Abstract

When looking at socio-technical systems from a systems thinking and systemic perspective, it becomes clear that mental models govern the behaviours and determine the achievements of socio-technical systems. This is also the case for individuals, being systems themselves and, as such, being elements of those socio-technical systems. Individual behaviours result from individual perceptions (mental models). These individual behaviours ideally generate the desired outcomes of a system (team/organisation/society) and create value. However, at the same time, mental models and the associated individual behaviour also bring about unwanted consequences, destroying or diminishing value. Therefore, to achieve safety and to attain sustainable safe performance, understanding and managing mental models in organisations is of paramount importance. Consequently, in organisations and society, one needs to generate the required mental models that create successes and, at the same time, to avoid or eliminate damaging perceptions and ideas in order to protect the created value. Generating and managing mental models involves leadership; leadership skills; and the ability to develop a shared vision, mission and ambition, as this helps determine what is valuable and allows for aligning individual mental models with those that preferably govern the system. In doing so, it is possible to create well-aligned corporate cultures that create and protect value and that generate sustainable safe performance. To achieve this aim, a systemic organisational culture alignment model is proposed. The model is based on the model of logical levels of awareness according to Dilts (1990), Argyris’s ladder of inference (1982) and the organisational alignment model proposed by Tosti (1996). Furthermore, ISO 31000 (2009, 2018) and its guidance are proposed as a practical tool to accomplish this alignment and sustainable safe performance in organisations. Altogether, these elements define Total Respect Management as a concept, mental model and methodology.

1. Introduction

1.1. Context

This concept paper is the third article in a row, with each step building further on a concept on achieving safety and performance in organisations proactively. These articles have been written in a way that they can stand alone. However, together, they form a concept answering three questions from the same coherent perspective on risk, safety and performance:

- How can risk, safety and performance be understood?

- How can risk, safety and performance be regarded from a systemic perspective?

- How can safety and performance be achieved proactively?

Together, the answers presented in these articles provide the perspectives and the mental models that help proactively achieve safety and performance in organisations.

As such, these articles contain the building blocks of a concept, an approach, we have named “Total Respect Management”. It is a systemic and integrated methodology useful in leading and managing any organisation in a volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous environment. This third article ties everything together and provides a brief view on what Total Respect Management entails.

1.2. A Systemic Perspective and Integrated Solution

In our article “Safety Science, a Systems Thinking Perspective: From Events to Mental Models and Sustainable Safety”(2020), we concluded the following:

“In our ever more complex and connected world, the safety of systems depends on the interactions and performance of the much smaller sub-systems. A proactive way to reach safety of systems is therefore to focus on the performance of the sub-systems at ever deeper levels of detail within the concerned system. It would therefore be interesting to study how mental models and these smaller subsystems relate and how they affect risk, safety and performance in the concerned socio-technical systems. Discovering appropriate empowering mental models, as well as finding relevant harmful mental models, would then allow to work with and develop mental models that generate safety and eliminate unwanted events. This should be made possible at an individual, corporate and societal level, to create an environment where people can be safe in any aspect of life.

To be able to do so, it is of the utmost importance to organise and structure dialogue to create and disseminate the corresponding mental models that generate and allow for this dedicated focus and attention to detail (the role of leadership). At the same time, it is important to discover how the sub-systems interact and create value or produce unwanted events that can be avoided (the role of risk management). Hence, it is necessary to simultaneously consider risk, safety (including security) and performance of even the smallest sub-systems and aim to reduce the number of failed objectives by continuous improvement, creating and maintaining safety in a sustainable way (the role of excellence)” [1].

In this third concept paper, we consider the different aspects of this conclusion, reflect on the role of mental models and establish ways to work with them.

- What are the challenges and the possible solutions when working with mental models?

- What about the mental models related to risk, safety and performance?

- How can safety and excellent performance in organisations be achieved?

To build further on our conclusions, we look at concepts such as “leadership” and ”alignment” to propose our own “Dynamic Cultural Alignment” and “Dynamic Organisational Alignment” models. Subsequently, we elaborate on how this model can be used as an instrument to create an aligned organisational culture, focussing on risk, safety and performance and working by means of dialogue, attention to detail, continuous learning and dedicated improvement, using the guidance contained in ISO 31000 as a practical tool.

1.3. Practical Approach of This Paper

First, we make clear how safety and performance can (and should) be understood in this context of organisational alignment, safety and performance and why leadership skills are of paramount importance.

Next, we expound upon the role of leadership in establishing alignment through determining and developing mental models in organisations, focussed on objectives and their achievement, and subsequently, we illuminate how the alignment of these mental models can be envisioned.

Finally, we explain how ISO 31000 [2,3] can be used as a tool in aligning mental models and in structuring dialogue in organisations, how this increases one’s quality of perception for better decision making and how this leads to continuous improvement. As such, ISO 31000 serves as a tool in achieving the desired alignment, the required focus and dedicated attention to detail, delivering the continuous improvement needed to reach safety and excellent performance proactively.

2. The Importance of Mental Models in Achieving Safety and Performance in Socio-Technical Systems

2.1. Systems, Mental Models and Levels of Perspective

Meadows described a system as a set of things—people, cells, molecules, etc.—interconnected in such way that they produce their own pattern of behaviour over time. She also stated that a system can be buffeted, constricted, triggered or driven by outside forces. However, the system’s response to these forces is characteristic of itself, and that response is seldom simple in the real world [4].

The consequence of this statement is that different systems—and certainly socio-technical systems—react differently to similar events, causing different results. When these results are “unwanted”, the best solution is not necessarily reactively putting barriers around the events to contain them but rather changing the system in a proactive way so that it produces different, “wanted” results instead of the “unwanted” outcomes.

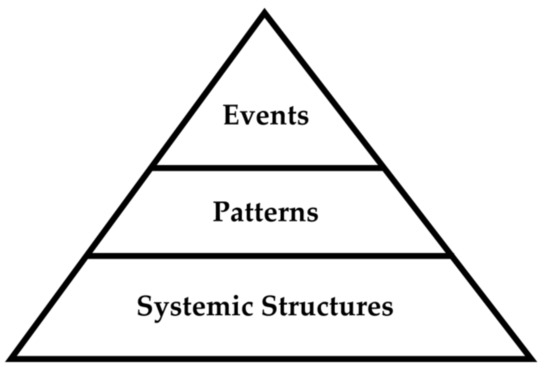

Kim [5] states that systemic structures generate patterns and events (Figure 1) but are very difficult to see.

Figure 1.

Systemic structures [5].

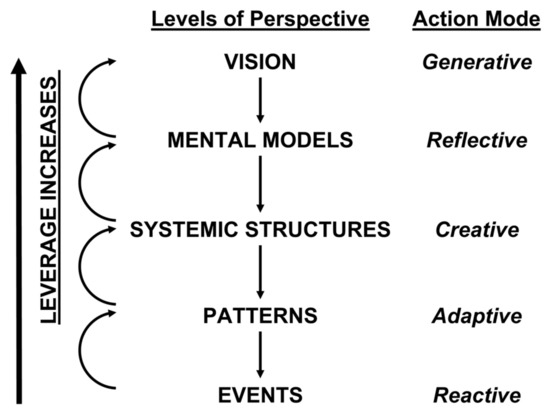

Kim also declared that a richer insight into systems can be gained by adding two more levels of perspective: mental models and vision. According to Kim, mental models are the beliefs and assumptions one holds about how the world works and, as such, they are the systemic structure generators. Vision, in his view, is seen as the picture of what one wants for the future and it is the guiding force that determines the mental models one holds as important when pursuing goals. He proclaimed that the levels of perspective framework (Figure 2) can help go beyond responding only to events and can begin looking for actions with a higher leverage and that each level offers a distinctive mode of action.

Figure 2.

Levels of perspective [5].

The most basic mode of action is “reactive” to counter events. More leverage is obtained when discovering patterns and when “adapting” to accommodate what is happening. A higher action mode is to act on the level of the “systemic structures”, for instance by redesign, reorganisation, reengineering, etc., and to be “creative” in doing so. However, successfully altering systemic structures often requires a higher leverage action mode and a change in mental imagination of what the new structures ought to be and what is to be changed. Therefore, the action mode becomes “reflective”, questioning one’s assumptions and building new mental models. According to Kim, the highest leverage is achieved on the level of “vision”.

However, changing mental models is a difficult and painful process, as mental models are the results of many years of experience and are difficult to alter. However, at the level of “vision”, new ideas can be envisioned, and the action mode becomes generative, bringing about matters that did not exist before.

According to Jones et al. [6], people’s ability to see and represent the world accurately is limited and unique to each individual. Therefore, mental models are incomplete and inconsistent images and interpretations that are context dependent. These mental models can change corresponding to specific situations at hand, adapting to continually changing circumstances and evolving through learning over time.

Although it is clear that a higher level of perspective offers the possibility of higher leverage, Kim [5] also indicates that not every issue needs a higher level of perspective to obtain a high leverage. There is the possibility of high leverage at every level of perspective, as this depends entirely on the issue at hand. For example, when a fire breaks out, it is best first to react very quickly to this event and to only seek higher levels of perspective and be more proactive in preventing fires breaking out afterwards.

Senge [7,8] stated the following: “the problems with mental models lie not in whether they are right or wrong. By definition, all models are simplifications. The problems with mental models arise when they become implicit, when they exist below the level of awareness and remain unexamined. Deeply entrenched mental models can impede learning and can overwhelm even the best systemic insights.” Nevertheless, bringing mental models to the surface and challenge them opens up opportunities and can accelerate learning.

2.2. Mental Models of Risk and Safety

How one perceives the concepts “risk” and “safety” can also be based on deeply entrenched mental models that possibly impede learning. For example, for some people, these concepts are considered antonyms, while others in past decennia have expanded their view on this matter.

Since the end of the previous century, these conceptions have seen an evolution in the ways we look at them, for example, as expressed in the ideas by Möller et al. [9], stating that safety is more than the antonym of risk, or by Slovic and Peters [10], who point out the importance of individual perceptions when dealing with risk. Furthermore, there are concepts such as Safety-I and Safety-II [11], where Hollnagel indicated that things going right is the larger part of safety but that this is rarely considered. In recent years, many scholars have approached these subjects from different angles, not necessarily coming to similar conclusions. More particularly, the introduction of a new (standardised) definition of risk a decade ago in the ISO 31000 standard has caused a lot of turmoil and discussion, dividing the world of risk specialists into believers and opposing non-believers that seem to dismiss this newer and broader definition of risk.

ISO 31000 defines risk as the “effect” of “uncertainty” on “objectives”. According to the ISO, an effect is a deviation from “the expected” and uncertainty is a state of (even partial) deficiency of information related to the understanding or knowledge of an event, its consequences or its likelihood. However, the ISO does not define the term “objectives”, and this is problematic, as this definition is only valid when the concept “objectives” is understood in its most encompassing sense. However, when one understands “objectives” being anything of value, anything a (sub)system needs or wants, one could say that this is the shortest and, at the same time, most complete definition of risk possible, as it incorporates all three elements that define risk in a most concise way. Anything added makes the definition more specific and less general and consequently subtracts from its meaning. Risk and “objectives”, “uncertainty” and “effect” can be considered similar to fire, which needs “fuel”, “oxygen” and a certain level of “heat” to exist. When leaving one of these three elements out, there is no risk. When an uncertain effect does not affect any objective, it is simply the probability of an event having likely consequences because no value is attributed to this event. When viewed this way, one can say that the ISO 31000 definition is an expansion of the traditional perspective on risk, including specifically the objectives at risk. Therefore, one could say that the intrinsic and expected value of an objective is now also incorporated in this broader definition, allowing us to include the possibility of both positive and negative effects on objectives, something that is missing in a traditional view on risk. Although one can argue otherwise, there is always room for improvement regarding a specific objective, opening up the positive side of risk.

As such, “the effect of uncertainty on objectives” (risk) is what can be considered the likelihood of an event combined with its likely associated consequences that can either be beneficial or detrimental to an objective or that can even be both at the same time. The question is not which mental model is right or wrong, but foremost what can be learned from a new and expanded mental model regarding the concept risk that mainly focusses on objectives rather than purely on uncertainties.

In his article “The risk game”, Slovic [12] already noticed that traditional approaches to risk assessment and risk management, where risk is viewed as an objective function of probability and adverse consequences of adverse events that can be objectively quantified, was insufficient, arguing for a new approach and highlighting the subjective and value laden nature of risk and its impact on decision making [13]. In his view, risk does not exist “out there”, independent from our minds and cultures, waiting to be measured [14]. He stated that humans invented the concept of risk to help them understand and cope with the uncertainties of life. Indeed, risk is about what humans value and each human values things differently. As such, the ISO definition of risk responds very well to the concerns expressed by Slovic.

For example, take a group of people going for a hike in the mountains. A traditional risk perspective focuses on possible events and, amongst others, evaluates the risk of falling rocks and the likelihood of impacting the group of people with all or some of its possible consequences. For a traditional approach to risk assessment, the risk is the same for every individual in the group, as they are all in the same situation. Traditional approaches do not consider the personal objectives of each member in the group because it is very difficult to know how every individual values their own “health and safety”. However, then, without knowing this value, the considered risk is just the probability of an event, and because the expectation is that rocks should not fall down on a group of people, every outcome is regarded as a negative outcome, as, generally, it is assumed that everyone values their health and physical integrity in the same way. However, arguably, this is not the real risk every individual takes or runs. With a focus on “objectives”, another, more diverse picture presents itself. Maybe there is a person in the group that has no objectives at all, no desires, no goals and no needs. This person could not care less what happens and does not care about life or death or injury. What is the real risk to this person? Maybe there is a person in the group that has a very imminent death wish because life is not what this person wants? Do these people run the same risk as a person that is looking forward to meeting their loved ones at the end of their journey? The value attached to the objective “life” determines the risk much more than any probability of an adverse event. Without these individual objectives, it is not risk that one deals with but just the probability of an (adverse) outcome that can be valued differently by different people. ISO 31000 defining risk as “the effect of uncertainty on objectives” provides a different, expanded view on the issue. Phrased in another (longer) way, one could also say that risk is that which makes maintaining and achieving one’s objective(s) uncertain because objectives and how they are valued matter in determining what risks are. The effect of uncertainty is about the things that could or could not happen and, as a result, impact one’s objectives. It means that the possible consequences of these rather expected or unexpected events influence the actual outcome of one’s objectives. Therefore, risk, in a sense, is a possible deviation of expected results regarding objectives. Of course, this deviation can be positive, negative or even both, depending on what objectives one considers, which time frame one observes and which value is expected because risk is a complex matter, related to an unknown future, concerning all of one’s objectives. These objectives can be not only conscious and explicit but also unconscious and implied.

For instance, one could consider two people, both playing the lottery. Both invest exactly the same amount of money, for example, EUR or USD 1000. A traditional perspective on risk calculates exactly what the risk is. The probabilities are known, and the value is also a given. However, is this the correct risk for both people, and is it really the same? This is impossible to know without further investigation because one does not know the value that the amount of money represents for that person. One also does not know the objectives that are involved in this situation for both people. What if one of those people is a multi-millionaire, for which EUR 1000 is just a number and of insignificant value. The risk is mostly positive because missing this amount of money does not mean much as no other objective is affected by the outcome of the event, while only winning is significant enough to make a difference. In essence, for this person, the risk is low, as the probability of gain is also very low. However, what would be the case for a person that invested all of their possessions in hopes of winning? Surely, for this person, a lot of his objectives are affected by the outcome of the event, making a huge difference between winning or losing. The risk for this person is mostly negative because the odds are not that good and losing that money can make a huge difference while winning can also make a huge difference, but this is highly unlikely. As such, the risk for this person is high, although the value of the money and the probabilities related to the event and its direct consequences are exactly the same for both people. Nonetheless, the risk for both is entirely different because the number and importance of the objectives that are affected by the end result are distinct. This example makes it clear that risk is, in the first place, about the objectives that can be affected and much less about the uncertainties involved, although both are important.

This approach towards risk and risk management, focused on objectives, is different from the traditional way, focused on uncertainties and probabilities. It requires a different way of assessing and dealing with risk. It is a different mental model concerning risk that also opens up a wider perspective on safety and performance when objectives are at the core of their definitions.

2.3. Looking at Risk Is Looking Proactively at Safety and Performance

How one looks at things is how one perceives reality and determines one’s mental models. As such, one also develops mental models of the concepts “safety” and “performance”.

In 1999, Rochlin stated the following:

“As is the case for risk, safety may also be defined formally or technically in terms of minimizing errors and measurable consequences, but it is more appropriate to adopt the principle used by Slovic in his social studies of risk and note that safety does not exist ‘out there’ independent of our minds and culture, ready to be measured, but as a constructed human concept, more easily judged than defined”.[15]

Le Coze stated that

“One of the major challenges in safety science is to develop methodologies and systems that are able to proactively capture and recognise situations and patterns that have the potential to provoke severe accidents. This instead of being obliged to use reactive approaches, such as learning from accident investigations when disasters already occurred”.[16]

In systems thinking, it is important to zoom out and to see how elements are linked or related and how they influence each other. It offers insight into what the dynamics are and how a system behaves. It is widely understood that risk and safety are related and that safety and performance are related. When looking at risk, safety and performance from a holistic “objectives” perspective, it becomes clear that risk, safety and performance are concepts dealing with the same thing: objectives.

Concerning the concept risk, this has been made clear by the ISO definition of risk. However, safety is also a concept that is linked to one’s objectives. Positive effects of uncertainty on one’s objectives are in general considered to improve one’s safety (Safety II thinking). Additionally, negative effects of uncertainty on one’s objectives are usually judged as being more unsafe (Safety I thinking). Similarly, the resulting value attributed to one’s objectives is what characterises one’s performance. When the effects of uncertainty and all other actions undertaken to reach, achieve or maintain an objective provide a negative deviation of the expected value of this objective, this is normally considered a bad performance, whereas a positive effect on those objectives is deemed a good performance. Looking at risk, safety and performance in this way and linking this with a time perspective, one could say that the state of one’s objectives at a certain time determines one’s risk, safety and performance (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Time perspective on objectives.

The possible (uncertain) effects on objectives seen in the future create and determine one’s risk. The possible (uncertain or not) effects on one’s actual objectives in the present characterises one’s safety. Finally, the actual effects on one’s objectives (in the past) defines one’s performance. In other words, risk, safety (in its most encompassing sense, including security) and performance are the same thing: the status of the effects on one’s objectives. The only difference is the time perspective that these different concepts represent [17].

Risk, safety and performance require a focus on objectives, being clear about what they are, how they can be valued and knowing how they can be managed. The ISO definition of risk immediately provides which elements need to be considered. First, there are the “objectives” themselves, and only then, there are the “effects” of “uncertainty” that can affect those objectives that can be treated and optimised.

Looking at objectives from different time perspectives to reflect risk, safety and performance and to understand that these concepts are fundamentally the same thing is a fundamental mental model and starting point for this concept paper. Positive effects increase safety and performance, and negative effects decrease safety and performance. However, the future makes these effects always uncertain, corresponding to the effect of uncertainty, whether these effects are perceived or not.

3. The Systemic and Integrated Perspective of the Cynefin Framework

3.1. Five Domains That Define One’s Quality of Perception

“Systemic” indicates a holistic view on reality. “Integrated” on the other hand means that various parts or aspects of an approach are linked and coordinated. The Cynefin framework, displayed in Figure 4, is a way to approach reality in both a systemic and an integrated way, delivering a clear view on one’s environment in its largest sense (which is the meaning of the Welsh word cynefin) and how to deal with this reality. As such, it offers insight into the methodologies needed to improve or alter the mental models related to one’s reality.

In a way, this model describes the different states of one’s quality of perception, meaning how well one understands a situation one is in and how well one’s mental models coincide with that specific reality. The framework distinguishes between order and disorder and uses these distinctions to match problems and their contexts with methods, tools and techniques that lead to solutions. While organisations seek order, stability and predictability, they also need a level of flexibility, adaptability and innovation to cope with an ever faster changing society and its reality. Cynefin helps in interpreting this reality and offers how to cope with this [18].

Figure 4.

Cynefin framework (inspired by [19]).

The framework divides reality in four specific domains. Each domain relates to the degree of complexity and the understanding of the reality one finds oneself in. The Cynefin framework’s value resides in the fact that it prescribes a set of behaviours and practices that are appropriate for a given domain. For example, it provides insight on how to think and act in order to move from complete ignorance (no mental model of the situation) and chaos (very confusing and jumbled mental models) towards the full understanding (clear, sharp and correct mental models) of reality in the simple domain. In essence, applying the steps in different domains, going from chaos towards simplicity, is about learning and adapting one’s mental models, which in turn helps increase one’s “quality of perception”. One can only perceive the reality one is confronted with, and thinking and acting in accordance with the different domains is appropriate and needed to increase awareness and understanding to achieve higher levels of perception.

3.2. The Importance of Leadership and Leadership Skills in Dealing with Mental Models

Another insight that the Cynefin framework offers is the kind of leadership behaviour fitting the different domains of the framework in order to obtain the best possible results of the actions taken. The model can be understood as follows (Figure 4).

The domains to the left of the model are referred to as being the “unordered” domains (complex and chaos), while the two domains to the right are also referred to as “ordered” (complicated and simple), where a certain order can be established [19].

Each domain is linked to the level of awareness and understanding of reality it represents, ranging from a complete lack of knowledge and understanding in the domain of so-called “chaos” to broad knowledge and understanding in the “simple” domain, after passing the complex and complicated domains, where knowledge and understanding is still lacking and where one still needs to learn. In the simple domain, everything is clear. Cause–effect relationships are fully known and understood. It is where the best practices reside. However, this is only the last phase of a learning process and often impossible to reach when situations are Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous (VUCA) due to the continuing change that organisations and society face today.

When one is unaware of things or unknowledgeable about matters, according to Snowden, one finds oneself in the domain of “chaos”. In this domain, one is unable to establish any cause–effect relationship, not even after events take place. Chaos first requires one to “act” upon events and, then to “sense” what happens and consequently to “respond” with appropriate actions to what occurred. In chaos, charismatic or directive leadership is needed to create a purpose (objective) and a direction to proceed in because, in chaos, one requires clear concepts (vision) and directions (purpose/objectives) in order to create structure and meaning. As soon as clear concepts and direction are established, one has to deal with the complexities that surround these objectives (risk). This requires a different attitude as one creates a form of order in chaos. It allows us to learn things and to move towards the complex domain. Here, one has to deal with the cause–effect relationships that could not be established beforehand, but which can be distinguished and studied afterwards when the effect of uncertainty on objectives turned into a performance that can be observed and investigated. In the complex domain, it is important to “probe” first, then to “sense” and finally to “respond” to what one has sensed. This typically is the domain of risk management, where the effect of uncertainty on objectives can be envisaged and where different scenarios or options can be identified and developed. In the complex domain, leadership is more of the supportive kind (paternal/matriarchal), focused on coaching and development, facilitating the exploration of new ideas, possibilities and innovation. This allows one to develop and move from the complex domain towards the complicated domain, as a sense of order emerges [19].

The right approach in the complex domain establishes order and leads to the “complicated” domain. Here, relationships between cause and effect are still not always very clear, but with some effort, they can be determined and studied before they produce outcomes. Once in the complicated domain, the approach should be “sensed”, “analysed” and “responded to”. Here, one requires less attention in the form of coaching, but gradually, as one’s self-leadership develops, there is a need for support and possibility participation in decision making itself. Therefore, in the complicated domain, a participative leadership style is a most appropriate way to conduct leadership. It is where analysis and evaluation of options and situations provide the possibility to continuously improve. Finally, one arrives at the lowest degree of (perceived) complexity in the “simple” domain. This domain is characterised by the fact that cause–effect relationships are “one on one”, easy to discern, known and understood. In the simple domain, the appropriate way to approach situations is to “sense”, “categorise” and “respond”. Therefore, in the simple domain, command and control are appropriate. Simple concepts neither allow for much room for interpretation nor provide the freedom the other domains offer [19].

A fifth domain, named “disorder”, is meant for moments and situations where one cannot clearly determine in which of the four domains one resides [19].

The different reasoning-in-action strategies summarised above underscore the capacity to continuously sense or monitor reality. In the ordered domains, this involves monitoring and feedback of fact-based-information, allowing for continuous improvement. In the unordered domains, this requires the capability to gather information and to discover events and patterns early enough so that a response to these new perceptions can be set up and attempted. Ideally, organisations discern these patterns while they are still small and emerging [20,21].

It needs to be stressed that the different domains relate to how well one knows and understands the matters one is dealing with. It is obvious that the more “VUCA” matters are, the more they are complex or even chaotic. However, even when matters are simple for one person, they can still be chaotic or complex for people with a lesser quality of perception regarding those matters. What is “simple” for specialists can be very “complex” for laymen. In Table 1, the insights the model offers are summarised.

Table 1.

Cynefin domains and their features.

As mentioned earlier, learning and development dictate one’s state of mind and the domain one is in, which is related to a situation one is in. The model also shows that leaders play an important role in the process of learning and increasing one’s quality of perception because leaders help people develop and improve their quality of perception using appropriate methods of reasoning and adopting the corresponding leadership styles for the people they lead, taking into account the domain these people find themselves in. Adequately adopting these different leadership styles requires a variety of leadership skills, ranging from developing a vision to which everyone can relate to a wide range of communication skills in dealing with the different levels of the quality of perception that exists in organisations.

In his article “What leaders really do” Kotter stated the following: “Leadership and management are two distinctive and complementary systems of action. Each has its own function and characteristic activities. Both are necessary for success in an increasingly complex and volatile (business) environment. Leading an organisation to constructive change begins by setting a direction—developing a vision of the future (often the distant future) along with strategies for producing the changes needed to achieve that vision” [22].

To put it clearly, “Leadership is creating a world to which people want to belong”. This quote by Gilles Pajou indicates what leadership really is about, which is creating an image of the future where people can relate to and for which they are willing to abandon the “world” they are currently in [23].

Another perspective on leadership is offered by Nicholls [24]. He stated that there are three fundamentally different perspectives of leadership. He defined these as Meta, Macro and Micro.

Meta leadership creates a “movement” in a broad general direction (such as clean energy, human rights or glasnost); it links individuals, through the leader’s vision, to the environment. It is the overarching vision that inspires and creates followers.

Macro leadership is the next step and is fulfilled in two ways: pathfinding and culture-building. Pathfinding can be seen as finding the way to the successful future that is envisioned. Culture-building can then be regarded as drawing people into a purposeful organisation, traveling along the chosen path and exploiting the opportunities that arise. Macro leadership influences individuals by linking them to the entity—be it the whole organisation or just a division, department or team—by giving answers to questions such as the following: What is our purpose or goal? What is my part in the story? What is in it for me? What is expected of me? Why should I commit myself and make an effort? In the process, the leader creates committed members of the organisation contributing to the cause.

Micro leadership on the other hand is about the choice of leadership style to create an efficient working atmosphere and to obtain the cooperation necessary in finishing the job by adjusting one’s style to directing people in organisations in the accomplishment of a specific job or task. On a micro level, leadership involves considering one’s individual state and capabilities with respect to the perceptual filters and motivations of one’s collaborators in order to define and achieve specific objectives in a particular environmental context.

One could say that meta leadership is required to allow people to leave the domain of chaos and that macro leadership is necessary to make sense of our VUCA world in the complex domain, but micro leadership is required at each of the perceptual domains that the Cynefin framework offers, related to the quality of perception one has at a specific moment and for the specific task executed to reach the destination that is envisioned.

“If the leadership style is correctly attuned, people perform willingly in an efficient working atmosphere, creating a world to which people want to belong” [24]. It involves a mixture of all three different perspectives on leadership and their associated aptitudes.

4. Organisational Alignment

4.1. The Importance of (Organisational) Alignment

“To have your ducks in a row”, “To put all the wood behind one arrow”, “Getting everyone on the same page”, and “Putting all noses in the same direction”: there are many expressions that indicate what alignment is about and what its purpose is. It is about bundling and streamlining ideas (mental models) and efforts in order to get better results. Thus, organisational alignment is the degree to which an organisation’s design, strategy and culture cooperate to achieve the same desired goals [25]. Organisational alignment is an inward-looking process that is crucial for organisational effectiveness [26]. Studies have revealed that the structural alignment of an organisation depends in part on the extent to which the objectives of the organisation are made clear to employees, as it helps to align their own goals with those of the organisation, facilitating the achievement of these overall goals. Employee enhancement plays a role in this process, as it assists in achieving the objectives by providing opportunities to improve necessary skills of individuals and to improve or clarify knowledge about their individual roles and goals. As a consequence, this allows for autonomy and involvement in decision-making processes, in a group or as individuals. Leadership is also of crucial influence in developing alignment. Leaders have to make clear that their co-workers operate in accordance with the organisational objectives. Studies have also indicated that leadership is more effective when leaders provide task-oriented guidance, so people know what is expected, and when they also demonstrate interpersonal (social) support and congruent behaviour. This is also true for upper management. When these conditions are met and alignment is achieved, this is most likely to positively influence organisational commitment and organisational satisfaction (the way people feel themselves fit in organisations). The opposite is also true, where a lack of alignment generates discomfort and reduces organisational and job satisfaction [27].

The importance of alignment and, more particularly, of the alignment of visions and objectives becomes even more obvious when one considers what, in general, causes the greatest dangers for society and organisations. Different visions lead to different mental models and, as such, generate different objectives. When these objectives are conflicting, negative effects of uncertainty arise. Terrorism, for example, is a very clear illustration of non-alignment of mental models and conflicting objectives on a societal level because many terrorist objectives are exactly opposite to the societal, organisational, and individual objectives they oppose [28]. Likewise, different visions and objectives between states and unions of states have always triggered conflicts and initiated wars with all their negative effects on individual, organisational and societal aspirations. However, also, within organisations, non-aligned or even conflicting objectives, deliberate or unconscious, are constant factors that generate effects of uncertainty on objectives (risk). They bring about adverse effects, affecting the objectives of the organisation or even society as a whole. In almost every major accident or disaster in organisations or society, non-alignment of objectives (conscious and deliberate, or unintentional and unaware) can be discovered as contributing factors. Therefore, it is of the utmost importance to align individual mental models in organisations, especially regarding vision, missions and ambitions with those of the organisation, as a first step in managing the effects of uncertainty on objectives in organisations because non-alignment of mental models and objectives is a major risk source that can and should be managed most prominently.

4.2. The Logical Levels of Awareness and Leadership

In “Applying systems thinking to analyse and learn from events”, Leveson [29] questions a.o., the mental model that assumes that increasing the reliability of individual system components also increases safety. She stated: “Safety and reliability are different system properties. One does not imply nor require the other. A system can be reliable and unsafe, or safe and unreliable. In some cases, these two system properties are conflicting, i.e., making the system safer may decrease reliability and enhancing reliability may decrease safety.” Giving examples of these objectives that sometimes conflict, she also stated that reliability is a component property but that safety is not. According to Leveson, safety is a system property and that, as complexity grows in the systems we operate in, accidents caused by dysfunctional interactions among elements of the system become more likely. As such, safety needs to be managed at a systems level and not at a component level. However, this does not mean that reliability as a component property in achieving safety is unimportant. There are too many examples that show that reliability is a key component property in achieving safety and performance. However, this is the case when the objectives of those key components are aligned with the overarching systems’ objectives. The ideas forwarded by Leveson, in the first place, underscore the importance of a systemic view on organisations before dealing with reliability, with a focus on the different objectives involved, their importance, how they relate and how they can be aligned.

One of the possible hierarchies that can be used to provide a quick judgement of the level of importance of an objective is the concept of the logical levels, attributed to Dilts and Bateson. Dilts [23] defined the logical levels as leadership skills in applying the concept of Bateson [30], who recognised “natural hierarchies of classification” in processes of learning, change and communication. Dilts [31,32] called logical levels “an internal hierarchy in which each level is progressively more psychologically encompassing and impactful” [33]. This means that an impact at a higher “logical level” is perceived as being more important. The scientific problem with the originally proposed logical levels is the fact that the upper levels, as defined by Dilts, are considered “spiritual” [34]. However, it is less of an objection when “spiritual” is replaced by “inspirational”. The inspiration of socio-technical systems lies in their purpose and the vision, mission and ambition that determine the objectives that matter and how they can be valued.

In their article “Organizational change: A critical challenge for team effectiveness”, Goodman and Loh [35] described the logical levels related to change. It provides a good basis on how an objective increases in importance when this concerns higher logical levels. The logical levels, in increasing level of importance, can be described as follows [36]:

- Environment is the lowest logical level and refers to what is outside the system: the place and time (where and when) the system pursues its objectives.

- Behaviour refers to specific actions: what each system does. This is the outward display of having successfully applied the key expected behaviours for achieving or safeguarding a particular objective.

- Capabilities are also referred to as “competencies”. These are the skills, qualities and strategies, that characterise the system. They are how actions of the system are executed. They often need to be defined, taught and practised in order to support the achievement and safeguarding of objectives. This also includes technology and other tools that are used to conduct specific behaviour and to reach specific results.

- Values and Beliefs (rules): “Values” are what an individual or team/system holds to be important, so they act as the drivers for what the system does. “Beliefs” are what an individual or team holds to be true and therefore influence what the system does and how it acts.

- Identity is how a system sees itself; it consists of the core beliefs and values that define it, and which provide a sense of “what the system is”.

- Purpose refers to the larger system of which the system is part. It connects to a wider purpose: “for whom?” or “what else?”

Using Dilts’ model of logical levels to distinguish different levels of importance in objectives therefore provides a powerful tool to determine and assess the impact of an objective on a socio-technical system. As such, the model offers a systemic view on individuals and organisations related to the alignment of objectives. Dilts [23] states the following:

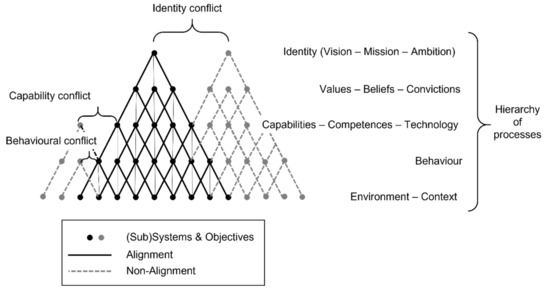

“Any system of activity is a subsystem embedded inside of another system, which is itself a subsystem embedded inside of another system, and so on. This kind of relationship between systems and subsystems naturally produces different levels or hierarchies of processes. The levels of process within a social system or organization correspond closely to the levels of perception and change that we have identified for individuals and groups—i.e., environment, behaviour, capability, beliefs and values, identity and ‘spiritual’. Each level of process involves progressively more of the system. Change in identity, for instance, involves a much more pervasive change (and, consequently, more risk) than a change at a lower level. It is a much simpler issue to change something in the environment or in a specific behaviour than to change values or beliefs.”

Figure 5 illustrates what Dilts declares. At each logical level, objectives can be noticed. The higher the logical level, the more important these objectives are because, the higher the logical level, the more subordinate objectives are involved at lower levels to achieve or maintain this higher level objective. This means that objectives situated at a higher logical level are more valuable.

Figure 5.

Logical levels—Inspired by Dilts [23].

Additionally, when systems and their objectives are not part or only partially part of the system’s higher logical levels, non-alignment occurs (Figure 5). Most problematic is when this non-alignment turns into a conflict. The higher the level on which this conflict occurs, the more conflicting objectives become involved, creating more negative risks, unsafety and a lack of performance for the concerned system(s).

4.3. A Dynamic Cultural Alignment Model—Flywheel of Alignment

One can also consider the hierarchy of logical levels from a “mental model” perspective and relate it to individuals and organisations. It shows how mental models can determine situations and action. How one looks at reality determines what is important not only to individuals but also to organisations. Purpose comes from a vision that translates into a mission and ambition. To become aware and to build a clear, unified and shared vision of reality therefore become of paramount importance in aligning the logical levels. This is both valid for an individual perspective as well as an organisational view on reality.

Although Dilts considers “Identity” as a separate level, one could also consider “Identity” as being the whole of all logical levels together (Figure 6). People identify themselves by their environment, where they come from (region, nationality, culture, etc.), what they do or the competences they have (e.g., being a painter, a researcher, a taxi driver, etc.). One also identifies people by the values and beliefs they adhere to (religion, politics, nutritional choices, etc.). Additionally, all of these “characteristics”, at different logical levels, shape the filters with which the world is viewed. For individuals, the higher levels of awareness are difficult to become aware of. What exactly one’s purpose is, how this relates to reality and how one views this reality is something one, in general, does not contemplate about. It is why people end up in situations they are not happy about, as the perceived reality of their environment does not fully correspond with these higher levels of awareness, creating a lack of alignment and generating conflicting objectives. By itself, people have different “role identities” related to what one does but one rarely discovers one’s true identity, aligned with the inspiring purpose that energises and fulfils one’s aspirations.

Figure 6.

Based on the logical levels of awareness Inspired by Dilts [23].

The same is true for organisations. Here, one can say that, instead of “true identity”, one can consider the whole of all logical levels as being the “true culture” of the organisation. The more these levels are aligned, the easier this culture is recognised and the stronger it becomes.

Today, most successful organisations are aware of the importance of common values that are characteristic of the organisation and that need to be respected by its stakeholders. However, although shared values are very important, it is only an alignment at a lower logical level that is pursued. Shared values do not necessarily represent shared ambitions or a shared mission. In general, shared values lack the power of inspiration and should rather be a result than an aim in and of itself. Much more powerful are the shared vision, mission and ambition because, when mental models at this level of awareness are shared and recognised, they become a persistent force and guidance for all members of the organisation. This force and this guidance boost safety and performance when they are values that are aligned with and have been recognised in the vision of the organisation [37].

Dilts also emphasises the following:

“One of the most important aspects of effective and ecological communication and change is the congruence between the ‘message’ and the ‘messenger.’ On a personal level, a healthy and effective person is one whose own actions are aligned with his or her capabilities, beliefs, values and sense of identity or mission. A person’s sense of role and identity is a dynamic process related to several different factors:

The concept of different ‘levels’ of change provides us with a powerful road map for bringing the various dimensions of ourselves into alignment in order to realize our goals and visions. Each of these different levels is embodied through successively deeper and broader organizations of ‘neural circuitry.’ As one moves from the simple perception of the environment, for instance, to the activation of behaviour within that environment, more commitment of one’s mind and body must be mobilized”.[38]

As indicated earlier, the key to successful change and organisational alignment is an inspiring vision. A vision of the past, present and future reveals a path to a better future that people want to belong to. This is for individuals and organisations alike because individuals are at the core of any organisation, as it is their mental models that shape and govern the organisation. Building a shared vision in organisations is creating a shared understanding of the deeper purpose of the organisation and its destiny because not all visions are equal. Only visions that tap into this deeper sense of purpose and that translate into the objectives of a mission and ambition fitting the organisation make this vision and purpose genuine and true. It then has the power to generate aspiration and dedication to belonging to the world envisioned. However, this vision also needs to come from the people who care for the organisation and who have a collective sense of its underlying purpose. Building a shared vision therefore is a process that requires respect, openness and dialogue at every level of the organisation. It is the construction of a common understanding of a shared map of reality and the deliberate choice of an itinerary to an inspiring and engaging destination [7,8].

The importance of developing this common purpose, where corporate goals also become personal objectives is supported by Berg. In his article “The role of personal purpose and personal goals in symbiotic visions” [39], he stated the following:

Engagement was defined by Bakker, et al., as a positive and pleased state of mind, categorized by vigour, commitment, and captivation, commonly understood to generate higher levels of energy and a strong connection to work. Boyatzis, Smith, and Beveridge also connected engagement with increased energy, focus and drive through their research on “Positive Emotional Attractors. (PEA)” They validated this theory by linking PEA to physical stimulation—identifying the physiological activation that occurs during the actual experience of an elevated state of engagement, hopefulness, and future orientation. When reaching for a personal vision one is engaged, emotionally and physically, in moving toward an overarching goal. The goal becomes meaningful and purposeful enough to impact their energy, their focus and their drive. This is also supported by the evidence that the desire to achieve one’s “ought self,” or the self that we feel we ought to be, is less than the desire to reach for our ideal self. When we are working to accomplish a goal or vision that is not our own, we are less driven.

Vision and how one views reality are closely related to the attitude one adopts when looking at the past, present or future. The ladder of inference (Figure 7) [7,40,41] is a common mental pathway of increasing abstraction, often leading to misguided beliefs. The only visible parts are the directly observable elements, which are the data at the bottom of the ladder and the actions resulting from decisions at the top of the ladder. These actions are the result of self-generating beliefs that remain largely untested. One adopts those beliefs because they are based on conclusions that are inferred from what one observes, added to past experiences [42]. The ladder of inference provides insight in the way people perceive reality as it is and which attitude they have developed due to this perception. For example, when situations are perceived to be satisfactory and good enough, this focus provides evidence for this inference and anything that contradicts this conclusion is dismissed. Hence, it is difficult to create a vision of better and more, as the need for improvement is not perceived and the attitude is one of acceptance of a status quo. However, a different reality can be perceived when it is possible to establish the mental model that, within a certain context, everything can and should be improved whenever possible. In other words, there is always room for improvement and it is also a moral obligation to pursue excellence. Elements requiring improvement are noticed and a changed attitude, with a focus on improvement, is developed. This altered attitude in its turn allows for the development of a new perception of reality. This perception creates a vision concerning the need for a better future, requiring improvement and change [37].

Figure 7.

Ladder of inference according to (a) Argyris [40,41] and (b) Senge [8,42].

A first and crucial phase in alignment in organisations is discovering and altering individual attitudes, and aligning them as much as possible with the attitude that the organisation needs. Kotter [22] stated that alignment is more of a communication challenge than a design problem. Alignment always involves talking to many individuals. This involves not only subordinates but also supervisors; peers; staff in other parts of the organisation; as well as other stakeholders, such as suppliers, government officials or customers. Anyone involved in implementing a vision and its associated strategies or who can help or impede implementation can be relevant. This is a huge communication challenge because alignment messages are not automatically accepted just because they are understood. It all depends on credibility. One has to believe the story. Credibility, amongst others, depends on the background of the person delivering the message, the content of the message itself, the communicator’s reputation regarding integrity and trustworthiness, and the consistency between words and deeds. Leaders need to “talk the walk” and most certainly “walk the talk” when they seek alignment. They are the first example. Managing organisations with design of systems and structures helps normal people complete routine jobs successfully, every day. Leadership however has a different calling. It is about achieving grand visions, which continuously involves a lot of energy. Therefore, it is the leader’s duty to motivate and inspire people to energise them. This does not happen by pushing them in the right direction, as control mechanisms do, but by paying attention to fundamental human needs such as a sense of belonging, recognition and self-esteem because fulfilling these needs provide a sense of achievement, a sense of control over one’s life and the power to live up to one’s ideals [22]. These emotions touch people profoundly and therefore provoke powerful reactions that trigger the right attitude to expand one’s reality and to understand and welcome the new reality presented by the vision of the leader.

This first crucial step in organisational alignment is represented in Figure 8a, where leaders have to confront the mental models and ladders of inference of their “followers”. They have to show people a different and more inspiring reality, provoking the right attitude to embrace the vision the leader develops. It is the fundamental “why” that Sinek talks about in his book Start with why: How great leaders inspire everyone to take action [43]. Once this most difficult step is achieved, the organisational alignment can follow the hierarchy of logical levels, determining the objectives at each logical level aligned with the objectives of a higher level. Again, this is a communication challenge, where leaders need to communicate in the form of dialogue to choose the appropriate objectives people believe in. At a strategic level, this involves the mission, ambition, and values and convictions that are important to achieve what is envisioned (Figure 8b). In that regard, Canals [44] declared:

“Leadership development programs should either have a clear purpose in terms of their design and goals or may end up in an expensive and sometimes useless initiative that consumes people’s time and resources, and may generate a cynical view of the diverging pathways between the firms’ mission and the real life in the organization. Moreover, leadership programs should also help participants understand better the implications of the firm’s mission on the different corporate policies and decisions regarding customers, people, shareholders and other stakeholders, and the corporate culture and values that should be present in making those decisions.”

Figure 8.

(a)Ladder of inference (Direction and orientation.), (b) Strategic alignment (Overarching objectives) and (c) Operational alignment (Specific and detailed objectives).

What can be named a “mission” is the action required to close the gap between the current reality and the envisioned future, while the ambition translates the identity of the organisation into objectives. Surely, the ambitions of a multi-national organisation completely differs from a local SME with only a local reach; in the same way, this is completely different from a public service or a government agency. At the operational level, these strategic objectives translate into the objectives regarding competences (including technology), behaviour and context needed to achieve the overarching objective and aligned with the higher strategic logical levels (Figure 8c). The mental models developed at the strategic level dictates what is necessary and in line with the adopted vision, mission and ambition, congruent with the values and convictions that support the vision. At each level, each step is a feedback loop in itself. The most prominent influence moves clockwise. However, a counter clockwise influence can also be present. Together, they are needed to adapt and improve where necessary and to make the alignment more powerful.

The loops described above form a whole. They connect the ladder of inference with the strategic component, which results in the operational component, in the form of parts of the process, creating an aligned identity and a corporate culture [37]. In essence, the three loops form an individual leadership process when each step is used to align oneself with the vision one adopts, resulting in aligned leadership, congruent with one’s vision. At the same time, these steps can also be used as the levels of change to lead people in volatile, uncertain and complex situations, as all three elements together form a dynamic organisational culture alignment model, with which an organisation can align itself and its stakeholders with its vision (Figure 9). The better this alignment is executed, the stronger the corporate culture becomes, aligned with the vision, mission, ambition and values that matter. When high performance and safety are important values, this should automatically involve a specific attention to risks related to the objectives present at all logical levels of the organisation (Cfr. Section 2.3).

Figure 9.

Dynamic cultural alignment model—flywheel of alignment [37].

4.4. A Dynamic Model to Align Organisational Strategy and Culture

The flywheel of alignment is an instrument of vertical alignment in organisations, aligning individuals, and the organisation as a whole to create a strong corporate culture. However, organisations also develop strategies to reach their aims. Both strategy and culture need to work in concert to perform well. Still, the statement “Culture eats strategy for breakfast” (attributed to Peter Drucker post-mortem 2006) indicates that a strategy chosen by higher management can easily be dismissed due to an organisational culture that is not aligned with the strategy taken. This claim also indicates that it might be meaningful to spend efforts picking or developing the right strategy to reach one’s objectives and to align it as close as possible with the existing corporate culture. However, it is also possible to enhance the organisational culture to fit a desired strategy first, for instance when this is needed as a result of a merger or another crucial change in the organisation [37].

In their book Strategy synthesis, De Wit and Meyer [45] stated that there is no such thing as a common understanding of what strategy is. They even said that a sharp definition of strategy would be misleading, as there are so many different and strongly differing opinions on most of the key issues. The presence of these conflicting views indicates that strategy cannot be summarised into a widely accepted definition. However, complexity theorists define strategy as the unfolding of the internal and external aspects of the organisation that result in actions in a socioeconomic context. As such, one could say that strategy consists of selected organisational arrangements an organisation needs and uses to achieve its aim. Most organisational alignment studies deal with aligning these organisational arrangements with the chosen strategy. For instance, how can IT solutions (tools) support the organisations processes or what kind of processes are necessary to achieve the strategic aims. However, these punctual alignment issues focused on strategy often miss the systemic approach that is necessary to align these solutions to the people and the corporate culture they represent. Ideally, these organisational arrangements also fit the culture that identifies the organisation.

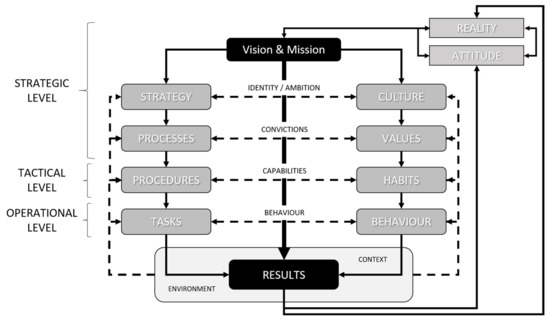

A model that considers this aspect of alignment is the organisational alignment model proposed by Tosti. He stated: “The concept of alignment applies to both the external alignment of the organizations with its community, marketplace, and business environment, and the internal alignment of the organizations across the levels of administration, operations and job. Internally the organization should be aligned around the results the organization is striving to achieve” [46]. According to Tosti and Jackson, organisational alignment is connecting strategy, culture, processes, people, leadership and systems to best respond to the demands of the organisation. Organisational alignment requires compatibility between the strategic and cultural pathways and necessitates consistency within them (Figure 10) [47].

Figure 10.

Organisational alignment model [46].

Amarant and Tosti [48] stated that thinking systemically, viewing performance as the result of a system is essential to performance improvement because performance is a function of all of the systems’ variables. Reducing attention to actors overlooks most important sources of performance variance that occur at other levels of the organisation. They identified three levels of organisational complexity:

- Organisational Level (Goals/Values). An organisation is a dynamic entity that must be managed and governed by people. This requires executives, functional managers and administrative systems to lead the organisation as a whole.

- Operations Level (Processes/Practices). The processes that guide people’s work are intended to convert inputs into goods or services that provide customers with value. Within each process are sequences of tasks that are supported by management.

- People Level (Tasks/Behaviour). The actor is central to the system [48].

Tosti stated that results depend not only on the processes people follow but also on how one behaves when executing those processes (practices). Behavioural practices of groups and individuals can make the difference between merely adequate results and outstanding results. In the worst case, poor practices can destroy good processes. He believed that creating and maintaining a balanced and aligned organisation requires decisions about both organisational direction and intent and regarding what is important about the way it operates. This responsibility of the organisation’s leadership constitutes a critical factor that needs to be considered in attempts to improve performance because they have the broadest impact on mobilising the organisation to succeed. However, there is little attempt by many organisations to ensure that these practices are aligned with the desired results [49]. Strategy is implemented tactically by making sure that the three levels of organisational complexity are vertically aligned to achieve results. This is performed to the design and execution of operational processes. This requires using the strategy and mission as a means of aligning goals and objectives, then aligning processes with those goals, and finally aligning the tasks that people perform with the processes [46].

When one combines their knowledge of the organisational alignment model and the insights of the flywheel of alignment, one can construct a dynamic organisational alignment model, as depicted in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Dynamic organisational alignment model [50].

In the central top to bottom arrow of the model, one can find the logical levels of the individual stakeholders {XE ``stakeholders''} making up the organisation. Ideally, these individual logical levels are based on a shared vision {XE ``vision''} and mission {XE ``mission''}, leading to individual but aligned ambitions, connecting the individual identities to a corporate identity {XE ``identity''} and culture. On the right side of the model, the organisational culture is represented by all of its components, while on the left side of the diagram, the column represents the elements that make up a strategy. How stakeholders perceive their results and the organisational context and how a culture and a strategy feed into reality {XE ``reality''} is represented by the closed loop of attitude and reality, explained earlier as the function of one’s ladder of inference and of the flywheel of alignment. This element of attitude and perception of one’s reality closes the loop connecting the actual results that are achieved in a specific organisational context, with the overall (shared) vision and mission of the organisation and its stakeholders. When vision, mission and ambition are clear and powerful, the mental model {XE ``model''} is created, and alignment can start [50].

5. ISO 31000 as a Practical Tool to Reach Alignment, Safety and Performance in Organisations

5.1. Observations Regarding ISO 31000

From the beginning of this century, noteworthily, focus on risk management increased. There is a great conviction that risk management provides a fitting tool for assessing the conflicts inherent in exploring opportunities (to create value), on the one hand, and avoiding losses, accidents and disasters (to protect value), on the other [51].

In their article “Implementing Bayesian networks for ISO 31000: 2018-based maritime oil spill risk management: State-of-the-art, implementation benefits and challenges, and future research directions”, Parviainen et al. [52] stated:

“The ISO 31000:2018 International Standard on Risk Management (ISO 2018) provides guidelines for integrated risk management for all types of organizations and is therefore in essential role in communication of academia and industry. The use of the ISO 31000:2018 standard has also been suggested as a suitable basis for the evaluation of Pollution Preparedness and Response (PPR) risk management and for dealing with uncertainties when assessing oil spill risks in industry activities. As the main focus has been on industry activities, there is a need to improve the link of the academic scientific work to the ISO 31000:2018 standard.”

The title of the ISO 31000 standard [2,3] is “Risk management—guidelines”. It is a guidance standard on how to manage risk in organisations independent of the size, sector or industry to which the organisation belongs. Unfortunately, this standard is often disputed, and it seems that it is not always properly understood by some risk specialists. Mostly, the critique is in regard to the elements of the proposed vocabulary and seems to be based on the mental models that governed risk management in the twentieth century. This mental model is based on the early developments of risk management in the financial/insurance industry, focused on loss, and the engineering world, focused on component reliability. This mental model is based on uncertainties in the form of probabilities and statistical evidence (cfr. Section 2.2). Regarding their criticism, Olechowski et al. [53] stated the following:

“A number of authors have critically examined the ISO 31000 standard as a whole. Aven (2011) critiques the uncertainty- and risk-related vocabulary of the standard from a reliability and safety point of view. The author argues that the guide fails to provide consistent and meaningful definitions of key concepts. In a broader critique of the standard, Leitch (2010) concludes that the standard is vague and lacks a mathematical base. He attributes the vagueness to the process, given that the standard was created from a consensus-based process involving people from all over the world, speaking different languages. Although it is important to conceptually examine the fundamental definitions on which the standard is built, neither of these papers involve actual evidence to evaluate the effectiveness of the ISO 31000 standard, and its potential for impact in industry.”

The experts in risk assessment accustomed to this twentieth century mental model employ various, often complex, mathematical models to calculate the levels of risk for very precise and well-defined objectives related to the reliability of components of a system, where a deviation from an expected result is always negative. Seen from this twentieth century mental model regarding risk, this critique is therefore understandable and, for engineering and component reliability, the objective and the cause–effect relationships are always apparent. It is a consideration for risk on a component level. This type of risk management is the domain of experts who often work in specialised departments in organisations, often in a silo context, where risk management is separate from other departments or operations of the organisation.

However, while entirely suited to assessing the risks related to the reliability of components of a system, this mental model regarding risk is inappropriate for the VUCA that world organisations operate in. This became noticeable in the second half of the twentieth century when a number of events showed the inability of these risk management silos to cope with the changing realities, and the variability and management of objectives in organisational operations. New paradigms regarding risk and risk management with a broader, more systemic focus emerged. It is a different perspective on risk, based on a different mental model, leading to concepts such as Operational Risk Management (ORM) or Enterprise Risk management (ERM) and, ultimately, ISO 31000 as an overarching set of mental models regarding the management of risk in organisations and even for society as a whole. These concepts, which are more focused on objectives involved with systems instead of the restricted view on the components of a system, also focus on the creation of value instead of solely trying to protect value, with an understanding that results can surpass expectations [17].

In the same article, Olechowski et al. [53] also stated:

“Empirical evidence from the statistical analysis suggests that the ISO 31000 is indeed a promising guideline for the establishment of risk management in the engineering management community. Adhering to the risk management principles at a high level was found to be a significant factor in better reaching cost, schedule, technical and customer targets, in addition to achieving a more stable project execution. We believe that this provides evidence of the potential for the principles to form the basis of a project risk management body of knowledge and to have a strong impact on the professionalization of the risk management function.”

The twentieth century perspective comes from a risk analysis point of view. However, “risk analysis” is just a component of the system “risk assessment”, which in turn is only a component of the overarching system “risk management”. Looking at ISO 31000 from an analysis perspective therefore does not make sense because risk management is so much more than the analysis or assessment of risk. In fact, ISO 31000 involves even more than just management. It covers all domains of the Cynefin framework and involves leadership as much as management.

Lalonde and Boiral [54] stated:

“The new ISO 31000 risk management standard makes several important contributions to a field that still has relatively few benchmarks. On the one hand, the generic nature of the standard may help to better identify and manage a variety of risks including threats to the environment, public health and food safety issues, threats to critical infrastructure, hazards presented by certain products, and interruption of the supply chain. This diversity of risks tends to broaden the scope of the standard’s applicability to a wide range of situations and organizations. On the other hand, the standard suggests a methodical and structured approach to how to manage risks. As Purdy points out, while this approach may seem relatively conventional, the standard does succeed in integrating into a single concise and practical model a considerable amount of knowledge accumulated from research on multiple aspects of the field which is widely scattered in the literature and thus difficult to take into account.”

Additionally, other authors welcome this broader view on risk management. In their article “Risk management in public sector: A literature review”, Ahmeti and Vladi [55] concluded:

“The key finding of this research was that risk management is neither an optional nor a volunteer tool in the whole management of an organization; it is a must for every type of organization if they want to assure the achievement of their strategic goals and objectives. Risk is a threat or an opportunity, which cannot be eliminated completely and requires an effective management. Accordingly, our risk attitudes and risk perceptions may be influenced by a number of factors—even if we are not aware of such an influence.”

Furthermore, in an article “Analysis of international risk management standards (advantages and disadvantages)” [56], the authors declared:

“In conclusion, ISO 31000, besides being a very effective tool for enterprise risk management, is also applicable as a base for more specialized standards. Consequently, it is important that these standards have the same basis or comparable to the ISO 31000 standard, especially in terms of the vocabulary and terminology used. The creation of ISO 31000 is motivated in particular by the fact that the risk management industry has always applied a variety of standards for risk management and also the terminology used has unmet standardisation, thus making communication of risk information more difficult. Despite the numerous of criticisms of this standard, its contribution to better risk management in the organization remains indisputable”.