1. Introduction

Technological innovation, especially in the field of sustainability, has made it necessary to continuously update knowledge and develop skills to keep the possibilities for achievement continually expanding [

1]. New professionals need to be updated and increasingly trained in order to join the labor market. In the area of architecture and construction, new technologies are directly related to sustainability.

Thus, there is a need to develop these skills during academic life [

2], when students can participate in activities that provide them with appropriate preparation for the work environment. This includes using specific techniques for communicating with a team, relating, and presenting, as well as developing management (leadership) skills or other skills that are required by the market [

3]. Usually, these skills are developed outside the classroom [

4], through activities that aim to provide knowledge that is not offered by the monodisciplinary model of universities. This learning method is known as non-formal education [

5,

6].

In the context of sustainability, to offer an educational activity organized outside the existing formal system [

4] that aims to promote innovation and knowledge generation in systems for improving the energy efficiency of buildings, the integration of renewable energies, and the strengthening of sustainability in cities and buildings [

7] is very important for the development of future generations of architects and engineers. One of the main initiatives that promises to promote this training, outside the formal system of education, is the Solar Decathlon. This project, which is carried out as an optional activity by universities, is completely different from the academic programs normally implemented in the architecture and engineering fields, where the designs are usually conceived on paper and remain in two-dimensional forms. The building of zero-energy house prototypes, which provides a transversal and innovative approach to education by motivating students to put their knowledge into practice and apply their problem-solving, creativity, logical-thinking, financial-planning, teamwork, leadership, and organizational skills, etc., is exceptionally rare within academic programs [

8].

The Solar Decathlon (SD) is an international university competition founded by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) [

7] in 2000, in which universities design and build prototypes of high-efficiency homes [

9] powered by solar energy. The competition’s main objective is to train the future generation of engineers and architects, in addition to disseminating and implementing the concept of efficiency around the world [

10]. Consequently, it also involves the transfer of knowledge to industry professionals [

7], in order to instigate the application of certain techniques in their work.

The preparation for the event begins approximately two years in advance of the competition, when registration opens for universities to present their project proposals for the development of their houses. After the initial analysis of the proposals is caried out, based on technical innovation and content, organization and project planning, curriculum integration, and fund raising [

7], the teams are selected to participate in the competition, and they have until the beginning of the event to build a prototype of a high-efficiency house that is 100% powered by solar energy.

The houses are set up in a location known as the “solar village” (

Figure 1), where they compete in 10 different contests, which is why the competition is called a “Decathlon” [

11]. This location also welcomes thousands of people who are interested in visiting the houses and participating in the events and workshops prepared by the organization that enable them to discover new ways of living. A total of 1000 points are distributed between the ten contests, and the team that has obtained the highest score at the end of the event is the winner. The contests and the rules for each edition of the competition have varied over the years [

12], and experts in solar technology are invited to evaluate the houses [

7]. In addition to this, tests are carried out on the prototypes during the competition days, in order to prove the effectiveness of their efficiency. Based on these evaluations, at the end of the competition, the house with the highest score for the sum of the results of all the contests is the winner.

Although it varies between each competition, the teams usually have around 10–15 days before and 5 days after the event to assemble and dismantle the houses in the solar village. The future of the houses post competition is defined by each team. Some return to the university campus to serve as venues for studies, others are sold to recover the cost invested, and others are used for university housing [

7].

The first edition of the competition was held in 2002 in Washington D.C., in which 14 teams [

13] competed for the most efficient and sustainable home prototype. With more than 100,000 [

14] people in attendance, the event was considered a success and, after that, universities from other parts of the world began to express an interest in participating in the competition, as was the case for the Technical University of Madrid (UPM) [

15], which was the first international team to participate in the event, in 2005 [

16]. From that year onwards, the American competition started to be held every two years.

There was great interest in expanding the competition worldwide; for this reason, during the 2007 edition, an agreement was signed between the Spanish and the American Governments to create the Solar Decathlon in Europe (SDE) [

17].

Over the years, in addition to the North American (2002, 2005, 2007, 2009, 2011, 2013, 2015, and 2017) and European (2010, 2012, 2014, and 2019) editions, the competition also became headquartered in China (SD CHINA 2013 and 2018), the Middle East (SD ME 2018 and 2021), Latin America (SD LA 2015 and 2019), and Africa (SD AFRICA 2019) [

18,

19]. The event has expanded its global visibility and, for this reason, 20 competitions will have been held worldwide by 2022.

The Solar Decathlon is much more than a simple competition. It receives visitors, including students, academics, professionals, and citizens from all over the world. For example, in Madrid 2012 edition, the solar village received more than 220,000 visitors during the seventeen days that the event lasted [

20].

Almost two decades have passed since the first edition, with thousands of students and academics involved, 291 prototypes [

14] of sustainable houses developed, and numerous articles and theses published (based on different subjects, for example: industrialized construction systems [

21,

22]; passive and active design [

23,

24]; PV and thermal systems [

25,

26]; thermal storage [

27]; energy performance evaluation [

28,

29]; comfort conditions [

24]; materials [

30,

31]; user behavior [

32]; and education [

33]). With all these achievements, the Solar Decathlon has definitely impacted the world of sustainable construction and the development of new technologies and, in addition, it has proved to be an important tool to foster research and innovation. All of this shows that non-formal education projects, like the SD, play a very important role during the academic life of students, as they stimulate the development of competences based on the challenges of trial and error, and encourage the attainment of skills through group work. Subsequently, all this acquired knowledge serves to distinguish students when accessing the job market.

However, these possibilities are not all being fully optimized, and so this research arose from the hypothesis that the potential of the competition has not yet been fully exploited. It is essential to find tools that help to assess the performance of the competitions and propose improvements in order to expand the event to other parts of the world and, consequently, attract more people who can make a difference in the future.

Due to the absence of such information, in July 2019 a worldwide survey was launched, targeted at anybody who had had any contact with the SD. The purpose of this survey, which was completed in October 2020, was to collect data on the impact of the competition on people who were/had been involved in it, in the context of sustainability and energy efficiency.

The purpose of this research, in addition to exposing the insights obtained through the survey, was to present an analysis of the perceived impact of the competition on students in topics related to sustainability and energy efficiency. We believe that the opinions of those who have already experienced the competition can be applied in order to improve future editions. We also believe that the longevity of this event is very important for education in the sustainability field, because the more competitions are held, the more research, new technologies, and opportunities will be created to help develop a more sustainable society.

To fulfill the aforementioned objective, this article is organized as follows:

Section 2 (Materials and Methods) aims to explain how the survey was created and the methodology used to collate the responses from different types of participants in a single survey; In

Section 3, some of the data (in the form of graphs) obtained through the survey are detailed, along with analyses and discussions; In

Section 4, we discuss the pros and cons of the SD according to the results shown in the previous section; Finally, the fifth section concludes the article with a summary of what was presented and some additional questions.

2. Materials and Methods

Surveys are the most common research method used worldwide. They are very common in our daily lives because we are often asked to participate in surveys as electors, consumers, or users of services [

34]. A survey research method is considered suitable for gathering self-reported quantitative and qualitative data from a large number of respondents [

35]. The use of an online mechanism offers significant advantages over more traditional survey techniques [

36], because from a few clicks, it is possible to get an answer from a person who is anywhere in the world, at any time. In addition, these platforms help to collect and store responses quickly and safely. The authors used an online tool to implement the survey questionnaire.

As the competition involves several categories of the public, the survey was made suitable for any participant profile to answer it. To carry out the survey, we categorized the audience into five typologies, which were: former student decathletes (who were divided into three categories, BSc, MSc, and PhD students); professors and faculties from participating universities; organizers; professionals and companies; and citizens. The difficulty was that, as there were different types of respondents, there were different types of questions for each specific group within a single survey. In addition, the data from the questions of a global scope, which anyone could answer, needed to be separated according to participant categories, so that we did not obtain only the general result. This was because the different types of participants would hold different points of view, and separating the answers by participant category allowed for a faithful analysis of how the SD impacted each group specifically.

Therefore, we were able to carry out a single survey that met these needs and generated the results in the most appropriate and profitable way possible from a secure website, Typeform <

http://www.typeform.com> (accessed on 8 September 2020). The survey was optimized for display on mobiles, laptops, and tablets (

Figure 2), which were used by all participants to complete it [

37]. The survey link was initially distributed during the SDE 2019 competition in Szentendre (Hungary), before it was sent worldwide by e-mail. Participation was voluntary and respondents were assured that they would remain anonymous and that their responses would be reported only briefly.

The survey was focused on several aspects of the competition, such as the experience gained in the event, the evaluation of the contests, the SD’s impact, recommendations for improvement, and postcompetition perspectives. However, this article specifically analyzes the level of satisfaction of the participants, the general perception of the SD, and the impact the competition has in the field of sustainability and energy awareness.

The survey was divided into six parts. This division was made to separate all the subjects covered and to obtain the maximum number of responses, since it was possible for the responses to be saved at the end of each part, and thus we avoided losing information if the interviewee wanted to abandon the survey halfway. The survey was conducted in English and respondents were informed that the interview would take around 10 min. When using the internet or e-mail for research purposes, issues of privacy and consent are very important [

38]. The responses had a high level of data protection and confidentiality. Although there was no question that required the submission of personal data, all content generated was anonymous [

39], with each respondent given a code number.

The first part consisted of four classifying questions, which aimed to direct each type of audience to their specific questions. In this first part, the questions were multiple choice (MC), yes/no (Y/N), and unique questions (UQ) for which the interviewees had to choose an alternative from among many options. In the second part, with the typology of the audience separated into the five categories, the questions were of a general and opinionated nature. In this part, the questionnaire was of the selection type (SEL), for which the interviewee had to decide which option better suited the statement, and the assess type (AS), where they had to assess their satisfaction relating to any topic on a scale from 1 to 6, with 1 being the lowest score and 6 the highest.

Once the general questions were finished, the interviewee was directed to specific questions, which were divided into two parts. The questions were in MC, Y/N, and UQ formats, and were aimed at establishing what participation in the Solar Decathlon had developed and improved in the participant’s life in terms of knowledge, sustainability, awareness, and experience, etc.

At the end of the survey, there were additional questions. Before answering these questions, the interviewee was asked if they would like to continue the survey, since the main questions had already been answered and it would take another 10 min to finish answering. In this part they were requested to name 3 inspiring words (3W) and answer open questions (OQ), and the main objective was to obtain more detailed answers regarding suggestions to improve and innovate the competition and the perceived influence of the SD in the scope of social interest and media impact, etc.

From the organization chart below (

Figure 3), it is possible to better understand how the division of the survey worked. This article looks at the classification questions, the general questions, and several of the specific questions in part 1 in depth, as indicated in blue in

Figure 3. We decided to present in this research only the answers that would allow us to make a succinct and accurate analysis; therefore, the questions and full answers for these three parts of the survey can be found in the

Supplementary Material Questionnaire S1: SD Survey 2020.

The results presented in the next section are divided according to the three groups that are indicated in blue in

Figure 3. From these results it is possible to make a comparative analysis, and thus be able to identify the shortcomings of each area of the competition and create plans to improve the competition in a general and specific context for each group.

3. Results

In this section, some of the results of the survey are presented. The survey had a total of 392 responses. It is important to clarify that, except for the question related to the audience typology, which was used to direct the interviewee to the relevant questions, no question was obligatory. Therefore, the overall number of surveys answered does not always match the total number of answers for each specific question.

3.1. Classification Questions

The next four questions we discuss were classification questions. It was possible to obtain responses from participants of every competition that had been held, which was a challenge in itself, because there are no up-to-date databases of decathletes and other participants. Those who attended earlier competitions were especially difficult to reach through social networks, the main vehicle for communicating with former decathletes and professors.

The attendees of the European competitions (SDEs) provided the most responses. It is also worth highlighting the relevance of the fact that the attendees of the only competition held on the African continent provided the third largest number of responses. Extrapolating from this, it is possible to affirm that the survey received most of its answers from people who participated in recent competitions (in the last ten years).

Table 1, below, details the number of responses that the survey received for each competition.

The respondents were positive about the competition (

Figure 4). Of the respondents, 88% would have liked to compete again. Regarding the recommendation of the competition for future participants, 97% would have recommended taking part to others.

Considering that most people who responded to the survey were participants in recent editions (

Table 1), the results presented in

Figure 4 are important, because they show that even after almost twenty years of existence, the competition continues to impact the lives of the participants, and the vast majority not only recommend it to other people but also participate in future editions. This shows that there is great interest in the competition and demand to participate in future editions of the event.

For the only obligatory question in the entire survey, by which the respondents were divided into categories of participants, it can be seen that the vast majority of responses were from former student decathletes. The sum of the number of MSc, BSc, and PhD students reached almost 60% (59.69%) of the responses. It is important that most respondents were students, because one of the main objectives of this research was to analyze the impact of the competition in the educational sphere. The category with the second largest number of responses was professors and institutions, totaling 22.19%. Next were professionals and companies, organizers, and citizens, with 8.42%, 8.16%, and 1.53%, respectively (see

Table 2).

3.2. General Questions

The following five results were obtained from the general questions. After analyzing the results of the two questions in

Figure 4, we already expected that when respondents were asked whether the SD was a positive experience (see

Table 3), the responses would be favorable. For this question, the opinion that the competition experience was beneficial was unanimous in all five groups. This question aimed to find out the level of general satisfaction with the SD. This proved that regardless of the negative responses obtained in

Figure 4, the competition had a positive impact on the lives of those who participated.

In the next two questions, the respondents had to select one of eight options provided, which were: innovation and knowledge generation, environmental and sustainability awareness, fostering education, professional awareness, student employability, social awareness, media and social media impact, and all of the above.

As the respondents were able to select the option “all of the above”, we reflected the number of responses for this option as percentages, displayed on the graph beside each of the other seven categories. Each category of audience is represented by a specific color, and so it is possible to better visualize the responses of each category. The professionals and companies category and the citizens category were not included in the individual count of the following two charts because they provided few responses, and so, in order not to affect the comparison with the other three categories, they were only counted together with the sum of all responses.

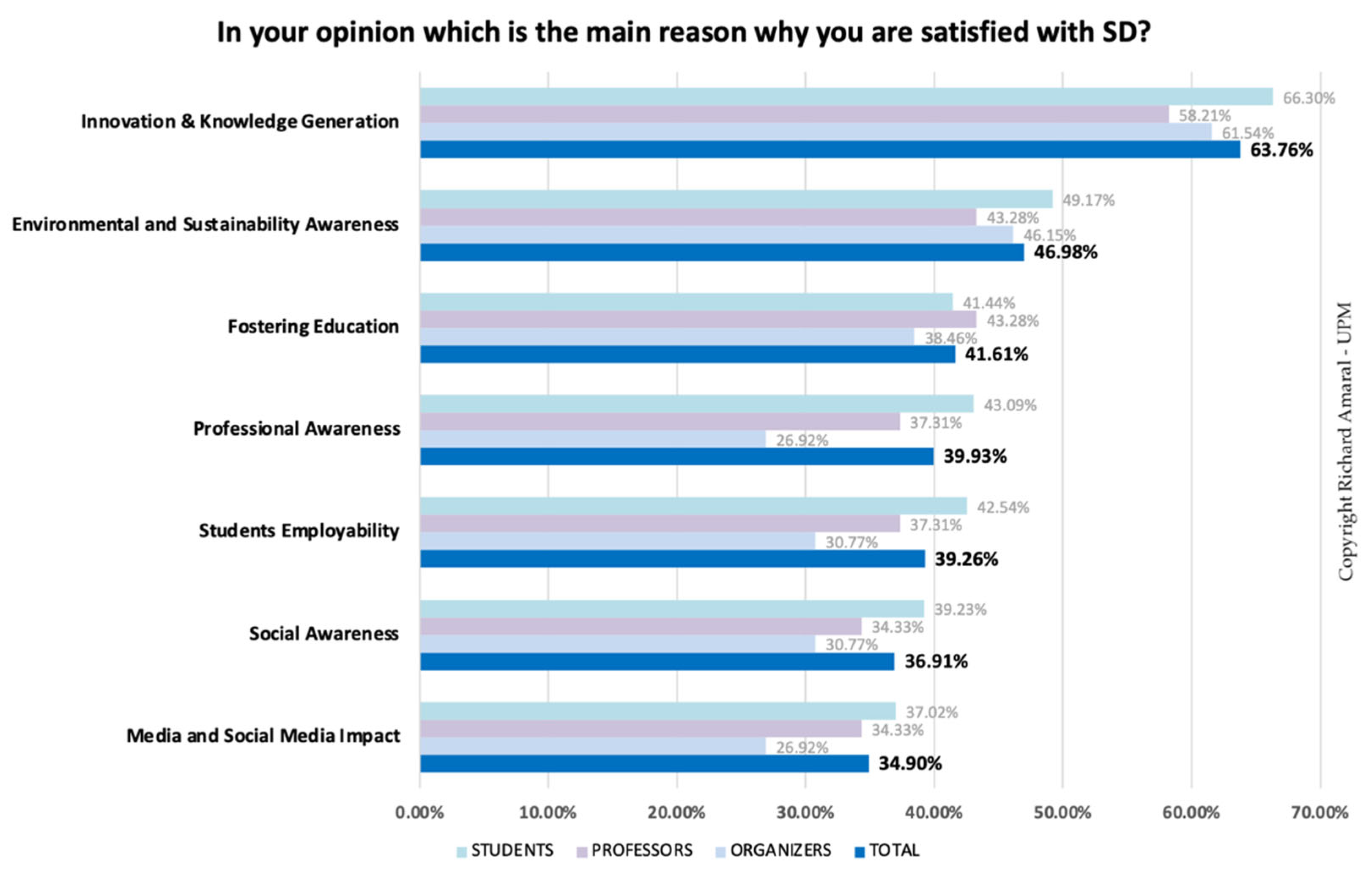

The question related to

Figure 5 aimed to identify the main objective fulfilled by the competition in the opinion of the interviewees. From analysis of the total result (the sum of the responses of the five groups), the category that stood out the most in this question was innovation and knowledge generation, chosen by 63.76% of the respondents. This same category was also considered the main reason for satisfaction with the SD in the individual opinion of each group, as shown in the graph. The results show that the event is indeed fulfilling its main objective, and that a non-formal education brings beneficial and complementary results to the academic journey of the students. The category that had the worst evaluation both in the opinion of the three groups individually and in the overall total of responses was the media and social media impact option (34.90%).

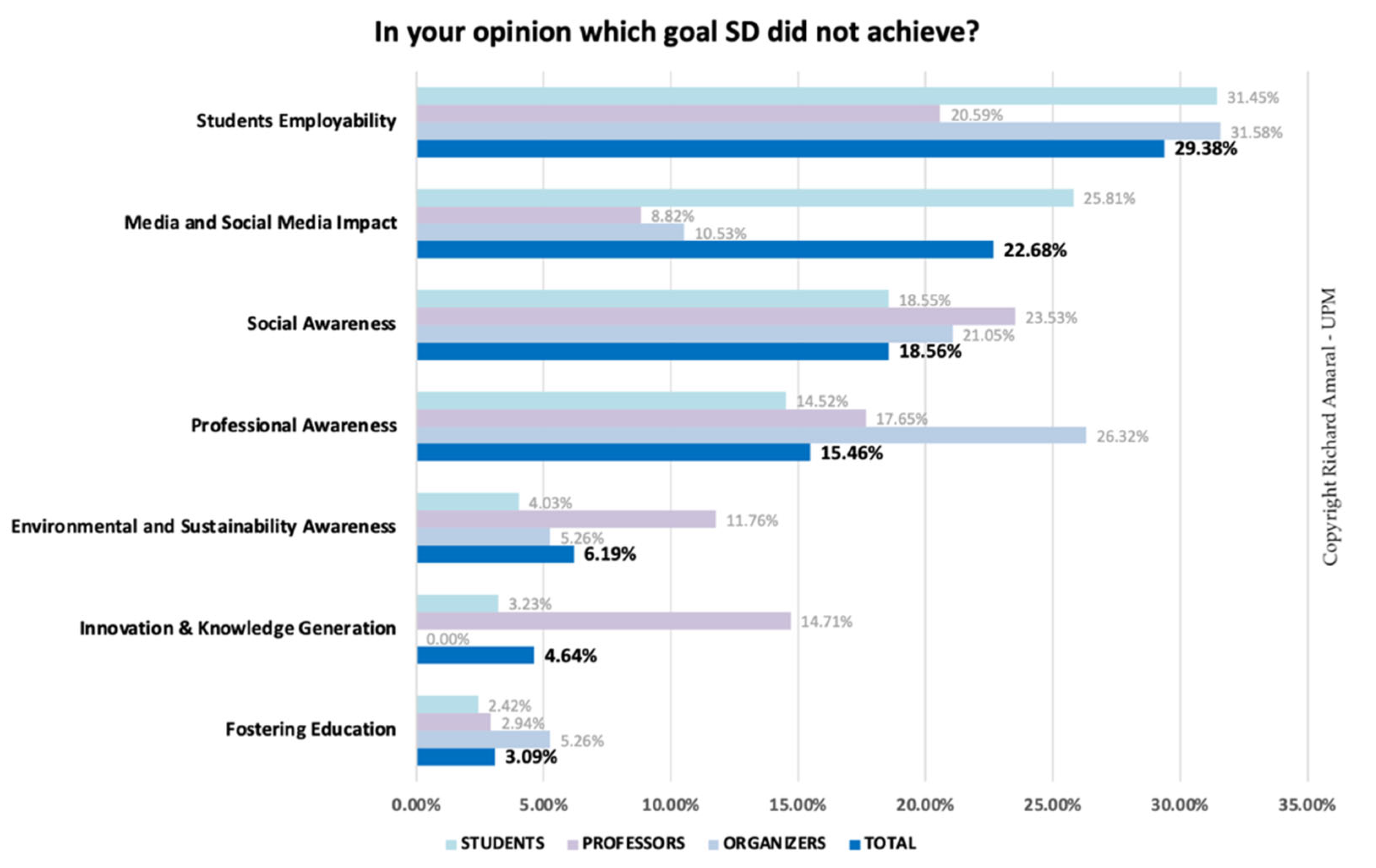

In

Figure 6, the question aimed to identify the main area of the SD in which it was necessary to work on improvement. Unlike in the last figure, the “all of the above” option was not represented because it received no responses, and so the percentages on this graph reflect the real value of the answers. In the general opinion, the objective that was not reached by the SD was student employability (29.38%). According to the analysis of the answers of the individual groups, students and organizers shared the same opinion (student employability). Professors and institutions believed that the goal not achieved by the SD was social awareness. The option “media and social media impact” was among the three highest scoring answer, confirming what was found in

Figure 5. Perhaps the two most voted categories for this question were related to each other, because the less publicized the event is, the less impact it has on people and the market. Thus, companies’ lack of knowledge about the event could be a factor that influences their decision not to hire a person who has taken part in this experience.

The last two questions in this part of the survey were of the evaluation type. In these, respondents had to evaluate on a scale from 1 to 6, where 1 was the lowest grade and 6 the highest. In the graphs below, it is possible to see the variation in the evaluations for each category and the average value.

In the case of

Figure 7, where the objective was to qualify the target levels achieved by the Solar Decathlon, six categories were suggested for evaluation. Three categories stood out and had a similar scoring average. These were: environmental and sustainability awareness, innovation and knowledge generation, and fostering education, with the average scores of 4.89, 4.88, and 4.84, respectively. This type of graph was also used to show the variation in the grades obtained. In the case of the three highest averages, the scores given by respondents ranged from around 4 to 6, as shown in

Figure 7. This result shows once again that the event’s commitment to developing innovation and promoting knowledge among participants is being well executed. All these aforementioned categories had a varied evaluation in the range of 4 to 6 points, and once again the dispersion could be explained by the differences in the outreach and impact of the different editions of the competition, which evoked some negative opinions that broadened the range of the sample. The category that had the lowest average was media and social media impact, with an average of 3.98 out of 6, which was to be expected, according to the results of

Figure 5 and

Figure 6.

In the last of the general questions, regarding the appropriate contests for the SD, it can be seen that the average scores were high in relation to the other questions. The best scores were for engineering and construction and energy efficiency. The category that had the lowest average was urban design, transportation, and affordability (

Figure 8).

Considering the conclusion of the second part of the survey, it is possible to state that competition brings favorable results in the field of educational innovation. This may be associated with the fact that the dynamic and transversal process that the competition promotes is an educational environment favorable to learning. Furthermore, the SD is an event that has an educational bias, and those who visit/participate in it are somehow related to this sector.

3.3. Specific Questions

The specific questions addressed the experience, awareness, knowledge, and skills that students obtained during participation, from the point of view of all audiences. In addition, they also portrayed the interviewees’ opinion regarding the contests in the fields related to education, energy awareness, sustainability, social awareness, and market and professional technical innovation. In this part, not only were the answers analyzed in a general scope, but the results were also obtained for each of the five categories individually.

In

Figure 9, regarding the opinion of the survey respondents on the impact of the events associated with the SD, the three best evaluated categories in general were: energy efficiency/saving awareness, sustainable awareness, and university, with an average score of 5.19, 4.96, and 4.90, respectively, out of a maximum score of 6.

Energy efficiency/saving awareness was the topic with the best rating in all five audience categories individually. This result is very interesting, because it shows that the five audience categories share the same thinking and that one of the main objectives of the event is recognized as the most impactful in the opinion of all types of participants. The topics that had the worst ratings (both in the overall total, and in the individual rating of each audience category) were childhood and teenagers and society/general public, with respective average scores of 3.58 and 4.05 out of 6. These two categories are somewhat related, due to the fact that both of them can be considered as relating to the visiting public. This result is remarkable, because it shows that, in the respondents’ opinion, the impact of competition does not reach this type of audience (which has, regarding its size, an important role).

In the evaluation of this chart, it is important to highlight the responses individually by group, which shows that the organizers were the ones who gave the highest averages (in seven of the nine topics).

Figure 10 concerns the question about the areas of awareness that the SD improved in the students’ lives. In this question, there were a total of 14 categories and each respondent had to choose 4. The option of “all of the above” was intentionally withheld, so that the respondents had to choose the four best proposed categories. According to the overall average, the four categories with the most votes were: energy efficiency, sustainability, passive strategies, and good teamwork. However, analysis of the responses by participant typology showed that opinions differed between some categories. For example, from the students’ responses, the four areas with the most votes were energy efficiency, good teamwork, sustainability, and innovation and emerging technologies, respectively.

According to the professors’ responses, the four options with the most votes were energy efficiency, passive strategies and sustainability (tied), and solar energy (PV and thermal), respectively. In the organizers’ opinion, the four most improved areas of awareness were sustainability, energy efficiency, innovation and emerging technologies, and passive strategies, respectively.

The topics of sustainability and energy efficiency appeared in the top four of all three categories, so they were the most relevant in the opinion of the interviewees, as illustrated in

Figure 10, which shows the consistency of the responses.

Overall, the category with the worst rating was carbon emissions (1.04%), even though the rating was not unanimous among the three voting typologies. Another category presenting a negative highlight was national media attention, with a vote percentage of 1.33%. As was seen in the analysis of the responses to previous questions, this is a topic that is always negatively highlighted by respondents.

As in the previous question, for the next question the respondents had to choose four of the ten categories related to the areas of experience developed by students participating in the SD (

Figure 11). Analysis of the general average of the responses shows that the four highlights were team working, communication, management, and leadership (21.23%, 12.74%, 12.08%, and 10.94%, respectively). Team working scored considerably higher than the category in second-best position, so it is the area in which students developed the most experience in the opinion of the respondents. The answer that had the lowest average rating was risk management, with 4.81%.

The results of this question confirm the importance of an event with a non-formal education approach. Team working, communication, management, and leadership are skills that are not learned in the classroom. Participation in an event that lasts two years can provide all the participants with these valuable skills that they can apply in their future jobs, benefitting their professional lives.

As regards the skills developed by the students (

Figure 12), nine categories were presented to be evaluated on a scale from 1 to 6. All nine categories were well evaluated and had a high average. The one that stood out the least was modelling and simulations, with a score of 4.55 out of 6. In the opinion of the respondents, the skill that was most developed in students was team working, with an average score of 5.43. This category was also a highlight of the responses to other questions, which shows that it is a positive aspect of the SD environment.

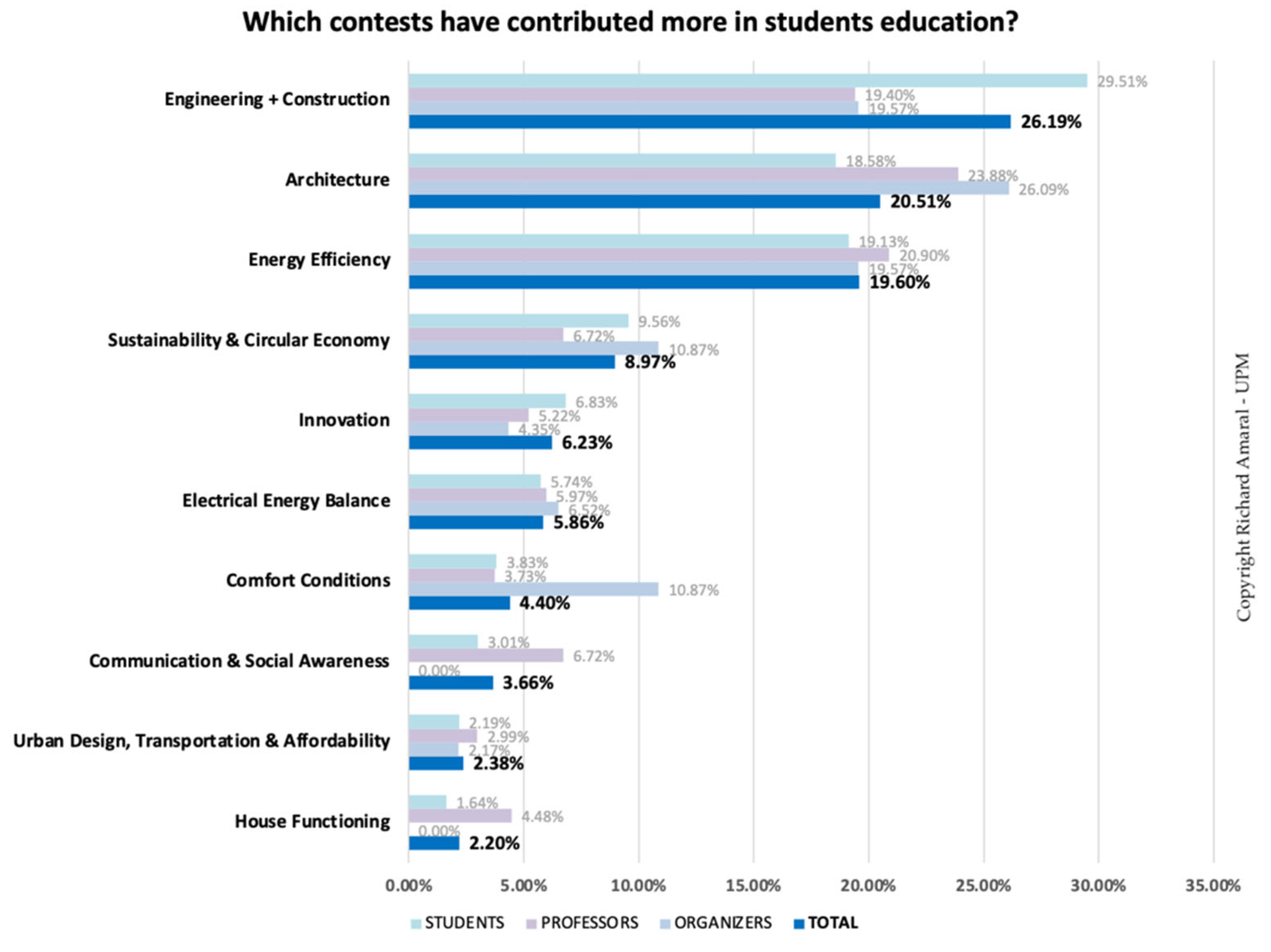

The next two questions (

Figure 13 and

Figure 14) were related to the SD contests. These were multiple choice questions, and the interviewee had to choose two contests as the answer to each question. The 10 contests evaluated were: architecture; engineering and construction; energy efficiency; electrical energy balance; comfort conditions; house functioning; communication and social awareness; urban design, transportation and affordability; innovation; and sustainability and circular economy. The evaluation of the contests was very important because, from the results we obtained, it was possible to consider each one individually and create solutions to improve the next editions of the competition. In addition, it was important to know the opinion of the students, professors, and organizers individually, because the contests impacted each category in a different way.

In

Figure 13, the two most frequently selected contests with respect to their educational contribution were the engineering and construction contest and the architecture contest, with voting percentages of 26.19% and 20.51%, respectively. There was a considerable gap between the first two contests, with the engineering and construction contest having a greater perceived contribution to education, although it was not chosen by the professors and organizers as the first option. It is worth mentioning that the energy efficiency contest also obtained a high number of votes and should be emphasized as well.

Event participants usually come from the fields of architecture, engineering, and construction. The results presented in

Figure 13 show that although the SD is a parallel event to university life, the content learned/experienced is always related to the scope of architecture/construction.

The two contests that had the worst performance in this question were the urban design, transportation, and affordability contest and the house functioning contest. Both had a very similar percentage of votes, 2.38% and 2.20%, respectively.

As regards the question about the contests that contributed the most in relation to the market and professional technical innovation (

Figure 14), the answers came only from two types of audiences (professors and organizers), as shown in the graph below. It is possible to see that the opinion varied between each audience. According to the average of the responses, the innovation contest and the engineering and construction contest were those with the highest number of votes (22.73% and 20.45%, respectively). According to the responses of the organizers, the energy efficiency and electrical energy balance contests were tied for second place, which shows that they are also significant in the scope of the market and professional technical innovation.

The contest that had the worst percentage of votes in the overall average was the sustainability and circular economy contest. Although this contest was the fifth-best-placed in the opinion of the organizers, it still had the lowest number of votes in the overall results, as the majority of the responses to this question were from professors (75% versus 25%).

The results presented in this section are tools capable of expressing the opinion of the participants relating to their experience of the Solar Decathlon.

4. Discussions

The results we presented indicate that the vast majority of respondents were satisfied with the competition, would recommend it to others, and would repeat the experience. The fact that most of the responses were from people who participated in the last ten years shows that the competition continues to have a positive impact many years after its inception. However, the fact that the survey had a large number of responses from participants of the most recent editions, and mostly from the European competitions, means that it may not provide consistent representation of the entire population of SD participants. Although the survey was answered by faculty advisors from the vast majority of the competitions, there were not very many responses by students from the first editions. One of the reasons for this was that many years have passed since the first edition, and the students could have forgotten their experiences. Usually, when more than six months has passed since the object of a study, the respondent begins to have difficulty remembering with the necessary precision [

40], and this can lead to inaccuracies in the final result. Knowing the importance of the opinion of the participants, the organizers of future competitions should carry out a satisfaction survey a maximum of 6 months after the event [

40], preferably right after the end, when the participants are still in the competition environment. In addition to obtaining a greater number of responses, the participants’ opinion would be more reliable as a consequence of the short time that had passed since their experiences.

We know from the survey that the innovation achieved and the knowledge developed via this experience were the most beneficial aspects in the interviewees’ opinion. It can be said that the training (learning and skills development) acquired by students during the competitions goes far beyond the final result. The students’ experience in working as a team, developing communication and leadership skills, and knowing how to create solutions in situations under stress are qualities that are stimulated by practical tasks—this knowledge is definitely not obtained within the classroom. This shows the relevance of an event that perpetuates non-formal education, and how important it is for students to have contact with this type of approach, because it is clear that there are always aggregating benefits for everyone involved.

We also believe that the SD’s potential does not finish at the end of the competition. There are many elements related to the SD that can be explored at universities, such as the implementation of courses, workshops, challenges, and projects for other students who did not have the opportunity to experience the competition but who could still enjoy the benefits of it. A motivated, committed, and clear-thinking faculty can improve the competition’s impact not just on their own students, but on hundreds of other students from their home universities. It is the faculty’s responsibility to keep updated in their discipline [

41], so another way to spread knowledge about the competition is through the work of academics, since teachers who have experienced the SD can to work and help other academics to incorporate this subject into their courses [

42]. The commitment of the entire university community [

43] can generate great benefits for the students and the institution.

In addition to the training, skills development, and the enhancement of students’ commitment to and social awareness of how to make buildings more efficient and sustainable from an energy point of view, the SD is indirectly premised on improving student employability by developing a generation of architects and engineers with a commitment to the environment and the needs of our society. Students who have at least some knowledge of sustainability are highlighted during their job search [

44]. This subject is directly related to companies and industries that should actively participate in the event. According to the interviewees’ opinion, the SD had a small impact on the employability of students. This fact may be related to the lack of attraction to and dissemination of the event among companies.

Further regarding the importance of disseminating the event, efforts must be made within the scope of media/social media. According to the responses of the interviewees to several questions, this aspect did not have a positive evaluation, showing that there is a deficit in this area. Tools should be implemented to improve the use of media/social media for the Solar Decathlon. This would cause an increase in people’s interest in participating in the SD. Thus, the greater the number of students, professors, sponsors, organizers, or even visitors involved in the event, the easier it will be to disseminate all the knowledge, awareness, innovation, and technological and sustainable impact that this event brings to its surroundings, which is the main objective of the SD.

It would be unrepresentative to draw a conclusion related to the SD’s social impact on the public by analyzing the data from the citizens who responded to the survey, as they constituted a very small portion of the responses. What can be said, according to the general opinion of respondents, is that the impact of the SD on society, on children, and on teenagers is something that should be improved. The creation of an appropriate atmosphere to arouse curiosity would encourage visitor involvement in a way that positively affects the event [

45,

46]. The implementation of activities that are attractive to young people is an important topic that should be considered, as the greater the number of visits from this group of people, the greater the dissemination of the event, as the connectivity between these people is vast.

5. Conclusions

Before this research was carried out, the opinion on the impact of the Solar Decathlon on the lives of those people who were involved in the event was unknown and undocumented. Only a few isolated competitions managed to capture this type of information. The realization of a survey that united the opinion of people from all over the world, including those who had participated in competitions held over 18 years ago, was very important, because it made it possible to capture the positive and negative impacts of the competition according to the opinion of those who lived the experience. Furthermore, it allows for the creation of plans to improve the performance of future competitions, which is especially significant now that the competition is about to turn twenty years old.

In these twenty years, there have definitely been several changes and advances in the field of sustainability and energy efficiency and it is important to use these, together with the knowledge gained from the experience of holding competitions, to create a plan so that the competition does not become obsolete and can continue to impact future generations.

We believe that the considerations we have presented can be used as a reference point for understanding the impact that the SD has on its participants, and also as a tool for the organizers of future editions. We think that the greater the longevity of the event, the better it is for students, in the context of education; for the market, in the areas of innovation and sustainability; and, consequently, for society. However, it is necessary to continue looking for new information and creating surveys that can generate new points of view, as was achieved in this article, in order to improve the impact of the competition in the future.