Abstract

Questionnaire-based surveys are among the most widespread data collection methods in tourism research. However, the special features of rural tourism, with frequently spontaneous, non-massive visitation patterns and sparse visitor numbers, pose challenges to onsite questionnaire administration. Researchers must address these problems to make sample recruitment easier and more effective, while maintaining the goals of representativeness of population and data validity. Using the rural wine tourism context, this article identifies the major challenges for questionnaire-based onsite surveys and suggests best practice procedures. Challenges are discussed using three complementary perspectives: of the supply agents, of the research subjects (the visitors) and of the researchers. The article presents the theory and case study-inspired reflection on the potential strategies of overcoming these challenges and guaranteeing the largest possible number of visitors surveyed in contexts where visitors are few. The discussion includes the questionnaire’s characteristics; the physical setting of its administration; the researchers involved; the visitors approached; the social interactions and influences occurring during the process. Issues with the future use of alternative online forums are also discussed.

1. Introduction

Wine tourism is a developing sector within rural tourism that has attracted growing attention worldwide [1], manifested in investments in new vineyards and wine tourism experiences [2,3]. Its expansion can bring several benefits, one of the most important being the development of rural areas where such tourism occurs [1]. This development frequently happens in a relatively spontaneous way, driven by independent travelers exploring the wine-producing destination, its diverse attractions and services [4].

In light of the potential added value of wine tourism and its academic context, recent decades have seen increasing research in this area. A systematic literature review of the wine tourism field [5] considered studies published between 2001 and 2019. In the first nine years (2001–2010), the authors found 17 scientific articles, while for the last nine years (2011–2019), this number more than doubled, rising to 43 articles.

Despite this, an empirical data-inspired reflection on optimal visitor data collection in wine tourism is still missing, but it should be paramount for marketers and managers to design more efficient strategies to reach consumers and thus encourage the promotion and development of innovative, high-quality wine tourism products [6]. Accordingly, this article explores and reflects on issues related to gathering research findings on rural wine tourism, where both resources for such research and visitor flows are limited. One of the most widespread and unanimously used data collection methods is questionnaire-based surveys. However, the authors of this article consider that the features of wine tourism, particularly in rural areas characterized by limited numbers of visitors, pose special challenges to questionnaire administration that should be addressed in order to make sample recruitment procedures easier and more effective. The article identifies the main challenges of visitor sample recruitment for questionnaire-based surveys of rural wine tourists and suggests effective ways of addressing them. The authors’ reflections stem from their experience within several rural tourism projects but focus particularly on insights from the visitor data collection process within the three-year project TWINE (co-creating sustainable Tourism & WINe Experiences in rural areas (2019–2021)). After an introduction to rural wine tourism and a discussion on the importance of market research in this field, the methodology of visitor survey data collection in the TWINE project and that of participant observation and informal interviews is presented. The main survey challenges are identified, distinguishing between those caused by supply agents, by visitors and by researchers. Recommendations are made for addressing those challenges. The conclusions present the implications and limitations of those recommendations, as well as avenues for relevant future research in survey data collection in niche tourism contexts.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Wine Tourism in Rural Areas

Wine tourism is a form of ‘special interest tourism’ [1] and often overlaps with rural tourism motivated by curiosity about wine-producing territories, their products, traditions, landscapes and people [2,3,4]. Wine tourism is at the intersection of the wine production and tourism sectors [4] or, more specifically, agritourism [5,6] as it provides contact with farms, vineyards, wineries and other elements that characterize certain rural areas. It is an alternative to the mass tourism that typically occurs in sun and beach or winter ski destinations or in easily accessible urban areas, with clustered attractions within short distances [7]. Among many possible definitions, wine tourism can be understood as a visit to vineyards, wineries, festivals and shows related to wine, of which wine tasting and/or contact with the attributes of a wine region are the main motivating factors for consumers [8]. However, a more comprehensive definition of ‘terroir tourism’ or the wider tourism exploitation of wine-growing territories has also been accepted [9,10]. In this sense, wine tourism refers to the act of traveling with the objective of visiting, getting to know and living experiences in wineries and wine regions, as well as exploring their relationship with the region’s culture and local lifestyles [11].

It should be noted that wine tourists do not always have a planned and conscious purpose of making a visit related to wine [12,13]. According to Getz and Brown [14], wine tourism demand results both from those primarily motivated to visit wine-producing regions and establishments and those who travel to those regions for other, broader, rural tourism reasons, occasionally also enjoying more specific wine tourism experiences.

Many wine businesses invest in wine tourism as a diversification strategy to wine production, yielding increased wine sales and strengthening wine and territory branding [15]. Rural wine-producing regions often host a number and variety of interesting, but relatively unimportant and regionally scattered natural and cultural heritage attractions and small-scale service establishments that do not attract large tourist flows, a condition frequently found in rural territories and one that hampers tourism’s economic sustainability if not adequately addressed [16,17]. Some wine-producing rural areas try to increase their appeal as tourist destinations through wine tourism, which may add value to an overall ‘authentic’ rural tourism experience, particularly if well-connected to the regions’ natural and cultural heritage and traditions [9]. Therefore, other economic and cultural sectors may also benefit from wine tourism, all of which promotes the quality of life of local communities and can conserve and enhance their cultural identity [18], thus contributing to sustainable regional development [6,19,20].

However, to yield such ambitions, sound market knowledge is needed [16], based on visitor survey research to help shed light on the needs and desires, behaviors and preferences of the market, as well as any conditioning factors informing the design of appealing and distinctive tourism products and the marketing and sustainable development strategies critical to success.

2.2. Visitor Survey Methods

The importance of the research activity in tourism transcends the obvious transversal contributions to this type of activity, as many of the current models in tourism are imported from other areas without any scientific validation [21]. It is, therefore, essential that the systematic research process and research methods themselves become the object of study and reflection not only in an academic context, but also to get more useful and valid practical contributions, plus, in some cases, improving the context of teaching/learning and supervising student research projects [22,23]. The growing relevance of quantitative research from the 1980s onwards was felt in the social sciences in general [24] and in tourism in particular, with questionnaires becoming some of the most widespread methods to collect primary data in tourism [21].

Visitor surveys are key instruments permitting better targeting of specific segments and niches via segmentation studies [25,26,27,28,29] or the identification of central factors explaining online travel purchases [30] or of increasing loyalty to a destination [31,32,33] or those contributing to appealing and memorable experiences [34,35,36]. They can also help increase the purchase of local products, both on- and off-site [37], or generally increase expenditures at the visited destination [38,39]. They also allow the longitudinal comparisons of visitor profiles and attitudes [40].

According to Finn et al. [21], questionnaire research involves ten steps/phases: (1) identify and define the problem being investigated; (2) identify and define appropriate measures and concepts; (3) determine the sampling strategy; (4) build the research instrument; (5) perform a pretest of the research instrument; 6) redefine and modify the research instrument and the implementation process; (7) administer the research instrument; (8) encode and process data; (9) analyze the data; (10) write the report. Some authors [22] consider the definition of the sampling strategy, the construction of the research instrument and its implementation as being the most critical phases of this process. The researcher often has to overcome many technical difficulties, and it can have a fundamental role in the success or failure of an investigation.

Data from visitor surveys are thus a relevant planning, management and marketing asset and require careful research design, beginning with a clear definition of the problem to be solved. Sampling is a particular challenge given the nonexistent sampling framework for a non-static and continuously changing universe of visitors, about which there is usually only outdated (1–2 years old) information in the form of tourism statistics, eventually useful for approximate quota sampling (assuming a relatively stable market). However, these secondary data are often incomplete, excluding tourists visiting friends and family or not using the official accommodation establishments. They also usually do not distinguish types of tourists by motivation or activities sought, making it difficult to distinguish special-interest tourists or even only leisure (versus business) travelers [41]. For visitors not staying overnight, the statistical framework tends to be even poorer, suggesting as an alternative ‘cluster sampling’ defined by time and space, administrating the survey at diverse times and at typical attraction/visitation sites through the year in a particular destination. The second most common challenge is to obtain a sufficient number of valid responses, particularly if using a more complex questionnaire, frequently leading to suboptimal samples of self-selected respondents. It requires a careful research plan, well-selected locations for administrating the survey, well-trained, empathetic but assertive researchers applying the survey, all leading to a high response rate, measured as number of responses obtained.

However, few articles reflect on the difficulties of data collection in this complex field or try to develop recommendations for addressing those challenges, which are especially severe in rural or niche tourism contexts. Moswete and Darley [42] are a worthwhile exception: they discussed the particular challenges researchers face in sub-Saharan Africa. Many other studies refer to methodological challenges and limitations, but without focusing on this relevant issue for its own sake.

3. Methods

The TWINE project, whose data collection issues inspired this article, studies the market for and issues involved in cocreating integral tourist experiences in rural wine destinations based on a study of three contrasting wine routes in Portugal’s Central region: Bairrada, Dão and Beira Interior. It involves the University of Aveiro (coordinating the project and responsible for data collection in the Bairrada region), the Polytechnic Institute of Viseu (responsible for data collection in the Dão region) and the University of Beira Interior (responsible for data collection in the Beira Interior region), as well as experts in destination marketing, consumer behavior research, economy, sociology, agronomy, sustainable rural tourism, wine tourism and regional development. It focuses on tourist experiences as cocreated and shared by and impacting tourists, local residents, agents of supply and other stakeholders from the tourism and wine sectors.

3.1. The Case

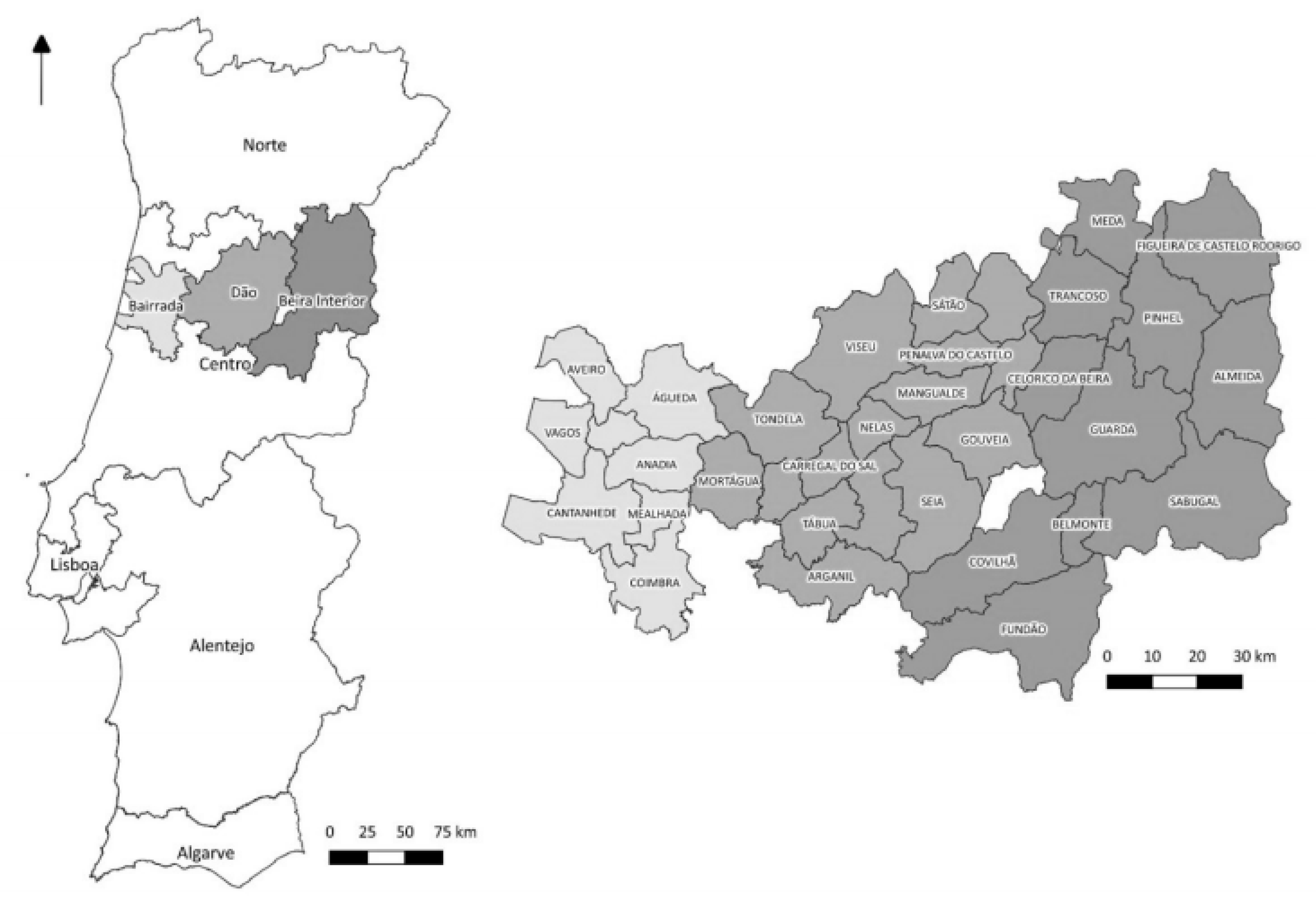

The Bairrada, Dão and Beira Interior wine routes are located in the center of Portugal (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Bairrada, Dão and Beira Interior wine routes.

The Bairrada region, located in Beira Litoral, between Aveiro and Coimbra, has a long wine-making tradition. Represented mainly by small-scale wineries, Bairrada is the main Portuguese region for sparkling wine production. Officially demarcated in 1979 and well-known for the quality of its wines, especially of sparkling wines, Bairrada offers a wide range of experiences related to wine, local food (e.g., suckling pig), thermal spas, culture and nature. The Bairrada Wine Route (BWR) was created in 1999 and, consequently, the establishment of BWR signage throughout the region has been improved to facilitate and promote access to participant members and to engagement in wine-related attractions [43].

The Dão Wine Route (DWR) was created in 1995 and is part of the demarcated Dão wine region (established in 1908), the first demarcated region for non-liqueur wines in Portugal. The Dão Wine Region promotes, besides the Dão Wine Route, other types of events and festivals which promote rural tourism and the actors involved in wine tourism [44]. Tourists in the DWR can also taste local gastronomy, appreciate beautiful landscapes and enjoy the historical, architectural and cultural heritage of its rural areas [44].

The recently created Beira Interior Wine Route (BIWR) encompasses 12 municipalities, and despite not all of the municipalities having wine production, they all have something that justifies their inclusion in the route, such as monuments or hotels. The wines are influenced by the surrounding mountains of Estrela, Marofa and Malcata and by the altitude of between 400 m and 700 m. The combination of granitic soils and harsh climate results in white wines of great aromatic exuberance and freshness plus red wines with complex aromas of wild fruits and spices, combined with a marked freshness. In recent years, there has been a great increase in the number of producers and wine quality in this region.

3.2. Methods of Visitor Data Collection and Systematic Inquiry about Best Practice

Visitors to wine routes are seen as central to economically sustainable development; understanding their motivations, preferences, behaviors, perceptions, sensations and emotions, conditioning and the integrating dimensions of experiences at the destination is therefore vital. The TWINE project used both a qualitative approach based on thirty in-depth visitor interviews on-site in each route and a quantitative approach via questionnaire-based surveys, yielding 1500 participants, 500 in each of the three regions. The method of (occasionally assisted) self-completion of a 3.5-page-long questionnaire was chosen.

The questionnaire consists of four parts: (1) motivations for the current visit, (2) features of the current visit (e.g., length, accommodation used), (3) link to the region visited and to the wine, and (4) visitors’ socioeconomic profile. With three closed-ended questions, including the main sites/places/attractions visited, the aspects most and least liked, a few multiple-choice questions (e.g., reasons for the visit, means of transport used) and many seven-point Likert-type scales, it would take respondents between 15 min and 25 min to complete. Some visitors required orientation on questions and others discussed with research assistants some of the content requested.

The survey took place from August 2019 to September 2021 on different weekdays and in diverse months, addressing visitors in specific touristic sites located in the territory of the three wine routes. The most common sites for survey administration were wineries, accommodation units and museums, but also coffeeshop terraces and parks, as the focus was on the broader wine terroir experience rather than on winery visitation. A cluster sampling approach was used, defined in place and time, addressing all visitors of attraction sites that were identified as tourists in these locations and in specific timeframes, resulting in an overall sample constituted by numerous subsample clusters. This procedure should be most adequate to yield an approximately representative sample, particularly in the context of an unknown and fluctuating population/sampling framework, as is typically the case in visitor surveys [22,41].

Most of the data collection was carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced the authors of this article to pay even more attention to issues related to data collection, at a time when visitors were still rather rare. It was necessary to reflect on the best strategies to optimize the fieldwork and guarantee the necessary number of participants while also achieving other objectives of data quality and validity with a mixed-method framework.

In this sense, based on participant observation, by carefully observing visitor behavior, persuading visitors to engage in the study, registering their responses and holding regular meetings with all research teams in the three regions, the authors developed a framework of ‘best practice’. This framework was discussed and reformulated based on the authors’ previous rural research experience and in joint reflection with other experienced researchers in the team until reaching the systematization of ideas shared in this article. Furthermore, ideas were also discussed with the agents of supply, who were central to facilitating (or hindering) our data collection on-site. This permitted validation of the authors’ perceptions as well as obtaining additional insights regarding barriers and challenges to the survey approach, particularly from the agents’ viewpoints.

We present those challenges below, enriched with discourses and examples from our fieldwork, informal interviews, feedback from research assistants and participant observation.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Challenges to Sample Recruitment in Rural Wine Tourist Markets

Sample collection per se is probably one of the most challenging and demanding steps in the research process: it takes time, it consumes researcher effort, and it is dependent on the subjects’ voluntary collaboration. The difficulties become even greater when these processes are developed without sufficient financial and human resources, and there is often no way to directly compensate participants for their collaboration. Furthermore, as a niche tourism segment, wine tourism in rural territories poses additional challenges (see below). We list below the challenges inherent in the collection of data by means of a questionnaire in wine tourism contexts in the following categories: those linked to (a) supply agents, (b) visitors and (c) researchers.

4.1.1. Challenges Linked to Supply Agents

Wine tourism is frequently associated with niche tourism markets, with studies on the wine tourist’s profile suggesting their belonging to an upper middle class [12,19,45,46], often associated with some social elitism. This may contribute to making supply agents more zealous about their business and reluctant to any potentially threatening element of the “comfort bubble” that they have built to receive their customers. Many suppliers fear possible annoyance caused by filling out a long questionnaire. They stressed in informal conversations about the survey approach that they did not want to risk the questionnaire becoming more memorable (in a negative way) than the wine tourism experience itself:

“I remember having visited the [wine producing region of] Douro once and having participated in a research project. Whenever I think about that weekend, I remember first this long and boring questionnaire. This is what I want to avoid, that visitors to the Bairrada Route feel the same and see their experience tainted by such a questionnaire”.(Association of the Bairrada Route, administration)

“I would never authorize a procedure of this type (referring to the administration of the TWINE survey) because this winery should not be associated and remembered due to a survey, but rather for its wines, perfect hospitality, well, for the singular experience that it took us years to refine… I will not go a step back and present our visitors a dreadful questionnaire as they do in those shopping malls”.(producer, Beira Interior)

When this happens, supply agents could feel that the presence of the researcher (if applicable) and the administration of the questionnaire negatively disturbed the experience they offer the clients. In these cases, supply agents often did not authorize data collection on their premises, even though they recognize the added value of the research for their own business.

“We do have very special clients that feel that they pay a good [high] price for a service and that, because of this, they must be served in the very best conditions… Well, they like to be pampered, if you understand, and this does not match with such survey requests from universities”.(producer, Bairrada Route)

Another relevant aspect is related to this last topic—understanding the relevance of the study. Some suppliers do, however, understand the importance of research and its medium- and long-term return for their own business and, correspondingly, supported the survey:

“These [surveys] are very welcome and I even highlight our collaboration on our webpage since I think that this [involvement] brings us prestige and credibility. Apart from this, when the data are obtained here, apart from the obvious contribution to the progress of science, the results apply very well to us and will thus be important inputs to improving our business. By the way, it is not the first time that we introduce changes [in our operations] due to university studies”.(producer, Bairrada)

However, other agents, either because of issues related to lower levels of education or to personal insensitivity to scientific themes, fail to understand the importance and practical implications of research for the development of wine tourism. In these cases, supply agents see their relationship with the researcher as parasitic rather than symbiotic, which naturally hinders the communication processes (for example, the researcher tries to contact the agents successively without success) and interpersonal relationship processes in general, always implying the idea that the supply agent is doing a great favor to the researcher, which is presented almost at the personal level. For example, the implicit narrative of the supply agent, in those cases, could be something like:

“I am helping you to do your job” (producer, Dão) or “We have already helped you several times, but it would be better to try at different places next… It is a responsibility of all, but one that does not give us anything in return, on the contrary, in the short run”.(producer, Bairrada)

This argument may also be associated with the ‘not in my backyard syndrome [47] and the problem, correctly perceived as unfair, of others (in this case, of competitors) taking advantage of these businesses’ availability and efforts to support research that is relevant for all while others do not get involved and thereby may even present themselves as apparently ‘more attractive’ to visitors.

4.1.2. Challenges Imposed by Visitors

Having crossed the barrier of supply agents, not all visitors were inclined to participate in the study. At this level, one of the main difficulties is time. Leisure time, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, becomes much more valuable than any other and should not be felt, as reported by some visitors, as being wasted on surveys.

“We have very short time here, we only stay for the weekend and have a reservation for our suckling pig lunch at the restaurant within 20 min from now, well, we actually came here mostly for that lunch, so we just don’t have any time for this [survey]”.(family visitors at the Wine Museum, Bairrada)

“No thank you, I am sorry, but I came really to relax and enjoy the experience. I have no patience for such things right now”.(visitor at a winery, Caves Aliança, Bairrada)

An even more aggressive (however rare) reaction by one of the visitors confirms the fear of some of the abovementioned supply agents:

“To be honest, I don’t understand how they can accept your presence here, this is a service I pay for and there shouldn’t be such requests in such a context. They even prohibit such approaches in restaurants and coffeeshops, I don’t understand”.(visitor at a winery, Caves Aliança, Bairrada)

Therefore, the challenges observable amongst visitors are related to lack of time, especially when travelling in large groups (excursions or organized visits) and to the lack of sensitivity to scientific matters. Sometimes, visitors feel that they are being disturbed during a service they are paying for (for example, when visiting a winery), which makes them angry both with the researcher and the supplier.

4.1.3. Challenges Imposed by Researchers

The researcher finds numerous challenges in this context. However, perhaps we can consider the biggest one is managing the balance of purposes and the need to not pursue too many and too detailed research objectives. The researcher’s objectives/purposes are not always compatible with the purposes of supply agents and/or with those of visitors. Thus, the researcher often intends to analyze multiple and complex variables that translate into extensive protocols, but they are incompatible with the visitors’ priority to make the best use of their time and with the purpose of the agents of the supply not to upset their customers with lengthy and boring questionnaires. There were several TWINE team meetings in which researchers discussed and reflected on the constructs to be included in the questionnaire, being difficult to satisfy the research interests of the entire multidisciplinary team without compromising the size of the research instrument. Often, the questionnaire went through several development stages until reaching the most condensed version possible, requiring strong and great assertiveness on the part of the project coordinators to maintain a well-defined focus.

As for the data collection process, additional challenges relate to the recruitment, training and motivation of research assistants that are equally capable of developing an empathetic, while assertive and convincing approach to visitors that are less inclined to participate. Assistants have to be able to convert respondents to their “side” and help them participate with a positive attitude. Communication skills, experience on-site and a thorough understanding of the questionnaire and its purposes are the most important issues here. Researchers collecting the data must understand the visitors’ perspective and try to present the survey in the most credible way, as wrong first impressions may occur:

“I am sorry, my dear, but whenever I see persons [like you] addressing people [on the street], I think at first of somebody who wants me to buy something I do not need or who intends to ask me for money, I truly have no patience for such a thing”.(visitor to a winery, Caves Aliança, Bairrada)

4.2. How to Maximize Adherence to the Study?

Regarding the abovementioned challenges, we must question ourselves how the researcher may maximize adherence to a survey, i.e., how to recruit and obtain valid responses from as many respondents as possible in a niche tourism context. We next tried to answer this question considering the characteristics of the questionnaire to be administered, the characteristics of the researchers involved, the setting, evolving interpersonal relationships and the processes of social influence.

4.2.1. Questionnaire

The way in which the questions are presented can make the difference to encouraging people to accept (or not) and complete the questionnaire. For example, some people ask to see the questionnaire first and then decide whether to complete it. Thus, for the reasons already mentioned, the questionnaire must be as brief as possible [48,49,50].

In addition, esthetically, the questionnaire must be appealing and clean (e.g., paper and print of good quality, appealing layout facilitating the reading and understanding of instructions and content) [49,51]. The questions must be formatted so that the information does not appear too dense, that is: (1) not too small letter size (preferably font size 12 or larger); adequate spacing between questions; short and objective items to facilitate understanding and reading. In this sense, the use of underlining and bold formatting can also be an advantage. The perceived size of the questionnaire does not depend only on the number of questions and items presented. Too much space is often wasted on unnecessary statements and introductions to the issues. Thus, preferably, whenever possible, the scales or type of response should be formulated in the same way so that a single instruction could serve as many questions as possible.

It is important that the structure of the questionnaire allows an almost automatic answer, allowing the subject not to think about anything other than the item itself. For example, in the case of Likert scales, it is important that the legend is presented at least at the beginning of each scale so that the participant does not have to actively seek this information. Furthermore, probably because they demand a more active and involved attitude, open-ended questions result (in our experience of the Twine and other tourism projects) in a high number of missing values. On the other hand, the type of data obtained from these types of questions helps to complement, obtain detail and provide new insights for a better understanding and interpretation of the data obtained from the more quantitative questions. For this reason, even if the number of answers to these questions is lower, it is worthwhile considering the inclusion of these types of questions. The questions must be clear and objective, as straightforward as possible, avoiding ambiguities, and they must be formulated in everyday language, avoiding too technical vocabulary [49,51].

Particularly for younger age groups, presenting the questionnaire on a tablet can be an interesting option. In addition, even when the collection takes place in person, it can be useful to have the questionnaire on an online platform as some people are not available to answer at the particular time (perhaps due to lacking time during a tight tour schedule); however, they may agree to do it later. Thus, if we can provide a card with the project’s website and the link to the questionnaire, in addition to transmitting a professional image, we increase the chance of recruiting a few more participants.

4.2.2. Setting

In the particular case of wine tourism in rural areas, data collection from visitors can take place in various places, from wineries, restaurants and local accommodation units to green spaces, among others. It is necessary to have basic conditions that guarantee the comfort of the visitor participating in the task, making it as pleasant as possible. The most sympathetic conditions at the data collection place (for example, in a wine cellar) provide the possibility of using a space specifically for that purpose, allowing people to sit comfortably, providing them with a pen (preferably personalized with the logo of the host institution of the study). This space can be improved with an informational poster about the project and the research institute, conferring extra credibility to the study. When possible, filling out the questionnaire should be more pleasant if integrated into a visit activity such as wine tasting or while resting in the hotel lobby or at the swimming pool in order to minimize the feeling of wasting time. However, this aspect requires excellent coordination with the supplier. In addition, the researcher himself can offer small treats to the participant while she/he fills out the questionnaire, perhaps something to eat or drink. An appealing communication context can be created through expressing interest in the visitor’s experience and opinions, highlighting the importance of their responses for real improvements to wine tourism in the region. All of these factors increase the perceived appeal and credibility of the study, create a sense of professionalism and make it clear that there is a partnership between the researcher and the supplier as well as with the wine route as a regional entity with the responsibility over more sustainable tourism development, making the whole process more relevant to the respondent. Furthermore, an environment of personal bonding, trust and compromise may be developed by researchers showing empathy and availability to help out as much as possible in getting to know something about the destination in such a more informal, but very important, personalized interviewing context. When it is not possible to create a space with these characteristics, perhaps because data collection takes place outdoors, it is important to provide at least the necessary materials to answer the questionnaire with takeaway pens and writing pads. In addition, and in any of the situations, it can be motivating to offer some reward to the participant, even if only symbolic (e.g., a small bottle of wine or local fruit). They could even be presented when requesting participation. These items may serve as souvenirs of pleasurable moments on the wine route, making the survey experience context and the interaction with university researchers pleasantly memorable.

Some basic conditions must be guaranteed in all cases, such as adequate lighting, a quiet environment without too much background noise, a place protected from harsher climatic conditions (e.g., excessive heat in summer), as well as helpful monitoring by the researcher throughout the entire process.

4.2.3. Researcher

The researcher must introduce him/herself in a way that creates a form of relationship with those interviewed and demonstrates deep knowledge about and enthusiasm for the study. It is essential to create a relationship of trust and goodwill between the interviewer and the respondent so that the respondent feels comfortable and not threatened by the study situation [49,51,52]. The way in which the researcher presents him or herself can also be a determining factor in persuading visitors to participate in the study, even if initially not inclined to. Clothes should be well-chosen and adequate for the situation. Researchers should not look too formal so as not to create too much interpersonal distance or fear of approach. On the other hand, they should also not be too informal and carefully avoid a sloppy and unprofessional image. Discreet clothes with which he/she feels comfortable and that allow him/her to convey a confident and reliable attitude are vital. The researcher should always identify him-/herself, for example, by using an institutional badge indicating the researcher’s name and function [52]. In addition, and more importantly, the researcher could benefit from his/her interpersonal skills if he/she can use them to create a “kind of interpersonal magnetism”, showing respect for the time and space of the visitor and sincere interest in their visit. It is essential that the researcher’s attitude is sympathetic and empathetic, conveying an image of professionalism, knowledge and credibility and showing the respondent that he/she is contributing to a relevant research process [52]. The visitor must understand the purpose and value of the study so that he/she feels that he/she is participating in something useful, in a symbiotic logic and not in a parasitic logic, as mentioned regarding supply agents. The researcher’s posture must be visibly collaborative, making clear the voluntary nature of participation [52] and providing all the necessary information so that the client can decide on his/her participation in an informed manner.

The way in which the researcher approaches people and invites them to participate in the study must be kind, balancing the formal discourse necessary to frame the study with an empathetic attitude recognizing the visitors’ effort to spend their precious leisure time participating in the study. The researcher must, in this sense, optimize the privacy of the response conditions, maintain neutrality and confidentiality, know how to listen and not insist with regard to sensitive issues [52]. After the subject’s participation, the researcher must express sincere appreciation for the visitor’s help, if possible, with some reward, but at least through their speech, maintaining a posture of gratitude throughout the interaction with the participant. It is also common for people not to want to participate in the study, and some are not always kind or polite in responding to the researcher’s request. In these cases, it is essential that the researcher remains empathetic, transmitting a posture of true understanding due to the voluntary nature of participation in the study and even regretting/apologizing for the inconvenience caused by the request if he/she realizes that the person felt uncomfortable.

In addition, it is very important that the researcher is not discouraged by negative responses, and it is essential that a bad experience with a visitor (for example, a less sympathetic response) does not contaminate the next experience. Thus, researchers must learn to treat each approach/invitation that they make as if it were the first of the day, maintaining the enthusiasm, sympathy and positive energy that will necessarily influence the invited visitor and the atmosphere around data collection, requiring patience, resilience and an overall positive and confident attitude.

The researcher must be able to moderate her/his “thirst” for knowledge, control their desire to want to know more and more and accept that fewer questions answered and incomplete answers may result in more and better information than a complete rejection of response. Thinking strategically, in a medium- and long-term logic, positive experiences perceived by suppliers and visitors could open the door to future collaborations. The researcher should also seek to establish from the start a trusting and secure relationship with the supply agent in order to articulate with him/her, so that the supplier may understand his/her role as a partner in a project in his/her own interest.

A final note to research assistants that is frequently required must be mentioned. Since the interaction between the researcher administrating the questionnaire and the visitors is of crucial importance, the research assistants contracted for the purpose need to be well-recruited, considering their communication skills (as well as English proficiency) and personal profile for the task, but also introduced to the study and briefed about procedures and coping with possible and even probable challenges. Continuous feedback and close contact with the researcher coordinating the data collection process and, finally, regular conversations with the overall project coordinator for addressing and possibly solving problems are an essential part of an ongoing project with over a year of intense data collection from diverse stakeholders and participants.

In regional and even nationwide tourism projects, sometimes diverse teams work in different locations gathering data for a pooled data base, as in the TWINE project. In the latter, these meetings additionally required articulation between three research teams in geographically distinct territories (wine routes) in Portugal. These coordinating meetings were fundamental for guaranteeing a consistent, enthusiastic and successful research approach, exchanging best practices and finding optimal solutions for each territory, thus yielding an optimal amount of high-quality data. Here, specific socioeconomic and geographic territorial features, as well as personal contacts amongst researchers in the respective responsible teams were additional important aspects helping (or hindering) the identification of solutions.

4.2.4. Social Influence

There are some ideas from the theoretical body of social psychology revealing how social influence can help optimize data collection in groups of visitors (e.g., in the context of TWINE, events such as thematic fairs or dinner presentations and the tasting of specific wines, excursions, etc.). That is, in a context where visitors are scarce, such as in wine tourism, the opportunity to collect data from larger groups of visitors should always be instigated by the researcher. In these cases (relatively rare in rural tourism), it is essential that researchers take advantage of the principles of social psychology to maximize adherence to the study.

Social influence can be defined as a driver of individual behavior in the social context, occurring when the actions of one person are a condition for the actions of another [53]. In other words, someone’s behavior is socially influenced when it changes in the presence of others [54]. Individuals have a generalized tendency to organize their experiences, establishing relationships between internal or external stimuli at every moment, creating functional units that provide limits and meaning to what is experienced (the concept of the ‘reference frame’). That is, the experience at a given moment always depends on an implicit comparison with the experience immediately preceding it. Sherif [55], one of the most outstanding authors in this field of research, concluded from his experience that individuals, when exposed in groups to an ambiguous situation, use the behavior of others to construct their individual frames of reference. In addition, authors such as Asch [56] called attention to the phenomena of social conformity in which individuals tend to follow the behavior of other members of the group. Apparently, people conform for two main reasons: because they want to fit in with the group (normative influence) and because they believe the group is better informed than they are (informational influence).

Thus, it seems obvious that if, at first, the researcher succeeds in persuading some individuals to participate in the study, it significantly increases the probability of others present in that event/group also participating due to processes of social influence generating a snowball of interest around the presence of the researcher and participation in the study. In this sense, when the researcher starts collecting data of this nature, he/she must invest some time in observing the potential subjects. For this purpose, in our research project, it was found useful to create a kind of ‘information desk’ with information about the project (brochures, posters), the necessary materials (pens, questionnaires) and any gifts to offer to participants (in the TWINE case—bottles of wine). Having a research space allows the researcher to have, on the one hand, a point of observation of those present and, on the other hand, to be observed by them, generating curiosity. Some more curious persons may take the initiative to approach and ask for information about the researcher’s purpose in the event/context. When this happens, it is an asset if the researcher succeeds in captivating these persons and persuading them to participate as it deconstructs a ‘persecutory image’ that is often created around the role of who recruits participants for surveys.

However, in fact, most people do not approach: it must be the investigator that approaches them, and just before beginning this more direct approach, the researcher should invest time to gather a set of signals about who is the best candidate to be the first one invited to participate in the study in order to create a positive influence on others. Thus, the researcher observes and seeks to “feel” the potential participants, locating people who show some signs of greater receptivity that must be taken into account. For example, establishing a friendly eye contact, caring smiles, reading and commenting on the information available on the poster/leaflet. On the contrary, other people are immediately less receptive to participate, avoid eye contact or look with an air of disdain or even make derogatory comments. Usually, people who have done research within their academic and/or professional career are more sensitive and receptive to participation in other studies. Of course, the researcher at the outset does not know who these people are among those present, but in the Portuguese context, as a very significant number of young people finish their Master’s degrees and are increasingly requested to undertake survey research even during undergraduate studies, they are usually a good bet and may even persuade other family members present, like their parents, to participate.

Intuitively and according to Latané [57], it is clear that an individual is more or less influenced according to the number of people involved, their status and proximity. Thus, seeking to satisfy this aspect of status and proximity, it can also be of added value that the researcher’s presence is introduced by the event host (e.g., the owner of the winery/producer), with an introduction to the study if possible, its relevance and a call for participation. Such an introduction, indeed, had a very positive impact on recruiting several participants.

One may thus identify as a central concern the ability to spot and obtain ‘allies’ for the research project and data collection. Getting the supply agent to become an ally of the researcher in a co-constructed mission is probably one of the most facilitating aspects of the entire data collection process. Such a relationship with the supplier legitimizes and normalizes the presence of the researcher in a context in which he/she is a foreign element, decreasing the probability of his/her presence being felt as disturbing the experience. Naturally, this requires careful work on raising the awareness of suppliers in relation to the added value of the study and the return in the medium term that it may mean for the business itself.

In the case of excursions, an important ally can be the guide or the tour operator. Excursionists usually have a very controlled visit time and for that reason; even if they are interested/willing to collaborate, they cannot do so because they have to follow the group according to what is scheduled. However, they also have some “deadtime”, for example, when they move (usually by bus) between activities or queue in lines at restaurants, museums, etc. If the relationship with the guide is one of proximity, the guide him-/herself may distribute, during these “deadtimes”, the questionnaires and even send them later to the researcher, for example, by mail (as occasionally happened in the TWINE project). It is important that the researcher obtains several allies, not only because the more people collaborate in the study, the better and the faster results will be obtained, but also to diversify the sources of help, (a) avoiding bias from certain contexts (e.g., a specific type of visitor targeted by a particular tour operator) and (b) ensuring that only few may feel overwhelmed by the researcher’s requests and/or with his/her frequent presence to collect data.

4.3. Considering Alternatives to Onsite Surveys

Given that visitor numbers in rural and wine tourism are low, are there easier and possibly better ways to collect relevant data about non-massive visitor flows and tourist experiences in rural wine tourism?

Although not actually catching the same moment of the immediate experience context and, therefore, not equivalent to onsite surveys, beginning in the 1980s and 1990s, an interest was expressed in both the UK and in Canada (and perhaps elsewhere) in using conventional telephones to administer questionnaires (see examples [58,59]). Experience proved in some cases to be problematic. Many calls were necessary to locate relatively few rural tourists. Daytime weekday calls tended only to find older female respondents. Evening calls were unpopular. Calls between ca. 1600 and 1800 tended to reach large numbers of schoolchildren. Many calls were rejected because respondents felt that the caller had some form of retail aims or criminal intentions. The concept has not proved widely popular, although telephone interviewing enjoyed a recent revival due to the COVID-19 pandemic limitations on direct data collection. Still, the difficulty of contacting those who actually have a lived rural wine tourist experience in the destination studied (including national and international markets) poses substantial limits to telephone surveying where social desirability responses may be more problematic.

Another increasingly applied alternative to onsite paper-and-pencil surveys are Internet-based surveys. They are faster, easier to administer, more cost-effective, permit self-administration at any time the respondent is available, sometimes result in more answers to open-ended and sensitive questions, while showing moderate levels of success in terms of response rates, particularly in times of increasing Internet-based surveying, jeopardizing representativeness also due to high self-selection bias [60,61,62]. Even if measures may be introduced to increase response rates [62], response rates below 10% are not rare, which questions the representativeness and quality of the (highly self-selected) respondent samples. In our onsite approach, in contrast, the response rate was between 70% and 85% (assessed on certain days and hours by registration of responses over the number of attempts in specific clearly tourist-attracting survey sites), also permitting a clear identification of the niche market studied.

Last but not least, panel data from commercial companies which specialize in providing online market research services may help obtain interesting data if the sample population may actually represent the niche market under analysis, as was the case in a recent study undertaken by Bausch, Schröder, Tauber and Lane [63]. However, this approach is not cheap. Bausch et al. used a company that collects data by means of online surveys from online access panels—a group of registered Internet users who agreed to take part in market research surveys and opinion polls at certain intervals. It permitted obtaining data of a representative sample for two countries (n = 163) concerning several sociodemographic parameters. Furthermore, the company ensured that only active travellers that had taken holiday trips in the previous five years took part, ensuring well-founded opinions about tourism. The selected participants then responded to an interactive appealing and user-friendly online survey, which also permitted direct personal interaction between the research team and the participants, enhancing quality control of the reliability of data.

Still, the onsite survey methodology discussed here permits spontaneous participation of those who are in the middle of a destination visit, control of response rates, which tend to be much higher than via telephone or online, with responses directly related to the visit and the destination context. Even if responses are not always easy to obtain, the previously mentioned initiatives may help increase adherence to the study and correspondingly enhance the relevance of results.

5. Conclusions

The rural wine tourism context presents specific characteristics associated with limited numbers of visitors and niche markets, both of which bring added challenges to the implementation of quantitative studies that, as a rule, require quite large samples in order to be statistically representative and useful for certain (particularly, multivariate) statistical techniques [64]. Rural wine tourism is characterized by more personalized services, where the relationship of proximity with the producer [65] and visits in small groups are valued, surrounded by an intimate atmosphere [66] that may not be compatible with the presence of a researcher who requires completion of a questionnaire.

It is essential that researchers in this area are, on the one hand, aware of the potential difficulties in developing this type of study and, on the other hand, in possession of the necessary resources to overcome such challenges. These resources have been systematized throughout this article in four large dimensions. The first one is related to the questionnaire itself, where aspects ranging from the questionnaire layout to the formulation of its questions and instructions are addressed. The second one is related to the survey setting, where the essential situation requirements for comfortable participation, not negatively affecting the wine tourism experience, are discussed. The third dimension is related to the researcher him/herself, where aspects from image to attitude are explored, as well as the role of research assistants and team coordination. The last category of solutions refers to the phenomena of group/social influence, where some strategies are suggested to promote a positive influence on a group (and central persons within it) towards adherence to the study.

A key aspect of these recommendations, based on our research experience, is related to the valuation of time, which is increasingly important in today’s societies. Time is felt as something necessary but scarce and, therefore, most highly valued, especially leisure time with family and friends. The administration of questionnaires in a survey framework in tourism studies should respect this time as much as possible, making it worthwhile and making the participants not feel that moment as a waste of their time. Thus, it is necessary to turn the questionnaire (and its administration in a particular interaction context) into a pleasant element of the tourist experience itself through aspects previously pointed out, ranging from the researcher’s attitude, empathy and helpfulness, along with the characteristics of the questionnaire, the comfortable physical setting of questionnaire administration, leading, perhaps, to the eventual offer of rewards (e.g., a bottle of regional wine), when possible.

Another point to be highlighted is the need to align the objectives and expectations of the various elements of the research system: researchers, visitors and agents of supply. These must function as part of a single coevolving system and not as three independent, and even opposing, systems competing for time and attention. Therefore, it is essential that researchers invest time in obtaining and getting to know their “team partners” in this research path, listening to their fears (especially in the case of supply agents), their expectations, and also in observing their behavior. The researchers need to understand where they can have a respected space that enhances the tourist experience itself instead of disturbing it or being an external element to it, even if neutral, both from the point of view of the visitor and the agent of the supply.

The main limitation of this work is that it is mainly based on the authors’ experiences in the field work developed under the TWINE and several other research projects in rural tourism, mainly in Portugal and Europe [16,45,67,68] that may not be representative of other rural tourism contexts. However, given the scarcity of scientific works that fulfill the objective of informing researchers about the challenges of quantitative research and respective strategies to overcome them, particularly relevant in niche tourism contexts, such as rural wine tourism, these reflections may contribute to the development of a series of best practice measures in survey data collection, assist in better planning and executing respective field work and consequently to the production of more rigorous scientific evidence, more relevant for both the academy and praxis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C. and E.K.; methodology, D.C. and E.K.; validation, D.C. and E.K.; formal analysis, D.C. and E.K.; investigation, D.C. and E.K.; resources, E.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.C., E.K. and B.L.; writing—review and editing, D.C., E.K. and B.L.; supervision, E.K.; project administration, E.K.; funding acquisition, E.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was developed in the scope of the research project TWINE-PTDC/GES-GCE/32259/2017-POCI-01-0145-FEDER-032259 funded by the ERDF through the COMPETE 2020 Competitiveness and Internationalization Operational Programme (POCI) and national funds (OPTDC/GES-GCE/32259/2017-E) through FCT/MCTES.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and is part of the TWINE project, which was approved by FCT (PTDC/GES-GCE/32259/2017).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Weiler, B.; Hall, M. (Eds.) Special Interest Tourism; Belhaven Press: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Alant, K.; Bruwer, J. Wine tourism behaviour in the context of a motivational framework for wine regions and cellar doors. J. Wine Res. 2004, 15, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, J.; Dowling, R. Wine Tourism Marketing Issues in Australia. Int. J. Wine Mark. 1998, 10, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D. Explore Wine Tourism: Management, Development & Destinations; Cognizant Communication Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael, B.A. Understanding the wine tourism experience for winery visitors in the Niagara region, Ontario, Canada. Tour. Geogr. 2005, 7, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E.; Costa, A. O Enoturismo como factor de desenvolvimento das regiões mais desfavorecidas [Wine tourism as a factor in the development of the most disadvantaged regions]. In Proceedings of the 15th APDR Congress, Praia, Santiago Island, Cape Verde, 15 July 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kourkouridis, D. Possibilities and Opportunities of Wine Tourism Development in the Cross-Border Region of Greece-Bulgaria Through the Protection of Traditional Vine Varieties. J. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 8, 140–149. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M. Wine tourism in New Zealand. In Wine Tourism Around the World, Proceedings of the Tourism Down Under II: A Tourism Research Conference, Dunedin: New Zealand, 3–5 December 1996; Kearsley, G., Ed.; University of Otago: Dunedin, New Zealand, 1996; pp. 150–174. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, T.; Smit, B.; Jones, G.V. Toward a Conceptual Framework of Terroir Tourism: A Case Study of the Prince Edward County, Ontario Wine Region. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2014, 11, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E.; Cunha, D.; Eletxigerra, A.; Carvalho, M.; Silva, I. Exploring Wine Terroir Experiences: A Social Media Analysis. In Advances in Tourism, Technology and Systems, Proceedings of the International Conference on Tourism, Technology and Systems, ICOTTS 2020, Porto, Portugal, 29–31 October 2020; Springer: Singapore, Malaysia, 2020; Volume 209, pp. 401–420. [Google Scholar]

- Western Australian Tourism Commission/Wine Industry Association of Western Australia. Wine Tourism Strategy; Western Australian Tourism Commission/Wine Industry Association of Western Australia: Perth, Australia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd, E.T.; Canziani, B.; Hsieh, Y.C.; Debbage, K.; Sonmez, S. Wine tourism: Motivating visitors through core and supplementary services. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, P. Wine tourism development in Australia and its application to China. In China’s Tourism Development: Analysis Forecast (2001–2003); Zhang, G.R., Wei, X.A., Liu, D.Q., Eds.; Social Science Documentation Publishing House, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences: Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Getz, D.; Brown, G. Critical success factors for wine tourism regions: A demand analysis. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alebaki, M.; Iakovidou, O. Market segmentation in wine tourism: A comparison of approaches. Tourismos 2011, 6, 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Lane, B.; Kastenholz, E. Rural tourism: The evolution of practice and research approaches—Towards a new generation concept? J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 1133–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R.; Pearce, T. Tourism, marketing and sustainable development in the English national parks: The role of National Park Authorities. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 557–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, N. Novos e velhos territórios nos lazeres contemporâneos: O mundo do vinho e a importância de viagem [New and old territories in contemporary leisure: The world of wine and the importance of travel]. Cad. Geogr. 2009, 28, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, R.; Hall, C.M.; Mclntosh, A. Wine tourism and consumer behaviour. In Wine Tourism Around the World: Development, Management and Markets; Hall, C.M., Sharples, L., Cambourne, B., Macionis, N., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Vagionis, N. Alternative Tourism in Bulgaria: Diversification and Sustainability; OECD: Paris, France, 2008; pp. 29–46. Available online: https://www1.oecd.org/cfe/tourism/40239624.pdf.no (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Finn, M.; Walton, M.; Elliott-White, M. Tourism Leisure Research Methods: Data Collection, Analysis and Interpretation. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 285. [Google Scholar]

- Eusébio, C.; Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J. A relevância da investigação no ensino do turismo: Algumas estratégias de intervenção na realização de inquéritos [Research research in tourism education: Some strategies for carrying out surveys]. In Proceedings of the 3as Jornadas Ibéricas do Turismo, Coimbra, Portugal, 1–3 May 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Garner, M.; Wagner, C.; Kawulich, B. Teaching Research Methods in the Social Sciences; Ashgate Publishing Ltd.: Farnham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- DeMarrais, K.; Lapan, S.D. Foundations for Research: Methods of Inquiry in Education and the Social Sciences; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Dolnicar, S. A review of data-driven market segmentation in tourism. J. Travel Tourism. Mark. 2002, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frochot, I. A benefit segmentation of tourists in rural areas: A Scottish perspective. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E.; Eusébio, C.; Carneiro, M.J. Segmenting the rural tourist market by sustainable travel behaviour: Insights from village visitors in Portugal. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 10, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, J.; Eusébio, C.; Kastenholz, E. Expenditure-Based Segmentation of a Mountain Destination Tourist Market. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2012, 29, 695–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesonen, J.A. Targeting Rural Tourists in the Internet: Comparing Travel Motivation and Activity-Based Segments. J. Travel Mark. 2015, 32, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, S.; Duarte, P. An integrative model of consumers’ intentions to purchase travel online. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, H.; Campón-Cerro, A.M.; Hernández-Mogollón, J.M. Enhancing rural destinations’ loyalty through relationship quality. Span. J. Mark. 2019, 23, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kastenholz, E.; Eusébio, C.; Carneiro, M.J. Studying factors influencing repeat visitation of cultural tourists. J. Vacat. Mark. 2013, 19, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kyle, G.; Scott, D. The Mediating Effect of Place Attachment on the Relationship between Festival Satisfaction and Loyalty to the Festival Hosting Destination. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 754–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J.; Marques, C.P.; Loureiro, S.M.C. The dimensions of rural tourism experience: Impacts on arousal, memory, and satisfaction. J. Travel Mark. 2017, 35, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, J.; Alant, K. The hedonic nature of wine tourism consumption: An experiential view. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2009, 21, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zatori, A.; Smith, M.K.; Puczko, L. Experience-involvement, memorability and authenticity: The service provider’s effect on tourist experience. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E.; Eusébio, C.; Carneiro, M.J. Purchase of local products within the rural tourist experience context. Tour. Econ. 2016, 22, 729–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E. Analysing determinants of visitor spending for the rural tourist market in North Portugal. Tour. Econ. 2005, 11, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, M.; Saayman, M.; Ellis, S. Determinants of visitor spending: An evaluation of participants and spectators at the Two Oceans Marathon. Tour. Econ. 2012, 18, 1203–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sæthórsdóttir, A.D. Managing popularity: Changes in tourist attitudes in a wilderness destination. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 7, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E. The Role and Marketing Implications of Destination Images on Tourist Behavior: The Case of Northern Portugal. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moswete, N.N.; Darley, W.K. Tourism survey research in sub-Saharan Africa: Problems and challenges. Curr. Issues Tour. 2012, 15, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, L.; Ascensão, M.; Charters, S. Wine Routes in Portugal: A Case Study of the Bairrada Wine Route. J. Wine Res. 2004, 15, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barroco, C.; Amaro, S. Examining the progress of the Dão wine route wineries’ websites. J. Tour. Dev. 2020, 33, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, D.; Carneiro, M.J.; Kastenholz, E. ‘Velho Mundo’ versus ‘Novo Mundo’: Diferentes perfis e comportamento de viagem do enoturista? [Old world versus new world—Wine tourism—Diverse traveller profiles and behaviours?]. Rev. Tur. Desenvolv. 2020, 34, 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Macionis, N.; Cambourne, B. Wine tourism: Just what is it all about? Wine Ind. J. 1998, 13, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Burningham, K. Using the language of NIMBY: A topic for research, not an activity for researchers. Local Environ. 2000, 5, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahlqvist, S.; Song, Y.; Bull, F.; Adams, E.; Preston, J.; Ogilvie, D. Effect of questionnaire length, personalisation and reminder type on response rate to a complex postal survey: Randomised controlled trial. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Singh, R.; Mangat, N.S. Elements of Survey Sampling; E-Book, 15, 3; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rolstad, S.; Adler, J.; Rydén, A. Response burden and questionnaire length: Is shorter better? A review and meta-analysis. Value Health 2011, 14, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Creswell, J. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, D. Business Research for Decision Making, 6th ed.; Brooks-Cole Thomson Learning: Belmont, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, D.; Twenge, J. Social Psychology, 13th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gouveia, R. Processos de influência social [Social Influence Processes]. In Psicologia Social: Temas e Teorias; Camino, L., Torres, A.R.R., Lima, M.E.O., Pereira, M.E., Eds.; Technopolitik: Brasília, Brasil, 2013; pp. 241–266. [Google Scholar]

- Sherif, M. A study of some social factors. Arch. Psychol. 1935, 187, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Asch, S.E. Social Psychology; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Latané, B.; Wolf, S. The social impact of majorities and minorities. Psychol. Rev. 1981, 88, 438–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.; Sue Broad, S.; Weiler, B. A Closer Examination of the Impact of Zoo Visits on Visitor Behaviour. J. Sustain. Tour. 2008, 16, 544–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatipoglu, B.; Ertuna, B.; Salman, D. Small-sized tourism projects in rural areas: The compounding effects on societal wellbeing. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Best, S.J.; Krueger, B.; Hubbard, C.; Smith, A. An assessment of the generalizability of Internet surveys. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2001, 19, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B. Online Travel Surveys and Response Patterns. J. Travel Res. 2009, 49, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Woodside, A.G.; Meng, F. How Contextual Cues Impact Response and Conversion Rates of Online Surveys. J. Travel Res. 2014, 53, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bausch, T.; Schröder, T.; Tauber, V.; Lane, B. Sustainable Tourism: The Elephant in the Room. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.J.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis Global Edition, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bruwer, J.; Rueger-Muck, E. Wine tourism and hedonic experience: A motivation-based experiential view. J. Hosp. Res. 2019, 19, 488–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidali, K.L.; Kastenholz, E.; Bianchi, R. Food tourism, niche markets and products in rural tourism: Combining the intimacy model and the experience economy as a rural development strategy. J. Sustain. Res. 2013, 23, 1179–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Kastenholz, E.; Carneiro, M.J.; Eusébio, C. Diverse socializing patterns in rural tourist experiences: A segmentation analysis. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 401–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B.; Weston, R.; Davies, N.; Kastenholz, E.; Lima, J.; Majewski, J. Industrial Heritage and Agri/Rural Tourism in Europe: A Review of Their Development, Socio-Economic Systems and Future Policy Issues; European Parliament Committee on Transport and Tourism: Brussels, Belgium, 2013; Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/etudes/join/2013/495840/IPOL-TRAN_ET(2013)495840_EN.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).