Learning Processes and Agency in the Decarbonization Context: A Systematic Review through a Cultural Psychology Point of View

Abstract

:1. Introduction

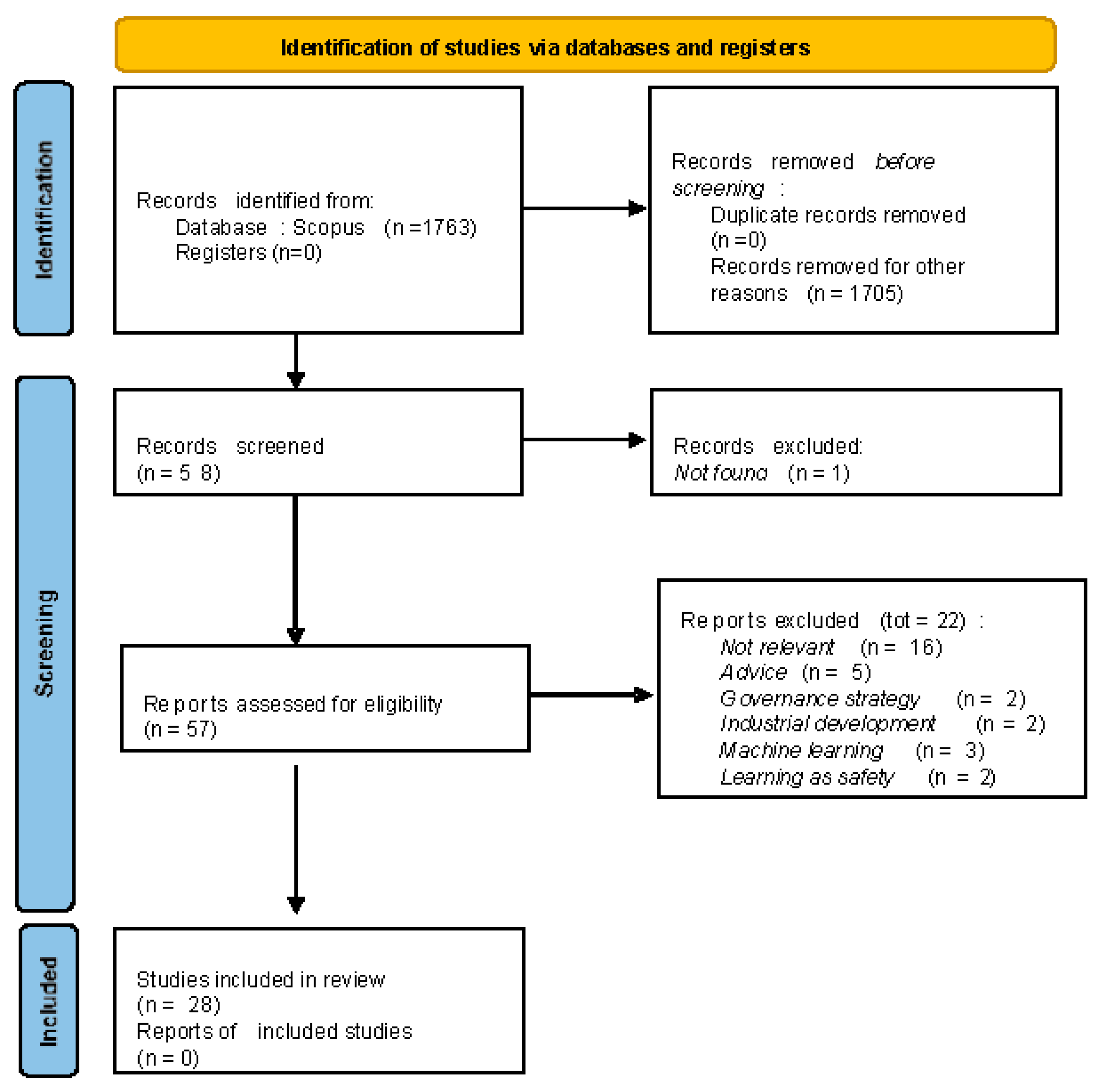

2. Materials and Methods

- How has the theoretical and methodological development of studies concerning learning evolved?

- Are dimensions compatible with a psycho-cultural approach taken into consideration?

- What kind of value is attributed to agency? Is there a risk of depoliticization?

3. Results

3.1. Research Landscape

3.2. Aggregated Response Results

3.2.1. Theory and Methodology Rationale

- What is the theoretical approach used in the article?

- 2.

- Is it conceptual or empirical research?

- 3.

- What is the definition of learning stated in the article?

- 4.

- What are the aim/scope/research questions?

- 5.

- Are there any references to transition theories?

- 6.

- Is the research conducted from an emic or etic perspective?

- 7.

- Is the object or scope of learning explicit?

3.2.2. Cultural and Material Rationale

- 8.

- Are there any cultural elements taken into account?

- 9.

- Is the learning process tied to the use of artifacts or material elements?

- 10.

- Are there any factors that drive or hinder the learning process?

- 11.

- Is the learning process explicitly related to an irrational dimension?

3.2.3. Psychosocial and Political Rationale

- 12.

- In which context are the actors taken into account?

- 13.

- Which social level is involved in learning?

- 14.

- Is the learning process referred to as a form of change?

- 15.

- Who are the actors involved?

- 16.

- Is the learning process referred to as a possibility for the emancipation of the actor involved?

- 17.

- Are there any elements that appear as power relations within the learning process?

- 18.

- Is the use of results explicitly stated?

4. Discussions

4.1. The Methodological Development of Studies on Learning

4.2. Learning Outside the Scope of Transition Theory

4.3. Considerations of the Psycho-Cultural Approach in Studies

4.4. Negative Facilitators and Positive Barriers

4.5. The Value of Agency

4.6. The Risk of Depoliticized Agency in Learning

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Authors | Title | Journal | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hoppe T., Graf A., Warbroek B., Lammers I., Lepping I. | Local governments supporting local energy initiatives: Lessons from the best practices of Saerbeck (Germany) and Lochem (The Netherlands) | Sustainability (Switzerland) | [65] |

| Lan J., Ma Y., Zhu D., Mangalagiu D., Thornton T.F. | Enabling value co-creation in the sharing economy: The case of mobike | Sustainability (Switzerland) | [81] |

| Heiskanen E., Jalas M., Rinkinen J., Tainio P | The local community as a “low-carbon lab”: Promises and perils | Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions | [66] |

| Hobson K., Mayne R., Hamilton J. | Monitoring and evaluating eco-localisation: Lessons from UK low carbon community groups | Environment and Planning A | [54] |

| Groulx M., Fishback L., Winegardner A | Citizen science and the public nature of climate action | Polar Geography | [67] |

| Kim J.E. | Fostering behaviour change to encourage low-carbon food consumption through community gardens | International Journal of Urban Sciences | [55] |

| Ollis T., Hamel-Green M. | Adult education and radical habitus in an environmental campaign: Learning in the coal seam gas protests in Australia | Australian Journal of Adult Learning | [56] |

| Upham P., Virkamäki V., Kivimaa P., Hildén M., Wadud Z. | Socio-technical transition governance and public opinion: The case of passenger transport in Finland | Journal of Transport Geography | [68] |

| Upham P., Klapper R., Carney S. | Participatory energy scenario development as dramatic scripting: A structural narrative analysis | Technological Forecasting and Social Change | [62] |

| Bratton A. | The role of talent development in environmentally sustainable hospitality: A case study of a Scottish National Health Service conference centre | Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes | [69] |

| Bruine De Bruin W., Mayer L.A., Morgan M.G. | Developing communications about CCS: Three lessons learned | Journal of Risk Research | [77] |

| Sharp D., Salter R. | Direct impacts of an urban living lab from the participants’ perspective: Livewell Yarra | Sustainability (Switzerland) | [70] |

| Heiskanen E., Hyvönen K., Laakso S., Laitila P., Matschoss K., Mikkonen I. | Adoption and use of low-carbon technologies: Lessons from 100 finnish pilot studies, field experiments and demonstrations | Sustainability (Switzerland) | [57] |

| van der Grijp N., van der Woerd F., Gaiddon B., Hummelshøj R., Larsson M., Osunmuyiwa O., Rooth R. | Demonstration projects of Nearly Zero Energy Buildings: Lessons from end-user experiences in Amsterdam, Helsingborg, and Lyon | Energy Research and Social Science | [71] |

| Alade T., Edelenbos J., Gianoli A. | Frugality in multi-actor interactions and absorptive capacity of Addis-Ababa light-rail transport | Journal of Urban Management | [72] |

| Rosenbloom D., Meadowcroft J., Sheppard S., Burch S., Williams S. | Transition experiments: Opening up low-carbon transition pathways for Canada through innovation and learning | Canadian Public Policy | [73] |

| Nikkels M.J., Guillaume J.H.A., Leith P., Mendham N.J., van Oel P.R., Hellegers P.J.G.J., Meinke H. | Participatory crossover analysis to support discussions about investments in irrigation water sources | Water (Switzerland) | [79] |

| Mychajluk L. | Learning to live and work together in an ecovillage community of practice | European Journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults | [58] |

| Hogarth J.R. | Evolutionary models of sustainable economic change in Brazil: No-till agriculture, reduced deforestation and ethanol biofuels | Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions | [78] |

| Larri L., Whitehouse H. | Nannagogy: Social movement learning for older women’s activism in the gas fields of Australia | Australian Journal of Adult Learning | [59] |

| Barazza E., Strachan N. | The co-evolution of climate policy and investments in electricity markets: Simulating agent dynamics in UK, German and Italian electricity sectors | Energy Research and Social Science | [74] |

| Pacheco L., Ningsu L., Pujol T., Gonzalez J.R., Ferrer | Impactful engineering education through sustainable energy collaborations with public and private entities | International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education | [60] |

| Nawi N.D., Phang F.A., Mohd-Yusof K., Rahman N.F.A., Zakaria Z.Y., Hassan S.A.H.B.S., Musa A.N. | Instilling low carbon awareness through technology-enhanced cooperative problem based learning | International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning | [61] |

| Kotilainen K., Aalto P., Valta J., Rautiainen A., Kojo M., Sovacool B.K | From path dependence to policy mixes for Nordic electric mobility: Lessons for accelerating future transport transitions | Policy Sciences | [75] |

| Wiegink N. | Learning lessons and curbing criticism Legitimizing involuntary resettlement and extractive projects in Mozambique: | Political Geography | [80] |

| Stoll-Kleemann S., O’Riordan | Revisiting the psychology of denial concerning low-carbon behaviors: From moral disengagement to generating social change | Sustainability (Switzerland) | [76] |

| Ollis T.A. | Adult learning and circumstantial activism in the coal seam gas protests: Informal and incidental learning in an environmental justice movement | Studies in the Education of Adults | [63] |

| Andreotta C. | Visioneering futures: A way to boost regional awareness of the low-carbon future | Regional Studies, Regional Science | [64] |

Appendix B. Results Tables

| Social Science | Education | Geography, Planning and Development | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Ranking | Country | Documents | Ranking | Country | Documents | Ranking | Country | Documents |

| 2015 | 1 | USA | 68,035 | 1 | USA | 18,008 | 1 | USA | 5716 |

| 2 | UK | 23,144 | 2 | UK | 4221 | 2 | UK | 3146 | |

| 3 | China | 12,191 | 3 | Australia | 2997 | 3 | China | 2040 | |

| 4 | Australia | 11,455 | 4 | China | 2344 | 4 | Germany | 1627 | |

| 5 | Germany | 10,538 | 5 | Canada | 2324 | 5 | Australia | 1480 | |

| 6 | Canada | 10,250 | 6 | Spain | 2051 | 6 | Canada | 1313 | |

| 7 | Spain | 9143 | 7 | Germany | 1829 | 7 | Italy | 1212 | |

| 8 | France | 8031 | 8 | Brazil | 1460 | 8 | Spain | 1141 | |

| 9 | Italy | 7011 | 9 | Turkey | 1321 | 9 | France | 1053 | |

| 10 | Netherlands | 6090 | 10 | Netherlands | 1074 | 10 | Netherlands | 982 | |

| Others | 27 | Finland | 2168 | 22 | Finland | 601 | 25 | Finland | 339 |

| 2016 | Ranking | Country | Documents | Ranking | Country | Documents | Ranking | Country | Documents |

| 1 | USA | 70,445 | 1 | USA | 18,822 | 1 | USA | 6182 | |

| 2 | UK | 24,384 | 2 | UK | 4569 | 2 | UK | 3331 | |

| 3 | China | 14,282 | 3 | Australia | 3138 | 3 | China | 3085 | |

| 4 | Australia | 11,939 | 4 | China | 2772 | 4 | Germany | 1825 | |

| 5 | Germany | 11,738 | 5 | Spain | 2422 | 5 | Australia | 1561 | |

| 6 | Canada | 10,698 | 6 | Canada | 2366 | 6 | Spain | 1447 | |

| 7 | Spain | 10,499 | 7 | Germany | 2110 | 7 | Canada | 1440 | |

| 8 | France | 8498 | 8 | Russian federation | 2047 | 8 | Italy | 1357 | |

| 9 | India | 8093 | 9 | Turkey | 1551 | 9 | France | 1095 | |

| 10 | Italy | 8032 | 10 | Brazil | 1530 | 10 | Netherlands | 1092 | |

| 2017 | Ranking | Country | Documents | Ranking | Country | Documents | Ranking | Country | Documents |

| 1 | USA | 71,056 | 1 | USA | 18,709 | 1 | USA | 6177 | |

| 2 | UK | 25,107 | 2 | UK | 4456 | 2 | China | 3907 | |

| 3 | China | 14,357 | 3 | Australia | 3271 | 3 | UK | 3415 | |

| 4 | Australia | 12,659 | 4 | China | 2612 | 4 | Germany | 1858 | |

| 5 | Germany | 12,129 | 5 | Canada | 2322 | 5 | Australia | 1790 | |

| 6 | Canada | 10,767 | 6 | Spain | 2237 | 6 | Italy | 1593 | |

| 7 | Spain | 10,714 | 7 | Germany | 1986 | 7 | Canada | 1475 | |

| 8 | Italy | 8896 | 8 | Malaysia | 1924 | 8 | Spain | 1472 | |

| 9 | France | 8431 | 9 | Indonesia | 1569 | 9 | France | 1193 | |

| 10 | India | 8058 | 10 | Brazil | 1560 | 10 | Netherlands | 1154 | |

| Other | 30 | Finland | 2168 | 22 | Finland | 601 | 25 | Finland | 339 |

| 2018 | Ranking | Country | Documents | Ranking | Country | Documents | Ranking | Country | Documents |

| 1 | USA | 74,249 | 1 | USA | 19,541 | 1 | USA | 6767 | |

| 2 | UK | 26,985 | 2 | UK | 4887 | 2 | China | 5784 | |

| 3 | China | 17,838 | 3 | Australia | 3302 | 3 | UK | 3951 | |

| 4 | Australia | 13,381 | 4 | Spain | 2985 | 4 | Germany | 2194 | |

| 5 | Germany | 12,958 | 5 | China | 2855 | 5 | Spain | 2067 | |

| 6 | Spain | 12,608 | 6 | Brazil | 2440 | 6 | Italy | 2052 | |

| 7 | Canada | 11,295 | 7 | Canada | 2403 | 7 | Australia | 1978 | |

| 8 | Italy | 9968 | 8 | Russian Federation | 2130 | 8 | Brazil | 1537 | |

| 9 | Russian Federation | 8384 | 9 | Germany | 2094 | 9 | Canada | 1473 | |

| 10 | France | 8198 | 10 | Turkey | 1698 | 10 | Netherlands | 1363 | |

| Other | 35 | Austria | 2209 | 42 | Austria | 296 | 26 | Austria | 495 |

| 2019 | Ranking | Country | Documents | Ranking | Country | Documents | Ranking | Country | Documents |

| 1 | USA | 74,668 | 1 | USA | 21,229 | 1 | USA | 6867 | |

| 2 | UK | 28,009 | 2 | UK | 5469 | 2 | China | 6291 | |

| 3 | China | 22,415 | 3 | China | 3890 | 3 | UK | 4061 | |

| 4 | Australia | 14,263 | 4 | Australia | 3666 | 4 | Spain | 2300 | |

| 5 | Germany | 13,694 | 5 | Germany | 3255 | 5 | Italy | 2244 | |

| 6 | Spain | 13,216 | 6 | Canada | 2679 | 6 | Germany | 2231 | |

| 7 | Canada | 11,874 | 7 | Indonesia | 2588 | 7 | Australia | 2135 | |

| 8 | Italy | 10,159 | 8 | Brazil | 2518 | 8 | Canada | 1640 | |

| 9 | Russian Federation | 10,076 | 9 | Germany | 2426 | 9 | Netherlands | 1411 | |

| 10 | India | 9224 | 10 | Russian Federation | 2304 | 10 | South Korea | 1340 | |

| 2020 | Ranking | Country | Documents | Ranking | Country | Documents | Ranking | Country | Documents |

| 1 | USA | 81,734 | 1 | USA | 22,331 | 1 | USA | 8298 | |

| 2 | UK | 31,974 | 2 | UK | 6215 | 2 | China | 7914 | |

| 3 | China | 26,151 | 3 | China | 4492 | 3 | UK | 5149 | |

| 4 | Spain | 16,172 | 4 | Australia | 4136 | 4 | Spain | 3530 | |

| 5 | Australia | 16,058 | 5 | Spain | 3768 | 5 | Italy | 3087 | |

| 6 | Germany | 15,388 | 6 | Canada | 3048 | 6 | Germany | 2729 | |

| 7 | Canada | 13,624 | 7 | Indonesia | 2867 | 7 | Australia | 2523 | |

| 8 | India | 11,974 | 8 | Germany | 2804 | 8 | Canada | 1998 | |

| 9 | Italy | 11,759 | 9 | Brazil | 2402 | 9 | India | 1901 | |

| 10 | Russian Federation | 10,414 | 10 | Russian Federation | 2326 | 10 | Brazil | 1871 | |

| N° | Year Of Publication | N° Article Per Year | University Affiliations Country | N° | Journal | N° | Publisher | N° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2015 | 1 | UK | 1 | Journal of Risk Research | 1 | Routledge | 1 |

| 2 | 2 | Australia | 1 | Australian Journal of Adult Learning | 1 | Adult Learning Australia Inc | 1 | |

| 3 | 3 | Finland | 1 | Journal of Transport Geography | 1 | Elsevier | 1 | |

| 4 | 4 | Finland | 2 | Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions | 1 | Elsevier | 2 | |

| 5 | 5 | Netherlands And Germany | N (1) G (1) | Sustainability | 1 | MDPI | 1 | |

| 6 | 2016 | 1 | UK | 2 | Technological Forecasting and Social Change | 1 | Elsevier | 3 |

| 7 | 2 | Germany | 2 | Environment and Planning A | 1 | Sage Publications Ltd. | 1 | |

| 8 | 2017 | 1 | Canada | 1 | European Journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults | 1 | Linkoping University Electronic Press | 1 |

| 9 | 2 | UK | 3 | Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions | 2 | Elsevier | 4 | |

| 10 | 3 | Finland | 3 | Sustainability | 2 | MDPI | 2 | |

| 11 | 4 | Australia | 2 | Sustainability | 3 | MDPI | 3 | |

| 12 | 5 | UK | 4 | International Journal of Urban Sciences | 1 | Routledge | 2 | |

| 13 | 6 | China, UK And France | 5 | Sustainability | 4 | MDPI | 4 | |

| 14 | 2018 | 1 | Austria | 1 | Regional Studies, Regional Science | 1 | Routledge | 3 |

| 15 | 2 | Canada | 2 | Canadian Public Policy | 1 | University Of Toronto Press Inc. | 1 | |

| 16 | 3 | UK | 6 | Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes | 1 | Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. | 1 | |

| 17 | 2019 | 1 | Malaysia | 1 | International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning | 1 | Kassel University Press Gmbh | 1 |

| 18 | 2 | Spain | 1 | International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education | 1 | Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. | 2 | |

| 19 | 3 | Finland | 4 | Policy Sciences | 1 | Springer | 1 | |

| 20 | 4 | Netherlands | 2 | Journal of Urban Management | 1 | Elsevier | 5 | |

| 21 | 5 | Canada | 3 | Polar Geography | 1 | Routledge | 4 | |

| 22 | 6 | Netherlands | 3 | Water (Switzerland) | 1 | MDPI | 5 | |

| 23 | 7 | Australia | 3 | Australian Journal of Adult Learning | 2 | Adult Learning Australia Inc | 2 | |

| 24 | 8 | Netherlands | 4 | Energy Research and Social Science | 1 | Elsevier | 6 | |

| 25 | 2020 | 1 | Australia | 4 | Studies in the Education of Adults | 1 | Routledge | 5 |

| 26 | 2 | Germany | 3 | Sustainability | 5 | MDPI | 6 | |

| 27 | 3 | UK | 7 | Energy Research and Social Science | 1 | Elsevier | 7 | |

| 28 | 4 | Netherlands | 5 | Political Geography | 1 | Elsevier | 8 | |

| Total | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | ||||

| ID | Question | Answer | N° (Percentage) | Articles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | What is the theoretical approach used in the article? | Theories regarding learning | 10 (36%) | [54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63] |

| Theories not directly related to learning | 13 (46%) | [64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76] | ||

| Unspecified | 5 (18%) | [77,78,79,80,81] | ||

| 2 | Is it conceptual or empirical research? | Conceptual | 4 (14%) | [73,75,78,80] |

| Empirical | 24 (86%) | [54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,74,76,77,79,81] | ||

| 3 | What is the definition of learning stated in the article? | Explicit | 12 (43%) | [55,57,58,61,63,64,65,70,71,74,75,80] |

| Implicit/mentioned/not found | 16 (57%) | [54,56,57,59,60,62,66,67,68,69,72,73,76,77,78,79,81] | ||

| 4 | What are the aim/scope/research questions? | Explicitly refers to learning | 9 (32%) | [56,57,58,59,61,63,66,71,80] |

| Implicitly refers to learning | 8 (29%) | [55,62,64,67,69,70,76,81] | ||

| Not linked with learning | 11 (39%) | [54,60,65,68,72,73,74,75,77,78,79] | ||

| 5 | Are there any references to transition theories? | No | 19 (68%) | [55,56,57,58,59,60,61,63,64,67,69,71,72,74,76,77,79,80,81] |

| Yes | 9 (32%) | [54,62,65,66,68,70,73,75,78] | ||

| 6 | Is the kind of knowledge taken into account emic or etic? | Emic | 20 (71%) | [54,55,56,57,58,59,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,70,71,72,75,76,80] |

| Etic | 8 (29%) | [60,69,73,74,77,78,79,81] | ||

| 7 | Is the object or scope of learning explicit? | No | 8 (29%) | [54,62,68,72,74,77,79,80] |

| Yes | 20 (71%) | [55,56,57,58,59,60,61,63,64,65,66,67,69,70,71,73,75,76,78,80] | ||

| 8 | Are there any cultural elements taken into account? | No | 12 (43%) | [60,62,68,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81] |

| Yes | 16 (57%) | [54,55,56,57,58,59,61,63,64,65,66,67,69,70,71,72,73] | ||

| 9 | Is the learning process tied to the use of artifacts or material elements? | No | 15 (54%) | [54,56,58,62,63,65,66,69,70,73,74,76,78,79,80] |

| Yes | 13 (46%) | [55,57,59,60,61,64,67,68,71,72,75,77,81] | ||

| 10 | Are there any factors that drive or hinder the learning process? | No | 4 (14%) | [64,68,73,78] |

| Yes | 24 (86%) | [54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,65,66,67,69,70,71,72,74,75,76,77,79,80,81] | ||

| 11 | Is the learning process explicitly related to an irrational dimension? | No | 22 (79%) | [55,56,76,77,78,79] |

| Yes | 6 (21%) | [54,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,80,81] | ||

| 12 | In which context are the actors taken into account? | Scholastic and Educational | 2 (7%) | [61,67] |

| Agricultural | 2 (7%) | [78,79] | ||

| Political | 3 (11%) | [65,75,80] | ||

| Community | 3 (11%) | [54,55,58] | ||

| Industrial and Organizational | 3 (11%) | [60,69,74] | ||

| Everyday life, household, urban, mobility | 9 (32%) | [57,62,66,68,70,71,72,73,81] | ||

| Activism | 3 (11%) | [56,59,63] | ||

| Not specified | 1 (4%) | [77] | ||

| 13 | Who are the actors involved? | Expert < - > Non-expert | 8 (29%) | [60,61,63,67,68,69,76,77] |

| Value extractor < - >Value producer | 20 (71%) | [54,55,56,57,58,59,62,64,65,66,70,71,72,73,74,75,78,79,80,81] | ||

| 14 | Is the learning process referred to as a form of change? | No | 7 (25%) | [54,57,60,62,74,77,80] |

| Yes | 21 (75%) | [55,56,58,59,61,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,75,76,78,79,81] | ||

| 15 | Which social level is involved in learning? | Intrapersonal | 9 (32%) | [55,61,63,64,67,69,76,77,79] |

| Interpersonal | 4 (14%) | [56,59,60,67] | ||

| Group/Community | 12 (43%) | [54,55,56,58,59,60,61,63,66,69,70,81] | ||

| Societal | 14 (50%) | [57,62,64,65,66,68,70,71,72,73,74,75,78,80,81] | ||

| Multiple | 10 (36%) | [55,56,59,60,61,63,64,66,67,69] | ||

| 16 | Is the learning process referred to as a possibility for emancipation of the actor involved? | No | 19 (68%) | [54,55,57,58,60,62,64,65,66,69,71,73,74,75,77,78,79,80,81] |

| Yes | 9 (32%) | [56,59,61,63,67,68,70,72,76] | ||

| 17 | Are there any elements that appear as power relations within the learning process? | No | 19 (68%) | [55,57,60,61,62,64,66,67,69,70,71,73,74,76,77,78,79,80,81] |

| Yes | 9 (32%) | [54,56,58,59,63,65,68,72,75] | ||

| 18 | Is the use of results explicitly stated? | No | 11 (39%) | [55,56,58,61,63,64,66,67,68,69,76] |

| Yes | 17 (61%) | [54,57,59,60,62,65,70,71,72,73,74,75,77,78,79,80,81] |

| Type of Learning (How?) | Actors (Who?) | Object (What?) |

|---|---|---|

| Social learning [55,65,66,68] | Community participants [54,55,58] | Decarbonization awareness [56,59]: Territorial exploitation due to renewable energy, socially elaborated during protest practice [61]: Low-carbon information gathering through digital technologies and classroom discussions [64]: Low-carbon future imagineries for the territory [69]: Elaborating and promoting a pro-environmental firm culture |

| Experiential learning [55,60,61,62,67,70,80] | Activists [56,59,63] | Niche to regime change dynamics [65]: Improvement of policy innovations for low-carbon experimentation [66]: Citizen representation of urban low-carbon experimentation [70]: Low-carbon urban development as community development [71]: Low-carbon policy for efficiency of buildings [78]: Economic development and territorial governance |

| Situated learning [54,56,57,58,63] | Policymakers [57,64,65,66,74,75,78,79,80] | New knowledge production [57]: Low-carbon technology usage [58]: Co-construction of cooperative culture [60]: Renewable energy project development [63]: Social movement practice for societal change in face of territorial exploitation [67]: Appropriation and adoption of scientific means by citizens contributing to science |

| Cognitive learning [57,76] | Students [60,61] | Cognitive and behavioral change [55]: Reducing food-related carbon footprint through pro-environmental food consumption behavior [75]: Policy improvement for urban electric vehicle mobility [76]: Overcoming moral disengagement related to high-carbon behavior [81]: Sustainable value co-creation between firm and consumers in bike-sharing projects |

| Managers and firm workers [57,69,73] | ||

| Energy users and consumers [71,72,78,81] | ||

| Citizen and non-expert stakeholders [56,62,66,67,68,70,76,77] |

References

- IPCC. 2018: Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty; Masson-Delmotte, V.P., Zhai, H.-O., Pörtner, D., Roberts, J., Skea, P.R., Shukla, A., Pirani, W., Moufouma-Okia, C., Péan, R., Pidcock, S., et al., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Loorbach, D.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Avelino, F. Sustainability Transitions Research: Transforming Science and Practice for Societal Change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2017, 42, 599–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.G.N.; Trutnevyte, E.; Strachan, N. A review of socio-technical energy transition (STET) models. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2015, 100, 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W.; Schot, J. Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 399–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, D.J.; Sovacool, B.K. Sociotechnical matters: Reviewing and integrating science and technology studies with energy social science. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 65, 101462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrell, S. Explaining sociotechnical transitions: A critical realist perspective. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 1267–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W.; Sovacool, B.K.; Schwanen, T.; Sorrell, S. The Socio-Technical Dynamics of Low-Carbon Transitions. Joule 2017, 1, 463–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geels, F.W.; Schwanen, T.; Sorrell, S.; Jenkins, K.; Sovacool, B.K. Reducing energy demand through low carbon innovation: A sociotechnical transitions perspective and thirteen research debates. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 40, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Micro-foundations of the multi-level perspective on socio-technical transitions: Developing a multi-dimensional model of agency through crossovers between social constructivism, evolutionary economics and neo-institutional theory. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 152, 119894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, O.; Nikoleris, A. Structure reconsidered: Towards new foundations of explanatory transitions theory. Res. Policy 2018, 47, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanger, L. Rethinking the Multi-level Perspective for energy transitions: From regime life-cycle to explanatory typology of transition pathways. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 71, 101829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bögel, P.M.; Upham, P. Role of psychology in sociotechnical transitions studies: Review in relation to consumption and technology acceptance. Environ. Innovat. Soc. Trans. 2018, 28, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J.; Marshall, J.P. Problems of methodology and method in climate and energy research: Socialising climate change? Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 45, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upham, P.; Bögel, P.; Dütschke, E. Thinking about individual actor-level perspectives in sociotechnical transitions: A comment on the transitions research agenda. Environ. Innovat. Soc. Trans. 2020, 34, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, M.J.; Stephens, J.C. Political power and renewable energy futures: A critical review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 35, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadowcroft, J. What about the politics? Sustainable development, transition management, and long term energy transitions. Policy Sci. 2009, 42, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feola, G. Capitalism in sustainability transitions research: Time for a critical turn? Environ. Innovat. Soc. Trans. 2020, 35, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K. What are we doing here? Analyzing fifteen years of energy scholarship and proposing a social science research agenda. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2014, 1, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royston, S.; Foulds, C. The making of energy evidence: How exclusions of Social Sciences and Humanities are reproduced (and what researchers can do about it). Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2021, 77, 102084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, P.; Flinders, M.V.; Hay, C.; Wood, M. (Eds.) Anti-Politics, Depoliticization, and Governance, 1st ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W. Socio-technical transitions to sustainability: A review of criticisms and elaborations of the Multi-Level Perspective. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2019, 39, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.; Geels, F.W.; Kern, F.; Markard, J.; Onsongo, E.; Wieczorek, A.; Alkemade, F.; Avelino, F.; Bergek, A.; Boons, F.; et al. An agenda for sustainability transitions research: State of the art and future directions. Environ. Innovat. Soc. Trans. 2019, 31, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Brisbois, M.-C. Elite power in low-carbon transitions: A critical and interdisciplinary review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 57, 101242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanger, L. Neglected systems and theorizing: A comment on the transitions research agenda. Environ. Innovat. Soc. Trans. 2020, 34, 352–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Poeck, K.; Östman, L.; Block, T. Opening up the black box of learning-by-doing in sustainability transitions. Environ. Innovat. Soc. Trans. 2020, 34, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mierlo, B.; Halbe, J.; Beers, P.J.; Scholz, G.; Vinke-de Kruijf, J. Learning about learning in sustainability transitions. Environ. Innovat. Soc. Trans. 2020, 34, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Mierlo, B.; Beers, P.J. Understanding and governing learning in sustainability transitions: A review. Environ. Innovat. Soc. Trans. 2020, 34, 255–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlak, A.K.; Heikkila, T.; Smolinski, S.L.; Huitema, D.; Armitage, D. Learning our way out of environmental policy problems: A review of the scholarship. Policy Sci. 2018, 51, 335–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, N.; Howlett, M. Who learns what in sustainability transitions? Environ. Innovat. Soc. Trans. 2020, 34, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Poeck, K.; Östman, L. Learning to find a way out of non-sustainable systems. Environ. Innovat. Soc. Trans. 2021, 39, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billi, M.; Blanco, G.; Urquiza, A. What is the ‘Social’ in Climate Change Research? A Case Study on Scientific Representations from Chile. Minerva 2019, 57, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sarrica, M.; Brondi, S.; Cottone, P.; Mazzara, B.M. One, no one, one hundred thousand energy transitions in Europe: The quest for a cultural approach. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M. Cultural Psychology: A Once and Future Discipline; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzara, B. Prospettive di Psicologia Culturale. Modelli Teorici e Contesti di Azione; Carocci: Rome, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Biddau, F.; Armenti, A.; Cottone, P. Socio-psychological aspects of grassroots participation in the Transition Movement: An Italian case study. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. 2016, 4, 142–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Cho, S.H.; Song, S. Wind, power, and the situatedness of community engagement. Public Understand. Sci. 2019, 28, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrica, M.; Biddau, F.; Brondi, S.; Cottone, P.; Mazzara, B.M. A multi-scale examination of public discourse on energy sustainability in Italy: Empirical evidence and policy implications. Energy Policy 2018, 114, 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrica, M.; Richter, M.; Thomas, S.; Graham, I.; Mazzara, B.M. Social approaches to energy transition cases in rural Italy, Indonesia and Australia: Iterative methodologies and participatory epistemologies. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 45, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upham, P.; Eberhardt, L.; Klapper, R.G. Rethinking the meaning of “landscape shocks” in energy transitions: German social representations of the Fukushima nuclear accident. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 69, 101710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarrica, M.; Brondi, S.; Piccolo, C.; Mazzara, B.M. Environmental Consciousness and Sustainable Energy Policies: Italian Parliamentary Debates in the Years 2009–2012. Society Nat. Resour. 2016, 29, 932–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontecorvo, C.; Ajello, A.M.; Zucchermaglio, C. I Contesti Sociali Dell’apprendimento; LED Edizioni Universitarie di Lettere Economia e Diritto: Milan, Italy, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, J. Situating learning in communities of practice. In Perspectives on Socially Shared Cognition; Resnick, L.B., Levine, J.M., Teasley, S.D., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1991; pp. 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning. Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bressers, J.T.; Rosenbaum, W. Innovation, learning, and environmental policy: Overcoming a plague of uncertainties. Policy Stud. J. 2000, 28, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Hahn, T.; Olsson, P.; Norberg, J. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2005, 30, 441–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Newman, M.; Gough, D. Systematic Reviews in Educational Research: Methodology, Perspectives and Application; Zawacki-Richter, O., Kerres, M., Bedenlier, S., Bond, M., Buntins, K., Eds.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Berlin, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gough, D.; Olive, S.; Thomas, J. Introducing systematic reviews. In An Introduction to Systematic Reviews, 2nd ed.; Gough, D., Olive, S., Thomas, J., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gerring, J. Social Science Methodology: A Framework; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Singleton, R.; Straits, B.R. Approaches to Social Research; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Griffiths, S. The cultural barriers to a low-carbon future: A review of six mobility and energy transitions across 28 countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 119, 109569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgerson, C. Systematic Reviews; Continuum: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Hess, D.J. Ordering theories: Typologies and conceptual frameworks for sociotechnical change. Soc. Stud. Sci. 2017, 47, 703–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, K.; Mayne, R.; Hamilton, J. Monitoring and evaluating eco-localisation: Lessons from UK low carbon community groups. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2016, 48, 1393–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, J.E. Fostering behaviour change to encourage low-carbon food consumption through community gardens. Int. J. Urban Sci. 2017, 21, 364–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollis, T.; Hamel-Green, M. Adult education and radical habitus in an environmental campaign: Learning in the coal seam gas protests in Australia. Austr. J. Adult Learn. 2015, 55, 202–219. [Google Scholar]

- Heiskanen, E.; Hyvönen, K.; Laakso, S.; Laitila, P.; Matschoss, K.; Mikkonen, I. Adoption and Use of Low-Carbon Technologies: Lessons from 100 Finnish Pilot Studies, Field Experiments and Demonstrations. Sustainability 2017, 9, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mychajluk, L. Learning to live and work together in an ecovillage community of practice. Eur. J. Res. Educ. Learn. Adults 2017, 8, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larri, L.; Whitehouse, H. Nannagogy: Social movement learning for older women’s activism in the gas fields of Australia. Austr. J. Adult Learn. 2019, 59, 27–52. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, L.; Ningsu, L.; Pujol, T.; Gonzalez, J.R.; Ferrer, I. Impactful engineering education through sustainable energy collaborations with public and private entities. Int. J. Sustain. Higher Educ. 2019, 20, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawi, N.D.; Phang, F.A.; Mohd Yusof, K.; Abdul Rahman, N.F.; Zakaria, Z.Y.; Syed Hassan, S.A.H.; Musa, A.N. Instilling Low Carbon Awareness through Technology-Enhanced Cooperative Problem Based Learning. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 2019, 14, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upham, P.; Klapper, R.; Carney, S. Participatory energy scenario development as dramatic scripting: A structural narrative analysis. Technol. Forecast. Social Chang. 2016, 103, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollis, T.A. Adult learning and circumstantial activism in the coal seam gas protests: Informal and incidental learning in an environmental justice movement. Stud. Educ. Adults 2020, 52, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreotta, C. Visioneering futures: A way to boost regional awareness of the low-carbon future. Region. Stud. Region. Sci. 2018, 5, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoppe, T.; Graf, A.; Warbroek, B.; Lammers, I.; Lepping, I. Local Governments Supporting Local Energy Initiatives: Lessons from the Best Practices of Saerbeck (Germany) and Lochem (The Netherlands). Sustainability 2015, 7, 1900–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heiskanen, E.; Jalas, M.; Rinkinen, J.; Tainio, P. The local community as a “low-carbon lab”: Promises and perils. Environ. Innovat. Soc. Trans. 2015, 14, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groulx, M.; Fishback, L.; Winegardner, A. Citizen science and the public nature of climate action. Polar Geogr. 2019, 42, 176–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upham, P.; Virkamäki, V.; Kivimaa, P.; Hildén, M.; Wadud, Z. Socio-technical transition governance and public opinion: The case of passenger transport in Finland. J. Transp. Geogr. 2015, 46, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratton, A. The role of talent development in environmentally sustainable hospitality: A case study of a Scottish National Health Service conference centre. Worldw. Hosp. Tourism Themes 2018, 10, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, D.; Salter, R. Direct Impacts of an Urban Living Lab from the Participants’ Perspective: Livewell Yarra. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van der Grijp, N.; van der Woerd, F.; Gaiddon, B.; Hummelshøj, R.; Larsson, M.; Osunmuyiwa, O.; Rooth, R. Demonstration projects of Nearly Zero Energy Buildings: Lessons from end-user experiences in Amsterdam, Helsingborg, and Lyon. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 49, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alade, T.; Edelenbos, J.; Gianoli, A. Frugality in multi-actor interactions and absorptive capacity of Addis-Ababa light-rail transport. J. Urban Manag. 2020, 9, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbloom, D.; Meadowcroft, J.; Sheppard, S.; Burch, S.; Williams, S. Transition Experiments: Opening Up Low-Carbon Transition Pathways for Canada through Innovation and Learning. Canad. Public Policy 2018, 44, 368–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barazza, E.; Strachan, N. The co-evolution of climate policy and investments in electricity markets: Simulating agent dynamics in UK, German and Italian electricity sectors. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 65, 101458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotilainen, K.; Aalto, P.; Valta, J.; Rautiainen, A.; Kojo, M.; Sovacool, B.K. From path dependence to policy mixes for Nordic electric mobility: Lessons for accelerating future transport transitions. Policy Sci. 2019, 52, 573–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stoll-Kleemann, S.; O’Riordan, T. Revisiting the Psychology of Denial Concerning Low-Carbon Behaviors: From Moral Disengagement to Generating Social Change. Sustainability 2020, 12, 935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bruine de Bruin, W.; Mayer, L.A.; Morgan, M.G. Developing communications about CCS: Three lessons learned. J. Risk Res. 2015, 18, 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hogarth, J.R. Evolutionary models of sustainable economic change in Brazil: No-till agriculture, reduced deforestation and ethanol biofuels. Environ. Innovat. Soc. Trans. 2017, 24, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkels, M.J.; Guillaume, J.H.A.; Leith, P.; Mendham, N.J.; van Oel, P.R.; Hellegers, P.J.G.J.; Meinke, H. Participatory Crossover Analysis to Support Discussions about Investments in Irrigation Water Sources. Water 2019, 11, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wiegink, N. Learning lessons and curbing criticism: Legitimizing involuntary resettlement and extractive projects in Mozambique. Polit. Geog. 2020, 81, 102192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, D.; Mangalagiu, D.; Thornton, T. Enabling Value Co-Creation in the Sharing Economy: The Case of Mobike. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goertz, G. Social Science Concepts: A User’s Guide; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, K.L. Etic and emic standpoints for the description of behaviour. In Communication and Culture; Smith, A.G., Ed.; Van Nostrand: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. American Psychological Association Dictionary. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/agency (accessed on 23 June 2021).

- Thaler, R.H.; Sunstein, C.R. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness; Penguin: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gigerenzer, G. Fast and frugal heuristics: The tools of bounded rationality. In Blackwell Handbook of Judgment and Decision Making; Koehler, D., Harvey, N., Eds.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 62–88. [Google Scholar]

- Giardullo, P.; Pellizzoni, L.; Brondi, S.; Osti, G.; Bögel, P.; Upham, P.; Castro, P. Connecting Dots: Multiple Perspectives on Socio-technical Transition and Social Practices. Ital. J. Sci. Technol. Stud. 2020, 10, 121–152. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, M.; Flinders, M. Rethinking depoliticization: Beyond the governmental. Policy Polit. 2014, 42, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, C. Why We Hate Politics; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Beverige, R.; Naumann, M. Global norms, local contestation: Privatisation and de/politicisation in Berlin. Policy Politics 2014, 42, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T.R.; Castro, P.; Guerra, R. Is the press presenting (neoliberal) foreign residency laws in a depoliticised way? The case of investment visas and the reconfiguring of citizenship. J. Soc. Polit. Psychol. 2020, 8, 748–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzemko, C. Energy Depoliticisation in the UK: Destroying Political Capacity. Br. J. Polit. Int. Relat. 2016, 18, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvidal-Røvik, T. Nature Articulations in Norwegian Advertising Discourse: A Depoliticized Discourse of Climate Change. Environ. Commun. 2018, 12, 794–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gailing, L.; Moss, T. (Eds.) Conceptualizing Germany’s Energy Transition; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cech, E.; Sherick, H.M. Depoliticization and the Structure of Engineering Education. In International Perspectives on Engineering Education; Veermas, P.E., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lucena, J. (Ed.) Engineering Education for Social Justice; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smerecnik, K.R.; Renegar, V.R. Capitalistic Agency: The Rhetoric of BP’s Helios Power Campaign. Environ. Commun. 2010, 4, 152–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, D.T.; Wals, A.E.J.; Jacobi, P.R. Learning-based transformations towards sustainability: A relational approach based on Humberto Maturana and Paulo Freire. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 1605–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romaioli, D.; Contarello, A. Redefining agency in late life: The concept of ‘disponibility’. Ageing Soc. 2019, 39, 194–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Typology | Definition | References |

|---|---|---|

| Social learning (in transitions studies) | Learning processes contribute to the generation of knowledge and expertise on how to improve innovations from experiments. However, besides this “first-order learning”, there is also a form of “second-order learning”, in which niche actors reflect on ongoing niche development and ongoing practices and critically question the assumptions of regime systems, learning about alternative cognitive frames and alternative ways of valuing and supporting niche development. | [65] |

| Social learning | Social learning: a process where two phenomena occur: first, changes in understanding appear in the individuals involved; and second, changes occur that go beyond the individuals and become situated within wider social units. Both these phenomena happen through direct and/or indirect social interactions among actors within a social framework. | [64]; Other examples: [70,71,80] |

| Situated learning | “Learning in the sense we use here means learning by people acting collectively to bring about radical and emancipatory social change”. Three key areas of activists’ adult learning, “instrumental learning—providing skills and information to deal with practical matters, ‘interpretive learning—which has a focus on communication’, and ‘critical learning’ —activists learn problem-solving skills through reflection new meaning is produced”. Informal learning occurs through the experience of being in a campaign and largely through reflection and action rather than in non-formal learning contexts such as workshops and training. Learning is embedded in the discursive interactions between members of the group; they are key pedagogic moments; they are moments of reflexive praxis and dialogic reciprocity, where knowledge-making occurs. | [63]; Other examples: [55,58] |

| Experiential learning | Learning effects take place both on supply and demand sides. On the supply side, they result from learning-by-doing, referring to increasing returns from knowledge accumulation and refined organizations. In this way, higher quality products and incremental innovations become cost-effective. On the consumption side, learning-by-using reduces the uncertainty of technology’s costs and performance, decreases service costs, and increases operation efficiency. | [75] Other examples: [61,74] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stocco, N.; Gardona, F.; Biddau, F.; Cottone, P.F. Learning Processes and Agency in the Decarbonization Context: A Systematic Review through a Cultural Psychology Point of View. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10425. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810425

Stocco N, Gardona F, Biddau F, Cottone PF. Learning Processes and Agency in the Decarbonization Context: A Systematic Review through a Cultural Psychology Point of View. Sustainability. 2021; 13(18):10425. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810425

Chicago/Turabian StyleStocco, Nicola, Francesco Gardona, Fulvio Biddau, and Paolo Francesco Cottone. 2021. "Learning Processes and Agency in the Decarbonization Context: A Systematic Review through a Cultural Psychology Point of View" Sustainability 13, no. 18: 10425. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810425

APA StyleStocco, N., Gardona, F., Biddau, F., & Cottone, P. F. (2021). Learning Processes and Agency in the Decarbonization Context: A Systematic Review through a Cultural Psychology Point of View. Sustainability, 13(18), 10425. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810425