1. Introduction

Brideprice/dowry is increasingly attracting the attention of scholars and policymakers because of its pervasive prevalence in developing countries and the significant property transfers and bargaining it entails [

1,

2]. They can be several times larger than the annual income of rural households, which can be substantial enough to affect the welfare of women and a society’s distribution of wealth [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Thus, China’s No. 1 Central Document in recent years explicitly states that excessive brideprice has an adverse effect on a healthy social environment due to its huge economic burden imposed on rural households. The high brideprice makes the phenomenon of “poverty due to marriage” occur in rural China frequently, which is also one of the most important reasons for the decline of the marriage rate in China. This poses great challenges to the sustainable development of Chinese society and the rational change of population structure.

According to Becker’s marriage market theory framework [

9,

10,

11], the means of matching could be one of the determinants of marriage payments. There are two ways of matching couples: love match and arranged marriages. Love match means a couple become married because of romantic love; however, arranged marriage means they become married due to parents choosing their marital partners [

12]. In ancient China, most people got married based on parents’ order or matchmaker’s word (

Fumu Zhiming,

Meishuo Zhiyan). The couple did not even meet or knew little about each other before becoming married. Love match at that time was even not a moral or well-bred behavior. Love match and arranged marriage have a new meaning and performance in contemporary China. With the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, the proportion of love match gradually increased, especially after the Reform and Opening up and the implementation of the Marriage Law. However, there are still a considerable number of couples becoming married based on parents’ consideration of potential marriage partners’ economic situation or the pressure of social customs.

The relationship between match types of couples and marriage payments in other countries has been paid high attention. The co-existence of arranged marriage and dowry in South Asia has been well noted by many scholars [

3,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Singh (1997) used data from 10 villages in India and found that the financial burden of arranging the daughters’ marriage on their parents has increased [

17]. Some studies found that cash transfer at the time of marriage can potentially serve as a screening instrument to distinguish grooms of different qualities because some characteristics related to the quality of the groom are unobservable in ‘arranged’ marriage, such as personality and ability [

12]. Diamond-Smith et al. (2020) conducted in-depth qualitative interviews in Nepal and found that husbands with semi-arranged (couples often talk or meet before marriage) have growing ambivalence about dowry [

18].

Studies focusing on this issue in China are rare. To the best of our knowledge, there are only two empirical studies touching up on this topic in China. Wang studied the internal correlation between matching types and brideprice paid by the grooms’ family using case studies in rural areas of Sichuan and Henan provinces [

19]. The survey shows that the love-match marriage model dominated by the children correlates with the low costs of brideprice, vice versa. The ontological value of intergenerational responsibility lays behind the two different marriage models in rural area. The other research found that the increasing popularity of love match plays a role in solving the marriage squeeze based on the case study method in a village in Shaanxi province [

20].

There are some potential gaps to be narrowed in previous studies. Firstly, few studies in China have empirically tested the relationship between love match and marriage payment. Secondly, most previous studies ignore the substitution effect of wedding house investment and wedding reception expenditure on brideprice or dowry, which is not in line with reality. Thirdly, the relationship of love match on marriage payment may vary with the marriage distance, which measures the distance between the couple’s birthplaces. There are few studies focusing on the role of marriage distance in this relationship.

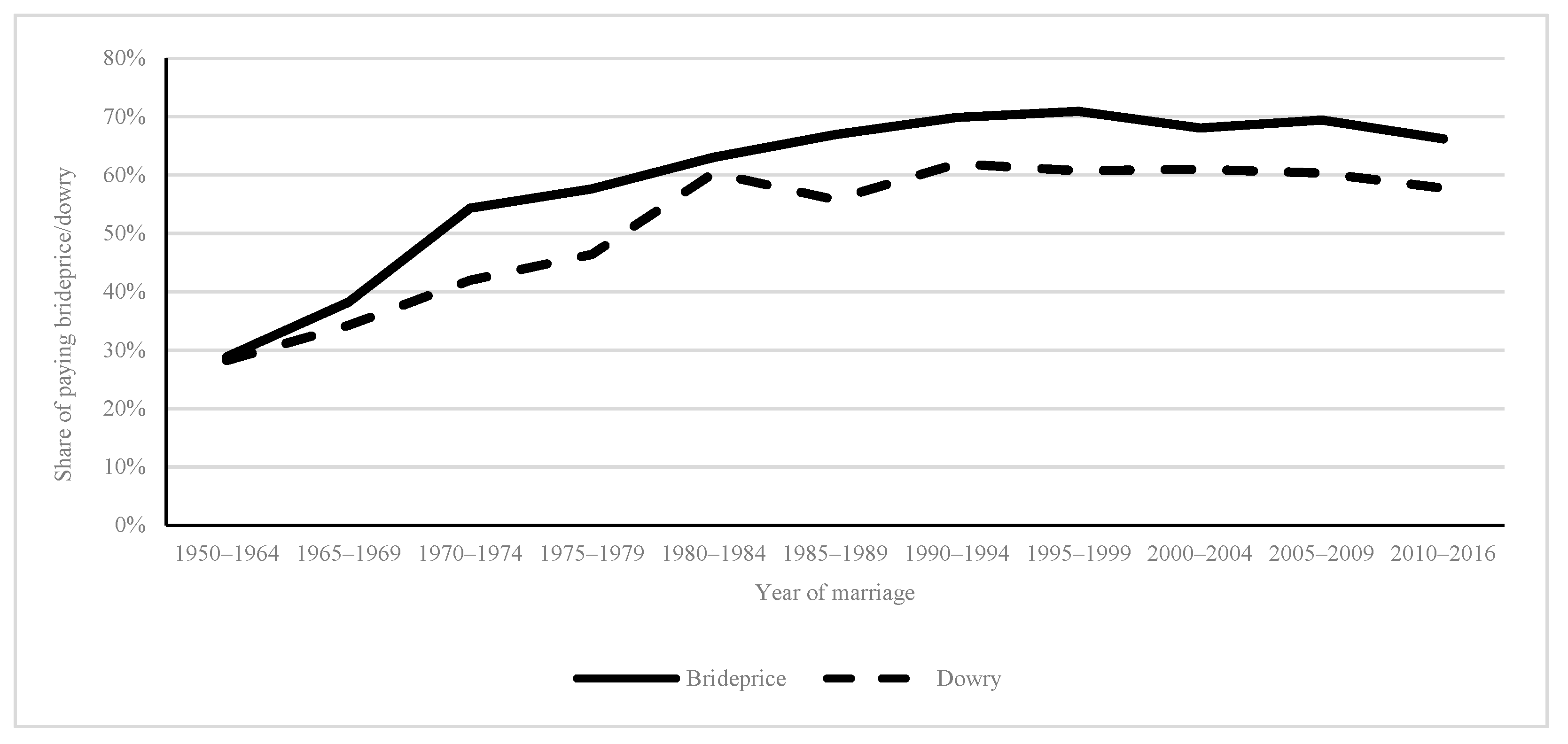

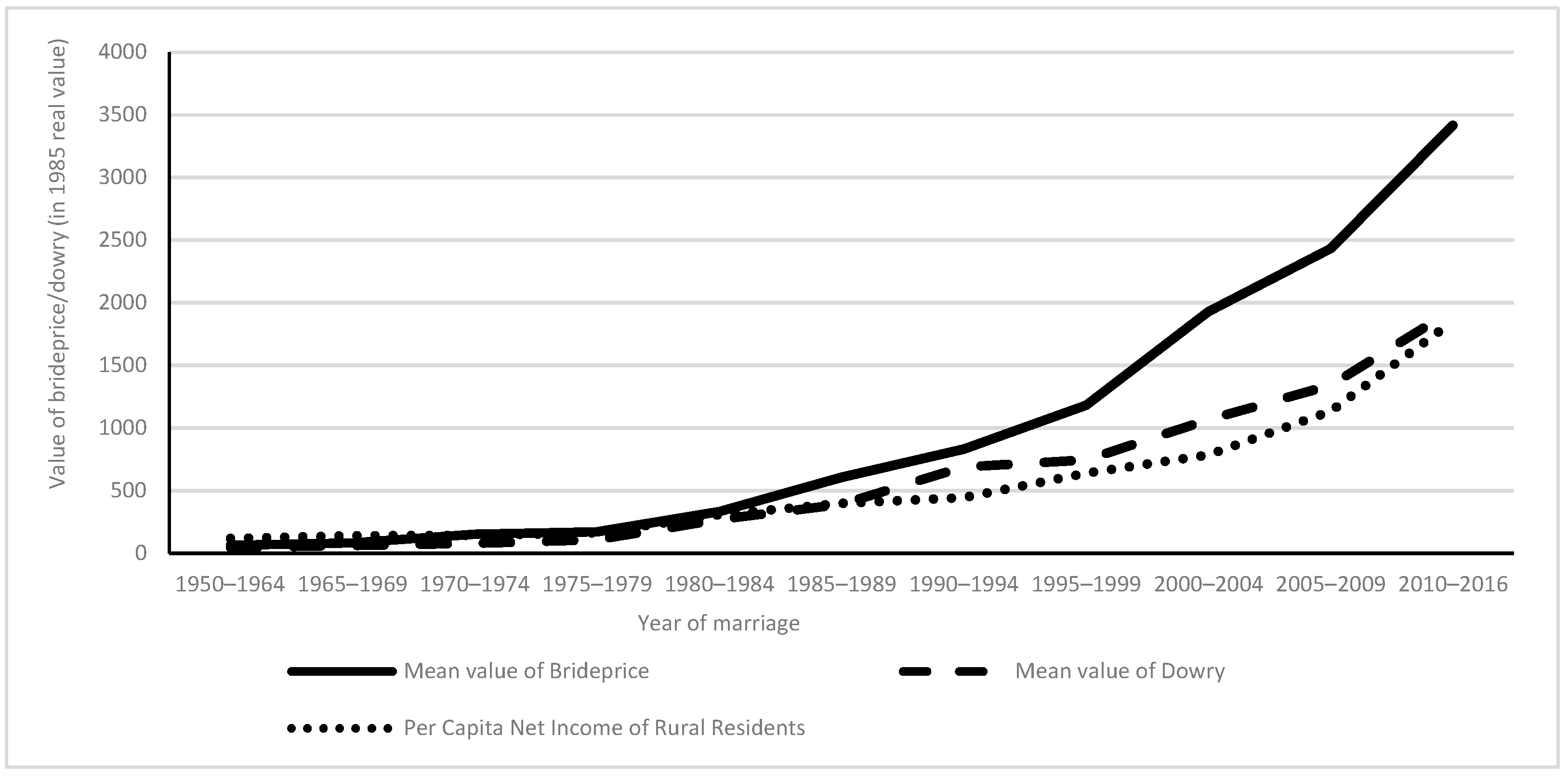

Therefore, the goal of this study is to estimate the correlation between matching types and marriage payment behaviors in rural China. Specifically, we first analyze the trends of brideprice and dowry in rural China from 1950 to 2015 based on field survey data with a nearly national representative sample. We then evaluate the impact of love match on brideprice and dowry. Finally, we explore the heterogeneity of love match on brideprice and dowry with different marriage distances.

Our work contributes to literature in the following ways. Firstly, our research adopts data covering nearly 70 years with a nearly nationally representative sample which will enrich literature by analyzing long trends of marriage payment in rural China. Secondly, to our best knowledge, this is the first study to assess the correlation between love match and brideprice/dowry based on relatively rigorous empirical means. Thirdly, it also investigates the heterogeneity of love match on brideprice/dowry between different marriage distances. The results have implications to further deduce burden due to marriage payment in rural China, even for other developing countries.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents conceptual framework and literature review.

Section 3 introduces the methods, including sampling and data collection, definition of variables, and model specification.

Section 4 shows descriptive analysis.

Section 5 presents and discusses the results of empirical analysis. The conclusion and implications are in

Section 6.

2. Conceptual Framework and Literature Review

Individuals or households maximize their expected utility when becoming married, given their own human capital and family background [

21]. We simply categorize the expected utility of marriage into two types: emotional benefit including expected emotional support, such as harmony of the marriage felt by the groom/bride, and non-emotional benefit, which contains expected economic gains, net marriage payment and risk prevention [

12,

22]. There are many different combinations of these two kinds of benefits on the indifference curve of maximum utility. However, there are preference differences in the combination of these two kinds of benefits between different decision makers with the same utility [

23]. It indicates that the marginal rate of substitution between emotional benefit and non-emotional benefit is different between a love match and an arranged marriage. If we define the U as the expected utility of a marriage union, we have:

Why do couples and their parents have different preferences? Firstly, marriage directly affects the welfare of their parents rather than simply forming a new family of two individuals. Many “goods” produced by the couple, including their labor market income, household goods and services, children, and elder care, can be sharable and beneficial to their parents [

22,

24,

25]. Elderly care is mainly provided by adult children, especially in rural China. When parents are the primary decision makers, they will take the non-emotional benefit as the principal factor to make sure they can enjoy the parental goods [

22,

26]. The emotional attraction is not a parental good, which will be undervalued by parents. The love-match males care more about the attractiveness of their wife and the harmonious of their marriage than those of arranged marriage [

22,

26,

27]. Secondly, marital search is costly and primary decision makers will bear most of the search cost. It is difficult for parents to estimate the emotional output, so they can only use quantifiable economic criteria as the screening criteria to reduce the search cost [

12]. Therefore, different preferences of decision makers lead to different factors driving the maximization of utility function.

Expected economic output of a marriage can be regarded as “goods” produced by the couple. Based on the evidence from numerous studies, spouse human capital determines household productivity. Human capital, such as education, age, health, and training, is an important drive of income growth and determines individual productivity [

28]. Let

≥ 0 and

≥ 0 denote the human capital of young man and woman, respectively.

and

jointly determine the total

(

), which reflects both the couple’s household production output and joint income.

Marriage payment is the outlay of money and/or goods as part of the marriage process. It includes brideprice, dowry and other expenses, such as wedding reception and house or property investments [

1,

29,

30,

31,

32]. These kinds of marriage payment are mutually substituted. Brideprice and dowry can be affected by the housing investment in rural China [

33]. In Vietnam, houses, wedding receptions, and expenditure of wedding ceremonies are also other forms of marriage payment to supplement brideprice or dowry [

31]. For example, the bride’s family will charge less for brideprice if the groom’s family builds a good wedding house, or the groom’s family will not claim dowry if the bride’s family decides to share the cost of the wedding reception.

Emotional benefit of a marriage can be interpreted as love or attraction between husband and wife and can be regarded as a function of love match [

22,

27]. It seems difficult to be accurately and quantifiably measured, compared with economic benefit and is often unpredictable based on commonly observed characteristics. Some previous studies, especially in modern western societies, used “whether a marriage ends up in divorce” as a natural measure of marital quality [

34,

35]. However, the extremely low divorce rate in rural China makes this measure less useful. Some other studies used harmony within a couple to measure emotional support in marriage [

22,

24,

35]. Regardless of many measurements of marital quality, there are ample evidences that love romance is strongly associated with marital quality. Huang et al. (2017) found that couples who marry in a love match have a higher degree of couple harmony, fewer conflicts, and higher emotional support among urban couples compared with those are parental matchmaking. They also found supporting and robust evidence for this conclusion using six provinces sample of urban and rural couples in China [

22]. Those who married for love are significantly happier and have higher marital satisfaction than those who have arranged marriage [

36]. Data showed significant fitness benefits of mating with partners of an individual’s own choice, highlighting elevated behavioral compatibility between partners with free mate choice [

37].

Marriage distance influences the bargaining of marriage payment. This comes from the two functions of marriage payment: insurance against the risk of marital breakdown and compensation for the loss of labor in original family [

8]. Mixed results were found in previous studies. Those who leave the original intermarriage circle will face greater marital risks, including family abuse, social, cultural, and economic difficulties [

38,

39,

40]. However, other studies found that a female migrant might marry a man distant from her natal family in exchange for a more desirable location and an improvement of her economic well-being. The man has achieved the goal of marriage and augmented his household’s labor supply at a cheap price [

41,

42].

This seems to make sense logically. A couple from the same area, within the same intermarriage circle, with similar personal characteristics and living habits, are more likely to have less conflict and stay married. As marriage distance increases, the similarity diminishes and the risk of divorce increases. However, more couples will tolerate each other to maintain the situation of marriage because brides are completely separated from their original living environment with a long marriage distance, which decreases the risk of divorce. Logically, wives’ returns to their original families after marriage are more negatively correlated with marriage distance. A bride with a smaller marriage distance is still able to provide economical and emotional support to her natal family after becoming married, such as helping her parents do domestic work and giving goods or money to her parents. On the contrary, the further a bride marries, the lower her family’s expectation of reward and help after her marriage.

The number of siblings has an impact on marriage payment. Under the traditional culture in China, parents have the responsibility and obligation to give all their children economic resources to promote their marriage [

43,

44]. Resource dilution theory holds the belief that the number of children determines the number of resources available to each child in a family since the resources in a family are limited [

15,

43,

44]. If males’ family has more children, females’ family will change its pricing strategy and try to become more resources for her daughter and son-in-law to avoid being diluted by males’ siblings. Roy (2015) found that parents appear to compensate their daughters by giving daughters higher dowries because of their son’s exploitation of family resources [

15]. Wei and Jiang (2017) found that there is intragenerational dilution exploitation between brothers using the data collected from 241 villages of nine provinces in China in 2014 [

45]. Some case studies also found that intragenerational exploitation existed, which refers to the competition between brothers within the family or the exploitation of brothers over sisters [

2,

45,

46,

47].

Based on above framework and literature review, groom

and bride

have,

where,

Based on the conceptual framework, we proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Love-match couples are less likely to pay brideprice and dowry when they become married than those of parental matchmaking.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Love-match couples pay smaller amount of brideprice and dowry when they become married than those of parental matchmaking.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). There is a heterogeneous effect of love match on brideprice and dowry with different marriage distances.

6. Conclusions and Implications

This study examines the correlation of love match (versus parental matchmaking) and marriage payment behaviors by adopting Logit, Tobit, and SUR models based on data from 1950s to 2010s in rural China. We also analyze the role of marriage distance in this relationship. Some robust and interesting conclusions are yielded.

Love match is associated with less likelihood of paying brideprice and dowry and smaller amount of brideprice and dowry. There is a significant inverted U-shaped relationship between marriage distance and the likelihood of paying brideprice and dowry and the value of brideprice and dowry. For short-distance marriage, an increase in the marriage distance also increases the pressure on bidirectional cash transfers. Love match, however, prevent the increased likelihood of paying brideprice and dowry and decreases the value of brideprice and dowry when a long marriage distance is involved. The results indicate that the cohort of marriage year and region are two important factors in marriage payments in rural China.

Our study has some implications in the village governance of recent rural China. “Poverty caused by marriage” has been common in rural China, and the Chinese government is determined to address the problem of the sky-high brideprice [

58,

59]. However, it is difficult to achieve this goal by administrative decree due to complex cultural customs. Our study indicates that love match could be a helpful way and the government is suggested to strengthen the efforts on publicity and advocate love-match marriage. However, we cannot force two people to fall in love to solve the problem of high level of marriage payments, for love is one of the basic rights of human beings. However previous studies have shown that the vulnerable group is more likely to rely on parental matchmaking, such as low-educated rural people, and they should be paid more attention to reduce the phenomenon of “poverty caused by marriage”.

Although, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in China to systematically explore the relationship of love match and marriage payment behaviors, we are aware of the shortcomings of this study. First, due to data limitation, it can only analyze the correlation between love match and marriage payment but not their causal relationship. Advanced methods should be applied to yield robust results in the future when the appropriate data is available. Second, studying the effect of dowry on the well-being of a wife or the whole household is also very important, which will be the primary topic in our next study.