Motivations and Barriers for the Sustainable Internationalization of the Portuguese Textile Sector

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Motivations for Internationalization

2.2. The Barriers to Internationalization

3. Methodology

3.1. Characterization of the Textile Sector in Portugal

3.2. Type of Study and Case Selection

- Identification of companies in the textile sector that are heavily dependent on exports;

- Selection of companies for convenience: ease of access to information;

- Companies with different characteristics: despite these companies being in the same sector of activity, it was decided to select companies with different characteristics, such as size, countries they had expanded into, market segments, etc.

3.3. Data Collection and Processing

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Internationalization Process

4.1.1. Motivations for Internationalization

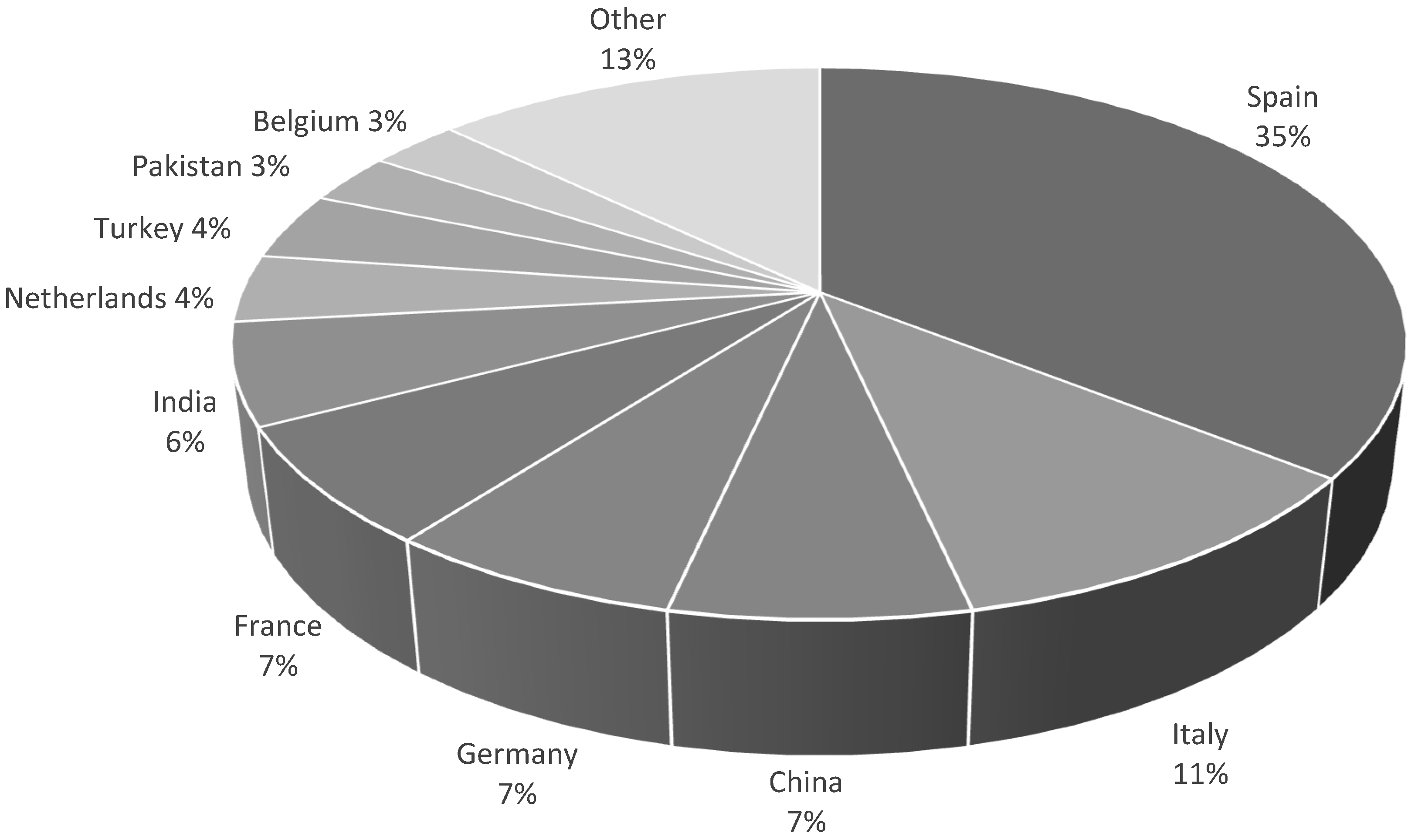

4.1.2. Criteria for Choosing a Country

4.1.3. Advantages of Internationalization

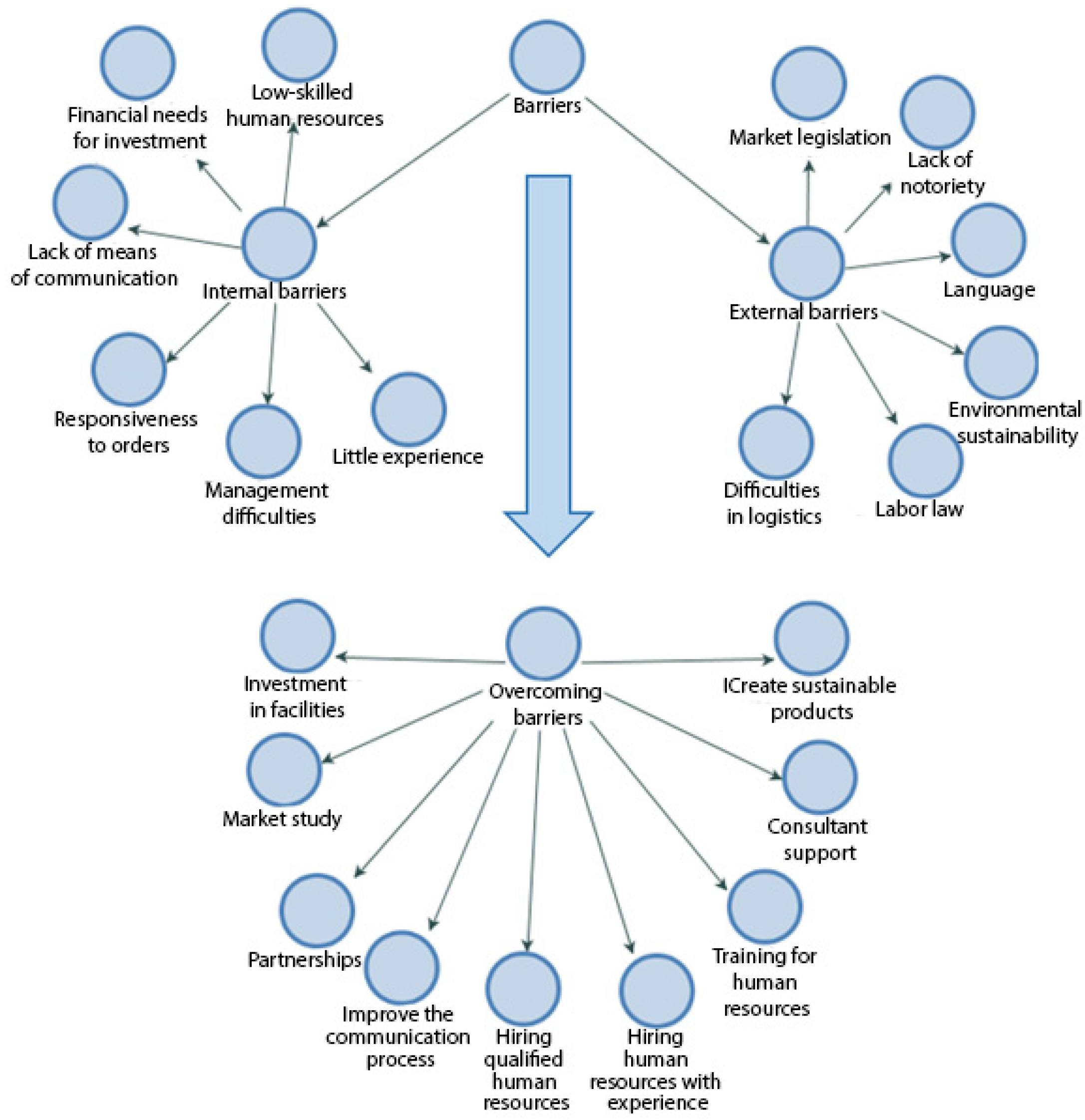

4.2. Barriers to Internationalization

4.2.1. Internal and External Barriers

4.2.2. Overcoming Barriers

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kotabe, M.M.; Helsen, K. Global Marketing Management; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mühlbacher, H.; Leihs, H.; Dahringer, L. International Marketing: A Global Perspective, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Arndt, C.; Buch, C.M.; Mattes, A. Disentangling barriers to internationalization. Can. J. Econ./Rev. Can. D’économique 2012, 45, 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahen, F.R.; Lahiri, S.; Borini, F.M. Managerial perceptions of barriers to internationalization: An examination of Brazil’s new technology-based firms. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1973–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, V. Estratégias de Internacionalização das Empresas Portuguesas. Comércio e Investimento Internacional ICEP. Portugal. Investimentos; Comércio e Turismo de Portugal (edição): Covilhã, Portugal, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, J.; Darder, F. Direccion de Empresas Internacionales; Pearson: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, R. The Internationalization Process of the Firm Revisited: Explaining Patterns of Geographic Sales Expansion; Management Report; Erasmus University Roterdam: Roterdão, The Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Onkvisit, S.; Shaw, J.J. Process of International Marketing. International Marketing: Analysis and Strategy, 4th ed.; Routledge: Estados Unidos, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Leonidou, L.C. Barriers to export management: An organizational and internationalization analysis. J. Int. Manag. 2000, 6, 121–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miesenbock, K.J. Small Businesses and Exporting: A Literature Review. Int. Small Bus. J. 1988, 6, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erraach, Y.; Jaafer, F.; Radić, I.; Donner, M. Sustainability Labels on Olive Oil: A Review on Consumer Attitudes and Behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Sekhar, C.; Vyas, V. Barriers to internationalization: A study of small and medium enterprises in India. J. Int. Entrep. 2016, 14, 513–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niñerola, A.; Sánchez-Rebull, M.-V.; Hernandez-Lara, A.-B. Entry modes and barriers to internationalisation in China: An overview of management consulting firms. Meas. Bus. Excel. 2017, 21, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilkey, W.J. An Attempted Integration of the Literature on the Export Behavior of Firms. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1978, 9, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okpara, J.O.; Kabongo, J.D. Export barriers and internationalisation: Evidence from SMEs in an emergent African economy. Int. J. Bus. Glob. 2010, 5, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A.; Paul, J.; Chavan, M. Internationalization barriers of SMEs from developing countries: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 26, 1281–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C. An Analysis of the Barriers Hindering Small Business Export Development. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2004, 42, 279–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsikeas, C.S.; Morgan, R.E. Differences in Perceptions of Exporting Problems Based on Firm Size and Export Market Experience. Eur. J. Mark. 1994, 28, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Akter, M.; Odunukan, K.; Haque, S.E. Examining economic and technology-related barriers of small-and medium-sized enterprises internationalisation: An emerging economy context. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2020, 3, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, F.; Franco, M. The role of cooperative alliances in internationalization strategy: Qualitative study of Portuguese SMEs in the textile sector. J. Strategy Manag. 2018, 11, 461–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, V.; Gonçalves, A.C.; Braga, A. The Portuguese textile industry business co-operation: Informal relationships for international entry. Rom. Rev. Precis. Mech. Opt. Mechatron. 2016, 49, B52. [Google Scholar]

- Rua, O.; França, A.; Ortiz, R.F. Key drivers of SMEs export performance: The mediating effect of competitive advantage. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank of Portugal. Nota de Informação Estatística: Análise Setorial da Indústria dos Têxteis e Vestuário 2012–2016 (Statistical Information Note: Sectoral Analysis of the Textile and Clothing Industry; Bank of Portugal: Lisbon, Portugal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, S.; Diz, H. Estratégias de Internacionalização; Publisher Team: Lisboa, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, A. Estratégia: Sucesso em Portugal; Editorial Verbo: Lisboa, Portugal, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lorga, S. Internacionalização e Redes de Empresas: Conceitos e Teorias; Editorial Verbo: Lisboa, Portugal, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hollensen, S. Essential of Global Marketing; Pearson Education Limited: Harlow, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Tatoglu, E.; Demirbag, M.; Kaplan, G. Motives for Retailer Internationalization to Central and Eastern Europe. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade 2003, 39, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsikeas, C.S.; Deng, S.L.; Wortzel, L.H. Perceived Export Success Factors of Small and Medium-Sized Canadian Firms. J. Int. Mark. 1997, 5, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J. The internationalization of small computer software firms: A further challenge to stages theory. Eur. J. Mark. 1995, 29, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tybejee, T.T. Internationalization of high tech firms: Initial vs. extended involvement. J. Glob. Mark. 1994, 7, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D.A. Export stimulation of micro- and small locally owned firms from emerging environments: New evidence. J. Int. Entrep. 2008, 6, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavusgil, S.T. Differences among Exporting Firms Based on Their Degree of Internationalisation. J. Bus. Res. 1984, 12, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C. Factors Stimulating Export Business: An Empirical Investigation. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2011, 14, 43–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesar, G.; Tarleton, J.S. Comparison of Wisconsin and Virginia small and medium-sized exporters: Aggressive and passive exporters. Export. Manag. Int. Context 1982, 2, 85–112. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, B.R.; Chakrabarti, R.; Palihawadana, D. Investigating the export marketing activity of SMEs operating in international healthcare markets. J. Med. Mark. 2006, 6, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karafakioglu, M. Export Activities of Turkish Manufacturers. Int. Mark. Rev. 1986, 3, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabino, S. An examination of barriers to exporting encountered by small manufacturing firm. Manag. Int. Rev. 1980, 20, 67–73. [Google Scholar]

- Rundh, B. International marketing behaviour amongst exporting firms. Eur. J. Mark. 2007, 41, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fillis, D. The internationalisation process of the craft micro-enterprise. J. Dev. Entrep. 2002, 7, 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Child, J.; Rodrigues, S.B. The internationalization of Chinese firms: A case for theoretical extension? Manag. Organ. Rev. 2005, 1, 381–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Singh, D.A.; Gaur, A.S.; Schmid, F.P. Corporate diversification, TMT experience, and performance. Manag. Int. Rev. 2010, 50, 35–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, J.; Vahlne, J.-E. The Uppsala Internationalization Process Model Revisited: From Liability of Foreignness to Liability of Outsidership. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2009, 40, 1411–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais, F.; Ferreira, J. SME internationalisation process: Key issues and contributions, existing gaps and the future research agenda. Eur. Manag. J. 2020, 38, 62–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Rocha, A.; Kury, B.; Monteiro, J. The diffusion of exporting in Brazilian industrial clusters. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2009, 21, 529–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, J.C.; Martins, L. Exporting barriers: Insights from Portuguese small- and medium-sized exporters and non-exporters. J. Int. Entrep. 2010, 8, 254–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuada, J. Internationalisation of firms in developing countries: Towards an integrated conceptual framework. Int. Bus. Econ. 2006, 43, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Craveiro, R.P.C. Motivações e Barreiras à Internacionalização. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Beira Interior, Covilhã, Portugal, 18 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Arteaga-Ortiz, J.; Fernández-Ortiz, R. Why Don’t We Use the Same Export Barrier Measurement Scale? An Empirical Analysis in Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2010, 48, 395–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahiya, E.T. Export barriers and path to internationalization: A comparison of conventional enterprises and international new ventures. J. Int. Entrep. 2013, 11, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uner, M.M.; Kocak, A.; Cavusgil, E.; Cavusgil, S.T. Do barriers to export vary for born globals and across stages of internationalization? An empirical inquiry in the emerging market of Turkey. Int. Bus. Rev. 2013, 22, 800–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Parthasarathy, S.; Gupta, P. Exporting challenges of SMEs: A review and future research agenda. J. World Bus. 2017, 52, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutashobya, L.; Jaensson, J. Small firms’ internationalization for development in Tanzania. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2004, 31, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The Enlarging European Union at the United Nations: Making Multilateralism Matter; Commission of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook: 2005; OECD: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, S.; Reid, I. Constraints facing small western firms in transitional markets. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2006, 18, 187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, D. International entrepreneurship and the small business. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2004, 16, 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Ortega, S. Export barriers: Insights from small and medium-sized firms. Int. Small Bus. J. 2003, 21, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G.R. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Drees, J.M.; Heugens, P.P. Synthesizing and extending resource dependence theory: A meta-analysis. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 1666–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pfeffer, J. A resource dependence perspective on intercorporate relations. Intercorporate Relat. Struct. Anal. Bus. 1988, 1, 25–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.J.; Withers, M.C.; Collins, B.J. Resource Dependence Theory: A Review. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 1404–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haahti, A.; Madupu, V.; Yavas, U.; Babakus, E. Cooperative strategy, knowledge intensity and export performance of small and medium sized enterprises. J. World Bus. 2005, 40, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessels, J.; Parker, S.C. Constraints, internationalization and growth: A cross-country analysis of European SMEs. J. World Bus. 2013, 48, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APT. Annual Report Directory 2019. 2019. Available online: //atp.pt/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/ATP-Diretorio-2019-1.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Vaz, P.; Agiz, D. ROADMAP Para a Especialização Inteligente e Competitividade Global da ITV Portuguesa. 2017. Available online: https://atp.pt/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/RoadMap.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, London, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Altinay, M.; Hussain, K. Sustainable tourism development: A case study of North Cyprus. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2005, 17, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perren, L.; Ram, M. Case-study method in small business and entrepreneurial research—Mapping boundaries and perspectives. Int. Small Bus. J. 2004, 22, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lune, H.; Berg, B.L. Qualitative research methods for the social sciences; Pearson: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rowley, J. Using case studies in research. Manag. Res. News 2002, 25, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuli, F. The Basis of Distinction Between Qualitative and Quantitative Research in Social Science: Reflection on Ontological, Epistemological and Methodological Perspectives. Ethiop. J. Educ. Sci. 2011, 6, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benbasat, I.; Goldstein, D.K.; Mead, M. The Case Research Strategy in Studies of Information Systems. MIS Q. 1987, 11, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, F. Portugal 1997—A internacionalização em dez tópicos. Econ. Prospect. 1997, 1, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Solberg, C.A.; Durrieu, F. Strategy development in international markets: A two tier approach. Int. Mark. Rev. 2008, 25, 520–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czinkota, M.R. International Business, 5th ed.; The Dryden Press: Orlando, FL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, P.C. Historic and Emergent Trends in Chinese Outward Direct Investment. Manag. Int. Rev. 2008, 48, 715–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, L.S.; Luostarinen, R. Internationalization: Evolution of a Concept. J. Gen. Manag. 1988, 14, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahlne, J.E.; Wiedersheim-Paul, F. Psychic Distance: An Inhibiting Factor in International Trade; Centre for International Business Working Paper Series; University of Uppsala: Uppsala, Sweden, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Onkelinx, J.; Sleuwaegen, L. Internationalization of SMEs; Flanders DC: Leuven, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Etemad, H. Internationalization of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises: A Grounded Theoretical Framework and an Overview. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2009, 21, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, D.; Sapienza, H.J.; Crijns, H. The Internationalization of Small and Medium-Sized Firms. Small Bus. Econ. 2005, 24, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, V.; Darroch, J. Barriers to internationalization: A study of entrepreneurial new ventures in New Zealand. J. Int. Entrep. 2004, 2, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acs, Z.J.; Morck, R.; Shaver, J.M.; Yeung, B. The Internationalization of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises: A Policy Perspective. Small Bus. Econ. 1997, 9, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviatt, B.M.; McDougall, P.P. Defining International Entrepreneurship and Modeling the Speed of Internationalization. Entrep. Theory Pr. 2005, 29, 537–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, L.C. Empirical Research on Export Barriers: Review, Assessment, and Synthesis. J. Int. Mark. 1995, 3, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, H.T.T.; Igwe, P.A. Internationalization of Firms and Entrepreneur’s Motivations: A Review and Research Agenda. In Societal Entrepreneurship and Competitiveness; Dana, L.-P., Ratten, V., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2019; pp. 29–46. [Google Scholar]

| Textile Sector in Portugal | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production (million €) | 6485 | 6767 | 7147 | 7439 | 7500 |

| Turnover (million €) | 6712 | 6942 | 7362 | 7607 | 7610 |

| Exports (million €) | 4620 | 4811 | 5036 | 5215 | 5314 |

| Imports (million €) | 3608 | 3835 | 3940 | 4139 | 4307 |

| Job | 128,414 | 131,513 | 135,521 | 136,928 | 138,000 |

| Company | Location | Year of Start of Activity | No. of Collaborators | Sector | % Export | Main Export Markets |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Quinchães | 1996 | 90 | Serial outerwear manufacturing | 100% | Spain Italy United Kingdom |

| 2 | Quinchães | 2016 | 17 | Serial outerwear manufacturing | 100% | Spain Turkey Morocco |

| 3 | Medelo | 1993 | 34 | Manufacture of underwear, other articles and clothing accessories | 90% | Spain |

| 4 | Vila Nova de Famalicão | 1937 | 190 | Finishing fabrics and knits | 100% | Spain United Kingdom France Finland Germany |

| 5 | Paços | 2013 | 3 | Clothing, footwear and leather industry | 90% | Germany |

| 6 | Quinchães | 2000 | 79 | Serial outerwear manufacturing | 100% | Spain England |

| 1st part |

|

| 2nd part |

|

| 3rd part |

|

| Company | Interviewee | Gender | Age | Academic Education | Office | Years in the Company |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company 1 | Interviewee 1 | Male | 33 | High school | Logistics | 7 years |

| Company 2 | Interviewee 2 | Female | 44 | Graduation | General Director | 4 years |

| Company 3 | Interviewee 3 | Female | 26 | Graduation | Commercial | 3 years |

| Company 4 | Interviewee 4 | Male | 50 | Graduation | Responsible for R&D | 20 years |

| Company 5 | Interviewee 5 | Female | 44 | Graduation | Customer Manager | 7 years |

| Company 6 | Interviewee 6 | Male | 43 | High school | Manager | 20 years |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galvão, A.R.; Marques, C.S.; Mascarenhas, C.; Braga, V.; Pereira, R. Motivations and Barriers for the Sustainable Internationalization of the Portuguese Textile Sector. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313147

Galvão AR, Marques CS, Mascarenhas C, Braga V, Pereira R. Motivations and Barriers for the Sustainable Internationalization of the Portuguese Textile Sector. Sustainability. 2021; 13(23):13147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313147

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalvão, Anderson Rei, Carla Susana Marques, Carla Mascarenhas, Vitor Braga, and Rita Pereira. 2021. "Motivations and Barriers for the Sustainable Internationalization of the Portuguese Textile Sector" Sustainability 13, no. 23: 13147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313147

APA StyleGalvão, A. R., Marques, C. S., Mascarenhas, C., Braga, V., & Pereira, R. (2021). Motivations and Barriers for the Sustainable Internationalization of the Portuguese Textile Sector. Sustainability, 13(23), 13147. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313147