The Conflict between Preserving a ‘Sacred Natural Site’ and Exploiting Nature for Commercial Gain: Evidence from Phiphidi Waterfall in South Africa

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Understanding Sacred Natural Sites

3. Material and Methods

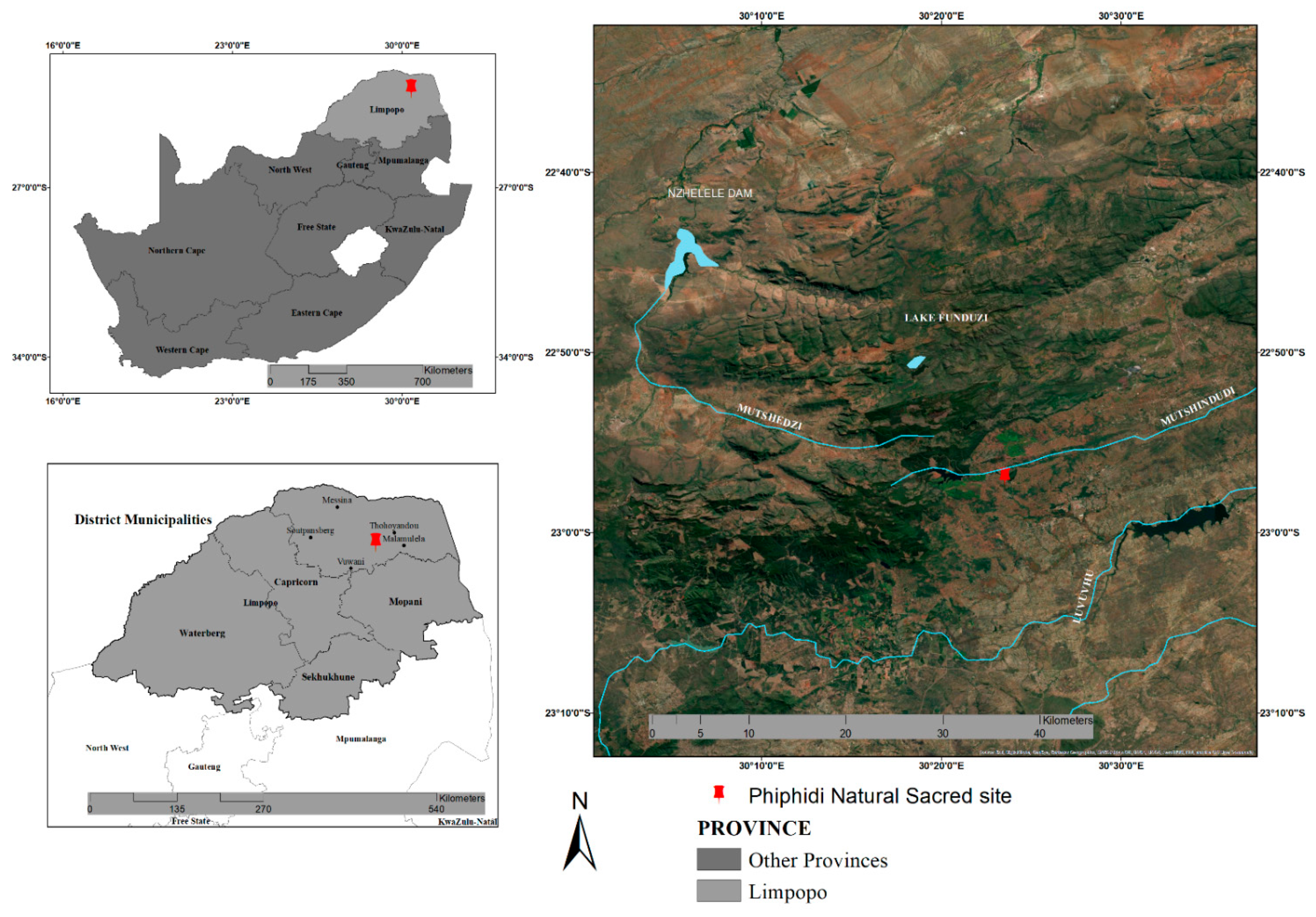

3.1. The Study Area

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Historical Use of Phiphidi Waterfall Sacred Area

4.2. Phiphidi as a Tourism Destination

‘How can you change a sacred site into a hotel? Where should Zwidudwane (water spirits), snakes, owls, monkeys and other species stay? Many trees were cut during construction; therefore, where is the rain going to come from?’(Interview, Mphatheleni Makaulula, 27 April 2021).

5. Discussion

5.1. Protection of Sacred Natural Sites

5.2. Spiritual Governance of Sacred Natural Sites

5.3. Land-Use Conflicts

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Matshidze, P.E. The Role of Makhadzi in Traditional Leadership among the Venda. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Zululand, Zululand, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fokwang, J.; Sharp, P.J. Chiefs and Democratic Transition in Africa: An Ethnographic Study in the chiefdoms of Tshivhase and Bali. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sinthumule, N.I.; Mashau, M.L. Traditional ecological knowledge and practices for forest conservation in Thathe Vondo in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, 22, e00910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odhiambo, B.D.O.; Manuga, M. Tshatshingo pothole: A sacred Vha-Venda place with cultural barriers to tourism development in South Africa. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2017, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Studley, J.; Horsley, P. Spiritual governance as an indigenous behavioural practice. In Cultural and Spiritual Significance of Nature in Protected Areas; Verschuuren, B., Brown, S., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018; pp. 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Ylhäisi, J. Traditionally Protected Forests and Sacred Forests of Zigua and Gweno Ethnic Groups in Tanzania; Department of Geography, University of Helsinki: Helsinki, Finland, 2006; ISBN 952103095X. [Google Scholar]

- Wild, R.; McLeod, C. Sacred Natural Sites: Guidelines for Protected Area Managers; IUCN Publiation Services: Gland, Switzerland, 2008; ISBN 9782831710396. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagwat, S.A.; Rutte, C. Sacred groves: Potential for biodiversity management. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2006, 4, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oviedo, G.; Jeanrenaud, S.; Otegui, M. Protecting Sacred Natural Sites of Indigenous and Traditional Peoples. IUCN 2005, 77–100. Available online: https://www.iucn.org/sites/dev/files/import/downloads/sp_protecting_sacred_natural_sites_indigenous.pdf (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Kühnert, K.; Grass, I.; Waltert, M. Sacred groves hold distinct bird assemblages within an Afrotropical savanna. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2019, 18, e00656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, A.; Asase, A.; Ekpe, P.K.; Asitoakor, B.K.; Adu-Gyamfi, A.; Avekor, P.Y. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants from Ghana; confirmation of ethnobotanical uses, and review of biological and toxicological studies on medicinal plants used in Apra Hills Sacred Grove. J. Herb. Med. 2018, 14, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roba, G.O. Anthropogenic menace on sacred natural sites: The case of Me’ee Bokko and Daraartu sacred shrines in Guji Oromo, Southern Ethiopia. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prashanth Ballullaya, U.; Reshmi, K.S.; Rajesh, T.P.; Manoj, K.; Lowman, M.; Allesh Sinu, P. Stakeholder motivation for the conservation of sacred groves in south India: An analysis of environmental perceptions of rural and urban neighbourhood communities. Land Use Policy 2019, 89, 104213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, U.K.; Bhakat, R.K. Floristic composition and biological spectrum of a sacred grove in West Midnapore district, West Bengal, India. Shengtai Xuebao Acta Ecol. Sin. 2021, 41, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helms, M.W. Sacred landscape and the early medieval European cloister: Unity, paradise, and the cosmic mountain. Anthropos 2002, 97, 435–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, N.; Higgins-Zogib, L.; Mansourian, S. The links between protected areas, faiths, and sacred natural sites. Conserv. Biol. 2009, 23, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopal, D.; von der Lippe, M.; Kowarik, I. Sacred sites as habitats of culturally important plant species in an Indian megacity. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 32, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschuuren, B.; Furuta, N. Asian Sacred Natural Sites: Philosophy and Practice in Protected Areas and Conservation; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 9781138936294. [Google Scholar]

- Studley, J. Uncovering the Intangible Values of Earth Care: Using Cognition to Reveal the Eco-Spiritual Domains and Sacred Values of the Peoples of Eastern Kham. In Sacred Natural Sites: Conserving Nature and Culture; Verschuuren, B., Wild, R., McNeely, J.A., Oviedo, G., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010; pp. 107–118. ISBN 9781849776639. [Google Scholar]

- Rutte, C. The sacred commons: Conflicts and solutions of resource management in sacred natural sites. Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 2387–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffi, L.; Woodley, E. Biocultural Diversity Conservation: A Global Sourcebook; Taylor & Francis Group: London, OH, USA, 2010; ISBN 9781849774697. [Google Scholar]

- Doffana, Z.D. Sacred natural sites, herbal medicine, medicinal plants and their conservation in Sidama, Ethiopia. Cogent Food Agric. 2017, 3, 1365399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balée, W. The research program of historical ecology. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2006, 35, 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dudley, N.; Bhagwat, S.; Higgins-Zogib, L.; Lassen, B.; Verschuuren, B.; Wild, R. Conderservation of Biodiversity in Sacred Natural Sites in Asia and Africa: A review of the scientific literature|Bas Verschuuren—Academia.edu. In Sacred Natural Sites: Conserving Nature and Culture; Verschuuren, B., Wild, R., McNeeley, J., Oviedo, G., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stara, K.; Tsiakiris, R.; Wong, J.L.G. The Trees of the Sacred Natural Sites of Zagori, NW Greece. Landsc. Res. 2015, 40, 884–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, N.B.; Lepcha, N.T.; Mahalik, S.S.; Dutta, D.; Tsanglao, B.L. Urban sacred grove forests are potential carbon stores: A case study from Sikkim Himalaya. Environ. Chall. 2021, 4, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, R. Studies on sacred groves and Taboos in Purulia district of West Bengal. Indian For. 2000, 126, 1309–1318. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagwat, S.A. Ecosystem services and sacred natural sites: Reconciling material and non-material values in nature conservation. Environ. Values 2009, 18, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avtzis, D.N.; Stara, K.; Sgardeli, V.; Betsis, A.; Diamandis, S.; Healey, J.R.; Kapsalis, E.; Kati, V.; Korakis, G.; Marini Govigli, V.; et al. Quantifying the conservation value of Sacred Natural Sites. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 222, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wadley, R.L.; Colfer, C.J.P. Sacred forest, hunting, conservation in West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Hum. Ecol. 2004, 32, 313–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagwat, S.A.; Kushalappa, C.G.; Williams, P.H.; Brown, N.D. A landscape approach to biodiversity conservation of sacred groves in the Western Ghats of India. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19, 1853–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschuuren, B.; Wild, R.; Oviedo, G.; Mcneely, J. Sacred Natural Sites: Conserving Nature and Culture; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagwat, S.; Palmer, M. Conservation: The world’s religions can help. Nature 2009, 461, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishii, H.T.; Manabe, T.; Ito, K.; Fujita, N.; Imanishi, A.; Hashimoto, D.; Iwasaki, A. Integrating ecological and cultural values toward conservation and utilization of shrine/temple forests as urban green space in Japanese cities. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2010, 6, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratiba, M.M. The Gods Will Get You—A Plea, Exploration and Assessment of Possibilities for the Rescuing of Phiphidi Waterfalls and Other Sacred Cultural Sites. Indilinga Afr. J. Indig. Knowl. Syst. 2013, 12, 142–159. [Google Scholar]

- Nekhavhambe, T.J.; van Ree, T.; Fatoki, O.S. Determination and distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in rivers, surface runoff, and sediments in and around Thohoyandou, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Water SA 2014, 40, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Munyati, C.; Sinthumule, N.I. Cover Gradients and the Forest-Community Frontier: Indigenous Forests Under Communal Management at Vondo and Xanthia, South Africa. J. Sustain. For. 2014, 33, 757–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucina, L.; Rutherford, M.C. The vegetation of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland; South African National Biodiversity Institute: Brummeria, South Africa, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Stacy, M. Phiphidi Waterfall—South Africa—Sacred Land. Available online: https://sacredland.org/phiphidi-waterfall-south-africa/ (accessed on 6 July 2021).

- Etikan, I. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andrade, C. The Inconvenient Truth About Convenience and Purposive Samples. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2021, 43, 86–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough?: An Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kansteiner, K.; König, S. The role(s) of qualitative content analysis in mixed methods research designs. Forum Qual. Soz. 2020, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, W.L. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, 7th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Harlow, UK, 2000; Volume 30, ISBN 9781292020235. [Google Scholar]

- Ramunangi Tribal Leaders, the Ramunangi Claim of Rights (Lanwadzongolo and Claim of Rights to the Sacred Sites of 2008. pp. 1–14. Available online: https://sacredland.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Ramunangi-Claim-of-Rights_15Nov08.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2021).

- Studley, J. Indigenous Sacred Natural Sites and Spiritual Governance: The Legal Case for Juristic Personhood; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Studley, J.; Bleisch, W.V. Juristic personhood for sacred natural sites: A potential means for protecting nature. Parks 2018, 24, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posey, D.A.; Plenderleith, K. Commodification of the sacred through intellectual property rights. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 83, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yablon, M. Property rights and sacred sites: Federal regulatory responses to American Indian religious claims on public land. Yale Law J. 2004, 113, 1623–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, K.A. A Property Rights Approach to Sacred Sites Cases: Asserting a Place for Indians as Nonowners. UCLA Law Rev. 2004, 52, 1061. [Google Scholar]

- Besley, T.; Ghatak, M. Property Rights and Economic Development, 1st ed.; Elsevier BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 5, ISBN 9780444529442. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrakanth, M.G.; Bhat, M.G.; Accavva, M.S. Socio-economic changes and sacred groves in South India: Protecting a community-based resource management institution. Nat. Resour. Forum 2004, 28, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, B.; Place, J. Minding the gaps: Property, geography, and Indigenous peoples in Canada. Geoforum 2013, 44, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, D.W. Property relations and economic development: The other land reform. World Dev. 1989, 17, 867–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinthumule, N.I. Resistance against conservation at the South African section of Greater Mapungubwe (trans) frontier. Afr. Spectr. 2017, 2, 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sinthumule, N.I. Land Use Change and Bordering in the Greater Mapungubwe Transfrontier Conservation Area; University of Cape Town: Cape Town, South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sinthumule, N.I. Multiple-land use practices in transfrontier conservation areas: The case of Greater Mapungubwe straddling parts of Botswana, South Africa and Zimbabwe. Bull. Geogr. 2016, 34, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ramutsindela, M.; Sinthumule, I. Property and Difference in Nature Conservation. Geogr. Rev. 2017, 107, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, C.S. The institution of taboo and the local resource management and conservation surrounding sacred natural sites in Uttarakhand, Central Himalaya. Int. J. Biodivers. Conserv. 2010, 2, 186–195. [Google Scholar]

- Ramble, C. The Navel of the Demoness: Tibetan Buddhism and Civil. Religion in Highland Nepal; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Von Der Dunk, A.; Gret-Regamey, A.; Dalang, T.; Hersperger, A.M. Defining a typology of peri-urban land-use conflits—A case study from Switzerland. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinthumule, N.I.; Ratshivhadelo, T.; Nelwamondo, T. Stakeholder perspectives on land-use conflicts in the South African section of the Greater Mapungubwe Transfrontier Conservation Area. J. Land Use Sci. 2020, 15, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Countries | Nature Rights | Juristic Personhood |

|---|---|---|

| Ecuador | √ | |

| Bolivia | √ | |

| Zealand | √ | |

| India | √ | |

| Colombia | √ |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sinthumule, N.I.; Mugwena, T.; Rabumbulu, M. The Conflict between Preserving a ‘Sacred Natural Site’ and Exploiting Nature for Commercial Gain: Evidence from Phiphidi Waterfall in South Africa. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10476. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810476

Sinthumule NI, Mugwena T, Rabumbulu M. The Conflict between Preserving a ‘Sacred Natural Site’ and Exploiting Nature for Commercial Gain: Evidence from Phiphidi Waterfall in South Africa. Sustainability. 2021; 13(18):10476. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810476

Chicago/Turabian StyleSinthumule, Ndidzulafhi Innocent, Thendo Mugwena, and Mulalo Rabumbulu. 2021. "The Conflict between Preserving a ‘Sacred Natural Site’ and Exploiting Nature for Commercial Gain: Evidence from Phiphidi Waterfall in South Africa" Sustainability 13, no. 18: 10476. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810476

APA StyleSinthumule, N. I., Mugwena, T., & Rabumbulu, M. (2021). The Conflict between Preserving a ‘Sacred Natural Site’ and Exploiting Nature for Commercial Gain: Evidence from Phiphidi Waterfall in South Africa. Sustainability, 13(18), 10476. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810476