1. Introduction

Localism has been recognised as an alternative approach to sustainable development. Buddhist ecology [

1,

2,

3,

4] and Buddhist economics [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9] have been considered as the conceptual basis of this alternative approach. Buddhist ecology underscores that everything keeps changing and is connected to everything else. Buddhist economics is concerned with the attainment of human needs using minimum means, the production of local needs from local resources, and the conservation of non-renewable resources [

5]. By contrast, mainstream economics focuses on the maximisation of consumer satisfaction or financial returns.

Named after the author of the classic book

Small Is Beautiful, Schumacher College was founded in Totnes, Devon, England in 1991. Rob Hopkins and other committed permaculture teachers initiated the Transition Movement in Totnes in 2006 [

10,

11]. The transition process and model has since become widespread around the world. The movement has pursued a localised economy and has focused on retrofitting existing villages or towns into sustainable ones that rely on renewable energy sources rather than fossil fuels in the face of peak oil and global warming. Given the limited space available for putting in place new intentional communities, redeveloping and transforming existing communities has become a realistic and viable model through which to transit to a sustainable world [

12].

Like Totnes, Sannae District has been revitalised through community-driven initiatives since the late 1990s. Sannae District is located in Jeonbuk Province in the Republic of Korea (hereafter South Korea) with a population of about 2200 in 2019. Sannae District consists of several traditional, as opposed to intentional, small rural villages along a river flowing through a valley on the outskirts of Mt Jiri. Silsang-sa, an about 1200-year-old Zen Buddhist monastery, is situated in Sannae District. Like most other rural villages, Sannae District was on the verge of demographic desertification due to massive rural out-migration until the late 1990s. The Sannae villages have been revived first with an inflow of migrants and then diverse social and cultural activities and events developed and expanded by the migrants. These include the promotion of rural ecotourism, which in turn enhances the economic sustainability of the villages.

This paper traces and reconstructs the history of how Sannae District has been transformed into a sustainable rural community and seeks to understand the roles

Silsang-sa has played in revitalising Sannae District. The Buddhist philosophy that underlies the community rebuilding of Sannae District was illuminated in [

13]. The anecdotal community rebuilding activities led by

Silsang-sa were documented in [

14,

15]. Nonetheless, the existing rural development literature has scarcely focused on the application of Buddhist philosophy in the context of rural community reinvigoration. This research aims to yield conceptual and observational insights into how Buddhist ecological aspirations enabled community rebuilding in rural Korea.

This paper first outlines the data collection methods and then provides an overview of key concepts in Buddhism. This is followed by an introduction of Buddhist ecology and economics that represents the doctrines of ‘dependent arising’ and ‘Indra’s Net’. The paper then maps out the ramifications and consequences of various programs launched by Silsang-sa in Sannae District. The paper next reflects on the case study of Sannae District and briefly discusses the implications of the case study from the methodological point of view in the context of rural development.

2. Research Methods

This study is primarily based on the participant observation by the author. The author attended a one-week intensive seminary course entitled ‘Buddha’s Life and Enlightenment’ as part of the annual Winter School held in Silsang-sa in January 2020. The course was coordinated and taught by Reverend Tobŏp, a distinguished Buddhist monk at Silsang-sa who has pioneered the community rebuilding of Sannae District. The course introduced and discussed salient lessons from Buddhism, and drew critical implications for contemporary local and global societies. Because the course was residential, all the attendees in the course had the opportunity to stay in the temple. Prior to the seminary course in 2020, the author had participated in various community-rebuilding activities and events led by Silsang-sa in March 2016 and December 2018. These include working on Silsang-sa Farm with Indra’s Net Community members residing in Sannae District.

The study undertakes in-depth interviews as a supplementary data collection method. In December 2018, the author interviewed six residents from the community regarding the rebuilding history of Sannae District. The participants had all lived in the district for more than 20 years. The interviewees comprised of three natives and three migrants. They were asked to identify their experience and observations of the rural landscape changes in Sannae District over the past two decades in terms of food production, human settlement, community cohesion, and the local economy.

3. Key Concepts in Buddhism

Buddhism refers to the religious, philosophical, and social movement that stems from the Buddha’s teaching. The word ‘Buddha’ stemmed from a Sanskrit verbal root ‘

budh’. The primary meaning of the verb ‘

budh’ is ‘to awaken or wake up’. Hence, the word ‘

buddha’, the particle derived from ‘

budh’, is translated as ‘the awakened’. The proper noun ‘Buddha’ refers to the historical person Siddhārtha Gautama who attained his enlightenment. The very central theme in Buddha’s teaching lies in ‘dependent arising (or dependent origination)’ (

pratītyasamutpāda), which states that every being (thing, phenomenon, or act) arises in dependence upon other beings [

16].

The doctrine of ‘dependent arising’ entails that of ‘not-self’ (

anātman). The doctrine of ‘not-self’ explains that nothing can exist by itself, and that there is no such ‘self’ (

ātman) that is unchanging, everlasting, and independent. The word

anātman can also be translated into ‘non-self’ [

17,

18,

19,

20], or ‘no-self (or selflessness)’ [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Given that the prefix ‘

an’ in

anātman literally means ‘not’ in English, however, ‘not-self’ [

25] would be the most appropriate English translation for the word

anātman.

In Buddhism, it is said that belief in the existence of the independent, unchanging, everlasting ‘self’ causes ‘suffering’ (

duḥkha). Suffering does not refer to physical or psychological pain, but points to a mental state where there is a fundamental disparity between what things really are and what they are perceived to be [

24]. In other words, suffering occurs when one believes that what they perceive is what the reality is. In the Buddhist tradition, therefore, the antonym of the word ‘suffering’ (

duḥkha) is ‘cessation’ (

nirvāṇa) and not ‘pleasure or happiness’ [

23]. Buddhism preaches that one’s ‘suffering’ or ‘disease of mind’ arises because of the delusion (

moha) that their permanent ‘self’ exists [

26,

27,

28,

29].

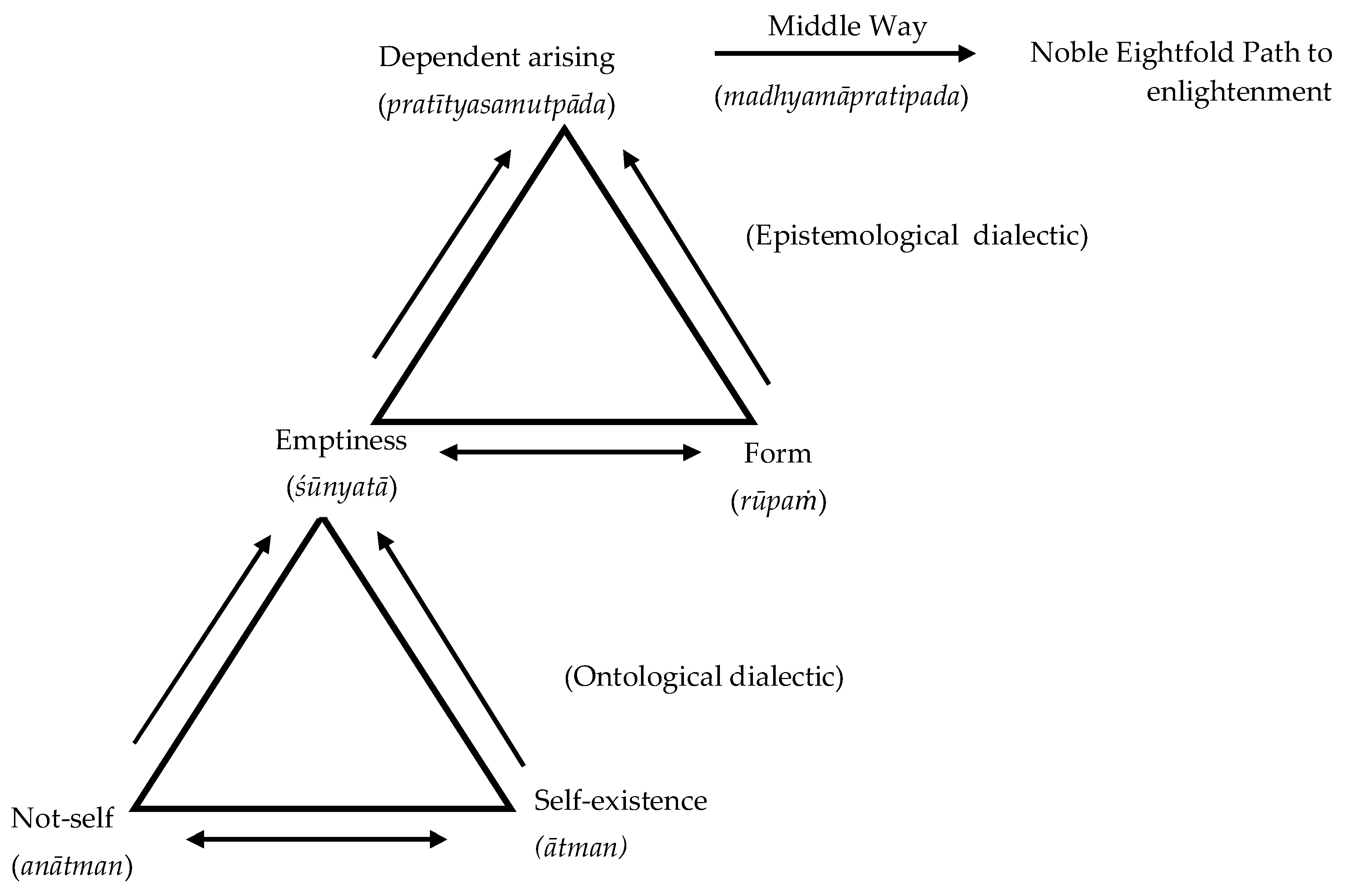

Buddhism objects to the ontological dichotomy of self-existence and not-self. Buddhism asserts that there is no everlasting self, but does not deny the existence of an individual self [

20,

25,

26]. In other words, Buddhists deny that there is an eternal reality underlying the sense of ‘self’, but do not deny that the self, albeit as an impermanent entity, exists. The dialectical negation of the two gives birth to the doctrine of emptiness (

śūnyatā), which means that any being is devoid of an unchanging ‘self’ and there does not exist such a being that is not empty of a ‘self’. The Sanskrit word

śūnyatā refers to something that ‘looks swollen from the outside but is hollow inside’ and connotes the concept of ‘zero’ [

30] (p. 15). Like the word

śūnyatā, the number ‘zero’ conveys the meaning of ‘non-existence’, but exists as an indispensable number.

From the epistemological point of view, the concept ‘emptiness’ can hardly be defined without the concept of ‘form’. The relative dependence of the two concepts is succinctly depicted in the

Heart Sutra (

Prajñāpāramitā Hṛdaya Sūtra): Form is emptiness, and emptiness is form (

rūpaṁ śūnyatā, śūnyataiva rūpaṁ); The same holds true of feelings, perceptions, phenomena, and consciousness [

31]. The dialectical negation of ‘emptiness’ and ‘form’ brings the philosophical discussion back to the core of Buddha’s teaching, ‘dependent arising’, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

The Buddha preached the ‘Middle Way’ (

madhyamāpratipada) principle upon which people can make decisions of what is right or wrong in everyday life. The word ‘

madhya’ literally means ‘unbiased’ or ‘in the middle that rejects two extremes’. In Buddhism, the ‘Middle Way’ refers to the way to freedom (

nirodha) from suffering (

duḥkha) caused by the misconception of self-existence [

18,

32]. The Buddha taught practising the ‘Noble Eightfold Path’ (

āryāṣṭāṅgamārga)—the way to liberation from suffering or towards living with peace of mind: that is, right view, right thought, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration [

33,

34].

4. Buddhist Ecology and Economics: Indra’s Net

The ‘Noble Eightfold Path’ doctrine states that ‘right view’ spawns ‘right thought’ and ‘right action’. ‘Right view’ refers to the clear and unbiased understanding of ‘dependent arising’ amongst all beings in the world. The doctrine of ‘dependent arising’ in Buddhism is often described by Indra’s Net (

indrajala), which originated from the Hindu mythology where Deva Indra uses a vast net of jewels as a protective weapon hanging over his palace [

35]. In the mythological Indra’s Net, every jewel reflects all others, and all jewels are reflected in any single jewel.

The

Flower Ornament Scripture or the

Mahāvaipulya Buddhāvataṃsaka Sūtra (

Avataṃsaka Sutra in short) adopted the metaphor Indra’s Net because it symbolises well the Mahāyāna Buddhist view of how the universe is interconnected within. Each jewel at the intersections of the net represents an entity or a phenomenon, and exists only in their mutual dependence on all others [

36]. In Mahāyāna Buddhism, the universe is seen as a net of interconnection and interdependency among all beings, in which every being is present in the whole universe, and the whole universe is present in every being. Hence, every being is devoid of ‘self-existence’ [

2,

3,

35,

37,

38].

The

Avataṃsaka Sutra was translated from Sanskrit into Chinese in the 5th to 7th century, and the logic of Indra’s Net further developed into

Hua-yen Buddhism in China, Korea, and Japan [

35,

39]. In

Hua-yen Buddhism, the historical Buddha is not the only enlightened. Any

bodhisattva (anyone who seeks achieving enlightenment for the welfare of all beings) can become a buddha. Buddhas are those who ‘know [that] all phenomena come from dependent origination [and] know [that] all the different phenomena in all worlds [are] interrelated in Indra’s Net’ [

40] (p. 925). Chapter 40 of the

Avataṃsaka Sutra clarifies that every being in the world contains Buddha-nature (

buddha-dhātu):

- With as many buddhas as atoms in all lands

- I bow to all buddhas,

- With a mind directed to all buddhas,

- By the power of the vow of the practice of good

- In a single atom, buddhas as many as atoms

- Sit in the midst of enlightening beings;

- So it is of all things in the cosmos—

- I realize all are filled with buddhas.

Buddhist ecology can be derived from the doctrine of Indra’s Net [

29,

41,

42]. Thich Nhat Hanh [

17] demystified Buddhist ecology simply by taking the life of a flower as an example: A flower cannot grow without non-flower elements including clouds, soil, and sunshine. Neither can human beings survive without nature. Buddhist ecology is not just concerned with the interrelationship between living organisms and their habitats, but extends the boundary of concern to all creatures in the cosmos [

43]. Deeply embedded in Buddhist ecology is the thought that all beings should be respected because any being could potentially become a buddha. Chapter 3 of the

Diamond Sutra (

Vajracchedikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra) reads, as follows:

Then the Buddha said to Subhuti, ‘The bodhisattvas, the mahàsattvas, should train their minds to think in this way. All living creatures, whether born from eggs or from the womb, whether produced from moisture or from transformation, whether they have form or are without form, whether they have thought, are without thought, or are neither with or without thought—all these I will cause to pass over into the extinction of the nirvana of no remainder.

The general direction of Buddhist economics points to the ‘right livelihood’ component of the Noble Eightfold Path [

5]. ‘Right view’ and ‘right action’ are to Buddhist ecology what ‘right livelihood’ is to Buddhist economics. What the right livelihood should look like can be deduced from Buddhist ecology. The metaphor of Indra’s Net manifests that human beings are part of nature and can never be free of it: To harm the natural environment is to harm human beings, and to harm humans is to harm non-humans. Schumacher [

5] argued that over-consumption is an act of violence against nature because most products humans consume are originally from nature, and that the materialistic production and consumption of goods and services should be set at a bare minimum. The excessive exploitation of non-renewable natural resources eventually deprives future generations’ benefitting from using them [

5,

17]. The growth-oriented economic system has globally over-exploited natural resources and caused environmental pollution, putting future economic growth in jeopardy [

45,

46,

47,

48]. In this light, Buddhist economics promotes transitioning to a regenerative economy where material and energy resources are recycled, and a circular society where wealth, technology and knowledge are also circulated in a sustainable loop [

49]. In the same way, Norberg-Hodge [

9] put forward that a decentralised economy relying on local food and energy is the pathway to making the world sustainable and to fixing the problems caused by the inhumane global economic system.

5. Buddhist-Led Community Rebuilding from the Indra’s Net Perspective: A Case Study of Sannae District in South Korea

This section traces 20 years of village-making efforts and actions taken to revive Sannae District in South Korea. The section first introduces the Indra’s Net Community movement led by Reverend Tobŏp since the 1990s, then conceptualises his diagnostic thoughts given to the plight of rural decline in South Korea, and next briefly maps out the various initiative actions into an Indra’s Net.

5.1. Reverend Tobŏp and the Indra’s Net Life Community Movement

Despite the teaching of profound ecological economics, Buddhism is often mistakenly considered as being indifferent to worldly concerns such as environmental pollution and social conflicts. On the contrary, contemporary Buddhism has planted seeds for grassroots social movements dedicated to building sustainable communities. Examples of Buddhist-led community building movements include the ‘Asoke Community’ movement in Thailand and the ‘Indra’s Net Life Community’ movement in South Korea.

The Asoke Community movement emerged in the 1970s in criticism of the Thai mainstream Buddhist community, and evolved into establishing its own Buddhist group. In an Asoke community, Buddhist monks and laypersons are living together up to the standard of Buddhist ecology and economics [

50]. The Asoke Buddhist group supported the original teachings of the Buddha including the Noble Eightfold Path and neglected the worship of Buddha images [

8].

Like the Asoke Community movement, Indra’s Net Life Community movement accentuates mindful pacifist living that respects all creatures on the Earth. Unlike the Asoke group, Indra’s Net Life Community is not a Buddhist group diverged and separated from the mainstream Buddhist sects in South Korea. Moreover, the Indra’s Net Life Community movement focuses on rejuvenating and transforming existing communities whereas the Asoke community movement has created intentional communities.

The Indra’s Net Life Community movement takes the self-help development approach and pursues the holistic sustainability of rural communities as in other Buddhism-based rural development movements. These include the

Sarvodaya Shramadana movement that promotes resource sharing within and between villages in Sri Lanka [

51,

52,

53], the Ladakh Project in India to protect local culture and ecological indigenous lifestyle [

26], Sufficiency Economy for marginal regions in Thailand [

8,

54], and the use of the Gross National Happiness index for sustainable development in Bhutan [

55,

56]. Compared to Sufficiency Economy or Gross National Happiness, the Indra’s Net Life Community movement pursues bottom-up community-driven rural development. In contrast to

Sarvodaya Shramadana, the Indra’s Net Life Community movement has yet to spread nationwide. Unlike the Ladakh Project, the Indra’s Net Life Community movement has been led by a local Buddhist monk.

Reverend Tobŏp has led the Indra’s Net Life Community movement to bring local communities in South Korea away from individualistic neoliberal structures. He reiterates that people should live a simple and non-violent life, a keynote of Buddhist economics as described in Schumacher [

5]. He understands and interprets community sustainability issues from the Indra’s Net perspective, and sees humans as social beings and society as an organic entity. He underlines the interdependent relationship between humans and the natural environment, and between agriculture and other industries. Reverend Tobŏp’s conception of organic rural community developed to form a non-governmental organisation named ‘Indra’s Net Life Community’ in 1999 [

14,

15].

The monk’s idea of community rebuilding was inspired by Gandhi’s [

57] vision that the making of self-governing villages is a pathway to an independent nation and there is no sustainable nation without sustainable villages. Tobŏp [

58] argued that an individual human being belongs to a family, which belongs to a village, which belongs to a nation and its ecosystem, which belongs to the globe. His thought as to what a rural village should look like went beyond the autonomy of villages. Reverend Tobŏp stated in the seminary course in January 2020:

I agree with Gandhi who stressed a village community needs to grow its own capacity of autonomous self-perpetuating governance. Certainly, there is no nation without villages. More importantly, however, a rural village consists of nature and humans. As per Buddha’s teaching, humans can exist only in relation to nature. Humans and the natural environment are interdependent.

Reverend Tobŏp maintains that self-sustained rural development is crucial for sustainable national development. He argues that sustainability is not a choice but a necessity for rural development because a village is a place for families to live in together generation to generation and not a business enterprise to grow. He insists that a sustainable village should not suffer from poverty, but should not crave for materialistic prosperity, either. From his observations of Sannae District, he postulated that economic growth alone would eventually bring a village into a socially and environmentally unsustainable state [

59].

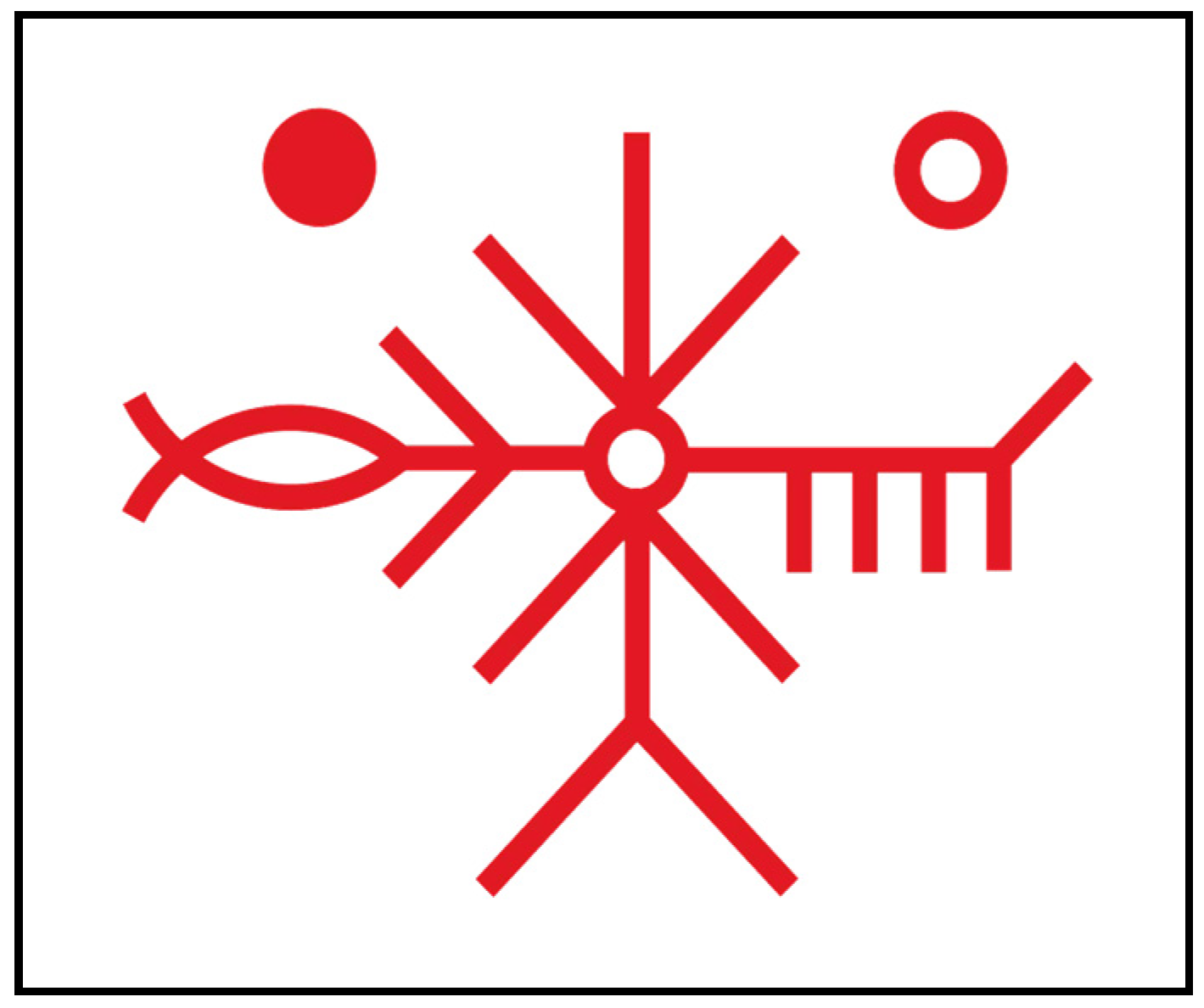

The Indra’s Net philosophy is well reflected in the logo of ‘Indra’s Net Life Community’ as presented in

Figure 2, which symbolises the worldview that underlies the movement. The logo consists of the pictographic symbols of the universe: humans, trees, fish, and animals. The logo recognises that everything under the sun and the moon are all intertwined. Emphasis is placed on the interconnectedness of humans and non-humans. Contemporary environmental problems are seen to have originated from the collective ignorance of the dependent arising of human-induced pollution, environmental degradation, and the consequent impacts on humans themselves and other living creatures.

The Buddhist doctrine of dependent arising and the Indra’s Net philosophy advocates communitarianism. According to

Merriam-Webster English Dictionary, the word ‘community’ is rooted in the Latin

communis. The prefix ‘

com-’ refers to ‘together’ or ‘along with’. In Latin, the word

munis originates from the verb

munire which means ‘to fortify’ or ‘to defend’. Thus, it can be said that a communitarian society shares a strong sense of mutual help, and cherishes common values [

60]. Communitarianism should not be equated with communism. Communism seeks the equal distribution of wealth and denies the private property rights regime. By contrast, communitarians believe in the inherent character of humans to cooperate and their ability to achieve what they can achieve through cooperation. The faith goes beyond the family and relatives and emphasises that all individual humans and their families are interconnected as a part of the whole universe.

5.2. Reverend Tobŏp’s Diagnostic Thoughts on Rural Sustainability

Due to the growing urban industries, Korea’s agriculture has undergone tidal rural out-migration since the 1960s. The South Korean rural population share decreased from 72.3% in 1960 to 26.2% in 1990 and further to 18.6% in 2019 [

61]. Along with mechanisation, monoculture, and food production heavily relies on the use of pesticides, herbicides, and artificial fertilizers. Agricultural industrialisation has resulted in environmental degradation, and led to the disappearance of traditional labour-sharing cooperatives. With increased economic affluence, individualistic values have replaced communitarian ones in rural Korea [

62].

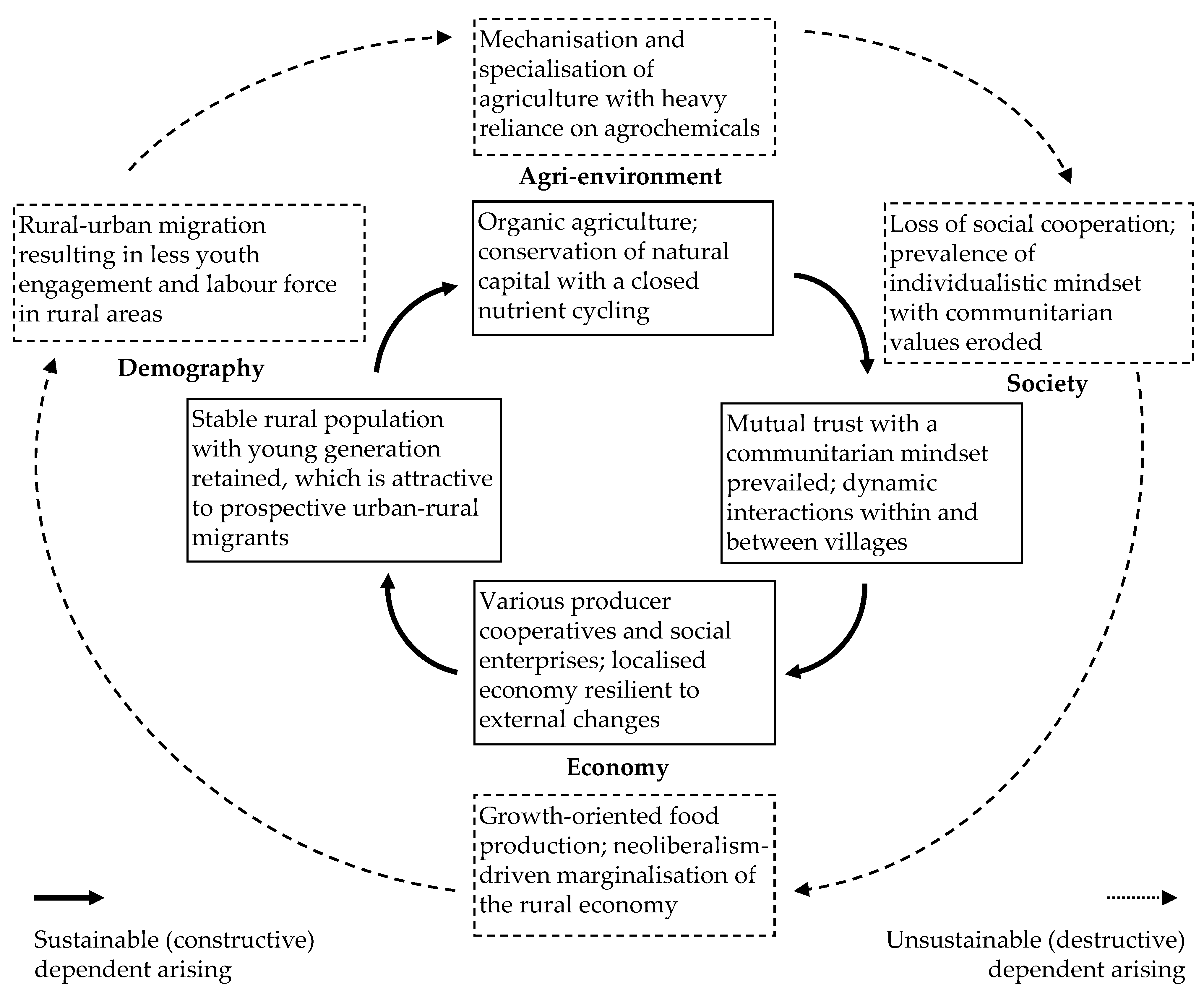

Reverend Tobŏp came to the view that the unsustainability of Korean rural villages occurred due to the dependent arising of massive rural-urban migration, a lack of labour force in rural areas, heavy reliance on agrochemicals and land degradation, eroded social cohesion, and fewer income-generating opportunities. The out-migration of rural people would continue as long as they consider that their hometown is unsustainable. The dotted lines in

Figure 3 indicate the exacerbating cycle of events that have arisen in many rural communities in South Korea since the 1960s. In fact, any country is subject to following an unsustainable rural development path. Norberg-Hodge [

26] (p. 147) wrote that ‘throughout the world, the process of development has displaced and marginalised self-reliant local economies in general…Now the same process is occurring in the Third World, only much more rapidly, as rural subsistence is steadily eroded’.

Figure 3 also delineates the virtuous co-arising of rural in-migration, organic farming, communitarian cooperation, and a localised economy. From this notional constructive loop, two remedial initiatives can be prescribed for reviving the declining rural communities. First, the in-migration of young generations is imperative to rejuvenate aging rural communities. Any place-based community can disappear when it lacks young generations. Reverend Tobŏp, however, stressed that migrants do not have to be farmers because agricultural villages also need bakers, carpenters, bicycle mechanics, school teachers, and so on. Second, the would-be migrant farmers should have the right thought that agriculture is not just a functional subset of the industrial economy, but the basis of the whole economy as well as of rural communities. Equally important, the migrants should be willing to practise organic farming. In line with the Indra’s Net worldview, Reverend Tobŏp believes that organic farming can stimulate community cooperation and solidarity, which is integral to the social reinvigoration of rural communities.

5.3. A Net of Interwoven Initiatives and Actions Taken to Reinvigorate Sannae District

A chain of initiatives and actions have occurred one after another in the rebuilding process of the Sannae villages since the late 1990s.

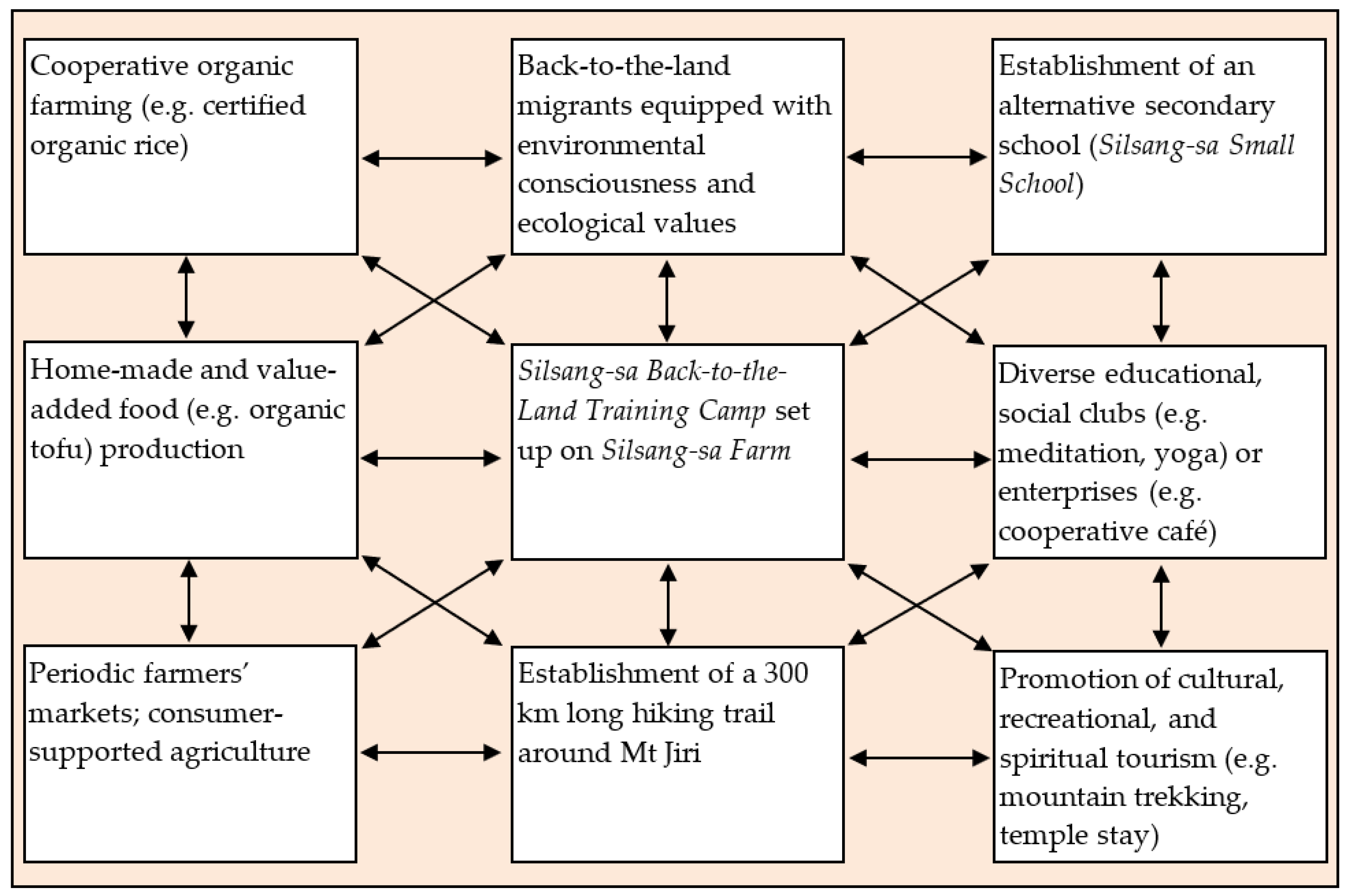

Figure 4 portrays the connectivity of the initial actions and activities taken to revive the villages. First of all, in 1998 Reverend Tobŏp launched an agricultural training program for the back-to-the-land migrant hopefuls who did not have farming experience, making use of 10 ha of agricultural land (named

Silsang-sa Farm) that belongs to the monastery [

13].

Silsang-sa Back-to-the-Land Training Camp offered three-month long courses twice a year (in spring and autumn). The training program focused on the on-site practices of agricultural techniques with emphasis on organic farming as well as Buddhist ecology [

59]. The training program was set up with the view that farming migrants with a strong interest in ecologically sustainable farming would play a pivotal role not only in refilling the demographic vacuum of Sannae District but also in enhancing rural sustainability in the environmental dimension.

About 100 out of the trainees who completed the back-to-the-land training program permanently migrated to Sannae District while a few hundred other trainees chose to settle in other rural districts in South Korea (an anonymous migrant farmer, personal conversation, 2018). Most of the migrant farmers who settled in Sannae District were characterised by environmental stewardship attitudes and a post-productivist mindset, partly owing to the Buddhism-based agricultural training program, and partly because of their urban experience of environmental pollution caused by the growth-oriented economy [

13,

63]. The success-failure migration theory in which return migration is considered a ‘failure’ [

64,

65] is not applicable to the rural migrants in Sannae District. They have pioneered the setting up of place-based farmers’ cooperatives in pursuit of organic food production, which is distributed through periodic farmers’ markets and the consumer-supported agriculture scheme. Their organic farming and marketing activities have helped make the district economically viable.

The overwhelming majority of the migrants to Sannae District were also found to have tertiary educational qualifications [

63], and were concerned about the education of their children. They wished to send their children to a school where the students are liberated from competition and exams and guided to be engaged in what they like to learn as well as the usual subjects. In response to this demand, an alternative secondary school named

Silsang-sa Small School was established in 2001. The school has had a vital role in retaining the youth and inducing even more families to consider migrating to Sannae District [

59].

Owing to continuing in-migration, the migrant families in Sannae accounted for about 25% of the total population of the district as of 2018 (an anonymous migrant farmer, personal conversation, 2018). As a result, the socio-economic characteristics of the migrant families have diversified. They included school teachers, carpenters, and food service providers. The overall population of Sannae District has remained around 2200 since the late 1990s while many other rural districts have witnessed a continuous decline in the number of inhabitants [

66].

The in-migrants have a strong desire and demand for cultural activities and services, which gave rise to a variety of cultural clubs including a writers’ club and even a philosophical discussion group (an anonymous migrant, personal conversation, 2018). The migrant farmers in Sannae District endeavoured to blend into the host community by interacting with them through social clubs. For example, a folklore club regularly invites local residents to their musical performances which are held in a small theatre in Sannae District. A kitchen renovation club, which was formed by a group of migrants, offers their home improvement skills to the native elderly living in run-down houses [

63].

Many in-migrants and natives in the villages shared their knowledge, skills, and resources in constructing a village café Todak in 2012. The café operates as a social cooperative. All the operating profits are used for community rebuilding activities and programs in Sannae District. The café has since become a cultural focal point of the Sannae community. An anonymous migrant farmer who was interviewed in 2018 commented on the multifunctionality of the café and other venues in the Sannae community, as follows:

The café Todak is a library for children out of school hours. The gardens in Silsang-sa are a playground for preschool children. Silsang-sa Farm has been an agricultural education centre for the students at Silsang-sa Small School. Across the nation, primary and secondary school education is set for the sake of being prepared for college entrance exams. This is a chronic problem associated with the current school education system. In Sannae District, the whole community is a virtual alternative school for our children.

Another landmark rural development initiative involved connecting a number of previously fragmented walking trails around Mt Jiri National Park in South Korea. Reverend Tobŏp proposed this idea and led the government-community partnership project in 2008. The circular hiking trail of about 300 km eventually connects more than about 100 mountainous rural villages including Sannae District [

59,

67]. The newly established hiking trail has attracted numerous mountain trekkers around the year. As the number of hiking travellers increased, the demand for temporary accommodation also increased. This phenomenon provided native farming households with a new business opportunity for off-farm income generation by running guesthouses.

The abovementioned initiatives should not be treated as separate one-off events. Rather, one initiative has led to another and they have been interwoven in the end.

Silsang-sa Back-to-the-Land Training Camp brought media attention nationwide because it was the first ever social work of its kind in South Korea. Many local governments have since set up new back-to-the land agricultural training camps across the country. The local government of Namwon County recognised the efforts of

Silsang-sa for training back-to-the-land migrant hopefuls and started supporting the

Silsang-sa program with financial aid. The financial support was aimed at attracting more migrants into Namwon District. Most rural counties in South Korea have been desperate to lure more migrants into their counties to maintain their demographic sustainability. In 2011, the agricultural training camp and program at

Silsang-sa were moved to and operated by another Buddhist monastery located in Namwon County, Jeonbuk Province [

59]. The agricultural produce from

Silsang-sa Farm is sold via a local community-supported agriculture scheme. A portion of

Silsang-sa Farm has now been leased to some of the migrant farmers who settled in Sannae District.

6. Reflections on the Case Study on Sustainable Rural Development

Several notes should be made to the net of initiatives and actions delineated in

Figure 4. First, the chain of actions and activities developed naturally, but there was no masterplan or blueprint of how to construct the Indra’s Net at the community level. Reverend Tobŏp triggered the community revival process, but the transformative revitalisation of Sannae District would not have been possible without the collective efforts of all of the community members [

13]. Second, the action and event cells in

Figure 4 are never meant to be exhaustive. The omitted yet important elements of the Sannae community net in

Figure 4 include youth engagement activities and programs, lay Buddhist activities, and the presence of a second-hand goods exchange shop. Third, Sannae District is neither a self-sufficient island nor an isolated society. Rather, the villages are connected to a wider community through consumer-supported agriculture, agri-tourism, and nature-based tourism. Fourth, it is utterly important to attain and retain the connectivity of the existing knots of the Sannae community because these knots may keep changing over time. For example, an anonymous native farmer interviewed in 2018 was concerned that the land price in Sannae District had increased due to the increasing number of migrants. This remark indicates that the villages can become attractive to retirees who can afford to purchase the land, rather than younger generations. Thus, it is possible for Sannae District to turn into a set of rural retirement villages.

Finally, the doctrine of Indra’s Net can provide a conceptual framework but not a device with which to quantitatively measure the magnitude of sustainability in a separate dimension. In the Indra’s Net framework, it matters whether the activities and initiatives within each of the sustainability dimensions have come into being in an interdependent manner. Measuring sustainability quantitatively would undermine the reality that the social, economic, and environmental drivers and indicators of sustainability are interconnected. The connotation of sustainable development is often graphically expressed by the three-fold overlap of circles or a continuous triangular field representing the economic, environmental, and social sustainability dimensions [

68]. Mapping sustainable development with a Venn diagram or a triangle does not adequately capture the interconnectedness of the sustainability dimensions. For instance, the sustainability set diagrams discussed in [

68] can help define the common elements that are included in all of the three dimensions and can inform what needs to be done to accomplish economic, environmental, and social sustainability simultaneously. However, this sustainability concept assumes that a certain level of compromise of each of the dimensions is inevitable. In fact, a strategically defined array of sustainability indicators is often employed to balance economic, environmental, and social concerns because it is not possible to accomplish the maximum achievable level of sustainability in all dimensions simultaneously [

69,

70].

To some extent, the Buddhist perspective of community rebuilding is in parallel with that of rural web analysis. In the rural web analysis techniques, the development of a rural village can be mapped out with six interconnected dimensions [

71,

72]: A rural village can be developed when it mobilises local resources (

endogeneity), produces value-added products (

novelty production) with the capacity of institutions to control, strengthen existing markets or construct new markets (

the governance of markets), and generates activities and initiatives (

institutional arrangements) that enhance cooperation (

social capital) among actors at the local and regional level, maintaining the ecological conditions necessary for human well-being (

sustainability). Like Indra’s Net, the rural web analysis premises that rural development is equivalent to a synergistic flow from one dimension to another, and that a rural village needs to be connected to a broader community through local markets and institutions.

Table 1 juxtaposes the features of the conventional sustainability matrix, rural web analysis, and Indra’s Net in terms of their approaches to sustainability assessment. A sustainability matrix tends to allow a compromise between sustainability dimensions. A conceptual pitfall of the rural web analysis lies in the proposition that the existence of ecological sustainability is subject to human well-being. On the contrary, sustainability is the ultimate goal of rural development in the Indra’s Net perspective. Moreover, the rural web analysis focuses on functional economic and social sustainability, and does not provide a clear account as to how to achieve ecological sustainability. The Indra’s Net perspective strongly takes the position that economic growth should not compromise environmental quality and social integrity.

7. Conclusions

The Indra’s Net worldview calls for a paradigm shift to ecological holism from the dichotomous view that splits humanity and nature. From the Indra’s Net perspective, the primary dimensions of sustainability are all equally important. It is not possible to achieve ecological sustainability without social and economic sustainability, and not possible to achieve social and economic sustainability without ecological sustainability.

The case study of Sannae District in South Korea demonstrates that the Indra’s Net philosophy can offer a realistic pathway to sustainable rural redevelopment. The case study implies that there should be the right viewpoint followed by the right thought, and the right action in revitalising rural communities at risk. The community rebuilding of Sannae villages started with the right understanding of the ‘dependent arising’ doctrine accompanied by the right actions to remedy the demographic, environmental, and economic pitfalls of the community. This study has found that the agricultural training program acted as a key initiator in pulling back-to-the-land migrants who had strong desire and demand for a cultural life and healthy food into Sannae District. Consequently, various cultural social clubs (e.g., meditation and yoga clubs) and small-scale organic food processing businesses have blossomed in the rural district. Thanks to the high uptake of organic agriculture, the presence of the historic Buddhist monastery, and the circular Mt Jiri hiking trail, Sannae District has continuously attracted adventurous green tourists. An influx of tourists has provided local residents with business opportunities to meet tourist demand for accommodation and food services. Diverse and vibrant village livelihoods have in turn lured additional urban–rural migration.

Silsang-sa has been the driver of the transition process in Sannae District just as Schumacher College has been conducive to the transition movement in Totnes. Silsang-sa has been the mastermind of the redevelopment and transformation of the villages. Silsang-sa has been the educational centre for Buddhist ecology and economics, and has facilitated various programs and events for the sustainable development of Sannae District.

This article does not claim that Sannae District offers a universal model of rural community rebuilding that is applicable to any rural village. Internal and external situations faced by rural villages vary village to village and keep changing interdependently. Filling in the demographic vacuum was the top priority for Sannae District in the 1990s although the villages have recently looked for transition to energy-saving human settlements. The case study implies that it would take a long time to rejuvenate a rural community once any part of the community net is broken down. Thus, continuous and collective efforts for synergising all the forces and actions are required for a rural community to stay sustainable.