Abstract

The prevailing environmental and social challenges worldwide require comprehensive and sustainability-oriented changes in central areas of society—endeavors that call for more sustainability-oriented innovations. Sustainability can be understood as a megatrend within our society comprising sustainability-oriented macro trends such as Agricultural Innovation, Circular Economy, or Clean Tech. In line with this conceptualization, the current paper analyzes to what extent different types of organizations, such as startups and established companies, have been tackling sustainability-oriented macro trends and how much they have been focusing on sustainability-oriented innovation activities within their organization types. For the study, 758 organizations from the Trendexplorer database were examined through univariate and bivariate analyses. The results underscore that sustainability can be perceived as a key driver of structural change by illustrating that different organization types focus on multiple yet diverse sustainability-oriented macro trends simultaneously while concentrating on a specific type of innovation, whereby all three types of innovations (technological, marketing, and product and service innovations) can be integrated.

1. Introduction

Due to the increasing number of environmental and social challenges that are emerging worldwide (e.g., climate change, energy demand, nutrition), comprehensive and sustainability-oriented changes in central areas of society are needed—endeavors that emphasize the need for innovations [1]. Considered a domain that combines economic, ecological, and social dimensions [2], sustainability can also be perceived and understood as a megatrend [3,4].

According to Mittelstaedt et al. [4], megatrends are “complex combinations of economic, political, cultural, philosophic, and technological factors” (p. 254), “broader in scope, longer in duration and more impactful in scope than normal trends” (p. 260), and “extensive in their impact” (p. 255) by “tend[ing] to shape all aspects of society” (p. 254). They “are embedded in the contexts of their time” (p. 260) “as a product of the residue of previous megatrends” (p. 254). Furthermore, sustainability is the fundamental key to changing the current business world [5]; it is also the driver of innovations. Concrete manifestations of the sustainability megatrend are apparent in our society in the form of different sustainability-oriented macro trends that aim to create sustainable solutions for these numerous challenges. The six sustainability-oriented macro trends are as follows: (1) Agricultural Innovation, (2) Circular Economy, (3) Clean Tech, (4) Energy Harvesting, (5) Ethical Consumption, and (6) Zero Waste [6].

“[M]assive change[s] in products, services, processes, [technologies], marketing approaches, and the underlying business models which frame them” [5] (p. 195) are necessary to meet increasing environmental and social demands. However, it is important to also consider the opportunities that can arise from such changes [5]. Due to new innovative and more sustainable energy technologies, products and services, and alternative working concepts of organizations, “a new era of economic development” [5] (p. 195) may arise. In the long run, “transformative innovation[s]” [1] (p. 1) or “radical and systemic innovations” [7] (p. 1) will be needed for more sustainable development. Economic actors such as companies and startups as well as other organization types, including non-governmental organizations (NGOs), need to align themselves with sustainability to survive in the market and to contribute to such a systematic change in society [5].

Hence, innovations are extremely important in order to integrate more sustainability into our social system. The debate pertaining to the relationship between sustainability and innovation is also increasingly being taken into account in academic literature (e.g., [8,9]). Various types of sustainability-oriented innovations have already been identified (e.g., [10,11]). However, the questions of whether and why different types of organizations tend to focus on specific sustainability-oriented macro trends remain unanswered. Therefore, this paper aims to answer the first research question: Do different types of organizations tend to focus on one or more than one specific sustainability-oriented macro trend? Additionally, we address the second research question: Do different organization types tend to focus on a specific sustainability-oriented innovation type? To answer the two research questions, the Trendexplorer database, which is a commercial database for trends and innovations [12], is utilized. Aside from classifying innovations into mega, macro, and micro trends, this database provides daily updated insights into a wide range of areas of trends and innovations. The final dataset is composed of 758 micro innovations, also called micro trends, driven by organizations such as startups, established companies, research, and public institutions, as well as NGOs/non-profit-organizations (NPOs).

First, the results show that sustainability can be perceived as a key driver of structural change by illustrating that different organization types focus on different types of sustainability-oriented macro trends. Notably, Clean Tech is one of the most dominant macro trends in three of the four organization types. Furthermore, the micro innovations driven by different organization types usually address multiple macro trends simultaneously. Second, the paper illustrates in more detail the innovation activities of different types of organizations within the sustainability macro trends. We show that each organization type usually focuses on a specific type of innovation. In particular, sustainability-oriented product and service innovations, as well as sustainability-oriented technological innovations, play more dominant roles compared with sustainability-oriented marketing innovations.

These two main contributions can promote theorizing on the relationship between organization types and sustainability-oriented macro trends, as well as specific innovation types, to encourage future empirical studies in this field.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Sustainability-Oriented Innovations

To deal with the prevailing global environmental and social challenges and to attain enhanced sustainability in society and in the economic system, sustainability-oriented innovations are urgently needed [1,13]. According to Hansen et al. [10], sustainability-oriented innovations can be defined as “innovations which are individually perceived as adding positive value to sustainable development” (p. 704). Sustainability-oriented innovations aim to exert a positive influence on three dimensions of sustainability: a positive economic dimension (e.g., cost savings), a social dimension, and an environmental dimension for society in general (e.g., reduced pollution) [13].

By fostering sustainability-oriented innovations within a company (or in other organization types), a higher diversification of more sustainability-oriented customer and market segments can be reached [10]. Furthermore, new and more sustainable technologies can also be seen as sustainability-oriented innovations [14]. Notably, sustainable entrepreneurship [15] and the creation of sustainability-oriented innovations can not only be pursued and realized by innovative startups but also by established companies [13,16] and other types of organizations, such as NGOs or NPOs [16].

2.2. Sustainability Megatrend and Sustainability-Oriented Macro Trends

Opportunities for sustainability-oriented innovations can be found within the sustainability megatrend and its different macro trends. According to Mittelstaedt et al. [4], megatrends are “complex combinations of economic, political, cultural, philosophic, and technological factors” (p. 254), “broader in scope, longer in duration and more impactful in scope than normal trends” (p. 260), “extensive in their impact” (p. 255) by “tend[ing] to shape all aspects of society” (p. 254), and “are embedded in the contexts of their time” (p. 260) “as a product of the residue of previous megatrends” (p. 254).

In contrast to megatrends, macro trends or meso trends can be defined as “changes in specific domains of society […, that] are easier to identify than mega trends […, that] are visible in multiple sectors, industries, markets, groups, regions, and countries and [that] are better able to adjust themselves to specific circumstances than mega trends” [17] (p. 4). Accordingly, macro trends can be perceived as “concrete variations of a mega trend” [18]. There are six sustainability-oriented macro trends within the sustainability megatrend: (1) Agricultural Innovation, (2) Circular Economy, (3) Clean Tech, (4) Energy Harvesting, (5) Ethical Consumption, and (6) Zero Waste [6].

(1) Agricultural Innovation includes new methods of cultivation in the food sector [19], such as vertical farming or data-based precision farming techniques for agricultural purposes [20]. Innovations in the agricultural sector are often focused on “technological innovations or newly developed cropping or husbandry practices” [21] (p. 630). Notably, agricultural innovations are becoming more attractive and are generating substantial market shares [22].

(2) Circular Economy can be defined “as a regenerative system in which resource input and waste, emission, and energy leakage are minimized by slowing, closing, and narrowing material and energy loops. This can be achieved through long-lasting design, maintenance, repair, reuse, remanufacturing, refurbishing, and recycling” [23] (p. 759). Hence, a Circular Economy aims to realize economic, environmental, and social benefits simultaneously [24]. The Circular Economy macro trend is eliciting more attention in politics and business contexts [25] possibly due to the decrease of available resources in the environment and the current end-of-life production and consumption system in modern societies [26].

(3) Clean Tech (also known as Clean Technology) “refers to any product, service, or process that delivers value using limited or zero nonrenewable resources and/or creates significantly less waste than conventional offerings” [27] (p. 2). It comprises sectors such as “advanced materials, agriculture & forestry, air and environment, biofuels & biochemicals, biomass generation, conventional fuels, energy efficiency, energy storage, fuel cells & hydrogen, geothermal, hydro & marine power, nuclear, recycling and waste, smart grid, solar, transportation, water and wastewater, and wind” [28] (p. 86).

(4) Energy Harvesting “refers to harnessing energy from the environment or other energy sources” [29] (p. 443) and “converting it to usable electrical energy” [30] (p. 505). It can be seen as a way of bolstering renewable energy systems [31]. Energy harvesting is gaining more importance in theory and practice due to the increasing demand for local wireless power supply systems based on regenerative energy sources [32]. Energy harvesting methods comprise mainly solar energy (e.g., photovoltaic technology), thermoelectric energy (e.g., temperature differences), piezoelectric energy (e.g., mechanical motion, kinetic energy, vibration, or pressure), electromagnetic energy (e.g., electromagnetic radiation), radio frequency (e.g., radio frequency technology), acoustic waves (e.g., acoustic technology), or even geothermal energy (e.g., geothermal technology) [31,32,33].

(5) Ethical Consumption can be defined as a “conscious and deliberate choice to make certain consumption choices due to personal and moral beliefs” (Crane and Matten, 2003, p. 2 cited after [34] (p. 401)). When selecting and deciding on a specific product, moral aspects such as the fair and sustainable production of consumer goods play an increasingly central role [35]. Ethical consumption can only be realized if the consumption and production systems change accordingly with consuming and producing more socially and environmentally friendly goods. Another way to realize ethical consumption (and, concomitantly, ethical production) is by changing or adapting companies’ “business models from manufacturing goods to supplying services that meet consumers’ needs” [22] (p. 473). These innovations often exert a positive influence on the environment [22]. Given the advancements in information technology [22], the number of sharing possibilities in innovative production–consumption systems is also growing [22]. By using and consuming products and services in a shared way with other people, new markets can emerge [22].

(6) Zero Waste can be defined as “a worldwide movement that motivates changes in design that make it possible to disassemble and recycle products” [36] (p. 124). The aim of Zero Waste is the reduction or even avoidance of “unnecessary or unwanted waste from a product at any stage of its lifecycle” [36] (p. 124). It “is primarily based on cleaner production, waste management, reduction of unnecessary consumption, and effective utilization of waste materials” [37] (p. 236). Products and services should be created and designed for usability in the long term, including aspects such as “avoiding, reducing, reusing, redesigning, regenerating, recycling, repairing, remanufacturing, reselling, and redistributing waste resources” [36] (p. 124). Accordingly, the macro trend Zero Waste aims to reuse all products and/or materials over and over so no landfill waste will be produced, thus exemplifying the adage, “In nature, ‘everything has its use’” [38] (p. 200).

2.3. Sustainability-Oriented Micro Trends or Micro Innovations

All six sustainability-oriented macro trends can be detected by small and concrete changes and micro innovations in society, which are also called micro trends [17] (p. 4). Micro trends or micro innovations are “new, intelligent, leading-performance, and structure-changing innovations. They are the first concrete signs of emerging trend movements—the macro and mega trends” [39]. Micro innovations can comprise innovative and future-oriented technologies, creative new ways of marketing concepts and strategies, and innovative, progressive products and services [17,39]. They are represented by diverse projects of organization types such as startups, established companies, research and public institutions, and NGOs/NPOs. Regarding the sustainability megatrend, the micro innovations comprise cleaner and more sustainability-oriented technological innovations, more sustainability-oriented marketing innovations, and more sustainability-oriented product or service innovations.

(1) Sustainability-oriented technological innovations are defined as innovative, green, or more sustainable technologies that entail “sustainable resource management; cleaner technologies; benign substitution of hazardous substances; bionics, biomimicry; […]; circulatory economy; [… or even] purification technology in emission control; and waste processing” [40] (p. 1980). They can either focus on developments in technology themselves, or they can be used to create new product and service innovations [17] (p. 4).

(2) Sustainability-oriented marketing innovations can be defined as “the implementation of a new marketing method involving significant changes in product design or packaging, product placement, product promotion, or pricing” [11] (p. 49) and, accordingly, the creation and use of innovative new “marketing tools” [41] (p. 116). Sustainability-oriented marketing innovations aim to search for new markets [42], “the growth or improvement of market share, the inclusion of products in new customer groups, and the inclusion of products in new geographical markets” [42] (pp. 694–695). The creation of such marketing innovations is gaining more importance in practice, especially in combination with the development of new sectors and industries [41]. In the academic literature, marketing innovations have not played an important role yet [41].

(3) Sustainability-oriented product and service innovations comprise radically or incrementally innovative products and/or services [43]. Generally, product innovations can be defined as “the introduction of a good or service that is new or significantly improved with respect to its characteristics or intended uses. This includes significant improvements in technical specifications, components and materials, incorporated software, user friendliness, or other functional characteristics” [11] (p. 48). Aside from product innovations, service innovations also exist. Toivonen and Tuominen [44] define service innovation as “a new service or such a renewal of an existing service which is put into practice and which provides benefit to the organization that has developed it; the benefit usually derives from the added value that the renewal provides the customers. In addition, to be an innovation, the renewal must be new not only to its developer, but in a broader context” (p. 893). More generally, a service innovation can comprise “a new product, process, or service that is significantly different from previous offerings” [45] (p. 2866). All types of organizations are service-oriented to some extent [46]. Therefore, service innovations may play an important role in the survival of organizations in the long run. Aside from pure product innovations and pure service innovations, a combination called “product–service system (PSS)” also exists [47] (p. 237). Notably, PSSs are gaining more importance in the field of sustainability [10]. The main focus of PSSs in organizations is the combination of products and services to provide “functions rather than products” [48] (p. 50). Accordingly, companies or other organization types change their “business models from manufacturing goods to supplying services that meet consumers’ needs” [22] (p. 473). PSS innovations come with numerous positive sustainability impacts (e.g., changing the common production and service systems or changing the consumption systems from traditional “ownership to use [of] or access [to]”) [22] (p. 473). These impacts lead to a reduction of the resources needed, a more sustainable use of products, and a “dematerialization” [22] (p. 473) of society.

2.4. Organization Types

An economy is typically composed of (1) profit-oriented startups and (2) established companies, as well as (3) public organizations including research and public institutions that are supported or owned by the state and (4) non-profit-oriented organizations such as NGOs/NPOs [49].

(1) Sustainability-oriented startups are young, innovative, established companies that have a maximum age of 3.5 years [50]. Startups can be perceived as “potential candidates offering radical solutions [and innovations] to the challenges of sustainability” [48] (p. 50). They follow a “pronounced value-based approach” [51] (p. 487) with the intention to implement ecological and social change processes in society. Therefore, startups can be perceived as a major force in the transition toward heightened sustainability [52,53].

(2) Customers’ and stakeholders’ increasing sustainability demands compel established companies to incorporate more sustainability into their business activities. They illustrate their willingness to consider and fulfill these changing requirements with positive effects on their competitiveness [13,51].

(3) Public research institutions comprise universities and research institutes [54] that are driven by the public sector’s intensifying focus on political innovation strategies to integrate sustainability into research funding schemes [55]. As a consequence of this funding, public research institutions in particular may be seen as key drivers of innovativeness throughout society [54], especially in the context of sustainability.

(4) The non-profit sector includes organizations that are not aiming for profit maximization [56] such as NGOs [49] and NPOs [57]. NGOs are “private, not-for-profit organizations that aim to serve particular societal interests by focusing advocacy and/or operational efforts on social, political, and economic goals including equity, education, health, environmental protection, and human rights” [58] (p. 466). Specifically, NGOs affect sustainable development by partnering with key stakeholders [59]. Meanwhile, NPOs are private organizations with social missions [60]. NGOs and NPOs can provide added value for greater sustainability by acting as supporters in the social system [61] and by creating social value [57]. It is worth mentioning that NGOs/NPOs are becoming more innovative in terms of their structures and marketing purposes to satisfy their stakeholders’ needs and to gain sufficient funding sources [49,57].

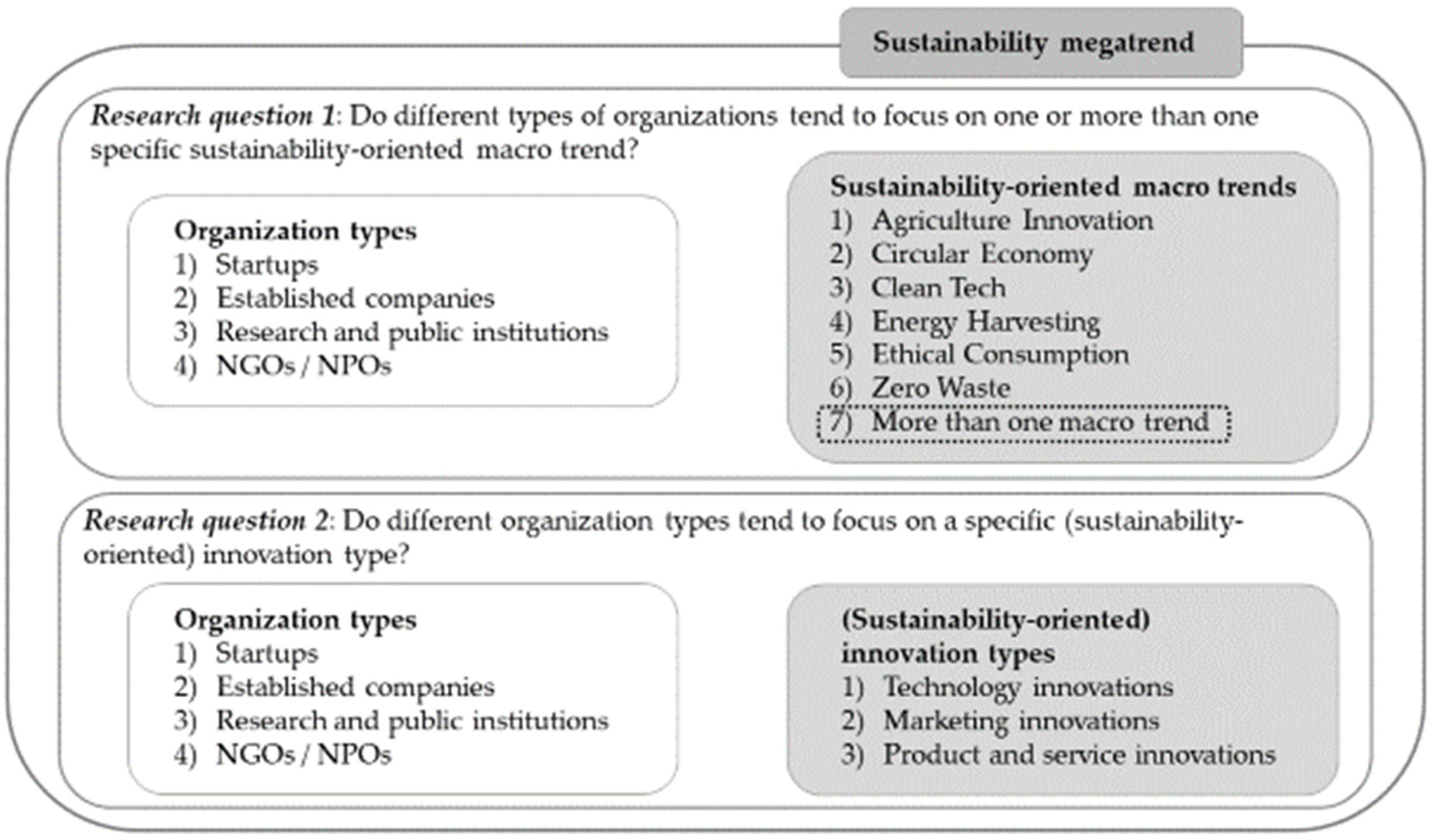

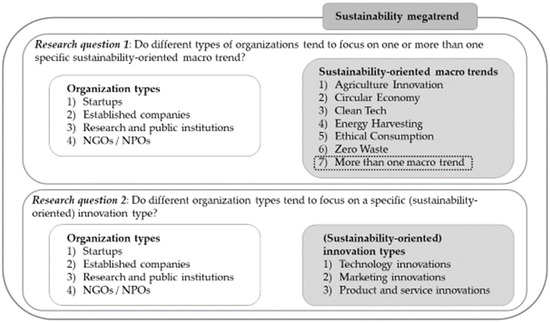

To better understand how different organization types may contribute to the sustainability megatrend, a detailed examination of the various sustainability-oriented macro trends and the different types of sustainability-oriented innovations is warranted. Only then will it be possible to illustrate the innovation efforts of different organization types and identify where unused opportunities may lie to realize a structural change toward a more sustainable society. The present paper addresses this topic by studying 758 micro innovations (cases) driven by different organization types within the sustainability megatrend. Figure 1 provides an overview of the overall research analysis.

Figure 1.

Overall research analysis.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

The analysis is based on a dataset of 758 micro innovations (cases) driven by different organization types addressing the megatrend of sustainability; they were extracted from the Trendexplorer database provided by Trendone GmbH located in Hamburg (Germany), a commercial database for trends and innovations [12]. In order to identify the corresponding micro innovations during the period of initial data collection in June 2019, the researchers selected the most recent 1026 cases. After cleaning the data from duplicates, 1020 cases (data status as of June 2019) addressing the corresponding megatrend of sustainability remained in the sample. As part of a further data collection effort from September 2019 to January 2020, the researchers excluded every micro innovation for which no founding year of the organization type could be found via extant research and for which no innovation type was provided via the dataset of Trendexplorer. Furthermore, identified cooperations between two or more organization types were excluded from the dataset because no reasonable founding year was available, resulting in a final sample size of 758 micro innovations. Besides information such as names, websites, sustainability-orientated macro trends, and innovation types, other information that were not provided by the database of Trendexplorer, such as the organization types, the founding years, and the regions of the micro innovations, were integrated and coded by the researchers. The founding years were integrated by using the Crunchbase database as an additional data source. For the regions of the micro innovations, the country information of each micro innovation was extracted from the Trendexplorer database in a first step (containing a total number of 64 different countries) and coded and recategorized/reclustered by the researchers into five geographic regions: (1) Africa, (2) Americas, (3) Asia, (4) Europe, and (5) Oceania [62]. For the data preparation, a multi-stage interrater reliability procedure was carried out by the researchers.

In order to identify the variables for the analysis, a codebook was developed by the researchers [63]. The theory-based codebook [64] was used by two researchers for the coding process, which included all aspects of the ongoing assessments and the following adoptions of the codebook and of the appropriate coding process [63]. The researchers focused on the principles of simplicity and robustness in creating and adapting the codebook [65]. The created codebook included all variables, their definitions, and the codes used in the coding process. For each variable, separate coding rounds were conducted by the researchers. In the first step, a subsample of more than 10% of the whole sample (76 organizations) was randomly chosen for the first coding; this was later excluded in the coding process of the entire sample for the investigation. The interrater reliability according to Cohen’s kappa [66] was measured after every single coding round. If there was a high disagreement, the codebook was adapted, and the researchers performed a re-coding of the subsample. The coders took sufficient interruptions between the coding rounds to avoid acclimation with the data. To reach an adequate interrater reliability, an average of 1.5 coding rounds was necessary with a Cohen’s kappa of 0.87. Then, two researchers coded the full sample separately.

3.2. Variables

The first variable constitutes the organization type. Startup is a binary (categorical) variable indicating whether the organization is a startup founded in 2016 or later (1) or not (0). Established company is a binary variable indicating whether the organization is a company founded before 2016 (1) or not (0). Research and public institution is a binary (categorical) variable indicating whether the organization is a research institution or a public institution (1) or not (0). NGO/NPO is a binary (categorical) variable indicating whether the organization is an NGO/NPO (1) or not (0).

The second variable, sustainability-oriented macro trend, is a nominal variable with the following subcategories: (1) Agricultural Innovation, (2) Circular Economy, (3) Clean Tech, (4) Energy Harvesting, (5) Ethical Consumption, and (6) Zero Waste. Due to the possibility that a micro innovation driven by a specific organization type may encompass more than one sustainability-oriented macro trend (subcategory (7) More than one macro trend), the researchers included those cases for the data analysis.

The third variable, sustainability-oriented innovation type, is a nominal variable with the following subcategories: (1) technological innovations, (2) marketing innovations, and (3) product and service innovations.

The fourth variable constitutes the regions where the different organization types and their micro innovations are located in order to account for country-specific differences. The five geographic regions are as follows: (1) Africa, (2) Americas, (3) Asia, (4) Europe, and (5) Oceania [62].

The fifth variable is the natural logarithmic age (ln_age) (continuous) of the organization types.

3.3. Analytical Approach

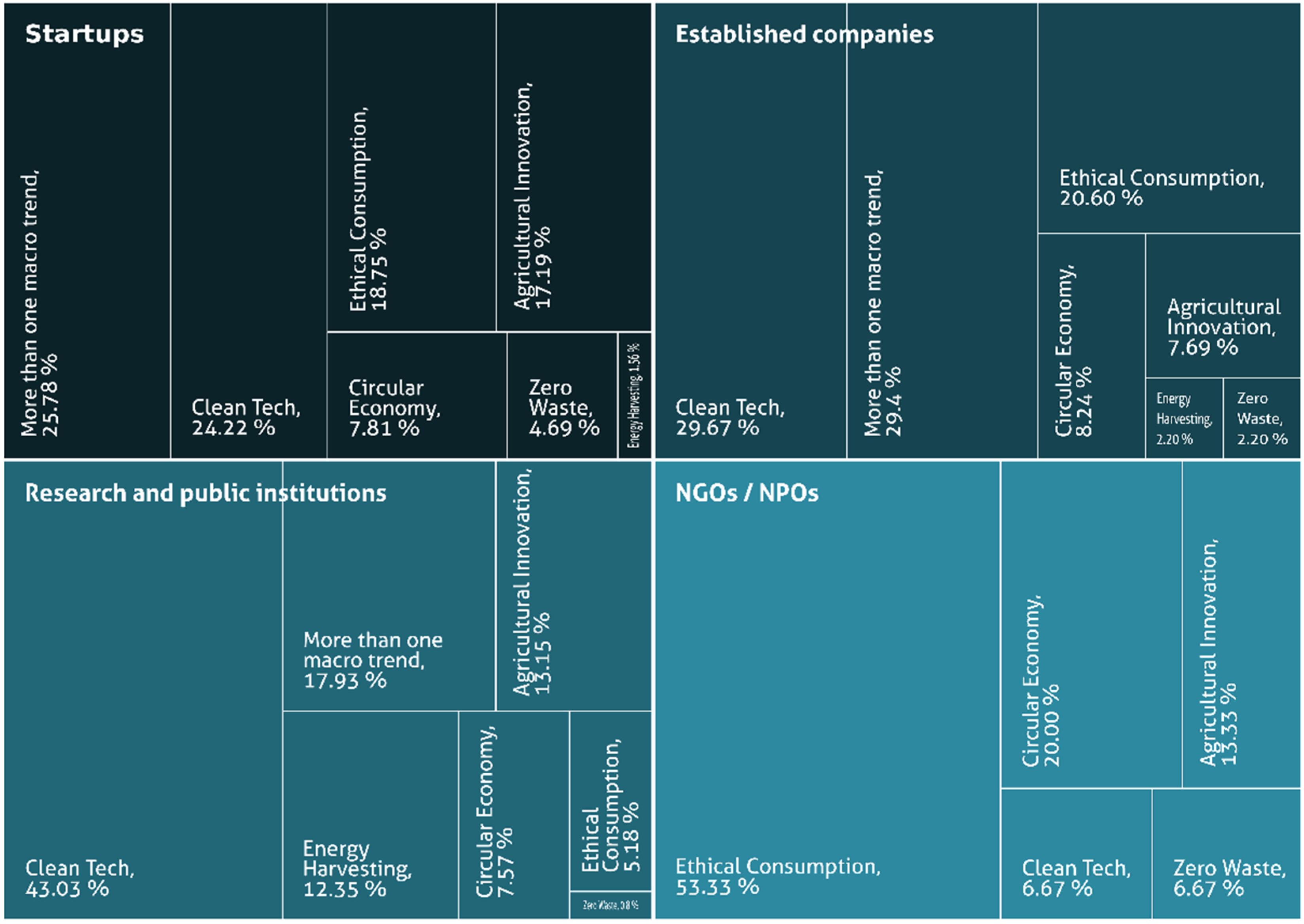

For Analysis 1 (see Figure 1), we explored the relationships between the different sustainability-oriented macro trends and the different types of organizations; for Analysis 2 (see Figure 1), we explored the relationships between the different (sustainability-oriented) innovation types and the different organization types. We summarize the bi-variate analyses in Figure 2 and Figure 3. Both not only provide the numerical results but also give a graphical representation of how the innovations are distributed across organization types, innovation types, and macro trends.

Figure 2.

Organization types and sustainability-oriented macro trends. Note: Chi2 = 116.53 (p = 0.000), Cramer’s V (0.226, p = 0.000), and contingency coefficient CC (0.365, p = 0.000).

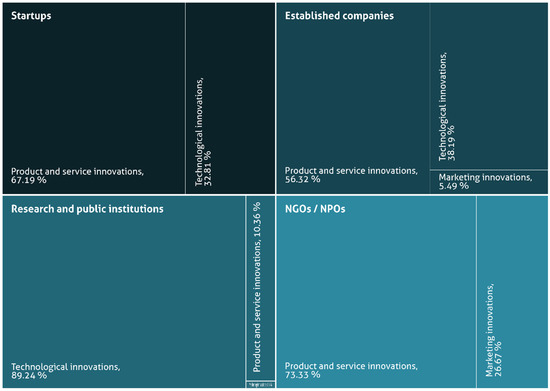

Figure 3.

Organization types and (sustainability-oriented) innovation types. Note: Chi2 = 232.27 (p = 0.000), Cramer’s V (0.391, p = 0.000) and the contingency coefficient CC (0.484, p = 0.000).

4. Results

As a first step, we provide descriptive statistics of our sample showing the distribution of the values of all variables (see Table 1). This provides a brief overview of the content of our innovation data. As illustrated in Table 1, 48% of the analyzed organization types were established companies and 17% were startups, with 44% of the organization types in the sample originating from the Americas and 39% from Europe.

Table 1.

Descriptive analysis of the variables.

To answer the first research question, the relationship between the type of organization (startup, established company, research and public institution, NGO/NPO) and the resulting sustainability-oriented macro trends ((1) Agricultural Innovation, (2) Circular Economy, (3) Clean Tech, (4) Energy Harvesting, (5) Ethical Consumption, (6) Zero Waste, and (7) More than one macro trend) were analyzed using cross tables and Chi square tests.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the startups addressed all six macro trends but focused primarily on the macro trends Clean Tech (24.22%) and Ethical Consumption (18.75%). In addition, over a quarter (25.78%) of all the startups addressed not just one but several macro trends. The established companies also concentrated on all six macro trends, with the macro trend Clean Tech (29.67%) being the most common one. Furthermore, almost 30% of all companies focused on more than one macro trend. Research and public institutions also addressed all six macro trends, with Clean Tech (43.03%) dominating.

Almost 18% (17.93%) of all the research and public institutions followed not just one but several macro trends. The NGOs/NPOs concentrated on only five macro trends, as the macro trend Energy Harvesting was not addressed. Accounting for a 55.33% proportion, the macro trend Ethical Consumption was the strong focus of such organizations. In addition, NGOs/NPOs only addressed one specific macro trend at a time and not several at once, as did other types of organizations.

To answer the second research question, the relationship between the type of organization (startup, established company, research and public institution, and NGO/NPO) and the resulting (sustainability-oriented) innovation types (technological innovations, marketing innovations, and product and service innovations) were analyzed using cross tables and Chi square tests.

As illustrated in Figure 3, 32.81% of the startups focused on technological innovations, whereas the majority (67.19%) focused on product and service innovations. The established companies paid attention to all three types of innovations, with a major focus on product and service innovations (56.32%). Research and public institutions focused mainly on technological innovations (89.24%), while NGOs/NPOs only focused on product and service innovations (73.33%) and on marketing innovations (26.67%).

Although we analyzed for differences concerning the regions ((1) Africa, (2) Americas, (3) Asia, (4) Europe or (5) Oceania) and ages of the organization types and their specific innovation type foci, no significant differences were found in the data.

5. Discussion

The present study analyzes whether different types of organizations focus on different sustainability-oriented macro trends (RQ1) and different types of sustainability-oriented innovations (RQ2). Overall, the results indicate that depending on the type of organization, different sustainability-oriented macro trends and different types of sustainability-oriented innovations can be identified.

5.1. All Organization Types Address Each Sustainability-Oriented Macro Trend in a Specific Way

With regard to research question 1, the results show that almost all types of organizations focus on almost all macro trends. This means that almost every organization type addressed each macro trend in a specific way, as enumerated in the following subsections.

5.1.1. Macro Trend: Agricultural Innovations

Startups (17.19%) were the organizations with the largest share of Agricultural Innovations. This may be explained by their ability to adapt faster to changing consumer preferences [67], especially in the food sector [68,69,70]. This may give rise to innovations such as innovative (organic) pest control systems, genetic adaptations of plants, and high-tech solutions such as farm robotics [70], vertical farming methods [20], or field robotics [71]. These new innovative methods and processes in the agricultural and food sector may primarily be tackled and driven forward by startups in the first place.

Besides startups, 13.33% of NGOs/NPOs focused on innovations in this domain, as NGOs/NPOs play an important role as networking entities within an agricultural innovation system [72]. The research needs and the development potential of technologies in the macro trend Agricultural Innovation [73] explain some of the activities of public research institutions (13.15%) in this field.

5.1.2. Macro Trend: Circular Economy

The macro trend Circular Economy played a central role in the innovations of NGOs/NPOs (20.00%). This might be due to the fact that NGOs are key players in the dissemination of and transition toward a more Circular Economy in society [24]. NGOs contribute to this macro trend by “concept formation, vision creation, and formulation of strategies” [74] (p. 194) and by starting projects that push forward the aims of a Circular Economy [74]. The relatively low percentages found within the other types of organizations can possibly be explained by the fact that the Circular Economy “worldwide is still at an early stage of development” [24] (p. 27).

A Circular Economy must be accompanied by a transformation of the social structures of consumption and production systems [24,25]. Therefore, it is associated with rather exorbitant costs, making it less attractive for both established companies (8.24%) and startups (7.81%) alike. Nevertheless, size and age might also have opposing effects on the attractiveness of the Circular Economy for established and startup companies by creating new business model opportunities, innovations, and, consequently, a competitive advantage [25,74,75,76,77].

As demonstrated by the results, 7.57% of innovations originating from research and public institutions focused on the Circular Economy macro trend. This share can be explained by the fact that the number of published papers in research on Circular Economy has increased significantly in recent years, and the topic is becoming increasingly well known in academia [78]. In addition, this macro trend has also gained more importance in public and policy domains [23]. For instance, Germany was the first country to legislate the Circular Economy concept back in 1996 with the "Closed Substance Cycle and Waste Management Act" [79] (p. 215). Furthermore, the Circular Economy is also reflected in the “EU’s 2015 Circular Economy Strategy” [79,80], which underscores the importance of this macro trend on both governmental and research levels.

5.1.3. Macro Trend: Clean Tech

Clean Tech ranked high in the portfolio of innovations of research and public institutions (43.03%), established companies (29.67%), and startups (24.22%). This result is most certainly driven by the increasing interest in and awareness of policies and the associated research funding to fight climate change or environmental degradation [81,82,83].

The changed stakeholder expectations and policy pressures have also led established companies and startups to focus on the macro trend Clean Tech, which is fostered by shifts in investment [28,83] and collaboration patterns between them [83,84,85] to tackle the uncertainties and risks involved [85] and avoid future costs such as carbon taxation [85,86].

5.1.4. Macro Trend: Energy Harvesting

Energy Harvesting can be associated with 12.35% of the innovations originating in research and public organizations, where research and development in Energy Harvesting are recently gaining more attention as new and alternative ways “to provide a continuous power supply for small low-power devices in applications such as wireless sensing, data transmission, actuation, and medical implants” [33] (p. 1). The implementation of these technologies is still hampered by “low output performance and narrow bandwidth” [33] (p. 29) which, in turn, are addressed by continuing research and development activities. Aside from economic benefits such as saving costs [33], Energy Harvesting also has ecological benefits by allowing changes to batteries to be minimal or even unnecessary [32].

5.1.5. Macro Trend: Ethical Consumption

More than half of the innovations from NGOs/NPOs (53.33%) addressed the macro trend Ethical Consumption, which highlights the specific purpose of NGOs/NPOs: they are actors that foster sustainable or ethical consumption by increasing the awareness of the strong influence and central role that ethical consumption plays in the implementation of sustainable development [87].

Up to 20.60% of innovations from the established companies focused on Ethical Consumption. This may be explained by the increasing interest and demand of customers for sustainable and ethically responsible products and services, even in the mass market sector [88,89]. Therefore, established companies respond to customers’ needs for responsible consumption with operational and strategic changes toward more responsible production [88,90] to increase the competitiveness of their offerings and avoid damaging their brand or reputation [91] or comply with regulations [89].

Meanwhile, 18.75% of the innovations from startups focused on the macro trend Ethical Consumption. The entrepreneurs’ “principle of beneficence, or actively doing good, points towards the responsibility of contributing to positive social change within the limits of … [their] … own capacities” [92] (p. 208). They strive to contribute to the solution [92] rather than being part of the sustainability problems. Some of them do so very idealistically [51] to drive and implement “social and environmental changes in society” [51] (p. 487). Furthermore, the growing awareness about ethical consumption may influence companies’ business models in integrating more “ethical management by actively promoting environmental protection and offering products and services in the fulfilment of social responsibility” [93] (p. 278).

5.1.6. Macro Trend: Zero Waste

Zero Waste was not well represented among the four organizational origins of innovation. Only NGOs slightly tended to focus more (6.67%) on the Zero Waste trend, which may be explained by the tasks of NGOs to elevate public awareness about waste, especially Zero Waste [37]. Hereby, waste should be understood as a fruitful source for recycling, upcycling, and the creation of products that can be reused [36]. Only by achieving consciousness and support within society can the aims of Zero Waste be realized [37].

5.1.7. Nearly All Organization Types Tackled More Than One Sustainability-Oriented Macro Trend at the Same Time

Furthermore, the results show that three out of the four organization types (startup, established companies, research and public institutions) were the origins of several macro trends simultaneously. As the six macro trends are concrete manifestations of the sustainability megatrend [18], they should not only be considered individually but also as a whole. For this reason, there may be some overlap between the individual trends, either thematically or in terms of objectives. In addition, the simultaneous addressing of multiple macro trends by an organization may also indicate the urgency and importance of each macro trend. Rather than committing to only one macro trend, multiple sustainability goals of the different organization types can be combined, promoted, and achieved simultaneously.

5.2. Each Organization Type Focuses Dominantly on One Sustainability-Oriented Innovation Type

With regard to research question 2, the results show that a clear type of innovation can generally be found for each type of organization, which may be explained by the respective organizational structures and aims of the different organization types.

5.2.1. Technological Innovations

Technological innovations were found in three of the four organization types (research and public institutions, established companies, startups).

Research and public institutions clearly focused on technological innovations (89.24%). This may be explained by the fact that technological innovations play a central role in realizing sustainable development [94] and “government R&D funding (support) plays a role in regulating (green) technology innovation by environmental regulation” [95] (p. 5). Two different avenues to foster technological innovations exist: governments can foster innovations through public funding to trigger a “technology push” [86] (p. 1458), or they can create incentive systems for market participants to cause “demand pull” [86] (p. 1458) innovations. This may explain the high percentage of research and public institutions focused on technological innovations. However, funded research projects may lack the agility and speed to keep pace with the already-available technology developments, particularly in the fields of energy production, agricultural technology, and transportation technology [96].

Furthermore, 38.19% of the innovations from established companies were technological innovations. One reason for this may be the integration of sustainability as a central part of their business activities and to appropriate their innovative, sustainability-oriented technologies [13] developed internally and/or in concert with innovative startups [83].

Against this backdrop, it is not surprising that one-third of the innovations from the startups (32.81%) were technological innovations, although they might be capital-intensive and not easy realized by startups [97]. The clear advantage of sustainability-oriented startups can be seen in the “more radical sustainability innovation[s]” [13] (p. 233). Yet the advantage of established companies is based on the possibility to “carry sustainable innovation into mass markets” [13] (p. 233). Besides corporate funding opportunities such as venture capital, startups frequently receive public funding to create and realize technological innovations [97]. These different kinds of funding possibilities may explain the high number of startups focusing on technological innovations.

5.2.2. Marketing Innovations

In NGOs/NPOs, 26.67% of the innovations were marketing innovations. This result can presumably be explained by the novel requirements and challenges in customer acquisition for the cause of “mobilizing public attention to social problems and needs, serving as conduits for free expression and social change” [98] (p. 136). The strong rise in digitalization and the simultaneous increase in competition for funding sources [49,57] may explain the focus of NGOs/NPOs on marketing innovations, as potential customers may have to be actively approached through creative marketing innovations [49]. Due to their global reach, it has become necessary for NGOs to use online marketing tools for their marketing purposes, as well as for exchanges with customers and other stakeholders [49].

5.2.3. Product and Service Innovations

Product and service innovations can be found in all four types of organizations and dominate in three of the four organization types (NGOs/NPOs, startups, and established companies).

Accounting for 73.33%, NGOs/NPOs have a clear focus on product and service innovations. NGOs/NPOs become more efficient and profitable organizations by transforming their business models [98]. In particular, NPOs face “two interrelated bottlenecks: lack of funds and difficulties to grow and operate at scale” [99] (p. 720). For this business model, innovations including new products and services can be seen as a way to deal with these two constraints. Accordingly, an NPO can change from a “traditional donation-based NPO” [99] (p. 720) to a “dynamic sales-driven [or market-oriented] social enterprise” [99] (p. 720) to become financially independent and accomplish scalability of its activities and realize higher impacts [98,99].

Product and service innovations being 67.19% and 56.32% of their innovations, startups and established companies concentrated heavily on this aim. They are considered key drivers for the long-term survival of firms due to the continuous changes in customer requirements or needs for more sustainable consumption opportunities [100,101]. For startups, it seems easier to ensure that sustainability aspects are reflected in their overall missions, strategic goals, and product portfolios [13]. Established companies face the problem of being “restricted by their existing assets, which reflect past investments” [51] (p. 487) and by current, less sustainable offerings, which often cause less engagement in new, more sustainability-oriented business opportunities [51].

6. Conclusions

6.1. Enriching the Innovation Strategies of Organizations toward Enhanced Sustainability

For innovation management research, our study shows which types of organizations are already tackling sustainability-oriented macro trends and innovation types and where the more narrowly defined foci are set. The results of this study can also shape the innovation management of many organizations by highlighting the key areas that different organization types focus on and by exploring their motivations or incentives in doing so. This may help organizations push their own innovations further to become more active in certain fields of sustainability-oriented innovations and to provide long-term orientation on how to increase their competitive advantage.

To deal with changing customer needs, firms can recognize the tremendous opportunities for sustainable products and services and sustainability-oriented business models [10,102]. Innovation management in all organization types should consider existing customer needs and the current business model as elements that can be influenced and changed if necessary [10]. In particular, “mainstream customers” [13] (p. 223) may be seen as an important source to foster sustainability-oriented innovations and sustainable development. The earlier customer needs are taken into account in sustainability-oriented innovations, the higher the possible sustainability potential of the innovation [10]. The analysis conducted in this study, which was undertaken by exploring the sustainability-oriented macro trends and innovation types, also identifies unutilized future opportunities for sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainable innovation. This aspect could be particularly interesting for sustainability-oriented startups because they are usually found by idealists who want to contribute profoundly to solving the environmental and social challenges that society is facing [51] by aiming to be catalysts of a true change toward more sustainable development.

As underlined by the findings in our study, most organization types focus on technological and/or product and service innovations; marketing innovations are lacking, although they are valuable in promoting the innovativeness of an organization [10]. If this oversight is caused by a lack of management knowledge and expertise, managers could be better trained in innovative marketing tools and strategies to better exploit the potential of marketing innovations [42].

Furthermore, it could be interesting and relevant for investors to see which sustainability-oriented trends and which innovation types are currently being addressed by different organization types. This may provide insights about where future opportunities to drive new sustainability-oriented business ideas and investment opportunities may be found. However, since sustainability as a megatrend involves a very long-term perspective, investors should dedicate themselves to these core trends to foster them even if exogenous shocks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, occur.

6.2. Integrating Politics to Foster Sustainability-Oriented Macro Trend Topics and Innovations in These Fields

The obtained results may also be interesting for the field of policy. In carrying out systematic change at the macro and micro levels, policies are indispensable. It is important for politics to address each of the sustainability-oriented macro trends and sustainability-oriented innovations in general (independent of the respective specific innovation type), as policy plays an important role in fostering sustainability-oriented innovations in practice [103]. This means that all sustainability-oriented macro trends on one side and the social embedding of new sustainable technological innovations or product and service innovations on a micro level (independent of the macro trend in which they arise) on the other side should be considered and promoted as important topics and mainstays for society in order to support a global social change toward enhanced sustainability.

Within the public sector in particular, politics and regulations can play an important role in fostering sustainability-oriented innovations [14]. For example, photovoltaics or wind energy technologies as technological innovations have been supported by political funding measures in such a way that they can now be regarded as competing technologies to traditional or conventional energy-generation methods [13].

In addition, financial support programs for individual sustainability-oriented macro trend topics and innovation types are also important. In this context, various policies should be promoted, for example, “a policy for technology development” [40] (p. 1985) in the sense of coordinated financial support and exchange opportunities between (public) research institutions (with a focus on sustainability-oriented technologies) and environmental policy institutions. In addition, policies should also support the emergence, implementation, and growth potential of innovative startups and companies, especially from the sustainability-oriented technology sector [82]. More sustainability-oriented technological developments can be perceived as the main drivers toward a greener and more sustainability-oriented society and economy [81]. This way, politics can foster this transformational process [81]. As the field of politics becomes more aware of “the capabilities and innovation outcomes of Clean Tech startups [as an example], it may become easier to enact policies that encourage new business ventures to focus on these assets and capabilities that enhance innovation performance” [81] (p. 903). Stimulating the creation of and offering financial support for startups from the Clean Tech area could be a good way for policies to foster more sustainability-oriented technology developments for sustainable development [85]. Such political incentives may facilitate positive changes and innovation behaviors among firms toward a more sustainable orientation [104].

Another option to support innovative startups can be through the combination or collaboration of public and private sectors, as well as combined research and funding possibilities [86]. An interplay of financial support from politics (e.g., with regard to basic research in the field of clean technologies) and financing (follow-on) from industries (VC financing) would be conducive for the further development of technological innovations, ultimately making them suitable for the mass market [28]. This is especially important against the backdrop that the cooperation or interplays of established companies and startups are needed to realize the sustainability-oriented transformation of each industry sector; it is worth noting that governments should be aware of this so as to foster them accordingly [51]. Therefore, both organization types are important to realize sustainability and “smart innovation policies should try to leverage cooperation and competition” [51] (p. 490) between established companies and startups.

6.3. Limitations

Our study has some limitations. However, some of these limitations may represent ideas for future research. First, instances of cooperation between different organization types have not been considered for investigation, although this type of formed organization might be interesting. Cooperations can comprise “single company–single NGO collaborations to large multi-stakeholder alliances” [22] (p. 475). For the design and implementation of sustainability-oriented innovations, especially with regard to “game-changing systemic innovations” [22] (p. 476), cooperations are crucial.

Second, our data source may be perceived as another limitation, as the Trendexplorer database is still a relatively unknown data source for academic research [12]. However, it is worth noting that although the database might still be in its infancy for academic purposes, it might draw interest in future studies as a new and more practical way to obtain insights into the field of trends and innovations. It could also be interesting for future research to compare innovative organization types with other organization types that do not have such a specific focus on innovativeness to evaluate whether differences pertaining to their focus on mega, macro, or micro trends may exist.

Third, the level or degree of sustainability-oriented effort that each organization type has already achieved [105], namely, the “sustainability ambition” [75] (p. 1140), was not examined in this study. It could be of further interest to differentiate these possible level differences and determine if the focus on a macro trend or innovation type may change over time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.G., B.E. and A.K.; validation, B.E. and A.K.; formal analysis, A.G.; data curation, A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.; writing—review and editing, B.E. and A.K.; visualization, A.G.; supervision, A.K.; project administration, A.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of the data. The data were extracted from a licensed commercial database called Trendone’s Trendexplorer. The data cannot be shared.

Acknowledgments

We thank Patrick Röhm for his support during the initial data preparation and coding process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Leach, M.; Rockström, J.; Raskin, P.; Scoones, I.; Stirling, A.C.; Smith, A.; Thompson, J.; Millstone, E.; Ely, A.; Arond, E.; et al. Transforming Innovation for Sustainability. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. 1987. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- McDonagh, P.; Prothero, A. Introduction to the special issue: Sustainability as Megatrend I. J. Macromarket. 2014, 34, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelstaedt, J.D.; Shultz, C.J.; Kilbourne, W.E.; Peterson, M. Sustainability as megatrend: Two schools of macromarketing thought. J. Macromarket. 2014, 34, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seebode, D.; Jeanrenaud, S.; Bessant, J. Managing innovation for sustainability. R&D Manag. 2012, 42, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trendone GmbH. Sustainability. 2020. Available online: https://www.trendexplorer.com/en/trends/sustainability/ (accessed on 24 April 2020).

- Boons, F.; Montalvo, C.; Quist, J.; Wagner, M. Sustainable innovation, business models and economic performance: An overview. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestrea, B.S.; Ţîrcă, D.M. Innovations for sustainable development: Moving toward a sustainable future. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klewitz, J.; Hansen, E.G. Sustainability-oriented innovation of SMEs: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.G.; Grosse-Dunker, F.; Reichwald, R. Sustainability innovation cube—A framework to evaluate sustainability-oriented innovations. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2009, 13, 683–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Oslo Manual—Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Innovation Data, 3rd ed.; OECD Publications: Paris, France, 2005; Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264013100-en.pdf?expires=1623324289&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=C7E57A9F864A883B7DF447CDD7466446 (accessed on 17 May 2020).

- Ebersberger, B.; Kuckertz, A. Hop to it! The impact of organization type on innovation response time to the COVID-19 crisis. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 124, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Wagner, M. Sustainable entrepreneurship and sustainability innovation: Categories and interactions. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2011, 20, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blind, K.; Quitzow, R. Nachhaltige Innovationen. In CSR und Nachhaltige Innovation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kuckertz, A.; Wagner, M. The influence of sustainability orientation on entrepreneurial intentions—Investigating the role of business experience. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, A.L. Sustainable innovation through an entrepreneurship lens. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2000, 9, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, A.; Papp, B. Of trends and trend pyramids. J. Tour. Futures 2020, 7, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendone GmbH. What Are Mega-Trends? 2020. Available online: https://support.trendexplorer.com/en/help-topic/what-are-mega-trends/ (accessed on 26 April 2020).

- Kuckertz, A.; Hinderer, S.; Röhm, P. Entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial opportunities in the food value chain. NPJ Sci. Food 2019, 3, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendone GmbH. Agriculture Innovation. 2020. Available online: https://www.trendexplorer.com/en/trends/sustainability/agriculture-innovation/ (accessed on 22 April 2020).

- Janssen, S.; van Ittersum, M.K. Assessing farm innovations and responses to policies: A review of bio-economic farm models. Agric. Syst. 2007, 94, 622–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szekely, F.; Strebel, H. Incremental, radical and game-changing: Strategic innovation for sustainability. Corp. Gov. 2013, 13, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J.; Nuur, C.; Feldmann, A.; Eshetu Birkie, S. Circular economy as an essentially contested concept. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 175, 544–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassanelli, C.; Rosa, P.; Rocca, R.; Terzi, S. Circular economy performance assessment methods: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernick, R.; Wilder, C. The Cleantech Revolution: The Next Big Growth and Investment Opportunity; Harper Collins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, D.; Henriques, I.; Sadorsky, P. “Cleantech” venture capital around the world. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2016, 44, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudevalayam, S.; Kulkarni, P. Energy harvesting sensor nodes: Survey and implications. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tut. 2011, 13, 443–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liao, Y.; Sodano, H.A. Structural effects and energy conversion efficiency of power harvesting. J. Intell. Mat. Syst. Str. 2009, 20, 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Jasim, A.; Chen, X. Energy harvesting technologies in roadway and bridge for different applications—A comprehensive review. Appl. Energy 2018, 212, 1083–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, M.-L.; Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, K.J.R. Advances in energy harvesting communications: Past, present, and future challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tut. 2016, 18, 1384–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhong, J.; Lee, C.; Lee, S.-W.; Lin, L. A comprehensive review on piezoelectric energy harvesting technology: Materials, mechanisms, and applications. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2018, 5, 041306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrigan, M.; Szmigin, I.; Wright, J. Shopping for a better world? An interpretive study of the potential for ethical consumption within the older market. J. Consum. Mark. 2004, 21, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendone GmbH. Ethical Consumption. 2020. Available online: https://www.trendexplorer.com/en/trends/sustainability/ethical-consumption/ (accessed on 22 April 2020).

- Zaman, A.U.; Lehmann, S. The zero waste index: A performance measurement tool for waste management systems in a ‘zero waste city’. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.-Y.; Ni, S.-P.; Fan, K.-S. Working towards a zero waste environment in Taiwan. Waste Manag. Res. 2010, 28, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Li, J.; Zeng, X. Minimizing the increasing solid waste through zero waste strategy. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 104, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trendone GmbH. What Are Micro-Trends? 2020. Available online: https://support.trendexplorer.com/en/help-topic/what-are-micro-trends/ (accessed on 26 April 2020).

- Huber, J. Technological environmental innovations (TEIs) in a chain-analytical and life-cycle-analytical perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1980–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y. Marketing innovation. J. Econ. Manag. Strat. 2006, 15, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, F.J.; Parra-Requena, G.; Ruiz-Ortega, M.J.; Garcia-Villaverde, P.M. From external information to marketing innovation: The mediating role of product and organizational innovation. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2018, 33, 693–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trendone GmbH. Was Sind Micro-Trends? 2020. Available online: https://support.trendexplorer.com/help-topic/was-sind-micro-trends/ (accessed on 26 April 2020).

- Toivonen, M.; Tuominen, T. Emergence of innovations in services. Serv. Ind. J. 2009, 29, 887–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witell, L.; Snyder, H.; Gustafsson, A.; Fombelle, P.; Kristensson, P. Defining service innovation: A review and synthesis. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2863–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bitner, M.J.; Ostrom, A.L.; Morgan, F.N. Service blueprinting: A practical technique for service innovation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2008, 50, 66–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mont, O.K. Clarifying the concept of product–service system. J. Clean. Prod. 2002, 10, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, D.; Diehl, J.C.; Molenaar, N. Innovation process of new ventures driven by sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.R.C.; Laureano, R.M.S.; Moro, S. Unveiling research trends for organizational reputation in the nonprofit sector. Voluntas 2020, 31, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM). How GEM Defines Entrepreneurship. 2019. Available online: https://www.gemconsortium.org/wiki/1149 (accessed on 8 November 2019).

- Hockerts, K.; Wüstenhagen, R. Greening Goliaths versus emerging Davids—Theorizing about the role of incumbents and new entrants in sustainable entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Planko, J.; Cramer, J.; Hekkert, M.P.; Chappin, M.M.H. Combining the technological innovation systems framework with the entrepreneurs’ perspective on innovation. Technol. Anal. Strateg. 2017, 29, 614–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuckertz, A.; Berger, E.S.C.; Brändle, L. Entrepreneurship and the sustainable bioeconomy transformation. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2020, 37, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, S.; Schubert, T. Cooperation with public research institutions and success in innovation: Evidence from France and Germany. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission, Europe 2020—A Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2010; Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2010:2020:FIN:EN:PDF (accessed on 13 September 2020).

- Graf, N.F.S.; Rothlauf, F. Firm-NGO collaborations—A resource-based perspective. Z. Betriebswirt. 2012, 82, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerawardena, J.; McDonald, R.E.; Mort, G.S. Sustainability of nonprofit organizations: An empirical investigation. J. World Bus. 2010, 45, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teegen, H.; Doh, J.P.; Vachani, S. The importance of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in global governance and value creation: An international business research agenda. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2004, 35, 463–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, N.; Salzmann, O.; Steger, U.; Ionescu-Somers, A. Moving business/industry towards sustainable consumption: The role of NGOs. Eur. Manag. J. 2002, 20, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defourny, J.; Grønbjerg, K.; Meijs, L.; Nyssens, M.; Yamauchi, N. Voluntas symposium: Comments on Salamon and Sokolowski’s re-conceptualization of the third sector. Voluntas 2016, 27, 1546–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stubbs, W.; Cocklin, C. Conceptualizing a “sustainability business model”. Organ. Environ. 2008, 21, 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). Standard Country or Area Codes for Statistical Use (M49 Standard). Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/ (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- Hruschka, D.J.; Schwartz, D.; John, D.C.S.; Picone-Decaro, E.; Jenkins, R.A.; Carey, J.W. Reliability in coding open-ended data: Lessons learned from HIV behavioral research. Field Methods 2004, 16, 307–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DeCuir-Gunby, J.T.; Marshall, P.L.; McCulloch, A.W. Developing and using a codebook for the analysis of interview data: An example from a professional development research project. Field Methods 2011, 23, 136–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacQueen, K.M.; McLellan, E.; Kay, K.; Milstein, B. Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. Cult. Anthropol. Methods 1998, 10, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coghlan, C.; Labrecque, J.; Ma, Y.; Dubé, L. A biological adaptability approach to innovation for small and medium enterprises (SMEs): Strategic insights from and for health-promoting agri-food innovation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J. Consumer perception and trends about health and sustainability: Trade-offs and synergies of two pivotal issues. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 3, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcese, G.; Flammini, S.; Lucchetti, M.C.; Martucci, O. Evidence and experience of open sustainability innovation practices in the food sector. Sustainability 2015, 7, 8067–8090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waltz, E. Digital farming attracts cash to agtech startups. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 397–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Veltheim, F.R.; Heise, H. The AgTech startup perspective to farmers ex ante acceptance process of autonomous field robots. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, F.; Stuiver, M.; Beers, P.J.; Kok, K. The distribution of roles and functions for upscaling and outscaling innovations in agricultural innovation systems. Agric. Syst. 2013, 115, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A. Technology: The future of agriculture. Nature 2017, 544, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalmykova, Y.; Sadagopan, M.; Rosado, L. Circular economy—From review of theories and practices to development of implementation tools. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A.; Berger, E.S.C.; Gaudig, A. Responding to the greatest challenges? Value creation in ecological startups. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 230, 1138–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mattos, C.A.; De Albuquerque, T.L.M. Enabling factors and strategies for the transition toward a circular economy (CE). Sustainability 2018, 10, 4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henry, M.; Bauwens, T.; Hekkert, M.; Kirchherr, J. A typology of circular start-ups: An analysis of 128 circular business models. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merli, R.; Preziosi, M.; Acampora, A. How do scholars approach the circular economy? A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.; Heshmati, A.; Geng, Y.; Yu, X. A review of the circular economy in China: Moving from rhetoric to implementation. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 42, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Closing the Loop—An EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015; Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/documents-register/detail?ref=COM(2015)614&lang=en (accessed on 24 October 2020).

- Jensen, F.; Lööf, H.; Stephan, A. New ventures in cleantech: Opportunities, capabilities and innovation outcomes. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2020, 29, 902–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, A.; Antonelli, P.; Dell’Anna, L.; Pozzi, C. A network analysis using metadata to investigate innovation in clean-tech—Implications for energy policy. Energy Policy 2015, 86, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, A.; Carlei, V.; Baldassari, C. Exploring networks of proximity for partner selection, firms’ collaboration and knowledge exchange. The case of clean-tech industry. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2020, 29, 1034–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röhm, P.; Merz, M.; Kuckertz, A. Identifying corporate venture capital investors—A data-cleaning procedure. Financ. Res. Lett. 2020, 32, 101092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegeman, P.D.; Sørheim, R. Why do they do it? Corporate venture capital investments in cleantech startups. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 294, 126315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doblinger, C.; Surana, K.; Anadon, L.D. Governments as partners: The role of alliances in U.S. cleantech startup Innovation. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 1458–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariztía, T.; Kleine, D.; das Graças, S.L.; Brightwell, M.; Agloni, N.; Afonso, R.; Bartholo, R. Ethical consumption in Brazil and Chile: Institutional contexts and development trajectories. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaoikonomou, E.; Valverde, M.; Ryan, G. Articulating the meanings of collective experiences of ethical consumption. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 110, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.-Z.; Chau, K.Y.; Chien, F.; Shen, H. The Impact of startups’ dual learning on their green innovation capability: The effects of business executives’ environmental awareness and environmental regulations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastiani, R.; Montagnini, F.; Dalli, D. Ethical consumption and new business models in the food industry. Evidence from the eataly case. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunk, K.H. Exploring origins of ethical company/brand perceptions—A consumer perspective of corporate ethics. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisscher, O.; Frenkel, D.; Lurie, Y.; Nijhof, A. Stretching the frontiers: Exploring the relationships between entrepreneurship and ethics. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 60, 207–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.-C.; Yoon, S.-J. Theory-based approach to factors affecting ethical consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Khan, U.; Lee, S.; Salik, M. The influence of management innovation and technological innovation on organization performance. A mediating role of sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, Y.; Xia, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, D. Environmental regulation, government R&D funding and green technology innovation: Evidence from China provincial data. Sustainability 2018, 10, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schot, J.; Geels, F.W. Strategic niche management and sustainable innovation journeys: Theory, findings, research agenda, and policy. Technol. Anal. Strateg. 2008, 20, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, B.H.; Lerner, J. The Financing of R&D and Innovation. In Handbook of the Economics of Innovation; Hall, B.H., Rosenberg, N., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 609–639. [Google Scholar]

- Eikenberry, A.M.; Kluver, J.D. The marketization of the nonprofit sector: Civil society at risk? Public Admin. Rev. 2004, 64, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reficco, E.; Layrisse, F.; Barrios, A. From donation-based NPO to social enterprise: A journey of transformation through business-model innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 720–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongsri, N.; Chang, A.K.-H. Interactions among factors influencing product innovation and innovation behaviour: Market orientation, managerial ties, and government support. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Colombelli, A.; Krafft, J.; Vivarelli, M. To be born is not enough: The key role of innovative start-ups. Small Bus. Econ. 2016, 47, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schaltegger, S.; Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Hansen, E.G. Business cases for sustainability: The role of business model innovation for corporate sustainability. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 6, 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurana, S.; Haleem, A.; Luthra, S.; Mannan, B. Evaluating critical factors to implement sustainable oriented innovation practices: An analysis of micro, small, and medium manufacturing enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 285, 125377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provasnek, A.K.; Schmid, E.; Geissler, B.; Steiner, G. Sustainable corporate entrepreneurship: Performance and strategies toward innovation. Bus. Strateg. Environ. 2017, 26, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.J.; Ebner, D. Corporate sustainability strategies: Sustainability profiles and maturity levels. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).