by the government was published on its official website: https://koronastop.lrv.lt/lt/pagalba-verslui, as well as on the official websites of other institutions responsible for the implementation of the respective measures.

Moreover, in order to ensure effective communication between State institutions and the public, on 18 May 2020, a “Covid-19 Management Strategy Communication Plan” [42] was approved, allocating funds to governmental institutions for publicising the interventions being implemented: (i) EUR 50,000 to the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Lithuania for the dissemination of information on cultural policy changes related to COVID-19 consequences, (ii) EUR 75,000 to the Ministry of Social Security and Labour of the Republic of Lithuania for the dissemination of information to people who had lost their jobs due to COVID-19, and (iii) EUR 50,000 to the Ministry of Education, Science and Sports of the Republic of Lithuania for publicising information on changes in the educational process and sports, etc.

4.4.2. A View of the Beneficiary

From the first days of the lockdown, businesses faced a lack of clear and high-quality Government communication: It was not clear on what principle the operating losses would be restored. When drawing up the “Plan of Measures to Stimulate Economy and Reduce the Consequences of the Spread of Coronavirus” [36], the government did not consult with business associations, which were asked to make commitments during a very uncertain period in the country. The support measures were accompanied by irrational requirements, additional conditions, and the resulting administrative burden. There were cases where the applying business entity was refused support even though it met all the requirements of the measure.

4.5. Results

4.5.1. A View of the Initiator of the Measure

The government measured the efficiency of the implemented economic measures in terms of the direct and indirect effects created by them. However, it is important to measure not only the solution of the target problem, but also the added value created by this solution. The results of the implemented measure were measured through the reports prepared by the institutions implementing it as well as the data published by the Department of Statistics, which made it possible to assess how the situation of the supported business had changed.

During October 2020, the government was scheduled to raise up to EUR 782 million in budget revenue: EUR 757 million were received, and the difference amounted to EUR 25 million. Said difference in the planned/received revenue from March 2020 was the smallest (the difference between planned and received revenues in the budget in March 2020 was EUR −96 million, in May 2020 EUR −253 million, and in July 2020 EUR −111 million). In the period between March and July 2020, 361 companies were registered with a bankruptcy status, i.e., 50 percent less than in the same period in 2019, when 728 bankruptcies were registered [40].

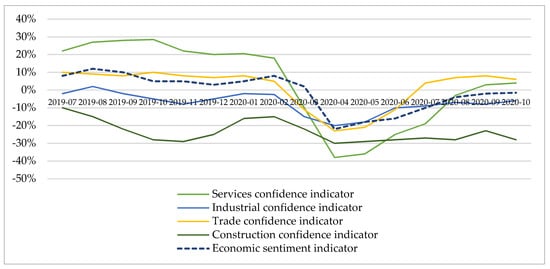

The changing “pulse” of the Lithuanian economy and the confidence of natural persons and legal entities in the national economy were measured with sufficient accuracy through the indicator of economic assessments (Figure 2). Said indicator measures the state of the main economic actors—consumers and the sectors of industry, construction, trade, and services—as well as the degree of confidence in the national economy. Sector confidence indicators are obtained by interviewing the managers or representatives of the enterprises of respective sectors in accordance with the assessments made for that sector (assessment of the level of demand for manufactured goods and services, assessment of the level of stocks of manufactured products, etc.), deriving an arithmetic weighted average.

Figure 2.

Economic sentiment indicator and its components, by percent [43].

When analysing the level of confidence of the main economic sectors in the national economy and related government resolutions, we found out that before the beginning of the spring lockdown of 2020, representatives of the industry and construction sectors had a negative view of the economic stimulus tools implemented by the government. The service and trade sectors, on the contrary, had a fairly stable and strongly positive view of the national economy. With the start of the first lockdown, the biggest decline in confidence was observed in the service sector, and there was a significant change in the trade sector. Representatives of the trade and service sectors were the businesses most affected by the activity restrictions imposed by the first lockdown regime. It was observed that compared to the sharp fall in March 2020, from May 2020 onwards the view of the national economic situation in all analysed economic sectors started to improve, which may have coincided with the government’s successive economic measures intended to help COVID-19-affected businesses.

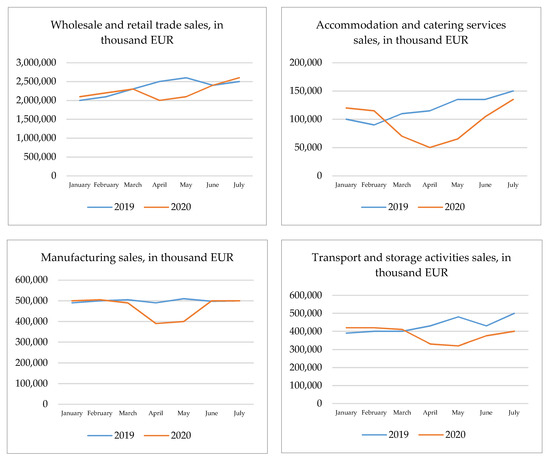

The stabilisation of sales flows in wholesale and retail trade, manufacturing, accommodation, and catering services sectors showed the recovering purchasing power of domestic consumers, which was improving due to the stabilisation of the national economy and the preservation of jobs, and simultaneously of income (Figure 3). A slower, yet positive, recovery in sales was observed in the transport sector.

Figure 3.

Trends in sales flows by economic sector, in thousand EUR [39].

In April 2020, the business development company FM Global [44] introduced the Global Resilience Index (GRI), which, according to the company, can measure a country’s resilience to unforeseen factors. The index ranked 130 countries according to the level of relevant factors assessed in the country: (i) economic and political stability of the country, (ii) ability of business leaders to respond to force majeure situations, (iii) transparency of the business environment, and (iv) organisation of goods and services supply chains. The final score of the index was expressed in points and measured on a scale of 0 to 100, where 0 represented the lowest resistance and 100 the highest. In accordance with the above-mentioned index, Lithuania ranked 34th in the world, which showed a strong level of resilience to unforeseen factors in the country. By comparison, Estonia ranked 30th and Latvia 39th.

4.5.2. A View of the Beneficiary

The weak efficiency of the implementation of the government’s economic measures is indicated by statistical data:

- −

- By 26 November 2020, only 49.4% of all the funds provided for in the “Plan of Measures to Stimulate Economy and Reduce the Consequences of the Spread of Coronavirus” [36] had been used [40].

- −

- From 5 April 2020, i.e., the start of initiation of the subsidies for downtime, until 27 September 2020, i.e., before the start of the second lockdown, 73,305 companies applied for subsidies as compensation for downtime payouts (a total of 506,224 jobs were to be compensated) and only 24,129 applicant companies received them (i.e., only 201,439 jobs were reimbursed by the State). In other words, 33% out of 100% applications were accepted [40].

- −

- On 1 September 2020, in almost all economic sectors, and in the period from 11 March 2020 to 1 September 2020, a negative increase in staff was observed, i.e., the companies that had received compensation for downtime still had to lay off part of their staff [39]. From the beginning of the first lockdown, i.e., 16 March 2020, until 27 September 2020 (before the start of the second lockdown), the number of the unemployed in the country increased from 9.3% (i.e., 160,454 individuals) to 14.1% (i.e., 243,403 individuals), and accounted for a 4.8% increase.

- −

- From 16 March 2020, i.e., the start of the first lockdown, until 1 September 2020, about 21% of the companies registered in Lithuania suspended tax payments to the State Tax Inspectorate (on 26 November 2020, i.e., after the second lockdown had already started, the indicator increased to 43%), and 19% of the companies registered in Lithuania suspended the payment of taxes to SODRA [39].

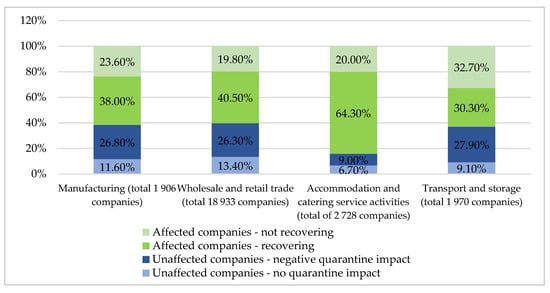

In accordance with the taxes paid to the State Tax Inspectorate, on 1 September 2020, a rather large share of companies in key economic sectors never recovered after the first lockdown (Figure 4). Moreover, companies not directly affected by the first lockdown regime began to feel indirect negative effects of the lockdown over time. The best recovery after the lockdown regime was observed in the sector of accommodation and catering, but it happened not due to the efficiency of the government’s economic measures, but rather due to seasonality: the summer season.

Figure 4.

Dynamics of corporate recovery according to the impact of the first lockdown regime, by percent [39].

5. Conclusions

Upon analysing the efficiency of the Lithuanian government’s interventions with the aim of supporting business, initiated and implemented during and after the first lockdown, both from the point of view of the initiator of the measure and of the beneficiary, we can argue that the range of views differs. In accordance with the government’s view, the management of the negative consequences of the first lockdown was rich in various measures aimed at improving the dynamics of business recovery in the short term, and in this case the government’s actions were efficient: A relatively rational share of borrowed funds was assumed, and strategic documents for managing the negative consequences of COVID-19 were prepared promptly together with measures, the main beneficiary of which were SMEs. The aim was set to preserve as many jobs as possible, simultaneously with the income and purchasing power of the population, thus automatically maintaining the level of supply of goods and services in the country, etc. A publicity plan was provided for all government-initiated policy measures and resolutions during and after the first lockdown.

However, in assessing the policy of the government’s intervention measures in relation to their beneficiaries, the efficiency was insufficient. In particular, the government failed to assess the potential indirect adverse effects of the lockdown regime on businesses that were not subject to direct activity restrictions during the lockdown regime. Moreover, due to the lack of timely and clear communication, businesses made hasty decisions: They immediately laid off all or part of the staff and hastily tried to change the principles of business organisation, thus negatively affecting the well-being of the company. In applying for State support, in many cases businesses also had to contribute a corresponding percentage to the compensation mechanisms, even if their activities did not generate any income during the lockdown period, or to make commitments in the case of soft loans during the period of uncertainty in the country. In the event of a similar uncertainty in the future and a concomitant economic recession in the country, policymakers should consider that the activities of natural persons and legal entities were forcibly restricted by the State regulations, and therefore it would be worth taking this into account when generating the aid package content.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.N., R.V., and A.Š.; methodology, J.N. and R.V.; formal analysis, J.N. and I.A.; writing—original draft preparation, J.N. and R.V.; writing—review and editing, J.N. and R.V.; visualization, J.N.; supervision, J.N., R.V., A.Š., and I.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was published with research funding provided by the Lithuanian Science Council Grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available in a publicly accessible repository that does not issue DOIs. Publicly available datasets were analysed in this study. This data can be found here: [39,43].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Europos Vadovų Taryba [European Council]. Chronologija. Tarybos Veiksmai dėl Covid-19 [Chronology. Council Action due to Covid-19]. 2020. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/lt/policies/coronavirus/timeline/ (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Lietuvos Respublikos Seimas [Parliament of Lithuania]. Europos Sąjungos Valstybių Narių Kovos su Koronaviruso Pandemija Strategija ir Priemonės. Analitinė Apžvalga [Strategy and Measures to Combat the Coronavirus Pandemic in the Member States of the European Union. Analytical Review]; Parliament of Lithuania: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2020; pp. 23–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybė [The Government of Lithuania]. Covid-19 Valdymo Strategija [Covid-19 Management Strategy]; Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybė: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2020.

- Gensini, G.F.; Conti, A.A. The evolution of the concept of ‘fever’ in the history of medicine: From pathological picture per se to clinical epiphenomenon (and vice versa). J. Infect. 2004, 49, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, A. Quarantine Through History. Int. Encycl. Public Health 2008, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, A.A.; Gensini, G.F. The historical evolution of some intrinsic dimensions of quarantine. Med. Secoli 2007, 19, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gensini, G.F.; Yacoub, M.H.; Conti, A.A. The concept of quarantine in history: From plague to SARS. J. Infect. 2004, 49, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mintron, M.; O’Connor, R. The importance of policy narrative: Effective government responses to Covid-19. Policy Des. Pract. 2020, 3, 205–227. [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn, C.C.; Ruyle, L. How Leadership in Various Countries has Affected COVID-19 Response Effectiveness. Available online: https://theconversation.com/how-leadership-in-various-countries-has-affected-covid-19-response-effectiveness-138692 (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- OECD. Government Support at the Covid-19 Pandemic. Policy Responses to Coronavirus 2020. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/government-support-and-the-covid-19-pandemic-cb8ca170/ (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- Crowe, C.; Ostry, J.; Kim, J.; Chamon, M.; Ghosh, A. Coping with the Crisis: Policy Options for Emerging Market Countries. IMF Staff. Position Notes 2009, 2009, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Blinder, A.S.; Zandi, M. The financial crisis: Lessons for the next one. Cent. Budg. Policy Priorities 2015, 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.; Beramini, E.; Brekelmans, S. The Fiscal Response to the Economic Fallout from the Coronavirus. Available online: https://www.bruegel.org/publications/datasets/covid-national-dataset/ (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Claessens, S.; Kose, A.; Laeven, L.; Valencia, F. How Effective Is Fiscal Policy Response in Financial Crises? Available online: https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/IMF071/20264-9781475543407/20264-9781475543407/ch14.xml?language=en (accessed on 14 November 2020).

- Reinhart, C.M.; Rogoff, K. The Aftermath of Financial Crises. SSRN Electron. J. 2008, 14656, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Galindo, H. What kind of firm is more responsive to the unconventional monetary policy? Theor. Approach SSRN 2020, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bekaert, G.; Engstrom, E.C.; Ermolov, A. Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply Effects of COVID-19: A Real-time Analysis. SSRN Electron. J. 2020, 049, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornaro, L.; Wolf, M. Covid-19 coronavirus and macroeconomic policy. CEPR Discuss. Pap. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, M.F. Fiscal policy during a pandemic federal reserve bank of St. Louis. Work. Pap. 2020, 6, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrieri, V.; Lorenzoni, G.; Straub, L.; Werning, I. Macroeconomic Implications of COVID-19: Can Negative Supply Shocks Cause Demand Shortages? SSRN Electron. J. 2020, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiley, M.T. Pandemic Recession Dynamics: The Role of Monetary Policy in Shifting a U-Shaped Recession to a V-Shaped Rebound. Financ. Econ. Discuss. Ser. 2020, 2020, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgin, C.; Basbug, G.; Yalaman, A. Economic policy responses to a pandemic: Developing the Covid-19 economic stimulus index. Covid Econ. 2020, 3, 40–53. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, K.; King, P.; Mangalagiu, D. Approach to Assessment of Policy Effectiveness. Chapter 10. The Sixth Global Environment Outlook; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 274–281. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, L.; Miller, R.; Plummer, D.; Fusfeld, A.R. Measures of effectiveness of R&D. Res. Technol. Manag. 2011, 54, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Lukaševičius, K.; Martinkus, B.; Piktys, R. Verslo Ekonomika [Business Economics]; Technologija: Kaunas, Lithuania, 2005; p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- Mackevičius, J. Įmonių veiklos analizė: Informacijos rinkimas, sisteminimas ir vertinimas [The analysis of companies’ business as a system of collection, research and evaluation of information]. Inf. Moksl. 2008, 46, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normand, C. Economics, health, and the economics of health. Br. Med. J. 1991, 303, 1572–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Newbold, D. A brief description of the methods of economic appraisal and the valuation of health states. J. Adv. Nurs. 1995, 21, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tidikis, R. Socialinių Mokslų Tyrimų Metodologija [Social Science Research Methodology]; Lietuvos Teisės Universitetas: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2003; pp. 425–432. [Google Scholar]

- Kardelis, K. Mokslinių Tyrimų Metodologija ir Metodai [Research Methodology and Methods]; Lucilijus: Šiauliai, Lithuania, 2007; pp. 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybė [The Government of Lithuania]. Nutarimas nr. 152 “Dėl Valstybės Lygio Ekstremaliosios Situacijos Paskelbimo” [Resolution No. 152 On the Declaration of a State of Emergency]; Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybė: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2020.

- Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybė [The Government of Lithuania]. Nutarimas nr. 207 “Dėl Karantino Lietuvos Respublikos Teritorijoje Paskelbimo” [Resolution No. 207 On the Announcement of Quarantine in the Territory of Lithuania]; Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybė: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2020.

- Lietuvos Respublikos Sveikatos Apsaugos Ministerija [Ministry of Health of Lithuania]. Vyriausybės Sprendimu Atšaukiamas Lietuvoje Paskelbtas Karantinas [The Quarantine Announced in Lithuania Is Revoked by a Government Decision]. Available online: https://sam.lrv.lt/lt/naujienos/vyriausybes-sprendimu-atsaukiamas-lietuvoje-paskelbtas-karantinas (accessed on 19 October 2020).

- Lietuvos Respublikos Socialinės Apsaugos ir Darbo Ministerija [Ministry of Social Security and Labor of Lithuania]. Ką Daryti ir ko Nedaryti Darbdaviams Šalyje Paskelbus Karantiną? [What to Do and What Not to Do to Employers after Quarantine Ends in the Country?]. 2020. Available online: https://socmin.lrv.lt/lt/naujienos/ka-daryti-ir-ko-nedaryti-darbdaviams-salyje-paskelbus-karantina (accessed on 14 October 2020).

- Ritchie, H.; Beltekian, D.; Edouard, M.; Hasel, J.; McDonal, B.; Roser, M. Policy Responses to Coronavirus Pandemics. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/policy-responses-covid (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybė [The Government of Lithuania]. Ekonomikos Skatinimo ir Koronaviruso Plitimo Sukeltų Pasekmių Mažinimo Priemonių Planas [Plan of Measures to Stimulate the Economy and Reduce the Consequences of the Spread of Coronavirus]; Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybė: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2020.

- Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybė [The Government of Lithuania]. Nutarimas Nr. 887 “Dėl Smulkaus ir Vidutinio Verslo Plėtros” [Resolution no. 887 Development of Small and Medium Business]; Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybė: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2001.

- Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybė [The Government of Lithuania]. Nutarimas nr. 1226 “Dėl Karantino Lietuvos Respublikos Teritorijoje Paskelbimo” [Resolution no. 1226 On the Announcement of Quarantine in the Territory of Lithuania]; Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybė: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2020.

- Valstybinė Mokesčių inspekcija prie Lietuos Respublikos Finansų ministerijos [State Tax Inspectorate under the Ministry of Finance of Lithuania]. Pagalba dėl Covid-19 Nukentėjusiems Juridiniams Asmenims [Assistance to Legal Entities Affected by Covid-19]; Valstybinė Mokesčių Inspekcija Prie Lietuos Respublikos Finansų Ministerijos: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2020.

- Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybė [The Government of Lithuania]. Informacija Apie Ekonomikos Skatinimo Plano Priemonių Įgyvendinimą [Relevant Information about Coronavirus]. 2020. Available online: https://koronastop.lrv.lt/lt/pagalba-verslui?fbclid=IwAR08C12a4S0ZNt1R_g7FqQ2tbE83r5z-vDxgBTFDhhwcs94vJIGu5RcIN7Q (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- JPMorgan Chase and Co. Small Business Cash Buffer Days Vary Across Metropolitan Areas, But no Clear Pattern Emerges from Variance. Cash Is King: Flows, Balances and Buffer Days 2016. Available online: https://www.jpmorganchase.com/institute/research/small-business/report-cash-flows-balances-and-buffer-days.htm (accessed on 28 October 2020).

- Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybė [The Government of Lithuania]. Nutarimas nr. 663 “Dėl lėšų Skyrimo” [Resolution No. 663 Because of Funds Allocation]; Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybė: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2020.

- Oficialiosios Statistikos Portalas [Official Statistics Portal]. Covid-19 Statistika [Covid-19 Statistics]. 2020. Available online: https://osp.stat.gov.lt/covid-19-statistika/itaka-verslui/verslo-tendencijos (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- FM Global. Resilience Index Data. 2020. Available online: https://www.fmglobal.com/research-and-resources/tools-and-resources/resilienceindex/explore-the-data/?&vd=1 (accessed on 16 November 2020).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).