Ecolabeling as a Policy Instrument for More Sustainable Development: The Evidence of Supply and Demand Interactions from Russia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Theoretical Foundations and Empirical Evidence of the Problems in Ecolabeling: Literature Review

3. Methods and Data

3.1. Analysis of the Prevalence and Information Content of Ecolabels on Everyday Goods in Russian Supermarkets (Supply Side of the Market)

3.2. Analysis of Consumers’ Recognition and Attitude toward Ecolabels

4. Results and Discussion

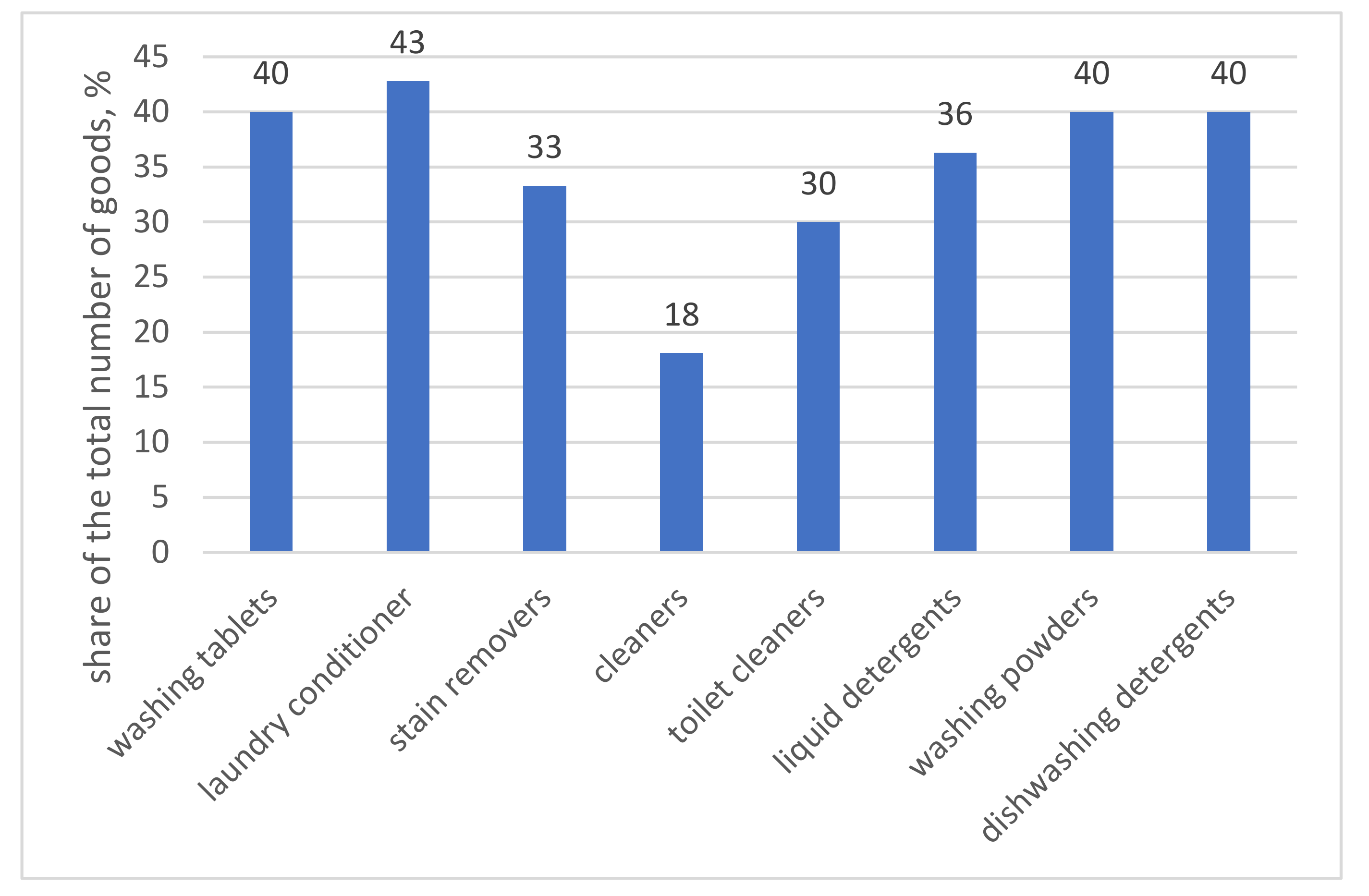

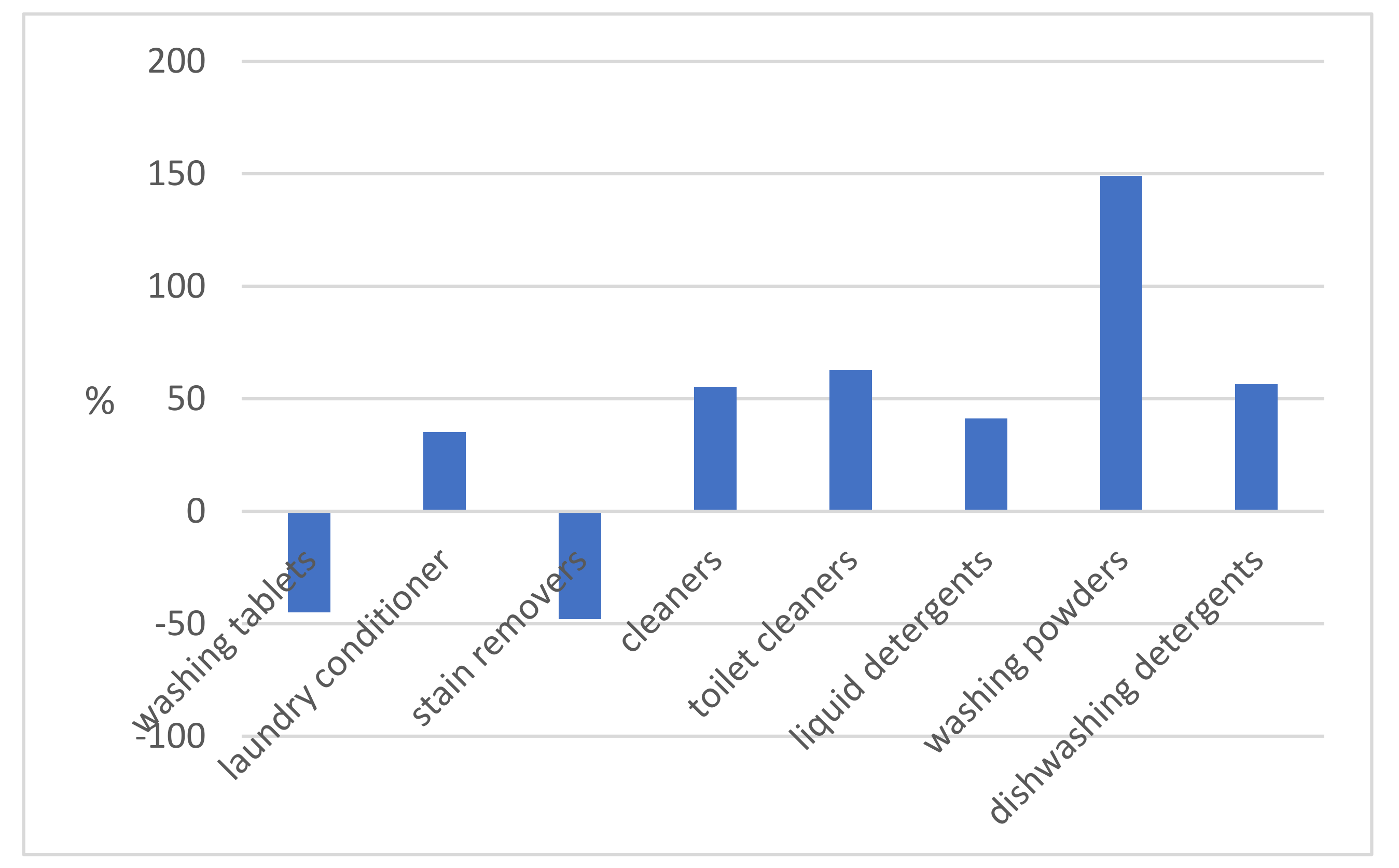

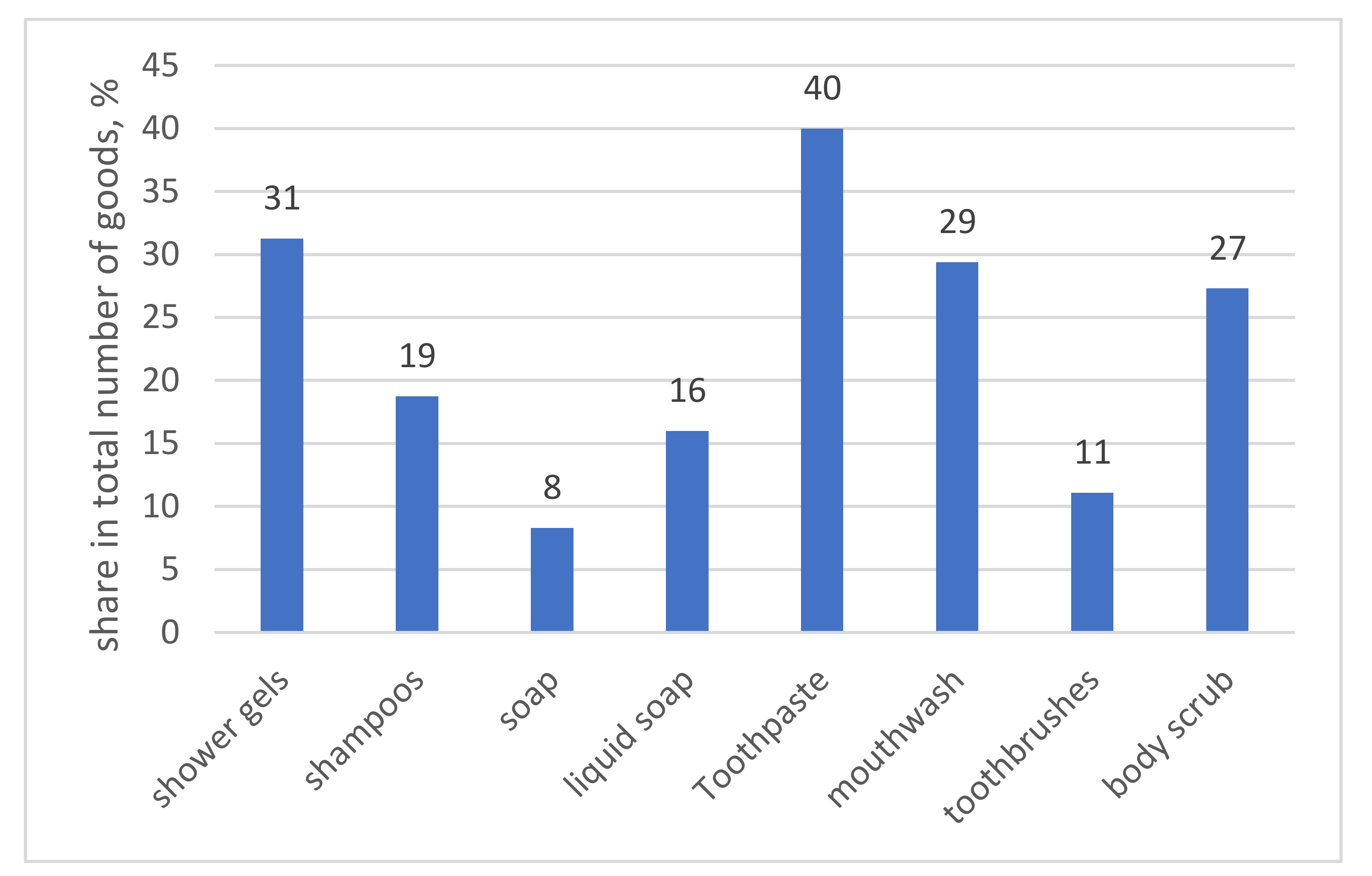

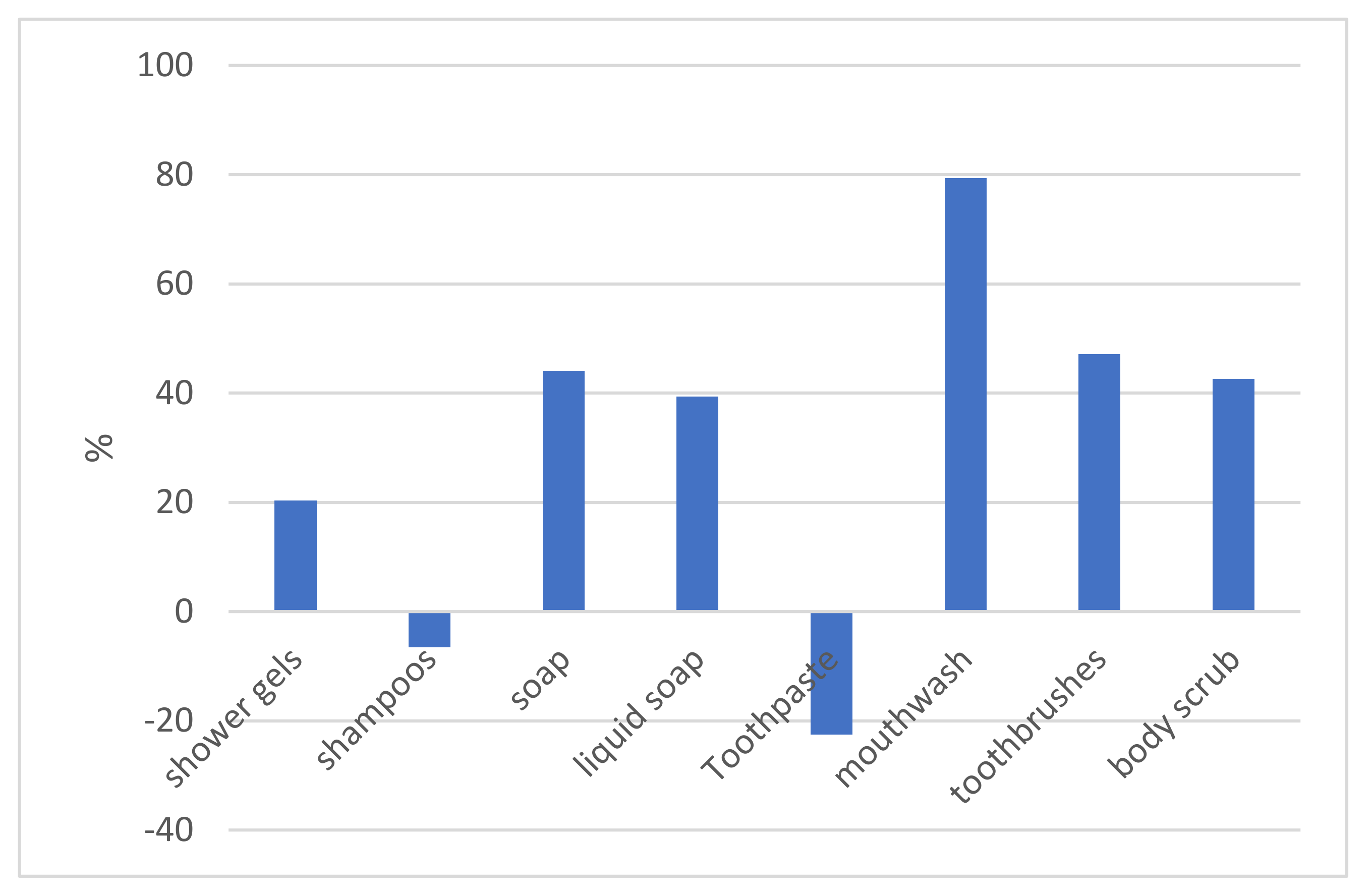

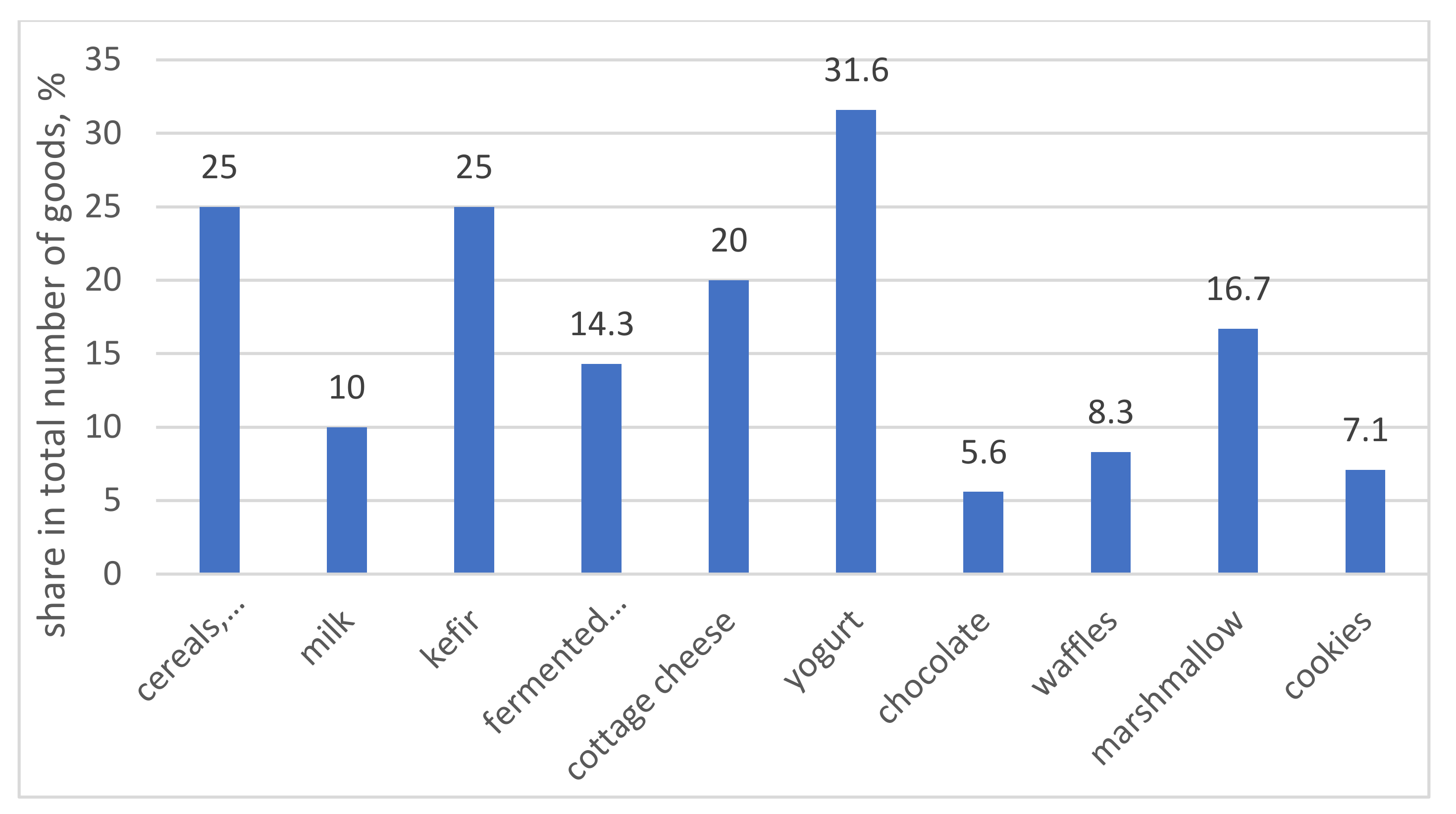

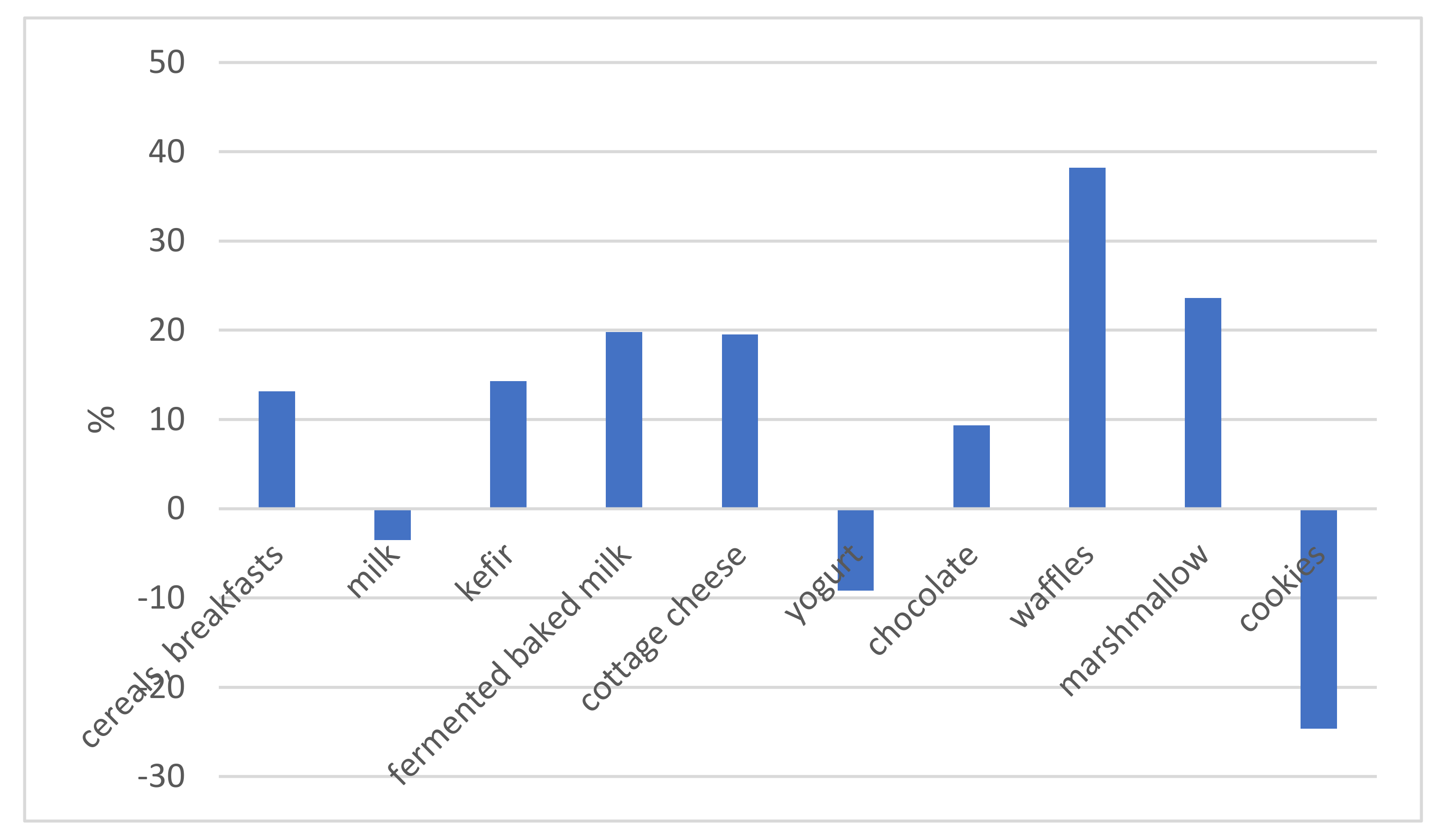

4.1. Supply-Side Study of Ecolabeled Goods in Russia

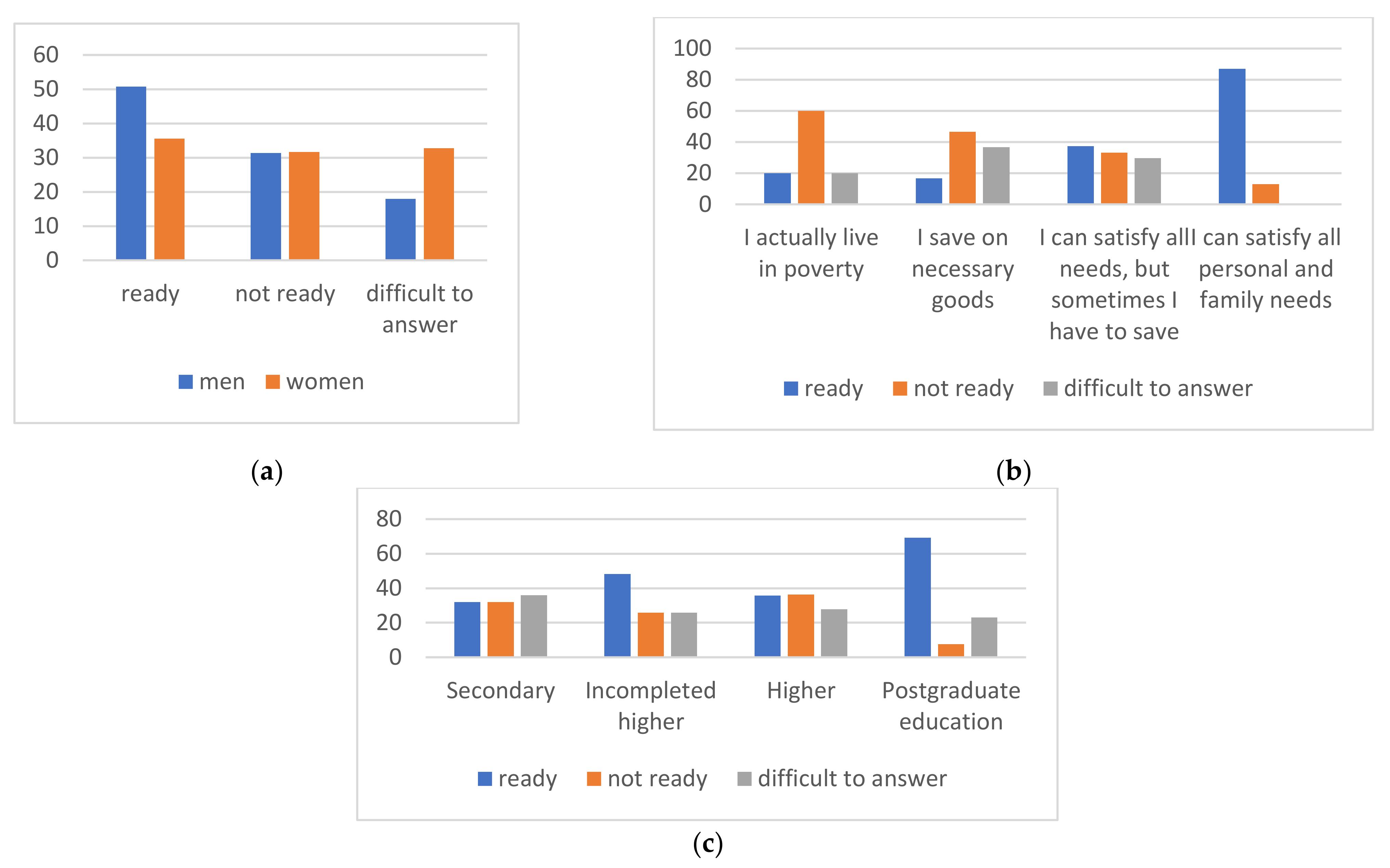

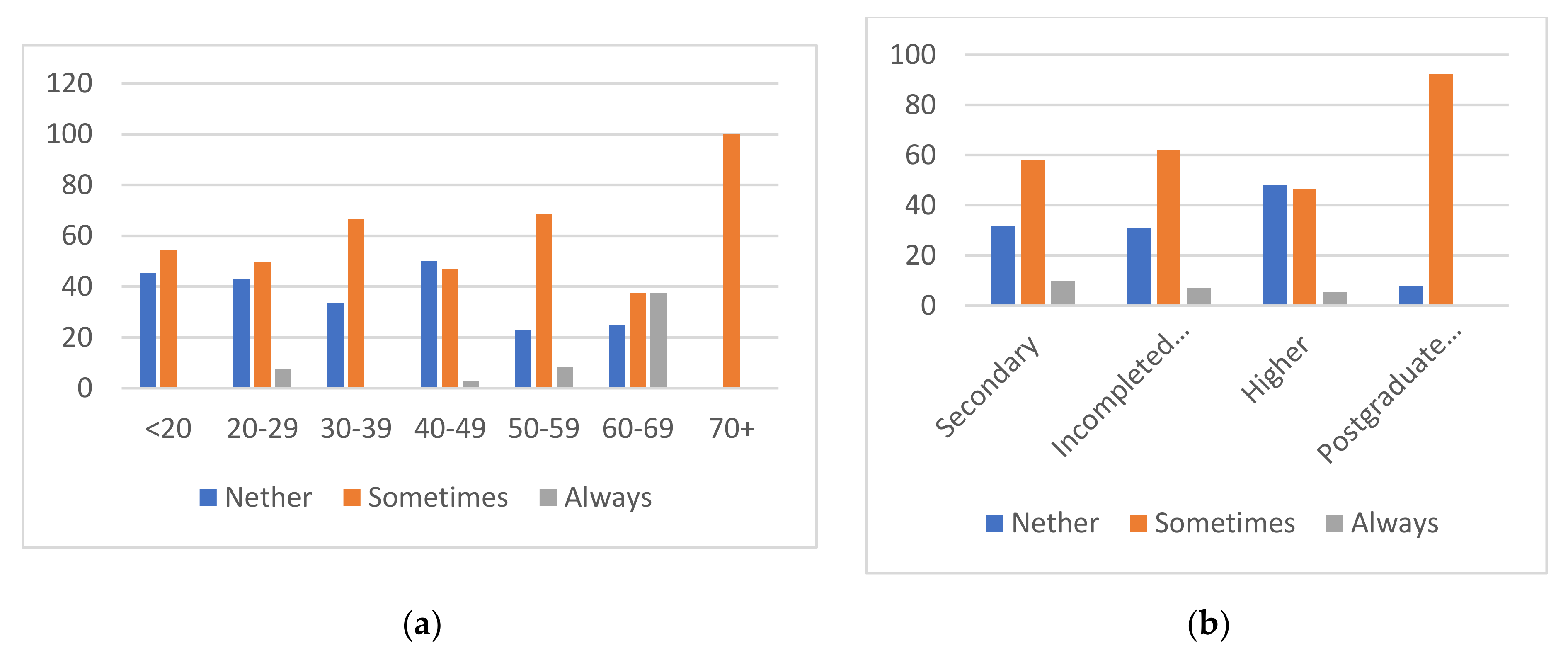

4.2. Demand-Side Study of Ecolabeled Goods in Russia (Results of the Survey)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Question | Answer | Code | Variable Name | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 1 | Gender | categorical |

| Female | 2 | |||

| Age | 16–19 | 1 | Age | rank |

| 20–29 | 2 | |||

| 30–39 | 3 | |||

| 40–49 | 4 | |||

| 50–59 | 5 | |||

| 60–69 | 5 | |||

| 70+ | 7 | |||

| Income | I actually live in poverty | 1 | Income | categorical |

| I save on necessary goods | 2 | |||

| I can satisfy all needs, but sometimes | ||||

| I have to save | 3 | |||

| I can satisfy all personal and family needs | 4 | |||

| I find it difficult to answer | 5 | |||

| I refuse to answer | 6 | |||

| Education | Secondary education | 1 | Education | rank |

| Incomplete higher education | 2 | |||

| Higher education | ||||

| (Bachelor’s degree or above) | 3 | |||

| Postgraduate education (postgraduate, doctoral, academic degree, degree MBA) | 4 | |||

| Region | Moscow region | 1 | Region | categorical |

| City with at least 1 mill inhabitants | 2 | |||

| Other Russian regions | 3 | |||

| What, in your opinion, is the main purpose of applying the ecolabel? | Correct (corresponds with ISO 14020) | 1 | Purpose | dichotomous |

| Wrong | 0 | |||

| What do you think is meant by ecological products? | Correct (corresponds with ISO 14020) | 1 | Eco_products | dichotomous |

| Wrong | 0 | |||

| What do you mean by environmental safety of products? | Correct (corresponds with ISO 14020) | 1 | En_saf | dichotomous |

| Wrong | 0 | |||

| Do you know what eco-labeling is? | Correct (corresponds with ISO 14020) | 1 | Ecolabel_SE | dichotomous |

| Wrong | 0 | |||

| Eco-labels are… | Correct (corresponds with ISO 14020) | 1 | Ecolabel_RE | dichotomous |

| Wrong | 0 | |||

| How many of these ecolabels are familiar to you? | 0,1,2,3,4,5 | 0,1,2,3,4,5 | Num_EL | numerical |

| Are you willing to pay a higher price for environmental products? | No | 0 | WTP | categorical |

| Yes | 1 | |||

| Difficult to answer | 2 | |||

| Do you check ecolabels on the packaging of a product before purchasing it? | No, nether | 1 | Checking_EL | categorical |

| Sometimes/Depending on the category of goods | 2 | |||

| Yes, always | 3 | |||

| What factors are more important for you when buying goods? | Choosing the answer “environmental safety” as one of the options | 1 | Factors | dichotomous |

| Not choosing answer “environmental safety” as one of the options | 0 |

References

- Horne, R.E. Limits to labels: The role of eco-labels in the assessment of product sustainability and routes to sustainable consumption. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, J.V.P.; Alfaro, J.A.; Mejia-Villa, A.; Ormazabal, M. ECO-labels as a multidimensional research topic: Trends and opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 806–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- François-Lecompte, A.; Bertrandias, L.; Bernard, Y. The environmental labelling rollout of consumer goods by public authorities: Analysis of and lessons learned from the French case. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratner, S.; Lazanyuk, I.; Revinova, S.; Gomonov, K. Barriers of consumer behavior for the development of the circular economy: Empirical evidence from Russia. Appl. Sci. 2020, 11, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Amstel, M.; Driessen, P.; Glasbergen, P. Eco-labeling and information asymmetry: A comparison of five eco-labels in the Netherlands. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochikashvili, M.; Bongaerts, J.C. How eco-labelling influences environmentally conscious consumption of construction products. Sustainability 2018, 10, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Zhang, W.; Wang, T.; Li, C.B.; Tao, L. Timely or considered? Brand trust repair strategies and mechanism after greenwashing in China—From a legitimacy perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 72, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konishi, Y. Efficiency properties of binary ecolabeling. Resour. Energy Econ. 2011, 33, 798–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnarowska, M.; Sołtysik, M.; Prusak, A. Impact of eco-labelling on the implementation of sustainable production and consumption. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2020, 86, 106505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hal, J.D.M. A labeling system as steppingstone for incentives related to the profitability of sustainable housing. Neth. J. Hous. Environ. Res. 2007, 22, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hetterich, J.; Bonnemeier, S.; Pritzke, M.; Georgiadis, A. Ecological sustainability—A customer requirement? Evidence from the automotive industry. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2012, 55, 1111–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, G. Information-based governance theory. In Handbook on Theories of Governance; Ansell, C., Torfing, J., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2016; pp. 281–292. [Google Scholar]

- Clemenz, G. Eco-labeling and horizontal product differentiation. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2009, 45, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markham, D.; Khare, A.; Beckman, T. Greenwashing: A proposal to restrict its spread. J. Environ. Assess. Policy Manag. 2014, 16, 1450030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, D.; Cao, C.; Huang, S. The influence of greenwashing perception on green purchasing intentions: The mediating role of green word-of-mouth and moderating role of green concern. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 740–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Bernard, S.; Rahman, I. Greenwashing in hotels: A structural model of trust and behavioral intentions. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 206, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zhang, W. Do government regulations prevent greenwashing? An evolutionary game analysis of heterogeneous enterprises. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 1489–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission (E.C.). Unfair Commercial Practices Directive. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/law-topic/consumers/unfair-commercial-practices-law/unfair-commercial-practices-directive_en (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Legislation.gov.au. Competition and Consumer Act 2010. 2021. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2018C00437 (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Business Insider. PepsiCo is Being Sued Over Its Naked Juice Marketing. 2021. Available online: https://www.businessinsider.com/pepsico-sued-for-naked-juice-marketing-2016-10 (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Zaharova, T.; Krakovetskaya, I. Eco-marketing: “Green” advertisement, assistance of the market and other tools to promote technological innovation in the university cities of the world and Russia. Vestn. Tomsk. Gos. Univ. Èkon. 2018, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, I. Ecolabeling, consumers’ preferences and taxation. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 2202–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman Group. Sustainability 2017 Report Overview and Highlights. 2017. Available online: http://store.hartman-group.com/content/Sustainability-2017-Overview.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Gutierrez, A.M.J.; Chiu, A.S.F.; Seva, R. A proposed framework on the affective design of eco-product labels. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, A.K.; Blomquist, G.C. Ecolabeled paper towels: Consumer valuation and expenditure analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Martino, J.; Nanere, M.G.; Dsouza, C. The effect of pro-environmental attitudes and eco-labelling information on green purchasing decisions in Australia. J. Nonprofit Public Sect. Mark. 2019, 31, 201–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tully, S.M.; Winer, R.S. The role of the beneficiary in willingness to pay for socially responsible products: A meta-analysis. J. Retail. 2014, 90, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Lim, Y.; Chang, P.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; Yu, X.; Lehto, M.R.; Cai, H. Ecolabel’s role in informing sustainable consumption: A naturalistic decision making study using eye tracking glasses. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 218, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G.; Hieke, S.; Wills, J. Sustainability labels on food products: Consumer motivation, understanding and use. Food Policy 2014, 44, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeone, M.; Scarpato, D.; Marinelli, N.; Simeone, M.; Scarpato, D.; Marinelli, N. Factors affecting food label complexity: Does the new EU regulation satisfy consumer issues? An exploratory study. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2016, 22, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, G.; Van Der Ven, H. The shadow of the consumer: Analyzing the importance of consumers to the uptake and sophistication of ratings, certifications, and eco-labels. Organ. Environ. 2018, 33, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnodar City Ranks First in the Russian Federation in Terms of the Provision of High-Quality Retail Space per Capita. 2021. Available online: https://realty.ria.ru/20150622/405526164.html (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kianpour, K. Importance of price for buying environmentally friendly products. J. Econ. Behav. Stud. 2012, 4, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Werf, H.M.; Salou, T. Economic value as a functional unit for environmental labelling of food and other consumer products. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 94, 394–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cui, Z.; Liang, X. Does it pay to be green? Financial benefits of environmental labeling among Chinese firms, 2000–2005. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2015, 11, 493–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, Y. Eco-labels and willingness-to-pay: A Hong Kong study. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2012, 1, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ISO 14024 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Number | Question | Answer |

| Q1 | Does the label provide information about the product lifecycle? | yes/no/partially/no information |

| Q2 | Are the environmental criteria for reporting the information selective? | yes/no/partially/no information |

| Q3 | Do the products meet the health and safety requirements and consumer needs (fitness for purpose)? | yes/no/partially/no information |

| Q4 | Is the environmental labeling program transparent in its information? | yes/no/partially/no information |

| Q5 | Does the product fit the product category, product environmental criteria and performance data set by the ecolabeling body? | yes/no/partially/no information |

| Q6 | Is there information that explains the meaning of the ecolabel? | yes/no/partially/no information |

| Q7 | Does the mark on the product match the official label of the environmental program? | yes/no/partially/no information |

| ISO 14021 | ||

| Q8 | Are the environmental claims used inappropriate claims such as: “environmentally sound; environmentally friendly; non-polluting; green”, etc.? | yes/no/partially/no information |

| Q9 | Are there explanations for the environmental statement if it is not clear? | yes/no/partially/no information |

| Q10 | Do the environmental claims comply with the special established requirements of 14021 chapter 5.7? | yes/no/partially/no information |

| Q11 | Are special signs used, for example: Mobius strip (recycling sign)? | yes/no/partially/no information |

| Part of the Questionnaire | Questions |

|---|---|

| Part I Sociodemographic data | Gender, age, place of living, education, income, occupation |

| Part II Recognition of ecolabels | Do you know what ecolabeling is? Ecolabels are… (choose the correct answer) How many types of ecolabels do you think there are? Are these ecolabels familiar to you? Which country do you think the below eco-label belongs to? Where do you know these ecolabels from? How many ecolabels do you think exist? What, in your opinion, is the main purpose of applying the ecolabel? Do you think that a unique gadget application for searching for information about ecolabeled products would be helpful? |

| Part III The factors of purchasing decision | Do you check ecolabels on the packaging of a product before purchasing it? (nether/sometimes, depending on the category of goods/ always) What factors are more important for you when buying goods? Do you think ecolabeled products are better (healthier, environment-friendly) than conventional ones? What do you think is meant by ecological products? What do you mean by the environmental safety of products? Are you willing to pay a higher price for environmental products? |

| Attributes | Value | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 67 | 26.8 |

| Female | 183 | 73.2 | |

| Age | 16–19 | 11 | 4.4 |

| 20–29 | 123 | 49.2 | |

| 30–39 | 36 | 14.4 | |

| 40–49 | 34 | 13.6 | |

| 50–59 | 35 | 14 | |

| 60–69 | 8 | 3.2 | |

| 70+ | 3 | 1.2 | |

| Income | I actually live in poverty | 5 | 2 |

| I save on necessary goods | 30 | 12 | |

| I can satisfy all needs, but sometimes I have to save | 168 | 67.2 | |

| I can satisfy all personal and family needs | 31 | 12.4 | |

| I find it difficult to answer | 11 | 4.4 | |

| I refuse to answer | 4 | 1.6 | |

| Education | Secondary education | 50 | 20 |

| Incomplete higher education | 58 | 23.2 | |

| Higher education (Bachelor’s degree or above) | 129 | 51.6 | |

| Postgraduate education (postgraduate, doctoral, academic degree, degree MBA) | 13 | 5.2 | |

| Region | Krasnodar and Krasnodar Region | 130 | 52 |

| Moscow and Moscow Region | 53 | 21.2 | |

| Volgograd | 12 | 4.8 | |

| Ufa | 3 | 1.2 | |

| Surgut | 3 | 1.2 | |

| Voronezh | 2 | 0.08 | |

| Kamchatka Krai | 37 | 14.8 | |

| Stavropol | 2 | 0.08 | |

| St. Petersburg | 4 | 1.6 | |

| Yaroslavl region | 2 | 0.08 | |

| Tula region | 2 | 0.08 |

| Requirement | Household Chemicals | Perfume and Hygiene | Food | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fully | Partially | Fully | Partially | Fully | Partially | |

| Q1 | 0.00 | 60.00 | 0.00 | 58.62 | 0.00 | 47.83 |

| Q2 | 93.33 | 3.33 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| Q3 | 50.00 | 43.33 | 58.62 | 0.00 | 30.43 | 0.00 |

| Q4 | 33.33 | 26.67 | 10.34 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Q5 | 0.00 | 93.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Q6 | 40.00 | 40.00 | 48.28 | 0.00 | 52.17 | 0.00 |

| Q7 | 36.67 | 0.00 | 20.69 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Q8 | 10.00 | 10.00 | 0.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 100.00 |

| Q9 | 46.67 | 40.00 | 55.17 | 13.79 | 52.17 | 30.43 |

| Q10 | 0.00 | 93.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Q11 | 76.67 | 10.00 | 93.10 | 6.90 | 56.52 | 30.43 |

| Question | Answer | Frequency | Percentage, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| What, in your opinion, is the main | Choosing the correct answer from the four variants suggested | 119 | 47.6 |

| purpose of applying the ecolabel? | |||

| What do you think is meant by | Choosing the correct answer from the four variants suggested | 99 | 39.6 |

| ecological products? | |||

| What do you mean by the | Choosing the correct answer from the four variants suggested | 121 | 48.4 |

| environmental safety of products? | |||

| Do you know what ecolabeling is? | Yes | 115 | 46 |

| No | 76 | 30.4 | |

| Find it difficult to answer | 59 | 23.6 | |

| Ecolabels are… | Choosing the correct answer from the four variants suggest-ed | 158 | 63.2 |

| How many of these ecolabels are | None | 146 | 58.4 |

| familiar to you? | One | 23 | 9.2 |

| Two | 21 | 8.4 | |

| Three | 13 | 5.2 | |

| Four | 0 | 0 | |

| All of them | 46 | 18.4 | |

| Do you think that a special gadget | Yes | 242 | 96.8 |

| application for searching information about ecolabeled products would be useful? | No | 2 | 0.8 |

| Find it difficult to answer | 6 | 2.4 | |

| Are you willing to pay a higher price for environmental products? | Yes | 99 | 39.6 |

| No | 79 | 31.6 | |

| Find it difficult to answer | 72 | 28.8 | |

| Do you check ecolabels on the packaging of a product before purchasing it? | Yes, always | 97 | 38.8 |

| No, nether | 16 | 6.4 | |

| Sometimes/Depending on the category of goods | 137 | 54.8 | |

| What factors are more important for you when buying goods? | Choosing the answer “environmental safety” as one of the options | 150 | 60 |

| Attribute | Answer | Pearson χ2 | p-Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Willingness-to-pay | 6.6422 | 0.03611 |

| Gender | Environmental safety as a factor of decision | 11.8295 | 0.00058 |

| Income | Willingness-to-pay | 52.5592 | 0.00001 |

| Education | Willingness-to-pay | 10.8395 | 0.09346 |

| Age | Frequency of checking ecolabels | 26.9521 | 0.00785 |

| Education | Frequency of checking ecolabels | 15.2568 | 0.01835 |

| Education | Knowing what ecolabeling is | 6.4784 | 0.09052 |

| Age | Knowing what ecolabeling is | 20.9118 | 0.00198 |

| Age | Environmental safety as a factor of decision | 21.6708 | 0.00139 |

| Place of living | Environmental safety as a factor of decision | 6.01570 | 0.04940 |

| Answer | Answer | Pearson χ2 | p-Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowing the purpose of ecolabeling | Willingness-to-pay | 6.2606 | 0.04371 |

| Environmental safety as a factor of decision | Willingness-to-pay | 7.6567 | 0.02175 |

| Willingness-to-pay | Frequency of checking eco-labels | 20.6275 | 0.00038 |

| Environmental safety as a factor of decision | Frequency of checking eco-labels | 13.5734 | 0.00113 |

| Knowing the purpose of ecolabeling | Knowing what ecolabeling is | 11.2832 | 0.0008 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ratner, S.; Gomonov, K.; Revinova, S.; Lazanyuk, I. Ecolabeling as a Policy Instrument for More Sustainable Development: The Evidence of Supply and Demand Interactions from Russia. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9581. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179581

Ratner S, Gomonov K, Revinova S, Lazanyuk I. Ecolabeling as a Policy Instrument for More Sustainable Development: The Evidence of Supply and Demand Interactions from Russia. Sustainability. 2021; 13(17):9581. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179581

Chicago/Turabian StyleRatner, Svetlana, Konstantin Gomonov, Svetlana Revinova, and Inna Lazanyuk. 2021. "Ecolabeling as a Policy Instrument for More Sustainable Development: The Evidence of Supply and Demand Interactions from Russia" Sustainability 13, no. 17: 9581. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179581

APA StyleRatner, S., Gomonov, K., Revinova, S., & Lazanyuk, I. (2021). Ecolabeling as a Policy Instrument for More Sustainable Development: The Evidence of Supply and Demand Interactions from Russia. Sustainability, 13(17), 9581. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179581