Abstract

Good sustainability decisions depend on how companies respond to wide-ranging exposure to exogenous and endogenous pressures. The purpose of the article was to determine whether companies in different industries respond differently to stakeholders’ pressures when prioritising Environmental, Social and Governance sustainability performance (ESG-SP) activities. Data of six sectors, with a total of 75 companies was extracted from the CSRHub database, which is a rating agency that focuses on assessing ESG performance of companies. The ANOVA, pairwise comparative and multiple comparison Tukey HSD tests were applied to compare mean scores across the sectors. Overall industry scores show no evidence of ESG-SP differences across industries in the sectors examined. It was however revealed that three (3) out of twelve ESG ratings have significant differences namely: Community Development and Philanthropy; Human Rights and Supply Chain; as well as Compensation and Benefits. The study found that the type of industry does not have a significant role in determining the ESG rating of a company. Future studies can look at a longitudinal analysis to shed light on the pattern of sustainability practices across companies that are listed on the JSE.

1. Introduction

Despite ongoing academic debates on the determinants of Environmental, Social and Governance Sustainability Performance (ESG-SP), it remains uncertain whether the industry to which a company belongs is a significant factor that influences decisions about companies’ ESG activities. When companies align their ESG-SP decisions to legitimate stakeholder’s interests, they simultaneously maximise shared value which is fundamental to their existence.

The Brundtland commission defined sustainable development as the “human ability to make development sustainable to ensure that it meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [1]. Sustainable development is both a moral and ethical matter which goes beyond drivers of economic, environmental and social aspects [2]. It may, therefore, be reasonable to expect that companies as global citizens should contribute towards sustainable development in response to societal bounds, norms and stakeholder expectations. As a result, companies need to embed sustainability into their business operations to show their commitment to the sustainable development agenda [3].

Sustainability therefore not only contributes to the achievements of the sustainable Development goals (SDGs) but also provides steady financial benefits [4]. Essentially companies that are morally prioritising sustainability initiatives and stakeholders’ claims do so on the basis of moral and economic groundings that inform business decisions regarding who should benefit from sustainability-related actions [5].

The article is structured as follows: In Section 2 the article focuses on a literature review of the environmental, social and governance (ESG) concept; sustainability reporting (SR) and its evil twin; ESG and different industries; the theoretical lens of the study; the case for regulatory mechanisms and the context of the study, namely the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) listing requirements. Section 3 deals with the hypothesis development, followed by the methodology in Section 4. The research results are presented in Section 5 and lastly conclusions and recommendations are presented in Section 5 and Section 6, respectively.

2. Literature Review

There is a growing call for companies’ sustainability reports to reflect sector-specific ESG indicators [6,7,8,9,10]. A sustainability report is a report published by companies to report the impact of their daily operational activities in economic, social, and environmental terms, also highlighting the link between companies’ values, strategies, and governance models with their commitment towards sustainable development [11]. SR in this regard refers to companies’ communication of its ESG practices to its stakeholders in line with its commitment toward sustainable development. In the same vein, SP in this study is defined as companies’ observable outcomes and tangible progress with respect to ESG activities aimed towards the achievement of the SDGs while improving the quality of life of employees, local communities and society at large with due care for the environment [12].

2.1. The Environmental, Social and Governance Concept

The environmental, social and governance (ESG) concept is an amalgamation of three distinct disciplines which may overlap with issues in one discipline typically impacting on or being impacted by elements of the other two [13]. ESG has become a must-have goal for sustainability [14]. The increasing demand for sustainability has pressured companies to disclose sustainability information about their ESG activities. Companies have optimally integrated sustainable development into their business model, and this is viewed as being more ethical and conscious. Such companies are likely to relate better with environmentally engaged citizens and loyal customers who are also concerned about the environment, health and well-being of their communities [15].

On the one hand, ESG is being recognised as financially material, especially for highly diversified investors [16]. Consequently, companies are disclosing material ESG information, even though the specific information that is material may vary across companies and industries [16]. To this end, ESG has been instrumental in successfully incorporating sustainability into the financial mainstream as listed companies are increasingly ESG-rated [17,18]. Investors are factoring ESG screening into decision-making processes and they are bringing their sustainability lens to their investment analysis [18].

There is emerging evidence that ESG contributes to the long-term financial performance of a company [19,20,21]. This means that if a company wants to focus on long-term profits, practicing pro-ESG actions would reduce risks and increase future profitability. While a good balance between sustainability performance (SP) and SR is important, companies that improve both their ESG performance and disclosure stand to increase financial performance, though ESG performance is more critical in future profitability (the long-term) while ESG disclosure is more important for profits (short-term) [20]. Companies that report high ESG performance are likely to experience more resilience during both normal and turbulent times [21].

2.2. The Role of Sustainability Reporting and Consequent Greenwashing

The demand for sustainability reporting (SR) reform has risen significantly and is mainly being driven by a growing consensus between mainstream investors who are beginning to connect sustainability to financial performance. While some companies may have adopted the motto ‘do good and talk about it’, sceptics have criticised this stance pointing to reporting-performance portrayal gaps [22]. In some instances, sustainability reports have been dubbed “fairy tales” as companies fail to ‘walk their talk’ [22]. Moreover, some companies have been accused of greenwashing tendencies and as a result they are under increasing pressure to ‘do good’ beyond regulatory obligations and for more than financial benefits [4]. Unfortunately, SR of which ESG is a subset has been seen as a tool to facilitate greenwashing. ESG is also used strategically to maintain, defend or repair societal legitimacy [23]. However, companies are striving to prioritise stakeholder demands regarding material aspects of ESG as a form of accountability to maintain a societal license to operate [22].

According to [24], the impact of ESG disclosure on profitability, performance, and value cannot be ignored. Reference [24] immediately cautions that perceived/potential greenwashing behaviour decreases perceived value. In fact, [24] further states that greenwashing scandals have had serious consequences for companies ranging from the loss of trust and loyalty from consumers, shareholders, socially conscious investors, consumers’ attitudes towards the company leading to revolt against the company.

Nevertheless, in their attempt to address pressure from stakeholders, some unethical managers may tend to resort to using SR as a legitimacy tool to justify a company’s continued existence in society by greenwashing. Greenwashing is a phenomenon that emerged as sustainability’s ‘evil twin’ [25]. The increasing prevalence of the greenwashing phenomenon casts doubt and scepticism on bona fide sustainability policies thereby undermining the very essence of sustainable development [25].

2.3. ESG and Different Industries

References [26,27,28] argue that industries/sectors should be responsive to pressures from the local society concerning their license to operate [29]. Therefore, ESG ratings of industries within the context of a highly regulated setting at the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) are compared to examine if companies respond to sector-specific sustainability aspects of ESG [30]. Companies on the JSE may have demonstrated how they have managed to imbed ESG into their operations by aligning their business models with sustainable development.

However, some industries face more public scrutiny than others because of more stakeholder pressures and demand for more transparency and compliance [6]. In fact, “companies from different industries have different priorities for different stakeholders” [31] (p.5). This article contributes to the body of knowledge by assessing a renewed analysis of ESG data to determine if companies in different industries respond differently to prioritising ESG-SP activities.

References [32,33] pointed out that progressive companies adopt a multi-fiduciary posture by incorporating what stakeholders indicated as a priority in their ESG report to account for diverse stakeholders’ needs and interest [34,35]. Companies in dirty industries such as mining and energy are likely to improve sustainability benchmarks and create a win-win model for business and society by addressing environmental and social concerns in ways that increase profitability [36].

Industry characteristics determine the weights that companies apportion to ESG and this is attributable to the relative importance of ESG factors which vary by sector due to the specificities of the industries [14]. Reference [14] posits that while governance issues are generally sector-neutral, social and environment factors are highly sector-relevant. Furthermore, [14] indicates that ESG weights are varied not only by the industry but also by countries with different environmental, economic, geographic, and political characteristics. According to [14], current ESG factors do not necessarily take into account country-specific and/or industry-specific management environments [14]. It is therefore worthwhile to study the ESG criteria based on industrial differences. According to [14], materiality is different for each country, industry, and company but companies that focus on industry-specific materiality issues have been shown to perform better. While there are sector- and county-specific contextual determinants of ESG they are also largely dependent on national context or history, culture and tradition, as well as factors such as governance gaps, political reform, and socioeconomic priorities [37]. Moreover, [37] indicates that powerful external drivers such as regional and global governance must be taken into consideration. Reference [37] found that while individualised sector-specific prioritised ESG indicators showed that the environmental domain was common; corporate governance appeared the primary focus while the social domain which perhaps reflect the effect of country- and sector-specific needs, was the most variable in Saudi Arabia private-health sector.

Therefore, the content and focus for ESG disclosures are different from one sector to another [38]. According to [38], ESG reports need to cater to stakeholders’ needs based on solid materiality matrices relevant for the company and industry in which it operates. Reference [38] alludes that significant differences with respect to companies’ ESG disclosure are due to different social contexts, country classifications and their stakeholders whereby companies in riskier sectors may use ESG disclosure as a way to show responsibility [37]. This is in line with [39]’s assertions that ESG priorities vary by sector in a sense that capital-intensive industries such as coal, oil, natural gas, and chemical are more exposed to environmental problems than labour-intensive industries such as retailing which are more inclined to social problems associated with human rights issues and compliance with international labour standards [39].

Reference [7] indicated that ESG reporting is strongly correlated to the sector in which a company operates. This means that a set of common rules for companies that operate in different sectors may be required as companies are impacted differently by external sectorial events as well as negative effects connected to the sector [40].

Since the materiality of specific ESG factors varies by industry sector, the sector-specific nature of ESG materiality warrants for supplementary ESG disclosures with sector-specific information [41]. In the same vein, core mandatory disclosures should be supplemented with more flexible, principles-based approaches [41].According to [41] ESG screening criteria have increased remarkably over time and ESG investing is now associated with a reduction of stakeholder risk. As a consequence, high ESG ranked funds have less overlap with all other funds than low ESG ranked funds. Reference [41] found evidence that the relative market value loss of the High ESG ranked funds is lower than the loss experienced by the Low ESG ranked counterparts in the time span with lower volatility [41].

On the other hand, [40] examined the role of ESG performance during the market-wide financial crisis, triggered in response to the COVID-19 global pandemic. A combination of core indicators common to all companies, and sector-specific indicators were used to form ESG scores. The study found that among the three dimensions of ESG, governance (G) is the most important, whereas the importance of environmental (E) and social (S) risks vary by sector. Furthermore, high-ESG portfolios remain consistently higher than that of the low ESG group and that high-ESG portfolios generally outperform low-ESG portfolios [40]. Reference [42] supports the notion that ESG scores need to be tailored to reflect data that is relevant to its industry sector.

Reference [43] performed a sector analysis of the 12 sectors represented on the US Dow 30 Index according to their entropy contribution in each of the ESG pillars, relative to each other. The relative performance of each sector to the average sector performance was analysed to determine which sectors communicate ESG well, and which sectors distort the information content of the corresponding ESG measure. The study found that the healthcare, defence, and automotive sectors are conveying unclear messaging within the environmental and social pillar, while the financial, consumer goods, and industrial sectors convey messages very efficiently in these pillars [43]. Another key finding was that sectors with clear, lean, and flexible governance structures, such as automotive, IT, and travel, are most effective in messaging [43].

Referene [31] analysed ESG indicators of 52 companies in the logistics sector worldwide. The results show that the sector does not agree on the materiality of sustainability indicators. Contrary to prior research that found the tendency of companies in the same industry showing compatible patterns in SR, and differences in materiality of sustainability indicators across industries, Reference [31] found that more than 70% of the indicators, do not exhibit compatible patterns of what logistics companies value as material sustainability indicators. According to [31] developing sector-specific guidelines on sustainability indicators could enhance clarity and stimulate compatible reporting patterns with regard to material sustainability indicators.

Reference [14] developed an ESG framework specific to South Korea which is regarded as an emerging country by international rating agencies where ESG is also considered as well-managed. The study therefore factored amongst others; country-specificities such as the level of ESG investment whereby the results show that institutional investors place more importance on environmental and governance factors compared to social factors. According to [14] ESG weightings should be varied not only by the industry and rating providers but also by countries with different environmental, economic, geographic, and political characteristics [14].

It is clear that industry effects in ESG reporting requires an industry-sensitive approach to sustainability and that further standardisation may be necessary to level the playing field whilst at the same time considering the sectorial nature of companies’ operations [44]. Although cross-industry studies may produce results that are generalizable to associated industries, sector-specific studies allow inferences relevant for advancing sector-specific matters [45]. As such, companies in a specific industry may have greater justification for ESG practices than others and therefore are keener to report the outcomes thereof. Reference [6] emphasises the importance of sector-customised metrics because such metrics allow companies to track and measure progress. Sector-specific ESG disclosure requirements may be used to supplement standard disclosure items [45].

2.4. The Theoretical Lens

Theories that can be used as lenses for SP include corporate social responsibility (CSR), and the stakeholder, legitimacy, organisational and agency theories. This study draws upon the stakeholder theory to conceptualise this research because of its applicability and richness [46]. Although stakeholder theory has been widely critiqued, it remains fundamental to understand business and societal relationships and is the most commonly used theoretical framework to evaluate CSR [47]. Stakeholder theory has been used previously to analyse SP because of shared ideologies with sustainability [48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56]. The influence of stakeholder theory in managing sustainability issues has been widely researched in the literature [57,58,59,60,61,62]. The ethics of stakeholder theory as an arbitrator cannot be ignored any further if business is to maintain its social license to operate (SLO). There is empirical evidence that illustrate that SP facilitates stakeholder engagements, thereby promoting more positive dialogue with stakeholders [63].

2.5. A Case for Regulatory Mechanisms

Empirical studies show that the drive by companies to portray high SP to their stakeholders and regulatory authorities may facilitate greenwashing through manipulation of organisational sustainability data, defiance or avoidance responses to disguise externalities and poor SP [64,65,66,67,68,69,70]. The greenwashing concept is an umbrella term used to characterise superficial and misleading sustainability information [71]. However, there are scholars who consider greenwashing for only environmental issues, distinguishing it from the term ‘blue-washing’ which normally stands for social or human rights issues, or ‘pinkwashing’ for health issues for example breast cancer). Other researchers consider greenwashing a social and environmental phenomenon [72].

Greenwashing here is an expansive term which refers to activities by companies aimed to conceal negative externalities and questionable corporate practices through unsubstantiated self-laudatory claims which are misleading [73]. Stakeholders can be deceived by sweeping sustainability claims which may not be easy to discern whether a company is making untruthful claims or not [74]. This points to the growing pressure on policymakers to fill the regulatory vacuum through mandatory disclosures and performance [75,76]. Regrettably, the vacuum created a breeding ground for greenwashing which is also perpetuated by a lack of consensus on the measurement of SP. Reference [77] attributes this vacuum to the ineffectiveness of mandatory performance and lack of universal standards and frameworks.

Reference [78] found that both concealment and attribution are strategies adopted by manipulative companies to sway the impressions of stakeholders by overstating good news to gain legitimacy. Reference [78] further explained that concealment may involve obscuring or masking negative externalities and outcomes using corporate rhetoric to persuade stakeholders in a company’s favour, therefore deliberately confusing them with information asymmetry.

2.6. The Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) Listing Requirements

The JSE is the first stock exchange worldwide to introduce a sustainability index measuring companies on sustainability indicators related to ESG practices. The South African experience demonstrates that integrated reporting is not just an academic exercise [79]. This makes South Africa the most suitable setting for ESG research [80]. It can be argued that the concept of sustainability and sustainable development finds more resonance in the South African context and that the FTSE/RI Index companies are indeed championing sustainable business practices.

Moreover, stakeholders are incorporating ESG considerations into their benchmarks and investment decisions. The increasing demand for ESG information has been notable as investors want to implement ESG investment strategies, and therefore, the JSE utilises FTSE Russell’s ESG Ratings and data model tools. The data model is customised to cater for companies’ needs with clear definitions and rules for assessing ESG practices.

The model determines the overall rating which is broken down into three (3) underlying pillars namely: environmental, social and governance. Over 300 indicators are individually researched to cater for ESG aspects focusing on key operational issues.

The FTSE Russell’s ESG Ratings and data model is made up of 14 themes viz: biodiversity; climate change; pollution and resources; water security; supply chain: environmental; customer responsibility; health and safety; human rights and community; labour standards; supply chain: social; anti-corruption; corporate governance; risk management; and tax transparency [81]. The themes are aligned with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and each theme contains about 10 to 35 indicators. An average of 125 indicators are applied per company taking account each company’s unique circumstances and operational issues. The indicators are used to produce a theme score [81].

Based on the theme indicators, the model allocates a theme score and a theme exposure for each of the 14 themes, following which a cumulative pillar score and cumulative pillar exposure is allocated for each of the three ESGs. Thereafter, a cumulative calculation of the total ESG performance is allocated to produce a company’s ESG rating.

The FTSE/JSE RI Index has been designed to identify South African companies with leading ESG practices. To meet eligibility for FTSE/JSE RI Indices, companies should score a minimum inclusion criteria of a 2.5 overall ESG Rating [81]. Constituents of the FTSE/JSE RII with an ESG Rating below 2.4 are at risk of removal from the index.

Furthermore, companies listed on the JSE should adhere to King IV™ Governance Code which became mandatory in 2017 [82]. The JSE amended its listing requirements in May 2017 after the Institute of Directors in Southern Africa (IoDSA) released the final version of King IV™. Under the amendments, listed companies do not have the choice that non-listed companies have—the choice to apply only some of the King Code principles and explain the ones they have not applied. Listed companies must apply all the latest King Code principles.

3. Hypothesis Development and Testing

The industry in which companies operate is also an important driver to influence decisions about which ESG activities to undertake [83]. SR was found to be strongly correlated to the type of sector [7]. This is due to the different levels of exposure to pressures from society, stakeholder groups, existing and prospective regulations [9]. Industry affiliation determines SP of companies [84] and plays a significant effect especially with reference to the environmental dimension [84,85,86]. Environmentally sensitive industries exhibit higher levels of environmental disclosure. This is especially true for energy, utilities, industrials and materials or resources companies [64]. These industries are susceptible to much more stringent regulations and are therefore expected to marshal considerable resources into environmental sustainability issues.

Moreover, some studies [83,87] revealed that studies in developed countries’ industry have a strong and positive relationship with sustainability disclosure. Reference [88] indicated that the industry sector has a significant effect on environmental performance. It is assumed that companies operating in the same industry may adopt similar patterns regarding the sustainability information they publish [31,89]. Whilst there could be both similarities and differences in sustainability reports of companies, this may be attributed to industry-level pressures, leading to homogeneity in their strategies [90]. As a result, it should be expected that there would be compatible patterns of what is deemed material ESG indicators [31]. However, other company-level characteristics such as board size and diversity also play a significant role in the determination of materiality disclosure [32].

Reference [7] found that there was an increase in SR by companies operating in controversial environments such as basic materials and that industries that were less inclined to CSR are those that were previously characterised by lower levels of SR. There is evidence that sustainability ratings remain a challenge for the financial sector, however there is still much space for improvement through its lending and investing [91].

According to [92] the financial sector contributes to sustainability both positively and negatively. Reference [93] argues that companies affiliated in sustainability-sensitive industries are more likely to disclose environmental information whereas companies operating in the financial sector revealed a statistically significant negative effect. Therefore, there is a need to identify sector-specific ESG indicators that take sectorial risks and vulnerabilities into account [8,9]. Reference [9] asserts that sustainability topics that are most likely to influence future risk and financial performance of companies vary across different industries.

Referenece [94] conducted a seven year period multi-sector longitudinal study on the reliability of assurance statements and their contribution to stakeholder accountability and found that although sector-specific specificities were observed, the main findings were that they do not appear to differ significantly between the sectors. Reference [94] found that industry plays a significant role in the determination of materiality disclosure. The following hypotheses are proposed based on the above discussion.

Null Hypothesis:

There are no significant differences between ESG ratings of different industries.

Alternate Hypothesis:

There are significant differences between ESG ratings of different industries.

4. Materials and Methods

The research design is a quantitative inquiry that involves statistical procedures for the data analysis and interpretation of the research results. Purposive sampling allowed the researchers to decide on the companies that fit the purpose of the study and to position it in the context of sustainability. Therefore, future researchers should exercise utmost caution when extrapolating results to other companies that are not constituents of the FTSE/JSE RI Index and should be mindful of the extent to which they can confidently extrapolate the results to a wider population.

Quantitative data from six sectors, with a total of 75 companies were collected and analysed. The time horizon of the study is confined to the 2017 financial year to capture revised JSE listing requirements announced in May 2017 after the King IV™ comply or explain principle. All companies assessed are subscribers to FTSE/JSE RI Index. the analysis of variance (ANOVA), multiple comparison Tukey HSD test and matched-pairs differences were used to test the research hypothesis and to understand whether SP vary across sectors. Therefore, the pairwise comparison method was conducted to compare SP between industries.

According to [95] industry and some company-level characteristics determine materiality of SR disclosures. The study therefore applied content analysis to extract SP data of 75 companies drawn from different industries. These companies were active on the FTSE/JSE RI Index and were captured independently by a rating Agency called the CSRHub. The CSRHub ESG ratings have been used previously in academic research [96]. The CSRHub ESG rating agency is a B Corporation which is also an organisational stakeholder with the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), a silver partner with Carbon Performance Project (CDP). The CSRHub is a founding member of The Alliance of Trustworthy Business Experts (ATBE) and supports both the Global Initiative for Sustainability Ratings (GISR) and the International Integrated Reporting Committee (IIRC) [97]. The CSRHub has a comprehensive information aggregation tool with transparent ratings and rankings of 22,318+ companies from 135+ industries in 148+ countries. The CSRHub has the largest contribution of data coming from leading ESG data sources [97]. The CSRHub’s overall ratings are based on four categories: environment, employees, community and governance, comprised of twelve different sustainability areas.

The CSRHub is a web-based tool that provides public access to ESG ratings. The CSRHub’s ratings and metrics are drawn from more than 370 sustainability data sources. To compute the ESG ratings the CSRHub uses sustainability information from its data sources. Each source’s information is analysed with a software which converts data into a 0 to 100 score (zero is worst, 100 is best). Data is then weighted and normalised across all companies to remove bias and to create a more consistent rating. This data is further mapped into one of twelve different sustainability areas and processed to produce ratings. The CSRHub is widely used in academic research.

The qualifying criterion for the content analysis is that a company should fall under the FTSE/JSE RI Index. The unit of analysis is individual CSRHub reports of the FTSE/JSE RI Index. The study focuses on data collection from six independent sectors, namely basic materials, consumer goods, financials, health care, industrial and technology (Appendix A: Table A1). The CSRhub dimensions scores (community, employees, environment, and governance) were validated using exploratory factor analysis (EFA), and varimax rotation confirmed all four dimensions [96].

Sustainability data allow the study to compare the sustainability practices of companies across industries. The CSRHub data enables comparison of company-specific sustainability ratings with peer companies, industries and other companies across the globe [96]. Although the paper articulates the origins of the JSERI Index and how it is computed from the individual company scores, the JSE RI Index is not the subject of analysis. Each company falls into one of the six sectors and the composite index was not used. This ensured that the datasets were independent, and the means were therefore compared across the sectors.

5. Presentation of Results

This section of the study is structured into two (2) sub-sections as follows: Section 5.1 presents the frequency distribution of companies from six (6) sectors that informed the study. Section 5.2 presents the industry analysis and discussions of results.

5.1. Frequency Distribution by Industry

A total of six sectors, made up of 75 public companies listed on the FTSE/JSE RI were selected for this study. The data from the content analysis were analysed using IBM-SPSS 27 (company, city, state abbreviation if USA, country). The population and sampling of the study is summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Frequency counts of companies that participated in the survey.

Table 1 presents the frequency distribution of companies by industry. The majority (29%) of the companies fall under the financial sector, followed by basic metals (28%) and thereafter consumer goods (23%). It is also clear that companies belonging to the industrials; health care; and technology sectors represent 9% and 5% of the index, respectively.

Table 2 depicts the CSRHub validated variables that will be used to measure the SP of the index. Full details of the CSRHub constructs are shown in Appendix A.

Table 2.

List of the CSRHub validated constructs.

5.2. Industry Analysis and Discussions

The purpose of this section is to present industry descriptive statistics and the ANOVA, which mainly focusses on the understanding of the sample under observation. Sustainability performance data of the FTSE/JSE RI Index was sourced from the CSRHub. Data was compiled in Microsoft Office Excel and further analysed through various statistical methods. Sustainability ratings are presented quantitatively based on the CSRhub rating methodology where zero is regarded as worst SP, and 100 best. The higher the rating the better the SP. The analysis was carried out in IBM SPSS Statistics 21. Table 3 depicts an overview of the CSRhub rating by industry.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics by industry (N = 75).

The CSRhub rating is used as an indicator of perceived SP. Table 3 shows that companies affiliated with industrials scoring the highest mean of 56.6, whilst companies under technology scored the lowest mean of 54.7. This may be attributable to sector-specific environmental issues which have limited relevance to low environmental-impact industries such as technology [98] due to diverse contexts across reporting industries. According to [86], companies operating in sensitive industries (industrials) tend to produce more environmental performance information in their reports. Such companies are susceptible to stringent regulations as they are highly likely to cause further environmental damage [99,100]. Reference [101] also found a link between sector affiliations and the degree of SR citing that industry type was found statistically significant in explaining the extent of social disclosure. Financials and health care would be linked with low reporting, whilst basic materials and industrials are associated with high reporting. This agrees with [85] who found that industry membership influences the adoption of integrated reporting. According to [102], companies from high social and environmental impacts need to engage more extensively in SR in order to respond to sector-specific stakeholder pressures. A one-way ANOVA was conducted for the Index’s CSRHUB score to test whether there are any significant differences among the means of the Index scores for the various industries. Table 4 presents the one-way ANOVA by industry.

Table 4.

One-way ANOVA by industry.

Table 4 illustrates that there are no statistically significant differences between the mean SP from one industry with another at 95.05% confidence level with the F-ratio equal to 0.1668, and a p-value > 0.05 (0.9739) failing to reject the null hypothesis. In other words, the null hypothesis that there is no statistically significant difference in ESG ratings for different industries could be accepted. The null hypothesis was retained concluding that there is no evidence that ESG ratings vary between industries in the population examined. Consistent with [100], the results of our analysis did not reveal any significant differences between sectors.

The researchers further investigated ESG scores that make up ESG ratings using a one-way ANOVA test. The parametric F-test will indicate whether there is a statistical difference between the means. In the next section, the study considers individual scores with a focus on those that show significant differences (Table 5).

Table 5.

One-way ANOVA for individual scores by industry.

Table 5 shows that individual scores for community development and philanthropy (IC1) returns an F-statistic of 25.5 with a p-value of <0.0001 *, human rights and benefits (IC3); returns a F-statistic of 5.5 and a p-value of 0.0002 * and compensation and benefits (IE1) returns a F-statistics of 4.6 with a p-value of 0.0011 *. Individual scores show statistically significant differences when compared across industries. Since the p-values for individual scores are too small (≤0.05), there is substantial evidence against the null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is therefore rejected, and the alternative hypothesis accepted. The results are consistent with [64,83,84,87,88,90,101,102].

A further analysis to investigate individual differences with respect to ESG indicators was conducted to avoid a possible Type 1 error. The purpose of using other tests was to ascertain the conclusion on whether to reject or accept the null hypothesis. The overall score is 55.3 and this was aggregated using the industry CSRHub scores’ average for companies belonging to respective industries. The authors investigated discrepancies between company and overall ESG scores focusing on deviations between specific industries. A parametric test was used to drill down to individual ESG indicators by industry.

In this section the study only focuses on the differences between individual ESG scores and how they are related to the overall ESG score of 55.3. The multiple comparison Tukey HSD tests were used to identify differences between the As and the Bs. In this test, industries that are not connected by the same letter are significantly different. The multiple comparison Tukey HSD tests revealed that three (3) out of twelve ESG indicators have significant differences namely: IC1: (<0.0001 *), IC3 (0.0002 *) and IE1 (0.0011 *). The HSD test results are displayed in Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8 to compare differences between letters, that is, As and Bs by industry.

Table 6.

IC1 Connecting letters report by industry.

Table 7.

IC3 Connecting letters report by industry.

Table 8.

IE1 Connecting letters report by industry.

5.2.1. Community Development and Philanthropy (IC1)

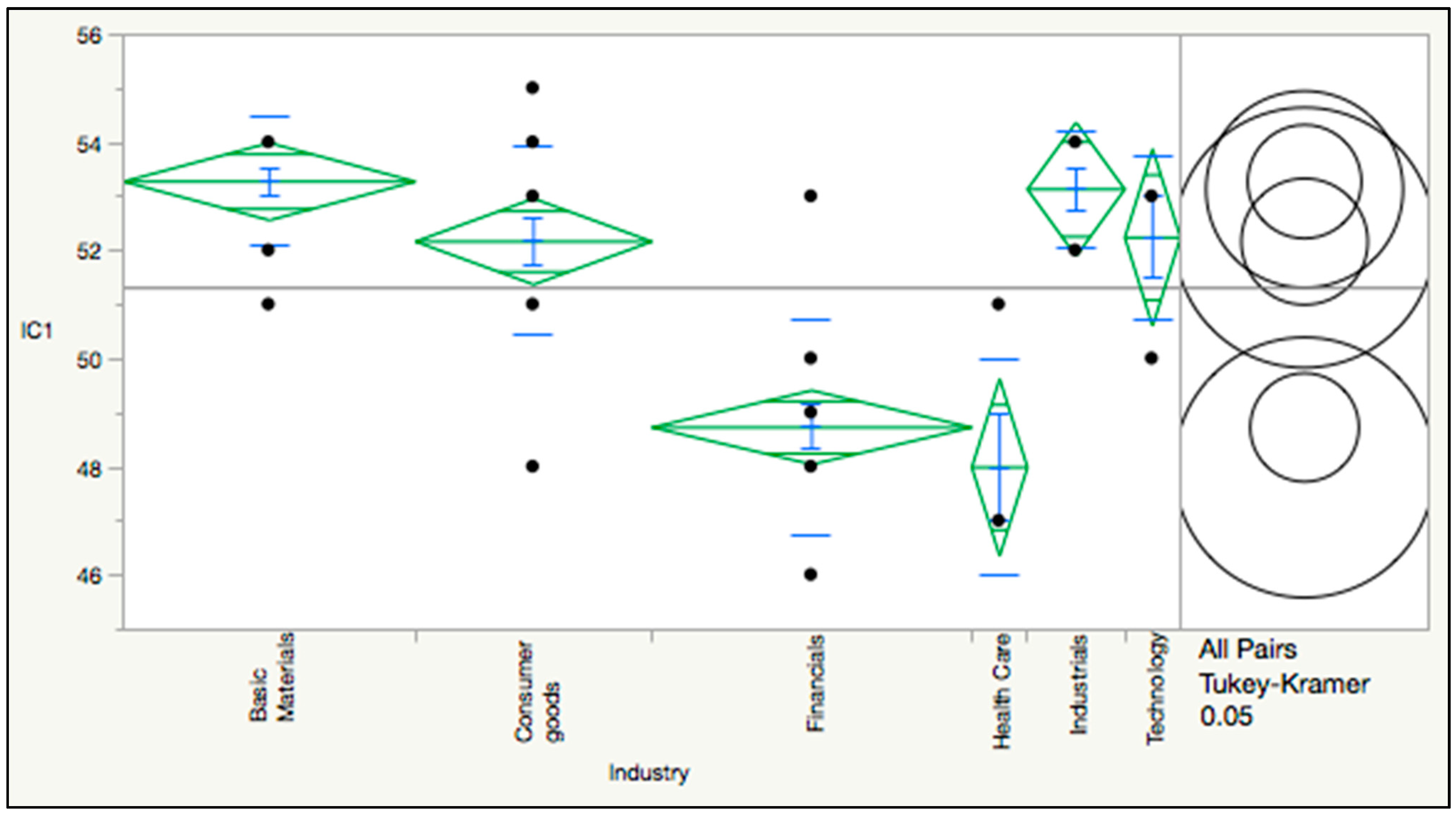

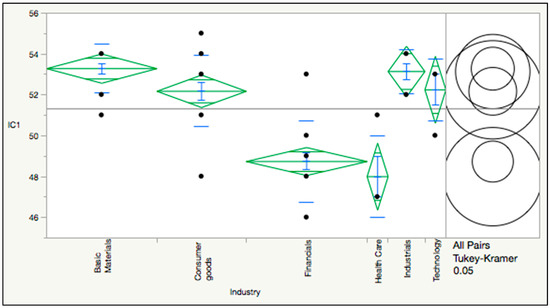

In Table 6 and Figure 1 it was investigated whether IC1 shows differences between individual ESG scores and the overall industry score.

Figure 1.

One-way ANOVA of IC1 by industry.

The multiple comparison Tukey HSD tests in Table 6 and Figure 1 revealed that on the community development and philanthropy variable, financials and health Care (the two lowest means) differ significantly from basic materials; industrials; technology; and consumer goods (all higher means). Financials and basic resources has the highest difference of –20.8613, p-value 0.0001 *, followed by financials and consumer goods −16.4194, p-value of 0.0001 * whilst health care and basic resources show a difference of −11.9048 with a p-value of 0.0101 *. The p-values are too small (≤0.05) which means that the null hypothesis is not supported. Therefore, the null hypothesis that there is no significant difference in this SP measure when compared to overall industry score is rejected.

5.2.2. Human Rights and Supply Chain (IC3)

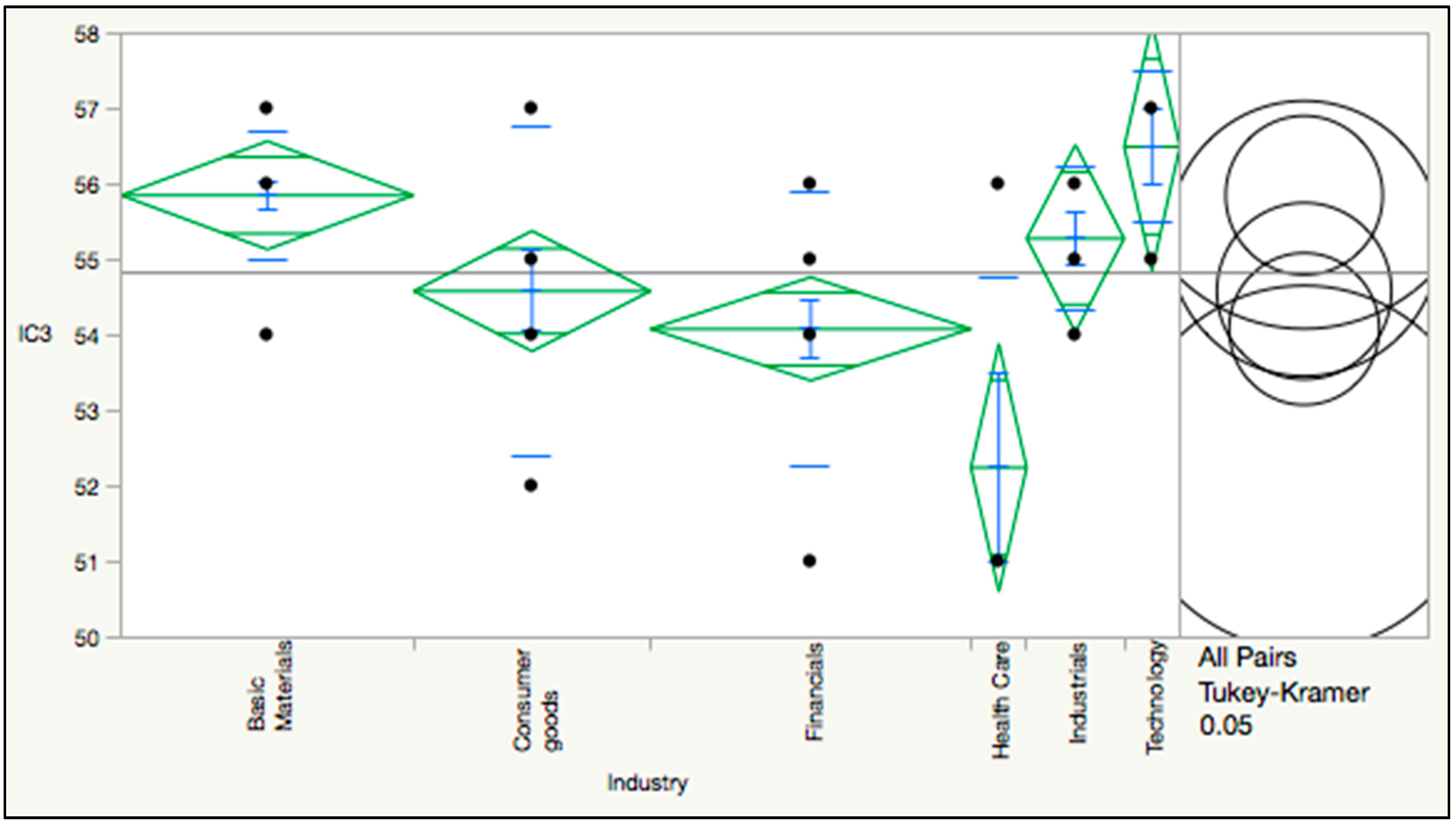

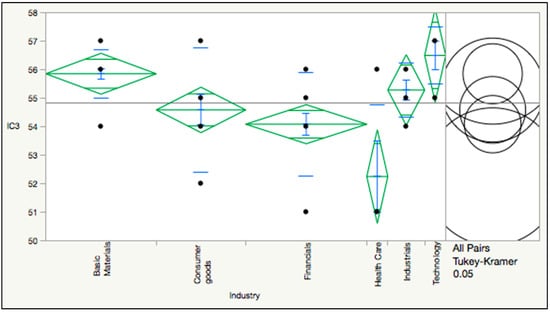

In Table 7 and Figure 2 it was investigated whether IC3 shows individual differences between individual ESG scores and the overall industry score.

Figure 2.

One-way ANOVA of IC3 by industry.

The parametric test in Table 7 and Figure 2 revealed that the human rights and supply chain variable has the highest mean difference between technology and health care (4.250), with a p-value of 0.0064 *, followed by basic materials and health care (3.607143) with a p-value of 0.0020 whereas Industrials and Health has a difference of 3.035714, with a p-value of 0.0485 *. Basic materials and financials show the least difference (1.770) and p-value of 0.0084 *. P-values that are less than 0.05 means that the null hypothesis is not supported. Therefore, the null hypothesis that there is no significant difference in SP measures when compared to overall industry score is rejected.

5.2.3. Compensation and Benefits (IE1)

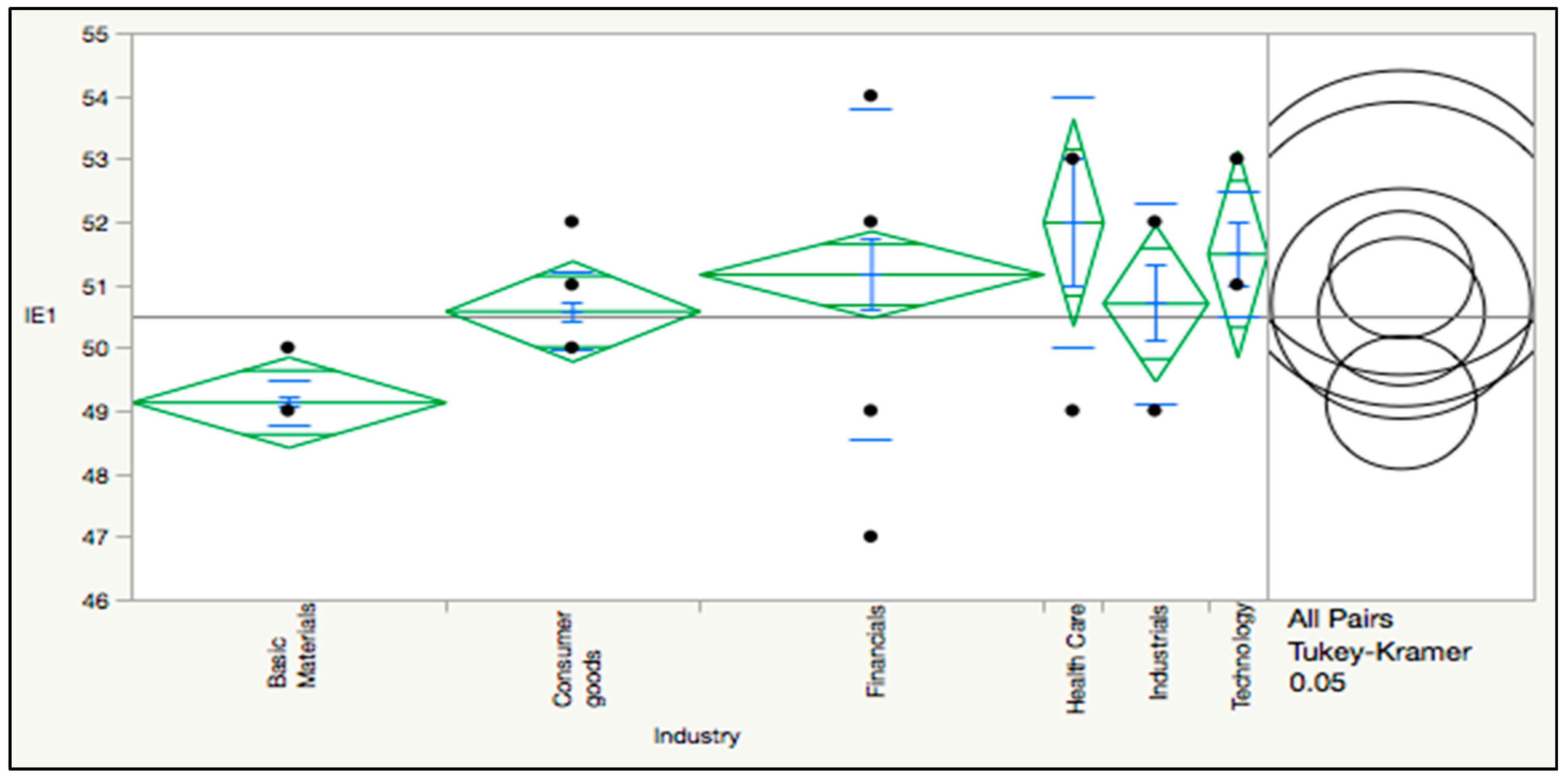

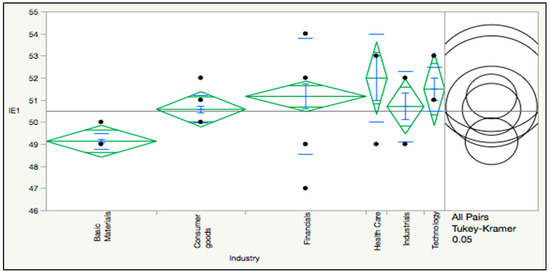

In Table 8 and Figure 3, it was investigated whether IE1 show differences between individual ESG scores and the overall industry score. The compensation and benefits (IE1) measurement is portrayed in Table 8 and Figure 3.

Figure 3.

One-way ANOVA of IE1 by industry.

The multiple comparison Tukey HSD test on the compensation and benefits dimension revealed a significant difference between health care and basic materials (2.857), with a p-value of 0.0260 * and between financials and basic materials (2.031) with a p-value of 0.0016 *. There is evidence that the calculated p-values are less than 0.05 indicating strong evidence against the null hypothesis, therefore the null hypothesis should be rejected.

However, the HSD test revealed that there is a difference in the means of SP measures of individual scores when compared to the overall industry score. Therefore, the alternate hypothesis is accepted and conclude that there are significant differences on the three (3) performance indicators: IC1 (<0.0001 *), IC3 (0.0002 *) and IE1 (0.0011 *). The existence of a sector effect in SP results is supported by [91,92]. According to [91], companies affiliated in sustainability-sensitive industries such as healthcare, basic materials, and energy sectors are more likely to disclose environmental information whereas companies operating in the financial sector revealed a statistically significant negative effect.

6. Conclusions

This article examined the SP of companies listed on the FTSE/JSE RI Index using ESG indicators. The index is representative of six industry sectors, namely basic materials, consumer goods, financials, health care, industrials and technology. The CSRhub rating as an indicator of perceived SP indicated that companies affiliated with Industrials scored the highest mean of 56.6, whilst companies under technology scored the lowest mean of 54.7. This might be an indication of the environmental issues encountered by Industrials. The result indicating that financials and health care could be linked with low reporting, whilst basic materials and industrials are associated with high reporting confirmed the result of [85] who found that industry membership influences the adoption of integrated reporting. Furthermore, no evidence was found that ESG ratings vary between industries in the population examined and therefore it is in agreement with the results of [100]: the results of our analysis did not reveal any significant differences between sectors.

The article answers the hypothesised question by assessing the ESG indicators of the FTSE/JSE RI Index to determine if companies in different industries respond differently to divergent stakeholders’ interests, needs and pressures which may in turn influence their priorities when prioritising which ESG activities to undertake. From the above discussion, the results accept the null hypothesis. The study found that industry plays a significant role in determining the SP of a company represented on the FTSE/JSE RI Index. This is coherent with prior studies [52,78,79,85,86]. It is therefore concluded that ESG ratings of companies are not determined by the industry to which they belong.

7. Future Research

Future studies can look at a longitudinal analysis to shed light on the pattern of sustainability practices of FTSE/JSE RI by industry.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, R.M.M., H.M.v.d.P. and B.M.; methodology, R.M.M. and B.M.; validation, R.M.M., H.M.v.d.P. and B.M.; formal analysis, R.M.M.; investigation, R.M.M.; resources, R.M.M.; data curation, R.M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M.M.; writing—review and editing, H.M.v.d.P. and B.M.; visualization, R.M.M., H.M.v.d.P. and B.M.; supervision, H.M.v.d.P. and B.M.; project administration, R.M.M., and H.M.v.d.P.; funding acquisition, R.M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a University of South Africa bursary for the lead author—73060550 as well as the National Research Foundation (NRF)—Grant number 119862.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data was purchased for research purposes from the CSRHub LLC in a transaction dated 8 March 2019. Data are available from the Author at the permission of the CSRhub.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to CSRHub company.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

CSRHub Ratings by Company.

Table A1.

CSRHub Ratings by Company.

| Industry | Company | Community Development and Philanthropy | Human rights and Supply Chain | Product | Compensation and Benefits | Diversity and Labour Right | Training and Health and Safety | Energy and Climate Change | Environment Policy and Reporting | Resource Management | Board of Directors | Leadership Ethics | Transparency and Reporting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Materials | AECI | 63 | 44 | 57 | 61 | 61 | 60 | 60 | 61 | 58 | 63 | 63 | 53 |

| Basic Materials | Anglo American | 49 | 47 | 54 | 57 | 59 | 51 | 52 | 63 | 53 | 55 | 45 | 50 |

| Basic Materials | Anglo American Platinum | 49 | 44 | 52 | 49 | 53 | 47 | 54 | 64 | 53 | 48 | 43 | 53 |

| Basic Materials | Anglogold Ashanti | 43 | 37 | 45 | 45 | 52 | 36 | 49 | 61 | 46 | 55 | 46 | 54 |

| Basic Materials | African Rainbow Minerals Ltd. | 66 | 43 | 58 | 68 | 66 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 51 | 51 | 54 |

| Basic Materials | Assore Ltd. | 58 | 27 | 55 | 59 | 46 | 55 | 43 | 56 | 57 | 40 | 46 | 40 |

| Basic Materials | BHP Billiton | 46 | 53 | 56 | 65 | 62 | 58 | 53 | 62 | 47 | 61 | 45 | 50 |

| Basic Materials | Exxaro Resources | 50 | 43 | 54 | 55 | 57 | 52 | 61 | 65 | 56 | 47 | 50 | 51 |

| Basic Materials | Gold Fields | 49 | 42 | 51 | 44 | 53 | 40 | 53 | 65 | 54 | 52 | 48 | 53 |

| Basic Materials | Glencore | 43 | 46 | 43 | 51 | 55 | 49 | 51 | 58 | 45 | 56 | 44 | 49 |

| Basic Materials | Harmony | 61 | 36 | 64 | 70 | 57 | 58 | 60 | 70 | 58 | 65 | 67 | 68 |

| Basic Materials | Impala Platinum Hlds | 59 | 35 | 69 | 66 | 70 | 65 | 58 | 66 | 60 | 66 | 57 | 61 |

| Basic Materials | Kumba Iron Ore | 42 | 48 | 55 | 58 | 62 | 54 | 60 | 68 | 51 | 50 | 48 | 55 |

| Basic Materials | Mondi Ltd. | 56 | 53 | 67 | 53 | 59 | 52 | 59 | 73 | 61 | 55 | 44 | 51 |

| Basic Materials | Mondi Plc | 61 | 56 | 72 | 58 | 64 | 65 | 68 | 77 | 63 | 63 | 51 | 59 |

| Basic Materials | Northam Platinum | 70 | 38 | 69 | 71 | 68 | 57 | 54 | 61 | 59 | 59 | 63 | 61 |

| Basic Materials | Omnia Holdings Ltd. | 67 | 49 | 52 | 55 | 63 | 67 | 61 | 64 | 59 | 50 | 59 | 52 |

| Basic Materials | South32 | 47 | 49 | 62 | 54 | 58 | 59 | 44 | 54 | 44 | 63 | 47 | 45 |

| Basic Materials | Sappi | 56 | 53 | 68 | 64 | 62 | 60 | 55 | 73 | 55 | 49 | 48 | 56 |

| Basic Materials | Sibanye Gold | 52 | 29 | 55 | 43 | 54 | 55 | 50 | 54 | 52 | 65 | 51 | 55 |

| Basic Materials | Sasol | 53 | 38 | 63 | 51 | 55 | 50 | 47 | 65 | 52 | 55 | 46 | 55 |

| Consumer goods | AVI | 67 | 46 | 59 | 65 | 63 | 64 | 42 | 59 | 54 | 61 | 61 | 53 |

| Consumer goods | British American Tobacco PLC | 51 | 39 | 48 | 58 | 58 | 57 | 65 | 66 | 53 | 64 | 43 | 50 |

| Consumer goods | Compagnie Financiere Richemont AG | ||||||||||||

| Consumer goods | Clicks Group Ltd. | 55 | 43 | 49 | 60 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 53 | 52 | 57 | 49 | 47 |

| Consumer goods | Curro Holdings | 46 | 43 | 49 | 47 | 49 | 48 | 50 | 49 | 54 | 49 | 50 | 38 |

| Consumer goods | Mr Price Group | 56 | 45 | 60 | 56 | 62 | 58 | 60 | 53 | 51 | 42 | 39 | 40 |

| Consumer goods | Massmart Holdings | 42 | 47 | 60 | 65 | 75 | 61 | 56 | 64 | 53 | 55 | 55 | 58 |

| Consumer goods | Naspers | 53 | 51 | 59 | 51 | 52 | 52 | 63 | 61 | 57 | 45 | 39 | 36 |

| Consumer goods | Oceana Group | 74 | 51 | 69 | 51 | 68 | 69 | 61 | 65 | 63 | 65 | 66 | 61 |

| Consumer goods | Pioneer Food Group | 54 | 57 | 64 | 65 | 66 | 58 | 59 | 58 | 53 | 51 | 45 | 48 |

| Consumer goods | Pick N Pay Stores | 51 | 49 | 63 | 61 | 66 | 59 | 62 | 63 | 59 | 52 | 52 | 54 |

| Consumer goods | Steinhoff International Holdings N.V. | 41 | 44 | 58 | 63 | 62 | 52 | 54 | 59 | 46 | 51 | 44 | 47 |

| Consumer goods | The Spar Group | 53 | 45 | 59 | 58 | 62 | 58 | 65 | 62 | 59 | 52 | 50 | 51 |

| Consumer goods | Tiger Brands | 54 | 46 | 61 | 63 | 62 | 55 | 59 | 59 | 59 | 48 | 47 | 48 |

| Consumer goods | The Foschini Group Ltd. | 50 | 39 | 59 | 49 | 61 | 57 | 60 | 57 | 50 | 51 | 42 | 48 |

| Consumer goods | Tongaat Hulett | 59 | 43 | 56 | 54 | 63 | 72 | 54 | 58 | 53 | 63 | 64 | 56 |

| Consumer goods | Truworths International | 47 | 46 | 55 | 56 | 58 | 54 | 60 | 52 | 53 | 49 | 47 | 46 |

| Consumer goods | Woolworths Holdings | 61 | 62 | 66 | 64 | 65 | 61 | 68 | 71 | 68 | 52 | 52 | 57 |

| Financials | Attacq Limited | 53 | 47 | 55 | 49 | 53 | 53 | 58 | 58 | 62 | 52 | 52 | 44 |

| Financials | Barclays Africa Group Ltd. | 55 | 50 | 58 | 51 | 60 | 56 | 61 | 69 | 57 | 39 | 39 | 52 |

| Financials | Capital & Counties Properties PLC | 54 | 51 | 55 | 55 | 51 | 62 | 69 | 58 | 64 | 64 | 53 | 37 |

| Financials | Coronation Fund Managers | 50 | 50 | 60 | 48 | 58 | 53 | 63 | 52 | 51 | 53 | 46 | 36 |

| Financials | Capitec Bank Hldgs Ltd. | 46 | 43 | 51 | 62 | 63 | 61 | 54 | 48 | 46 | 36 | 36 | 33 |

| Financials | Discovery Ltd. | 46 | 48 | 65 | 68 | 68 | 57 | 64 | 58 | 51 | 39 | 45 | 49 |

| Financials | Firstrand Limited | 58 | 54 | 64 | 63 | 63 | 59 | 64 | 67 | 63 | 43 | 48 | 52 |

| Financials | Growthpoint Prop Ltd. | 50 | 51 | 51 | 69 | 67 | 59 | 75 | 70 | 68 | 49 | 49 | 52 |

| Financials | Hammerson Plc | 62 | 60 | 66 | 72 | 66 | 69 | 72 | 78 | 74 | 64 | 53 | 51 |

| Financials | Hyprop Investments Ltd. | 44 | 47 | 43 | 62 | 62 | 67 | 66 | 54 | 58 | 49 | 47 | 44 |

| Financials | Investec Ltd. | 61 | 48 | 63 | 52 | 64 | 57 | 62 | 64 | 56 | 34 | 35 | 44 |

| Financials | Investec PLC | 60 | 50 | 65 | 59 | 63 | 57 | 62 | 65 | 55 | 52 | 40 | 47 |

| Financials | Intu Properties Plc/ Capital shopping centres Plc | 54 | 63 | 71 | 68 | 63 | 70 | 71 | 75 | 70 | 68 | 57 | 55 |

| Financials | JSE | 72 | 38 | 66 | 60 | 57 | 60 | 55 | 51 | 70 | 60 | 64 | 48 |

| Financials | Liberty Hldgs. | 49 | 46 | 56 | 59 | 63 | 47 | 56 | 55 | 49 | 42 | 40 | 48 |

| Financials | MMI Holdings | 46 | 43 | 54 | 53 | 59 | 45 | 62 | 55 | 49 | 46 | 43 | 47 |

| Financials | Nedbank Group | 58 | 53 | 64 | 61 | 69 | 63 | 68 | 69 | 63 | 39 | 43 | 52 |

| Financials | Old Mutual Ltd. | 49 | 45 | 55 | 52 | 53 | 52 | 53 | 52 | 54 | 50 | 50 | 43 |

| Financials | Quilter | ||||||||||||

| Financials | Redefine Properties | 48 | 50 | 47 | 67 | 67 | 65 | 68 | 58 | 61 | 43 | 46 | 44 |

| Financials | Standard Bank Group | 57 | 56 | 63 | 58 | 65 | 57 | 68 | 70 | 58 | 37 | 39 | 53 |

| Financials | Sanlam | 56 | 47 | 60 | 61 | 69 | 57 | 65 | 67 | 60 | 48 | 48 | 55 |

| Financials | Santam | 76 | 53 | 58 | 64 | 67 | 63 | 61 | 60 | 69 | 59 | 62 | 58 |

| Health Care | Aspen Pharmacare Holdings | 51 | 45 | 65 | 61 | 59 | 59 | 62 | 66 | 60 | 43 | 45 | 48 |

| Health Care | Life Healthcare Group Holdings | 49 | 51 | 57 | 62 | 63 | 61 | 64 | 57 | 56 | 54 | 48 | 45 |

| Health Care | Mediclinic International plc | 52 | 53 | 56 | 49 | 50 | 56 | 62 | 69 | 63 | 58 | 44 | 44 |

| Health Care | Netcare | 56 | 50 | 63 | 54 | 61 | 61 | 66 | 62 | 57 | 46 | 46 | 50 |

| Industrials | Barloworld | 63 | 49 | 63 | 69 | 66 | 55 | 60 | 64 | 65 | 57 | 62 | 66 |

| Industrials | Grindrod | 67 | 39 | 57 | 51 | 55 | 67 | 57 | 64 | 62 | 61 | 64 | 51 |

| Industrials | Imperial Holdings | 48 | 49 | 51 | 54 | 55 | 46 | 58 | 59 | 54 | 50 | 42 | 47 |

| Industrials | KAP Industrial Holdings Ltd. | 63 | 42 | 58 | 58 | 55 | 61 | 49 | 63 | 57 | 67 | 51 | 44 |

| Industrials | Nampak | 60 | 49 | 58 | 60 | 66 | 61 | 64 | 64 | 59 | 63 | 58 | 60 |

| Industrials | Remgro | 44 | 44 | 54 | 55 | 56 | 54 | 65 | 58 | 50 | 41 | 40 | 41 |

| Industrials | Reunert | 65 | 41 | 69 | 59 | 61 | 55 | 62 | 68 | 67 | 65 | 61 | 57 |

| Technology | EOH Holdings Ltd. | 67 | 40 | 48 | 50 | 55 | 61 | 51 | 55 | 66 | 56 | 52 | 46 |

| Technology | MTN Group | 59 | 46 | 55 | 55 | 59 | 57 | 59 | 62 | 55 | 47 | 43 | 50 |

| Technology | Telkom SA SOC | 51 | 47 | 46 | 61 | 58 | 61 | 60 | 58 | 51 | 55 | 48 | 48 |

| Technology | Vodacom Group | 58 | 49 | 63 | 63 | 67 | 62 | 65 | 65 | 59 | 49 | 47 | 54 |

References

- WCED: World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future (Brundtland Report); Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987. Available online: https://global.oup.com/academic/product/our-common-future-9780192820808?cc=cn&lang=en& (accessed on 1 October 2021).

- Onuora-Oguno, A.C.; Egbewole, W.O.; Kleven, T.E. Education Law, Strategic Policy and Sustainable Development in Africa; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Qu, Y.; Javed, S.A.; Zafar, A.U.; Rehman, S.U. Relation of environment sustainability to CSR and green innovation: A case of Pakistani manufacturing industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 253, 119938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.Z.X. Environmental, social and governance (ESG) activity and firm performance: A review and consolidation. Account. Finance 2019, 61, 335–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.A.; Forster, W.R. CSR and Stakeholder Theory: A Tale of Adam Smith. J. Bus. Ethic- 2012, 112, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S. Institutionalization of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) in India and Its Effects on CSR Reporting: A Case Study of the Petroleum and Gas Industry. Mandated Corp. Soc. Responsib. Evid. India 2019, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, F.; Leopizzi, R.; Pizzi, S.; Milone, V. The Non-Financial Reporting Harmonization in Europe: Evolutionary Pathways Related to the Transposition of the Directive 95/2014/EU within the Italian Context. Sustainability 2019, 12, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socoliuc, M.; Cosmulese, C.-G.; Ciubotariu, M.-S.; Mihaila, S.; Arion, I.-D.; Grosu, V. Sustainability Reporting as a Mixture of CSR and Sustainable Development. A Model for Micro-Enterprises within the Romanian Forestry Sector. Sustainability 2020, 12, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Lee, S. The impact of material and immaterial sustainability on firm performance: The moderating role of franchising strategy. Tour. Manag. 2019, 77, 103999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekhili, M.; Nagati, H.; Chtioui, T.; Rebolledo, C. Corporate social responsibility disclosure and market value: Family versus nonfamily firms. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 77, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, G.; Cupertino, S.; Rinaldi, L.; Riccaboni, A. Integrated Management Approach Towards Sustainability: An Egyptian Business Case Study. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruf, B.M.; Muralidhar, K.; Brown, R.M.; Janney, J.J.; Paul, K. An Empirical Investigation of the Relationship Between Change in Corporate Social Performance and Financial Performance: A Stakeholder Theory Perspective. J. Bus. Ethic 2001, 32, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele-Schober, T. The Importance of Esg for Mineral Reporting. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2021, 121, VIII–XI. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.R.; Jang, J.Y. The Impact of ESG Management on Investment Decision: Institutional Investors’ Perceptions of Country-Specific ESG Criteria. Int. J. Financial Stud. 2021, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strielkowski, W.; Tarkhanova, E.; Baburina, N.; Streimikis, J. Corporate Social Responsibility and the Renewable Energy Development in the Baltic States. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, V.H.; Fisch, J.; Fairfax, L.; Vandenbergh, M.; Miazad, A.; Lin, T.; Allen, H.; Laby, A.; Condon, M.; Park, S. Modernizing ESG Disclosure. University of Illinois Law Review. 2021. Forthcoming. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3845145. (accessed on 9 October 2021).

- Hughes, A.; Urban, M.; Wójcik, D. Alternative ESG Ratings: How Technological Innovation Is Reshaping Sustainable Investment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanaev, S.; Ghimire, B. When ESG meets AAA: The effect of ESG rating changes on stock returns. Finance Res. Lett. 2021, 102302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamura, T. Risk Mitigation and Return Resilience for High Yield Bond ETFs with ESG Components. Finance Res. Lett. 2020, 41, 101866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.; Managi, S. Disclosure or action: Evaluating ESG behavior towards financial performance. Finance Res. Lett. 2021, 102108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.; Keeley, A.R.; Managi, S. Does sustainability activities performance matter during financial crises? Investigating the case of COVID-19. Energy Policy 2021, 155, 112330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reber, B.; Gold, A.; Gold, S. ESG Disclosure and Idiosyncratic Risk in Initial Public Offerings. J. Bus. Ethic 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setia, N.; Abhayawansa, S.; Joshi, M.; Huynh, A.V. Integrated reporting in South Africa: Some initial evidence. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2015, 6, 397–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerreiro, J.; Pacheco, M. How Green Trust, Consumer Brand Engagement and Green Word-of-Mouth Mediate Purchasing Intentions. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, M.D.T.; Harkink, K.M.; Barth, S. Making Green Stuff? Effects of Corporate Greenwashing on Consumers. J. Bus. Tech. Commun. 2017, 32, 77–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demuijnck, G.; Fasterling, B. The Social License to Operate. J. Bus. Ethic 2016, 136, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herremans, I.M.; Nazari, J.A.; Mahmoudian, F. Stakeholder Relationships, Engagement, and Sustainability Reporting. J. Bus. Ethic 2015, 138, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Perrini, F. Investigating Stakeholder Theory and Social Capital: CSR in Large Firms and SMEs. J. Bus. Ethic 2009, 91, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.I.; Choi, J. Stakeholder Influence on Local Corporate Social Responsibility Activities of Korean Multinational Enterprise Subsidiaries. Emerg. Mark. Finance Trade 2015, 51, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A.; Costa, R.; Ghiron, N.L.; Menichini, T. Materiality analysis in sustainability reporting: A tool for directing corporate sustainability towards emerging economic, environmental and social opportunities. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2019, 25, 1016–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrechts, W.; Son-Turan, S.; Reis, L.; Semeijn, J. Lean, Green and Clean? Sustainability Reporting in the Logistics Sector. Logistics 2019, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasan, M.; Mio, C. Fostering Stakeholder Engagement: The Role of Materiality Disclosure in Integrated Reporting. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2016, 26, 288–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morioka, S.N.; De Carvalho, M.M. A systematic literature review towards a conceptual framework for integrating sustainability performance into business. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 136, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcoux, A.M. A fiduciary argument against stakeholder theory Alexei M. Marcoux 2003, 13, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Fernandez, M. Social responsibility and financial performance: The role of good corporate governance. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2016, 19, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhling, K.; Murguía, D.I.; Godfrid, J. Sustainability Reporting in the Mining Sector: Exploring Its Symbolic Nature. Bus. Soc. 2017, 58, 191–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantan, B.S.; Thomas, K. Measuring what matters: A sector-specific corporate social responsibility framework for quality practice. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2021, 63, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oncioiu, I.; Popescu, D.-M.; Aviana, A.; Șerban, A.; Rotaru, F.; Petrescu, M.; Marin-Pantelescu, A. The Role of Environmental, Social, and Governance Disclosure in Financial Transparency. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champagne, C.; Coggins, F.; Sodjahin, A. Can extra-financial ratings serve as an indicator of ESG risk? Glob. Finance J. 2021, 100638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadstock, D.C.; Chan, K.; Cheng, L.T.; Wang, X. The role of ESG performance during times of financial crisis: Evidence from COVID-19 in China. Finance Res. Lett. 2020, 38, 101716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueti, R.; Ciciretti, R.; Dalò, A.; Nicolosi, M. ESG investing: A chance to reduce systemic risk. J. Financ. Stab. 2021, 54, 100887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climent, R.B.; Garrigues, I.F.-F.; Paraskevopoulos, I.; Santos, A. ESG Disclosure and Portfolio Performance. Risks 2021, 9, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, H.; Unger, S.; Entezarian, M.R. Information Content Measurement of ESG Factors via Entropy and Its Impact on Society and Security. Information 2021, 12, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lock, I.; Seele, P. Analyzing Sector-Specific CSR Reporting: Social and Environmental Disclosure to Investors in the Chemicals and Banking and Insurance Industry. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 22, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, A.S.; Orazalin, N.; Uyar, A.; Shahbaz, M. CSR achievement, reporting, and assurance in the energy sector: Does economic development matter? Energy Policy 2020, 149, 112007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.M. Instrumental Stakeholder Theory: A Synthesis of Ethics and Economics. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantrell, J.E.; Kyriazis, E.; Noble, G. Developing CSR Giving as a Dynamic Capability for Salient Stakeholder Management. J. Bus. Ethic 2014, 130, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörisch, J.; Freeman, R.E.; Schaltegger, S. Applying Stakeholder Theory in Sustainability Management. Organ. Environ. 2014, 27, 328–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Klerk, M.; de Villiers, C.; Van Staden, C. The influence of corporate social responsibility disclosure on share prices. Pac. Account. Rev. 2015, 27, 208–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, N.G.; Berman, S.; Van Buren, H. Stakeholder Theory and Value Creation Models in Brazilian Firms. Rev. Bus. Manag. 2015, 17, 911–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sama-lang, I.F.; Njonguo, A.Z. The Stakeholder Theory of Corporate Control and the Place of Ethics in OHADA: The Case of Cameroon. Afr. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 10, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bridoux, F.; Stoelhorst, J.W. Stakeholder Relationships and Social Welfare: A Behavioral Theory of Contributions to Joint Value Creation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2016, 41, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumay, J.; Bernardi, C.; Guthrie, J.; DeMartini, P. Integrated reporting: A structured literature review. Account. Forum 2016, 40, 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranängen, H. Stakeholder management theory meets CSR practice in Swedish mining. Miner. Econ. 2016, 30, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.; Earp, J.B.; Showalter, D.S.; Williams, P.F. Corporate Sustainability Reporting and Stakeholder Concerns: Is There a Disconnect? Account. Horizons 2016, 31, 83–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, S. Stakeholder Theory Classification: A Theoretical and Empirical Evaluation of Definitions. J. Bus. Ethic 2015, 142, 437–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvare, R.; Johansson, P. Management for sustainability—A stakeholder theory. Total. Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2010, 21, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.M.; Wicks, A.C. Convergent Stakeholder Theory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O.; Heras-Saizarbitoria, I. Managing Biodiversity Through Stakeholder Involvement: Why, Who, and for What Initiatives? J. Bus. Ethic- 2015, 140, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeyen, A.; Beckmann, M.; Wolters, S. Actor and Institutional Dynamics in the Development of Multi-stakeholder Initiatives. J. Bus. Ethic- 2014, 135, 341–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodhi, M.S. Conceptualizing Social Responsibility in Operations Via Stakeholder Resource-Based View. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dögl, C.; Behnam, M. Environmentally Sustainable Development through Stakeholder Engagement in Developed and Emerging Countries. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2014, 24, 583–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, A.M.; Rutherford, M.A.; Sharfman, M.P. Stakeholder-Centric Governance and Corporate Social Performance: A Cross-National Study. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2015, 23, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, D.; Magnan, M. The Economic Relevance of Environmental Disclosure and its Impact on Corporate Legitimacy: An Empirical Investigation. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2013, 24, 431–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diouf, D.; Boiral, O. The quality of sustainability reports and impression management. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2017, 30, 643–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haro, S.P.-D.; Bitektine, A. Global sustainability pressures and strategic choice: The role of firms’ structures and non-market capabilities in selection and implementation of sustainability initiatives. J. World Bus. 2015, 50, 326–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, R.Y. A review of corporate sustainability reporting tools (SRTs). J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 164, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, J.A.; Hrazdil, K.; Mahmoudian, F. Assessing social and environmental performance through narrative complexity in CSR reports. J. Contemp. Account. Econ. 2017, 13, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matisoff, D. Sources of specification errors in the assessment of voluntary environmental programs: Understanding program impacts. Policy Sci. 2014, 48, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Pinkse, J.; Preuss, L.; Figge, F. Ambidexterity for Corporate Social Performance. Organ. Stud. 2015, 37, 213–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Boiral, O.; Iraldo, F. Internalization of Environmental Practices and Institutional Complexity: Can Stakeholders Pressures Encourage Greenwashing? J. Bus. Ethic- 2015, 147, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netto, S.V.D.F.; Sobral, M.F.F.; Ribeiro, A.R.B.; Soares, G.R.D.L. Concepts and forms of greenwashing: A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienes, D.; Sassen, R.; Fischer, J. What are the drivers of sustainability reporting? A systematic review. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2016, 7, 154–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crilly, D.; Hansen, M.; Zollo, M. The Grammar of Decoupling: A Cognitive-Linguistic Perspective on Firms’ Sustainability Claims and Stakeholders’ Interpretation. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 705–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuji, O.K. Corporate social responsibility, juridification and globalisation: ‘inventive interventionism’ for a ‘paradox’. Int. J. Law Context 2015, 11, 265–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. Promoting more socially responsible corporations through a corporate law regulatory framework. Leg. Stud. 2017, 37, 103–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackers, B.; Eccles, N. Mandatory corporate social responsibility assurance practices. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2015, 28, 515–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkl-Davies, D.M.; Brennan, N.M.; McLeay, S.J. Impression management and retrospective sense-making in corporate narratives. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2011, 24, 315–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. Corporate social responsibility and access to finance. Strat. Manag. J. 2013, 35, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, C.; Rinaldi, L.; Unerman, J. Integrated Reporting: Insights, gaps and an agenda for future research. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2014, 27, 1042–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JSE FTSE Russell. FTSE. JSE Responsible Investment Index Series. Gr. Rules 2015, April, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Directors Southern Africa. King IV-Report on Corporate Governance for South Africa; Institute of Directors Southern Africa: Cape Town, South Africa, 2016. Available online: https://www.iodsa.co.za/page/DownloadKingIVapp (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Ali, W.; Frynas, J.G.; Mahmood, Z. Determinants of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Disclosure in Developed and Developing Countries: A Literature Review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T.-K.; Wang, Y.-H. Determinants of Social Disclosure Quality in Taiwan: An Application of Stakeholder Theory. J. Bus. Ethic 2014, 129, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trébucq, S.; Magnaghi, E. Using the EFQM excellence model for integrated reporting: A qualitative exploration and evaluation. Res. Int. Bus. Finance 2017, 42, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Amico, E.; Coluccia, D.; Fontana, S.; Solimene, S. Factors Influencing Corporate Environmental Disclosure. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2014, 25, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thijssens, T.; Bollen, L.; Hassink, H. Secondary Stakeholder Influence on CSR Disclosure: An Application of Stakeholder Salience Theory. J. Bus. Ethic 2015, 132, 873–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zeng, S.; Ma, H.; Chen, H. Does commitment to environmental self-regulation matter? An empirical examination from China. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 932–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceituno, J.V.F.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L.; Garcia-Sanchez, I.-M. Is integrated reporting determined by a country's legal system? An exploratory study. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 44, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, M.; Azzone, G.; Mapelli, F. Corporate Social Responsibility strategies in the utilities sector:A comparative study. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 18, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Álvarez, I.; Ortas, E. Corporate environmental sustainability reporting in the context of national cultures: A quantile regression approach. Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 26, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Zein, S.A.; Consolacion-Segura, C.; Huertas-Garcia, R. The Role of Sustainability in Brand Equity Value in the Financial Sector. Sustainability 2019, 12, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, J.B.; Branco, M.C. Controversial sectors in banks’ sustainability reporting. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2019, 26, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O.; Heras-Saizarbitoria, I. Sustainability reporting assurance: Creating stakeholder accountability through hyperreality? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 243, 118596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mio, C.; Fasan, M.; Costantini, A. Materiality in integrated and sustainability reporting: A paradigm shift? Bus. Strat. Environ. 2019, 29, 306–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keig, D.L. Formal and Informal Institutional Influences on Multinational Enterprise Social Responsibility: Two Empirical Studies. Ph.D. Thesis, Kennesaw State University, Kennesaw, GA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- CSR Hub. CSRHub Category and Subcategory Schema Community; CSR Hub: Munich, Germany, 2014; Available online: https://www.csrhub.com/ (accessed on 30 August 2021).

- Soh, D.; Martinov-Bennie, N. Internal auditors’ perceptions of their role in environmental, social and governance assurance and consulting. Manag. Audit. J. 2015, 30, 80–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. Corporate sustainability and responsibility: Creating value for business, society and the environment. Asian J. Sustain. Soc. Responsib. 2017, 2, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Orzes, G.; Jia, F.; Chen, L. Does GRI Sustainability Reporting Pay Off? An Empirical Investigation of Publicly Listed Firms in China. Bus. Soc. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vormedal, I.; Ruud, A. Sustainability reporting in Norway—An assessment of performance in the context of legal demands and socio-political drivers. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2006, 18, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kansal, M.; Joshi, M.; Batra, G.S. Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosures: Evidence from India. Adv. Account. 2014, 30, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).