A Systematic Review of Effective Instructional Interventions in Supporting Kindergarten English Learners’ English Oral Language Development

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Kindergarten ELs’ Oral Language Development

1.2. Definition of ELs and Types of Bilingual Program

- What are the characteristics of the EL students involved in the studies (i.e., native language, location, SES background)?

- What bilingual program types were used in these studies?

- What was the impact of instructional intervention on kindergarten ELs’ oral language development?

- What instruments were applied to measure ELs’ English oral language proficiency?

2. Method

2.1. Selection Criteria

- Research participants included ELs in kindergarten;

- Research outcomes of the study included English oral language development;

- Research involved an intervention that was aimed at improving the quality of instruction, which led to oral language development;

- Intervention studies included pre- and post-assessment;

- Research was conducted in the United States;

- Studies were peer-reviewed quantitative studies.

- Studies using kindergarten students’ oral language outcome as a baseline or predictor of later reading or writing performance, which meant there was no report on their performance at the kindergarten year independently;

- Studies including outcomes other than the six components of oral language proficiency outlined by Fisher and Frey [2];

- Studies conducted to analyze the psychometrician characteristic of an instrument designed to measure oral language development of kindergarten ELs;

- Studies conducted in other English-speaking countries with ELs;

- Master’s theses and doctoral dissertations.

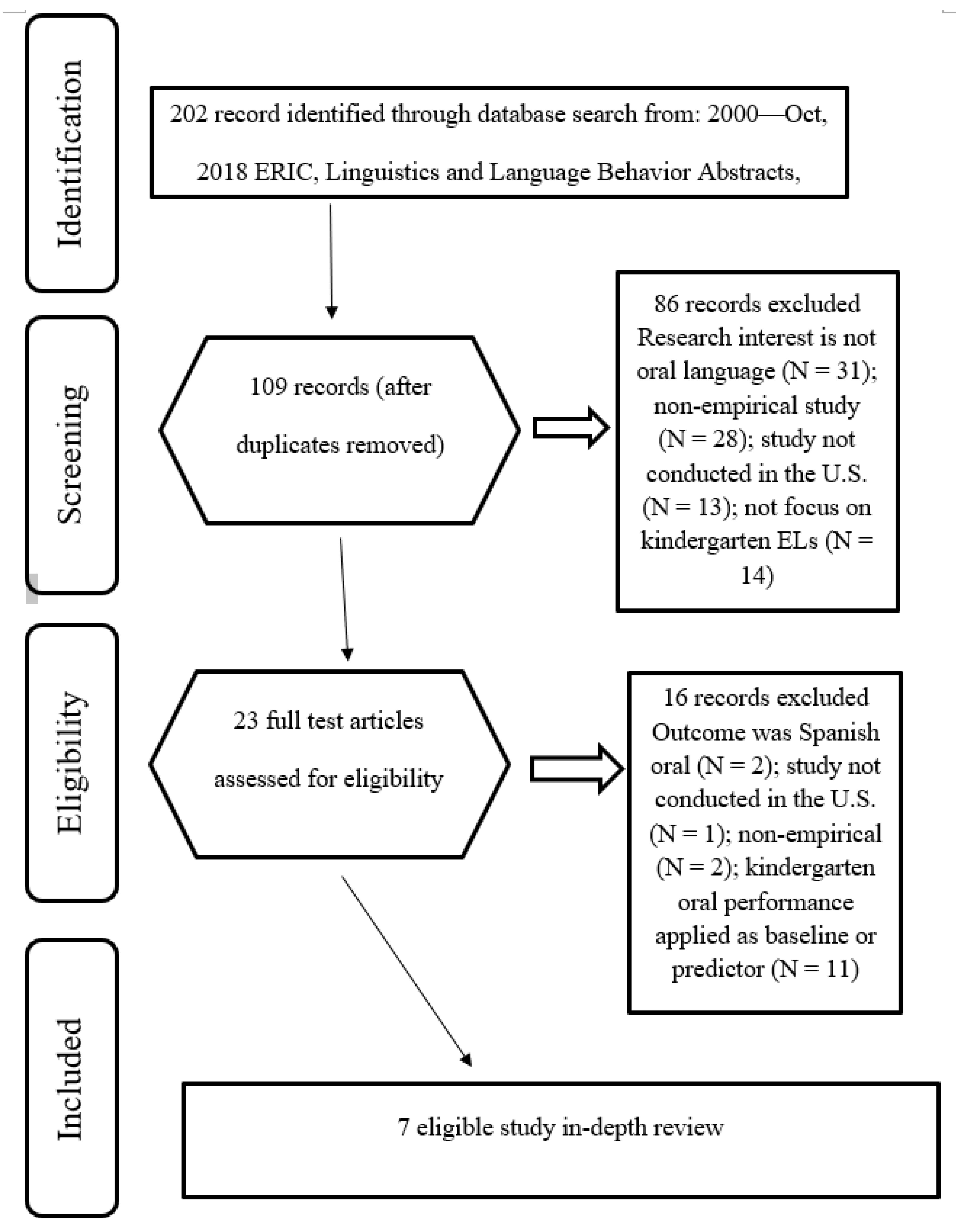

2.2. Location and Selection of Studies

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Program Types

3.3. Intervention

3.3.1. Language-Based Intervention

3.3.2. Oral Vocabulary Intervention

3.3.3. English Language and Literacy Acquisition (ELLA)

3.3.4. Whole-School Interventions

3.4. Measurement

Researcher-Developed Instrument

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Limitation

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Center for Education Statistics. The Condition of Education 2020; U.S. Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Fisher, D.; Frey, N. Developing oral language skills in middle school English learners. Read. Writ. Quart. 2018, 34, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, L.; Markman-Pithers, L. Supporting young English learners in the United States. Future Child. 2016, 26, 159–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanzenbach, D.W.; Bauer, L.; Mumford, M. Lessons for broadening school accountability under the Every Student Succeeds Act. Hamilt. Proj. Brook. Inst. 2016, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.; Yan, D.; Song, M. Literacy planning: Family language policy in Chinese kindergartener families. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlisle, J.F.; Beeman, M.; Davis, L.H.; Spharim, G. Relationship of metalinguistic capabilities and reading achievement for children who are becoming bilingual. Appl. Psycholinguist. 1999, 20, 459–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manis, F.R.; Lindsey, K.A.; Bailey, C.E. Development of reading in grades K–2 in Spanish-speaking English-language learners. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 2004, 19, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.F.; Heilmann, J.; Nockerts, A.; Iglesias, A.; Fabiano, L.; Francis, D.J. Oral language and reading in bilingual children. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 2006, 21, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, N.; Kibler, A. Oral English language proficiency and reading mastery: The role of home language and school supports. J. Educ. Res. 2016, 109, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, C.P.; August, D.; Carlo, M.S.; Snow, C. The intriguing role of Spanish language vocabulary knowledge in predicting English reading comprehension. J. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 98, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Swanson, H.L.; Rosston, K.; Gerber, M.; Solari, E. Influence of oral language and phonological awareness on children’s bilingual reading. J. Sch. Psychol. 2008, 46, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yesil-Dagli, U. Predicting ELL students’ beginning first grade English oral reading fluency from initial kindergarten vocabulary, letter naming, and phonological awareness skills. Early Child. Res. Quart. 2011, 26, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- August, D.; Shanahan, T. Developing Literacy in Second Language Learners: Report of the National Literacy Panel on Minority-Language Children and Youth; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fernald, A.; Weisleder, A. Early language experience is vital to developing fluency in understanding. Handb. Early Lit. Res. 2011, 3, 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Genesee, F. Rethinking Early Childhood Education for English Language Learners: The Role of Language. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Sally-Dixon-2/publication/319273616_Making_the_ESL_classroom_visible_Indigenous_Australian_children’s_early_education/links/599fde900f7e9b363906e3e1/Making-the-ESL-classroom-visible-Indigenous-Australian-childrens-early-education.pdf#page=12 (accessed on 2 February 2019).

- Genesee, F.; Lindholm-Leary, K.; Saunders, W.; Christian, D. English language learners in US schools: An overview of research findings. J. Educ. Stud. Placed Risk 2005, 10, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, K.M.; Khaksari, M.; Eng, L.S.; Ghani, A.M.A. The role of learner-learner interaction in the development of speaking skills. Theory Pract. Lang. Stud. 2016, 6, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saunders, W.; O’Brien, G. Oral language. In Educating English Language Learners: A Synthesis of Research Evidence; Genesee, F., Lindholm-Leary, K., Christian, D., Saunders, B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 14–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kieffer, M.J. Early oral language and later reading development in Spanish-speaking English language learners: Evidence from a nine-year longitudinal study. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 33, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, D.J.; Rivera, M.; Lesaux, N.; Kieffer, M.; Rivera, H. Practical Guidelines for the Education of English Language Learners: Research-Based Recommendations for Instruction and Academic Interventions; RMC Research, Center on Instruction: Portsmouth, NH, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Turkan, S.; De Oliveira, L.C.; Lee, O.; Phelps, G. Proposing a knowledge base for teaching academic content to English language learners: Disciplinary linguistic knowledge. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2014, 116, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, J.E.; Uhing, B.M. Home literacy environments and young Hispanic children’s English and Spanish oral language: A communality analysis. J. Early Interv. 2008, 30, 116–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, D.K.; Tabors, P.O. Beginning Literacy with Language: Young Children Learning at Home and School; Brookes: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, M.; Lambert, R.; Abbott–Shim, M.; McCarty, F.; Franze, S. A model of home learning environment and social risk factors in relation to children’s emergent literacy and social outcomes. Early Child. Res. Quart. 2005, 20, 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, M.M.; Acock, A.C.; Morrison, F.J. The impact of kindergarten learning-related skills on academic trajectories at the end of elementary school. Early Child. Res. Quart. 2006, 21, 471–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ray, K.; Smith, M.C. The kindergarten child: What teachers and administrators need to know to promote academic success in all children. Early Child. Educ. J. 2010, 38, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulting, A.B.; Malone, P.S.; Dodge, K.A. The effect of school-based kindergarten transition policies and practices on child academic outcomes. Dev. Psychol. 2005, 41, 860–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Farnsworth, M. Who’s coming to my party? Peer talk as a bridge to oral language proficiency. Anthropol. Educ. Quart. 2012, 43, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, C.; Pilonieta, P. Using interactive writing instruction with kindergarten and first-grade English language learners. Early Child. Educ. J. 2012, 40, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M. My name is Maria: Supporting English language learners in the kindergarten general music classroom. Gen. Music Today 2011, 24, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero, A. Oral narrative retelling among emergent bilinguals in a dual language immersion program. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2018, 21, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. The Effects of Integrated Language-Based Instruction in Elementary ESL Learning. Mod. Lang. J. 2008, 92, 431–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spycher, P. Learning academic language through science in two linguistically diverse kindergarten classes. Elem. Sch. J. 2009, 109, 359–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, F.; Lara-Alecio, R.; Irby, B.; Mathes, P.; Kwok, O.M. Accelerating early academic oral English development in transitional bilingual and structured English immersion programs. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2008, 45, 1011–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, A.C.; Slavin, R.E. Effective reading programs for Spanish-dominant English language learners (ELLs) in the elementary grades: A synthesis of research. Rev. Educ. Res. 2012, 82, 351–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rolstad, K.; Mahoney, K.; Glass, G.V. The big picture: A meta-analysis of program effectiveness research on English language learners. Educ. Policy 2005, 19, 572–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slavin, R.E.; Cheung, A. A synthesis of research on language of reading instruction for English language learners. Rev. Educ. Res. 2005, 75, 247–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marulis, L.M.; Neuman, S.B. The effects of vocabulary intervention on young children’s word learning: A meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2010, 80, 300–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bardack, S. Common ELL Terms and Definitions; American Institutes for Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. Our Nation’s English Learners. 2018. Available online: https://www2.ed.gov/datastory/el-characteristics/index.html#four (accessed on 16 July 2019).

- Lara-Alecio, R.; Galloway, M.; Irby, B.J.; Rodríguez, L.; Gómez, L. Two-way immersion bilingual programs in Texas. Biling. Res. J. 2004, 28, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphey, A.F. The effect of dual-language and transitional-bilingual education instructional models on Spanish proficiency for English language learners. Biling. Res. J. 2014, 37, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, L.; Freeman, D.; Freeman, Y. Dual language education: A promising 50–50 model. Biling. Res. J. 2005, 29, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholm-Leary, K. Bilingualism and academic achievement in children in dual language programs. In Bilingualism Across the Lifespan: Factors Moderating Language Proficiency; De Gruyter Mouton: Berlin, German, 2016; pp. 203–223. [Google Scholar]

- Gough, D.; Oliver, S.; Thomas, J. Introducing Systematic Reviews; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Int. J. Surg. 2010, 8, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cooper, H.; Hedges, L.V.; Valentine, J.C. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis, 2nd ed.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, I.D.; Crum, J.A. New activities and changing roles of health sciences librarians: A systematic review, 1990–2012. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2013, 101, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmagarmid, A.; Ilyas, I.F.; Ouzzani, M.; Quiané-Ruiz, J.A.; Tang, N.; Yin, S. NADEEF/ER: Generic and interactive entity resolution. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, Snowbird, UT, USA, 22–27 June 2014; pp. 1071–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, R.D. Vocabulary development of English-language and English-only learners in kindergarten. Elem. Sch. J. 2007, 107, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, F.; Irby, B.J.; Lara-Alecio, R.; Yoon, M.; Mathes, P.G. Hispanic English learners’ responses to longitudinal English instructional intervention and the effect of gender: A multilevel analysis. Elem. Sch. J. 2010, 110, 542–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, W.M.; Foorman, B.R.; Carlson, C.D. Is a separate block of time for oral English language development in programs for English learners needed? Elem. Sch. J. 2006, 107, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, F.; Irby, B.J.; Lara-Alecio, R.; Mathes, P.G. English and Spanish acquisition by Hispanic second graders in developmental bilingual programs: A 3-year longitudinal randomized study. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2008, 30, 500–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, I.L.; McKeown, M.G.; Kucan, L. Bringing Words to Life: Robust Vocabulary Instruction; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Irby, B.J.; Lara-Alecio, R.; Quiros, A.M.; Mathes, P.G.; Rodriguez, L. English Language and Literacy Acquisition Evaluation Research Program (Project ELLA): Second Annual Evaluation Report; U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Educational Sciences: Washington, DC, USA, 2004.

- Ventriglia, L.; Gonzalez, L. Santillana Intensive English; Santillana: Miami, FL, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Teale, W.; Martinez, M. Teacher story book reading style: A comparison of six teachers. Res. Teach. Engl. 1993, 27, 175–199. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson, D.; Smith, M.K. Long-term effects of preschool teachers’ book reading on low-income children’s vocabulary and story comprehension. Read. Res. Quart. 1994, 29, 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, I.; McKeown, M. Text Talk: Capturing the benefits of read-aloud experiences for young children. Read. Teach. 2001, 55, 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Juel, C.; Biancarosa, G.; Coker, D.; Deffes, R. Walking with Rosie: A cautionary tale of early reading instruction. Educ. Leadersh. 2003, 60, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock, R.W. Woodcock Language Proficiency Battery-Revised: English and Spanish Forms: Examiner’s Manual; Riverside Publishing: Rolling Meadows, IL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock, R.W.; Muñoz-Sandoval, A.F. Woodcock-Muñoz Language Survey, English Form; Riverside Publishing: Rolling Meadows, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer, P.; Hammill, D. Test of Language Development—Primary; Pro-Ed: Austin, TX, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, L.M.; Dunn, L.M. Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test–III. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 1998, 16, 334–338. [Google Scholar]

- Immunex Corporation. Defining Moments: Enliven 2002; Wyeth-Ayerst Pharmaceutical and Immunex: Seattle, WA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, K.R. The Oxford Picture Dictionary for Kids; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton, J.B. Composition Through Pictures; Longman: London, UK, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, L.R.; Krach, S.K.; McCreery, M.P.; Navarro, S. The student oral language observation matrix: A psychometric study with preschoolers. Assess. Eff. Interv. 2018, 45, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendeou, P.; Van den Broek, P.; White, M.J.; Lynch, J.S. Predicting reading comprehension in early elementary school: The independent contributions of oral language and decoding skills. J. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 101, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pullen, P.C.; Justice, L.M. Enhancing phonological awareness, print awareness, and oral language skills in preschool children. Interv. Sch. Clin. 2003, 39, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spira, E.G.; Bracken, S.S.; Fischel, J.E. Predicting improvement after first-grade reading difficulties: The effects of oral language, emergent literacy, and behavior skills. Dev. Psychol. 2005, 41, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, F.; Luo, W.; Irby, B.J.; Lara-Alecio, R.; Rivera, H. Investigating the impact of professional development on teachers’ instructional time and English learners’ language development: A multilevel cross-classified approach. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 2017, 20, 292–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redford, J. English Language Program Participation among Students in the Kindergarten Class of 2010-11: Spring 2011 to Spring 2012. Stats in Brief. NCES 2018-086; National Center for Education Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Boyle, A.; August, D.; Tabaku, S.; Cole, S.; Simpson-Baird, A. Dual Language Education Programs: Current State Policies and Practices, 2015. Office of English Language Acquisition, U.S. Department of Education. Available online: https://ncela.ed.gov/files/rcd/TO20_DualLanguageRpt_508.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2020).

- Texas Education Agency. Bilingual and English as a Second Language Education Programs. 2021. Available online: https://statutes.capitol.texas.gov/Docs/ED/htm/ED.29.htm#B (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Ball, J. Educational Equity for Children from Diverse Language Backgrounds: Mother Tongue-Based Bilingual or Multilingual Education in the Early Years: Summary. Available online: http://dspace.library.uvic.ca/bitstream/handle/1828/2457/UNESCO%20Summary%202010.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Lindholm-Leary, K.; Genesee, F. Student outcomes in one-way, two-way, and indigenous language immersion education. J. Immers. Content-Based Lang. Educ. 2014, 2, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Alecio, R.; Tong, F.; Irby, B.J.; Mathes, P. Teachers’ pedagogical differences during ESL block among bilingual and English-immersion kindergarten classrooms in a randomized trial study. Biling. Res. J. 2009, 32, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, O.; Buxton, C.A. Teacher professional development to improve science and literacy achievement of English language learners. Theory Pract. 2013, 52, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, F.; Irby, B.J.; Lara-Alecio, R.; Guerrero, C.; Tang, S. The impact of professional learning on in-service teachers’ pedagogical delivery of literacy-infused science with middle school English learners: A randomized controlled trial study in the U.S. Educ. Stud. 2018, 45, 533–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Education for All Global Monitoring Report: Education for All 2000–2015–Achievements and Challenges; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2015.

| Author | Journal | Title |

|---|---|---|

| Rebecca Silverman | The Elementary School Journal | A Comparison of Three Methods of Vocabulary Instruction during Read-Alouds in Kindergarten |

| Fuhui Tong, Rafael Lara-Alecio, Beverly Irby, Patricia Mathes, and Oi-man Kwok | American Educational Research Journal | Accelerating Early Academic Oral English Development in Transitional Bilingual and Structured English Immersion Programs |

| Fuhui Tong, Beverly Irby, Rafael Lara-Alecio, and Patricia Mathes | Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences | English and Spanish Acquisition by Hispanic Second Graders in Developmental Bilingual Programs: A Three-Year Longitudinal Randomized Study |

| Fuhui Tong, Beverly Irby, Rafael Lara-Alecio, Myeongsun Yoon, and Patricia Mathes | The Elementary School Journal | Hispanic English Learners’ Responses to Longitudinal English Instructional Intervention and the Effect of Gender: A Multilevel Analysis |

| Saunders William, Barbara Foorman, and Coleen Carlson | The Elementary School Journal | Is a Separate Block of Time for Oral English Language Development in Programs for English Learners Needed? |

| Pamela Spycher | The Elementary School Journal | Learning Academic Language through Science in Two Linguistically Diverse Kindergarten Classes |

| Youb Kim | The Modern Language Journal | The Effects of Integrated Language-Based Instruction in Elementary ESL Learning |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z. A Systematic Review of Effective Instructional Interventions in Supporting Kindergarten English Learners’ English Oral Language Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12477. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212477

Wang Z. A Systematic Review of Effective Instructional Interventions in Supporting Kindergarten English Learners’ English Oral Language Development. Sustainability. 2021; 13(22):12477. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212477

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhuoying. 2021. "A Systematic Review of Effective Instructional Interventions in Supporting Kindergarten English Learners’ English Oral Language Development" Sustainability 13, no. 22: 12477. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212477

APA StyleWang, Z. (2021). A Systematic Review of Effective Instructional Interventions in Supporting Kindergarten English Learners’ English Oral Language Development. Sustainability, 13(22), 12477. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212477