Linkages between Climate Change and Coastal Tourism: A Bibliometric Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. General Result

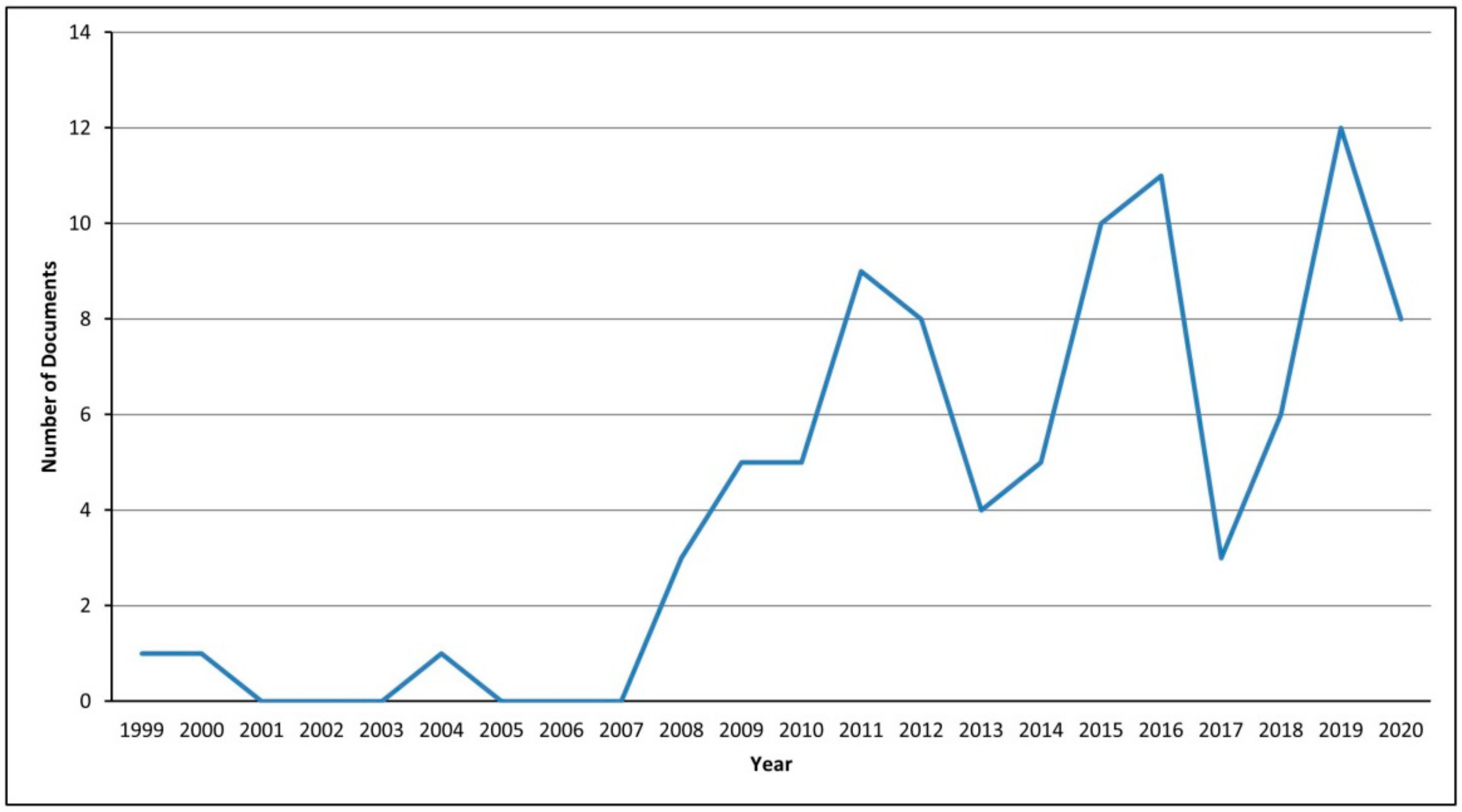

3.2. Trends and Patterns of “Climate Change and Coastal Tourism” Research in the Literature

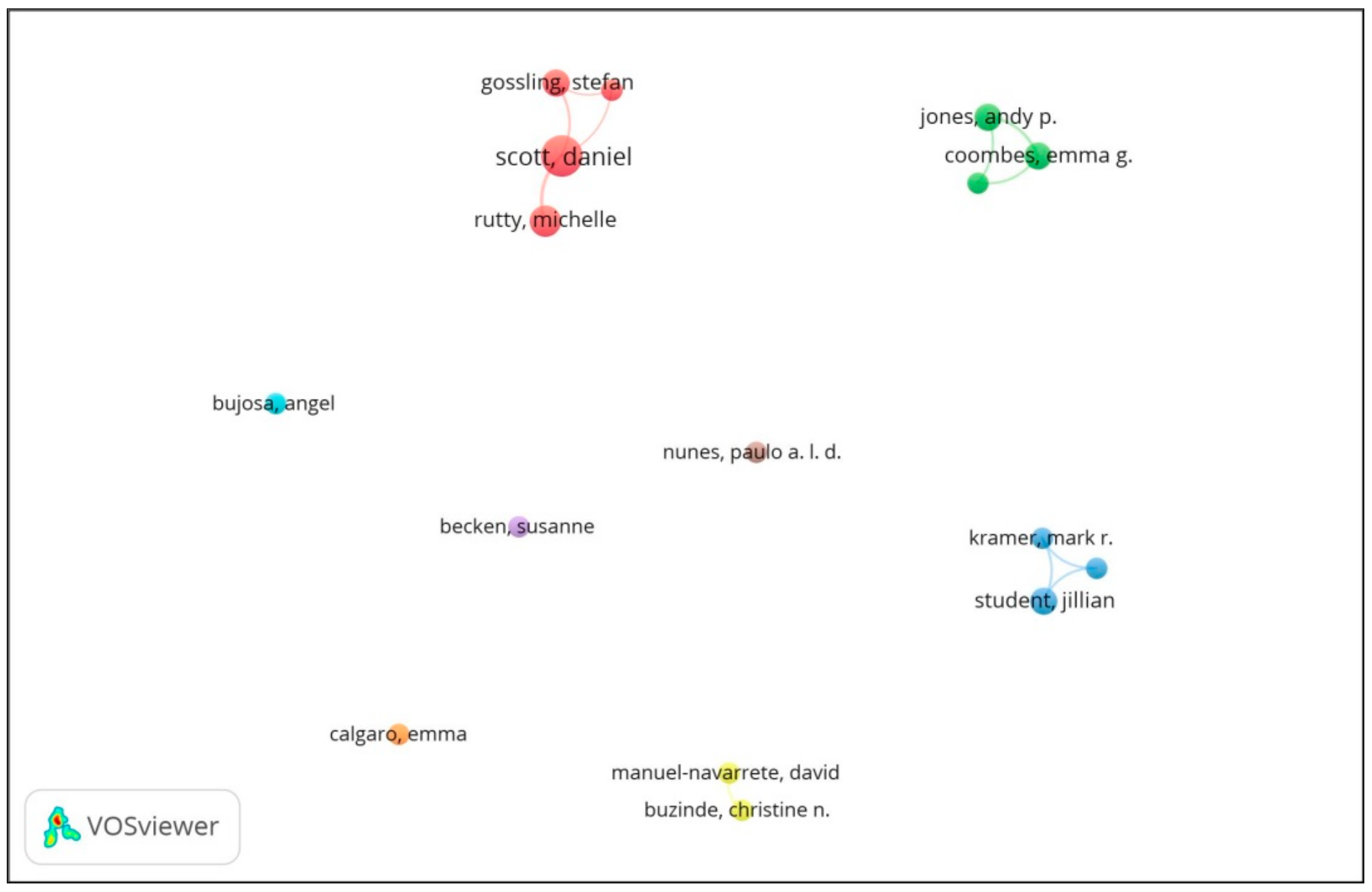

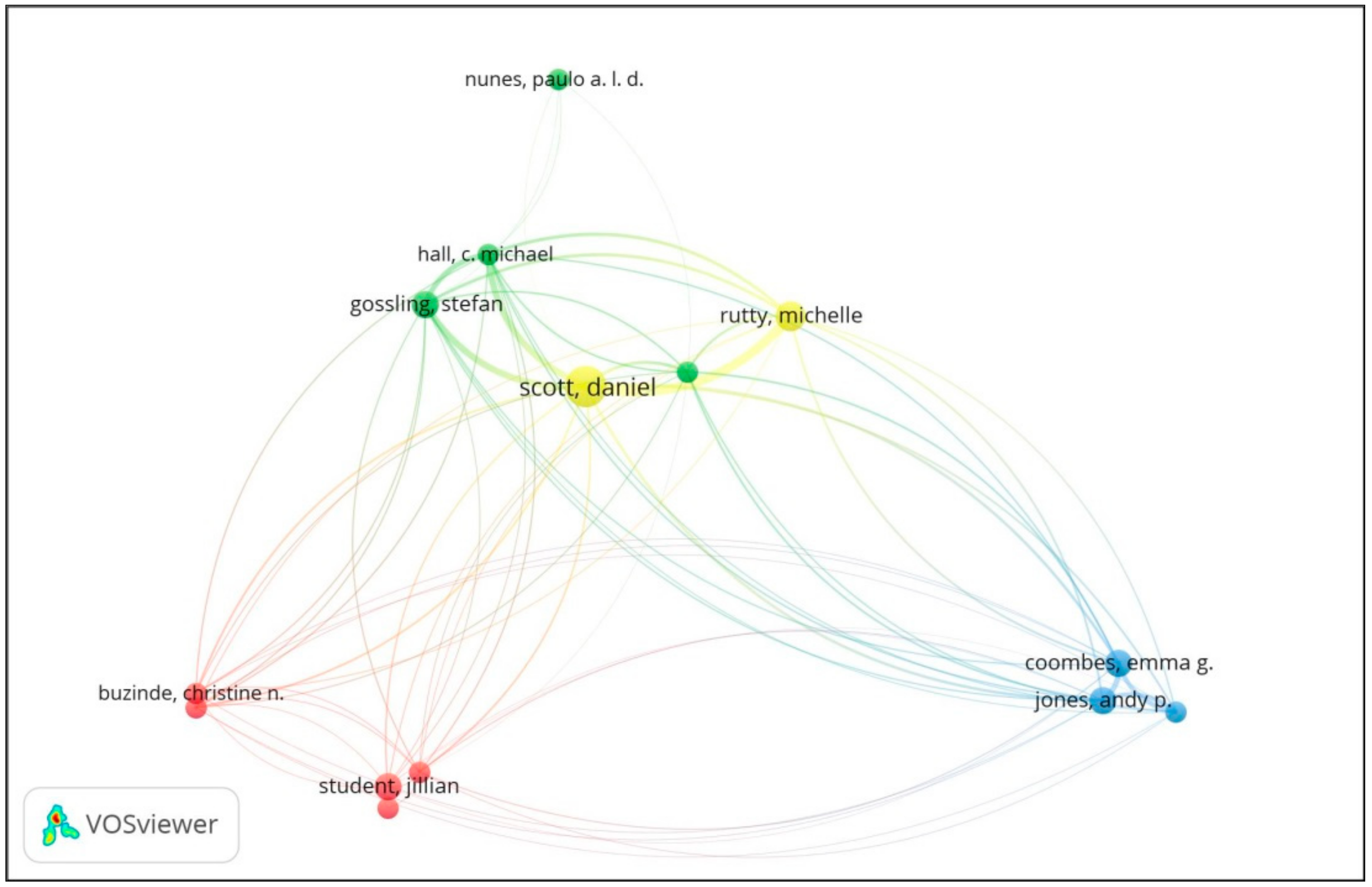

3.3. The Most Cited Paper and Influential Authors

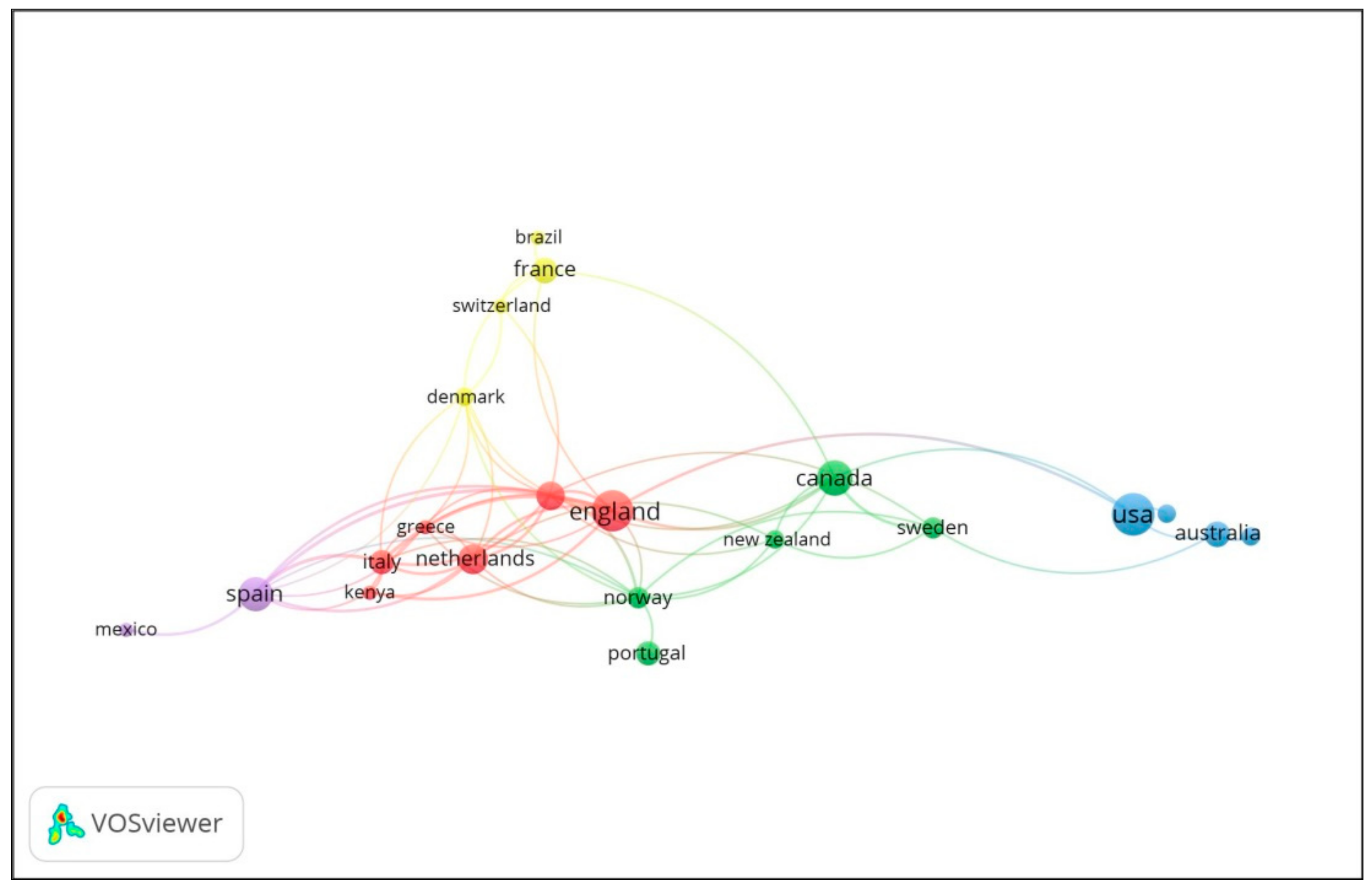

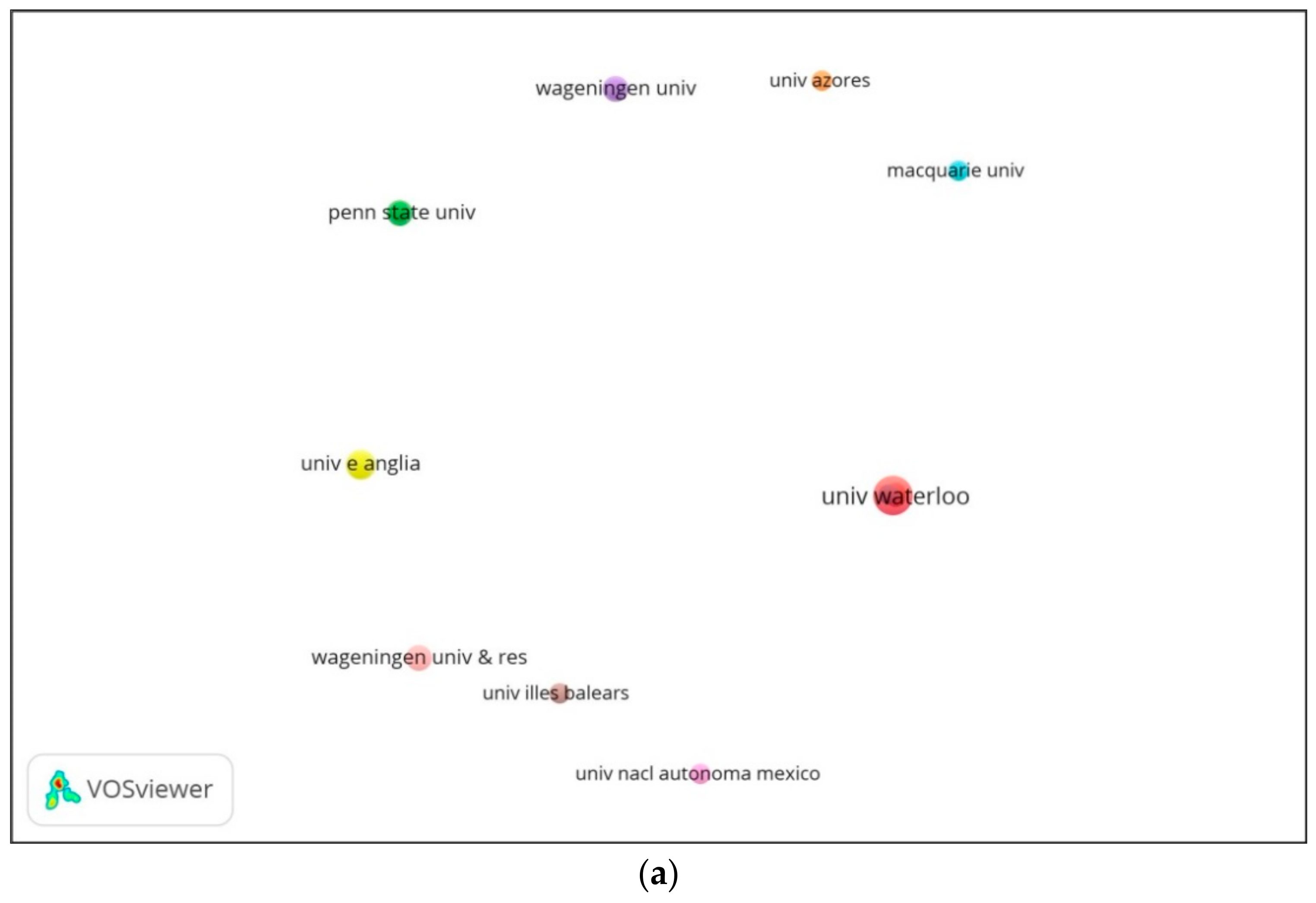

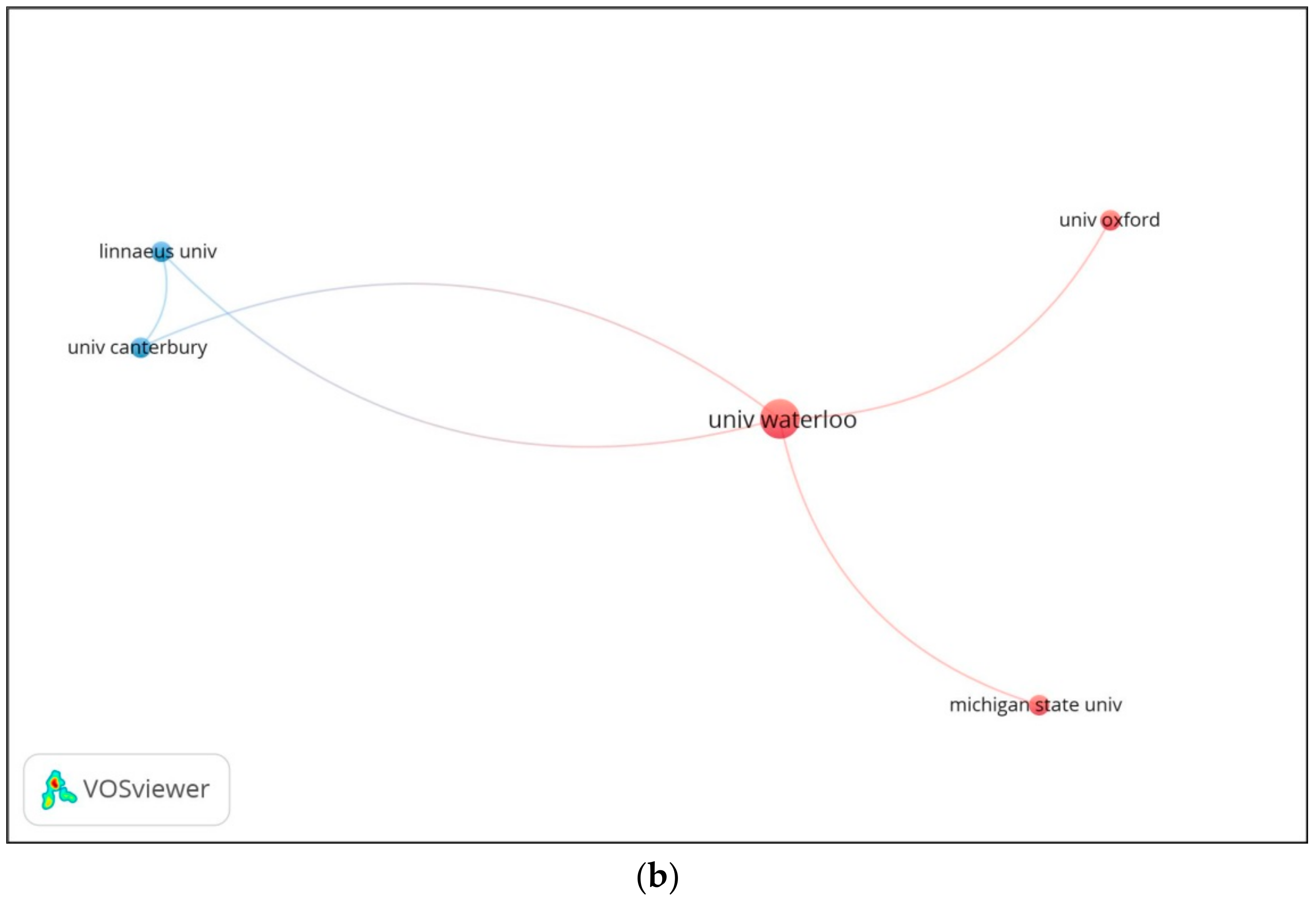

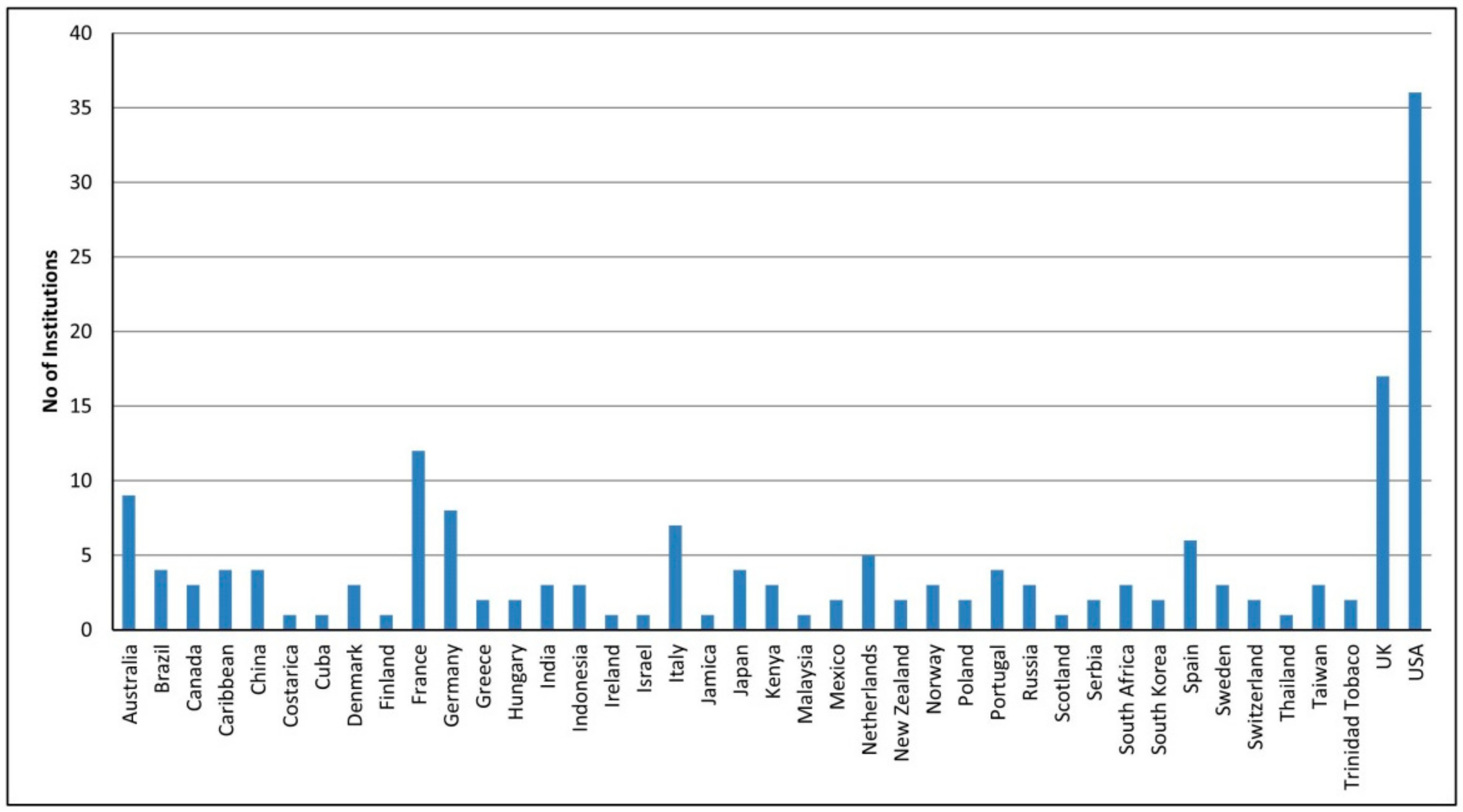

3.4. Country and Institution Co-Author Analysis

3.5. Keyword Co-Occurrence Analysis

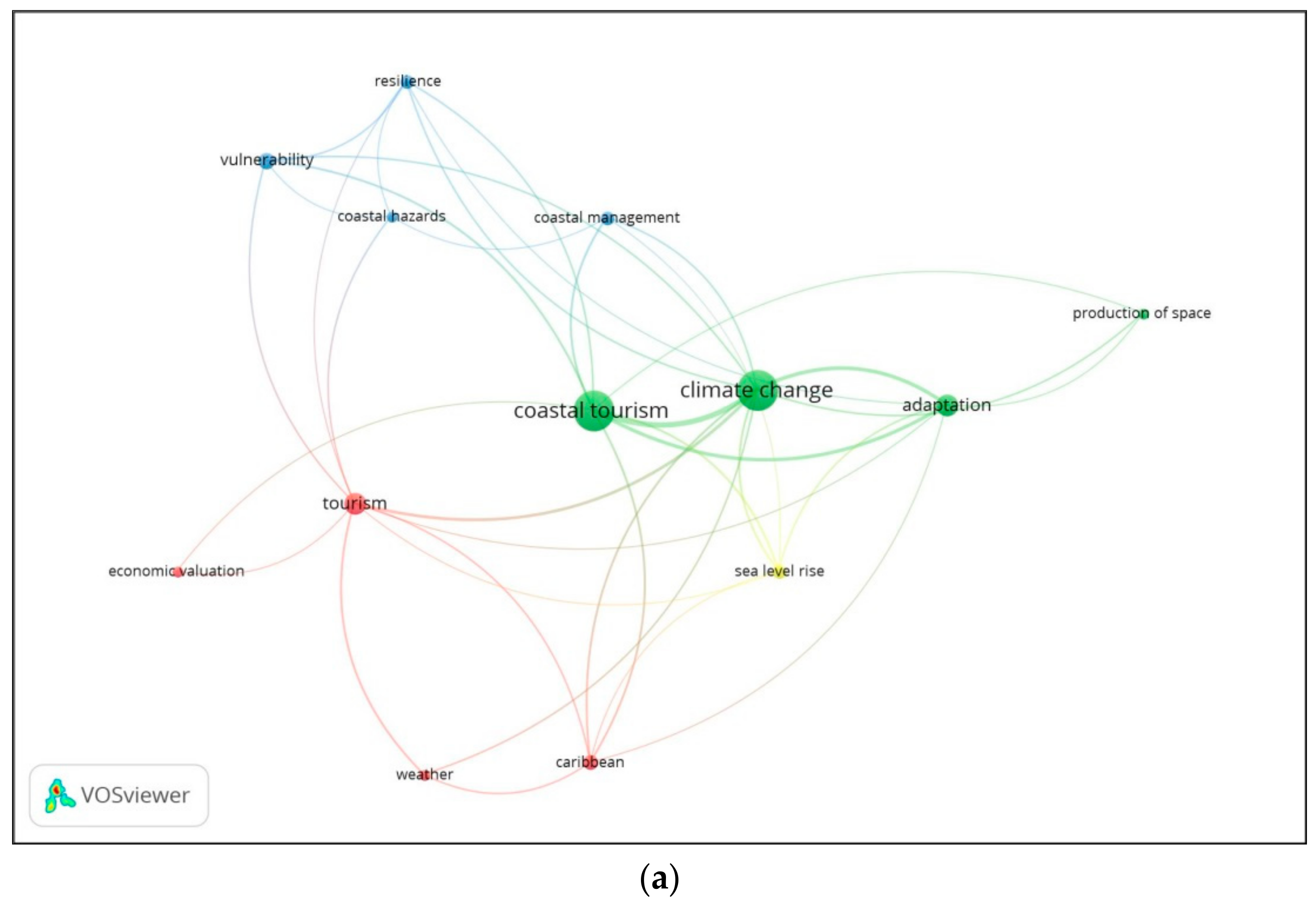

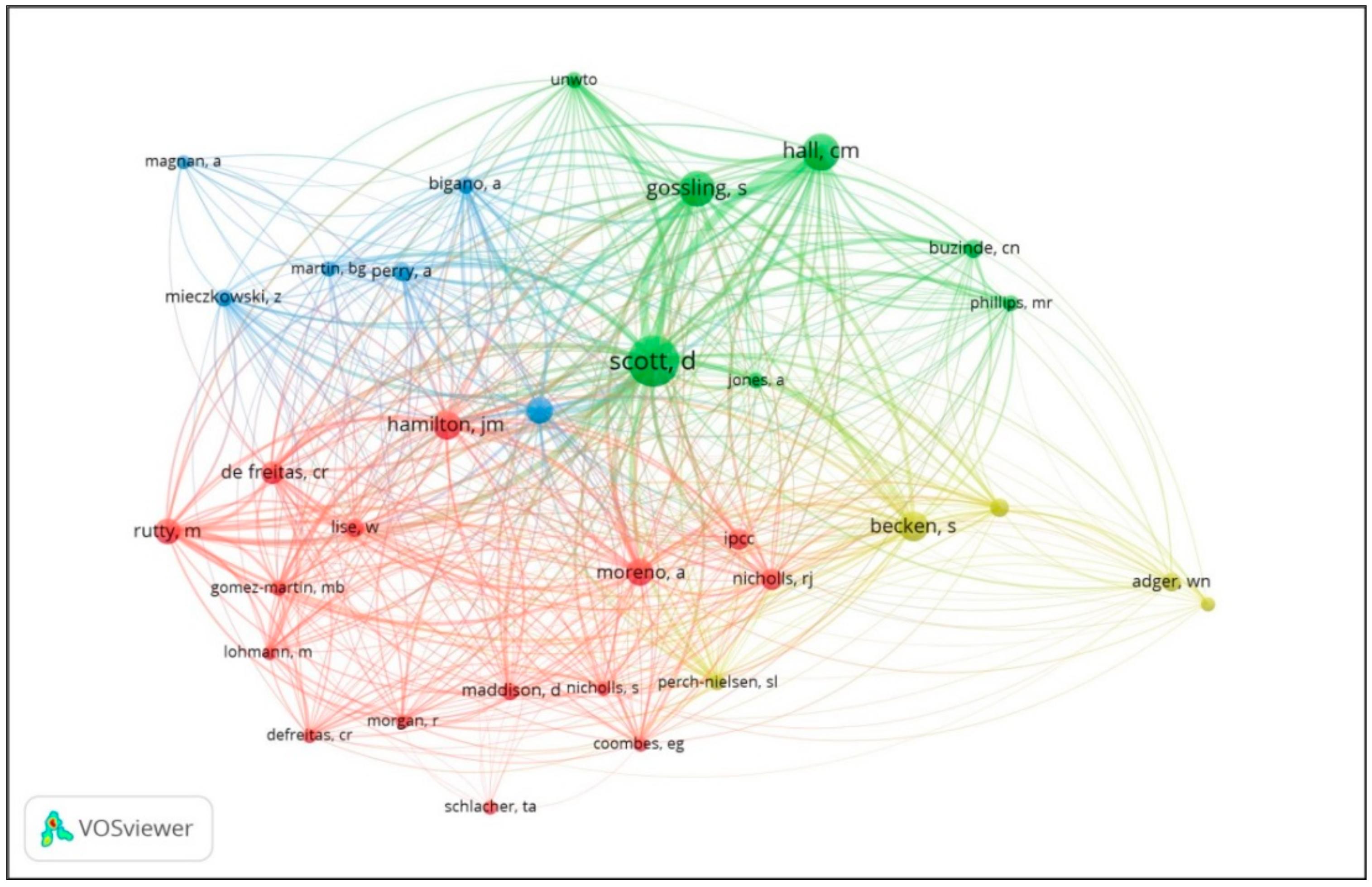

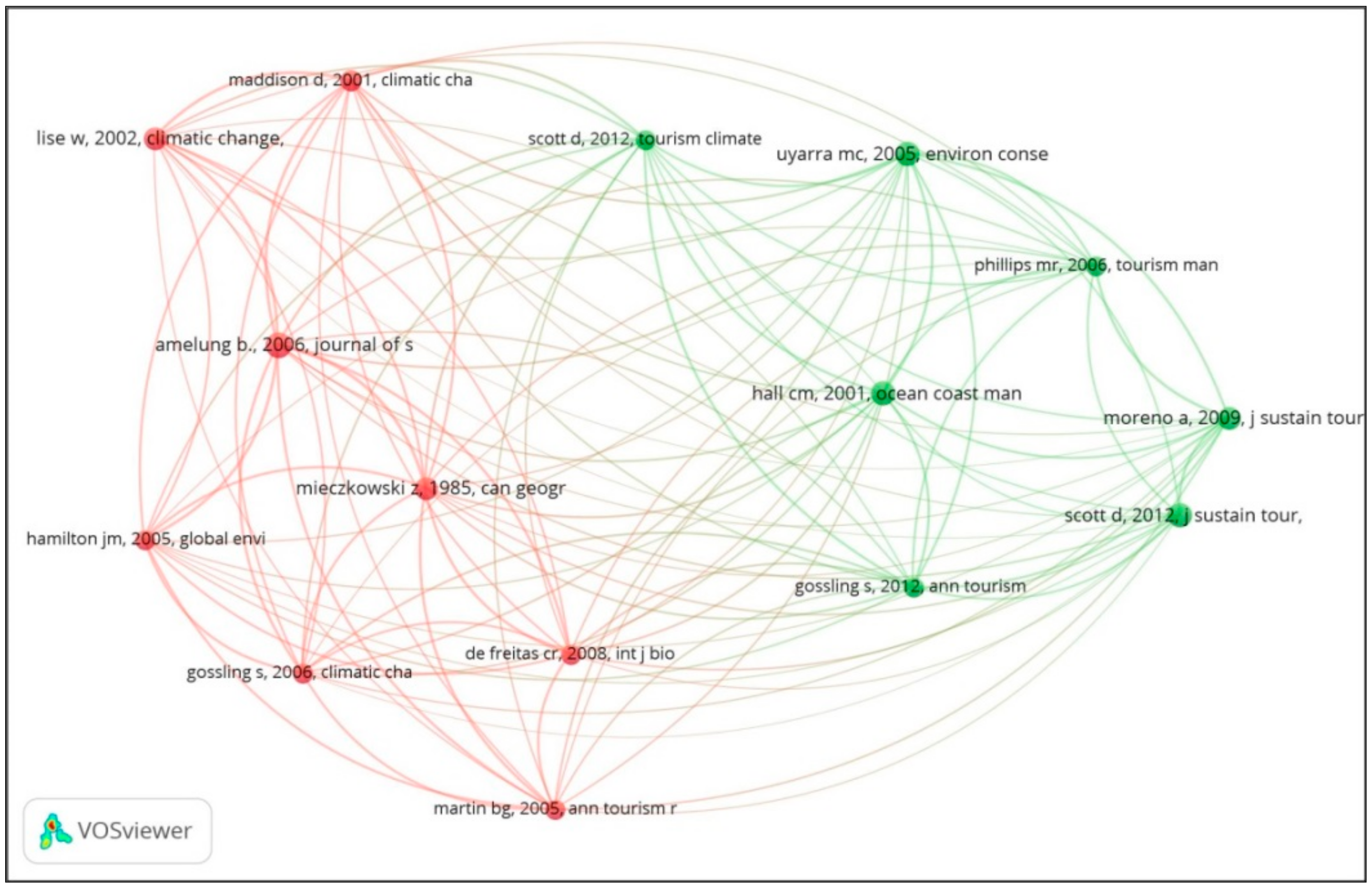

3.6. Co-Citation Analysis

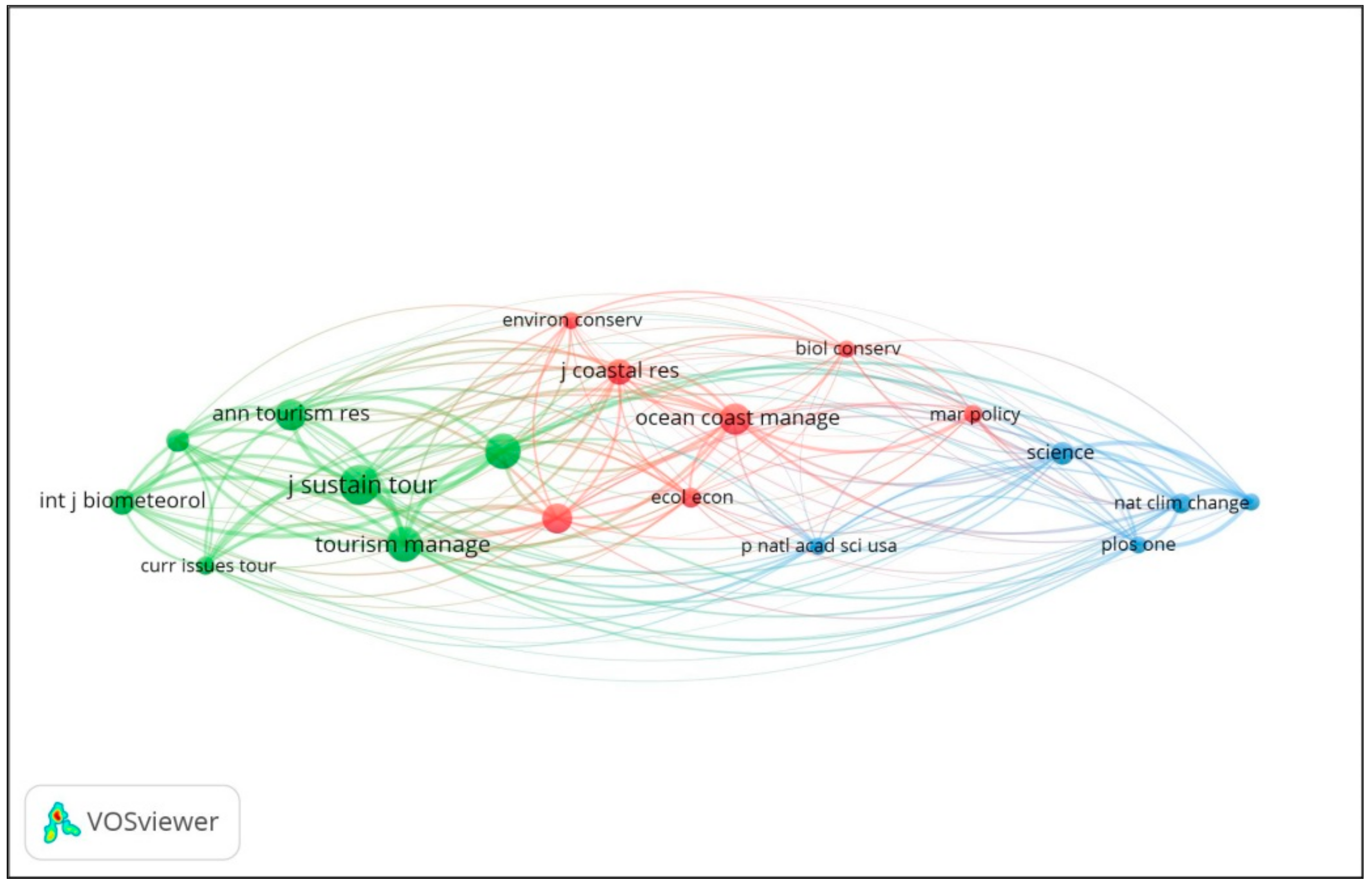

3.7. Bibliographic Coupling

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wall, G.; Harrison, R.; Kinnaird, V.; McBoyle, G.; Quinlan, C. The implications of climatic change for camping in Ontario. Recreat. Res. Rev. 1986, 13, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Amelung, B.; Moreno, A.; Scott, D. The Place of Tourism in the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report: A Review. Tour. Rev. Int. 2008, 12, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Becken, S. Adapting to climate change and climate policy: Progress, Problems and potentials. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramasamy, R.; Swamy, A. Global Warming, Climate Change and Tourism: A Review of Literature. Cult. Rev. Cult. Tur. 2012, 6, 72–98. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Thapa, B.; Yan, W. The relationship between tourism, carbon dioxide emissions, and economic growth in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UNWTO; ITF. Transport-Related CO2 Emissions of the Tourism Sector; World Tourism Organization (UNWTO): Madrid, Spain, 2019; ISBN 9789284416660. [Google Scholar]

- Lenzen, M.; Sun, Y.Y.; Faturay, F.; Ting, Y.P.; Geschke, A.; Malik, A. The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO; UNEP. Climate Change and Tourism—Responding to Global Challenges; World Tourism Organization and United Nations Environment Programme Climate: Madrid, Spain, 2008; ISBN 9789284412341. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm, I.J.; Alcântara, L.C.S.; Sampaio, C.A.C. Tourism under climate change scenarios: Impacts, possibilities, and challenges. Braz. J. Tour. 2018, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D. Sustainable tourism and the grand challenge of climate change. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, J.A.; Umar, R. Evaluation of hydrogeochemical characteristics and groundwater quality in the quaternary aquifers of Unnao District, Uttar Pradesh, India. HydroResearch 2019, 1, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karia, J.P.; Porwal, M.C.; Roy, P.S.; Sandhya, G. Forest change detection in Kalarani round, Vadodara, Gujarat—A Remote Sensing and GIS approach. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2001, 29, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damm, A.; Köberl, J.; Stegmaier, P.; Jiménez Alonso, E.; Harjanne, A. The market for climate services in the tourism sector—An analysis of Austrian stakeholders’ perceptions. Clim. Serv. 2020, 17, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Trends in ocean and coastal tourism: The end of the last frontier? Ocean Coast. Manag. 2001, 44, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umarella, M.R.; Baiquni, M.; Murti, S.H.; Marfai, M.A. Sustainability challenges in developing marine-based adventure tourism in Ambon. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitivattananon, V.; Srinonil, S. Enhancing coastal areas governance for sustainable tourism in the context of urbanization and climate change in eastern Thailand. Adv. Clim. Chang. Res. 2019, 10, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutty, M.; Scott, D. Comparison of climate preferences for domestic and international beach holidays: A case study of Canadian travelers. Atmosphere 2016, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rutty, M.; Scott, D. Bioclimatic comfort and the thermal perceptions and preferences of beach tourists. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2015, 59, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutty, M.; Scott, D. Differential climate preferences of international beach tourists. Clim. Res. 2013, 57, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutty, M.; Scott, D. Thermal range of coastal tourism resort microclimates. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 346–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabadzhyan, A.; Figini, P.; García, C.; González, M.M.; Lam-González, Y.E.; León, C.J. Climate change, coastal tourism, and impact chains–a literature review. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 2233–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyarra, M.C.; Côté, I.M.; Gill, J.A.; Tinch, R.R.T.; Viner, D.; Watkinson, A.R. Island-specific preferences of tourists for environmental features: Implications of climate change for tourism-dependent states. Environ. Conserv. 2005, 32, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lóránt, D.; Zoltán, B.; Csaba, P.; Tuohino, A. Lake Tourism and Global Climate Change: An integrative approach based on Finnish and Hungarian case-studies. Carpathian J. Earth Environ. Sci. 2012, 7, 121–136. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P.P.; Losada, I.J.; Gattuso, J.P.; Hinkel, J.; Khattabi, A.; McInnes, K.L.; Saito, Y.; Sallenger, A.; Nicholls, R.J.; Santos, F.; et al. Coastal Systems and Low-Lying Areas; Barros, V.R., Field, C.B., Dokken, D.J., Mastrandrea, M.D., Mach, K.J., Bilir, T.E., Chatterjee, M., Ebi, K.L., Estrada, Y.O., Genova, R.C., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 9781107415379. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, D.; Hall, M.; Gössling, S. Tourism and Climate Change: Impacts, Adaptation and Mitigation, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-0-203-12749-0. [Google Scholar]

- Weatherdon, L.V.; Magnan, A.K.; Rogers, A.D.; Sumaila, U.R.; Cheung, W.W.L. Observed and projected impacts of climate change on marine fisheries, aquaculture, coastal tourism, and human health: An update. Front. Mar. Sci. 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kopp, R.E.; DeConto, R.M.; Bader, D.A.; Hay, C.C.; Horton, R.M.; Kulp, S.; Oppenheimer, M.; Pollard, D.; Strauss, B.H. Evolving Understanding of Antarctic Ice-Sheet Physics and Ambiguity in Probabilistic Sea-Level Projections. Earth’s Future 2017, 5, 1217–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Le Bars, D.; Drijfhout, S.; De Vries, H. A high-end sea level rise probabilistic projection including rapid Antarctic ice sheet mass loss. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.T.; Caldeira, K. Greater future global warming inferred from Earth’s recent energy budget. Nature 2017, 552, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jevrejeva, S.; Jackson, L.P.; Grinsted, A.; Lincke, D.; Marzeion, B. Flood damage costs under the sea level rise with warming of 1.5 °C and 2 °C. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mendoza-gonz, G.; Mart, M.L.; Id, R.G.; Octavio, P.; Howard, A. Towards a Sustainable Sun, Sea, and Sand Tourism: The Value of Ocean View and Proximity to the Coast. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamilton, J.M.; Maddison, D.J.; Tol, R.S.J. Effects of climate change on international tourism. Clim. Res. 2005, 29, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gómez Martín, M.B. Weather, climate and tourism: A geographical perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 571–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelung, B.; Nicholls, S.; Viner, D. Implications of global climate change for tourism flows and seasonality. J. Travel Res. 2007, 45, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.; Becken, S. A climate change vulnerability assessment methodology for coastal tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzinde, C.N.; Manuel-Navarrete, D.; Yoo, E.E.; Morais, D. Tourists’ perceptions in a climate of change: Eroding Destinations. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 333–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Hall, M.; Gössling, S. International tourism and climate change. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2012, 3, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M.; Ceron, J.P.; Dubois, G. Consumer behaviour and demand response of tourists to climate change. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, P.; Bibbings, L. Climate change and tourism. In The Routledge Handbook of Tourism and the Environment; Holden, A., Fennell, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA,, 2013; pp. 406–420. ISBN 9780203121108. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M.; Suphachalasai, S. Assessing the Costs of Climate Change and Adaptation in South Asia; Asian Development Bank: Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2014; ISBN 9789292545109. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, D. Climate Change Implications for Tourism. In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Tourism; Lew, A.A., Hall, C.M., Williams, A.M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: West Sussex, UK, 2014; pp. 1–668. ISBN 0631235647. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling, S.; Hall, C.M.; Scott, D. Coastal and Ocean Tourism. In Handbook on Marine Environment Protection; Salomon, M., Markus, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 1–2, pp. 773–790. ISBN 9783319601540. [Google Scholar]

- Buultjens, J.; Ratnayake, I.; Gnanapala, W.K.A. Case Study Sri Lanka: Climate Change Challenges for the Sri Lankan Tourism Industry. In Global Climate Change and Coastal Tourism: Recognizing Problems, Managing Solutions and Future Expectations; Jones, A., Phillips, M., Eds.; CAB International: Oxfordshire, UK; Boston, MA, USA, 2018; Volume 18, pp. 200–211. ISBN 9781780648453. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, D.; Hall, M.; Gössling, S. Global tourism vulnerability to climate change. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 77, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Yin, J.; Wu, B. Climate change and tourism: A scientometric analysis using CiteSpace. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 108–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, C.O.; Bonetti, J. Bibliometric analysis of the scientific production on coastal communities’ social vulnerability to climate change and to the impact of extreme events. Nat. Hazards 2020, 102, 1589–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- José, M.; Aparecida, M.; Barreiros, E.; Souza, D. Geospatiality of climate change perceptions on coastal regions: A systematic bibliometric analysis. Geogr. Sustain. 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Marc, W. How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulet-Forteza, C.; Genovart-Balaguer, J.; Mauleon-Mendez, E.; Merigó, J.M. A bibliometric research in the tourism, leisure and hospitality fields. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 819–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulet-Forteza, C.; Martorell-Cunill, O.; Merigó, J.M.; Genovart-Balaguer, J.; Mauleon-Mendez, E. Twenty five years of the Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing: A bibliometric ranking. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 1201–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrigos-Simon, F.J.; Narangajavana-Kaosiri, Y.; Lengua-Lengua, I. Tourism and sustainability: A bibliometric and visualization analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rana, I.A. Disaster and climate change resilience: A bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 50, 101839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Reporting Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Oliveira, O.J.; Francisco, F.; Juliani, F.; César, L.; Motta, F. Bibliometric Method for Mapping the State-of-the-Art and Identifying Research Gaps and Trends in Literature: An Essential Instrument to Support the Development of Scientific Projects. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, H.; Tang, M.; Luo, L.; Li, C.; Chiclana, F.; Zeng, X. A Bibliometric Analysis and Visualization of Medical Big Data Research. Sustainability 2018, 10, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garfield, E.; Sher, I.H.; Torpie, R.J. The Use of Citation Data in Writing the History of Science; Institute for Scientific Information Inc: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Aghajani, M.A. Applying GIS to Identify the Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Road Applying GIS to Identify the Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Road Accidents Using Spatial Statistics (case study: Ilam Province, Iran) Accidents Using Spatial Statistics (case study). Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 25, 2126–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M.J.; Martínez, M.A.; Gutiérrez-salcedo, M.; Fujita, H.; Herrera-viedma, E. Knowledge-Based Systems 25 years at Knowledge-Based Systems: A bibliometric analysis. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2015, 80, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzikowski, P. A bibliometric analysis of born global firms. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 85, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalván-Burbano, N.; Pérez-Valls, M.; Plaza-Úbeda, J. innovation Analysis of scientific production on organizational innovation. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 1975, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindra, S.; Parameswar, N.; Dhir, S. Strategic management: The evolution of the field. Strateg. Chang. 2019, 28, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, S.; Ongsakul, V.; Ahmed, Z.U.; Rajan, R. Integration of knowledge and enhancing competitiveness: A case of acquisition of Zain by Bharti Airtel. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 119, 674–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Dhir, S. Structured review using TCCM and bibliometric analysis of international cause-related marketing, social marketing, and innovation of the firm. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2019, 16, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Dhir, S.; Das, V.M.; Sharma, A. Bibliometric overview of the Technological Forecasting and Social Change journal: Analysis from 1970 to 2018. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 154, 119963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, A. Statistical bibliography or bibliometrics. J. Doc. 1969, 25, 348–349. [Google Scholar]

- Merigó, J.M.; Mulet-Forteza, C.; Valencia, C.; Lew, A.A. Twenty years of Tourism Geographies: A bibliometric overview. Tour. Geogr. 2019, 21, 881–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oh, N.; Lee, J. Changing landscape of emergency management research: A systematic review with bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 49, 101658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Hu, Z.; Liu, S.; Tseng, H. Emerging trends in regenerative medicine: A scientometric analysis in CiteSpace. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2012, 12, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsanevakis, S.; Stelzenmüller, V.; South, A.; Sørensen, T.K.; Jones, P.J.S.; Kerr, S.; Badalamenti, F.; Anagnostou, C.; Breen, P.; Chust, G.; et al. Ecosystem-based marine spatial management: Review of concepts, policies, tools, and critical issues. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2011, 54, 807–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Najjar, R.G.; Walker, H.A.; Anderson, P.J.; Barren, E.J.; Bord, R.J.; Gibson, J.R.; Kennedy, V.S.; Knight, C.G.; Megonigal, J.P.; O’Connor, R.E.; et al. The potential impacts of climate change on the mid-Atlantic coastal region. Clim. Res. 2000, 14, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scott, D.; Simpson, M.C.; Sim, R. The vulnerability of Caribbean coastal tourism to scenarios of climate change related sea level rise. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 883–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kildow, J.T.; McIlgorm, A. The importance of estimating the contribution of the oceans to national economies. Mar. Policy 2010, 34, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calgaro, E.; Lloyd, K. Sun, sea, sand and tsunami: Examining disaster vulnerability in the tourism community of Khao Lak, Thailand. Singap. J. Trop. Geogr. 2008, 29, 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, R.K.; Calgaro, E.; Thomalla, F. Governing resilience building in Thailand’s tourism-dependent coastal communities: Conceptualising stakeholder agency in social-ecological systems. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombes, E.G.; Jones, A.P.; Sutherland, W.J.; Beach, W.P.; Coombes, E.G.; Jones, A.P.; Sutherland, W.J. The Implications of Climate Change on Coastal Visitor Numbers: A Regional Analysis The Implications of Climate Change on Coastal Visitor Numbers: A Regional Analysis. BioOne 2009, 25, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Student, J.; Kramer, M.R.; Steinmann, P. Annals of Tourism Research Simulating emerging coastal tourism vulnerabilities: An agent- based modelling approach. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 103034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzinde, C.N.; Manuel-navarrete, D.; Kerstetter, D.; Redclift, M. Representations and adaptation to climate change. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 581–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, W.; Qiu, J. Semantic information retrieval research based on co-occurrence analysis. Online Inf. Rev. 2014, 38, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, H. Co-citation in the scientific literature: A new measure of the relationship between two documents. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1973, 24, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelung, B.; Viner, D.; Viner, D. Mediterranean Tourism: Exploring the Future with the Tourism Climatic Index Mediterranean Tourism: Exploring the Future with the Tourism Climatic Index. J. Sustain. Tour. 2006, 14, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieczkowski, Z. The tourism climatic index: A method of evaluating world. Can. Geogr. 1985, 29, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, M.M. Bibliographic Coupling between Scientific Papers. Am. Doc. 1963, 14, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombes, E.G.; Jones, A.P.; Bateman, I.J.; Tratalos, J.A.; Gill, J.A.; Showler, D.A.; Watkinson, A.R.; Sutherland, W.J. Spatial and temporal modeling of beach use: A case study of east Anglia, UK. Coast. Manag. 2008, 37, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Article Title | Document Types | Authors | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effects of climate change on international tourism | Research article | Jacqueline M. Hamilton, David J. Maddison, Richard S. J. Tol | [32] |

| Weather, climate, and tourism | Research article | Ma Belen Gomez Martın | [33] |

| Implications of global climate change for tourism | Research article | Bas Amelung, Sarah Nicholls, David Viner | [34] |

| Climate change and tourism—responding to global challenges | Report | UNWTO, UNEP | [8] |

| Climate change vulnerability assessment | Research article | Alvaro Moreno, Susanne Becken | [35] |

| Tourists’ perceptions in a climate of change | Research article | Christine N. Buzinde, David Manuel-Navarrete, Eunice Eunjung Yoo, Duarte Morais | [36] |

| International tourism and climate change | Review article | Daniel Scott, Stefan Gossling, C. Michael Hall | [37] |

| Tourism and climate change: Impacts, Adaptation and Mitigation | Book | Daniel Scott, Stefan Gossling, C. Michael Hall | [25] |

| Consumer behaviour and demand response of tourists to climate change | Research article | Stefan Gossling, Daniel Scott, C. Michael Hall, Jean-Paul Ceron, Ghislain Dubois | [38] |

| Differential climate preferences of international beach tourists | Research article | Michelle Rutty, Daniel Scott | [19] |

| Climate change and tourism | Book chapter | Peter Burns, Lyn Bibbings | [39] |

| Assessing the Costs of Climate Change and Adaptation | Report | Mahfuz Ahmed Suphachol Suphachalasai | [40] |

| Climate Change Implications for Tourism | Book chapter | Daniel Scott | [41] |

| Coastal and Ocean Tourism | Book chapter | Stefan Gossling, C. Michael Hall, Daniel Scott, | [42] |

| Tourism under climate change scenarios | Research article | Isabel Jurema Grimm, Liliane C. S. Alcântara, Carlos Alberto Cioce Sampaio | [9] |

| Global climate change and coastal tourism | Book chapter | J. Buultjens, I. Ratnayake, W.K. Gnanapala Athula | [43] |

| Global tourism vulnerability to climate change | Research article | Daniel Scott, C. Michael Hall, Stefan Gossling, | [44] |

| The market for climate services in the tourism sector | Book chapter | Judith Köberla, Peter Stegmaierb, Elisa Jiménez Alonsoc, Atte Harjanned | [13] |

| Criteria | Quantity |

|---|---|

| Documents | 92 |

| Author | 281 |

| Source title | 59 |

| Countries | 41 |

| Institutions | 177 |

| Cited references | 1766 |

| Average citation per item | 9.2 |

| Rank | Authors | Title | Document Type | Publication Year | Total Citations | Average per Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Katsanevakis et al. [69] | Ecosystem-based marine spatial management: Review of concepts, policies, tools, and critical issues | Review article | 2011 | 220 | 22 |

| 2 | Najjar et al. [70] | The potential impacts of climate change on the mid-Atlantic coastal region | Research article | 2000 | 145 | 6.9 |

| 3 | Scott, Hall et al. [37] | International tourism and climate change | Review article | 2012 | 131 | 14.5 |

| 4 | Moreno & Becken [35] | A climate change vulnerability assessment methodology for coastal tourism | Research article | 2009 | 120 | 10 |

| 5 | Scott, Simpson et al. [71] | The vulnerability of Caribbean coastal tourism to scenarios of climate change-related sea-level rise | Research article | 2012 | 92 | 10.2 |

| 6 | Rutty & Scott [18] | Bioclimatic comfort and the thermal perceptions and preferences of beach tourists | Research article | 2015 | 67 | 11.2 |

| 7 | Kildow & McIlgorm [72] | The importance of estimating the contribution of the oceans to national economies | Research article | 2010 | 65 | 5.9 |

| 8 | Calgaro & Lloyd [73] | Sun, sea, sand and tsunami: examining disaster vulnerability in the tourism community of Khao Lak, Thailand | Research article | 2008 | 64 | 4.9 |

| 9 | Larsen et al. [74] | Governing resilience building in Thailand’s tourism-dependent coastal communities: Conceptualising stakeholder agency in social-ecological systems | Research article | 2011 | 63 | 6.3 |

| 10 | Buzinde et al. [36] | Tourists’ perceptions in a climate of change eroding destinations | Research article | 2010 | 57 | 5.2 |

| Author | No of Documents | No of Citations | Institutional Affiliation | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scott, Daniel | 7 | 362 | University of Waterloo | Canada |

| Becken, Susanne | 2 | 151 | Lincoln University | New Zealand |

| Gossling, Stefan | 3 | 144 | Linnaeus University | Sweden |

| Hall, C. Michael | 2 | 132 | University of Canterbury | New Zealand |

| Calgaro, Emma | 2 | 127 | Stockholm Environment Institute Asia | Thailand |

| Rutty, Michelle | 4 | 126 | University of Waterloo | Canada |

| Manuel-Navarrete, David | 2 | 100 | Kings College London | England |

| Buzinde, Christine N. | 2 | 100 | Pennsylvania State University | USA |

| Jones, Andy P. | 3 | 64 | University of East Anglia | England |

| Coombes, Emma G. | 3 | 64 | University of East Anglia | England |

| Keyword | No of Co-Occurrences | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|

| Climate change | 35 | 50 |

| Coastal tourism | 34 | 43 |

| Adaptation | 11 | 23 |

| Tourism | 11 | 19 |

| Vulnerability | 6 | 12 |

| Caribbean | 5 | 12 |

| Coastal management | 4 | 7 |

| Resilience | 4 | 9 |

| Sea level rise | 4 | 11 |

| Coastal hazards | 3 | 5 |

| Author | Citations | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|

| Scott, D. | 127 | 103.06 |

| Hall, C. M. | 65 | 51.3 |

| Gossling, S. | 62 | 55.28 |

| Becken, S. | 45 | 39.01 |

| Hamilton, J. M. | 42 | 39.18 |

| Moreno, A. | 37 | 34.79 |

| Amelung, B. | 36 | 34.12 |

| Rutty, M. | 28 | 24.68 |

| Nicholls, R. J. | 24 | 21.31 |

| De Freitas, C. R. | 23 | 22.25 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pathmanandakumar, V.; Chenoli, S.N.; Goh, H.C. Linkages between Climate Change and Coastal Tourism: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10830. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910830

Pathmanandakumar V, Chenoli SN, Goh HC. Linkages between Climate Change and Coastal Tourism: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability. 2021; 13(19):10830. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910830

Chicago/Turabian StylePathmanandakumar, Vyddiyaratnam, Sheeba Nettukandy Chenoli, and Hong Ching Goh. 2021. "Linkages between Climate Change and Coastal Tourism: A Bibliometric Analysis" Sustainability 13, no. 19: 10830. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910830

APA StylePathmanandakumar, V., Chenoli, S. N., & Goh, H. C. (2021). Linkages between Climate Change and Coastal Tourism: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability, 13(19), 10830. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910830