Abstract

Video game streaming (VGS) has attracted millions of users and shown unprecedented growth globally. With technological development, these appealing media have largely influenced the sustainable development of society and the economy. VGS creates a pleasant atmosphere and provides various novel features to please the viewers, induce positive emotions, and facilitate users’ engagement. Integrating several personal characteristics as moderators, this study applied cognitive emotion theory to explore the antecedent of viewers’ engagement in VGS. Using 308 empirical data, the research results reveal that broadcaster attractiveness and the para-social relationship are positively associated with the viewers’ positive emotion, which eventually leads to engagement. In addition, personal characteristics play significant roles as moderators between VGS features and the viewers’ positive emotions. The results provide theoretical implications for VGS research and useful insights for VGS platform managers and policymakers to enable a sustainable profit model and the growth of VGS.

1. Introduction

Video game streaming (VGS) is a real-time video social media platform that combines traditional broadcasting and internet gaming [1]. The number of its users has continuously increased over the past years. As of December 2020, the number of live-streaming users in China had reached 617 million, an increase of 57.03 million from March 2020, accounting for 62.4 percent of all Internet users, with VGS users particularly accounting for 19.3 percent of all Internet users [2]. Since technological innovation often efficiently balances economic progress, resource consumption, and environmental challenges, the development of VGS is directly linked to sustainability [3]. VGS makes it easier for viewers to form positive relationships with broadcasters and other viewers, promoting harmony and cooperation [4,5]. Furthermore, VGS implemented a sustainable business model to engage and enable viewers without depleting natural resources, which benefits all parties involved, including the broadcaster, the viewer, the platform, society, and economic progress.

VGS uses technological innovation and a long-term economic approach to develop a unique and enjoyable social platform. The VGS platform entails the three most critical features that are the platform content feature, the functional feature, and the social feature, all of which in one way or another provide a pleasant environment that delights viewers and elicits positive emotions, ultimately increasing user engagement. When broadcasters comprehensively understand and match viewer preferences, in terms of streaming content, game-playing skills, and personality, positive emotions result due to gratification. As a social feature, the para-social relationship arising from the interaction between the broadcasters and viewers facilitated by the bullet-screen provides a sense of belonging for viewers, which then sparks positive emotions. When positive emotions, such as satisfaction are elicited, viewers become more reactive and interested, leading to real engagement behavior such as commenting or hitting the like/heart button on content provided by broadcasters through the bullet-screen feature [6]. Platforms like Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, and Twitch have integrated VGS into their services [7], thus contributing to the unprecedented growth of the phenomenon. This remarkable expansion of VGS has enormous opportunities for researchers to examine viewers’ emotions and behaviors as well as the underlying mechanism of the phenomenon [8].

Research on the VGS phenomenon and user behaviors is still at its early stages. Most prior studies have explored determinants of viewers’ watching intention [9,10,11,12] and broadcasting intention [13] in live-streaming platforms. While using the uses and gratifications theory and the media richness theory, Hsu et al. (2020) [12] determined the antecedents of continuous watching intention, which they attributed to gratifications such as entertainment and sociability and the individual’s perception of media richness. Still with the same framework, Cabeza-Ramírez et al., (2020) [9] investigated the mediating effects of socio-demographic variables between motivation (entertainment, social, and informational) and usage of VGS platforms. On the contrary, Pappas et al. (2020) [11] used a conceptual model to investigate how motives and emotions interact with one another to explain consumer satisfaction in social networking sites. In consideration of the VGS context, Xu et al. (2021) [14] employed the stimuli-organism-response (S-O-R) framework to identify significant elements influencing audience engagement. Worth noting is the fact that these pioneering studies, while attempting to unearth the antecedents of viewer engagement, they mainly centered their focus on the viewers’ behaviors [15]. However, the viewer’s engagement is not confined to behavioral intention; the emotional motive has a substantial impact as well [16], more so in the VGS environment where people engage in the platform solely for hedonic reasons. In affirmation, Xu et al. (2020) [17] argued that the users’ decision-making process leading to engagement is prompted by their emotional state. As such, it is of great significance to note that a scarcity of research has been conducted to uncover the rationale of VGS viewers’ emotions, which ultimately result in engagement. This was an objective this study intended to address.

Scholars believe that customer engagement is defined from three perspectives, namely, behavioral, psychological and cognitive, and emotional perspectives [18]. A model fit to thoroughly investigate that would be cognitive emotion theory (CET), as it investigates how the cognition of an individual impacts their emotional states and successive behavior [19]. The framework highlights how our perception of our surroundings has a major effect on our emotions and decision-making. Addressing the paucity of a CET framework that explains viewers’ engagement in the VGS context, we identified three VGS features as the CET constructs, namely, broadcaster attractiveness, the para-social relationship, and bullet-screen interaction, which will be tested to see their direct impact towards viewers’ emotions. In accordance with the existing literature, several factors have proved to influence affective responses and intention to consumer engagement both indirectly and directly [20], and so it was only appropriate to assess the indirect influence as well. Therefore, we considered personal characteristics as the moderating variables between the above-mentioned VGS constructs and positive emotions and empirically tested them to see the impact thereof. In that regard, the study was aimed to derive accurate theoretical research results and subsequently provide more viable marketing or management recommendations for VGS platforms.

In essence, the study proposed the following research objectives to address the gaps: (1) to understand what and how the positive emotions are triggered through VGS features (broadcaster content, functional, and social-facilitation) and how these emotions are associated with engagement; (2) to explore the moderation effect of viewers’ personal characteristics between VGS features and positive emotions.

The research outline goes as follows: in the Section 2, we introduce the theoretical foundation of our study. In the Section 3, we develop our hypotheses. The Section 4 gives the research methodology and the analysis of the results, while the Section 5 discusses the results thereof. The Section 6 presents the subsequent implications together with the limitations of the study, future research, and the conclusion.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Research Background of Video Game Streaming (VGS)

Live streaming has become a worldwide phenomenon: anything from dining to gaming to singing can be broadcasted by anyone through any live-streaming software, and viewers can watch all kinds of live streams at their convenience [10]. Millions of viewers worldwide have specifically turned to video game streaming (VGS) not only for watching purposes but to engage in other activities rendered by the VGS platform as well [8]. The extant literature defines VGS primarily in terms of form and content [21]. With regards to form, VGS is characterized as a new medium that mixes a traditional broadcast and online gaming, such as that seen on Twitch, and other platforms [8,22]. With regard to content, VGS is described as a network broadcast with “online games” as the particular content [23]. There are three key characteristics of video game live streaming that have been discussed in the current literature: first, the broadcaster is the key determinant in VGS contents [14]. They allow viewers to indulge in watching, interacting, and emotional attachment, determining the sustainability of the VGS platform. Second, the activity promotes sociability; that is, live streaming is a form of social media to promote social interactivity [24]. The third aspect is the bullet-screen function of VGS; that is, viewers can comment and view others comments through the screen while watching video games [1].

Researchers have looked into the factors that influence viewers’ continuous viewing intentions [15], broadcasters’ continuous broadcasting intentions [25], and the association of video game genres, content type, and viewer gratifications [8] from a general view of live streaming. Only a handful of studies were primarily concerned with determinants of viewers’ behavioral intention or continuous intention within the VGS context. While exploring that, Sjöblom (2017) [8], Hilvert-Bruce et al. (2018) [16], and Cabeza-Ramírez et al., (2020) [9] all employed the use and gratification theory; Chen & Lin (2018) [26] applied the flow theory; and Xu et al. (2021) [14] utilized the stimulus-organism-response theory. The scarcity of research on antecedents of viewers’ engagement is solely due to the fact that VGS is a new topic that has not been thoroughly explored; as such, it is difficult to draw broad conclusions on the factors that influence viewer engagement. In addition, the existing literature does not necessarily provide a thorough comprehension of the relationship between emotional state and further engagement in the novel context of VGS. Therefore, the current study attempted to add to the body of VGS literature by examining the viewers’ engagement behavior from the perspective of the cognitive-emotion theory, which has not yet been explored.

2.2. Cognitive Emotion Theory (CET)

CET studies how an individual’s cognition influences their emotional states and subsequent behavior [27]. According to the theoretical framework, beliefs and desires are the most fundamental mental states. The theory identifies three sub-processes encountered in the decision-making process, namely, cognition, emotion, and behavior [28,29]. The first stage, the cognitive stage, describes a person’s mental state as a result of a sequence of cognitive processes designed to process information [8]. The cognitive assessment of events or thoughts determines an individual’s mental state during the emotional perception stage, that is, emotions are “products of” beliefs and desires and are integral to action [30,31]. CET suggests that our perception and comprehension of the environment significantly impact our emotions and decision-making. It lays out a basic framework for evaluating and adjusting cognition to change how individuals think, feel, and act. In light of this, prior studies using the CET framework and its assumptions analyzed diverse users’ behaviors; for example, Xu et al. (2020) [17] investigated the role of the emotional state in determining consumers’ behaviors for the global online shopping carnival, while Habib & Qayyum (2018) [32] examined the cognitive components as a prelude to emotional features, which eventually lead to impulsive online purchasing actions. It must be noted that the aforementioned studies are within the general online use and live streaming context; there is still a dearth of knowledge in empirical studies that explain VGS viewers’ engagement behavior from the perspective of CET.

Based on the VGS research context, the application of the CET framework is relevant for three major reasons. Firstly, it has been successfully applied in prior studies involving cognitive and emotional factors explaining social media users’ behavior and live streaming context [13,17,32]. Secondly, it gives a theoretically justified mechanism to integrate various viewer-perceived aspects of the VGS, such as platform content features (e.g., broadcaster attractiveness), functional features (e.g., bullet-screen interactions), and social-facilitation features (e.g., the para-social relationship) [14]. Thirdly, it enables us to understand the viewers’ behavior from the aspects of viewers’ emotional states to have more comprehension of the VGS. Within the VGS context, the features of VGS regarded as antecedents can affect viewers’ cognition process and their emotional state, resulting in consequential behavior [19]. Therefore, this framework helps to identify what features of VGS influence viewers’ emotions and how the emotional states affect VGS viewers’ behaviors [17]. Additionally, this study endeavored to add a meaningful contribution to the existing literature in understanding the decision-making process of VGS viewers’ behaviors based on CET. Moreover, we aimed to extend the existing research by integrating the variable of personal characteristics and examining its moderating effects.

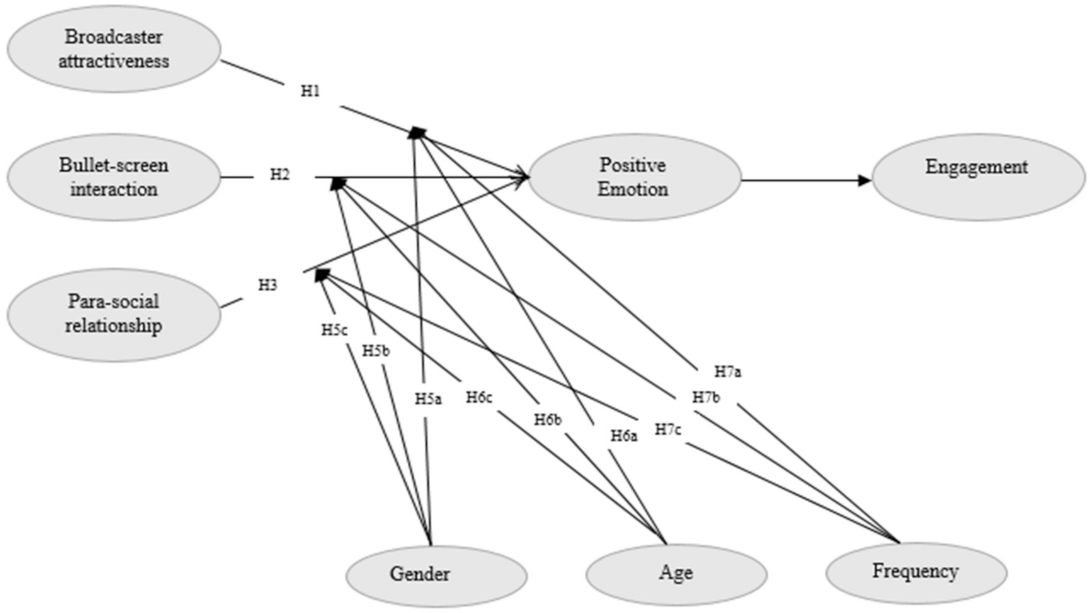

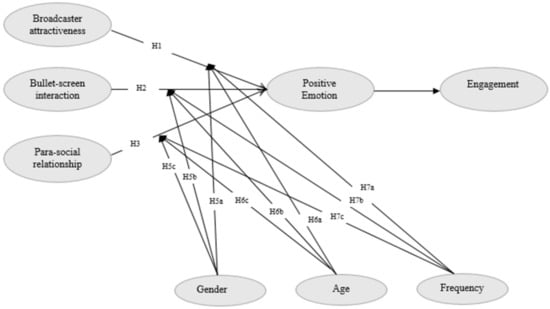

Figure 1 presents a three-staged research model developed based on the cognitive-emotional theory. In the first stage, three cognitions were proposed to reflect the VGS features, namely, broadcaster attractiveness, bullet-screen interactions, and the para-social relationship. On the second stage, that is, the emotional perception stage, this study assumed that the cognition of broadcaster attractiveness, bullet-screen interactions, and the para-social relationship can lead to viewers’ positive emotions such as entertainment and enjoyment. As for the last stage, that is, the behavior stage, we proposed that the three aspects may enhance the viewers’ states of positive emotion, which ultimately lead to their engagement behavior in VGS. Lastly, this study proposed that personal characteristics such as gender, age, and media use frequency can moderate the relationships between the cognitive and emotional stages in the model.

Figure 1.

The research model.

3. Hypothesis Development

This section extensively discusses each of the postulated relationships shown in Figure 1 based on sound theoretical underpinnings, namely, (1) the relationships of broadcaster attractiveness, bullet-screen interaction, and the para-social relationship with positive emotion; (2) the relationship of positive emotion and engagement; and (3) the relationship between personal characteristics (gender, age, and frequency) and broadcaster attractiveness, bullet-screen interaction, and the para-social relationship.

3.1. Broadcaster Attractiveness

The VGS primary content is the broadcaster’s real-time video of his or her game-playing procedure, which allows viewers to watch, engage with, and participate in the VGS. The success of a VGS channel is mostly determined by its broadcaster attractiveness, that is, the attractiveness of a broadcaster determines the number of viewers willing to watch [17]. Viewers are drawn to a broadcaster’s attractive qualities, such as his or her performance, game knowledge, communication skills, charisma, and ability to promote viewer involvement and devotion [33]. As a result, we define broadcaster attractiveness in this study as an individual’s attitude or judgment of a broadcaster’s appeal or the level of a broadcaster’s overall appeal perceived by viewers [34,35].

More often than not, people’s emotional attachment to someone solely relies on personal attractiveness [36]. The pleasant personality and charming traits, for example, may make others feel at ease; the sense of humor can make others laugh and feel enjoyment; the conscientious and sincere attitudes can make others feel appreciated; and their appealing appearance can also leave a positive impression [37]. According to DeGroot et al. (2011) [38], viewers’ judgments of broadcasters are highly influenced by the attractiveness of personal characteristics, and viewers will react both affectively and intellectually to the broadcasters. An endorser’s attractiveness has several beneficial relationships with consumers’ positive emotions, such as arousal, excitement, and enthusiasm [38]. Jin & Merkebu (2015) [39] asserted that the endorser’s physical attractiveness had beneficial relationships with consumers’ positive emotions resulting from appreciation and pleasant behavior towards the product/brand, as they serve to improve its reliability and promote it through live streaming. Similarly, Chi et al. (2011) [40] proposed that celebrities can increase a consumer’s positive impression of a product’s worth, with the promotional impact being larger when their knowledge is high and when they have appealing physical qualities and behavioral traits.

Viewers of VGS watch videos to unwind [8] and to appreciate the entertainment and the flow [26], and broadcasters have a great effect on these emotional gratifications [41]. Naturally, viewers are more likely to develop a good attitude towards the broadcasters who are appealing to them and who fulfill their emotional gratifications and who enhance their state of exhilaration [11,42]. Consequently, if broadcasters are more appealing to VGS viewers, viewers will be more willing to extend the time and frequency of watching the VGS, which could innately enhance the viewers’ cognitive assimilation and induce the viewers to develop positive emotions such as arousal, pleasure, and happiness while watching VGS [43], thus leading us to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Broadcaster attractiveness is positively correlated with positive emotion.

3.2. Bullet-Screen Interaction

VGS has a kind of unique social function, namely, bullet-screen interaction, which integrates two online activities in the virtual space of VGS—texting and video viewing— hence creating a communication environment for both players and audiences [44]. The bullet-screen is an innovative technology that allows viewers to edit and post comments that fly over videos in real-time or watch co-viewers comments whiling watching VGS. It can reflect viewers’ judgments and comments regarding the VGS channel or the broadcasters’ playing process [45]. The viewers’ watching experience is more engaging than watching traditional online videos as the technology provides viewers’ participation in the process of information production [46].

As a kind of innovative and interactive communication technology, the bullet-screen constantly attracts viewers because, most importantly, the sociability feature facilitates viewers’ social interaction in the virtual world [47]. One of the most important elements influencing people’s emotions is social interaction, so an individual’s emotions will undoubtedly be influenced by social interaction even in the online virtual environment, which in turn might affect people’s assessments, emotion, and performance [45,48,49].

Thus, enabled by the interactive media, the bullet-screen not only enhances interactions between co-viewers and broadcasters but also alleviates the excitement, arousal, and other positive emotions [15]. According to Sun et al. (2018) [50], the remarks on the screen demonstrate the audience’s excitement and interest in watching, allowing viewers to engage in real-time conversation. Fang et al. (2018) [45] believe that the bullet-screen can deliver a unique social experience and a sense of social presence. It fosters a sense of immersion and allows consumers to identify with the value and advantages they get from an activity, resulting in a positive emotion while viewing [51]. In addition, Liu et al. (2016) [52] indicate that interactive video viewing methods like the bullet-screen are positively associated with playfulness and allow users to enjoy videos in greater depth.

The bullet-screen interactivity in VGS allows viewers to remark on the VGS and communicate with co-viewers and broadcasters in online dialogues [15,53]. On the one hand, discussing important game abilities and gaming experiences and exchanging perspectives on the game with others, which can provide viewers with a sense of freshness and engagement, enhancing viewers’ social connection. On the other hand, using the bullet-screen allows viewers to participate in the process of information generation while also facilitating viewers’ social presence, ultimately promoting pleasant feelings and affective emotions, such as entertainment [8] and social anxiety release [16]. As such, therefore, we hypothesized the following:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Bullet-screen interaction is positively correlated with positive emotion.

3.3. Para-Social Relationship

The para-social relationship is another feature of VGS, which is referred to as the audience’s mutual awareness of and familiarity with media characters in an illusive sense [1]. The para-social relationship is defined as a kind of relationship between viewers and performers that creates the appearance of intimacy in the same way as “real” interpersonal relationships do [54]. According to Dibble et al. (2016) [55], individuals in para-social relationships believe that virtual people on social media are “genuine friends,” that they are conversing with a good friend and friendly social actor, and that they like having this conformable and intimate relationship.

The friendship-like relationship in a social media platform enhances the reliability, attachment, and loyalty toward the online virtual figure. Additionally, it is an important factor to enhance users’ viscosity and makes them enjoy it since it indicates that users can communicate directly or indirectly online, creating the illusion of being physically present in an artificially constructed virtual world [55]. Several studies evidenced para-social relationship experiences with impacts on Facebook [56], Instagram [57], YouTube [58,59], and bloggers [60]. For instance, Sokolova & Kefi (2020) [61] reason that building a para-social connection with a blogger may increase credibility and attachment, as well as create an emotional link with a blogger. Munnukka et al. (2019) [59] demonstrate that the more audience members participate, the greater their level of the para-social relationship. Furthermore, it will boost credibility judgments and promote favorable views about vloggers. In addition, Brown (2015) [62] indicates that connecting with media personae, such as reading their postings, sending text messages to them, and viewing their videos, would lead to people becoming more emotionally attached to and drawn to the media personae.

Live streaming allows viewers to contact and interact with the broadcasters in a variety of ways. Intimacy between the two parties is fostered when broadcasters reply to viewers’ comments and queries in a prompt and courteous manner and when they pay attention to viewers’ viewing experiences and emotional feelings [15]. In the VGS realm, viewers can have such a relationship with broadcasters by subscribing to their channels and following their social media streams [61]. As broadcasters get to share game strategy suggestions in response to audience inquiries, frequently performing spontaneously, they give viewers a sense of closeness and excitement, and they may also offer their thoughts on the game and their own experiences with viewers. Viewers start to think that they “know” the broadcasters as a result of their integration with them when streaming, chatting, and interacting with them [63], which resultantly develops a sense of virtual connectedness and a perceived relationship with the broadcasters [14]. Therefore, as VGS is a highly interactive phenomenon and a social-friendly interaction context, which provides unique opportunities to its viewers to develop virtual associations and relationships with broadcasters [28]. Such a relationship engenders a sense of intimacy and closeness, which is referred to as a para-social relationship [15]. The intimacy and closeness bring viewers a warm interpersonal connection, thus leading to a positive emotion. As a result, the uniqueness of VGS creates a pleasant atmosphere to induce viewers’ positive emotions and the intention of engagement and so we thus hypothesized:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The para-social relationship is positively correlated with positive emotion.

3.4. Positive Emotion and Engagement Behavior

Emotion is a kind of psychological factor that interacts individuals with the external environment. It refers to how we feel while interacting with the external environment and can be considered as the reaction to a specific situation [57]. According to prior research, positive feelings are characterized as “happy,” and their primary synonyms include glad, joyful, cheerful, satisfied, euphoric, cheery, and delighted [58]. Regarded as a psychological phenomenon, the level of individuals’ emotional experiences has been applied to explain behavioral decision-making. The amount of experienced emotion will affect an individual’s approaching reaction, according to Mehrabian and Russell’s hypothesis [64]. Positive emotions can prompt individuals towards behaviors such as a desire to explore and communicate with others and can make people more optimistic about an expected outcome [65].

According to the emotional theories, emotion can shape people’s decision-making process and behaviors by participating in online communities [59]. In the research of individual behavior, several prior studies have confirmed that there is an association between positive emotions and behavioral tendencies [8,11]. This structure has shown to be robust in many users’ behavioral studies [9,66]; for example, Li & Bin (2017) [67] discovered that consumers’ emotional perception affects their propensity to share marketer-generated material when they engage in social broadcasting. Verhagen & Van Dolen (2011) [27] evidenced how consumers’ behavior such as impulse buying results from decisions influenced solely by emotions. Venkatesh et al. (2015) [68] indicated that consumers who have positive emotions (e.g., happiness) resulting from an online platform are more inclined to keep using it. In the same vein, Shen & Khalifa (2009) [69] also argued that when consumers have favorable emotional reactions, they are more likely to engage in online impulse purchases.

Pleasure, entertainment, and excitement are very important representational forms of sentiment when watching VGS [8]. It is an important aspect of streaming to provide an entertaining media environment. As a kind of streaming format, while watching VGS, viewers will enjoy the online social interaction and feel attracted by the likable broadcasters. Additionally, viewers will feel excited, relaxed, and enjoyable through exploring the advanced technology and experiencing the novelty of the platform. Individuals who feel good emotions such as pleasure and arousal when using social media are more inclined to utilize it more frequently than others [70]. Positive emotion is a predictor of “motivational power” [64]; consequently, viewers who experience positive emotion are energized to engage in a range of approaching behaviors, like VGS involvement. Therefore, in the context of VGS, we assumed that viewers can get the positive emotion while watching VGS and further positively impact their engagement in VGS:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Positive emotion is positively correlated with engagement.

3.5. Personal Characteristics

People’s behaviors and choices on the Internet are mainly directed by their stark differences; the characteristics of users could significantly influence their decision-making process, which tends to be dominated by emotions [27] and the resulting behavioral tendencies. Therefore, understanding an individual’s VGS perception and emotional feedback involves examining the influence of their personal characteristics. Previous studies explored the importance of personal characteristics, such as gender [65], age [17], and usage experience (e.g., using frequency) [29], in determining individuals’ use of social media. Similarly, this study adopted gender, age, and using frequency as the moderators in the context of VGS.

Firstly, gender is considered to be a critical moderating variable in examining user behavior as evidenced by Gan (2017) [71], who affirmed the mediation effects of gender on the relationship between hedonic, social, and utilitarian gratification and the clicking “like” behavior for WeChat users. Another study by Kim et al. (2018) [72] also regarded gender differences to be a significant moderating factor influencing the individuals’ attitude towards social media use. In particular, several studies have explored gender differences in terms of media usage preference in the context of live streaming [10,73,74]. Weiser (2000) [75] found that with regard to Internet use patterns and preferences, males tend to engage in entertainment and leisure activities on the Internet, while females prefer the Internet more for communication and educational purposes, thus highlighting the importance of gender as moderating variable for VGS features and viewer engagement. Long & Tefertiller (2020) [73] argued that males are more likely to have interactions with broadcasters, and their communication with other viewers on the platform is also more active than females. In addition, Todd & Melancon (2018) [74] found women pay more attention to the style, content, and credibility of broadcasters.

VGS provides a novel channel for viewers to engage in entertainment, estimate the attractiveness of broadcaster, and develop para-social interaction with broadcaster and co-viewers via the bullet-screen. Considering that males and females differ in terms of hedonic activities, features of broadcasters [74], communication preferences [75], information presentation [76], etc., gender differences may be worth the investigation especially in VGS since it is rarely explored and plays a significant role. Following the widely adopted approach of gender as a moderating variable [71,72], this study embarked on assessing the underlying mechanism of the moderating effects of gender on the relationships between perceived VGS features (e.g., broadcaster attractiveness, bullet-screen interaction, and the para-social relationship) and emotions; as such, the following hypotheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 5a (H5a).

Gender has a moderating effect on the relationship between broadcaster attractiveness and positive emotion.

Hypothesis 5b (H5b).

Gender has a moderating effect on the relationship between bullet-screen interaction and positive emotion.

Hypothesis 5c (H5c).

Gender has a moderating effect on the relationship between para-social relationship and positive emotion.

Secondly, age has proved to be a significant moderator in studying social media user preferences in accordance with the existent research. Chatterjee (2020) [77] proved the moderating impact of age on the addictive behavior of online social games. The author revealed that young adults are more prone to playing online social games in comparison to mid-age adults. Even in terms of online purchases, younger users tend to have higher purchase intentions compared to older age groups [78]. An additional study by He et al. (2020) [79] also confirmed age to bear mediating effects on the association between digital access and informal social participation.

Xu et al. (2020) [17] also indicated that age difference influences the determinants of usage, frequency, and further interaction in social media. People of different ages pay different degrees of attention to appearance, and young people pay more attention to appearance when using social media [80]; as such, appeasing appearances will result in positive emotions for the younger generation in comparison to the older generation. Young people are more emotional, and they tend to frequently share views and thoughts on social media compared to older people [81]. With reference to the existing literature proving that age can moderate people’s emotions, attitudes, and preferences towards social media and influence how they make their decisions, we, therefore, inferred that different age groups may have different views of the relationships between perceived VGS features (broadcaster attractiveness, bullet-screen interaction, and the para-social relationship) and emotional reactions to VGS. Hence we regard age as a mediating variable and proposed the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 6a (H6a).

Age has a moderating effect on the relationship between broadcaster attractiveness and positive emotion.

Hypothesis 6b (H6b).

Age has a moderating effect on the relationship between bullet-screen interaction and positive emotion.

Hypothesis 6c (H6c).

Age has a moderating effect on the relationship between the para-social relationship and positive emotion.

Thirdly, with regards to media usage, earlier studies have also shown that user experience, such as use frequencies, can have moderating effects on individuals’ attitudes and behaviors in social media. Liu & Bakici (2019) [82] indicated the more frequently people use social media, the more they are likely to share information, generate entertainment, and have social interaction with others, which will eventually affect positive emotions as they get satisfied with the use. The greater amount of experience or the much greater time spent on using various social media tools, the higher the propensity of users to engage with the sites of their interest [83]. People with different usage frequencies differ in terms of social interaction [82], hedonic activities, and usage of communication functions [83], etc. Use frequency differences may be worth the investigation with regard to the linkage between unique features of VGS (broadcaster attractiveness, bullet-screen interaction, and the para-social relationship) and positive emotion. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 7a (H7a).

The frequency of media usage has a moderating effect on the relationship between broadcaster attractiveness and positive emotion.

Hypothesis 7b (H7b).

The frequency of media usage has a moderating effect on the relationship between bullet-screen interaction and positive emotion.

Hypothesis 7c (H7c).

The frequency of media usage has a moderating effect on the relationship between the para-social relationship and positive emotion.

To conclude, prior studies have shed light on the significance of personal characteristics (e.g., age, gender, and use frequency) as moderators while study Internet users’ behavior patterns, attitudes, and emotions [75]. Therefore, the investigation of personal characteristics can provide a useful understanding of a growing body of literature on exploring the CET perspective of the VGS viewers’ behavior [73], and so Hypotheses 5–7 were proposed to better explore the question of “how are the hypothesized relationships different between respondents with different personal characteristics”?

4. Methodology and Findings

4.1. Research Method

4.1.1. Procedure

A web-based survey was performed through a questionnaire to test the hypothesis of the study model and collect empirical data. To examine the research model, the study collected empirical data in 2019 using a widely used web survey website (https://www.sojump.com/ (accessed on 1 October 2021). Before formally answering the questionnaire, we described the research objective and assured that the information provided by respondents in the questionnaire was confidential. In order to improve the quality of the data, we set a question at the beginning of the questionnaire to ask the participants whether they have watched the VGS in the past month; only the users who watched the VGS in the past month could answer the questionnaire. If the respondent answered “yes” to these questions or failed to complete all of the survey questions, the questionnaire was immediately destroyed to ensure the validity of the subsequent data analysis. In order to encourage answering, all responders who completed the questionnaire were offered between 5 and 10 RMB (roughly USD 1–1.5) rewards. The data-collection process via cross-sectional survey should be randomized in targeting the sample frame (e.g., VGS viewers with watching experience), since the purpose was to obtain the survey sample in a natural setting. The robustness of sample data collected in a natural setting should represent a larger population of the targeting users (e.g., VGS users in this study), in order to show the generalizability of the research results [84]. This approach has been widely adopted as the underlying principles of this type of survey research in countless studies in the most reputable journals [84,85,86]. Thereby, following a similar research design in existing studies, this study applied the randomized design in a natural setting to obtain the responses from VGS reviewers.

4.1.2. Survey Participants

The online survey collected 308 valid responses, and the demographic characteristics of the respondents are as shown in Table 1. The gender distribution of the sample comprised 41.56% males and 58.44% females. The distribution of sample gender showed a very similar proportion with many studies in the context of live streaming. In other words, several recent studies adopted a randomized survey design in the targeting samples and suggested a similar portion of male and female distribution in live-streaming users, such as Hou et al. (2020) [10], Chen (2018) [26], and Hu (2017) [15]. Whereas, several studies suggested that male viewers are the majority of VGS viewers, since many viewers are game players who are mostly males [16,87]. We would like to elaborate this discussion in the section on limitations.

Table 1.

Demographic distribution (N = 308).

Regarding age, respondents under the age of 25 accounted for 79.55% of the respondents, implying that viewers under 25 years old are the dominant VGS users in a larger population. As a widely acknowledged observation in existing studies, Shen (2021) [87], Hu et al. (2017) [15], Zhao et al. (2018) [25], and Hou et al. (2020) [10] all pointed out that the majority of VGS viewers are under 25 years old (around 80%). Our finding is consistent with them; in other words, our sample represents the distribution of the large sample. Additionally, most VGS viewers are university students, accounting for 65.30%. Furthermore, regarding watching frequency, we adapted the extreme limit classification of high frequency and low frequency, with watching every day as high frequency and watching less than once a week as low frequency, an approach similar to prior studies such as Chen (2020) [88], Zhao (2020) [89], and Luqman et al. (2017) [90]. The more detailed explanation of the division of comparison groups is provided in the section of structure model analysis (see Section 4.2.3). Our sample showed that there were 30.2% of respondents who stated that they watch VGS every day, and 11.04% of respondents watch VGS less than once a week.

4.1.3. Measurements

The constructs and measurements in this study were mainly adapted from prior literature with several modifications to make them appropriate for the current VGS research context. The items were scored on a five-point Likert scale, with 1 being “strongly disagree” and 5 being “strongly agree”.

The items for measuring broadcaster attractiveness we derived from a study by Liu et al. (2007) [34], while those measuring the viewers’ engagement in VGS through the impact on positive emotion were from the work of Osei-Frimpong (2019) [36]. The measure for bullet-screen interaction was according to Rubin & Perse (1987) [91] and Metiu & Rothbard (2013) [92], and the items for the experience of para-social interaction came from the scales of Hartmann & Goldhoorn (2011) [93]. To account for factors of “positive emotion” exploring the impact on the viewers’ engagement of watching the VGS, we applied Ostrom’s measurement [94]. In addition, the measures of engagement are from the research of Chang & Chuang (2011) [95]. A list of these measurement items is shown in the Appendix A.

In order to increase the validity of our questionnaire material, we also performed expert interviews and a small-scale pilot test. A total of fifteen specialists were asked to take part in the pilot test and make modest changes to the language and appropriateness of the scales. In addition, the questionnaire included attention-check questions (ACQs) such as opposing questions and repeated questions. Researchers have suggested several advantages of including ACQs into the questionnaire. First, ACQs can be applied to identify careless respondents and allow researchers to screen them out prior to conducting analyses to ensure data validity [96]. Second, the respondents’ attitude towards the seriousness of answering the questionnaires is very likely to be influenced by ACQs. Respondents are more likely to answer the questionnaire carefully when the ACQs are included in the questionnaire, since they might presume that paying close attention to the survey item is important and apparently highly valued by the survey designer [97], such that “participants will empathize with the survey administrator’s desire to obtain accurate data” [98]. When attention checks are applied to screen for perfidious careless responses attentive respondents “may view their survey completion as more meaningful” [99].

The questionnaire consisted of three parts. The first part was the description of our objectives and motivation of the research and provided the insurance about their anonymity and privacy for respondents. The second part was about the background and demographic information about respondents, and the last part contained the questions based on the measurements of constructs in our research model.

4.2. Data Analysis

4.2.1. Measurement Model Analysis

In the first phase, we used some indicators to assess the model fit for the research model as shown in Table 2. For a satisfactory model fit, the chi-square value normalized by degrees of freedom (CMIN/d.f) should range from 1 to 3. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) must not be more than 0.08 [100,101]. The comparative fit index (CFI) and the non-normed fit index (NNFI), also known as the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), should be greater than 0.90. In the same manner, the value of the adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) should be more than 0.80 [102]. For the current measurement model, the fit indices (CMIN/d.f = 2.710; RMSEA = 0.067; CFI = 0.913; NNFI = 0.906; AGFI = 0.826;) indicated that the suggested measurement model had a very satisfactory model fit [102,103].

Table 2.

Model fit indices of the measurement model.

In the second phase, the reliability and validity analyses were tested to examine the adequacy of the measurement model. Cronbach’s alpha and the composite reliability (CR) were employed as reliability metrics. Cronbach’s alpha usually gets reported mostly because it is a traditional way to display convergent validity and hence display reliability. In addition, Cronbach’s alpha is a conservative measure, which tends to underestimate reliability. Compared to Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability may lead to higher estimates of true reliability. Reporting both CR and Cronbach’s alpha can enhance the persuasiveness and comprehensiveness regarding the reliability of the measurement model.

As shown in Table 3, the results show CR values all exceeded the required level of 0.7 [107]. Item loadings were used to assess convergent validity, and the average variance was calculated (AVE) and used to assess convergent validity. The square root of each AVE situated in the matrix diagonal must be higher than inter-construct correlations situated outside the diagonal, so as to ensure discriminant validity (see Table 4) [108,109]. The AVE values and factor loadings exceeded the values of 0.5 and 0.7, respectively, thus showing that convergent validity was also satisfied [108]. The model consisted of 16 variables that described five latent constructs: broadcaster attractiveness, bullet-screen interaction, para-social relationship, positive emotion, and engagement. The AVE square root values surpassed the correlation coefficients of all the latent variables, demonstrating discriminant validity, which implies that all constructs in the proposed study model may be ensured (see Table 4) [107].

Table 3.

Reliability and convergent validity.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity and inter-correlations among constructs.

4.2.2. Measurement Invariance

Before testing the statistical significance of the differences in the path coefficients between the groups, it was considered appropriate to conduct the measurement invariance test across the specified groups divided by gender, age, and usage frequency (male vs. female, 25 and below vs. above 25, and high frequency vs. low frequency). The measurement invariance test can ensure the validity of the model and the findings of between-group comparisons based on that measurement [110]. Thus, following the instructions proposed by Hair et. al. [101], we firstly tested for configural invariance and conducted a multi-group analysis on the factor specification without placing any constraints on the parameters between the different group samples. Next, the unconstrained configural invariance model was used to compare with a metric invariant model in which all factor loadings were fully constrained to be equal in both samples [111]. If the constrained model does not significantly impair the fit of the model and the chi-square difference test does not reveal a significant difference, it can be concluded that the measurement model is invariant across two groups [101,111,112].

First, a measurement invariance test for the models associated with age and usage frequency was conducted. For the age of 25 years old and below and the above 25 years old groups, the chi-square difference between the unconstrained model and metric invariance model was not significant (ΔCMIN (Δdf) = 15.565 (11), p > 0.05). It was therefore concluded that the proposed measurement model was applied across the two age groups. As for usage frequency, for the group with high watching frequency (watch every day) and low watching frequency (less than a week), the unconstrained configural model showed an acceptable baseline model, and the chi-square difference between the unconstrained model and constrained model was not significant (ΔCMIN (Δdf) =17.975 (11), p > 0.05), suggesting that factor loadings of both two frequency groups were invariant. Therefore, it was concluded that the proposed measurement model applied across both two groups of age and using frequency. respectively [101].

Second, a similar test was performed to examine measurement invariance for males and females. The results indicated that the chi-square difference test between the unconstrained model and the constrained model did not support full metric invariance (ΔCMIN (Δdf) = 22.358 (11), p < 0.05). Given that, Steenkamp and Baumgartner (1998) [110] indicated that it can be considered acceptable for group comparisons if a model with at least two measurements per construct is invariant. Therefore, we performed a partial factorial invariance analysis for all of the constructs by conducting a path-by-path examination based on the modification indices, aiming to find out which of the loadings differed across groups [101]. The results revealed that only one measurement item of broadcaster attractiveness were non-invariant (ΔCMIN (Δdf) = 12.984 (2), p < 0.05); thus, we relaxed the constraints on the items of broadcaster attractiveness one by one until the results of the chi-squared difference test became statistically insignificant. The results revealed that if we relaxed the equality constraints on BA1, the resulting partial metric invariance model exhibited a comparable fit to the configural model (ΔCMIN (Δdf) = 10 (8.941), p > 0.05). Hence, it can be concluded that the measurement model was considered acceptable for group comparisons.

4.2.3. Common Method Bias

We collected the data through the self-reported questionnaire. CMB is described as “variance is attributable to the measurement method rather than to the constructs the measures represent” [101]. In order to ensure that there was no significant common method bias (CMB) using the cross-sectional survey, we tested the potential CMB using two statistical analysis methods.

First, Harmon’s test was applied to examine if a single factor explaining the majority of covariance existed [101,113]. The results of unrotated principal components factor analysis showed that there was 38.1% total variance, which was less than 50%, indicating the majority of covariance did not exist. Therefore, the test results suggested that there was no problem with CMB in this study.

Second, we applied a common method factor in our research model, with the guidance of Liang et al. [113], Podsakoff et al. [114], and Williams et al. [115]. The CMB can be obtained by comparing the variances of each observed indicator explained by its substantive construct and the method factor. The results are presented in Table 5. It is shown that not only the substantive factor loadings (R12) of each item were much larger than the corresponding method factor loadings (R22), but also most method factor loadings were not significant. In addition, compared to the method factor (R22 = 0.019), the principal constructs (R12 = 0.465) explained a much larger average variance in the model. To conclude, CMB was less likely to be a serious issue for this study.

Table 5.

Common method bias analysis.

4.2.4. Structure Model Analysis

SEM is an appropriate approach for analyzing empirical data in confirmatory research [116]. As a second-generation data analysis tool, AMOS 24.0 was employed in this investigation to investigate the measurement model and structural model using the two-phase approach of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) [117]. Following the technique, we evaluated the fitness of the overall model and empirical data conformity as well as estimated the statistical significance for path coefficients and the degree of significance of the hypotheses in the structural model.

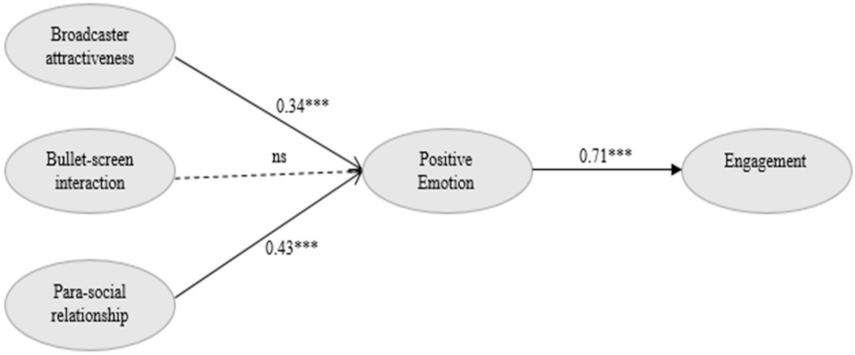

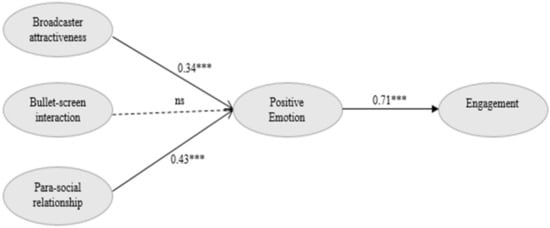

First, the path co-efficiency and its significance level were tested in the basic model for each relationship proposed in the research model, as indicated in Figure 2. The results of the hypothesis testing are also shown in Table 6. These results showed that all of the variables in the study model can adequately explain the development of the dependent variables. Three of the four hypotheses were supported. Specifically, broadcaster attractiveness and the para-social relationship were substantially and positively related to positive emotion and further engagement. In other words, the research results support H1 (β = 0.34, p < 0.001), H3 (β = 0.43, p < 0.001), and H4 (β = 0.71, p < 0.001). However, H2 is not supported by the empirical data. It means the bullet-screen interaction was not significantly associated with positive emotion.

Figure 2.

Results analysis for the research model. Notes: *** p < 0.001; ns: not significant.

Table 6.

Results of the hypothesis testing.

Second, this study evaluated the moderating effects of personal characteristics, including gender, age, and watching frequency. We categorized the data into two according to the three classification methods. First, gender was classified in terms of the male group and female group so to make a comparison between the genders [15,26,73]. Second, Respondents were classified into the age group of below and exactly 25 and the age group above 25. The comparison was based on the statistical results and the distribution of most existing literature in live streaming [10,15,25,87]. In other words, the comparison between the user group of 25 years old and below and the user group above 25 represents the comparison between the majority and minority in the VGS context. Researchers have indicated that a study focusing on a specific research context can contribute precise and detailed knowledge to the literature [84,118]. Thus, we adopted a highly context-related standard (e.g., 25 years old).

Third, watching frequency was classified in two folders of high-frequency group (everyday) and low frequency group (less than a week). This classification was conducted due to two reasons. First, it has been suggested that the upper and lower groups should be selected to conduct the comparison since these groups are most indubitably different with respect to traits in questions [119]. A similar strategy has been widely applied in group classification in leading journals by authors such as Kelley (1939) [119], Chang et al. (2017) [120], Li and Ku. (2018) [121], Chen et al. (2020) [88], Singh et al. (2021) [122], and Xu et al. (2020) [84]. Hence, this study followed the same strategy, using the highest frequency (every day) and the lowest frequency (less than a week) as two comparison groups, aiming to provide the most possible and indubitable differences. Second, the distribution of our sample is in line with existing studies in live streaming and thus is very likely to represent a larger population in watching frequency. For example, the work of Luqman (2017) [90], Zhao et al. (2018) [25], and Zhao & Wang (2020) [89], all stated a similar classification of the “high” and “low” distribution of watching frequency. To conclude, the comparison of high frequency and low frequency was not only in line with the comparison principle and thus produced the most possible and indubitable differences, but it also reflected the actual distribution of the general VGS population.

Based on the three pairs of groups we identified, the moderating effects of gender, age, and use frequency were analyzed. As shown in Table 7, the findings of the multi-group study indicated a substantial difference between gender, age, and watching frequency. Generally speaking, gender only moderates the relationship between broadcaster attractiveness and emotion. Age moderates the relationship between broadcaster attractiveness and emotion and the relationship between para-social relationship and emotion. Watching frequency moderates all the relationships except the relationship between bullet-screen interaction and emotion.

Table 7.

Results of the moderator testing.

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion

This study arose from the necessity to investigate the impacts of critical elements that influence the VGS viewers’ positive emotions as well as how these elements interact to influence the viewers’ engagement behavior in VGS. By using the quantitative analysis approach, the results support the majority of the assumptions in the suggested research model and offer many intriguing findings.

- (1)

- Broadcaster attractiveness positively impacts viewers’ positive emotions in VGS. The outcome is consistent with previous research that indicated that the attractiveness of an endorser could significantly increase the audiences’ positive emotions [123]. Adding to an already established finding by Lu et al. (2018) [124], the research suggests that live stream viewers engage in live streaming for the mere fact of being drawn to streamers’ attractiveness. Similarly, the research result is in accordance with the work of Liu et al. (2021) [124] and Hu et al. (2017), which affirmed the significance of broadcaster attractiveness in stirring viewers’ engagement. Worth noting is that prior research mainly explored broadcaster attractiveness with respect to viewers’ engagement behavior and not their emotions; therefore, our finding extends the literature in this regard, filling the existent gap. In addition, the result is also in line with the observation of the VGS phenomenon. The VGS viewers may be delighted to witness the broadcaster’s outstanding gaming performance, to enjoy the pleasure of conversing with the engaging broadcasters, and to be surprised to learn new gaming techniques. Therefore, the research result also adds empirical support to explaining the phenomenon.

- (2)

- The empirical results suggest that the para-social relationship significantly impacts the viewers’ positive emotion in VGS. Prior studies highlighted the effect of para-social relationships and suggested that they reflected the nature of the relationship between a broadcaster and his or her followers [15]. The feelings of closeness and intimacy naturally lead to viewers’ positive emotions produced by the warm interpersonal relationships with the broadcasters. This result provides an extension to the prior literature by Lim et al. (2020) [125] and Hu et al. (2017) [15] who ascertained the role played by para-social relations between the broadcaster and viewers on consumption behavior and loyalty behavior. Thereby, the empirical evidence was provided to support the conclusion that viewers are more emotionally attached to and identify with broadcasters who provide a more enriched para-social experience.

- (3)

- Bullet-screen interaction does not exert a significant impact on viewers’ positive emotions in VGS. This research result is not in line with existing studies. For example, recent studies mostly confirmed the important role of interactions, such as bullet comments sending [124], danmaku [126], and group chatting via Wechat/QQ [90] in user engagement in the context of game live streaming. Thus, this implied that the bullet-screen feature was bound to have some significant influence on viewers’ emotions; however, our finding was not out of our expectations, as it may result from several reasons. On the one hand, other viewers’ bullet-screen comments may convey some negative emotions, and co-viewers may have conflicting arguments, which may not contribute to positive emotions. On the other hand, viewers often focus on the performance and the interaction of the broadcasters, rather than other co-viewers. Hence the interactions among other co-viewers may not attract the viewers’ attention. Thus, bullet-screen interactions may exert limited impacts on viewers’ emotions. Therefore, this finding expands the scope of bullet-screen interaction within the VGS context. Especially, the results add to those findings as it focuses on the influence of the bullet-screen on the viewers’ emotion.

- (4)

- Positive emotions are positively associated with viewers’ engagement. In addition, positive emotions show a strong predictive power in interpreting viewers’ engagement (coefficient = 0.52 ***). The results suggest that the stronger a positive emotion experienced by a viewer, the more likely he/she would engage in the VGS.

Moreover, this study examined the moderation effects of personal characteristics. (1) Broadcaster attractiveness has a stronger effect on female viewers’ emotions than on males. In other words, female viewers care more about physical appearance and other characteristics of broadcasters. The more attractive the broadcaster is, the easier it is for the female viewers to generate positive emotion and further engage in VGS. Therefore, broadcasters should focus on enhancing their image, specialties, personalities, and streaming styles to attract female users and to stimulate their emotional response. However, as for bullet-screen interaction, this does not make females generate enjoyment. It may be because females’ emotions are more likely to be affected by the negative contents or conflicting views in the bullet-screen stirring annoyance and negative emotions. (2) Broadcaster attractiveness and the para-social relationship both have stronger effects on the emotions of the viewers below the age of 25 than the older viewers. Thereby, younger viewers (below 25 years old) pay more attention to broadcasters, including the attractiveness of broadcasters and the social relationship developed with broadcasters. Hence, the features of broadcasters play a significant role in determining younger viewers’ emotions. Younger viewers can obtain pleasure, entertainment, tension release, or inter-personal intimacy while indulging in the VGS with their preferable broadcasters. Young people are more inclined to establish para-social relationships, and they feel they are interacting with broadcasters and participating in their real life, which further leads to feeling satisfied and enjoyment. (3) Broadcaster attractiveness and the para-social relationship both have stronger effects on the emotions among the viewers with higher watching frequency as compared to less-active viewers (those who watch VGS less than once a week). These findings are in accordance with the observations of the VGS context. The more frequently viewers watch the performance of a broadcaster, the easier it is to discover the uniqueness and charm of the broadcaster. The viewers will be attractive and more willing to participate in the active social interaction and develop a positive emotion in the process to engage the channel of the broadcaster. In addition, the more frequently viewers watch VGS, the more they tend to feel closer and intimate with the broadcaster. They are more likely to establish virtual associations and relationships with broadcasters during this imaginary relationship like the real one, and it can produce a pleasant atmosphere to induce the viewer’s emotions and the intention of engagement. The viewer engagement would enable a sustainable profit model and the growth of VGS. By emphasizing the CET perspective, practitioners can design a better live-medium system to create a more emotionally pleasant environment and to facilitate harmonious inter-personal relationships, thereby contributing to the long-term viability of VGS systems.

5.2. Theoretical Contribution

The study drew several theoretical implications, which are as follows. First and foremost, since VGS is a mushrooming research field, more studies entailing different VGS attributes are required. This particular research expanded the explanatory power of CET within the VGS context. Previous studies mostly employed either the use and gratification theory [10,12], the dual identification theory [15], or the stimulus-organism-response theory [14] while assessing the determinants of viewer engagement in live streaming. The perspective of cognitive emotion theory thus broadens the frameworks that can be used to explain the VGS viewer’s emotions and resulting behaviors. Therefore, all the research results added to the enrichment of the use of the CET model in the VGS context.

Secondly, this research uniquely disintegrated the CET constructs into three VGS features: broadcaster attractiveness as the platform content feature, bullet-screen interaction accounting for the functional feature, and the para-social relationship representing the social-facilitation feature, which is a combination that had not previously been explored. It investigated the influence of the above-mentioned constructs on viewers’ positive emotions. According to the empirical analysis, it was evidenced that three constructs of VGS have a distinct influence on positive emotion with bullet-screen interactivity showing no discernible effect on viewers’ positive emotions. However, the para-social relationship had the greatest significant impact on the viewers’ positive emotions compared to broadcaster attractiveness. Overall, this research performed an in-depth exploration of the antecedents of positive emotion; that is, it identified factors that influence viewers’ emotions and engagement within the VGS context, thus yielding a more comprehensive understanding of viewer–emotion relationships and ultimately contributing to the expansion of the VGS and live streaming literature.

Finally, the internal mechanism of the impact of the VGS features on the viewers’ emotions remains unclear as most studies direct their focus to viewers’ behavior [1,8,9,10,15,41]. This study identified a crucial mediating role of personal characteristics of viewers between VGS features and positive emotions. It examined the impact of VGS features on viewers’ positive emotions from the perspective of personal characteristics. The study provides a clear grasp of how personal characteristics such as age, gender, and media usage (frequency) have moderating effects on viewers’ emotions. Witnessed by our findings, broadcaster attractiveness and para-social relationships have a greater impact on the emotions of younger viewers in comparison to older viewers, and, in terms of gender difference, the same VGS features proved to have a greater emotional impact on female viewers compared to males and on emotions among viewers who watch more frequently than less engaged viewers. Consequently, these results provide a theoretical reference to further explore the emotions and engagement decisions of VGS viewers, which is particularly important because a full comprehension of the dynamics of the viewers’ emotions engagement behavior adds to the VGS development.

5.3. Practical Implications

The results of our research have numerous practical implications for VGS broadcasters and VGS platform managers. First, the study indicates that broadcasters play the most significant role in determining the emotions of viewers and engagement. Many viewers are often attracted by the VGS broadcasters’ excellent gaming skills or likable streaming styles. Hence, VGS platforms may invite professional and reputable game players to join in the streaming events to attract more viewers. In addition, the VGS platform may also initiate cooperation with popular broadcasters with likable streaming styles in other fields (e.g., singing, joking, and e-commerce). The VGS platform may invite them to play games during their streaming to increase the diversity of VGS viewers and thus enhance the popularity of the VGS platform.

Secondly, the VGS platform should create a user-friendly interface and functions for viewers to connect with broadcasters. In addition, the platform may design supporting mechanisms to stimulate such interactions. For example, the platform may sponsor several online and offline activities to allow the viewers to play the games together with their favorite broadcasters and thus obtain more intimate interactions. Thirdly, despite the impact of bullet-screen interaction being insignificant, the VGS platform managers should also pay attention to the bullet-screen because it may convey some negative content, which may affect the views and attitude of viewers towards broadcasters. VGS platform managers should regulate the comments on the platform and block malicious and negative comments.

Finally, broadcasters and managers should focus on the different personal characteristics of the viewers to promote their engagement as it was evidenced that personal characteristics do have moderating effects between VGS features and engagement. The platform should recommend different kinds of broadcasters in terms of content and broadcasting style to satisfy different needs of viewers according to their historical watching records. In retaining the viewers and increasing the usage frequency of viewers, the platform can either send more notifications reminding the viewers to watch the streaming or provide some rewards and incentives to viewers to encourage their engagement.

6. Limitations & Future Research

Although this research produced meaningful value, it is not without its limitations. First, quantitative data were gathered from Sojump, a famous web survey service, with all respondents being Chinese residents. Such a sample will have an impact on and restrict the findings’ generalizability. Future research should use caution when applying the results to other cultures and regions. Further study might aim to broaden the scope of existing research and examine different demographics.

Second, this study applied the cross-sectional survey and examined the self-reported responses; however, viewer engagement habits may differ depending on their experience viewing VGS. As a result, the cross-sectional survey may fail to completely investigate the real behavior, and the change in viewers’ behavior may not be properly noticed. In the future, researchers should consider applying longitudinal research to better examine and validate the model provided in this current study to investigate viewer behavior.

Third, this study only examined the relationships between three constructs and positive emotion. The constructs examined do not consist of a complete list of the possible antecedents. Hence, future studies can thoroughly investigate the influence of other related emotional antecedents of VGS viewers and, in addition, explore more possible behavioral responses and other multiple dimensions of the emotion of the VGS viewers. For example, VGS watching may cause social fatigue and have some negative impacts, which may further lead to some negative behaviors such as addiction, depression, and so on.

In addition, the research only focused on the personal characteristics of gender, age, and usage frequency. Future research can study more personal factors such as educational level and the occupation of viewers and how they can influence the usage of VGS. In addition, the practical implications suggested in this study can be applied to the general live streaming context, while future studies may focus on expanding the managerial suggestions from the perspective of VGS. Finally, we would like to indicate the possible sample bias in this study, though we have endeavored to improve the data quality. It seems that the gender distribution of our sample is in line with most of the live streaming studies, such as social streaming and e-commerce streaming. However, several studies suggested that male viewers are the majority users of VGS. For example, the Newzoo report [127] suggested that female viewers are 44% in 2019 via the mobile VGS platforms, and Hilvert-Bruce et al. (2018) [16] claimed that most of their respondents were males (95.6%). A similar proportion was suggested in Shen’s work (2021) [87]. The distribution of our data might be due to both the data collection channel adopted and the total number of empirical data. Hence, we would like to indicate this limitation and suggest future studies to collect data via the channel specialized in VGS and target more VGS male users. In addition, researchers should be cautious to apply the results to the VGS, which are mostly welcomed by male viewers.

7. Conclusions

The unprecedented global expansion of VGS has motivated this research to investigate the antecedents and processes influencing the engagement behavior of viewers. Employing the cognitive emotion behavior theory as the theoretical basis, this study at-tempted to identify the behavior of VGS viewers by integrating it into a research model, which was then tested using structural equation modeling and quantitative data.

This study focused on the individuals’ cognition about the evolving VGS context based on three unique and critical features of VGS: the broadcaster feature (broadcaster attractiveness), the technological feature (bullet-screen interactions), and the social feature (the para-social relationship). Furthermore, this work significantly expanded the theoretical implications in the VGS and CET literature. The empirical results supported and largely verified the significant correlation between the underlying factors of the research model in this study. Furthermore, the findings demonstrated how important viewers’ emotional states may be in influencing their engagement behavior. We believe that the comprehensive and precise implications offered to VGS researchers and platform practitioners will aid in the exploration of more effective methods to further enhance viewer active participation and the growth of VGS.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.-Y.X. and Q.-D.J.; methodology, X.-Y.X., W.-B.N., and L.-W.L.; software, Q.-D.J. and L.N.; validation, X.-Y.X. and. L.N.; formal analysis, Q.-D.J.; data curation, Q.-D.J.; writing—original draft preparation, X.-Y.X. and Q.-D.J.; writing—review and editing, L.N.; supervision, W.-B.N. and L.-W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by: 1. Shaanxi Philosophy and Social Sciences Major Theoretical and Realistic Research Project, Research on the Construction of Distribution Channels of Shaanxi Characteristic Agricultural Products “Agricultural Consumers,” Project No: 2021DN0318. 2. Xi’an social science planning fund project, research on high quality development countermeasures of digital village in Xi’an, Project No: JX50. 3. Academic Research Projects of Beijing Union University (No.SK70202102; JS10202006).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Measurements.

Table A1.

Measurements.

| Constructs | Item | Questions | Loadings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broadcaster attractiveness | BA1 | I think that the personality of broadcaster is very attractive. | 0.792 | [116] |

| BA2 | I think that the broadcaster has an attractive skill of playing games. | 0.771 | ||

| BA3 | I think that the game streaming style of the broadcaster is attractive. | 0.705 | ||

| Bullet-screen interaction | BSI1 | When watching VGS, I can exchange and share opinions with the broadcaster or other viewers through the bullet-screen easily. | 0.865 | [26] |

| BSI2 | When I am watching VGS, I can ask the broadcaster or other viewers question about games through the bullet-screen. | 0.779 | ||

| Para-social relationship | PSR1 | In the VGS, I feel as though the broadcaster and I are friends. | 0.811 | [80,81] |

| PSR2 | When I am watching the VGS, I feel a sense of we-ness (togetherness) with the broadcaster. | 0.798 | ||

| PSR3 | I feel as though the broadcaster cares about my responses during the VGS. | 0.707 | ||

| Positive emotion | While watching VGS, I feel … | [117] | ||

| PE1 | Happy | 0.878 | ||

| PE2 | Excited | 0.760 | ||

| PE3 | Joyful | 0.800 | ||

| PE4 | Arousal | 0.803 | ||

| Engagement | E1 | I engage in VGS activities. (e.g., bullet screen interaction and gift-giving). | 0748 | [118] |

| E2 | I present my opinions during watching VGS. | 0.803 | ||

| E3 | I spend time and effort engaging in watching VGS. | 0.823 | ||

References

- Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, J. A Systematic Review of Literature on User Behavior in Video Game Live Streaming. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNNIC. The 47th Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development; China Internet Network Information Center: Beijing, China, 2021; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Xu, X.; Zhao, K.; Xiao, L.; Li, Q. Understanding the Complexity of Regional Innovation Capacity Dynamics in China: From the Perspective of Hidden Markov Model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtonen, M. The environmental-social interface of sustainable development: Capabilities, social capital, institutions. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 49, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Weng, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhao, K. Self-deprecation or self-sufficient? Discrimination and income aspirations in urban labour market sustainable development. Sustainbility 2019, 11, 6278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, M.; Lee, S.W. Factors Affecting the Popularity of Video Content on Live-Streaming Services: Focusing on V Live, the South Korean Live-Streaming Service. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten Key Digital Trends for 2020: What Marketers Need to Know in the Year Ahead. Available online: https://www.emarketer.com/content/ten-key-digital-trends-for-2020 (accessed on 25 June 2020).

- Sjöblom, M.; Hamari, J. Why do people watch others play video games? An empirical study on the motivations of Twitch users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 75, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza-Ramírez, L.J.; Sánchez-Cañizares, S.M.; Fuentes-García, F.J. Motivations for the Use of Video Game Streaming Platforms: The Moderating E ff ect of Sex, Age and Self-Perception of Level as a Player. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2020, 17, 7019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, F.; Guan, Z.; Li, B.; Chong, A.Y.L. Factors influencing people’s continuous watching intention and consumption intention in live streaming: Evidence from China. Internet Res. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, I.O.; Papavlasopoulou, S.; Mikalef, P.; Giannakos, M.N. Identifying the combinations of motivations and emotions for creating satisfied users in SNSs: An fsQCA approach. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.L.; Lin, J.C.C.; Miao, Y.F. Why Are People Loyal to Live Stream Channels? the Perspectives of Uses and Gratifications and Media Richness Theories. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Chen, L.; Su, Q. Understanding the impact of social distance on users’ broadcasting intention on live streaming platforms: A lens of the challenge-hindrance stress perspective. Telemat. Inform. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.Y.; Luo, X.R.; Wu, K.; Zhao, W. Exploring viewer participation in online video game streaming: A mixed-methods approach. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 58, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y. Why do audiences choose to keep watching on live video streaming platforms? An explanation of dual identification framework. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilvert-Bruce, Z.; Neill, J.T.; Sjöblom, M.; Hamari, J. Social motivations of live-streaming viewer engagement on Twitch. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 84, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wang, L.; Zhao, K. Exploring determinants of consumers’ platform usage in “double eleven” shopping carnival in china: Cognition and emotion from an integrated perspective. Sustainbility 2020, 12, 2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]