Human Resource Management in Crisis Situations: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Different Crises and HRM

2.1.1. Economic Crisis and HRM

2.1.2. Other Kind of Crisis and HRM

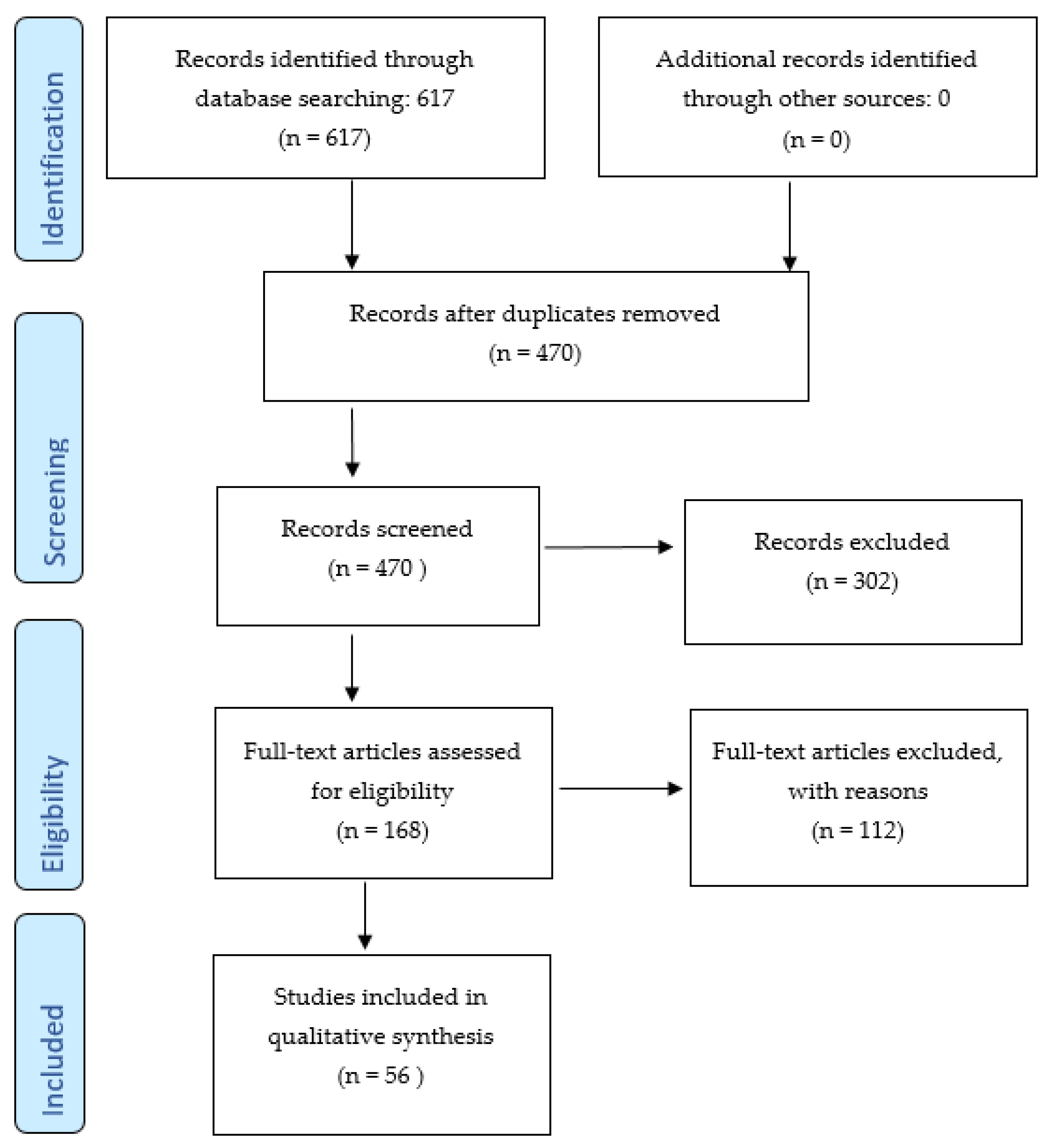

3. Methods of the Literature Review

4. Results

4.1. General Observations

4.2. Research Methods Applied in the Papers

4.3. Themes

4.3.1. Economic Crisis and HRM

4.3.2. Health Crisis and HRM

4.3.3. Natural Disasters and HRM

4.3.4. Political Instability and HRM

4.3.5. Different Types of Crises and HRM

5. Discussion

- Some studies [46,47] have shown that economic recessions tend to harm gender equality, such as hiring educated women, rising wage inequality, etc. The limited number of papers on this topic indicates not only a need for further research but also awareness-raising activities to reduce the danger that positive developments regarding gender equality are not only come to a standstill but in a worst-case scenario are even reversed.

- Only one paper [43] was identified that did address the different paths that small and large firms take to deal with an economic crisis. Given the impact of heterogeneity on organisations and their capabilities with regard to HRM as well as the role of smaller firms in economies, there is an urgent need for more fine-grained research that takes into account size differences.

- Furthermore, only one paper [40] was found that focused on the outsourcing of HRM in the wake of economic recession. Given the emphasis on the hard approach to HRM in times of economic crisis, there is a need for more research on utilising outsourcing as an HRM practice in those times.

- The papers in the review solely focused on the demand side of economic shocks and their impact on HRM. There is, therefore, a need for an analysis of supply-side economic shocks, such as oil price turmoil in the last decade. There is also a need for research on governments’ policy responses and their implication for public–private coordination.

- Most of the papers on COVID-19 focused on the health care and hospitality and tourism industries. What has happened in other industries is unknown but needs research as well.

- As already noted, COVID-19, like other crises, has posed many challenges to the persons in charge of HRM in organisations, such as the need for rapid and decisive responses as well as the use of new communication channels and other forms of communication [30]. At the same time, it was noted that so far only very few papers have dealt with these challenges; they were found in the areas of health, i.e., challenges faced by nurse managers [61] and tourism [22,67]. More research is needed on the specific challenges of health crises and their implications for HR managers and their activities.

- Based on the review, the papers that investigated COVID-19 mostly addressed issues like fears, burnout, and other physical and psychological factors. Only one paper [29] was identified that investigated remote working, showing that organisational values and job motivation can enhance organisational commitment during remote working. No papers were found on the work–life balance or quality of life of the persons in remote working. That is surprising, given that millions of people have been working remotely in the last two years. How has social isolation affected people in remote working? Has burnout increased or decreased? How have organisations provided work equipment for employees to work at home? Have family conflicts increased during the pandemic due to remote working? How has the relationship between employees and HRM managers changed due to remote working?

- It was also found that no paper dealt with changes in labour markets or employment relations as a consequence of the pandemic. It seems it is time to start with more research in these areas. Given that the pandemic is still ongoing, the opportunity to do longitudinal research is still there. How many companies laid off employees or put staff in part-time jobs? Has outsourcing increased during the pandemic? Have general labour agreements between employees and organisations been changed due to the pandemic? Tourism was very badly hit around the world due to the pandemic, with the closure or downsizing of many companies. Is there a difference in labour market changes between industries? Did public organisations maintain their employment relations with employees to a greater extent than private companies? Have smaller firms worked more intensively on maintaining the relationships with their staff than larger firms?

- Nations around the world imposed different restrictions to prevent the spread of COVID-19, with few restrictions in the beginning (US, Britain) or hard lockdowns (Australia, New Zealand), and with some countries choosing a middle road with quarantine and social distancing (Iceland). It would be of interest to analyse how these divergent policies have affected HRM practices in different countries, e.g., HR-related approaches to address the well-being of employees. It would be expected that in countries with hard lockdowns, firms and employees experienced more immediate effects regarding distance work, employment relations, and social isolation compared to firms and employees in countries with few restrictions.

- A recent Australian study demonstrated that COVID-19 has had a positive effect on employees, such as more family time, increased work flexibility, and a calmer life [74]. There has also been a vast advancement in online education, as well as in remote working tools and online meetings (Zoom, Teams, etc.). Further research should focus on the potential positive effects of the pandemic on HRM in organisations. In addition, are they found in all companies or sectors, or only in certain ones? Moreover, if so, why is that so?

- One study [68] showed that a health crisis changed the priorities in the life and motivation of employees in the financial sector in Spain. Is that the case in other sectors and other countries as well? In addition, what do these changed priorities mean for HRM in organisations?

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barney, J. Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management? Yes. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Klaas, B.S. Outsourcing and the HR function: An examination of trends and developments within North American firms. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 19, 1500–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang-Richards, Y.; Wilkinson, S.; Seville, E.; Brunsdon, D. Effects of a major disaster on skills shortages in the construction industry. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2017, 24, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ererdi, C.; Nurgabdeshov, A.; Kozhakhmet, S.; Rofcanin, Y.; Demirbag, M. International HRM in the context of uncertainty and crisis: A systematic review of literature (2000–2018). Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beardwell, J.; Clark, I. An Introduction to Human Resource Management. In Human Resource Management: A Contempory Approach, 6th ed.; Beardwell, J., Claydon, T., Eds.; Pearson: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Edvardsson, I.R.; Óskarsson, G.K. Outsourcing of Human Resources: The Case of Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises. Merits 2021, 1, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cater, J.J.; Beal, B. Ripple effects on family firms from an externally induced crisis. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2014, 4, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doern, R.; Williams, N.; Vorley, T. Special issue on entrepreneurship and crises: Business as usual? An introduction and review of the literature. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2019, 31, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.A.; Woods, C.L.; Staricek, N.C. Restorative rhetoric and social media: An examination of the Boston Marathon bombing. Commun. Stud. 2017, 68, 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Crisis Management. Annual ICM Crisis Report: News Coverage of Business Crises During 2003; Institute for Crisis Management: Louisville, KY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel, M.; Stanske, S.; Lieberman, M.B. Strategic responses to crisis. Strat. Manag. J. 2020, 41, V7–V18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abberger, K.; Nierhaus, W. How to Define a Recession? Cesifo Forum 2008, 9, 74–76. [Google Scholar]

- Santana, M.; Cabrera, R.V.; Gonzalez, J.-L.G. Sources of decline, turnaround strategy and HR strategies and practices: The case of Iberia Airlines. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2018, 40, 583–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, C. Turnaround Strategy. J. Bus. Strategy 1980, 1, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnigle, P.; Lavelle, J.; Monaghan, S. Weathering the storm? Multinational companies and human resource management through the global financial crisis. Int. J. Manpow. 2013, 34, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Johnstone, S. Employment practices, labour flexibility and the Great Recession: An automotive case study. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2018, 40, 537–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagelmeyer, S.; Heckmann, M.; Kettner, A. Management responses to the global financial crisis in Germany: Adjustment mechanisms at establishment level. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 3355–3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.; Lee, K.-Y.; Lee, J. Dismissal law and human resource management in SMEs: Lessons from Korea. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2011, 49, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adikaram, A.S.; Naotunna, N.; Priyankara, H. Battling COVID-19 with human resource management bundling. Empl. Relat. 2021, 43, 1269–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, M. Investing in management development in turbulent times and perceived organisational performance: A study of UK MNCs and their subsidiaries. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 2491–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; D’Netto, B. Impact of the 2007–09 global economic crisis on human resource management among Chinese export-oriented enterprises. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2012, 18, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Chang-Richards, A.Y.; Kleinsman, T.; Innes, A. Improving human resource mobilisation for post-disaster recovery: A New Zealand case study. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 52, 101998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlot, E.S.; De Cieri, H. The challenges of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami for strategic international human resource management in multinational nonprofit enterprises. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 1303–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durst, S.; Palacios Acuache, M.M.G.; Bruns, G. Peruvian small and medium-sized enterprises and COVID-19: Time for a new start! J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2021, 13, 648–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collings, D.G.; Nyberg, A.J.; Wright, P.M.; McMackin, J. Leading through paradox in a COVID-19 world: Human resources comes of age. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, F.; Almaghthawi, A.; Katib, I.; Albeshri, A.; Mehmood, R. iResponse: An AI and IoT-Enabled Framework for Autonomous COVID-19 Pandemic Management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Tan, F.P.L. Nurses’ experiences in response to COVID-19 in a psychiatric ward in Singapore. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2021, 68, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radic, A.; Lück, M.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Han, H. Fear and Trembling of Cruise Ship Employees: Psychological Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanpipat, W.; Lim, H.; Deng, X. Implementing Remote Working Policy in Corporate Offices in Thailand: Strategic Facility Management Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, K.; Nguyen, P.T.; Bouckenooghe, D.; Rafferty, A.; Schwarz, G. Unraveling the What and How of Organizational Communication to Employees during COVID-19 Pandemic: Adopting an Attributional Lens. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2020, 56, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fee, A.; McGrath-Champ, S.; Berti, M. Protecting expatriates in hostile environments: Institutional forces influencing the safety and security practices of internationally active organisations. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 30, 1709–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkeland, M.S.; Hansen, M.B.; Blix, I.; Solberg, Ø.; Heir, T. For Whom Does Time Heal Wounds? Individual Differences in Stability and Change in Posttraumatic Stress After the 2011 Oslo Bombing. J. Traum. Stress 2017, 30, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesson, J.; Matheson, L.; Lacey, F. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, L. Thematic coding and analysis. Sage Encycl. Qual. Res. Methods 2008, 1, 876–878. [Google Scholar]

- Aoki, K.; Delbridge, R.; Endo, T. ‘Japanese human resource management’ in post-bubble Japan. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 25, 2551–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-I. Study on human resource management in Korea’s chaebol enterprise: A case study of Samsung Electronics. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 1436–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, H.; MacKenzie, R.; Forde, C. HRM and performance: The vulnerability of soft HRM practices during recession and retrenchment. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2016, 26, 557–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edvardsson, I.R.; Teitsdóttir, U.D. Outsourcing and financial crisis: Evidence from Icelandic service SMEs. Empl. Relat. 2015, 37, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmendia, A.; Elorza, U.; Aritzeta, A.; Madinabeitia-Olabarria, D. High-involvement HRM, job satisfaction and productivity: A two wave longitudinal study of a Spanish retail company. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2020, 31, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-H. Human resource strategies in response to government cutbacks: A survey experiment. Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 1125–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Saridakis, G.; Blackburn, R.; Johnstone, S. Are the HR responses of small firms different from large firms in times of recession? J. Bus. Ventur. 2016, 31, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malik, A. Post-GFC people management challenges: A study of India’s information technology sector. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2013, 19, 230–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Garcia, E.; Sorribes, J.; Celma, D. Sustainable Development through CSR in Human Resource Management Practices: The Effects of the Economic Crisis on Job Quality. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 25, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, H.; Page, M. The Good, the Not So Good and the Ugly: Gender Equality, Equal Pay and Austerity in English Local Government. Work. Employ. Soc. 2018, 32, 789–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patterson, L.; Benuyenah, V. The real losers during times of economic crisis: Evidence of the Korean gender pay gap. Int. J. Manpow. 2021, 42, 1238–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prouska, R.; Psychogios, A. Do not say a word! Conceptualizing employee silence in a long-term crisis context. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 29, 885–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prouska, R.; Psychogios, A. Should I say something? A framework for understanding silence from a line manager’s perspective during an economic crisis. Econ. Ind. Democr. 2018, 40, 611–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roca-Puig, V.; Bou-Llusar, J.; Beltrán-Martín, I.; García-Juan, B. The virtuous circle of human resource investments: A precrisis and postcrisis analysis. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2018, 29, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okay-Somerville, B.; Scholarios, D. A multilevel examination of skills-oriented human resource management and perceived skill utilization during recession: Implications for the well-being of all workers. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 58, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitalaksmi, S.; Zhu, Y. The transformation of human resource management in Indonesian state-owned enterprises since the Asian Crisis. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2010, 16, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaidi, Y.; Thévenet, M. Managers during crisis: The case of a major French car manufacturer. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2012, 23, 3397–3413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vokić, N.P.; Klindzic, M.; Hernaus, T. Changing HRM practices in Croatia: Demystifying the impact of the HRM philosophy, the global financial crisis and the EU membership. J. East. Eur. Manag. Stud. 2018, 23, 323–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagelmeyer, S.; Heckmann, M. Flexibility and crisis resistance: Quantitative evidence for German establishments. Int. J. Manpow. 2013, 34, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaussaud, J.; Liu, X. When in China … The HRM practices of Chinese and foreign-owned enterprises during a global crisis. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2011, 17, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.I.; Huang, D.; Sarfraz, M.; Sadiq, M.W. Service Innovation in Human Resource Management During COVID-19: A Study to Enhance Employee Loyalty Using Intrinsic Rewards. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 627659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, J.; Bartram, T.; Pariona-Cabrera, P.; Halvorsen, B.; Walker, M.; Stanton, P. Management practices impacting on the rostering of medical scientists in the Australian healthcare sector. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinić, M.; Milićević, M.; Mandić-Rajčević, S.; Tripković, K. Health workforce management in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey of physicians in Serbia. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2021, 36, 92–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Castillo, R.; González-Caro, M.; Fernández-García, E.; Porcel-Gálvez, A.; Garnacho-Montero, J. Intensive care nurses’ experiences during the COVID -19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Nurs. Crit. Care 2021, 26, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortaghi, S.; Shahmari, M.; Ghobadi, A. Exploring nursing managers’ perceptions of nursing workforce management during the outbreak of COVID-19: A content analysis study. BMC Nurs. 2021, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salas-Vallina, A.; Ferrer-Franco, A.; Herrera, J. Fostering the healthcare workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: Shared leadership, social capital, and contagion among health professionals. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2020, 35, 1606–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldfarb, N.; Grinstein-Cohen, O.; Shamian, J.; Schwartz, D.; Zilber, R.; Hazan-Hazoref, R.; Goldberg, S.; Cohen, O. Nurses’ perceptions of the role of health organisations in building professional commitment: Insights from an israeli cross-sectional study during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021, 29, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasalvia, A.; Amaddeo, F.; Porru, S.; Carta, A.; Tardivo, S.; Bovo, C.; Ruggeri, M.; Bonetto, C. Levels of burn-out among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic and their associated factors: A cross-sectional study in a tertiary hospital of a highly burdened area of north-east Italy. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Faraz, N.A.; Ahmed, F.; Iqbal, M.K.; Saeed, U.; Mughal, M.F.; Raza, A. Curbing nurses’ burnout during COVID-19: The roles of servant leadership and psychological safety. J. Nurs. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Mao, Y.; Morrison, A.M.; Coca-Stefaniak, J.A. On being warm and friendly: The effect of socially responsible human resource management on employee fears of the threats of COVID-19. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 33, 346–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, V.; Srivastava, S. Hospitality and tourism industry amid COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives on challenges and learnings from India. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 92, 102707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Redondo, S.; Nevado-Peña, D.; Yañez-Araque, B. Ethics and Happiness at Work in the Spanish Financial Sector. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, P.E.; Goodman, D.; Stanley, R.E. Two Years Later: Hurricane Katrina Still Poses Significant Human Resource Problems for Local Governments. Public Pers. Manag. 2008, 37, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluger, L.C.; Alff, H.; Alfaro-Córdova, E.; Alfaro-Shigueto, J. On the move: The role of mobility and migration as a coping strategy for resource users after abrupt environmental disturbance—The empirical example of the Coastal El Niño 2017. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2020, 63, 102095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, D.-Y.; Lin, C.-H. Human resources planning on terrorism and crises in the Asia Pacific region: Cross-national challenge, reconsideration, and proposition from western experiences. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 47, 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fee, A.; McGrath-Champ, S. The role of human resources in protecting expatriates: Insights from the international aid and development sector. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 28, 1960–1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannon, J.; Paraskevas, A. In the line of fire: Managing expatriates in hostile environments. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 30, 1737–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornell, S.; Nickel, B.; Cvejic, E.; Bonner, C.; McCaffery, K.J.; Ayre, J.; Copp, T.; Batcup, C.; Isautier, J.; Dakin, T.; et al. Positive outcomes associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name of Country/Region | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Asia | 1 |

| Asian Pacific | 1 |

| Australia | 1 |

| Britain | 6 |

| China | 3 |

| Croatia | 1 |

| Europe | 1 |

| France | 1 |

| Germany | 4 |

| Greece | 2 |

| Iceland | 1 |

| India | 3 |

| Indonesia | 1 |

| Iran | 1 |

| Ireland | 1 |

| Israel | 1 |

| Italy | 1 |

| Japan | 1 |

| Korea | 1 |

| New Zealand | 1 |

| Norway | 1 |

| Pakistan | 2 |

| Peru | 1 |

| Serbia | 1 |

| Singapore | 1 |

| Slovenia | 1 |

| Spain | 7 |

| Sri Lanka | 1 |

| Switzerland | 1 |

| Thailand | 1 |

| USA | 4 |

| Vietnam | 1 |

| Name of Journal | Number of Papers |

|---|---|

| Asia Pacific Business Review | 4 |

| Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources | 1 |

| Bmc Nursing | 1 |

| Bmj Open | 1 |

| British Journal of Industrial Relations | 1 |

| British Journal of Management | 1 |

| Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management | 1 |

| Current Issues in Tourism | 1 |

| Economic and Industrial Democracy | 3 |

| Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja | 1 |

| Employee Relations | 2 |

| Engineering Construction and Architectural Management | 1 |

| Frontiers in Psychology | 1 |

| Global Environmental Change-Human and Policy Dimensions | 1 |

| Human Resource Management | 2 |

| Human Resource Management Journal | 3 |

| International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management | 1 |

| International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | 1 |

| International Journal of Health Planning and Management | 1 |

| International Journal of Hospitality Management | 1 |

| International Journal of Human Resource Management | 8 |

| International Journal of Manpower | 3 |

| International Nursing Review | 1 |

| Journal For East European Management Studies | 1 |

| Journal of Nursing Management | 2 |

| Leadership Quarterly | 1 |

| Nursing in Critical Care | 1 |

| Public Management Review | 1 |

| Public Personnel Management | 1 |

| Sustainability | 3 |

| Work Employment and Society | 1 |

| Research Method | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative | ||

| Interviews | 10 | 17.8 |

| Case study (5 multiple case studies) | 8 | 14.2 |

| Longitudinal interviews | 1 | 1.7 |

| Focus group | 1 | 1.7 |

| Written feedback | 1 | 1.7 |

| Quantitative | ||

| Survey, questionnaire | 19 | 33.9 |

| Secondary data | 1 | 1.7 |

| Mixed Methods | 10 | 17.8 |

| Total | 56 | 100.0 |

| Countries/Regions | Responses to Crises | HRM Practices | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asia China Indonesia Japan Korea | More emphasis on cost reduction and individual performance, Anglo-American approach, change of employment laws to enhance labour flexibility | Hiring temporary workers, bonuses, and individual performance system instead of group performance; less emphasis on seniority system; laying off workers; increased outsourcing and non-standard workers; increase in hiring university-educated workforce, but fewer women hired in times of recession | Aoki et al. (2014) Chang (2012) Cho et al. (2011) Patterson and Benuyenah, (2021) Sitalaksmi and Zhu (2010) Jaussaud and Liu (2011) Shen and D’Netto (2012) |

| Europe Croatia Germany Greece France Iceland Ireland Spain UK | Hard HRM, cutbacks, and pay freeze | Financial cutbacks meant that gender equality had less priority and support after the cutbacks and restructuring (Britain); work intensification, job enlargement, job losses, part-time jobs; pay freeze (Britain, France, Greece, Ireland, Spain), employee silence (Greece); outsourcing of HRM did increase partly and more emphasis on cost reduction, but few employees were laid off (Iceland); firms with employee ownership in 28 European countries were less likely to lay off staff and had higher firm performance; small firms tended to focus on pay-related cost-cutting whereas alternative HR measures were more evident in large organisations; large firms were more likely to lay off workers than SMEs; firms with formal HR practices showed more resilience to the downturn (Britain); the global financial crisis (hard HRM) was found to be the most plausible explanation for the majority of HRM changes that happened in the observed three-year period. However, both the HRM philosophy (more market orientation) and the European Union (EU) membership (changes in labour laws and training) were recognised to have a certain impact as well (Croatia); organisations in East and West Germany used different measures to deal with the crisis, such as searching for new markets, restructuring, hiring stops, short-working, etc. | Page (2018) Cook et al. (2016) Edvardsson and Teitsdottir (2015) Garmendia et al. (2021) Gunnigle et al. (2013) Johnstone (2019) Kim and Patel (2020) Martinez-Garcia et al. (2018) Prouska and Psychogios (2018, 2019) Lai et al. (2016)Patterson and Benuyenah (2021) Prouska and Psychogios (2018, 2019) Roca-Puig et al. (2019)Okay-Somerville (2019) Jaiti and Thevenet (2012) Vokic et al. (2018) Zagelmeyer et al. (2012) Zagelmeyer and Heckmann (2013) |

| America USA | Public officers’ response to the recession | Reordering of spending priorities, leaving vacant positions unfilled, reducing services, salary freeze | Kim (2019) |

| India | HRM changes in the IT sector | Hiring freeze, hard HRM, no pay increase, some reduction in training, less turnover | Malik (2013) |

| Professional Groups | Work Situations and Professional Response | HRM Practices | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nurses/health care professionals | Strict and unpleasant work situations and work–family conflict; workload and patient isolation increased and affected the way nursing was carried out negatively; shock, worry, isolation, a lack of confidence, and physical exhaustion; burnout, emotional exhaustion, and cynicism; reassignment to other positions; increased infections; absenteeism; no control overwork | Social, motivational psychological, and preventive rewards/measures by organisations to increase loyalty and retention; satisfaction with the hospital policy and strategies implemented during the outbreak, acknowledging the importance of support from nursing leaders; providing pandemic-related training and support; dissatisfaction with workplace preparedness; shared leadership, information sharing, and trust leading to reduced infections; servant leadership reducing burnout and increasing psychological safety | Cavanagh et al. (2021) Abdullah et al. (2021) Fernandez-Castillo et al. (2021) Gao and Tan (2021) Goldfarb et al. (2021) Lasalvia et al. (2021) Ma et al. (2021)Poortaghi et al. (2021) Dinic et al. (2021) Salas-Vallina et al. (2020) |

| Professionals in hospitals and the tourism industry | Employee fears of external threats; illness; stuck at sea, isolation, unhappiness | Tourism and hospitality businesses did use both defensive and offensive responses to survive the pandemic that included the protection of human resources, job redeployment, and performance management; sustainable HRM did decrease employee fears; better crisis preparedness needed; poor HRM leadership by cruise-line operators; employee-centred HRM strongly impacted employee well-being | Agarwal (2021) Sun et al. (2021) He et al. (2021) Srivastava (2021) Radic et al. (2020) |

| Other professions | A change in values towards social responsibility and training, going beyond the achievement of a socially acceptable income; remote working; between 2017 and 2020 five out of 10 of the most important analysed motivational factors overcame the significant change in the value of importance from the point of view of the time studied; emotional exhaustion due to unfinished tasks | A softer approach to managing employees can be used during a crisis; organisational values and job motivation can enhance organisation commitment during remote working | Adikaram et al. (2021) Castellanos- Redondo et al. (2021) Koch and Schermuly (2021) Redondo et al. (2020) Tanpipat et al. (2021) |

| Incidents | Work Situations | HRM Practices | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Earthquakes in New Zealand; Hurricane Catherina, USA; flooding in Peru | Skill shortages; rapid staff turnover; lack of information regarding infrastructure recovery experts; smaller cities and towns on the Gulf Coast continue to struggle with hiring and retaining qualified employees; migration of people, people moving to other sectors | A need to improve information about experts and skills | Cavanagh et al. (2021) Sun et al. (2021) Chang-Richards et al. (2017) French et al. (2008) Kluger et al. (2020) |

| Indian Ocean tsunami | A need for extra manpower and funding to tackle the consequence of the tsunami | Despite an influx of volunteers, the global disaster challenged multinational non-profit organisations’ ability to have enough skilled and experienced staff to respond to the tsunami and maintain existing workloads. | Merlot and De Cieri (2012) |

| Incidents | Work Situations, Employee Response | HRM Practices | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bombing in Oslo, Norway; 9/11 in the US; two bombings in Bali | Post-traumatic stress | Management support decreases post-traumatic stress, perception of leadership is not affected by the crisis situation; a functional HR plan must include elements for proactive alertness, the ability to dispatch inventory, evacuation plans, and record preservation coupled with dissemination to employees and explicit employee training and cross-cultural management | Birkeland et al. (2017) Liou and Lin (2008) |

| Protecting expatriates in international non-profit and for-profit organisations | A need for extra manpower and funding to tackle the consequence of possible attacks | The organisations seek to build in-house competence centred on culture building and supported by a suite of human resource practices relating to people services, information services, and communication services. These competencies coalesce around an overarching philosophy towards safety and security that we describe as personal responsibility and empowerment; there is a difference between industries; the importance of specialist expertise, knowledge and management of human resources in hostile environments is highlighted | Fee and McGrath-Champ (2017) Fee et al. (2019) Gannon and Paraskevas (2019) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Edvardsson, I.R.; Durst, S. Human Resource Management in Crisis Situations: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12406. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212406

Edvardsson IR, Durst S. Human Resource Management in Crisis Situations: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability. 2021; 13(22):12406. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212406

Chicago/Turabian StyleEdvardsson, Ingi Runar, and Susanne Durst. 2021. "Human Resource Management in Crisis Situations: A Systematic Literature Review" Sustainability 13, no. 22: 12406. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212406

APA StyleEdvardsson, I. R., & Durst, S. (2021). Human Resource Management in Crisis Situations: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability, 13(22), 12406. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212406