Understanding the Impacts of Chinese Undergraduate Tourism Students’ Professional Identity on Learning Engagement

Abstract

:1. Introduction

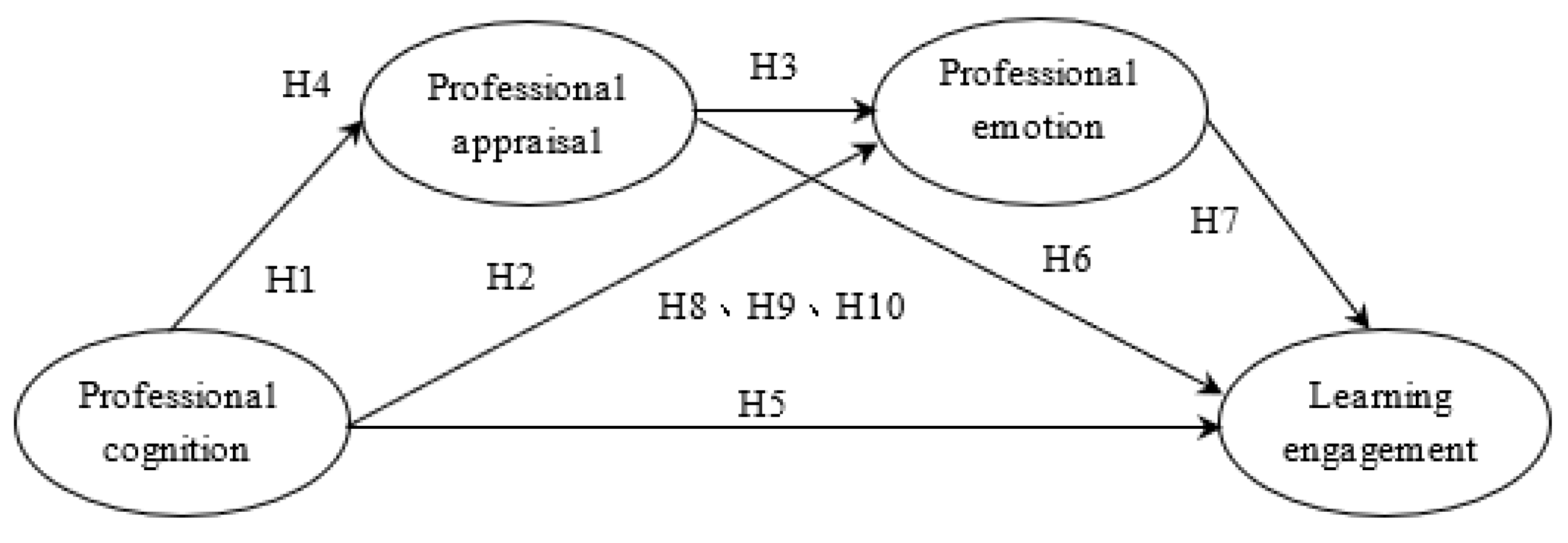

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Social Identity Theory

2.2. Professional Identity (PI)

2.3. Learning Engagement (LE)

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Instrument

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

3.4. Ethical Consideration

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

4.4. Results of the Structural Model

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tsai, C.T.; Hsu, H.; Hsu, Y.C. Tourism and hospitality college students’ career anxiety: Scale development and validation. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2017, 29, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Q.; Liu, C.H. How to establish a creative atmosphere in tourism and hospitality education in the context of China. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2016, 18, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Leung, X.Y.; Huang, S.S.; He, J.M. Factors affecting hotel interns’ satisfaction with internship experience and career intention in China. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2021, 28, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.G.; Zhu, F. On the shrinking of China’s tourism undergraduate education and way out: Thoughts about thirty years of development of tourism higher education. Tour. Trib. 2008, 23, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.H.; Shi, H.; Dong, Y.; Yang, M.; Han, Z. Can engagement in learning enhance tourism undergraduates’ employability? A case study. Int. J. Electr. Eng. Educ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, K.; Ni, R.; Bai, D. Discipline identity in the major of tourism management: Scale development and dimensional measurement. Tour. Trib. 2012, 27, 42–48. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. Professional identity of tourism management program: A perspective from undergraduate students in China. Tour. Hosp. Prospect. 2018, 2, 56–74. [Google Scholar]

- Carmen, M.; Carlos, M.; Yubero, C. Higher education and the sustainable tourism pedagogy: Are tourism students ready to lead change in the post pandemic era? J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2021, 28, 100311. [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan, S.; Macaveiu, C. Understanding aspirations in tourism students. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 39, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. COVID-19 and Tourism 2020: A Year in Review; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2021; pp. 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ina Reichenberger, I.; Marguerite, R. Tourism students’ career strategies in times of disruption. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 48, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, V.A.; Gupta, I. Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospitality and tourism education in India and preparing for the new normal. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2021, 13, 622–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siow, M.L.; Lockstone-Binney, L.; Fraser, B.; Cheung, C.; Shin, J.; Lam, R.; Ramachandran, S.; Novais, M.A.; Bourkel, T.; Baum, T. Re-building students’ post-covid-19 confidence in courses, curriculum and careers for tourism, hospitality, and events. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2021, 33, 270–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Li, Q.; Li, C. How technology facilitates tourism education in covid-19: Case study of Nankai university. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. 2020, 29, 100288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B. Analysis on employment demand of graduates majoring in tourism management in colleges and universities in Hebei province under the background of epidemic situation. Employ. Secur. 2021, 3, 187–188. [Google Scholar]

- CPC Central Committee; State Council. Overall Plan for Deepening the Reform of Educational Evaluation in the New Era. 13 October 2020. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2020-10/13/content_5551032.htm (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Richardson, S. Generation Y’s perceptions and attitudes towards a career in tourism and hospitality. J. Hum. Resour. Hosp. Tour. 2010, 9, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Yang, L.; Shi, Q. Effects of perceptions of the learning environment and approaches to learning on Chinese undergraduates’ learning. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2017, 55, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J.A.; Filsecker, M.; Lawson, M.A. Student engagement, context, and adjustment: Addressing definitional, measurement, and methodological issues. Learn. Instr. 2016, 43, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zepke, N. Student engagement research in higher education: Questioning an academic orthodoxy. Teach. High. Educ. 2014, 19, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzinde, C.N.; Vogt, C.A.; Andereck, K.L.; Pham, L.H.; Ngo, L.T.; Do, H.H. Tourism students’ motivational orientations: The case of Vietnam. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; Gonzalez-roma, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.; Giousmpasoglou, C.; Marinakou, E. Occupational identity and culture: The case of michelin-starred chefs. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 29, 1362–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.P. It’s not only work and pay: The moderation role of teachers’ professional identity on their job satisfaction in rural China. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2019, 15, 971–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, T.; Caricati, L.; Panari, C.; Tonarelli, A. Personal and social aspects of professional identity. An extension of Marcia’s identity status model applied to a sample of university students. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 89, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, R. The Effect of speciality identity on university students’ learning engagement: The mediating role of school belonging. Heilongjiang Res. High. Educ. 2018, 3, 94–99. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Meng, L.; Wang, M.; Feng, X. The effect of professional identity on learning engagement: A multiple mediation model. Psychol. Technol. Appl. 2017, 5, 536–541. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.H.; Xu, J.H.; Zhang, T.C.; Li, Q. Effects of professional identity on turnover intention in China’s hotel employees: The mediating role of employee engagement and job satisfaction. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, H. Social Identity and Inter-Group Relations; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2012, 2, 4–27. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, A.; Vazquez, A. Personal identity and social identity: Two different processes or a single one? Int. J. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 30, 468–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, M.A. Subjective uncertainty reduction through self-categorization: A motivational theory of social identity processes. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 11, 223–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, R. Social Identity; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Smilde, R. Biography, identity, improvisation, sound: Intersections of personal and social identity through improvisation. Arts Humanit. High. Educ. 2016, 15, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dick, R.V.; Wagner, U.; Stellmacher, J.; Christ, O. The utility of a broader conceptualization of organizational identification: Which aspects really matter? J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2004, 77, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trede, F.; Macklin, R.; Bridges, D. Professional identity development: A review of the higher education literature. Stud. High. Educ. 2012, 37, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.P.; Van der Molen, H.T.; Schmidt, H.G. A measure of professional identity development for professional education. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 1504–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.; Doris, U.B. Engagement matters: Student perceptions on the importance of engagement strategies in the online learning environment. Online Learn. 2018, 22, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnard, P.; Dragovic, T.; Ottewell, K.; Lim, W.M. Voicing the professional doctorate and the researching professional’s identity: Theorizing the edd’s uniqueness. Lond. Rev. Educ. 2018, 16, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gross, M.; Hochberg, N. Characteristics of place identity as part of professional identity development among pre-service teachers. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2016, 11, 1243–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Lu, G.S.; Yin, H.B.; Li, L.J. Student engagement for sustainability of Chinese international education: The case of international undergraduate students in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 18, 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, A.L.; Mansell, W.; Morrison, A.P.; Tai, S. Factor structure of the hypomanic attitudes and positive predictions inventory in a student sample. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 50, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Chen, G.; Zhao, X.; Hong, M.; Zhang, X. Construction of cognitive model and empirical analysis of influencing factors of tourism management undergraduate major in local universities. J. Hunan Univ. Sci. Eng. 2021, 42, 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, F.L. On the professional identity of undergraduates majoring in tourism management. J. Yangzhou Coll. Educ. 2020, 38, 70–74. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S. The investigation and analysis of tourism management students’ cognition, emotion and employment intention of professional: Taking Nanyang normal university as an example. J. Nanyang Norm. Univ. 2013, 12, 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Yan, Y. Research on professional cognition, employment intention and professional loyalty of tourism management undergraduates. J. Ningxia Univ. 2012, 34, 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Warr, P.; Inceoglu, I. Job engagement, job satisfaction, and contrasting associations with person-job fit. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Simone, S.; Planta, A.; Cicotto, G. The role of job satisfaction, work engagement, self-efficacy and agentic capacities on nurses’ turnover intention and patient satisfaction. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2017, 39, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, K.Q.; Pekrun, R.; Marsh, H.W.; Loderer, K. Control-value appraisals, achievement emotions, and foreign language performance: A latent interaction analysis. Learn. Instr. 2020, 69, 101356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseman, I.J. Cognitive determinants of emotion: A structural theory. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 5, 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Roseman, I.J.; Spindel, M.S.; Jose, P.E. Appraisals of emotion-eliciting events: Testing a theory of discrete emotions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 899–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, P.C.; Perry, R.P.; Hamm, J.M.; Chipperfield, J.G.; Tze, V. A motivation perspective on achievement appraisals, emotions, and performance in an online learning environment. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 108, 101772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahu, E.R. Framing student engagement in higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 2013, 38, 758–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Eliyahu, A.; Moore, D.; Dorph, R.; Schunn, C.D. Investigating the multidimensionality of engagement: Affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement across science activities and contexts. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 53, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhoc, K.C.; Webster, B.J.; King, R.B.; Li, J.C.; Chung, T.S. Higher education student engagement scale (HESES): Development and psychometric evidence. Res. High. Educ. 2019, 60, 219–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Cui, Y.H.; Zhou, W.Y. Relationships between student engagement and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2018, 46, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, D.J. Structural relationship of key factors for student satisfaction and achievement in asynchronous online learning. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepson, A.; Ryan, W.G. Applying the motivation, opportunity, ability (MOA) model, and self-efficacy (S-E) to better understand student engagement on undergraduate event management programs. Event Manag. 2018, 22, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asikainen, H.; Gijbels, D. Do students develop towards more deep approaches to learning during studies? A systematic review on the development of students’ deep and surface approaches to learning in higher education. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 29, 205–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E.; Marchand, G.; Furrer, C.; Kindermann, T. Engagement and disaffection in the classroom: Part of a larger motivational dynamic? J. Educ. Psychol. 2008, 100, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Laird, T.F.; Seifert, T.A.; Pascarella, E.T.; Mayhew, M.J.; Blaich, C.F. Deeply affecting first-year students’ thinking: Deep approaches to learning and three dimensions of cognitive development. J. High. Educ. 2014, 85, 402–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Zhen, R.; Liu, R.D.; Wang, M.T.; Ding, Y.; Wang, J. The longitudinal linkages among Chinese children’s behavioural, cognitive, and emotional engagement within a mathematics context. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 40, 666–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, J.; Liem, G.; Martin, A.J.; Colmar, S.; Marsh, H.W.; Mcinerney, D. Academic motivation, self-concept, engagement, and performance in high school: Key processes from a longitudinal perspective. J. Adolesc. 2012, 35, 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermunt, J.D.; Vermetten, Y.J. Patterns in student learning: Relationships between learning strategies, conceptions of learning, and learning orientations. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 16, 359–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J.; Kember, D.; Leung, D.Y. The revised two-factor study process questionnaire: R-SPQ-2F. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 71, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Qu, H.L. The mediating role of consumption emotions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 66, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.W.; Jing, J.; Tang, Y. The effect of blended learning platform and engagement on students’ satisfaction: The case from the tourism management teaching. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2020, 27, 100272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanini, C.J.; Rejowski, M.; Ferro, R.C. Tourism and hospitality in Brazil: A model for studies of education competencies. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2020, 29, 100299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, P. The Characteristics and Correlation Study of College Students Specialty Identity. Master’s Thesis, Southwest University, Chongqing, China, May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Huang, A. Revise of the UWES-S of Chinese college samples. Psychol. Res. 2010, 3, 84–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Liu, Y.; Peng, W. Emotion and learning engagement: The mediating role of academic self-efficacy. Chin. J. Spec. Educ. 2020, 4, 89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, H.; Leung, X.; Li, X.; Kwon, J. What influences Chinese students’ intentions to pursue hospitality careers? A comparison of three-year versus four-year hospitality programs. J. Hosp. Leis. Sports Tour. Educ. 2018, 23, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Velicer, W.F.; Fava, J.L. Affects of variable and subject sampling on factor pattern recovery. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 629–686. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, M.S.; Taylor, A.B.; MacKinnon, D.P. Explanation of two anomalous results in statistical mediation analysis. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2012, 47, 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldie, J. The formation of professional identity in medical students: Considerations for educators. Med Teach. 2012, 34, 641–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brien, A.; Thomas, N.J.; Brown, E.A. How hotel employee job-identity impacts the hotel industry: The uncomfortable truth. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2017, 31, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinkler, L.; Smith, V.; Yiannakou, Y.; Robinson, L. Professional identity and the clinical research nurse: A qualitative study exploring issues having an impact on participant recruitment in research. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 74, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabanciogullari, S.; Dogan, S. Relationship between job satisfaction, professional identity and intention to leave the profession among nurses in Turkey. J. Nurs. Manag. 2015, 23, 1076–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Provan David, J.; Dekker Sidney, W.A.; Rae Andrew, J. Benefactor or burden: Exploring the professional identity of safety professionals. J. Saf. Res. 2018, 66, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M. Discussion on the reform of the talent training mode for tourism management major under the guidance of undergraduate qualified evaluation index: Taking Taizhou university as an example. J. Beijing City Univ. 2020, 3, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Curriculum reform and practice analysis of the teaching and education of tourism management majors in colleges and universities. Educ. Teach. Forum 2021, 41, 105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Tavitiyaman, P.; Ren, L.; Fung, C. Hospitality students at the online classes during covid-19: How personality affects experience? J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. 2021, 28, 100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.J.; Davies, J. A teacher’s perspective on student centred learning: Towards the development of best practice in an undergraduate tourism course. J. Hosp. Leis. Sport Tour. Educ. 2014, 14, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, S.; Cheung, C. Academic satisfaction with hospitality and tourism education in Macao: The influence of active learning, academic motivation, and student engagement. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 2018, 38, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matteucci, X.; Aubke, F. Experience care: Efficacy of service-learning in fostering perspective transformation in tourism education. J. Teach. Travel Tour. 2018, 18, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.A.; Thomas, N.J.; Bosselman, R. Are they leaving or staying: A qualitative analysis of turnover issues for generation Y hospitality employees with a hospitality education. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 46, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Demographic Category | Sample Size | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 122 | 22.1 |

| Female | 429 | 77.9 |

| Family source | ||

| Urban area | 197 | 35.8 |

| Small town | 144 | 26.1 |

| Rural area | 210 | 38.1 |

| Grade | ||

| Freshman | 164 | 29.8 |

| Sophomore | 111 | 20.1 |

| Junior | 171 | 31.0 |

| Senior | 105 | 19.1 |

| university Admission | ||

| First choice | 137 | 24.9 |

| Second choice | 65 | 11.8 |

| Third choice | 80 | 14.5 |

| Other choice | 96 | 17.4 |

| Adjusted admission | 173 | 31.4 |

| Items | Factor Loadings | Cronbach’s Alpha | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| Professional cognition (PC) | 0.923 | 3.48 | |

| PC: 1 I know the employment situation of tourism major | 0.784 | ||

| PC 2: I know the position of tourism major in our university | 0.812 | ||

| PC 3: I know the external evaluation of tourism major | 0.854 | ||

| PC 4: On the whole, I have a clear understanding of tourism major | 0.736 | ||

| Professional appraisal (PA) | 0.903 | 3.30 | |

| PA 1: I have a good tourism professional thinking | 0.749 | 3.34 | |

| PA 2: My character matches tourism major | 0.837 | 3.25 | |

| PA 3: Tourism major can reflect my character | 0.831 | 3.16 | |

| PA 4: I feel very relaxed studying tourism | 0.803 | 3.45 | |

| Professional emotion (PE) | 0.864 | 3.71 | |

| PE 1: I am willing to engage in work related to tourism | 0.730 | 3.30 | |

| PE 2; I have accepted the tourism major in my heart | 0.697 | 3.46 | |

| PE 3: I have a positive evaluation of tourism major | 0.810 | 3.70 | |

| PE 4: I have great confidence in the development prospect of a tourism major | 0.823 | 3.68 | |

| PE 5: I have a positive feeling for tourism major | 0.769 | 3.40 | |

| PE 6: I am basically satisfied with the tourism major of our university | 0.735 | 3.32 |

| Construct | CR | AVE | Mean | Discriminant Validity (Correlations and Square Root of AVE) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | PM | PC | LE | ||||

| Professional emotion (PE) | 0.858 | 0.607 | 3.48 | 0.779 | |||

| Professional appraisal (PA) | 0.893 | 0.584 | 3.30 | 0.669 | 0.764 | ||

| Professional cognition (PC) | 0.784 | 0.483 | 3.71 | 0.508 | 0.406 | 0.695 | |

| Learning engagement (LE) | 0.930 | 0.816 | 3.30 | 0.458 | 0.504 | 0.375 | 0.903 |

| Influence Paths | Total Effects | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Standardized Errors | t Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC → LE | 0.471 | 0.203 | 0.268 | 0.067 | 3.022 |

| PC → PE | 0.599 | 0.333 | 0.265 | 0.054 | 6.142 |

| PM → LE | 0.543 | 0.437 | 0.107 | 0.085 | 5.166 |

| PC → PM | 0.396 | 0.396 | — | 0.054 | 7.348 |

| PM → PE | 0.670 | 0.670 | — | 0.070 | 9.523 |

| PE → LE | 0.159 | 0.159 | — | 0.070 | 2.270 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, F.; Chen, Q.; Hou, B. Understanding the Impacts of Chinese Undergraduate Tourism Students’ Professional Identity on Learning Engagement. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13379. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313379

Yu F, Chen Q, Hou B. Understanding the Impacts of Chinese Undergraduate Tourism Students’ Professional Identity on Learning Engagement. Sustainability. 2021; 13(23):13379. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313379

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Fenglong, Qian Chen, and Bing Hou. 2021. "Understanding the Impacts of Chinese Undergraduate Tourism Students’ Professional Identity on Learning Engagement" Sustainability 13, no. 23: 13379. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313379

APA StyleYu, F., Chen, Q., & Hou, B. (2021). Understanding the Impacts of Chinese Undergraduate Tourism Students’ Professional Identity on Learning Engagement. Sustainability, 13(23), 13379. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313379