1. Introduction

Complementary currencies (community alternative; in Poland called “local”) are not a new phenomenon cf. [

1]. They have accompanied communities for probably thousands of years, yet a systematic increase in interest in complementary currencies around the world, mainly in Europe, the Americas, Australia and Oceania and Japan, has been observed since the 1980s. Blanc and Fare [

2] (pp. 299–300) report that the greatest increase in interest and emergence of complementary currencies occurred in 2002, while this expansion was associated not so much with the proliferation (replication) of a single system of complementary currencies in different parts of the world, but with its horizontal and vertical diversification cf. [

3] (p. 64), on the one hand, taking the form of innovation, covering a wide spectrum of different models of complementary currencies, and on the other hand, taking the form of experiment within the monetary systems of different countries. Complementary currencies exist around the world, and many countries have more than one complementary currency.

Complementary currencies are not money. They are referred to as quasi-money because they perform the function of money in certain communities and are created by groups of citizens, companies, associations and private capital firms (i.e., local private initiatives in various formats) and are complementary to national currencies in circulation. They are also not an alternative to the conventional monetary system.

Complementary currency systems provide new tools that can function alongside official currencies without replacing them [

4] (p. 72). They are means of transaction and settlement, complementing the payment system based on money issued by central banks, but also a type of social contract. They occur in a geographically limited area (e.g., within the country, province, city, municipality) and they take a material form or occur in a dematerialized form in the form of virtual money as an IT record.

Available information on the actual number of complementary currencies in the world is questionable due to the fact that many of them have not been made public or examined. In addition, the systems of complementary currencies in the world are diverse, among other things, due to the political and ideological basis present in different countries, more or less connected to the official monetary system in the country, or integration with local political and economic institutions cf. [

5] (pp. 848–849). According to statistics, in 1990, there were about 100 complementary currencies in the world [

6]; in 2016, there were already about 6000 [

7] (p. 5) [

8] (p. 2), and a similar number was reported in 2021. It is characteristic that local currencies function primarily in economically highly developed countries. Their high growth rate in the world is the result of:

The use of a standardized model in which the unit of account is introduced (1 unit of the complementary currency = 1 unit of the national currency), which means the absence of exchange rates and spreads in the complementary currencies (so-called rigid link, in other words, a rigid exchange rate in relation to the national currency, although many complementary currencies are not actually convertible), although if the national currency subjects to inflation, then the same level of inflation will apply to the complementary currency (under mismanagement, inflation can be induced inside the system of complementary currencies. These are errors that lie with the system administrator and can be corrected by him or her);

Not omitting in commercial transactions and operations the commonly binding currency (among others because of the necessity to use it, e.g., in tax settlements);

The lack of possibility to sell complementary currencies because their idea is to maintain a sufficient amount of a transaction medium (complementary acting alongside the state) in the community that uses this currency;

Defining the security framework for participants, additional responsibilities and specific regulations for system administrators of complementary currencies (a system administrator is able to determine whether the system has been broken into, whether there has been a theft, who has broken in, to whose account complementary currencies have been transferred, etc.). We are talking here about the so-called immediate detection of crime.

According to Collom [

9] (p. 146), a wide range of complementary currencies emerged in developed and developing countries in the 1990s in response to social, economic and environmental needs, in the form of skills exchange, modern barter trade, Zielony versions of reward systems and banknotes and coins. Fare and Ahmed take a different classification and describe so-called “northern” systems, which concern strata that can be diverse (e.g., the official use of two complementary currencies in Switzerland), and “southern” systems, which are generally formed during economic crises and are characteristic of socially impoverished strata [

5] (pp. 848–849) (in the opinion of the authors, from the point of view of the motives for which complementary currency systems were created, the classification of Fare and Ahmed is debatable. The motives for creating modern systems of complementary currencies can be described as hybrid, as they combine motives characteristic for both “northern” and “southern” systems. An example confirming this statement can be the Swiss complementary currency WIR, which due to the area in which it functions, fits into the assumptions of the “northern systems”, while due to the circumstances of its creation (i.e., as a direct response to the effects of the Great Depression of the 1930s), it fulfills the assumption of a currency typical of the “southern systems”).

The creation of the peer-reviewed International Journal of Community Currency Research in 1998 [

10] (pp. 53–68), the formation of IRTA on 31 August 1979 (The International Reciprocal Trade Association)—an association of more than 100 administrators of local currency systems cf. [

11], increased interest in economic processes by ecological circles, representatives of alternative economics, experimental economics, local development economics, the concept of sustainable development and the cooperative economy were also important for the popularization of the topic of local currencies. Complementary currencies are the subject of interest and scientific research of various disciplines and sciences: economics and finance, sociological sciences, anthropology, geography, and to a lesser extent, political science, law, psychology and development sciences [

12] (p. 346).

Complementary currencies in Poland have a history of over 100 years. Examples were complementary currencies issued primarily after the outbreak of the First World War, as well as after the crisis of 1929. Since February 2015, Poland has had only one complementary currency system (i.e., one complementary currency). It is Zielony—Polska Waluta Lokalna (Eng. Zielony—Polish Local Currency, hereafter referred to as: “Zielony” or “complementary currency “Zielony” or “currency Zielony”; monetary unit abbreviation: PLZ).

The main objective of the paper is to present the impact of lockdown and administrative restrictions in the COVID-19 pandemic on the functioning and circulation of complementary currency Zielony in entities that have joined the system of complementary currency Zielony in Poland. The main research problem of the article is formulated in the form of the question: “What is the impact of the lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic on the use of the complementary currency Zielony in commercial transactions by entities belonging to the system of this currency in Poland?”

The realization of the aim and the solution of the main problem required using various research methods. Among others, the following have been used in the article: the method of critical analysis of literature, the historical method, the statistical method, the comparative method, the observational method, the technique of informal expert interview, as well as analysis and synthesis, deduction and induction and abstraction.

The paper is a case study and consists of two main parts: theoretical and empirical. In the first part, the authors describe, among other things, the history of complementary currencies worldwide and in Poland, including the precursors of the analyzed instruments (tools), instruments and exchange systems recognized as examples of complementary currencies and contemporary complementary currencies worldwide. In this part of the article, the authors also review the literature and selected research positions concerning the complementary currencies in the world and characterize the complementary currency Zielony in Poland. In the second part of the article, the characterization of the research process is included, and along with the definition of the main goal and specific objectives of the research, the results of the research are included, and the conclusions from the analysis and realized research are presented. The article ends with a summary and bibliography.

The subject of the complementary currency Zielony in Poland, taken up by the authors, results, among others, from the scientific interests of the authors and the research topics realized by them, such as processes and phenomena occurring in the local economy and active participation in economic and social life in Poland, with particular emphasis on the Świętokrzyskie Province. The last of the indicated motives is particularly important in reference to the co-author of the article Dariusz Brzozowiec, who is the creator and leader of Zielony—Polish Local Currency, a publicist and a system analyst of local transaction systems.

This article is the first scientific article in the domestic and foreign scientific and popular literature in which the authors have determined the impact of the COVID-19 lockdown and pandemic on the circulation and functioning of the complementary currency Zielony in Poland in entities using the currency in realization of the payment function.

2. History of Local Currencies and Their Precursors

Blanc [

13] (pp. 2–3) states that in the history of complementary currencies, we can distinguish three historical periods indicating different circumstances of their emergence. The first period began at the end of the Middle Ages and was distinguished by the efforts of some kingdoms to unify their monetary systems and coins. This period was characterized by a great variety of money, including various forms of complementary currencies.

The second period, falling in the nineteenth century and the first quarter of the twentieth century, focused on the one money and the move toward an international monetary system, that is, a system built around contacts between national currencies and the creation of so-called issuing monopolies. The role of the complementary currency during this period was insignificant.

Interest in the subject of complementary currencies has been particularly evident in the world since 1916, during and after World War I, when countries plunged into destruction, poverty and unemployment were looking for concepts of reconstruction and development. An important role in the creation of complementary currencies in Europe during the period studied was played by German cities, which were able to use this mechanism to rebuild their local economies after the war. During the period studied, there were a lot of complementary currencies in Europe, the use of which made some countries, cities or regions rebuild very quickly from the post-war conflagration cf. [

13,

14] (pp. 103–116).

In the early 1930s, the interest in complementary currencies further revived and persisted in the context of severe budget constraints and rising unemployment caused by the Great Economic Crisis. This interest was not interrupted by the outbreak of World War II [

15] (pp. 47–61).

The third period, gaining in importance from the 1970s, is characterized by well-established and unified monetary systems of nation-states, but including competition of complementary currencies [

13] (pp. 2–3). In the history of the world economy, special attention to complementary currencies was paid in the second and third historical period highlighted above, i.e., in the periods of, among others, deep macroeconomic depression and the search for ways to revitalize it, change the rules of cooperation, etc. These factors have activated and further accentuated the important role of these so-called local experiments (opponents of this formulation claim that complementary currencies or complementary currency systems are a form of replication of certain solutions and proven mechanisms that were present in different economies of the world at different times (even nearly a century ago) in other markets. However, the effectiveness of complementary currencies depends on the administrators and users, as well as various economic factors, although in the literature, one can find examples of complementary currencies that have failed). During the period under study, complementary currencies served, among other things, to consolidate the structure of local business (American and Japanese examples), to build and develop communities, to create so-called local economies and to assist the unemployed to participate in the productive activities of the twentieth century [

16] (p. 12), [

17] (pp. 319–329), [

18]. The monetary experiments mentioned above were conducted by, among others:

As the first one, Robert Owen (1771–1859) founded the Labour Exchange in England in 1832 to fight against monetary and financial exclusion and to promote egalitarian values by basing the exchange on a standard of time value and so-called “fair labor exchange” in which craftsmen traded their products and services;

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809–1865), who in 1849 in France proposed a project based on free credit managed by a so-called “people’s bank” with bills of exchange to replace the official currency [

19] (pp. 239), [

5] (pp. 848–849);

Silvio Gesell (1862–1930), who postulated the functioning of non-interest bearing (or even with so-called “negative interest”) and non-convertible social money, so-called “free money”, under the control of users. He developed the theory of complementary currencies discussed by economists including John Maynard Keynes and Irving Fisher. Debates on Gesell’s ideas took place in the context of the economic turmoil in Europe from the beginning of World War I to the mid-1920s and in the context of the crisis of the 1930s marked by a process of deflation. Although Gesell’s proposals for complementary currencies did not apply to the local economy, no less the experiments that were initiated on the basis of his ideas always had a local character [

13] (pp. 11–13). Additionally, relevant to Gesell’s experiments is the concept of demurrage and negative interest (already known from the recommendations of the bishops of Weimar, who between 1130 and 1430 introduced one-sided minted money, so-called Bracteates, as a means of payment (so-called Weimar bishops brakteats; Ger. Brakteaten der Weimarer Bischöfe) [

20,

21].

With regard to the aforementioned Gesellian experiments, significant for the history of complementary currencies were the currencies based on a system of stamped banknotes in the city of Wörgl in Austria in the 1930s intended to stimulate the economy by creating a negative incentive against the hoarding of banknotes [

22] (p. 6) and which contributed to the so-called “economic miracle “in the city of Wörgl” and the Swiss cooperative WIR founded in 1934 in Zurich, promoting the doctrine of “interest-free money”, which initiated the WIR Frank (code: CHW, number: 948; since December 2004) and WIR Euro (code: CHE, number: 947) listed as official currencies in Switzerland cf. [

23], functioning today as local barter currencies. Other examples of complementary currencies used alongside state currencies were money notes and Notgelds and Rentenmarks in Germany running alongside the German mark, which could not be used and transferred outside Germany, as well as the so-called regiogeld, i.e., several regional money initiatives in Germany coinciding with place-names [

24,

25] (pp. 179–181), [

26] (pp. 157–177).

The important role of the development of complementary currencies in the world has also been played by:

Scrip that emerged in the first half of the twentieth century in the United States, allowing exchange for goods or services sold by the issuer [

27] (pp. 437–447), [

10] (p. 55) and the local voucher system in France in the 1950s;

Local exchange and trading systems, e.g., LETS (Local Exchange Trading System) designed by Michael Linton in 1983 in the Comox Valley of Vancouver Island, Canada, to help the local economy, which began to decline as a result of, among other things, massive unemployment resulting from the closure of local industry [

28] (pp. 114–132), [

5] (pp. 848–849) with other local variants including the LECOP (Letra de Cancelación de Obligaciones Provinciales; English. Letter of Cancellation of Provincial Obligations) and the crédito of the global network of multilateral barter clubs Red Global de Clubes de Trueque Multirecíproco RGT in Argentina, SEL in France (Système d’Échange Local), Zielony Dollar Exchange in Australia and New Zealand cf. [

29], Tauschring exchange circles, Tauschkreis in Germany, the CES (Community Exchange System) in Africa [

7] (pp. 10–11) or Sardex in Sardinia cf. [

30] (pp. 1–21) (the latter of the indicated systems is of significant importance in the European mutual credit market. It was established in 2009 and has about 3200 member firms in Sardinia and the same number in various Italian provinces. In 2018, the volume of transactions in the complementary currency Sardex in Sardinia amounted to 43 million euros cf. [

30] (pp. 1–21));

The Japanese Eco-Money Network, which is Japan’s complementary monetary system, incorporating the concept of a regional currency called “eco-money”, established in 1998 and operating at regional and local levels and providing incentives for new forms of production, distribution and consumption, some of which are based on social and environmental values. The Eco-Money network was established to support different regions of Japan in introducing new currencies, all of which are considered experimental economics tools and aim to enhance community integrity, support the creation of a sustainable economic environment and maintain a sustainable natural environment [

22] (p. 10);

Time-based currencies, time banks and hour systems (e.g., Hours System in Ithaca, northern New York), which are forms of currency where the unit of currency is a unit of time. It is a tool for small communities where people help each other. Its purpose is to boost the local economy by keeping money circulating locally. This system ensures that bottlenecks do not slow down trade and users do not experience difficulties in spending local currencies that are part of the Hours System [

19] (p. 234), [

31] (pp. 4–10), cf. [

32] (pp. 1–17).

In other parts of the world, when state money was scarce, various private institutions issued their own money. Complementary currencies in Poland included private payment vouchers of the Hrubieszów Agricultural Society from the nineteenth century, porcelain and stoneware money (coins) issued in the 1920s by mines, bakers, municipalities, as well as cities (e.g., Tomaszów Mazowiecki, Zielona Góra, Głogów, Tarnowskie Góry, Zabrze, Kończyce), unions (e.g., Association for the Defense of Polish Industry in the 1930s) or banks (e.g., PeKaO commodity vouchers, called “Polish dollars”, issued in the 1960s and 1970s by Bank Polska Kasa Opieki SA) [

1] (pp. 889–899). In the period studied, complementary currencies functioned in Polish cities alongside the official currency—the state currency. These currencies did not have the features of state money and could not be used to pay taxes, but they could be used, for example, to buy basic products or to pay for services.

Today, in several countries around the world, complementary currencies are recognized as fully fledged and valid means of payment. The best-known examples of complementary currencies, functioning alongside national currencies (apart from the aforementioned WIR Frank and WIR Euro in Switzerland), are:

Mvdol in Bolivia (code: BOV, number: 984), used in parallel with Boliviano, the monetary unit of Bolivia (code: BOB, number: 068);

Chilean Unidad de Fomentos (code: CLF, number: 990) and Yuan Renminbi (code: CNY, number: 156) in Chile, used in parallel with the Chilean Peso (code: CLP, number: 152);

Cuban Convertible Peso (code: CUC, number: 931), used in parallel with the Cuban Peso (code: CUP, number: 192);

Rand in Lesotho (code: ZAR, number: 710), used in parallel with Loti (code: LSL, number: 426);

Mexican Unidad de Inversion in Mexico (UDI) (code: MXV, number: 979), used in parallel with the Mexican Peso (code: MXN, number: 484);

The Namibian Rand (code: ZAR, number: 710), used in parallel with the Namibian Dollar (code: NAD, number: 516);

Currency of Uruguay in indexed units (URUIURUI) (code: UYI, number: 940), used in parallel with the Uruguayan Peso (code: UYU, number: 858) [

23].

To sum up, experiments with complementary currencies in the world in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries took place mainly during crises and economic fluctuations, when the analyzed compensation tools realized mainly a protective function. Their issuance was mainly carried out by public authorities, civic association, companies as well as banks, and the need for them was mainly due to macroeconomic factors, rather than social or protectionist factors, as it is the case today [

13] (pp. 13–14).

3. Literature Review

In the literature, it is difficult to see a clear scientific discussion of the benefits and positive effects generated by the functioning of a complementary currency. Moreover, analyses and results concerning the functioning of complementary currencies in the world are referred to analyses and results that are derived from measurements and calculations that are applied to the economy as a whole and for this reason (i.e., measurement error), do not show the real benefits (restrictions, threats?) of the functioning of a complementary currency in the local economy and to the entities operating in it. The following literature review and scholarly discussion address some of the main aspects that complementary currencies are associated with.

The first presents the impact of complementary currencies on a country’s economic development. From the point of view of macroeconomics, the optimal level of economic sustainability would be achieved by such an economy in which goods consumed in a region were produced in the same region using local resources and local labor. Such a relationship Schumacher called the so-called “economy of sustainability” [

33]. The rhetoric that complementary currencies are conducive to promoting sustainable development, improving economic conditions, strengthening the economic position of the region and the position of citizens in meeting basic and supernumerary needs, supporting the exit from economic marginalization, and having a significant impact on monetary policy, the economy and the growth of local wealth has been presented by, among others, Williams [

34] (pp. 1–11), Seyfang [

35] (p. 60), Graugaard [

36] (pp. 243–260) and Seyfang and Longhurst [

37].

The results of research emphasizing the importance of complementary currencies in creating conditions for regional economic development and their significant role in fostering economic governance are contradicted by the results of research conducted, inter alia, by Collom [

38] (pp. 1565–1587), in light of which complementary currencies (on the example of the United States) do not contribute to the promotion of local economic development in periods of economic and financial stability. Solomon [

18] and Schroeder and Miyazaki and Fare also talked about their low contribution to large-scale economic development, barriers and difficulties arising from their use [

39] (pp. 31–41).

The results of research on the Swiss WIR presented by Stodder are also relevant to the above discussion [

40] (pp. 79–95). According to them, the described Swiss local currency has a countercyclical effect. WIR money does not “replenish” the supply of Swiss francs but descends them, and the effect of increased WIR turnover on prices is not inflationary but rather anti-deflationary. The findings on the countercyclicality of WIR also support the considerations of Lietaer, Ulanowicz, Goerner and McLaren [

41] (pp. 89–108) and Stodder and Lietaer [

42] (pp. 570–605), according to which unregistered firms provide products as well as credit to smaller registered firms. The velocities of registered firms and the balances of unregistered firms play a leading countercyclical role. Complementary currencies facilitate transactions that would not otherwise occur, connecting otherwise untapped resources to unmet needs and encouraging diversity and interconnectedness that would not otherwise exist.

The second scholarly discourse on the economic benefits of complementary currencies indicates that they foster trust, cooperation and reciprocity [

12]. Nowadays, they are mainly part of the so-called community currency systems. In light of the findings of Jacob, Brinkerhofaf, Jovic and Wheatley [

43] (pp. 42–56), they function primarily as a form of social and cultural capital and contribute little to increasing access to goods and services (in the United States). They are similarly defined by Blanc and Fare [

2] (pp. 298–299) following Allen [

44] in considering complementary currencies as tools to promote social rather than economic values and Mauldin [

45] (p. 464), who by local currency understands specialized instruments to promote community goals of cultural, social, economic, human and infrastructure capital. The researcher also recognizes it as part of a relocation movement that aspires to “increase local exchange activity and foster all the positive cultural and social outcomes of greater local employment, mutual self-help and cooperation” and that reflects the unique characteristics of a community by, among other things, supporting and promoting local goods or services [

45] (p. 464). The aspect of relationship building, social support and personal comfort was also pointed out by, among others, Richey [

46] (pp. 69–88), Letcher and Perlow [

47] (pp. S292–S299), Graugaard [

36] (pp. 243–260) and Siqueira, Honig, Mariano and Moraes [

48] (pp. 711–726).

Blanc and Fare [

2] (pp. 300–304) state that complementary currencies contribute to the creation of rules, standards and values that allow the establishment of relationships within a community and are considered a symbol of belonging to the community. They are also identified with a mechanism of social mediation that in itself generates closeness, trust and cooperation and promotes a sense of community. According to Rauschmayer, Polzin, Mock and Omann [

12], complementary currencies (referred to by the authors as community currencies), and especially the process of creating them, are an example of contemporary small collective initiatives and an explicit act of community participation. They are based on the solidarity and cooperation of individuals who voluntarily commit to a program for bringing about change in the local community. According to the authors, these are currency systems in use around the world that are complementary to national currencies, but at a local level, responding to the opacity of the standard financial system. Complementary currencies also aim to create or strengthen an economy rooted locally, giving value to objects, skills and competencies that allow for the creation of social ties in the neighborhood and incorporate elements of collective action, i.e., the involvement of people and cooperative and voluntary action for the interest of the local community. According to the authors, complementary currencies can be seen as an effort to combine market activities, public debates and community participation in a hybrid form. Users of complementary currencies engage in market activities when they purchase goods and services through the complementary currency. At the same time, they can provide a forum for discussing alternatives to capitalist markets, and participation can be a form of political engagement cf. [

12,

49].

Another group of social scientists cf. [

50,

51] has analyzed the ethical and political motives behind the creation and functioning of complementary currencies, considering them as so-called “forms of modern monetary competition” and tools contributing to the creation of so-called economic democracy. Trust also plays an important role in building a system of complementary currencies, which is certainly difficult to build and requires an extensive network of users who approve participation in the system [

2] (pp. 299–300).

The theories presented in this part of the study refer primarily to the functioning of the complementary currency in economies as a whole, and to a lesser extent, refer to the results obtained by local economies or their entities. They also do not deal with the role of complementary currencies in periods of economic and financial crises, as well as those that do not have an economic background, but affect the functioning of an economy, and especially the entities operating in it. Zielony—Polish Local Currency, described later in this paper, only fulfills the assumptions formulated by economic thinkers studying complementary currencies around the world.

4. Characteristics of the Zielony—Polish Local Currency

Zielony—Polish Local Currency is the only complementary currency operating in Poland. It was created in February 2015 in Starachowice (Świętokrzyskie Province; Poland) by Dariusz Brzozowiec, project leader, co-author of this article, as well as a publicist and a system analyst of local transaction systems, the participant and speaker in many conferences devoted to the topic of alternative currency systems in Poland and worldwide. The project preceding the complementary currency Zielony in Poland was the complementary currency Dobry, created in February 2014 also by Dariusz Brzozowiec, for which activity was suspended in September 2014. Until the creation of the Zielony, another complementary currency, Piast (PLP), was also registered in Poland in 2014, the activity of which was suspended by its creators in 2015. A characteristic feature of all the aforementioned complementary currencies in Poland is that they were created in the same region (i.e., Świętokrzyskie Province), among other things, as a response to the region’s economic problems related, among others, to unemployment.

The model of complementary currency Zielony in Poland adheres to the patterns and models tested in Switzerland and Belgium (on the principle of so-called financial democracy), in particular Sardex, Res-Euro in Belgium and WIR Franc, which is the second transaction currency in Switzerland.

The complementary currency Zielony supports transactions carried out by various business entities and individual customers across the country. In 2021, more than 500 companies and 3000 individuals were operating in the system of complementary currency Zielony [

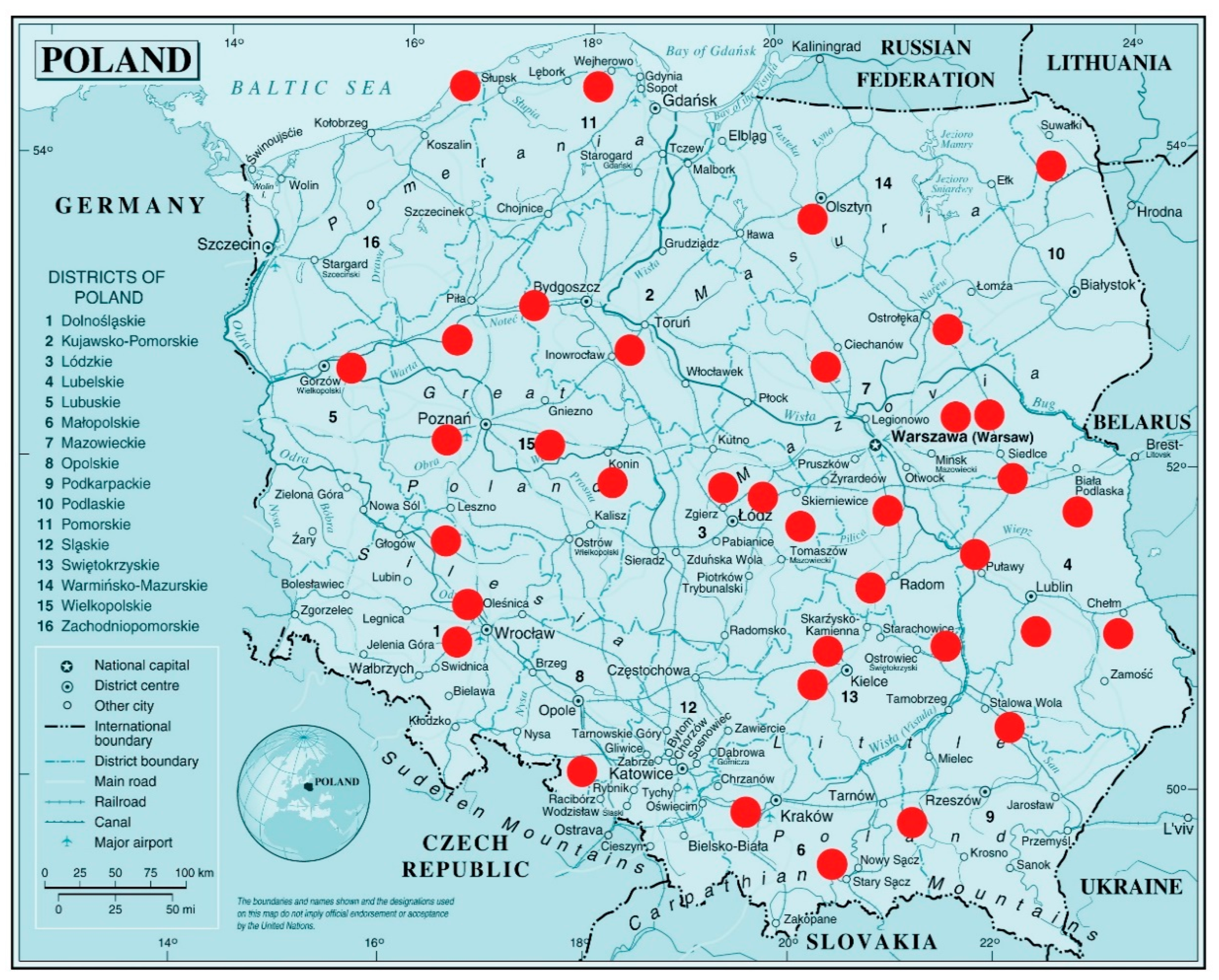

52]. The approximate distribution of entities that joined the Zielony complementary currency system in Poland between 2015 and 2021 is presented in

Figure 1.

The complementary currency system Zielony is a compensation exchange system (so-called clearing house) and offers a cooperation program for Polish companies and individual customers, allowing them to cooperate using the complementary currency through greater willingness to cooperate, simpler sales and interest-free financing. Entities joining the project gain, among other things, a contact to all other participants of Zielony through a common transaction system, local events and a cooperative attitude.

The Zielony currency system functions in two layouts—variants:

On the business-to-business (B2B) level, following the Swiss model, in the environment of small and medium-sized enterprises (the Polish complementary currency project is promoted by the Association of Entrepreneurs and Employers in Poland), initiated in February 2015, which use Zielony to sell services and products. This arrangement allows companies as part of their marketing activities to be introduced to each other and establish new business contacts, acquire new business and private customers, integrate the small and medium business community, receive quick access to new contractors and offer so-called “spare capacity”. In the European system of complementary currencies, it is characteristic that it does not take into account corporate organizations and large players with an international scope because the introduction of a large player does not leave room for local players;

At the business-to-consumer (B2C) level, where there are companies in the retail business sector (e.g., food retailing) that offer bonuses (rewards) for products or services purchased by the consumer in the form of Zielony as part of a loyalty system (so-called multi-loyalty project). As part of this system, the consumer uses Zielony application within which he or she can transact in Zielony at businesses that are part of the system.

The revenue model of Zielony is similar to the models of the aforementioned currency systems and includes commission fees (from 0.0% to 3.9%) on completed transactions charged only on the value of Zielony in transactions, not on Polish zloty, and an annual fee (890 PLN net or 1245 PLN net or 3045 PLN net varying depending on the package chosen by the entity joining the system). In creating the Zielony currency project, the creators did not use venture capital or public funds, and the venture itself has been profitable since 2016.

Entities starting cooperation in the Zielony currency system receive a debt in the amount of 1000–8000 Zielony (the debt of the Zielony currency is interest-free). Entities joining the system of the complementary currency Zielony in Poland are offered by the currency’s creators a choice of three start-up packages: Mini Package (890 PLN net/year), Standard Package (1245 PLN net/year) and Premium Package (3045 PLN net/year). The list of services and benefits available in each package is presented in

Table 1.

Zielony is a money substitute and acts as a means of payment in specialized communities where payments are made. It is a contractual means of payment, operating in accordance with commercial law and banking regulation and a full-fledged example of how trade can be conducted using a contractual unit of account. It is also a multilateral credit system and a contractual form of payment used among companies and individuals who use it alongside domestic money for transactions in the domestic market [

54] (pp. 1–4). It is also a second complementary tool for building the local community. From the perspective of Polish law, the Zielony back is a clearing currency, a tool of the compensation trade system (i.e., a form of compensation trade) combined with a loyalty program, and does not exist as a physical unit of payment. Within the scope of accounting and tax policy, it is an accounting record of the Polish zloty regulated by the Polish tax law and has obtained individual tax interpretation. Issuance of complementary money Zielony is based on the principle of the Mutual Credit System (MCS) (The Mutual Credit System (MCS) is a standard creating local currency and barter-settlement transaction systems. It is based on opening settlement accounts for participants (companies and individuals), where the administrator allows debiting under certain account conditions. For security reasons, the system limits the capacity of settlement accounts so as to avoid excessive accumulation of settlement units on account of a single user. The possibility of combined transactions is also allowed, where payments are made only in a certain part with billing units and the rest in the traditional way [

52]), which means that the issuer of complementary money can be each of the business users (entrepreneurs), while the administrator serves only as a guarantor that the established model of money will be observed. The complementary currency system Zielony in the MCS standard does not have an issuing institution. Each participant, according to the rules set by the administrator, leading to a negative balance, makes an issue. The issue, or debts, should be properly secured depending on the amount of the debt. Here, the phenomenon of dispersed emission appears, which is carried out by the participants of the system [

52].

There is a debt and credit account in the system. An account overdraft occurs when the participant has made a purchase but has not made a sale yet. The credit on the account informs that the participant has already made a sale. The sum of the debt (with a negative balance) and the sum of the credit (with a positive balance) is always zero. The policy of granting the ability to debt a participant’s account is at the discretion of the administrator and a deliberately created control body composed of system participants. For this purpose, the users of the system form a separate cooperative entity that takes a minimum of 6% ownership of the administrator. The cooperative establishes a board of directors whose administrator allows for ongoing oversight of user accounts. The debt policy (Credit Matrix) is established jointly by a and the cooperative board. The account records reflect all transactions made with the complementary currency and are kept by the administrator for 6 years in an electronic form. Once a year, the administrator shall make a paper copy certified by responsible people of all balances of all accounts in the system. The paper copy is filed in the archives of the administrator and the board [

52].

Debts in the system of complementary currencies are treated in the light of economic law on the principle of monetary liability. It is the administrator’s duty to assert claims on this account, and if they arise, they take place before competent authorities (commercial courts) [

54] (pp. 1–4). Zielony is not convertible into other currencies (including the state currency), and it cannot be freely transferred outside the region where it operates. It is contractual, non-interest-bearing (does not cause debt or inflation), non-convertible, cheap to use, focused on local business and local communities and gives a competitive advantage in the industry and geographic area where the currency operates (i.e., Świętokrzyskie, Małopolskie, Mazowieckie provinces). For the local community, it can be a transactional medium that offsets the problems connected with money shortage and prevents the effects of capital flowing out of the country. It is not a speculative currency, which means that there is no possibility to invest it on the stock exchange, but it is considered a transaction tool in the real economy.

Zielony is considered only as a transactional medium that does not have the properties of hoarding and speculation (i.e., it is not possible to sell or buy Zielony, although it can be earned or received as a gift), and it is also excluded from global reach in favor of serving the local economy. One of the conditions for its effectiveness is the speed of circulation (circulation). It can support the satisfaction of needs at a rapid pace. The described complementary currency makes the interest in local production and distribution increase and allows the so-called local employment and local construction of economic ventures, including the construction of economic cycles and circulations that give work and build local wealth.

5. Methodology

The adopted purpose of the study is completed by the analysis of a case study of the only complementary currency in Poland—Zielony. The objective of the study was to analyze the impact of lockdown and administrative restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic on the functioning of the complementary currency Zielony in Poland in service, trade and manufacturing entities that have joined the complementary currency system between 2015 and 2021. The specific objectives set in the research process were:

Determining the number of transactions expressed in Zielony and the volume of turnover in Zielony in the period before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in entities that have joined the analyzed complementary currency system;

Indicating the relationship between the type of economic activity (i.e., service, commercial, manufacturing) of the entity that has joined the system under analysis and the operation of the system and the circulation of the complementary currency Zielony during COVID-19;

Showing the interdependence between the value of transactions carried out using Zielony by entities operating in the complementary currency system and the value of transactions carried out in the national currency PLN by all entities in the Świętokrzyskie Province and in Poland during the lockdown and the COVID-19 (the lockdown in Poland occurred from 14 March 2020 to 18 May 2020 and from 24 October 2020 to June 2021. The total lockdown affected service entities, including restaurants, hotels, fitness entities, etc.).

The thesis adopted in the study is as follows: “The complementary currency Zielony in Poland is not a tool that would support the functioning of entities (among others in the local economy) during a crisis of a non-financial nature (i.e., such as the COVID-19 pandemic), on which lockdown and other restrictions have been imposed, the consequence of which is, among others, the weakening of economic activity in various sectors of the local economy, in particular with regard to entities of a service nature.” In the case of the complementary currency Zielony in Poland, these entities account for about 80% of the system.

The main research problem was formulated in the form of the following question: “What is the impact of the lockdown and other restrictions imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic on the circulation of Zielony in the local economy and the ability to use this currency in commercial transactions by entities belonging to the system?”

The main research methods used in this part of the study were: the statistical method, comparative method, observational method, analysis and synthesis and abstraction and information retrieval method with the technique of a free direct expert interview conducted with the founder and the leader of the complementary currency Zielony, Dariusz Brzozowiec.

In the implementation of the study, among others, two main data were used: monthly number of B2B and B2C transactions conducted in Zielony in Poland from March 2015 to June 2021 and monthly turnover value in Zielony in the B2B and B2C sectors in Poland between March 2015 and June 2021 (in PLZ).

From the point of view of research organisation, it should be mentioned that these are the only figures that the system administrator can generate from the transaction software of the complementary currency Zielony. They come from internal statistics of the system of the analysed complementary currency and are not published in any statistical sources in Poland or abroad (e.g., Central Statistical Office in Poland, regional branches of Central Statistical Office, private research institutions and agencies, etc.). They are authorized. Their authenticity and conformity with facts has been confirmed by the leader and administrator of the system and co-author of the article, Dariusz Brzozowiec

Other data taken from the Zielony complementary currency system and used in the conducted analysis are: number of transactions and value of turnover in Zielony in Poland between January 2019 and June 2021 for a sample restaurant X services company in Poland and monthly turnover values of a selected deli-type store Y in Poland between January 2019 and June 2021 (in PLN and PLZ). The statistics on the turnover volume and number of transactions carried out by the two selected business entities: restaurant X (classified in the complementary currency system as a service entity) and deli-type store Y (classified in the complementary currency system as a commercial entity), are illustrative and show the trend that occurs in a given industry during the lockdown period of the COVID-19 pandemic. The lack of reference to the statistics of the larger number of service and trading entities that joined the Zielony complementary currency system is due to, among other things, the inability to obtain the aforementioned data from individual entities (for various external reasons) and the inability to filter in the system individual entities for the implementation of the survey. However, these limitations do not affect the capture of the economic situation of the indicated entities during the lockdown period.

The research section also includes statistics on, among other things, the value of turnover in the Świętokrzyskie region and in the Polish economy during the COVID-19 period, the revenue earned by food houses in Poland in 2020–2021 and by grocery stores in Poland not subject to lockdown and other restrictions.

6. Results and Discussion

According to the presented literature review, complementary currencies have different impacts on the functioning of the local economy. Economic practice and the presented data indicate that complementary currencies contribute to the building of local capital, foster the creation of conditions for sustainable development, as well as serve as a tool to support the activities of entities of the local economy that operate in it. Although this significant role of complementary currencies in the development of local entrepreneurship and micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises is not confirmed by aggregated values of economic performance indicators, the influence of complementary currencies on the functioning of the local economy is expressed, among others, by an increase in the number of users joining the complementary currency system within 1 year, an increase in the number of completed transactions and an increase in the value of turnover from the sale of goods and services expressed in the aforementioned currency within a certain period of time. These relationships are visible in the case of the complementary currency Zielony, which has been the only currency operating in Poland since 2015.

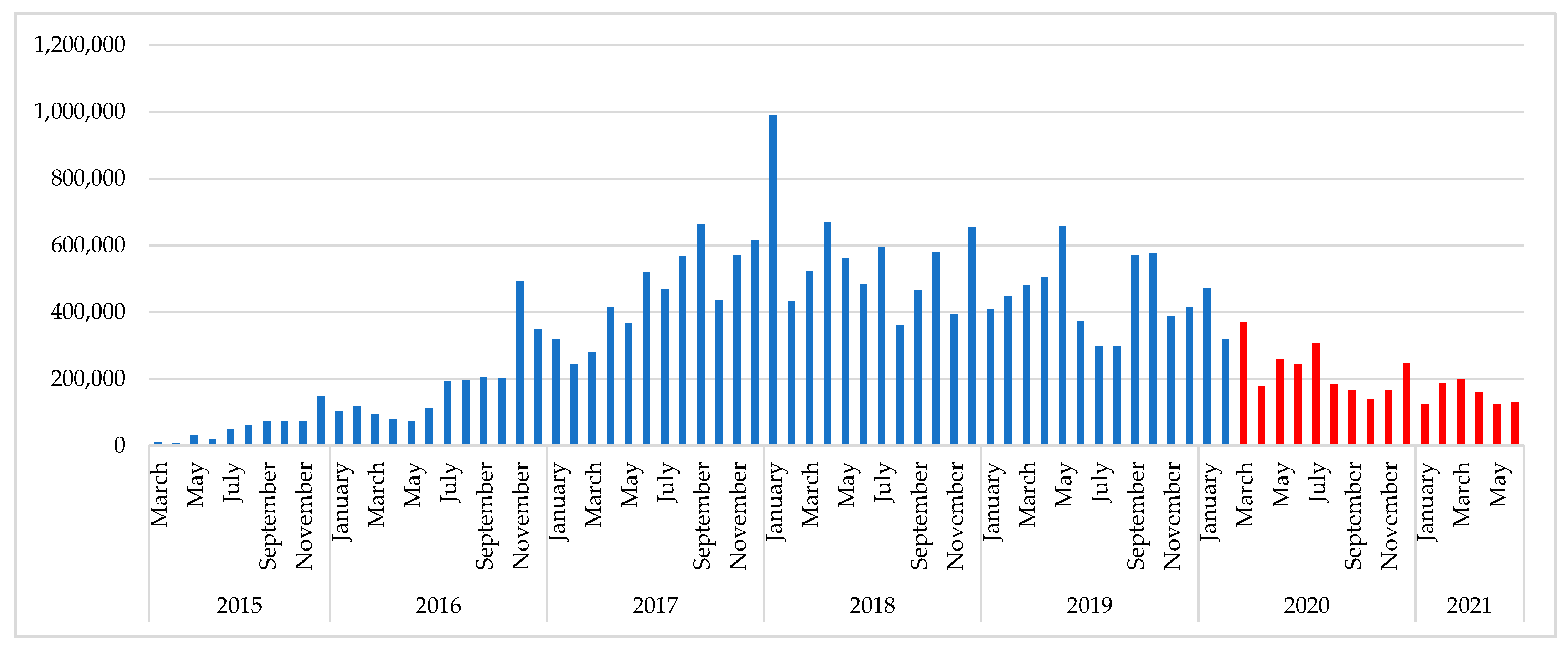

The analysis of the figures shows that statistics on the number of transactions carried out in Zielony and the value of trading in Zielony during the period from March 2015 to March 2020 (cf.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3) (and from January 2017 to March 2020; cf.

Table 2), i.e., in the period before the COVID-19 pandemic, increased steadily [

1] (pp. 893–895). The number of entities joining the system of the complementary currency in Poland was also increasing, both those that carried out transactions on a B2B as well as B2C level. A distinctive feature for this period was also the fact that the complementary currency Zielony expanded its geographical range and diversified its share in other regions of Poland than the province of Świętokrzyskie, where it was initiated. The largest share in the implementation of transactions using the complementary currency Zielony in the period under review was recorded by service providers (as noted earlier in this article, representing about 80% of the entities that have joined the Zielony complementary currency system). The increase in individual parameters in 2015–2020 in relation to Zielony currency resulted from its circulation in the economy, the possibility of using it by commercial entities and individuals in transactions, as well as supplementing by it the deficit of money commonly prevailing in the local market. The complementary currency Zielony in the local economy before the disclosure of the COVID-19 pandemic was a tool contributing to the support of activity of micro-, small- and medium-sized entities.

Since 14 March 2020, i.e., the introduction of the first lockdown in Poland due to the declaration of an epidemic emergency due to SARS-CoV-2 infections, statistics on the aggregated number of transactions conducted in Zielony (

Figure 2) and the aggregated value of trading in Zielony (

Figure 3) obtained by entities that have joined Zielony have declined. The first lockdown included, among other things:

Stores (whose main activity consists of trading in textiles, clothing products, footwear and leather products, furniture and lighting equipment, radio and television equipment or household appliances, stationery and book products);

Event and exhibition sector;

Restaurants and other permanent food houses (i.e., cafeterias, fast food restaurants, dairy bars, ice cream parlors or pizzerias);

Entertainment and recreational activities, in particular involving the operation of meeting places, clubs, including dance clubs and nightclubs, and swimming pools, gyms or fitness clubs;

Tourist accommodations and places of short-term accommodation, i.e., colony centers and other holiday accommodations (holiday centers, training and recreation centers), guest accommodation, cottages or huts (without staff), rural farms (agrotourism) and youth and mountain shelters.

The last three groups of entities listed above are the main participants and beneficiaries of the Zielony complementary currency system in Poland in the service sector.

All entities providing the aforementioned services in the Świętokrzyskie voivodship recorded a decrease in the value of turnover in the first lockdown (from 14 March 2020 to 18 May 2020) and the second lockdown (from 23 October 2020 to 15 May 2021). The downward trend is particularly noted by service companies, which had to contend with lockdown and legal constraints during the pandemic period. This finding coincides with the results presented in the Socio-Economic Situation Communication in March 2021 [

55] (pp. 17–19), according to which the businesses most frequently signaling changes related to the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown were firms engaged in activities related to culture, entertainment and recreation (5.9%) and accommodation and catering (5.6%). As the reason for changes in their business activity during COVID-19 and the lockdown, they gave a change in the number of orders.

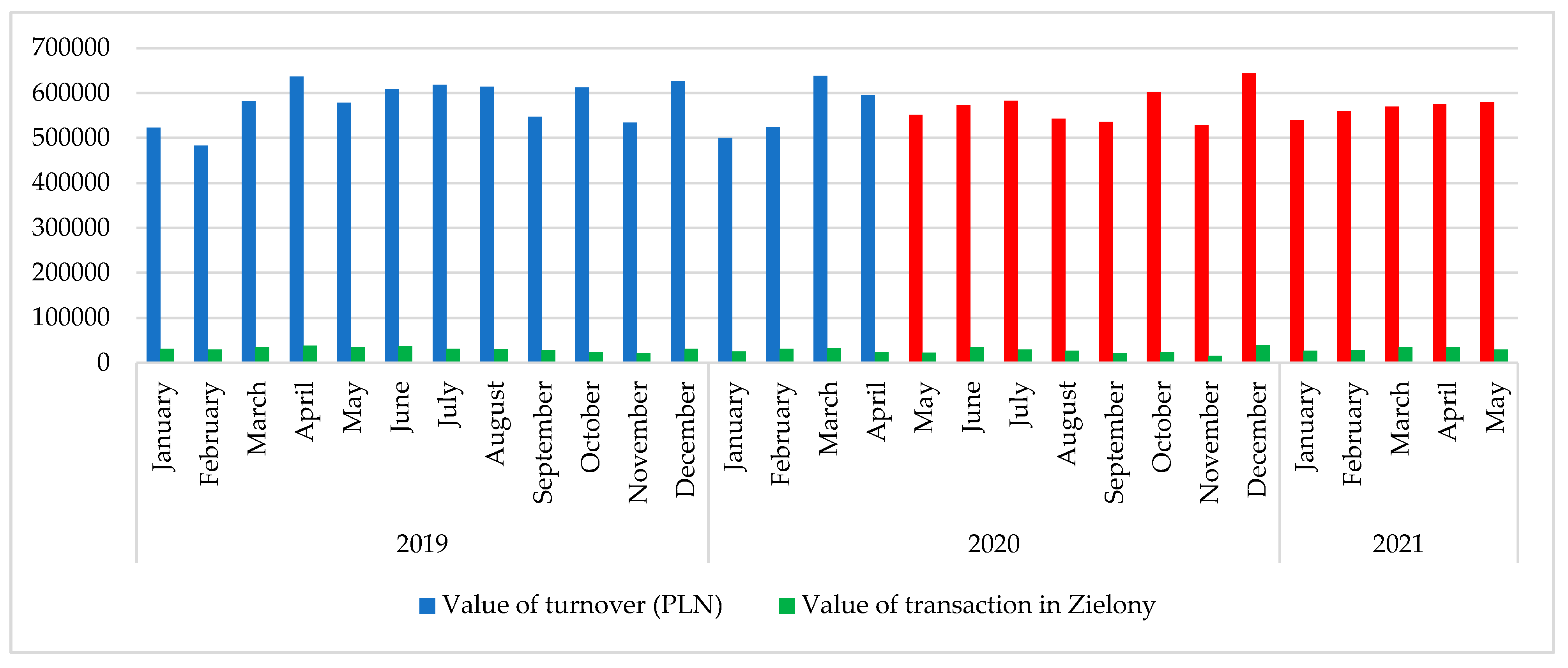

The data in

Figure 3 confirms the decline in turnover values of entities participating in the Zielony complementary currency system during the COVID-19 pandemic period, especially in the lockdown period. A similar relationship was shown by the turnover values of entities operating in the Świętokrzyskie Province and in Poland during COVID-19. For example, in March 2021 in the Świętokrzyskie Province, a decrease in this area was indicated by 0.8% of entities (compared to 0.7% in February 2021), and in the country, 0.6% (compared to 0.7%). The section with the largest share of the decline in orders in the studied province was the activities related to culture, entertainment and recreation, while in Poland, accommodation and catering [

55] (p. 18). For comparison, in April 2021 in Świętokrzyskie Province, the businesses most likely to signal changes related to the COVID-19 pandemic were accommodation and catering (5.3%), i.e., companies that were subject to total lockdown. A similar relationship was also seen nationwide (5.1%) [

57] (p. 19).

In June 2021, the change in the number of orders was most often indicated as the reason for changes in business activity related to COVID-19. In the studied period, a decrease in this area was indicated by 0.1% of entities in Świętokrzyskie Province (compared to 0.3% in May 2021), and 0.3% nationally (compared to 0.5%), while an increase was indicated by 0.1% (compared to 0.4%), and 0.5% nationwide (compared to 0.6%). The section with the largest share of the decrease in orders in the Świętokrzyskie Province was manufacturing (in the country—other service activities). As for the growth, the highest share was characterized by administration and support activities, and nationwide, accommodation and catering [

58] (p. 18).

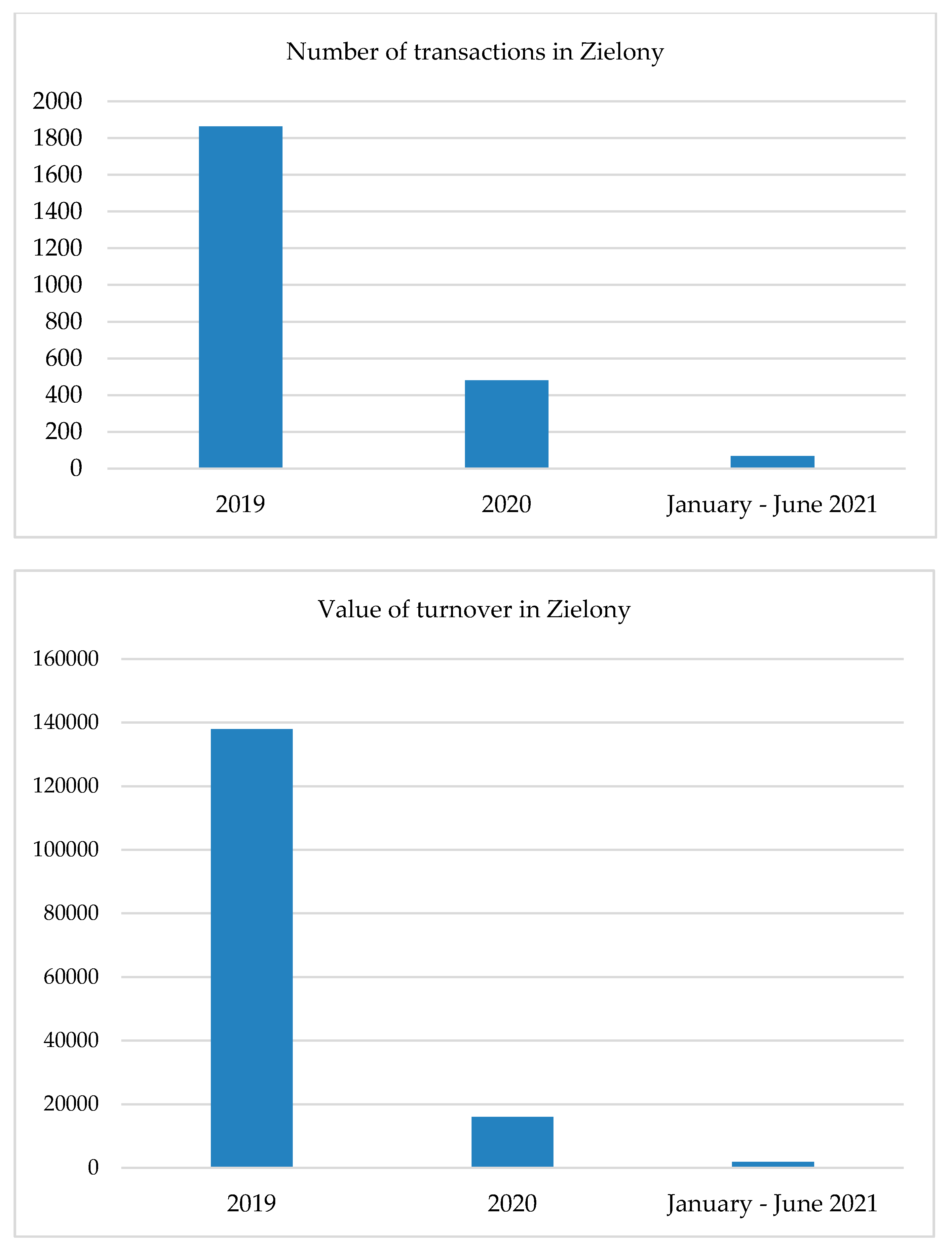

As mentioned earlier, the structure of the Zielony’s complementary currency system is made up of 80% service entities, 10% trade and 10% manufacturing. Lockdown and restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic negatively affect service providers (which within the structure of the system include, for example, hairdressing salons, beauty salons, fitness and health and beauty salons, but also hotels and restaurants), which is expressed, among other things, by a decrease in the number of transactions carried out in a given period and, with it, a decrease in the value of turnover expressed in Zielony. This relationship is shown by the example of a selected restaurant services company X, which in 2019 carried out 1864 transactions using the complementary currency Zielony; in 2020, the number of transactions in Zielony was almost four times lower and amounted to 480 transactions, while in the first half of 2021, the number of transactions in Zielony was 68. Considering the value of turnover for the studied entity, in 2019 it was 138,000 Zielony; in 2020, the turnover was 16,000 Zielony, and from January 2021 to June 2021—1861 PLZ (

Figure 4) (assuming that the monthly revenue of the restaurant X in 2020 was about 60,000 PLN) [

59]. At this point, it should be stressed that in the periods not covered by the lockdown in Poland (i.e., from 18 May 2020 to 24 October 2020 and from 15 May 2021), the value of turnover of service providers covered by the lockdown, expressed in the complementary currency Zielony as well as in Polish zloty, did not reach the level of value before the first lockdown.

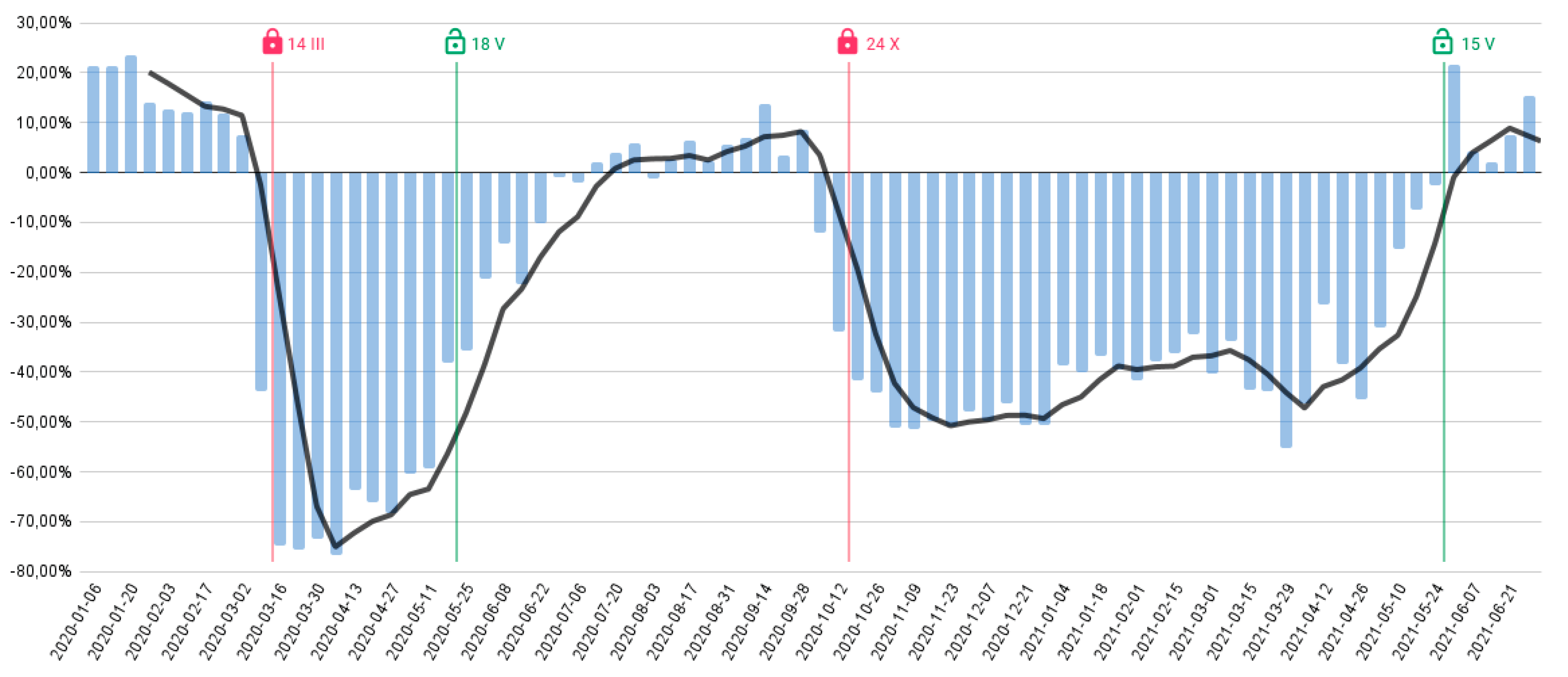

The above results regarding the significant decrease in number of transactions and value of turnover in Zielony in 2019–2020 for a sample restaurant company X in Poland confirm, among others, the results of the Deloitte report [

60] (pp. 1–16) and the results of the PosBistro 2021 study [

61] (pp. 1–62). In light of the Deloitte study, COVID-19 in particular threatens the stability of the largest number of firms in accommodation and catering. According to Deloitte’s data, the worst ratings for the business climate in accommodation and catering in Poland are related to the COVID-19 pandemic, and in particular to the restrictions imposed on the industry. The reduction of restrictions in the summer of 2020 has temporarily reduced the concerns of entrepreneurs who operate in this industry [

60] (pp. 5–6). A significant drop in revenues in the analyzed industry occurred on the day of the first lockdown announcement in Poland (i.e., 13 March 2020. From 14 March 2020 to 18 May 2020, i.e., the period of the first lockdown), revenues of this industry expressed in PLN were lower by 60–80% depending on the segment, and then they started to grow again after the restrictions were lifted in May 2020. The second lockdown in Poland, which lasted from 24 October 2020 to 15 May 2021, resulted in another decline in revenues in the analyzed industry by 50–55% [

61] (p. 4). The above dependencies are presented in

Figure 5.

Unlike the service entities, the number of transactions and the value of turnover obtained both in Zielony (as PLZ) and Polish zloty (as PLN) by trading and manufacturing entities belonging to the complementary currency system during the lockdown and COVID-19 periods are similar to the values obtained by these entities before the pandemic. This is due to the fact that the aforementioned entities that make up the structure of the Zielony complementary currency system during the period under study were not subject to lockdown restrictions and conducted trading and manufacturing activities without restrictions. This relationship is shown by the results of, among others, a deli-type store Y, shown in

Figure 6.

For entities in the food industry (as well as the dietary supplement industry) that make up the structure of Zielony, during the COVID-19 period, including lockdown, there was also an increase in the number of transactions and an increase in PLN and in Zielony sales turnover during the pandemic period in relation to the values that these entities were achieving before the first lockdown in March 2020. During the pandemic period, these entities increased transaction execution in Zielony due to, among other things, consumer purchasing decisions, including meeting transactional demand. During the lockdown period, consumers did not use the offer of service companies (as they had to suspend their activity during this period), and Zielony they had were used to meet their current consumption needs, mainly purchasing food from local entrepreneurs belonging to the Zielony complementary currency system (which does not include domestic and foreign corporate entities with the same or similar product offerings). In this way, these entities generated between 3% and 6% of income per month from sales transactions in Zielony. The use of Zielony in payments for purchased products during the period under study was also due to its essential feature as a complementary currency: the realization of the function of means of payment, rather than a speculative and hoarding function.

The monthly turnover values of a selected deli-type store in Poland (between January 2019 and June 2021 in PLN and PLZ) presented in

Figure 6, which are similar in the pre-COVID-19 period and during the pandemic, show a similar trend to the results obtained by non-restricted grocery stores nationwide. As indicated by the results of the expert opinion on changes in consumer goods distribution channels resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic cf. [

63], retail sales were 9.0% lower in March 2020 than in the same period of 2019. However, retail sales growth was shown by units selling pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and orthopedic equipment (+8.8%), as well as food, beverages and tobacco products (+2.5%) [

63] (p. 3). According to the authors of the report, during the COVID-19 period, including the lockdown, the most advantageous situation was enjoyed by stores, including retail chains, which use multiple distribution channels and retailers who have built integrated omnichannel systems (which are characterized by harmonization of activities concerning, among others, delivering the product to the customer regardless of which channel he or she chooses). This situation also applies to small and micro stores selling groceries, e.g., because customers buy more and more frequently in smaller private stores and convenience-type stores belonging to franchise chains, and in response to the needs of customers who prioritize safety or shopping convenience, some micro stores have expanded their operations by accepting local orders by phone, e-mail or text message and delivering them to their houses. In addition, selected retail chains have prepared an offer of standard sets of basic grocery products in several options: collection in person or courier delivery [

63] (pp. 9–11).

Summing up, as, in the case of state money, the circulation of complementary currency in the local economy is also extremely important for the development of entities that belong to the complementary currency system. The Zielony currency supplements the shortage of state money and allows for the realization of transactions at the level of basic needs (one could say that it supports bottom-up economic activity, i.e., the functioning of entities primarily of a service nature, i.e., micro-, small- and medium-sized entities within the B2C relations (i.e., hairdressers, beauty salons, bakeries, confectioneries, guesthouses, hotels, motels, car repair shops, etc.), which struggle with various systemic and administrative difficulties, competition from larger entities, foreign concerns and corporations, etc.

The research results show how the complementary currency Zielony responds to changes in the economy, especially in a situation of emergency, crisis, etc., having a non-financial background (e.g., lockdown). As shown in previous studies, the first and second lockdowns, bans and trade restrictions especially affected those industries and entities on which these restrictions were imposed. The complete prohibition of economic activity during the described periods meant that service providers who have joined the system of complementary currencies could not use the Zielony (including the Polish zloty) for payments, as they had to completely cease their service activities during the periods in question. As a result, the entities belonging to the system of complementary currencies did not put Zielony into circulation; thus, it was excluded from the circulation process in the local economy. Additionally, the main function of complementary currencies is precisely the payment function and its rapid circulation.

The example of restaurant X, which has joined the Zielony complementary currency system, used in the article shows that the lockdown situation during the COVID-19 pandemic period, and with it other restrictions resulting from it, block/suspend the activity of the entity for a certain period of time and thus prevent the use of Zielony in both bottom-up (B2C) and business (B2B) transactions. This dependency applies to about 80% of service entities in the local economy that have joined the Zielony currency system in Poland.

In the case of entities that used the Zielony currency in settlements in Poland and were not subject to restrictions and lockdown during the COVID-19 period under study (i.e., trading and manufacturing entities comprising about 20% of the group that makes up the Zielony currency system), the value of the turnover they achieved remained almost unchanged relative to the turnover they achieved before the pandemic. An example illustrating this relationship was the Y deli-type store mentioned in the article.

The statistical analysis and the results of the expert interview presented in the paper made it possible to realize the main objective and specific objectives of the study. The realization of the objectives enabled the authors to formulate the following conclusions and relationships:

There are significant differences in the number of transactions expressed in Zielony and the volume of turnover in Zielony in the period before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in entities that have joined the analyzed complementary currency system;

The impact of the COVID-19 lockdown and restrictions on the functioning of the system and the circulation of Zielony during the COVID-19 period depends, among other things, on the types of entities on which restrictions and lockdowns were imposed by the government and on the structure of the system, i.e., the percentage of service, trading and manufacturing entities making up the system. The results of the analysis conducted show that:

- ○

During the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown period, the lowest demand for the complementary currency Zielony in Poland was recorded with respect to local service companies that are participants in the system;

- ○

Trading and manufacturing entities that are part of Zielony complementary currency system on which lockdown and other restrictions have not been imposed have not experienced significant declines in the number of transactions conducted using Zielony and the value of sales turnover using Zielony;

There is a close and unidirectional correlation between the value of transactions carried out using Zielony by entities operating in the complementary currency system and the value of transactions carried out by all entities in the Świętokrzyskie Province and in Poland in the national currency, PLN, during the lockdown and COVID-19 pandemic.

In summary, complementary currency Zielony in Poland is not very supportive of strengthening the situation of entities in the local economy during the economic crisis of epidemiological origin (i.e., COVID-19, including lockdown). This is primarily due to administrative and legal conditions that limit (inhibit) the development of local B2B and B2C businesses, especially those with a service profile.

Building the Zielony complementary currency system requires a concerted effort to build a sustainable future. The Zielony complementary currency can support sustainable development by influencing people’s needs without compromising future generations’ ability to meet their own needs. The growing popularity of the Zielony, as well as the recognition of the benefits of using an analyzed complementary currency in local communities, can help shape conditions that are important for sustainable development.

7. Conclusions

All compensation and complementary money systems are local in nature. They have regulations that inhibit the outflow of these means of settlement outside the region, country, etc., in which they are used. Complementary currencies function side by side with the state money and make up for its shortage (it is postulated that these two systems are used in parallel, just as in local communities Switzerland, Belgium, Spain, Denmark, the United States, Japan, Canada, Mexico, Uruguay, Greece, Jamaica, Argentina, the United Kingdom, the Republic of Bashkiria and other countries).

Complementary currencies are based on cooperation and transaction functions. They are considered a global phenomenon. Complementary currencies are also seen as a tool of so-called “economic patriotism”, especially in Western European countries. They protect against the negative effects of financial crises and take the initiative of local financial systems.

Joining the Zielony complementary currency system by various economic entities is voluntary. Entities that have joined the system use payments in Zielony as a complementary form to payments received and/or realized in the national currency (the example of a deli-store mentioned in the paper indicates that revenues obtained using Zielony represent 3–6% of the total value of revenues of this store. The rest of the revenue is generated in PLN). The motives for joining the complementary currency system may vary from economic to political or social.

The main objective of the paper, i.e., to present the impact of the lockdown and the COVID-19 pandemic on the functioning and circulation of complementary currencies in service, trade and manufacturing entities that have joined the Zielony complementary currency system in Poland, has been realized.

The specific objectives adopted in the research process have also been realized: the number of transactions expressed in Zielony currency and the volume of turnover in Zielony currency in entities that have joined the analyzed system of complementary currency in the period before and during the COVID-19 pandemic were determined; it was indicated how COVID-19 restrictions and their reference to the type of economic activity of the entity (i.e., service, trade, production) affect the functioning of the system and the circulation of the complementary currency Zielony in the period of COVID-19; the correlation between the value of transactions carried out by entities using the complementary currency Zielony and the value of transactions executed by all entities in the Świętokrzyskie Province and in Poland in the national currency, PLN, in the period of the lockdown and the COVID-19 pandemic was shown. These objectives were achieved through, among other things, statistical analysis, including the presented data on the value of turnover expressed in Zielony, obtained by the mentioned service, trade and production entities in 2015–2021, and the number of transactions realized by these entities in the corresponding period.

The authors have also solved the main research problem concerning the impact of lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic on the use of Zielony in commercial transactions by entities belonging to the local currency system in Poland. As it results from the conducted literature research, statistical research, results of the expert interview and results of reality observation, lockdown blocks the functioning and activity of the restricted entities and thus inhibits the circulation of Zielony currency in the entities forming the system and in the economy.

The thesis put forward by the authors, expressed in the form of a formulation that the complementary currency Zielony in Poland is not a tool that would support the functioning of entities (among others in the local economy) during a crisis of a non-financial nature (i.e., such as the COVID-19 pandemic), on which lockdown and other restrictions were imposed, was confirmed. As the conducted analysis shows, during the lockdown period, service entities belonging to the system, covered by pandemic restrictions, did not have any impact on the creation and circulation of the Zielony in the local economy and thus did not generate any revenue obtained both in Polish zloty and Zielony. Commercial enterprises, on the other hand, were just the opposite.

Complementary currencies have a significant impact on the functioning and development of local economic entities: they contribute to increasing the process of their debt relief, increasing the revenues and profits obtained by them and building an efficient cash flow of local enterprises that have joined the system. The progressive monopolization of the market and the increasing role of multinational corporations significantly affect the activities of micro-, small- and medium-sized local enterprises, which are important for the functioning of the system of complementary currencies, including Zielony. Corporatization of the economy leads to a decrease in the activity of local entities in the market and thus negatively affects the development of the complementary currency system.

A significant constraint for the smooth circulation and development of the system of complementary currency Zielony in the local economy is lockdown and legal restrictions imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic, which to various degrees affect the participants—customers of the structure of the analyzed complementary currency. Taking into account the characteristics of complementary currencies (including the complementary currency Zielony), among others, the need for circulation in the economy, as means of payment, the above-mentioned restrictions result in the necessity of partial or full cessation of economic activity by micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises that:

Joined the system of complementary currency;

Operate in the local market, especially in the service sector (hotels, tourism and restaurants, hairdressing, cosmetics, etc.);

As a result of the cessation of business activity during the lockdown are not able to receive income and profits.

In conclusion, the complementary currency Zielony in Poland during lockdown is not a tool to support the functioning and development of the entities subject to restrictions and lockdown in the local economy during the COVID-19 pandemic. The absence and/or fragmentation of economic activity of entities in various industries and sectors of the local economy affected by the lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic make complementary currencies, including Zielony, less (or not at all) used in payment transactions by economic entities participating in the system, remaining outside the economic and financial circulation and contributing little to their development during the period under study. Polish Local Currency Zielony is conducive to the creation of local entrepreneurship, including the development and financing of micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises primarily in the period without lockdown and administrative restrictions limiting trade in local products and services, and especially in the period of financial crises, when it can be used as a tool for debt relief, financing and supplementing the shortage of national currency in the local market.

The future of the complementary currency Zielony in Poland depends on the global pandemic situation in the coming months/years and state actions related to lockdown and other restrictions on the activities of entities. According to the optimistic scenario, the authors assume that the COVID-19 pandemic will end in 2021 or in the first half of 2022, and the complementary currency Zielony will be available to all service, trading and manufacturing entities belonging to the system without lockdown restrictions. The optimistic scenario also assumes that new entities and individuals will join the system and that system participants will achieve a number of transactions and turnover values that are similar to or higher than their pre-pandemic performance.

In the pessimistic scenario, the authors assume the persistence of the COVID-19 pandemic over the next few years, along with subsequent lockdowns and other restrictions on the activities of all or most of the service, trading and manufacturing entities that make up the Zielony currency system. Subsequent lockdowns will result in difficulties in the circulation of the complementary currency Zielony in the economy, a decrease in the number of transactions and the value of turnover of the entities using the analyzed currency and, as a consequence, difficulties in attracting new participants to the system, financial and organizational problems of the system, and eventually its collapse or suspension of activities.

The optimal scenario takes into account the end of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2022 or 2023, lifting of lockdown and other blockades limiting the functioning of the system of complementary currency and consequently, restored possibility of using the analyzed currency by entities covered by the lockdown during the pandemic. The dynamics with which new entities and individuals will join the system may be higher than before the pandemic because these entities will be oriented on obtaining an additional source of financing, rebuilding their position in the local market, gaining or maintaining a competitive advantage, etc. Experience with the impact of lockdown on the circulation of Zielony in the group of entities subject to pandemic restrictions will result in a change in the strategy for the development of the Zielony complementary currency system in subsequent years, including activities taken up by the system administrator, which will result in actions aimed at attracting new participants to the system who are primarily involved in trading and production activities (an expected increase from the current 20% of all system participants to 50%) and to a lesser extent, service activities (expected decrease from 80% of all system participants to 50%). This could ensure greater circulation of Zielony in the economy in periods associated with, for example, periodic economic fluctuations, a crisis or another pandemic combined with a lockdown.

To sum up, Zielony—Polish Local Currency is beneficial to the promotion of sustainable development, contributes to strengthening the economic position of entities in the region and has a significant impact on the monetary policy of entities in the local economy. According to the authors, the aforementioned benefits are obtained by the entities belonging to the complementary currency system in the local economy, but not during the lockdown and COVID-19 pandemic.