Enterprise Activity Modeling in Walnut Sector in Ukraine

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

- (1)

- (2)

- −

- Calculations were made for the scheme of walnut planting 10 × 10 m (100 seedlings per hectare);

- −

- Estimated cost of 1 high-quality seedling, which is zoned according to the local climatic conditions and begins to bear fruit starting from the 4th year of vegetation, EUR13;

- −

- Land rent, 55 EUR/ha;

- −

- Protection: the first two years, for 8 months, starting from the 5th year. for 3 months (during harvesting);

- −

- Watering: 1 time × 3 weeks × 30 L;

- −

- Period before fruiting lasts for 2 years.

Statistical Analysis

- −

- Summarizing all expenses (the structure of the expenses is covered in the assumptions 1 for the particular business model);

- −

- For establishing the overall amount of expenses for the particular business model during the investigated timeframe, we calculated the expenses of the progressive total;

- −

- Calculating the yield for each year of gardening until the 20th year allowing for the function (1) representing the yield of walnuts through the analyzed period;

- −

- Calculating the gross income allowing for the assumptions 1 that correspond to the particular business model;

- −

- For establishing the overall amount of the gross income for the particular business model during the investigated timeframe, we calculated the income of the progressive total;

- −

- Calculating of the profit were provided by subtraction of the gross expenses from the gross profit;

- −

- For establishing the overall amount of the profit for the particular business model during the investigated timeframe, we calculated the profit of the progressive total;

- −

- The calculation of profitability was carried out through the division of the gross profit by the gross expenses. The obtained results were represented in %.

- −

- calculations are based on yields per hectare of land;

- −

- the assumed tree density is 150 trees per hectare for the zoned variety of the low growing walnut;

- −

- kernel output under its primary processing is 45%;

- −

- the selling price of 1 kg of walnut kernel is EUR4.76;

- −

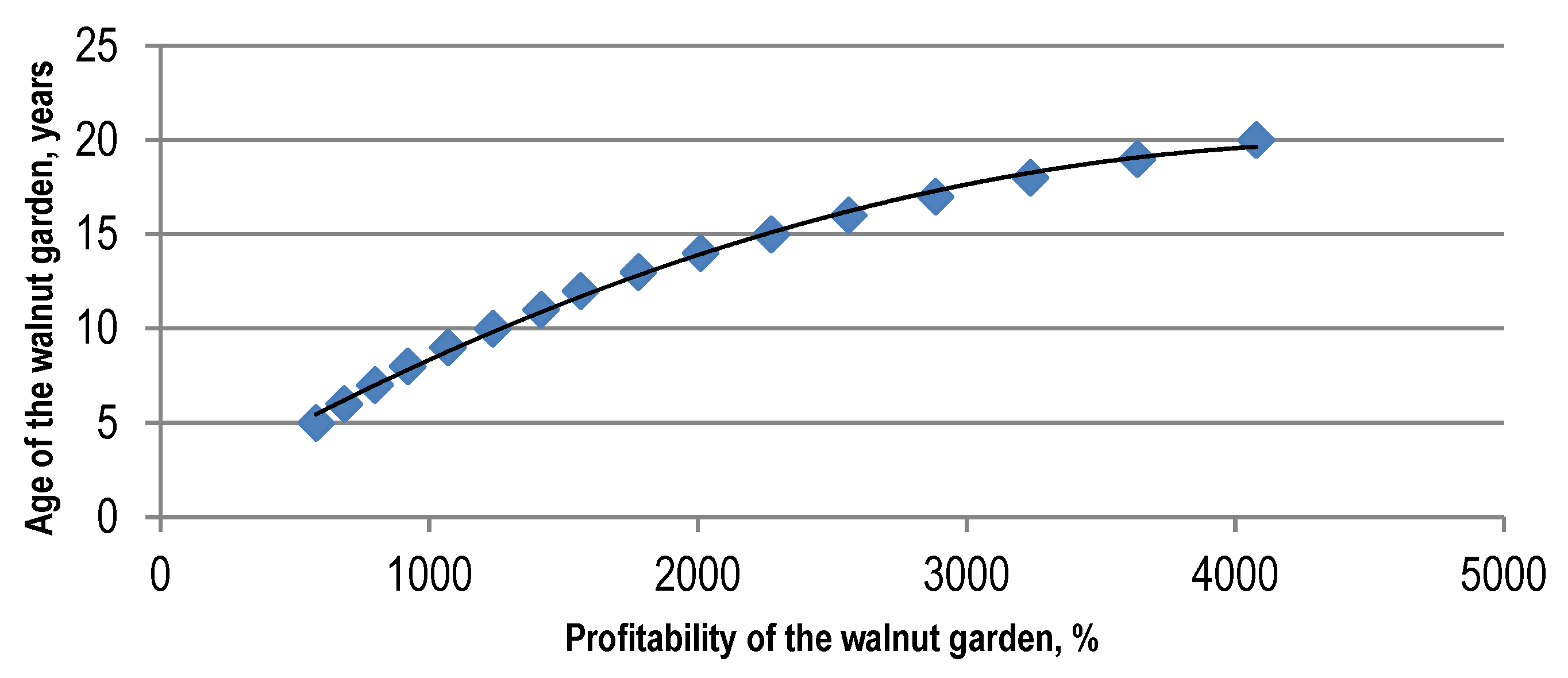

- the yield of the walnut garden changes by the exponential function according to the basic yield points corresponding to the age of the garden, for the data given in Table 1 (0.625 t/ha for the garden aged from 2 to 9 years, 2 t/ha for the garden aged from 10 to 20 years and 10 t/ha for the garden aged over 20 years), this function will have the following form:where y is the yield of the garden, x is the age of the garden. The reliability of approximation for this model is ;

- −

- expenses for sales and expenses for the primary walnut processing (calibration, shelling);

- −

- profitability is calculated as the ratio of gross profit (item 6) to the aggregate expenses for planting and maintaining a walnut garden (item 2).

- −

- Equipment costs involve the purchase, transportation, customs clearance and installation of the basic production equipment and include the cost and installation of the auxiliary production equipment;

- −

- Wages are calculated in the form of a single rate of monthly salary, regardless of the volume of production;

- −

- Production costs include electricity costs (tariff of 0.06 EUR/kW), 10 EUR/t of walnut kernel, materials and tools;

- −

- Organization expenses include the costs for meeting the requirements of the control services and obtaining permit documents for production.

- −

- Calculations are based on the data concerning the expenses;

- −

- Investments in the production of walnut kernel products are made in the second year of business operation and garden growth;

- −

- Oil output from walnut kernel is 42%;

- −

- The cost of processing walnut kernel into oil and oilcake is 0.57 EUR/ kg of walnut kernel;

- −

- The output of oilcake in oil production is 48%;

- −

- The selling price of 1 kg of walnut oil is EUR19;

- −

- The selling price of 1 kg of walnut oilcake is 0.63 EUR/kg (Table 6).

- −

- Organization expenses may consist of expenses for ensuring the conditions for the implementation of the signed contract for the walnut kernel processing into oil and oilcake;

- −

- Payment of the services for the walnut kernel processing includes payment for the transportation of raw materials and products of its processing, cargo loading services, preparation of raw materials for the processing, packaging, laboratory examination of the quality of obtained products, other production costs included in the processing of walnut kernel into oil and oilcake.

- −

- Conditions for product storage are provided at the farm; however, expenses for the given measures do not have a significant impact on the changes in the profitability and income of the project;

- −

- Contractual production of walnut oil and oilcake does not require additional investments (Table 8).

- −

- In the first year of activity, the enterprise spends money on the establishment of production;

- −

- Unshelled walnut is purchased for production;

- −

- The cost of primary walnut processing (shelling and sorting) is not taken into account;

- −

- Productivity of the equipment is 80 t per year of processed raw materials or 33.6 t of walnut oil and 38.4 t of oilcake due to the fact that the number of working days per year is 250 w.d./year, or 4.000 h (production is performed in two shifts);

- −

- Kernel output under primary walnut processing is 45%; therefore, to obtain 80 t of walnut kernel, it is necessary to purchase 180 t of unshelled walnut fruits.

- −

- When applying the given implementation form (Table 9).

5. Discussion

- −

- It is expedient to process walnut in accordance with its grade, since the confectionery walnut can be sold at a fairly high price without additional costs for further processing;

- −

- The profitability of the enterprise will be higher than in the proposed model if the sale price of walnut oil cake is taken into account;

- −

- Profitability of the enterprise will be higher if walnut shell is processed into biofuel or food for animal feeding and sold;

- −

- The increase in production capacity will lead to the increase in the income of the enterprise;

- −

- Development of B2B model into B2C model, development of the individual innovative functional food products from walnuts fruits, and access to the consumer market with its individual trademark can significantly increase the profitability of production. In this case, the cost analysis should be supplemented by the marketing costs, in particular, for sales.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Nuts&Dried Fruit. Nuts & Dried Fruits Global Statistical Review 2015/2016. 2016. Available online: https://www.nutfruit.org/files/tech/Global-Statistical-Review-2015-2016.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Statista. Production of Major Vegetable Oils Worldwide from 2012/13 to 2017/2018, by Type (in Million Metric Tons). 2018. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/263933/production-of-vegetable-oils-worldwide-since-2000/ (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Lutsiak, V.; Lavrov, R.; Furman, I.; Smitiukh, A.; Mazur, H.; Zahorodnia, N. Economic Aspects and Prospects for the Development of the Market of Vegetable Oils in a Context of Formation of its Value Chain. Montenegrin J. Econ. 2020, 16, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyulyov, O.; Chortok, Y.; Pimonenko, T.; Borovik, O. Ecological and economic evaluation of transport system func-tioning according to the territory sustainable development. Int. J. Ecol. Dev. 2015, 30, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Kachel, M.; Matwijczuk, A.; Przywara, A.; Kraszkiewicz, A.; Koszel, M. Profile of Fatty Acids and Spectroscopic Characteristics of Selected Vegetable Oils Extracted by Cold Maceration. Agric. Eng. 2018, 22, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botta, R.; Molnar, T.J.; Erdogan, V.; Valentini, N.; Marinoni, D.T.; Mehlenbacher, S.A. Hazelnut (Corylus spp.) Breeding., Advances in Plant Breeding Strategies: Nut and Beverage Crops, 157–219. 2019. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-23112-5_6 (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Ferrão, A.C.; Guiné, R.; Rodrigues, M.; Droga, R.; Correia, P. Post-harvest characterization of the hazelnut sector. Agric. Food Vet. Sci. 2020, 6, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, J.; Wang, W.; McGorrin, R.J.; Zhao, Y. Moisture Adsorption Isotherm and Storability of Hazelnut Inshells and Kernels Produced in Oregon, USA. J. Food Sci. 2018, 83, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, I.A.; Lucas, I.L.; Penna-Firme, R.; Strassburg, B.; Drosik, A.; Rubisz, L.; Kubon, M.; Latala, H.; Grotkiewicz, K.; Kubon, K.; et al. Survey-Based Qualitative Analysis of Young Generation Perception of Sustain-able Development in Poland. Agric. Eng. 2020, 24, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachev, H.B.H. Risk Management in the Agri-food Sector. Contemp. Econ. 2013, 7, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozhok, O.; Bozhok, V. Pro perspektyvy vyroshchuvannia horikha hretskoho na terytorii Ukrainy [On the pro-spects for growing walnut on the territory of Ukraine]. Naukovyi Visnyk NLTU Ukrainy 2017, 27, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kubon, M.; Krasnodebski, A. Logistic costs in competitive strategies of enterprises. Agric. Econ. 2010, 56, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishenin, Y.; Koblianska, I.; Medvid, V.; Maistrenko, Y. Sustainable regional development policy formation: Role of industrial ecology and logistics. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2018, 6, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotkiewicz, K.; Peszek, A.; Obajtek, P. Supply Chain Management in a Production Company. Agric. Eng. 2019, 23, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaura, M.; Kuboń, M.; Kowalczyk, Z.; Kwaśniewski, D.; Daniel, Z.; Kapela, K. Quality Assessment of Delivery in the Supply Chain Optimization. Agric. Eng. 2020, 24, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggetti, L.; Ferfuia, C.; Chiabà, C.; Testolin, R.; Baldini, M. Kernel oil content and oil composition in walnut (Ju-glans regia L.) accessions from north-eastern Italy. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 955–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanban-Esfahlan, A.; Jahanban-Esfahlan, R.; Tabibiazar, M.; Roufegarinejad, L.; Amarowicz, R. Recent advances in the use of walnut (Juglans regia L.) shell as a valuable plant-based bio-sorbent for the removal of hazardous materials. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 7026–7047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yermakov, S.; Hutsol, T.; Glowacki, S.; Hulevskyi, V.; Pylypenko, V. Primary assessment of the degree of torrefaction of biomass agricultural crops. In Environment. Technology. Resources, Proceedings of the International Scientific and Practical Conference; Rezekne Academy of Technologies, Rezekne, Latvia, 17–18 June 2021; 2021; Volume 1, pp. 264–267. Available online: http://elar.tsatu.edu.ua/handle/123456789/14974 (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Deng, X.L.; Zhao, Q.Z. Study on conformation and functional properties of walnut protein and its components. Mod. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 33, 48–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lisiecka, K.; Wójtowicz, A. The Production Efficiency and Specific Energy Consumption During Processing of Corn Extrudates with Fresh Vegetables Addition. Agric. Eng. 2019, 23, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Niemiec, M.; Komorowska, M.; Szeląg-Sikora, A.; Sikora, J.; Kuboń, M.; Gródek-Szostak, Z.; Kapusta-Duch, J. Risk Assessment for Social Practices in Small Vegetable farms in Poland as a Tool for the Optimization of Quality Management Systems. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.R.; Weinstein, D.E. Economic geography and regional production structure: An empirical investigation. Eur. Econ. Rev. 1999, 43, 379–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrantino, M.J. Using Supply-Chain Analysis to Analyse the Costs of NTMs and the Benefits of Trade Facilitation. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/zbw/wtowps/ersd201202.html (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Nang’ole, E.; Mithöfer, D.; Franzel, S. Review of Guidelines and Manuals for Value Chain Analysis for Agricultural and Forest Products. ICRAF Occasional Paper No. 17. Nairobi: World Agroforestry Centre. 2011. Available online: http://www.worldagroforestry.org/downloads/Publications/PDFS/OP11160.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- The European Union for Georgia. Walnut Value Chain Analysis in Ajara Region of Georgia. Tbilisi. 2016. Available online: http://environment.cenn.org/app/uploads/2017/04/Walnut-VCA-Report-eng.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Qammer, N. Analysis of Modernized Value Chain of Walnut in Jammu & Kashmir. Econ. Aff. 2018, 63, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, W. Analysis of the Walnut Value Chain in the Kyrgyz Republic Working Paper. Washington D.C: PROFOR. 2012. Available online: https://www.profor.info/sites/profor.info/files/Walnut_Value_Chain_KyrgyzRepublic_0.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Pandey, G.; Shukla, S.K. The Walnut Industry in India-Current Status and Future Prospects. Int. J. Fruit Sci. 2007, 6, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeląg-Sikora, A.; Sikora, J.; Niemiec, M.; Gródek-Szostak, Z.; Kapusta-Duch, J.; Kuboń, M.; Komorowska, M.; Karcz, J. Impact of Integrated and Conventional Plant Production on Selected Soil Parameters in Carrot Production. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Naik, H.R.; Hussain, S.Z.; Rouf, A. Development and popularization of broken walnut kernels products. Pharma Innov. J. 2019, 8, 475–476. [Google Scholar]

- Scherer, F.M.; Ross, D. Industrial Market Structure and Economics Performance; Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- World Trade Organization. Technological Innovation, Supply Chain Trade, and Workers in a Globalized World. Global Value Chain Development Report 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/dev/Global-Value-Chain-Development-Report-2019-Technological-Innovation-Supply-Chain-Trade-and-Workers-in-a-Globalized-World.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Jokić, S.; Moslavac, T.; Bošnjak, A.; Aladić, K.; Rajić, M.; Bilić, M. Optimization of walnut oil production. Croat. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 6, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Global Industry Analysts. Vegetable Oils—A Global Strategic Business Report. Press Relese. 2020. Available online: https://www.strategyr.com/pressMCP-2226.asp (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Jaćimović, V.; Adakalić, M.; Ercisli, S.; Božović, D.; Bujdoso, G. Fruit Quality Properties of Walnut (Juglans regia L.) Genetic Resources in Montenegro. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, G.; Owais, N.; Uzma, I. Scientific Processing of Walnuts Necessary for Amazing Health Benefits. J. Chem. Chem. Sci. 2016, 6, 783–793. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Li, C.; Cao, C.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Che, J.; Yang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, H.; He, G.; et al. Walnut Fruit Processing Equipment: Academic Insights and Perspectives. Food Eng. Rev. 2021, 13, 822–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radko, V. The Economic Aspects of Planting and Operation of the Greek Garden. Available online: https://uhbdp.org/images/uhbdp/pdf/Plodoov_vo_2016/1.3_Nuts.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Lanovenko, V. Golden Nut: How to Make Good in-Vestments in Walnut. 2016. Available online: http://agravery.com/en/posts/show/zolotij-gorisok-ak-vigidno-investuvati-u-voloskijgogih (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Verma, M.K. Walnut Production Technology. 2014. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282365700_Walnut_Production_Technology (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Wen, K.; Liang, S.L.; Yao, Z.Q.; Hao, H.; Liu, Z.L. Study on the processing technology of high protein defatted walnut powder. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2009, 12, 273–276. [Google Scholar]

- Tabasi, M.; Sheidai, M.; Hassani, D.; Koohdar, F. DNA fingerprinting and genetic diversity analysis with SCoT markers of Persian walnut populations (Juglans regia L.) in Iran. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 2020, 67, 1437–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Wang, L.; You, F.M.; Rodriguez, J.C.; Deal, K.R.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Chakraborty, S.; Balan, B.; Jiang, C.-Z.; et al. Sequencing a Juglans regia × J. microcarpa hybrid yields high-quality genome assemblies of parental species. Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perederiy, N.K.; Kuzmenko, S.; Labenko, O. Energy-saving technologies in agriculture of ukraine. Metod. Ilościowe Bad. Ekon. 2016, 17, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, C.W.; Kan, H.; Liu, Y. Comparative study of different walnut peeling processes. Farm Prod. Process. 2017, 11, 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Y.Q.; Chai, X.T.; Liu, M.K.; Liu, X.Z.; Li, J.; Gan, S.Y. Peeling of walnut kernel by vacuum freeze-drying: An analytical and experimental study. Chin. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. 2019, 39, 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- Asgari, K.; Labbafi, M.; Khodaiyan, F.; Kazemi, M.; Hosseini, S.S. Valorization of walnut processing waste as a novel resource: Production and characterization of pectin. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudryk, K.; Hutsol, T.; Wrobel, M.; Jewiarz, M.; Dziedzic, B. Determination of friction coefficients of fast-growing tree biomass. Eng. Rural. Dev. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalenko, N.; Kovalenko, V.; Hutsol, T.; Ievstafiieva, Y.; Polishchuk, A. Economic Efficiency and Internal Competitive Advantages of Grain Production in the Central Region of Ukraine. Agric. Eng. 2021, 25, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalenko, V. Economic Basis for the Creation of Fodder Base of the Enterprise. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Days 2018. Towards Productive, Sustainable and Resilient Global Agriculture and Food Systems: Proceedings, Nitra, Slovakia, 16–17 May 2018; pp. 840–850. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalenko, V.; Hutsol, T.; Kovalenko, N.; Zasada, M. Economic efficiency of production of herbal granules. Tur. Rozw. Reg. 2020, 14, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perederiy, N. Experience in financial planning in European countries. Sci. Bull. Natl. Univ. Life Eviron. Sci. Ukr. 2013, 181, 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Prishlyak, N. The experience of walnuts pro-duction in the world. Ekonomika. Finansy. Menedzhment Curr. Issues Sci. Pract. 2017, 1, 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P. Relationship Marketing: Kotler on Marketing. 2014. Available online: http://www.marsdd.com/mars-library/relationship-marketing-kotler-on-marketing/ (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Akca, Y.; Bilgen, Y.; Ercisli, S. Selection of superior persian walnut (Juglans regia L.) from seedling origin in Tur-key. Acta Sci. Pol. Hortorum Cultus 2015, 14, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Avanzato, D. Traditional And Modern Uses Of Walnut. Acta Hortic. 2010, 861, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajanana, T.M. Marketing practices and post-harvest loss assessment of banana var. Poovan in Tamil Nadu. Agric. Econ. Res. Rev. 2002, 15, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Global Hazelnut Market—Growth, Trends and Forecast, 2019–2024. Available online: https://cutt.ly/Yg3tMrX (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Global Tree Nuts Market 2019–2023. 2021. Available online: https://cutt.ly/6g3t1mR (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Hussain, S.Z.; Afshana, B.; Rather, A.H. Preparation and Storage Studies of Walnut Kernel Incorporated Rice Based Snacks. Int. J. Basic Appl. Biol. 2015, 2, 449–451. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley, Y.C. Carpathian Walnut. Alternative Tree Crops Information Series, 5. 2007. Available online: https://www.uidaho.edu/-/media/UIdaho-Responsive/Files/Extension/topic/forestry/ATC5-Carpathian-walnut.pdf?la=en&hash=94C07C90F1B070356F62039CB95173ED9E2CA146 (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Ivanyshyn, V.; Sheludchenko, L.; Hutsol, T.; Rud, A.; Skorobogatov, D. Mass transfer management and deposition of contaminants within car road zones. Environ. Technol. Resour. Proc. Int. Sci. Pr. Conf. 2019, 1, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, N.P.; Pha, P.T.L.; Trang, N.T.T. Effect of Drying and Roasting to Antioxidant Property and Stabil-ity of Dried Roasted Walnut (Juglans regia). J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2019, 11, 1693–1697. [Google Scholar]

- Market Overview of Hazelnut in Ukraine. Tridge.com: Website. Available online: https://www.tridge.com/products/hazelnut-in-shell/UA (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Shifting Trends in Global Tree Nut Market. Available online: https://www.globalaginvesting.com/gai-gazette-shifting-trends-global-tree-nut-markets/ (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Tree Nuts: World Markets and Trade. USDA. Available online: https://cutt.ly/rg8YFjY (accessed on 15 November 2021).

| Garden Age, (Years) | Tree Density in the Garden, Trees·ha−1 | Average Yield, t·ha−1 |

|---|---|---|

| 5–9 | up to 100 | up to 0.25 |

| 100–125 | 0.625 | |

| 125–150 | up to 1 | |

| 10–19 | up to 100 | up to 1.5 |

| 100–125 | 15–2 | |

| 125–150 | 2–2.1 | |

| 20–100 | up to 100 | up to 3 |

| 100–125 | 8–10 | |

| 125–150 | 10 and more |

| Item of Expenses | Amount, EUR | Share of Expenses in the General Structure, % |

|---|---|---|

| Wages with charges | 4.47 | 18.01 |

| Fuel | 1.82 | 7.35 |

| Saplings | 12.7 | 51.2 |

| Spraying | 0.59 | 2.36 |

| Mineral fertilizers | 1.22 | 4.94 |

| Organic fertilizers | 0.89 | 3.61 |

| Other expenses (land rent, irrigation, etc.) | 3.11 | 12.53 |

| Total | 24.8 | 100.0 |

| Technological Maintenance Operations | Costs, Thousand EUR | Share in the General Amount, % |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-planting soil preparation | 1.47 | 5.8 |

| Tree planting | 13.73 | 54.0 |

| Maintenance of the plantations, 1st year of vegetation | 1.73 | 6.8 |

| Maintenance of the plantations, 2nd year of vegetation | 2.71 | 10.6 |

| Maintenance of the plantations, 3rd year of vegetation | 2.76 | 10.8 |

| Maintenance of the plantations, 4th year of vegetation | 3.04 | 12.0 |

| Year of the Project Implementation | Expenses, Thousand EUR | Expenses of the Progressive Total, Thousand EUR | Yield, t/ha | Income, Thousand EUR | Income of the Progressive Total, Thousand EUR | Profit, Thousand EUR | Profit of the Progressive Total, Thousand EUR | Profitability, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 16.3 | 16.3 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −16.3 | −16.3 | −100 |

| 2 years | 3.03 | 19.32 | 6.10 | 13.07 | 13.07 | 10.05 | −6.25 | 332.06 |

| 3 years | 3.07 | 22.39 | 7.10 | 15.21 | 28.29 | 12.14 | 5.9 | 395.09 |

| 4 years | 3.04 | 25.43 | 8.30 | 17.79 | 46.07 | 14.74 | 20.64 | 484.81 |

| 5 years | 3.06 | 28.5 | 9.70 | 20.79 | 66.86 | 17.73 | 38.36 | 579.2 |

| 6 years | 3.09 | 31.58 | 11.30 | 24.21 | 91.07 | 21.13 | 59.49 | 684.72 |

| 7 years | 3.15 | 34.73 | 13.20 | 28.29 | 119.36 | 25.14 | 84.63 | 799.09 |

| 8 years | 3.23 | 37.96 | 15.40 | 33 | 152.36 | 29.77 | 114.4 | 921.12 |

| 9 years | 3.28 | 41.23 | 17.90 | 38.36 | 190.71 | 35.08 | 149.48 | 1070.78 |

| 10 years | 3.35 | 44.58 | 20.90 | 44.79 | 235.5 | 41.44 | 190.92 | 1237.2 |

| 11 years | 3.45 | 48.03 | 24.40 | 52.29 | 287.79 | 48.84 | 239.76 | 1416.57 |

| 12 years | 3.67 | 51.7 | 28.50 | 61.07 | 348.86 | 57.4 | 297.16 | 1564.14 |

| 13 years | 3.8 | 55.5 | 33.30 | 71.36 | 420.21 | 67.56 | 364.71 | 1779.39 |

| 14 years | 3.94 | 59.44 | 38.80 | 83.14 | 503.36 | 79.2 | 443.92 | 2010.39 |

| 15 years | 4.09 | 63.53 | 45.30 | 97.07 | 600.43 | 92.98 | 536.9 | 2274.03 |

| 16 years | 4.25 | 67.78 | 52.80 | 113.14 | 713.57 | 108.89 | 645.79 | 2561.69 |

| 17 years | 4.43 | 72.21 | 61.70 | 132.21 | 845.79 | 127.79 | 773.58 | 2885.48 |

| 18 years | 4.62 | 76.82 | 71.90 | 154.07 | 999.86 | 149.46 | 923.04 | 3237.86 |

| 19 years | 4.81 | 81.63 | 83.90 | 179.79 | 1179.64 | 174.97 | 1098.01 | 3635.65 |

| 20 years | 5.03 | 86.66 | 98.00 | 210 | 1389.64 | 204.97 | 1302.98 | 4078.77 |

| Item of Expenses | Amount |

|---|---|

| Basic expenses | |

| Purchase of equipment and its introduction into operation | EUR8600 |

| Organization expenses | EUR3200 |

| Overheads | |

| Wages with charges | 3800 EUR/year |

| Production costs | 10 EUR/t |

| Year of the Project Implementation | Expenses, Thousand EUR | Expenses of the Progressive Total, Thousand EUR | Yield, t/ha | Income, Thousand EUR | Income of the Progressive Total, Thousand EUR | Profit, Thousand EUR | Profit of the Progressive Total, Thousand EUR | Profitability, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 16.3 | 16.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −16.3 | −16.3 | −100 |

| 2 years | 18.62 | 34.91 | 6.1 | 21.96 | 21.96 | 3.34 | −12.95 | 17.96 |

| 3 years | 6.92 | 41.83 | 7.1 | 25.56 | 47.52 | 18.64 | 5.69 | 269.2 |

| 4 years | 6.93 | 48.76 | 8.3 | 29.88 | 77.4 | 22.95 | 28.64 | 331.17 |

| 5 years | 6.94 | 55.7 | 9.7 | 34.92 | 112.32 | 27.98 | 56.62 | 403.32 |

| 6 years | 6.95 | 62.65 | 11.3 | 40.68 | 153 | 33.73 | 90.35 | 485.57 |

| 7 years | 6.96 | 69.61 | 13.2 | 47.52 | 200.52 | 40.56 | 130.91 | 582.96 |

| 8 years | 6.97 | 76.58 | 15.4 | 55.44 | 255.96 | 48.47 | 179.38 | 695.35 |

| 9 years | 6.98 | 83.56 | 17.9 | 64.44 | 320.4 | 57.46 | 236.84 | 822.57 |

| 10 years | 7 | 90.56 | 20.9 | 75.24 | 395.64 | 68.24 | 305.08 | 974.56 |

| 11 years | 7.02 | 97.59 | 24.4 | 87.84 | 483.48 | 80.82 | 385.89 | 1150.93 |

| 12 years | 7.05 | 104.63 | 28.5 | 102.6 | 586.08 | 95.55 | 481.45 | 1356.27 |

| 13 years | 7.07 | 111.7 | 33.3 | 119.88 | 705.96 | 112.81 | 594.26 | 1594.94 |

| 14 years | 7.1 | 118.81 | 38.8 | 139.68 | 845.64 | 132.58 | 726.83 | 1866.15 |

| 15 years | 7.14 | 125.95 | 45.3 | 163.08 | 1008.72 | 155.94 | 882.77 | 2183.59 |

| 16 years | 7.18 | 133.13 | 52.8 | 190.08 | 1198.8 | 182.9 | 1065.67 | 2545.79 |

| 17 years | 7.24 | 140.37 | 61.7 | 222.12 | 1420.92 | 214.88 | 1280.55 | 2970.03 |

| 18 years | 7.29 | 147.66 | 71.9 | 258.84 | 1679.76 | 251.55 | 1532.1 | 3448.96 |

| 19 years | 7.36 | 155.03 | 83.9 | 302.04 | 1981.8 | 294.68 | 1826.77 | 4002.71 |

| 20 years | 7.44 | 162.47 | 98 | 352.8 | 2334.6 | 345.36 | 2172.13 | 4640.32 |

| Item of Expenses | Amount |

|---|---|

| Basic expenses | |

| Organization expenses | 320 EUR |

| Overheads | |

| Payment for services for the walnut kernel processing | 320 EUR/t |

| Total | |

| Year of the Project Implementation | Expenses, Thousand EUR | Expenses of the Progressive Total, Thousand EUR | Yield, t/ha | Income, Thousand EUR | Income of the Progressive Total, Thousand EUR | Profit, Thousand EUR | Profit of the Progressive Total, Thousand EUR | Profitability, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 16.30 | 16.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −16.30 | −16.30 | −100.00 |

| 2 years | 3.90 | 20.19 | 6.10 | 21.96 | 21.96 | 18.06 | 1.77 | 463.54 |

| 3 years | 4.09 | 24.28 | 7.10 | 25.56 | 47.52 | 21.47 | 23.24 | 525.35 |

| 4 years | 4.26 | 28.54 | 8.30 | 29.88 | 77.40 | 25.62 | 48.86 | 601.62 |

| 5 years | 4.46 | 33.00 | 9.70 | 34.92 | 112.32 | 30.46 | 79.32 | 683.18 |

| 6 years | 4.69 | 37.68 | 11.30 | 40.68 | 153.00 | 35.99 | 115.32 | 767.88 |

| 7 years | 4.96 | 42.64 | 13.20 | 47.52 | 200.52 | 42.56 | 157.88 | 858.31 |

| 8 years | 5.27 | 47.92 | 15.40 | 55.44 | 255.96 | 50.17 | 208.04 | 951.39 |

| 9 years | 5.63 | 53.55 | 17.90 | 64.44 | 320.40 | 58.81 | 266.85 | 1044.55 |

| 10 years | 6.06 | 59.60 | 20.90 | 75.24 | 395.64 | 69.18 | 336.04 | 1141.84 |

| 11 years | 6.56 | 66.16 | 24.40 | 87.84 | 483.48 | 81.28 | 417.32 | 1239.28 |

| 12 years | 7.14 | 73.31 | 28.50 | 102.60 | 586.08 | 95.46 | 512.77 | 1336.08 |

| 13 years | 7.83 | 81.14 | 33.30 | 119.88 | 705.96 | 112.05 | 624.82 | 1431.00 |

| 14 years | 8.62 | 89.75 | 38.80 | 139.68 | 845.64 | 131.06 | 755.89 | 1521.19 |

| 15 years | 9.54 | 99.30 | 45.30 | 163.08 | 1008.72 | 153.54 | 909.42 | 1608.64 |

| 16 years | 10.62 | 109.91 | 52.80 | 190.08 | 1198.80 | 179.46 | 1088.89 | 1690.53 |

| 17 years | 11.89 | 121.80 | 61.70 | 222.12 | 1420.92 | 210.23 | 1299.12 | 1768.55 |

| 18 years | 13.34 | 135.15 | 71.90 | 258.84 | 1679.76 | 245.50 | 1544.61 | 1839.68 |

| 19 years | 15.06 | 150.20 | 83.90 | 302.04 | 1981.80 | 286.98 | 1831.60 | 1905.75 |

| 20 years | 17.07 | 167.28 | 98.00 | 352.80 | 2334.60 | 335.73 | 2167.32 | 1966.42 |

| Year of the Project Implementation | Expenses, Thousand EUR | Expenses of the Progressive Total, Thousand EUR | Volume of Raw Materials, t | Income, Thousand EUR | Income of the Progressive Total, Thousand EUR | Profit, Thousand EUR | Profit of the Progressive Total, Thousand EUR | Profitability, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 year | 188.01 | 204.31 | 180 | 648 | 648 | 459.99 | 459.99 | 244.66 |

| 2 years | 176.27 | 380.57 | 180 | 648 | 1296 | 471.73 | 931.72 | 267.62 |

| 3 years | 176.27 | 556.84 | 180 | 648 | 1944 | 471.73 | 1403.45 | 267.62 |

| 4 years | 176.27 | 733.11 | 180 | 648 | 2592 | 471.73 | 1875.19 | 267.62 |

| 5 years | 176.27 | 909.37 | 180 | 648 | 3240 | 471.73 | 2346.92 | 267.62 |

| 6 years | 176.27 | 1085.64 | 180 | 648 | 3888 | 471.73 | 2818.65 | 267.62 |

| 7 years | 176.27 | 1261.91 | 180 | 648 | 4536 | 471.73 | 3290.39 | 267.62 |

| 8 years | 176.27 | 1438.17 | 180 | 648 | 5184 | 471.73 | 3762.12 | 267.62 |

| 9 years | 176.27 | 1614.44 | 180 | 648 | 5832 | 471.73 | 4233.85 | 267.62 |

| 10 years | 176.27 | 1790.71 | 180 | 648 | 6480 | 471.73 | 4705.59 | 267.62 |

| 11 years | 176.27 | 1966.97 | 180 | 648 | 7128 | 471.73 | 5177.32 | 267.62 |

| 12 years | 176.27 | 2143.24 | 180 | 648 | 7776 | 471.73 | 5649.05 | 267.62 |

| 13 years | 176.27 | 2319.51 | 180 | 648 | 8424 | 471.73 | 6120.79 | 267.62 |

| 14 years | 176.27 | 2495.77 | 180 | 648 | 9072 | 471.73 | 6592.52 | 267.62 |

| 15 years | 176.27 | 2672.04 | 180 | 648 | 9720 | 471.73 | 7064.25 | 267.62 |

| 16 years | 176.27 | 2848.31 | 180 | 648 | 10368 | 471.73 | 7535.99 | 267.62 |

| 17 years | 176.27 | 3024.57 | 180 | 648 | 11016 | 471.73 | 8007.72 | 267.62 |

| 18 years | 176.27 | 3200.84 | 180 | 648 | 11664 | 471.73 | 8479.45 | 267.62 |

| 19 years | 176.27 | 3377.11 | 180 | 648 | 12312 | 471.73 | 8951.19 | 267.62 |

| 20 years | 176.27 | 3553.37 | 180 | 648 | 12960 | 471.73 | 9422.92 | 267.62 |

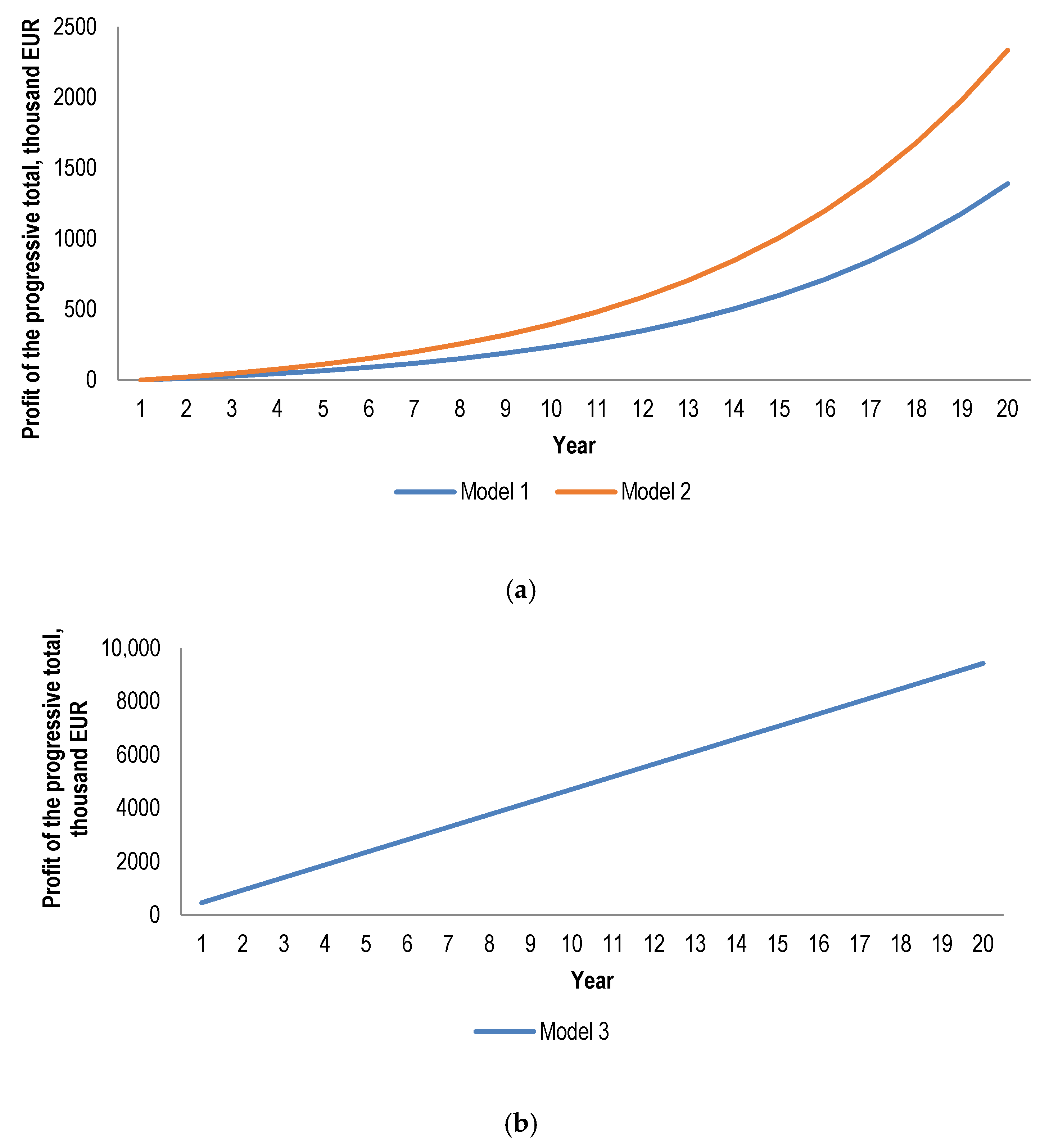

| Year of the Project Implementation | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation Form 1 | Implementation Form 2 | |||||||

| Profit of the Progressive Total, Thousand EUR | Profitability, % | Profit of the Progressive Total, Thousand EUR | Profitability, % | Profit of the Progressive Total, Thousand EUR | Profitability, % | Profit of the Progressive Total, Thousand EUR | Profitability, % | |

| 1 year | −16.3 | −100 | −16.3 | −100 | −16.30 | −100.00 | 459.99 | 244.66 |

| 2 years | −6.25 | 332.06 | −12.95 | 17.96 | 1.77 | 463.54 | 931.72 | 267.62 |

| 3 years | 5.9 | 395.09 | 5.69 | 269.2 | 23.24 | 525.35 | 1403.45 | 267.62 |

| 4 years | 20.64 | 484.81 | 28.64 | 331.17 | 48.86 | 601.62 | 1875.19 | 267.62 |

| 5 years | 38.36 | 579.2 | 56.62 | 403.32 | 79.32 | 683.18 | 2346.92 | 267.62 |

| 6 years | 59.49 | 684.72 | 90.35 | 485.57 | 115.32 | 767.88 | 2818.65 | 267.62 |

| 7 years | 84.63 | 799.09 | 130.91 | 582.96 | 157.88 | 858.31 | 3290.39 | 267.62 |

| 8 years | 114.4 | 921.12 | 179.38 | 695.35 | 208.04 | 951.39 | 3762.12 | 267.62 |

| 9 years | 149.48 | 1070.78 | 236.84 | 822.57 | 266.85 | 1044.55 | 4233.85 | 267.62 |

| 10 years | 190.92 | 1237.2 | 305.08 | 974.56 | 336.04 | 1141.84 | 4705.59 | 267.62 |

| 11 years | 239.76 | 1416.57 | 385.89 | 1150.93 | 417.32 | 1239.28 | 5177.32 | 267.62 |

| 12 years | 297.16 | 1564.14 | 481.45 | 1356.27 | 512.77 | 1336.08 | 5649.05 | 267.62 |

| 13 years | 364.71 | 1779.39 | 594.26 | 1594.94 | 624.82 | 1431.00 | 6120.79 | 267.62 |

| 14 years | 443.92 | 2010.39 | 726.83 | 1866.15 | 755.89 | 1521.19 | 6592.52 | 267.62 |

| 15 years | 536.9 | 2274.03 | 882.77 | 2183.59 | 909.42 | 1608.64 | 7064.25 | 267.62 |

| 16 years | 645.79 | 2561.69 | 1065.67 | 2545.79 | 1088.89 | 1690.53 | 7535.99 | 267.62 |

| 17 years | 773.58 | 2885.48 | 1280.55 | 2970.03 | 1299.12 | 1768.55 | 8007.72 | 267.62 |

| 18 years | 923.04 | 3237.86 | 1532.1 | 3448.96 | 1544.61 | 1839.68 | 8479.45 | 267.62 |

| 19 years | 1098.01 | 3635.65 | 1826.77 | 4002.71 | 1831.60 | 1905.75 | 8951.19 | 267.62 |

| 20 years | 1302.98 | 4078.77 | 2172.13 | 4640.32 | 2167.32 | 1966.42 | 9422.92 | 267.62 |

| Models | Indicators | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Achieving a Positive Profit | Year of Investment Return | Average Profitability Over 20 Years, % | Average Increase in Profitability Per Year over 20 Years, % | Profitability in the 20th Year | |

| Model 1 | 2 | 3 | 1592.40 | 174.98 | 4078.77 |

| Model 2 | |||||

| Implementation form 1 | 2 | 3 | 1512.18 | 211.85 | 4640.32 |

| Implementation form 2 | 2 | 2 | 1162.24 | 64.16 | 1966.42 |

| Model 3 | 1 | 1 | 266.47 | 1.15 | 267.62 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lutsiak, V.; Hutsol, T.; Kovalenko, N.; Kwaśniewski, D.; Kowalczyk, Z.; Belei, S.; Marusei, T. Enterprise Activity Modeling in Walnut Sector in Ukraine. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13027. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313027

Lutsiak V, Hutsol T, Kovalenko N, Kwaśniewski D, Kowalczyk Z, Belei S, Marusei T. Enterprise Activity Modeling in Walnut Sector in Ukraine. Sustainability. 2021; 13(23):13027. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313027

Chicago/Turabian StyleLutsiak, Vitalii, Taras Hutsol, Nataliia Kovalenko, Dariusz Kwaśniewski, Zbigniew Kowalczyk, Svitlana Belei, and Tatiana Marusei. 2021. "Enterprise Activity Modeling in Walnut Sector in Ukraine" Sustainability 13, no. 23: 13027. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313027

APA StyleLutsiak, V., Hutsol, T., Kovalenko, N., Kwaśniewski, D., Kowalczyk, Z., Belei, S., & Marusei, T. (2021). Enterprise Activity Modeling in Walnut Sector in Ukraine. Sustainability, 13(23), 13027. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313027

.jpg)