The Effects of Leisure Life Satisfaction on Subjective Wellbeing under the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Role of Stress Relief

Abstract

:1. Introduction

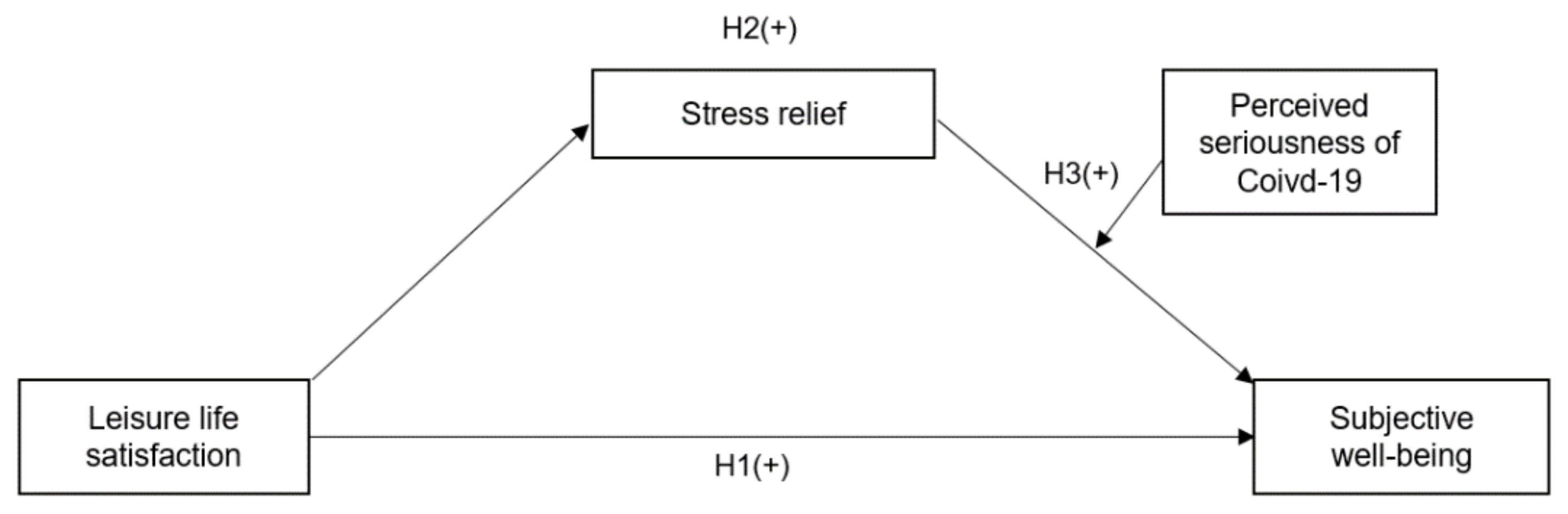

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Leisure Life Satisfaction and Subjective Wellbeing

2.2. Stress Relief as a Mediating Mechanism

2.3. COVID-19 as a Contextual Moderator Affecting the Relationship between Stress Relief and Subjective Wellbeing

3. Method

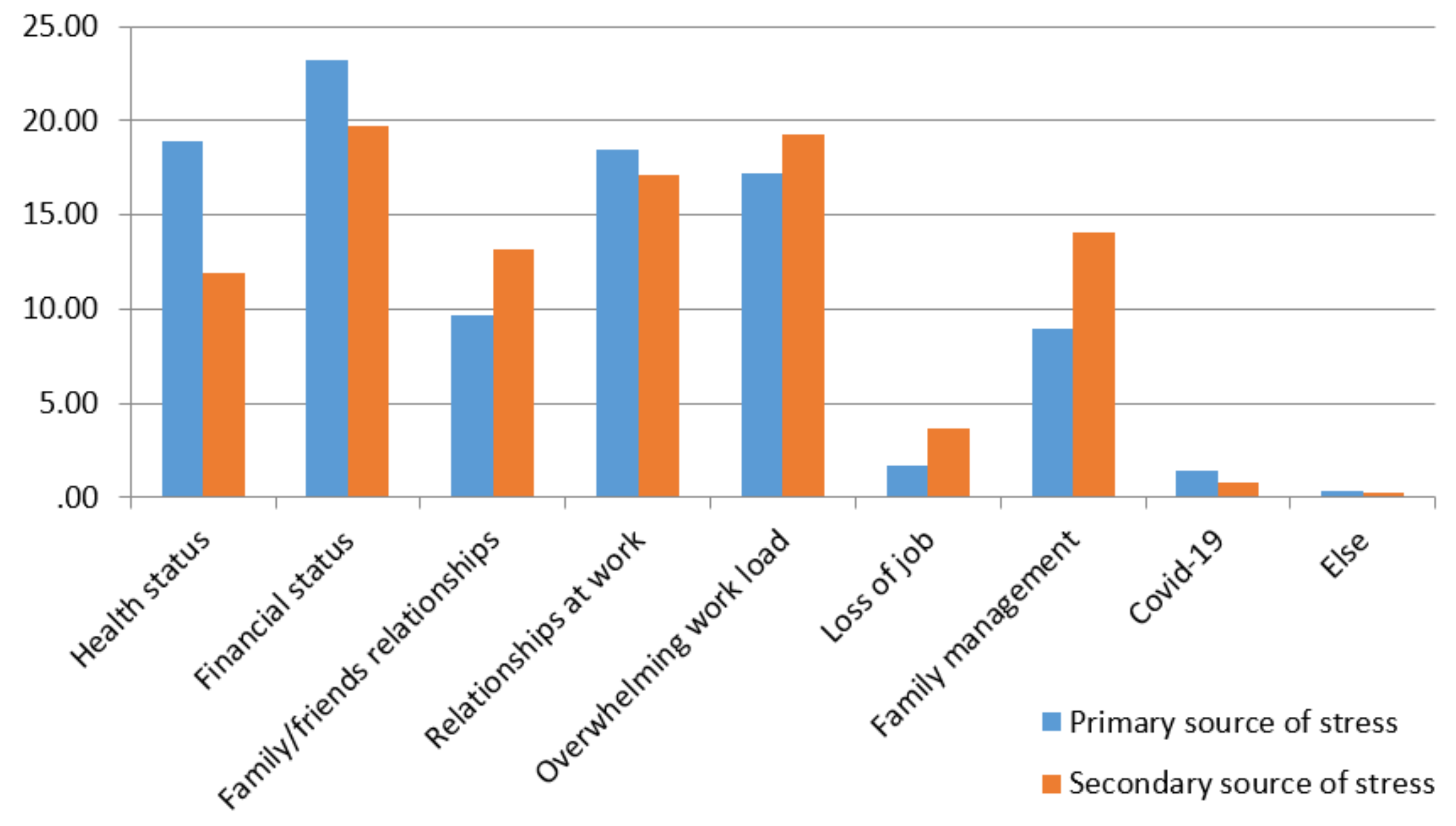

3.1. Sample

3.2. Constructs and Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analyses

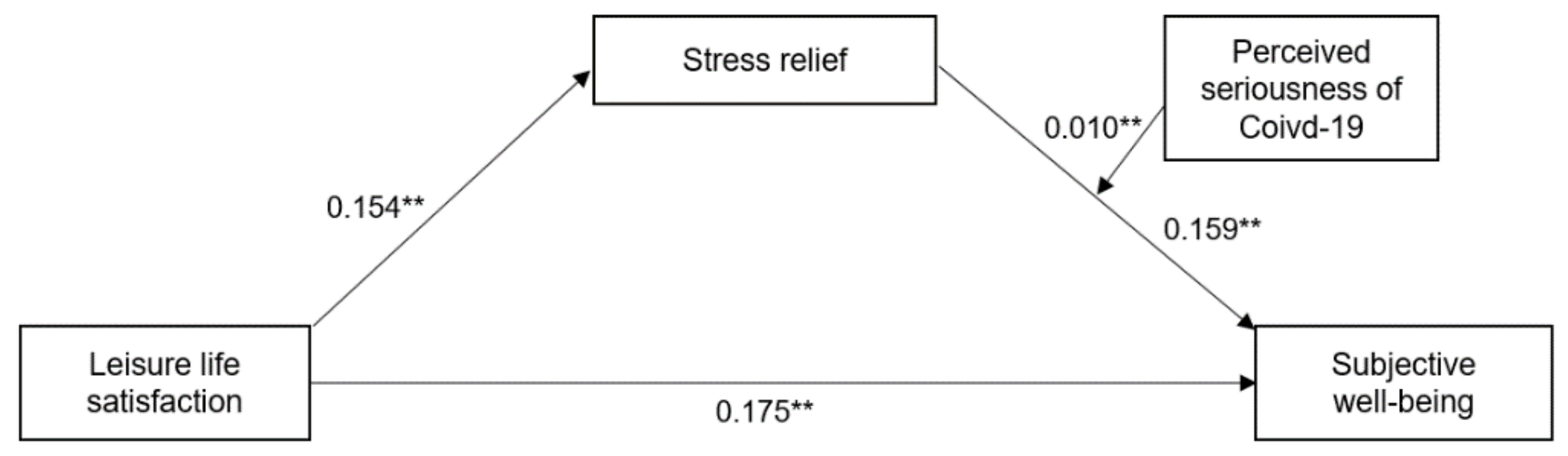

4.2. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion and Implication

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHOQOL Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol. Med. 1998, 28, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHOQOL Group. Development of the WHOQOL: Rationale and current status. Int. J. Ment. Health 1994, 23, 24–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHOQOL Group. A cross-cultural study of spirituality, religion, and personal beliefs as components of quality of life. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 1486–1497. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. Subjective well-being. In The Science of Well-Being; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 11–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, P.M. Predicting employee life satisfaction: A coherent model of personality, work, and nonwork experiences, and domain satisfactions. J. Appl. Psychol. 1999, 84, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M. Life satisfaction and satisfaction in domains of life: Is it a simple relationship? J. Happiness Stud. 2006, 7, 467–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, J.D.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. Developing a macro measure of QOL/leisure satisfaction with travel/tourism services: Stage one (conceptualization). In Developments in Quality-of-Life Studies in Marketing. Proceedings of the Fifth Quality of Life/Marketing Conference, Williamsburg, VA, USA, 30 November–2 December 1995; Williamsburg, V.A., Meadow, H.L., Sirgy, M.J., Rahtz, D.R., Eds.; Academy of Marketing Science: DeKalb, IL, USA, 1995; Volume 5, pp. 145–149. [Google Scholar]

- Barling, J.; Kelloway, E.K.; Frone, M.R. Handbook of Work Stress; Sage Publications: Southend Oaks, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N.; Gordon, J.R. Addressing the stress of work and elder caregiving of the graying workforce: The moderating effects of financial strain on the relationship between work-caregiving conflict and psychological well-being. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 53, 723–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boss, P.; Bryant, C.M.; Mancini, J.A. Family Stress Management: A Contextual Approach; Sage Publications: Southend Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Parr, M.G.; Lashua, B.D. What is leisure? The perceptions of recreation practitioners and others. Leis. Sci. 2004, 26, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyle, M. Leisure. In The Psychology of Happiness; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, D.M.; Charles, S.T.; Mogle, J.; Drewelies, J.; Aldwin, C.M.; Spiro, A., III; Gerstorf, D. Charting adult development through (historically changing) daily stress processes. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yu, B. Serious leisure, leisure satisfaction and subjective well-being of Chinese university students. Soc. Indic. Res. 2015, 122, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.B.; Leibbrandt, S.; Moon, H. A critical review of the literature on social and leisure activity and wellbeing in later life. Ageing Soc. 2011, 31, 683–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ito, E.; Walker, G.J.; Liu, H.; Mitas, O. A cross-cultural/national study of Canadian, Chinese, and Japanese university students’ leisure satisfaction and subjective well-being. Leis. Sci. 2017, 39, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, L.; Daykin, N.; Kay, T. Leisure and wellbeing. Leis. Stud. 2020, 39, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sirgy, M.J. Leisure Wellbeing. In The Psychology of Quality of Life; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 505–523. [Google Scholar]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Uysal, M.; Kruger, S. Towards a benefits theory of leisure well-being. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2017, 12, 205–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1990; Volume 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hills, P.; Argyle, M.; Reeves, R. Individual differences in leisure satisfactions: An investigation of four theories of leisure motivation. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2000, 28, 763–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A.; Látková, P.; Sun, Y.-Y. The relationship between leisure and life satisfaction: Application of activity and need theory. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 86, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.B.; Tay, L.; Diener, E. Leisure and subjective well-being: A model of psychological mechanisms as mediating factors. J. Happiness Stud. 2014, 15, 555–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. Stress in America™ 2021: Stress and Decision-Making during the Pandemic; America Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kujanpää, M.; Syrek, C.; Lehr, D.; Kinnunen, U.; Reins, J.A.; de Bloom, J. Need satisfaction and optimal functioning at leisure and work: A longitudinal validation study of the DRAMMA model. J. Happiness Stud. 2021, 22, 681–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007, 14, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jackson, E.L.; Crawford, D.W.; Godbey, G. Negotiation of leisure constraints. Leis. Sci. 1993, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, D.W.; Jackson, E.L.; Godbey, G. A hierarchical model of leisure constraints. Leis. Sci. 1991, 13, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godbey, G.; Crawford, D.W.; Shen, X.S. Assessing hierarchical leisure constraints theory after two decades. J. Leis. Res. 2010, 42, 111–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuykendall, L.; Tay, L.; Ng, V. Leisure engagement and subjective well-being: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neulinger, J. Leisure lack and the quality of life: The broadening scope of the leisure professional. Leis. Stud. 1982, 1, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyle, M. The Psychology of Happiness; Methuen & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, K.; You, S. Leisure type, leisure satisfaction and adolescents’ psychological wellbeing. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 2013, 7, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barrios-Choplin, B.; McCraty, R.; Cryer, B. An inner quality approach to reducing stress and improving physical and emotional wellbeing at work. Stress Med. 1997, 13, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, V.; Penman, D. Mindfulness for Health: A Practical Guide to Relieving Pain, Reducing Stress and Restoring Wellbeing; Hachette UK: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hull, R.B., IV. Mood as a product of leisure: Causes and consequences. J. Leis. Res. 1990, 22, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Oerlemans, W.; Sonnentag, S. Workaholism and daily recovery: A day reconstruction study of leisure activities. J. Organ. Behav. 2013, 34, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C. Taking Leisure Seriously: An Investigation of Leisure to Work Enrichment. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnentag, S. Psychological detachment from work during leisure time: The benefits of mentally disengaging from work. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2012, 21, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnewies, C.; Sonnentag, S.; Mojza, E.J. Recovery during the weekend and fluctuations in weekly job performance: A week-level study examining intra-individual relationships. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 419–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ten Brummelhuis, L.L.; Bakker, A.B. Staying engaged during the week: The effect of off-job activities on next day work engagement. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Heid, A.R.; Cartwright, F.; Wilson-Genderson, M.; Pruchno, R. Challenges experienced by older people during the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Gerontologist 2021, 61, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanberg, C.R.; Csillag, B.; Douglass, R.P.; Zhou, L.; Pollard, M.S. Socioeconomic status and well-being during COVID-19: A resource-based examination. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 1382–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Floyd, C.; Kim, A.C.; Baker, B.J.; Sato, M.; James, J.D.; Funk, D.C. To be or not to be: Negotiating leisure constraints with technology and data analytics amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Leis. Stud. 2020, 40, 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers-Jarrell, T.; Vervaecke, D.; Meisner, B.A. Intergenerational family leisure in the COVID-19 pandemic: Some potentials, pitfalls, and paradoxes. World Leis. J. 2021, 63, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Da, S. The relationships between leisure and happiness-A graphic elicitation method. Leis. Stud. 2020, 39, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslau, J.; Finucane, M.L.; Locker, A.R.; Baird, M.D.; Roth, E.A.; Collins, R.L. A longitudinal study of psychological distress in the United States before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Prev. Med. 2021, 143, 106362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.B.; Sirgy, M.J.; Bosnjak, M.; Lee, D.-J. A Preregistered study of the effect of shopping satisfaction during leisure travel on satisfaction with life overall: The mitigating role of financial concerns. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 639–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, A.-L.; Leppänen, A.; Jahkola, A. Validity of a single-item measure of stress symptoms. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2003, 29, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Geirdal, A.Ø.; Ruffolo, M.; Leung, J.; Thygesen, H.; Price, D.; Bonsaksen, T.; Schoultz, M. Mental health, quality of life, wellbeing, loneliness and use of social media in a time of social distancing during the COVID-19 outbreak. A cross-country comparative study. J. Ment. Health 2021, 30, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korea Central Disaster Management Headquarters. Overview of Social Distancing System. Available online: http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/en/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Park, K.-H.; Kim, A.-R.; Yang, M.-A.; Lim, S.-J.; Park, J.-H. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the lifestyle, mental health, and quality of life of adults in South Korea. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247970. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, C.M.; Strauss, K.; Arnold, J.; Stride, C. The relationship between leisure activities and psychological resources that support a sustainable career: The role of leisure seriousness and work-leisure similarity. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020, 117, 103340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woon, L.S.-C.; Sidi, H.; Jaafar, N.N.; Bin Abdullah, M.L. Mental health status of university healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A post–movement lockdown assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, T. Stress; The Macmillan Press LTD: London, UK; Basingstoke, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, J.T.S. Stress, health and leisure satisfaction: The case of teachers. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 1996, 10, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar Moni, A.S.; Abdullah, S.; Bin Abdullah, M.F.I.L.; Kabir, M.S.; Alif, S.M.; Sultana, F.; Salehin, M.; Islam, S.M.S.; Cross, W.; Rahman, M.A. Psychological distress, fear and coping among Malaysians during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257304. [Google Scholar]

- Van Boven, L.; Ashworth, L. Looking forward, looking back: Anticipation is more evocative than retrospection. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2007, 136, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Age | Marital Status | Employment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10s | 5.0 % | Married (living together) | 68.5% | Administrative | 5.2% |

| 20s | 16.2% | Married (living apart) | 0.4% | Professionals | 8.3% |

| 30s | 17.7% | Single | 23.4% | Office workers | 27.9% |

| 40s | 18.0% | Divorced | 2.8% | Service providers | 10.9% |

| 50s | 18.0% | Widowed | 4.9% | Sales representatives | 8.1% |

| 60s or more | 25.1% | Students | 7.6% | ||

| Gender | Education | Housewives | 17.3% | ||

| Female | 48.0 % | Elementary school | 2.4 | Not employed | 6.5% |

| Male | 52.0 % | Middle school | 4.5 | Etc. | 8% |

| High school | 25.2 | ||||

| College | 13.5 | ||||

| University | 47.5 | ||||

| Graduate school | 6.8 | ||||

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leisure life satisfaction | 3.14 | 0.79 | - | |||

| Stress relief | 2.69 | 0.91 | 0.115 ** | - | ||

| Subjective wellbeing | 3.31 | 0.74 | 0.222 ** | 0.268 ** | - | |

| Perceived seriousness of COVID-19 | 4.16 | 0.87 | −0.040 ** | −0.120 ** | 0.012 * | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, G.B.; Kim, N. The Effects of Leisure Life Satisfaction on Subjective Wellbeing under the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Role of Stress Relief. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13225. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313225

Yu GB, Kim N. The Effects of Leisure Life Satisfaction on Subjective Wellbeing under the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Role of Stress Relief. Sustainability. 2021; 13(23):13225. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313225

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Grace B., and Najung Kim. 2021. "The Effects of Leisure Life Satisfaction on Subjective Wellbeing under the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Role of Stress Relief" Sustainability 13, no. 23: 13225. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313225

APA StyleYu, G. B., & Kim, N. (2021). The Effects of Leisure Life Satisfaction on Subjective Wellbeing under the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Role of Stress Relief. Sustainability, 13(23), 13225. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313225