Abstract

This study attempts to explore the role of certification bodies on the formation of customer behavioral intentions. A structured questionnaire was used to collect data from hotel customers in Spain. The results of the structural equation modeling indicate that a certified hotel’s image will positively influence stay intention and willingness to pay a premium. At the same time, awareness of, and trust in, certification bodies both have a positive effect on a certified hotel’s image. Finally, awareness of certification bodies also exerts a positive effect on trust in certification bodies. The results offer hoteliers potential strategies for customer behavioral intentions enhancement.

1. Introduction

In the context of the tourism industry, where intangibility makes decision-making difficult for the customer, quality standards as a market signal are truly relevant [1], enhancing long-term innovation, competitiveness, and sustainability for tourism destinations and organizations [2]. In that sense, there is an increasing importance of sustainability in tourism and the need for new insights into how to improve competitiveness in the tourism sector as a whole [3]. Moreover, recent research in the field of tourism has highlighted the link between quality and sustainability of destinations, in terms of both management and customers’ perceptions [4,5]. Accordingly, the implementation of quality certifications would imply an improvement in the efficiency of the destination and, therefore, an increase in its sustainability.

Service providers can only maintain their competitive advantage by delivering high quality services to their customers in order to meet or exceed their needs [6]. Consequently, organizations must devise new quality management systems based on the principles of continuous improvement [7], due to their benefits on organizational performance. According to [8] (p. 919), certified quality systems “have helped thousands of companies the world over to establish quality management practices that are audited by independent third parties”. Academic literature has paid considerable attention to the benefits of these systems in many ways, such as reinforcing competitiveness, productivity and profitability [8,9]. From a general point of view, certified quality systems can help to connect to a specific group of consumers attracted by the sense of quality in service delivery. In the specific field of tourism, different authors have supported the effect of quality certifications as a source of competitive advantage and its impact on the performance of hotels [10,11] and destinations [12].

There are many different types of quality management systems, including quality management standards. The ISO 9001 quality management standard is the best-known set of standards through which companies can measure their quality management system. Achieving the ISO 9001 certification may help a company become recognized as superior to its competitors, can improve customer perception, and allow companies to compete in public contracts (due to their requirements). These standards have been widely accepted in companies from different countries, so that by the end of 2020 there were 1,593,031 companies certified worldwide and 48,960 in Spain [13]. Nevertheless, there is scarce information about the actual implementation of these quality certifications in the tourism sector, and different authors have highlighted how this topic is understudied [14].

The Institute for Spanish Tourist Quality (ICTE) has developed a tourist quality mark, the “Q system,” and a quality standard adapted to the hotel industry, known as standard UNE 182001 (the international equivalent of which is ISO 22483:2020) [15,16], to provide tourist companies with a quality management tool that has been tailored to their needs. The “Q system” of the ICTE is a self-regulatory standardization system that provides quality standards that are consistent with the ISO 9000 and ISO 14,000 families of standards [17].

Numerous studies have shown that quality management standards are equally important to production and tourism service businesses and that they may all benefit from having standards in place [18]. However, published studies have looked at service companies less than industrial enterprises, and there is a particular a gap in understanding in the hotel industry context. Although the importance of quality management standards in hotels has been recognized [19,20,21,22,23], there has been limited research that has addressed the role of third-party certifications and their relationships with the image of quality certified hotels. Hotels pursuing to improve their results cannot simply rely on quality but must also design inducements to attract customers [24]. In that context, the hotel image may play a key role due to the way in which it fosters behavioral intentions of the customers, mainly the intention to stay and the willingness to pay a premium [25].

The aim of the present study is to develop a model to explain the formation of customer behavioral intentions related to the image of a certified hotel, focusing on the central roles of the awareness of certification companies, and the trust in their signals of quality, as key determinants of a hotel’s image. Therefore, this article contributes to a better understanding of the impact of quality signals and quality certification on hotel image and behavioral intentions. The first section begins by reviewing the relevant literature on the role of certification bodies on the formation of customer behavioral intentions and briefly reviews awareness and trust in certification bodies as antecedents of certified hotel image. Furthermore, this section describes the methodology. The following section details the main findings, before the final section presents the main conclusions, managerial implications and future lines of research.

2. Conceptual Review of the Literature

2.1. Quality Standards and Certification Bodies

Quality standards are used in the tourist industry to demonstrate a company’s capacity to consistently produce products and services that meet consumer and regulatory criteria (For a detailed revision of hotel quality and its certification please see the studies developed by [26,27]). These standards, in particular, assist businesses in organizing and continuously improving their operating procedures. This is proven by implementing a set of documented operating procedures that explain how the firm’s operational activities and processes are carried out consistently [28]. As a result, certification serves to inform customers that the company has acquired third-party assurance.

As a result, other parties, such as certification agencies, are involved in the quality certification process. The certification bodies are in charge of overseeing the certification process as well as granting certificates. The selection of certifying organizations is a crucial step in the quality acceptance and certification process. Not just because various certifying bodies charge different rates for performing audits, but also because their services, especially the quality of their external auditors, are of varying quality [29]. According to existing research, certification bodies differ in terms of their objectives. In addition [30], choosing a less recognized certification body might jeopardize the legitimacy of quality standard implementation [29].

This study employs signaling theory to examine the importance of certifying bodies in the development of appropriate customer behavioral intentions in a hotel setting. As previously stated, signaling through certifying body selection helps to reduce information gaps between customers and suppliers [31]. Organizations that are certified by well-known bodies will be perceived to have a superior application of quality standards, thereby increasing consumer confidence. Firms can reduce the transaction costs of market exchanges in attracting consumers by communicating the importance of a certain quality certification implementation [32]. Because hotel companies compete on quality (among other things) [33], it is critical to understand the impact of quality signals in this market to enhance the long-term competitiveness and sustainability of tourism.

2.2. Certified Image and Customer Behavioral Intentions

Because of its influence on consumer behavioral decisions, the notion of a company’s image has piqued the interest of many researchers and practitioners in the tourist business [34,35,36,37]. In [38] the author defines image as an organization’s capacity to influence consumer views of its offerings. In [39] the author defines image as an individual’s idea, belief, or impression about a certain item, and how people react to that thing based on their perception of that object. The aggregation of numerous variables that represent and communicate the organizational identity is described as corporate image [40,41]. It is an individual’s assessment of the organization (consisting of a person’s beliefs, sentiments, and feelings) [42]. In [43] the author defines it as a consumer’s overall views of a company formed by the processing of data from many sources.

Since previously discussed, establishing favorable client intentions through a company’s image is a crucial aim for both hospitality and tourist firms, as these intentions will eventually boost customer retention and revenue [44]. When looking at individual decision-making processes, behavioral intentions are the closest antecedents of actual conduct, according to [45]. This means that researchers can anticipate certain actions with a high degree of accuracy based on intentions to engage in the activity in question. Behavioral intentions will be investigated in this hotel study by looking at two important dimensions: intention to stay and willingness to pay a higher cost at quality-certified hotels [38,46].

As previously stated, numerous studies have found that a favourable image has a beneficial impact on behavioral intentions in several service industries, including the hotel industry [34,35,36,37,47,48,49]. In the context of this study, a good (quality) certified image functions as a clear statement of a company’s dedication to quality and is an effective way to increase image distinction and earnings [10,26]. As a result, both quality procedures and quality certifications may be used to help a firm improve its image. As a result, the following research hypotheses are proposed in this study:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Customer perceptions of a hotel’s certified image positively affect their intentions to stay at quality-certified hotels.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Customer perceptions of a hotel’s certified image positively affect their intentions to pay a premium price for staying at quality-certified hotels.

2.3. The Effect of Trust in Certification Bodies on the Certified Image of a Hotel

Trust has become one of the key concepts in tourism and hospitality industry research [49,50,51]. According to [52], trust is defined as the expectations of one party that the exchange partner’s promises, whether written or verbal, are objectively credible and dependable. In [53] the author suggests that when trust exists, this entails the existence of both commitment and satisfaction from the part of the customer toward a specific company. Other studies agree to define trust as the reliability, honesty and goodwill exhibited by the supplier as perceived by the customer [54,55]. A definition offered by the marketing literature that is often cited by other researchers is the one offered by [56] (p. 651) who maintains that “trust is a generalized expectancy held by an individual that the word of another […] can be relied on”.

The definition of trust that will be adopted in this study is a combination of all the definitions stated above. For that trust to exist, hotels must emit different signals that reduce customer uncertainty and, in turn, increase their credibility. Previous studies in the academic literature [57,58] consider quality certifications as one of the most frequent signals uses by companies in order to be used by the consumer to infer the value of the product or service and its level of quality. In addition to this, [59] suggests that quality certifications add evaluative information of the service, always depending on the perception that the market has of the impartiality and independence of the certification body.

With regard to this, signal honesty [60] and signal credibility [61] are key terms in signaling theory. Considering that a hotel’s image has been defined as the customers’ total perceptions of the firm shaped by processing information from diverse sources, quality certifications act as a thoughtful communication of positive and imperceptible qualities that individuals access though different informational resources [62]. Consequently, those firms certified by certification bodies will be considered as having a better implementation of quality standards, hence, enhancing the perceived confidence from customers and thus improving their image. Therefore, the impact of quality certifications on the company’s image will be conditioned by the reliability perceived by consumers in these certification bodies. Consequently, if potential clients do not trust certification bodies (because they perceive them as inefficient or not neutral, for instance), they will not attribute higher quality to certified hotels, and the fact that the hotel is certified will not improve its image. Following these ideas, this study hypothesizes the following:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Customer trust in certification bodies positively affects a hotel’s certified image.

2.4. The Effect of Awareness of Certification Bodies on Hotels’ Certified Image and Trust in Certification Companies

Awareness reflects the salience of an object (e.g., firm, brand, product) in the customer’s mind [63]. It has a significant effect on consumer choices [64] and, therefore, is an important concept both in marketing and consumer behavior [65]. In academic marketing literature, the concept of awareness has been widely utilized as a component of (brand) knowledge [63,66]. In consumer behavior research, familiarity has also been studied as a component of organization knowledge [67].

By reducing customers’ perceived risk and information costs, awareness creates a platform to assure the legitimacy and standing of a company’s products and services. Furthermore, the reduction in ambiguity leads to greater quality expectations among consumers [68]. The firm becomes more prominent as awareness rises [69]. Memory, according to the associative network concept, is formed of nodes, which are described as stored information connected by weak connections [70]. The power of the business node in the minds of customers is reflected in awareness, which leads to variations in information processing [64]. In this regard, if clients are aware of a company, the likelihood that they have a good impression of it is higher [63,64,66]. In the context of this study, once customers recognize a certification body, they will give the organization meaning and form connections with it, not just with the certification body but also with the certified company. Because increased knowledge of a certification body stimulates the creation of such associations, it is reasonable to assume that increased awareness of a certification body will improve the perceived image of the firm that has been certified. As a result, our study was underpinned by the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Customer awareness of certification bodies positively influences a hotel’s certified image.

The sociological theory of trust proposed by [71] (consistent with the definition of trust that will be adopted in this study) is useful to underline the linkage between awareness and trust in the context of certification bodies. On the subject of this study and considering that trust is about expectations, customer trust in certification bodies will consist of familiarity (awareness) and trust about these organizations. Familiarity (awareness) precedes confidence and trust, and trust is only possible in a familiar (known) world [71]. Therefore, in the context of this research, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Customer awareness of certification bodies positively influences customer trust of these organizations.

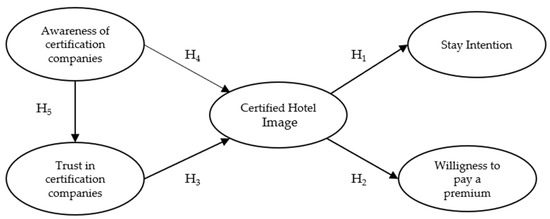

To summarize the explanation of the hypothesis, Figure 1 details the research model proposed.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3. Method

3.1. Measures

A questionnaire focused on visitors vacationing in Spanish hotels was designed to support the goals of this study. Participants were asked to assess their degree of agreement (or disagreement) with each item on a seven-point Likert scale, with one representing “strongly disagree” and seven representing “strongly agree”. To ensure that the participants felt able to express their opinions regarding these schemes, they were given broad knowledge about quality certifications, certification bodies, and their aims. Gender, age, level of education, employment, purpose of the trip, and past experience with a recognized hotel were among the demographic and travel characteristics of respondents sought in the survey. For all of our model’s constructs, we used measurement scales from prior research. Three questions, which were derived from research by [46], were employed to assess stay intention. The willingness to pay a premium was measured using three questions based on research by [46]. The image of certified hotels was assessed using a validated scale developed by [72]. The trust in certifying businesses was measured using four measures based on research by [73]. Finally, three questions were utilized to assess certification company awareness, based on a study by [74]. These instruments can be found in Appendix A.

3.2. Data Collection and Sample

To validate the research assumptions, a sample of hotel guests in Spain were questioned using a standardized questionnaire. Personal surveys of hotel customers over 18 years of age were conducted in the Autonomous Community of Cantabria (Spain) according to a structured questionnaire developed by the researchers. Interviews were carried out in the respondents’ homes to ensure their comfort and make sure that they took time to answer the questions calmly and thoughtfully. To prevent lethargy among the respondents, each interview was limited to an average of 10–15 min. Given the significant number of accredited hotels in Spain, as well as the country’s global leadership as a tourist attraction and the global reach of Spanish hotel chains, it was anticipated that this country might be an intriguing environment in which to test our study methodology.

The data collection was developed in collaboration with university students at the University of Cantabria undertaking the “Market Research” course there in the 2019 academic year. This subject is mandatory and is offered in several academic plans at the University of Cantabria. Every student has to develop real market research to pass the subject. Teachers in both courses provided a structured questionnaire to students (designed by the authors) to guide them in the fieldwork. In this sense, it is important to highlight that two out of the four authors of this paper teach this subject (with other teachers), so that they can supervise the fieldwork and guide students in conducting the surveys.

A convenience sample (non-probability sampling procedure) was employed in this study since the researchers did not have access to a census of hotel clients over the age of 18, and it was not possible to determine the probability of any particular element of the population being chosen for the sample [75]. The authors used multistage sampling by quotas, characterizing the population according to two criteria relevant to the investigation: the sex and the age of the respondents [76]. These two variables were selected in order to replicate the Census Bureau (2019) provided to us for a characterization of the population and to provide more objectivity to the analysis. The responder profile statistics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

The authors thoroughly cleansed the data set, looking for missing values and outliers. Any incomplete questionnaires were removed from the sample so that they would not affect the findings of subsequent analyses; nevertheless, this did not have a major impact on the sample distribution in relation to the quotas established during the sampling method. After removing the incorrect questions, we were left with 355 surveys.

The authors looked for discrepancies between early and late responders to investigate the problem of non-response bias [77]. The first 75% of returned questionnaires were considered early replies. The remaining 25% were deemed late respondents and were made up of those who did not reply to the poll. A t-test was used to compare early and late responders for gender, age, education, and occupation, and no significant differences were discovered, indicating that non-response bias was not a problem.

To account for social desirability, bias anonymity and secrecy were vocally reinforced [78]. To further reduce social desirability bias, the authors stressed anonymity and privacy, as well as the fact that there were no right or incorrect responses. Finally, because this study used a single instrument to gather data, common method variance (CMV) may lead to incorrect findings regarding the connections between the suggested variables. This restriction was addressed using Harman’s one-factor approach [79]. For the 18 items manifested in 5 factors, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted (fixed on one factor extraction without any rotations) to determine the total variance of the single factor extracted and estimate whether the total variance of the single factor was below the cut-off value of 50%. The single general factor accounted for 43.26 percent of the total variation accounted for the 18 items, indicating that CMV was not present.

4. Results

To overcome difficulties with non-normality of the data, a covariance-based structural equations model (CB-SEM) method was utilized to evaluate the research hypotheses using a robust maximum-likelihood estimation procedure. To assess the psychometric characteristics of the measurement scales, the measurement model was first calculated using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (reliability and validity). The structural model was then calculated to compare the direct causal effects found in research hypotheses H1 to H5.

4.1. Estimation of the Measurement Model

The results of the goodness-of-fit indices demonstrate that the measurement model is correctly specified. Measures of absolute fit, incremental fit, and parsimonious fit are the three basic types of fit criterion [75]. The metrics used in this case are from EQS 6.1, which is widely used in the SEM literature [77]: Bentler–Bonett normed fit index (BBNFI), Bentler–Bonett non-normed fit index (BBNNFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) for overall model fit; incremental fit index (IFI) and comparative fit index (CFI) for incremental fit; and normed χ2 for model parsimony. Table 2 shows that the BBNFI, BBNNFI, IFI, and CFI statistics all significantly exceed the required minimum value of 0.9. The RMSEA is inside the 0.08 maximum limit, and normed χ2 takes a value that is much below the suggested value of 3.0 [75].

Table 2.

Measurement Model (Confirmatory factor analysis).

The reliability of the measurement scales is evaluated using Cronbach’s Alpha, compound reliability and AVE coefficients [80]. The values of these statistics are, in every case, above or very close to the required minimum values of 0.7 and 0.5 respectively [75], which supports the inner reliability of the proposed constructs (Table 2). The convergent validity of the scales is also confirmed (Table 2), since all items are significant to a confidence level of 95% and their standardized lambda coefficients are higher than 0.5 [81].

Discriminant validity of the scales is tested following the procedure proposed by [82], which is based in the comparison of the variance extracted for each pair of constructs (AVE coefficient) with the squared correlation estimate between these two constructs (see Table 3). If the variances extracted are greater than the squared correlation, this is evidence of discriminant validity. This criterion was fulfilled for every pair of constructs, which supports the discriminant validity of the scales used in this research.

Table 3.

Results for Fornell and Larker’s criterion for discriminant validity.

4.2. Estimation of Hypothesized Structural Model

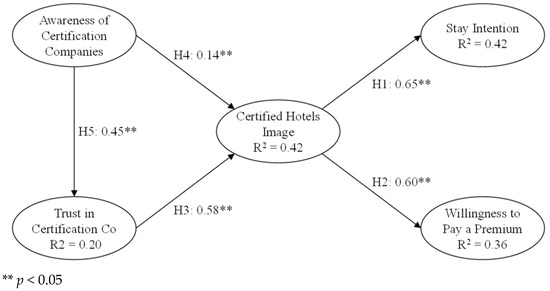

Once the psychometric properties of the scales were adequately examined in the previous stage, the model was estimated using robust maximum likelihood. This method avoids the problems related to non-normality of data by providing the outputs ‘robust chi-square statistic’ and ‘robust standard errors’, which have been corrected for non-normality [83] and, consequently, guarantee the validity of the model estimation. Figure 2 summarizes the results for the estimation of the proposed research model, including R2 statistics for each dependent variable, standardized coefficients for each relationship, and the statistical significance of each effect. The goodness-of-fit indices support the correct definition of the revised model (normed χ2 = 2.9; BBNFI = 0.91; BBNNFI = 0.93; CFI = 0.94; IFI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.07), and R2 statistic take values over o very close to 0.40 for the main dependent variables examined, which shows that the theoretical model proposed provides a substantial explanation of phenomenon under study.

Figure 2.

Structural model (causal effects).

The empirical evidence obtained confirms that the image of quality-certified hotels has a direct and positive influence both on consumers’ intentions to stay at the hotel (hypothesis H1) and their willingness to pay a premium for it (hypothesis H2). Regarding the reputational effect of quality-certification companies, the results summarized in Figure 2 confirm that the image of quality-certified hotels is positively influenced by consumers’ trust in certification companies (hypothesis H3) and their awareness of this type of firm (hypothesis H4). That is to say, the effect provided by the quality-certification on a hotel’s reputation depends on the degree to which consumers perceive certification companies as reliable and renowned. Finally, consumers’ trust on quality-certification companies is positively influenced by their awareness of this type of firm (hypothesis H5), so consumers will perceive as more trustworthy those companies that are more renowned for them.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Tourism is a fundamental pillar of the economy that should confront the challenge of responding to new needs. Currently, tourists are better informed, have new priorities and demand a more customized attention and better quality in services. The hotel industry has components in place to increase competitiveness, such as quality management systems, to help it meet this issue. The most competitive element of a tourist offer that will lead to long-term consumer loyalty is quality [2]. In this regard, client loyalty is the ultimate objective of many businesses, including hotels, because loyal consumers purchase more, spend a higher percentage of their income with the provider, and are less sensitive to price than other customers [84].

Regardless of the fact that existing research in the tourism sector widely addresses loyalty challenges, there is no study in the literature on hotel customer loyalty that investigates the function of quality certifications in conjunction with consumer opinions of certifying bodies. By applying the signaling theory, this study examines the correlation between customer perceptions of certification bodies and the perceived behavior of quality-certified hotels and, through doing so, contributes to the understanding of customer perceptions and behavioral intentions in the context of the consumption of hotel services.

By bringing together diverse research streams, this study adds to the existing research in this field. Internalized consumer perceptions (e.g., recognition and trust of certification bodies) and firm perceptions (e.g., certified image) are combined in this study to explain customer responses to quality-certified hotels. This study proposes a research framework for analyzing customer behavioral intentions toward quality-certified hotels by taking into account customer awareness and trust of certification companies, including the idea that a hotel’s certified image plays a fundamental role in consumer behavior. This study shows that consumer views of certification businesses have a good impact on the image of certified companies, which, in turn, has a positive impact on customer behavioral intentions in terms of staying in a quality, certified hotel and paying a premium for it. Certified hotels can motivate customers to form a mental image of a particular hotel’s level of commitment to quality issues and the way the company presents itself with respect to its performance and service provision by considering quality as a strategic issue, which is consistent with previous research [85]. In this way, the study shows that customer opinions about certification bodies are a key factor in deciding whether or not to stay at a recognized hotel. It has been demonstrated that the level of recognition and trust placed in these institutions and other key hotel service factors play a significant role in influencing customer accommodation decisions, implying that customers recognize the direct benefits of the attributes of a quality-certified hotel. In this regard, our findings are consistent with existing research, which suggests that businesses that are accredited by certification bodies are seen to have a superior application of quality standards, resulting in increased consumer trust [32].

5.2. Managerial Implications

These findings have significant management implications for tourist and hospitality businesses, as well as certification organizations. First, this study demonstrates that in the setting of a certified hotel, a positive hotel image is a powerful instrument for generating favourable customer reactions in terms of desire to stay and readiness to pay a higher price, as previous research suggest [86]. In this regard, hotel management should devise ways to improve public perception of quality-related aspects and establish successful public relations initiatives. Hoteliers, for example, might acquire quality certificates. Several international organizations (for example, AENOR) provide third-party quality certifications, such as ISO 9001, the most widely utilized set of standards for developing a quality management system. Second, hotel managers may use a variety of sources of information to communicate these features, including marketing, public relations campaigns, sponsorships, and social media, because consumer impressions of corporate images can be impacted by communications of this nature. Hotels can develop a favourable image based on quality certification elements by actively participating in specific forums and events, sponsoring quality programs, increasing their social networking reach (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, LinkedIn, etc.) and using in-house advertising (e.g., in-house magazines and television channels aimed at customers).

Third, in light of the importance of customer perceptions of certification companies, these institutions should also emphasize the importance of quality schemes by communicating the advantages of pursuing these certifications and the accolades obtained after their implementation, highlighting their impact on society, not only to corporations (e.g., hotels), but also to customers (e.g., tourists). In addition, hospitality firms should establish specialized programs to educate workers and consumers about certification companies to raise awareness and trust in them. Workers are key mediators in the hotel industry, transmitting information from visitors to management (and vice versa), demonstrating that employees’ awareness of quality concerns is critical to improving the company’s performance. As a result, hoteliers are encouraged to offer quality-related training (e.g., conferences, site visits, contests, etc.) to motivate workers to participate in the hotel’s quality program.

5.3. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

There are several limitations associated with this study. First, the research developed focuses on Spanish tourists, which could restrict the generalizability of the results obtained to other contexts. However, Spain is a leading country in tourism, with a very innovative hotel sector with a wide application of quality schemes, so it can be considered a relevant benchmark to investigate tourists behavior with regard to quality-certified hotels. Another limitation of the research is the use of a convenience sampling procedure. Nevertheless, this potential bias was mitigated by using a multistage sampling by quotas, according to the population of Spanish tourists in terms of gender and age, thus improving the representativeness of the sample. Future studies may focus on additional lodging alternatives (e.g., hostels, guesthouses, self-catered housing, resorts, etc.), nations, or even businesses working in varied business environments (e.g., banking, energy, etc.) to generalize the findings. Additionally, it would be interesting to address other outcomes and antecedents, such as perceived risk, level of involvement, etc. To summarize, this study emphasizes the importance of continuing to investigate the role of certification bodies in tourist behavior in order to increase loyalty in the hospitality context, taking into account the role of awareness and trust in certification companies as antecedents of certified hotels’ image and customers behavioral intentions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.M.G.d.L. and R.G.-L.; methodology, P.M.G.d.L. and A.H.C.; validation and formal analysis, Á.H.C. and J.C.A.; writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, P.M.G.d.L., Á.H.C., R.G.-L. and J.C.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of UNIVERSIDAD DE CANTABRIA (protocol code “CE Trabajo asignatura de Grado 01/2019” and date of approval 16-4-2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Items of the Questionnaire with Their Reference

| Identificator | Item |

| Stay Intention | Adapted from [46] |

| STA1 | I intend to stay in a quality-certified hotel |

| STA2 | I am planning to stay in a quality-certified hotel |

| STA3 | I will make an effort to stay in a quality-certified hotel |

| Willingness to pay a premium | Adapted from [46] |

| PAY1 | It is acceptable to pay more to stay in a quality-certified hotel |

| PAY2 | I am willing to pay more for staying in a quality-certified hotel |

| PAY3 | I am willing to spend more for staying in a quality-certified hotel |

| Certified Hotels Image | Adapted from [72] |

| CHI1 | Services offered by quality-certified hotels are of high quality |

| CHI2 | Services offered by quality-certified hotels have better features that those of than those of non-certified hotel companies |

| CHI4 | Quality-certified hotels transmit a personality that differentiate itself from non-certified hotel companies |

| CHI5 | The hiring of services with quality certified-hotels says something about the kind of person you are |

| CHI6 | I have a picture of the kind of people who contract with quality-certified hotels |

| Trust in certification Companies | Adapted from [73] |

| TCC1 | I believe that quality management systems certification bodies are competent in their activity |

| TCC2 | I believe that quality management systems certification bodies are trustworthy |

| TCC3 | I feel that quality management systems certification bodies are honest when it comes to developing their activities |

| TCC4 | I believe that quality management systems certification bodies are sensitive to consumers’ needs |

| Awareness of Certification Companies | Adapted from [74] |

| ACC1 | Quality management systems certification bodies are clearly recognizable |

| ACC2 | Quality management systems certification bodies are famous among consumers/tourists |

| ACC3 | Quality management systems certification bodies are known to consumers/tourists |

References

- Terlaak, A.; King, A.A. The effect of certification with the ISO 9000 Quality Management Standard: A signaling approach. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2006, 60, 579–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrigos-Simon, F.J.; Narangajavana-Kaosiri, Y.; Narangajavana, Y. Quality in Tourism Literature: A Bibliometric Review. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguí-Amortegui, L.; Clemente-Almendros, J.A.; Medina, R.; Grueso Gala, M. Sustainability and Competitiveness in the Tourism Industry and Tourist Destinations: A Bibliometric Study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slabbert, L.; Du Preez, E. Consumer response towards an accreditation system for hiking trails. World Leis. J. 2017, 59, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Herrera, M.R.; Sasidharan, V.; Álvarez-Hernández, J.A.; Azpeitia-Herrera, L.D. Quality and sustainability of tourism development in Copper Canyon, Mexico: Perceptions of community stakeholders and visitors. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 27, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandampully, J. Service quality to service loyalty: A relationship which goes beyond customer services. Total Qual. Manag. 1998, 9, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnik, G.; Avila, P. Mechanisms to promote continuous improvement in quality management systems. Int. J. Qual. Res. 2015, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Almeida, M.M.; Rodríguez-Antón, J.M.; Rubio-Andrada, L. Reasons for implementing certified quality systems and impact on performance: An analysis of the hotel industry. Serv. Ind. J. 2012, 32, 861–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadesus, M.; Gimenez, G.; Heras, I. Benefits of ISO 9000 implementation in Spanish industry. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2001, 13, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballina, F.J.; Valdés, L.; Del Valle, E. The signaling theory: The key role of quality standards in the hotels performance. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 21, 190–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djofack, S.; Camacho Robledo, M.A. Factors influencing the choice of a quality certification in the Spanish hospitality industry. Qual. Manag. J. 2021, 28, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foris, D.; Popescu, M.; Foris, T. A comprehensive review of the quality approach in tourism. Intech Open Sci. 2018, 10, 159–188. [Google Scholar]

- ISO. The ISO Survey 2020. ISO, 2021. Available online: https://www.iso.org/the-iso-survey.html (accessed on 17 September 2021).

- Djofack, S.; Camacho Robledo, M.A. Implementation of ISO 9001 in the Spanish tourism industry. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2017, 34, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadesus, M.; Marimon, F.; Alonso, M. The future of standardized quality management in tourism: Evidence from the Spanish tourist sector. Serv. Ind. J. 2010, 30, 2457–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Antón, J.M.; Alonso-Almeida, M.M.; Rubio-Andrada, L. Shedding more light on the impacts of quality certified systems in small service enterprises: A multidimensional analysis. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 7911–7922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alonso, M.M.; Barcos, L.; Martin, J.I. Gestión de Calidad de los Procesos Turísticos; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Prajogo, D.; Castka, P. How do external auditors and certification bodies affect firms’ benefits from ISO 9001 certification? In Proceedings of the 15th ANZAM Operations, Supply Chain and Services Management Symposium, Queenstown, New Zealand, 13–14 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, F.; Ryan, C. Analyzing Service Quality in the Hospitality Industry using the SERVQUAL Model. Serv. Ind. J. 1991, 11, 324–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danaher, P.J.; Mattsson, J. Customer Satisfaction during the Service Delivery Process. Eur. J. Mark. 1994, 28, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callan, R.J.; Bowman, L. Selecting a hotel and determining salient quality attributes: A preliminary study of mature british travellers. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2000, 2, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callan, R.J.; Kyndt, J. Business Travellers’ Perception of Service Quality: A Prefatory Study of Two European City Centre Hotels. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2001, 3, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.; Min, H.; Chung, K. Dynamic benchmarking of hotel service quality. J. Serv. Mark. 2002, 16, 302–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, C.; Wei, Y. Social Media Peer Communication and Impacts on Purchase Intentions: A Consumer Socialization Framework. J. Interact. Mark. 2012, 26, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez García de Leaniz, P.; Herrero Crespo, A.; Gómez López, R. Customer responses to environmentally certified hotels: The moderating effect of environmental consciousness on the formation of behavioral intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1160–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Perlines, F.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Han, H.; Law, R. Innovative capacity, quality certification and performance in the hotel sector. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 82, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Almeida, M.M.; Marimon, F.; Bernardo, M. Diffusion of quality standards in the hospitality sector. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2013, 33, 504–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peach, R. The ISO 9000 Handbook; QSU Publishing Company: Fairfax, VA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Castka, P. Audit and Certification: What do Users Expect? Joint Accreditation System of Australia and New Zealand: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rametsteiner, E.; Simula, M. Forest certification: An instrument to promote sustainable forest management? J. Environ. Manag. 2003, 67, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, I.; Husted, B.W.; Christmann, P. Using private management standard certification to reduce information asymmetries in corrupt environments. Strategic Manag. J. 2013, 33, 1103–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajogo, D.; Nair, A.; Castka, P. The effects of external auditors and certification bodies on the operational and market-oriented outcomes of ISO 9001 implementation. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2020, 99, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.L. Quality differentiation and condition al special price competition among hotels. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durna, U.; Dedeoglu, B.B.; Balikcioglu, S. The role of servicescape and image perceptions of customers on behavioral intentions in the hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1728–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, E.; Jang, S.; Day, J.; Ha, S. The impact of eco-friendly practices on green image and customer attitudes: An investigation in a cafe setting. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 41, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Hsu, L.T.; Han, H.; Kim, Y. Understanding how consumers view green hotels: How a hotel’s green image can influence behavioural intentions. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 901–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Lee, H.R.; Kim, W.G. The influence of the quality of the physical environment, food, and service on restaurant image, customer perceived value, customer satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 24, 200–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Bitter, M.J. Services Marketing; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P. Marketing Management: Analysis Planning Implementation and Control; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Karaosmanoglu, E.; Melewar, T.C. Corporate communications, identity and image: A research agenda. J. Brand. Manag. 2006, 14, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J. Corporate image effects on consumers’ evaluation of brand trust and brand affect. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2007, 17, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, G.R. Creating Corporate Reputation; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Assael, H. Consumer Behavior and Marketing Action; Kent Publishing: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.; Lee, J. Empirical investigation of the roles of attitudes toward green behaviors, overall image, gender, and age in hotel customers’ eco-friendly decision-making process. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2009, 28, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Mattila, A.; Lee, S. A meta-analysis of behavioral intentions for environment-friendly initiatives in hospitality research. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 54, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Yang, S.U. Comparing effects of country reputation and the overall corporate reputations of a country on international consumers’ product attitudes and purchase intentions. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2010, 13, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, E.; Hwang, Y.K.; Kim, E.Y. Green marketing’ functions in building corporate image in the retail setting. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1709–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavian, C.; Guinaliu, M.; Torres, E. The influence of corporate image on consumer trust: A comparative analysis in traditional versus internet banking. Internet Res. 2005, 15, 447–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artigas, E.M.; Yrigoyen, C.C.; Moraga, E.T. Determinants of Trust towards Tourist Destinations. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 327–334. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Xiang, Z.; Fesenmaier, D.R. Smartphone Use in Everyday Life and Travel. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindskold, S. Trust development, the grit proposal and the effects of conciliatory acts on conflict and cooperation. Psychol. Bull. 1978, 85, 772–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.M.; Hunt, S.D. The commitment- trust theory of relationship marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homburg, C.; Kuester, S.; Beutin, N.; Menon, A. Determinants of customer benefits in business- to-business markets: A cross-cultural comparison. J. Int. Mark. 2005, 13, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, P.R.; Miller, E.; Pearce, A.R.; Meyer, S.B. Predictors and Extent of Institutional Trust in Government, Banks, the Media and Religious Organizations: Evidence from Cross-Sectional Surveys in Six Asia-Pacific Countries. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotter, J.B. A New Scale for the Measurement of Interpersonal Trust. J. Personal. 1967, 35, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chocarro, R.; Cortiñas, M.; Elorz, M. The impact of product category knowledge on consumer use of extrinsic cues. A study involving agrifood products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2009, 20, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo, Y.; Cambra, J. Influence of the standardization of a firm’s productive process on the long-term orientation of its supply relationships: An empirical study. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2008, 37, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewally, M.; Ederington, L. Reputation, certification, warranties, and information as remedies for seller-buyer information asymmetries. J. Bus. 2006, 79, 693–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durcikova, A.; Gray, P. How knowledge validation processes affect knowledge contribution. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2009, 25, 81–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busenitz, L.W.; Fiet, J.O.; Moesel, D.D. Signaling in venture capitalist–new venture team funding decisions: Does it indicate long-term venture outcomes? Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, B.L.; Certo, S.T.; Ireland, R.D.; Reutzel, C.R. Signaling theory: A review and assessment. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Building Strong Brands; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer, W.D.; Brown, S.P. Effects of brand awareness on choice for a common, repeat purchase product. J. Consum. Res. 1990, 17, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreda, A.A.; Bilgihan, A.; Nusair, K.; Okumus, F. Generating brand awareness in online social networks. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 50, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring, and Managing Brand Equity, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cordell, V.V. Consumer knowledge measures as predictors in product evaluation. Psychol. Mark. 1997, 14, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, T.; Swait, J. Brand equity as a signaling phenomenon. J. Consum. Psychol. 1998, 7, 131–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, N.; Noor, N.; Mohamad, O. Does image of country-of-origin matter to brand equity? J. Prod. Brand. Manag. 2007, 16, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.R. The Architecture of Cognition; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. Trust and Power; Wiley: Chester, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, E.; Montaner, T.; Pina, J.M. Propuesta de una metodología. Medición de la imagen de marca. Un estudio exploratorio. ESIC Mark. 2004, 117, 199–216. [Google Scholar]

- Sirdeshmukh, D.; Singh, J.; Sabol, B. Customer trust, value, and loyalty in relational exchanges. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 15–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, H.; San Martín, H.; Garcia de los Salmones, M.M.; Collado, J. Examining the hierarchy of destination brands and the chain of effects between brand equity dimensions. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística: Padrón. Población por Municipios. Available online: www.ine.es (accessed on 16 April 2019).

- Armstrong, J.S.; Overton, T.S. Estimating non-response bias in mail surveys. J. Mark. Res. 1977, 14, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Monroe, G.S. Exploring Social Desirability Bias. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, J.B.E.; Van Trijp, H. The Use of LISREL in Validating Marketing Constructs. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1991, 8, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modelling with EQS and EQS/Windows: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, P.; Naumann, E. Customer satisfaction and business performance: A firm-level analysis. J. Serv. Mark. 2011, 25, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandampully, J.; Devi, T.; Hu, H.H. The influence of a hotel firm’s quality of service and image and its effect on tourism customer loyalty. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2011, 12, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Herrero, A.; Gómez-López, R. The role of environmental CSR practices on the formation of behavioral intentions in a certified hotel context. Span. J. Mark. -ESIC 2019, 23, 205–226. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).