Determinants of Sustainable Open Innovations—A Firm-Level Capacity Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

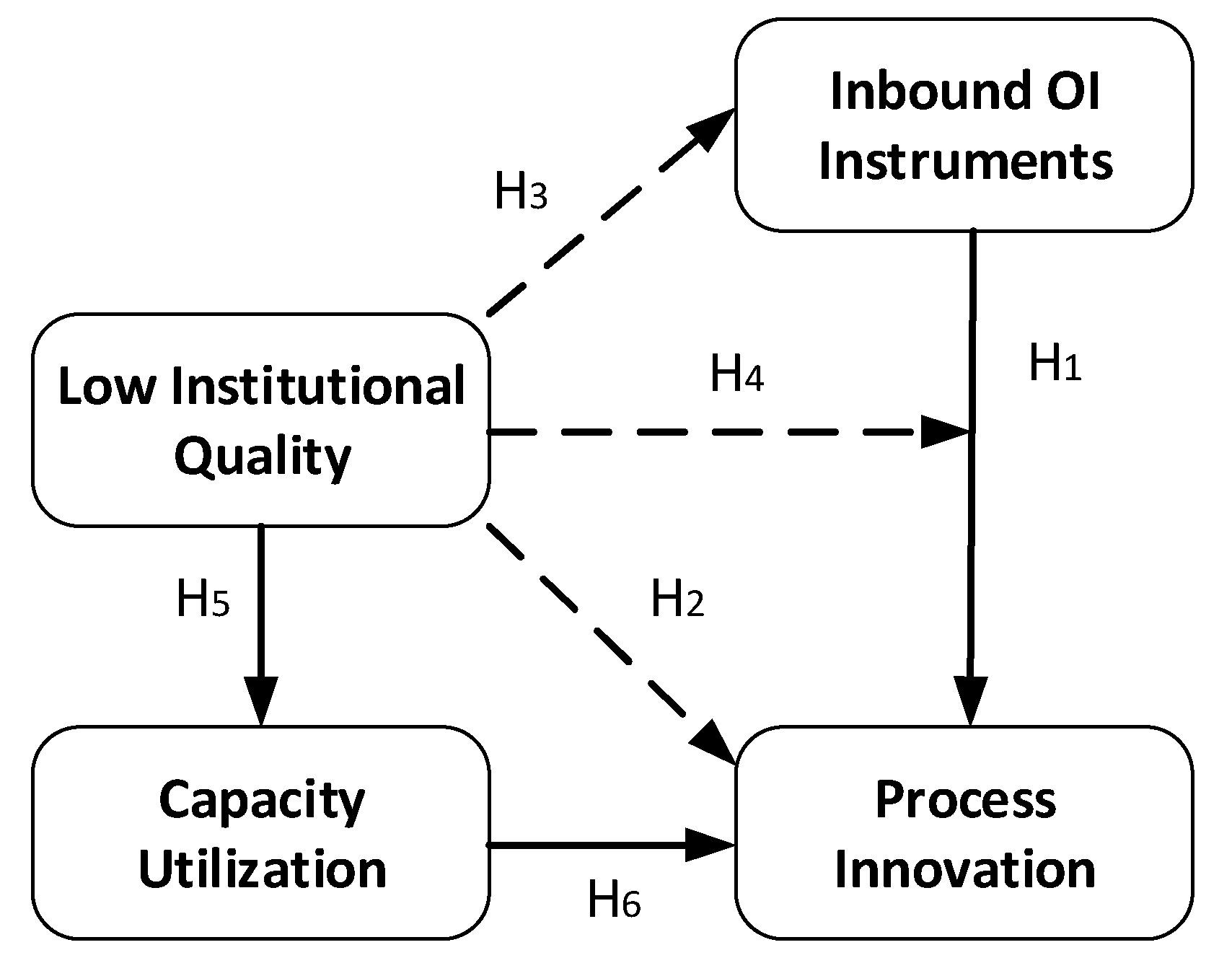

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Inbound Open Innovation Instruments as Predictors of Firms’ Innovation

2.2. Institutional Quality Indicators and Their Role in Enhancing Firms’ Innovation

2.3. Influence of Institutional Quality on Firm Openness

2.4. Institutional Quality, Capacity Utilization, and Firm Innovation Performance

3. Research Methodology and Data

4. Results

4.1. Model Evaluation

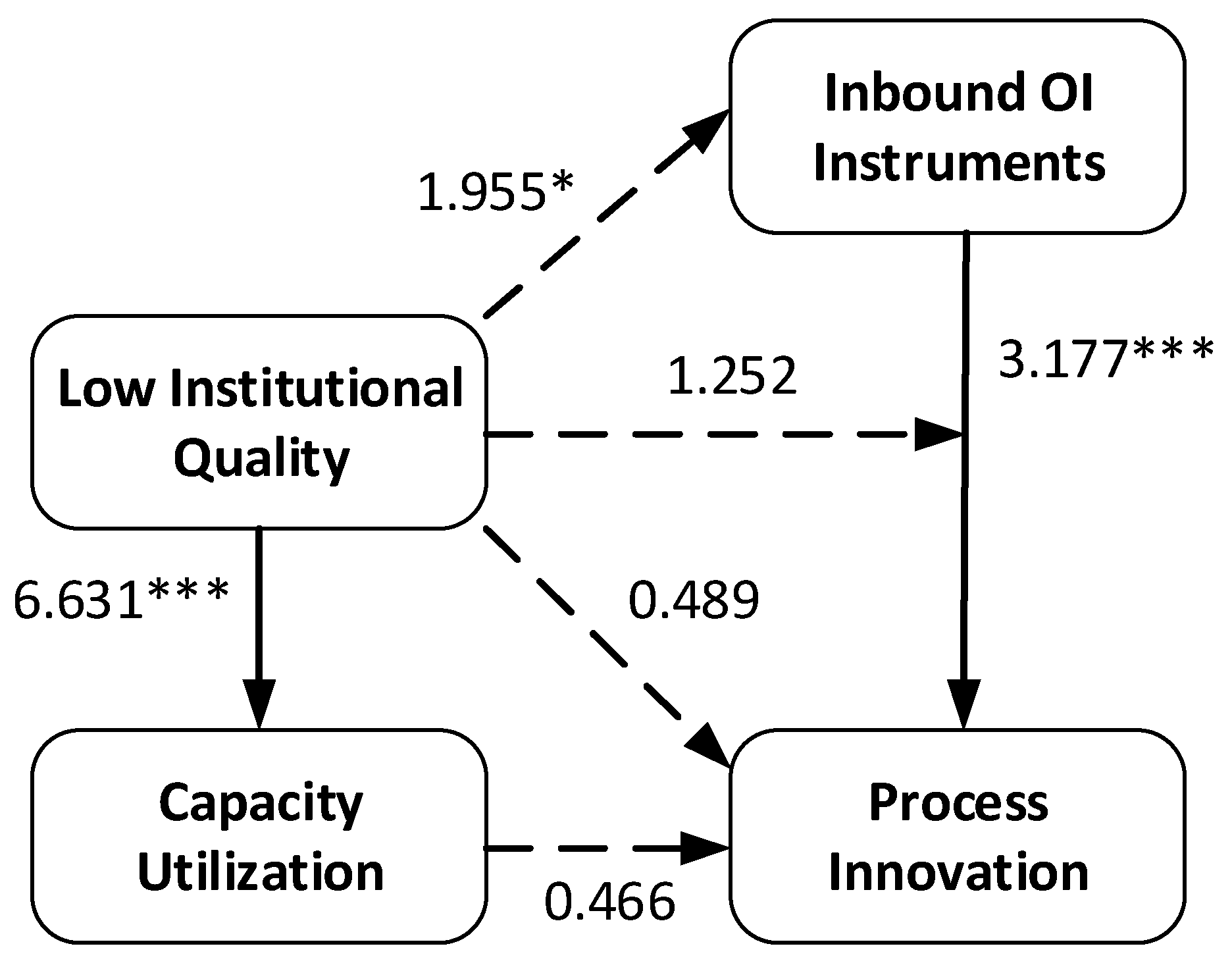

4.2. Analysis of Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Discussion of Obtained Results

5.2. Theoretical and Practical Contributions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Spithoven, A.; Clarysse, B.; Knockaert, M. Building absorptive capacity to organise inbound open innovation in traditional industries. Technovation 2010, 30, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqshbandi, M.M.; Tabche, I.; Choudhary, N. Managing open innovation. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 703–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliasghar, O.; Rose, E.L.; Chetty, S. Where to search for process innovations? The mediating role of absorptive capacity and its impact on process innovation. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 82, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinthal, D.; March, J.G. A model of adaptive organizational search. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1981, 2, 307–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, K.; Salter, A. Open for innovation: The role of openness in explaining innovation performance among UK manufacturing firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres de Oliveira, R.; Verreynne, M.L.; Figueira, S.; Indulska, M.; Steen, J. How do institutional innovation systems affect open innovation? J. Small Bus. Manag. 2020, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunov, C. Corruption’s asymmetric impacts on firm innovation. J. Dev. Econ. 2016, 118, 216–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Yano, G. How does anti-corruption affect corporate innovation? Evidence from recent anti-corruption efforts in China. J. Comp. Econ. 2017, 45, 498–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.K.; Nelson, M.A. Capacity utilization in emerging economy firms: Some new insights related to the role of infrastructure and institutions. Q. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2020, 76, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solow, R.M. Technical change and the aggregate production function. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1957, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Romer, P.M. Increasing returns and long-run growth. J. Political Econ. 1986, 94, 1002–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aghion, P. Entrepreneurship and growth: Lessons from an intellectual journey. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 48, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumol, W.J. Formal entrepreneurship theory in economics: Existence and bounds. J. Bus. Ventur. 1993, 8, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekana, D.M. Innovation and Economic Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa: Why Institutions Matter? An Empirical Study across 37 Countries. Arthaniti J. Econ. Theory Pract. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussen, M.S.; Çokgezen, M. The impact of regional institutional quality on firm innovation: Evidence from Africa. Innov. Dev. 2021, 11, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baris, S. Innovation and institutional quality: Evidence from OECD countries. Glob. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. Curr. Issues 2019, 9, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barasa, L.; Knoben, J.; Vermeulen, P.; Kimuyu, P.; Kinyanjui, B. Institutions, resources and innovation in East Africa: A firm level approach. Res. Policy 2017, 46, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunyi, A.A.; Agyei-Boapeah, H.; Areneke, G.; Agyemang, J. Internal capabilities, national governance and performance in African firms. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2019, 50, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LiPuma, J.A.; Newbert, S.L.; Doh, J.P. The effect of institutional quality on firm export performance in emerging economies: A contingency model of firm age and size. Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 40, 817–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Idrissi, N.E.A.; Ilham Zerrouk, I.; Zirari, N.; Monni, S. Comparative study between two innovative clusters in Morocco and Italy. Insights Reg. Dev. 2020, 2, 400–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casadella, V.; Younes Bouacida, R. The primacy of innovation capacities in the NIS of the Maghreb countries: An analysis in terms of learning capacity in Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria. Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. Dev. 2020, 12, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le HT, T.; Dao QT, M.; Pham, V.C.; Tran, D.T. Global trend of open innovation research: A bibliometric analysis. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2019, 6, 1633808. [Google Scholar]

- Zhylinska, O.; Bazhenova, O.; Zatonatska, T.; Dluhopolskyi, V.; Bedianashvili, G.; Chornodid, I. Innovation Processes and Economic Growth in the Context of European Integration. Sci. Pap. Univ. Pardubic. Ser. D Fac. Econ. Adm. 2020, 28, 1209. [Google Scholar]

- Stejskal, J.; Hájek, P.; Prokop, V. Collaboration and innovation models in information and communication creative industries—The case of Germany. J. Inf. Commun. Technol. 2018, 17, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Prokop, V.; Stejskal, J.; Klimova, V.; Zitek, V. The role of foreign technologies and R&D in innovation processes within catching-up CEE countries. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250307. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriele Arnold, M. The role of open innovation in strengthening corporate responsibility. Int. J. Sustain. Econ. 2011, 3, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Medeiros, J.F.; Ribeiro, J.L.D.; Cortimiglia, M.N. Success factors for environmentally sustainable product innovation: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Hermosilla, J.; Del Río, P.; Könnölä, T. Diversity of eco-innovations: Reflections from selected case studies. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1073–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisodiya, S.R.; Johnson, J.L.; Grégoire, Y. Inbound open innovation for enhanced performance: Enablers and opportunities. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2013, 42, 836–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li-Ying, J.; Mothe, C.; Nguyen, T.T.U. Linking forms of inbound open innovation to a driver-based typology of environmental innovation: Evidence from French manufacturing firms. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 135, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prokop, V.; Stejskal, J. Determinants of innovation activities and SME absorption—Case study of Germany. Sci. Pap. Univ. Pardubic. Ser. D Fac. Econ. Adm. 2019, 46, 134–146. [Google Scholar]

- Akinwale, Y.O. Empirical analysis of inbound open innovation and small and medium-sized enterprises’ performance: Evidence from oil and gas industry. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2018, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduro, S. Examining open innovation practices in low-tech SMEs: Insights from an emerging market. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2019, 10, 509–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan, S.; Bierly, P.; Kessler, E.H. A reexamination of product and process innovations using a knowledge-based view. J. High. Technol. Manag. Res. 1999, 1, 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.; Lee, J.H.; Garrett, T.C. Synergy effects of innovation on firm performance. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 99, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugo, P.C.; Namada, J.M. Process Innovation and Competitive Advantage in Telecommunication Companies. Int. J. Bus. Strategy Autom. (IJBSA) 2020, 1, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, K.H.; Wang, J.C. External technology sourcing and innovation performance in LMT sectors: An analysis based on the Taiwanese Technological Innovation Survey. Res. Policy 2009, 38, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Padua Pieroni, M.; McAloone, T.; Pigosso, D. Business model innovation for circular economy: Integrating literature and practice into a conceptual process model. In Proceedings of the Design Society: International Conference on Engineering Design, Delft, The Netherlands, 5–8 August 2019; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, July 2019; Volume 1, pp. 2517–2526. [Google Scholar]

- Rauter, R.; Globocnik, D.; Perl-Vorbach, E.; Baumgartner, R.J. Open innovation and its effects on economic and sustainability innovation performance. J. Innov. Knowl. 2019, 4, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valenteová, K.; Čukanová, M.; Steinhauser, D.; Sidor, J. Impact of institutional enviroment on the existence of fast-growing business in time of economic disturbances. Sci. Pap. Univ. Pardubic. Ser. D Fac. Econ. Adm. 2018, 43, 926. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, S.W.; McMullen, J.S.; Artz, K.; Simiyu, E.M. Capital is not enough: Innovation in developing economies. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 684–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidochukwu Obi, C.; Ifelunini, I. Mobilization of domestic resources for economic development financing in Nigeria: Does tax matter? Sci. Pap. Univ. Pardubic. Ser. D Fac. Econ. Adm. 2019, 45, 113–125. [Google Scholar]

- Roxas, B.; Chadee, D.; Erwee, R. Effects of rule of law on firm performance in South Africa. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2012, 24, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, Y.; Wittmann, X.; Peng, M.W. Institution-based barriers to innovation in SMEs in China. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2012, 29, 1131–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, J.A.; Garcimartín, C. The determinants of institutional quality. More on the debate J. Int. Dev. 2013, 25, 206–226. [Google Scholar]

- Gribnau JL, M. The Integrity of the Tax System after BEPS: A Shared Responsibility. Erasmus Law Rev. 2017, 10, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ndinga-Kanga, M.; van der Merwe, H.; Hartford, D. Forging a Resilient Social Contract in South Africa: States and Societies Sustaining Peace in the Post-Apartheid Era. J. Interv. State Build. 2020, 14, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puffer, S.M.; McCarthy, D.J.; Boisot, M. Entrepreneurship in Russia and China: The impact of formal institutional voids. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2010, 34, 441–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadee, D.; Roxas, B. Institutional environment, innovation capacity and firm performance in Russia. Crit. Perspect. Int. Bus. 2013, 9, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, X. Corruption culture and corporate misconduct. J. Financ. Econ. 2016, 122, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeume, S. Bribes and firm value. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2017, 30, 1457–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toleikienė, R.; Balčiūnas, S.; Juknevičienė, V. Youth Attitudes Towards Intolerance to Corruption in Lithuania. Sci. Pap. Univ. Pardubic. Ser. D Fac. Econ. Adm. 2020, 28, 109. [Google Scholar]

- Heo, Y.; Hou, F.; Park, S.G. Does corruption grease or sand the wheels of investment or innovation? Different effects in advanced and emerging economies. Appl. Econ. 2020, 53, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breen, M.; Gillanders, R. Corruption, institutions and regulation. Econ. Gov. 2012, 13, 263–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Achelhi, H.; Narjisse, L.; Mustapha, B.; Patrick, T. Barriers to innovation in Morocco: The Case of Tangier & Tetouan Region. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Res. 2016, 2, 592–612. [Google Scholar]

- Barone, E.; Ranamagar, N.; Solomon, J.F. A Habermasian model of stakeholder (non) engagement and corporate (ir) responsibility reporting. Account. Forum 2013, 37, 163–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Loh, L.; Wu, W. How do Environmental, Social and Governance Initiatives Affect Innovative Performance for Corporate Sustainability? Sustainability 2020, 12, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, D.; Wang, A.X.; Zhou, K.Z.; Jiang, W. Environmental strategy, institutional force, and innovation capability: A managerial cognition perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 1147–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrone, P.; Grilli, L.; Mrkajic, B. The role of institutional pressures in the introduction of energy-efficiency innovations. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1245–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafouros, M.; Wang, C.; Piperopoulos, P.; Zhang, M. Academic collaborations and firm innovation performance in China: The role of region-specific institutions. Res. Policy 2015, 44, 803–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clarke, G.R. Firm Registration and Bribes: Results from a Microenterprise Survey in Africa. In Proceedings of the 19th Annual Western Hemispheric Trade Conference, Laredo, TX, USA, 15–17 April 2015; p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Buehn, A.; Schneider, F. Corruption and the shadow economy: Like oil and vinegar, like water and fire? Int. Tax Public Financ. 2012, 19, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdiev, A.N.; Goel, R.K.; Saunoris, J.W. Corruption and the shadow economy: One-way or two-way street? World Econ. 2018, 41, 3221–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Howard, M.C.; Nitzl, C. Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawojska, A. Determinants of farmers’ trust in government agricultural agencies in Poland. Agric. Econ. 2010, 56, 266–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gyamfi, S.; Stejskal, J. Cooperating for knowledge and innovation performance: The case of selected Central and Eastern European countries. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2021, 18, 264. [Google Scholar]

- Prokop, V.; Stejskal, J.; Hajek, P. The influence of financial sourcing and collaboration on innovative company performance: A comparison of Czech, Slovak, Estonian, Lithuanian, Romanian, Croatian, Slovenian, and Hungarian case studies. In Knowledge Spillovers in Regional Innovation Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 219–252. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.C.; Wang, C.W.; Ho, S.J. Country governance, corruption, and the likelihood of firms’ innovation. Econ. Model. 2020, 92, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, G.; Sarstedt, M. Heuristics versus statistics in discriminant validity testing: A comparison of four procedures. Internet Res. 2019, 29, 430–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, J.H.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Ramayah, T.; Ting, H. Convergent validity assessment of formatively measured constructs in PLS-SEM: On using single-item versus multi-item measures in redundancy analyses. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 11, 3192–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent and asymptotically normal PLS estimators for linear structural equations. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2015, 81, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henseler, J.; Dijkstra, T.K.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Straub, D.W.; Calantone, R.J. Common beliefs and reality about PLS: Comments on Rönkkö and Evermann (2013). Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 17, 182–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheng, C.C.; Shiu, E.C. The inconvenient truth of the relationship between open innovation activities and innovation performance. Manag. Decis. 2015, 53, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keupp, M.M.; Gassmann, O. Determinants and archetype users of open innovation. RD Manag. 2009, 39, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parida, V.; Westerberg, M.; Frishammar, J. Inbound open innovation activities in high-tech SMEs: The impact on innovation performance. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2012, 50, 283–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Terjesen, S.; Patel, P.C. In search of process innovations: The role of search depth, search breadth, and the industry environment. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 1421–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.W. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Z.; Liu, J.; Li, L.; Gu, X. The effect of environmental regulation on capacity utilization in China’s manufacturing industry. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Zhang, M. The cost of weak institutions for innovation in China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 153, 119937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prokop, V.; Hajek, P.; Stejskal, J. Configuration Paths to Efficient National Innovation Ecosystems. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 168, 120787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogers, M.; Zobel, A.K.; Afuah, A.; Almirall, E.; Brunswicker, S.; Dahlander, L.; Ter Wal, A.L. The open innovation research landscape: Established perspectives and emerging themes across different levels of analysis. Ind. Innov. 2017, 24, 8–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.J.; Liu, Z. Micro-and Macro-Dynamics of Open Innovation with a Quadruple-Helix Model. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Latent Variable/Construct | Manifest Variable | Description | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| INBOUND-OI (Inbound Open Innovation) | I-OI_1 | Over the last three years, did this establishment spend on the acquisition of external knowledge? This includes the purchase or licensing of patents and non-patented inventions, know-how, and other types of knowledge from other businesses or organizations. | [30,68] |

| I-OI_2 | Over the last three years, did this establishment spend on research and development activities contracted with other companies? | ||

| I-OI_3 | In fiscal year, did this establishment purchase or acquire any trademarks, copyrights, patents, licenses, service contracts, franchise agreements, or other intangible assets? | ||

| CAP-UTIL (Capacity Utilization) | CAP_UTIL-1 | Capacity utilization. | [9] |

| CAP_UTIL-2 | Firm operating hours. | ||

| LOW INST.QUAL (Low Institutional Quality) | INST.QUAL 1 | The degree to which the tax rate is obstacle to firm operation. | [50] |

| INST.QUAL 2 | The degree to which the tax administration is obstacle to firm operation. | [19] | |

| INST.QUAL 3 | The degree to which business licensing and permit is obstacle to firm operation. | [7] | |

| INST.QUAL 4 | The degree to which political instability is obstacle to firm operation. | ||

| INST.QUAL 5 | The degree to which corruption is obstacle to firm operation. | [69] | |

| INST.QUAL 6 | The degree to which the court system is obstacle to firm operation. | [6] | |

| FIRM-INNOV (Process Innovation) | ProcINN | Introduction of new or improved process. | [3] |

| CONTROLS | C1 | Number of permanent full-time workers. | [9] |

| Variable | VIF |

|---|---|

| I-OI_1 | 1.496 |

| I-OI_2 | 1.423 |

| I-OI_3 | 1.409 |

| CAP_UTIL-1 | 1.918 |

| CAP_UTIL-2 | 1.987 |

| LOW INST.QUAL 1 | 1.000 |

| LOW INST.QUAL 2 | 2.122 |

| LOW INST.QUAL 3 | 1.888 |

| LOW INST.QUAL 4 | 1.000 |

| LOW INST.QUAL 5 | 2.106 |

| LOW INST.QUAL 6 | 1.818 |

| I-OI_1 | 1.174 |

| I-OI_2 | 1.174 |

| C1 | 1.000 |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Rho_Alpha | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAP-UTIL | 0.556 | 0.601 | 0.814 | 0.687 |

| INBOUND-OI | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| FIRM-INNOV | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| LOW INST.QUAL | 0.881 | 0.896 | 0.909 | 0.625 |

| CONTROLS | 0.730 | 0.735 | 0.847 | 0.648 |

| MODERATING EFFECT | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Saturated Model | Unsaturated Model | |

|---|---|---|

| SRMR | 0.058 | 0.059 |

| dULS | 0.311 | 0.314 |

| dG | 0.114 | 0.115 |

| Chi-Square | 785.542 | 789.487 |

| NFI | 0.806 | 0.805 |

| Construct Path | Loading | T Stats. | p Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| INBOUND−OI => FIRM−INNOV (H1) | 0.172 | 3.177 | 0.002 *** |

| INST.QUAL => FIRM−INNOV (H2) | −0.016 | 0.489 | 0.625 |

| LOW INST.QUAL => INBOUND−OI (H3) | −0.056 | 1.955 | 0.051 * |

| LOW INST.QUALME => FIRM−INNOV (H4) | −0.084 | 1.252 | 0.211 |

| LOW INST.QUAL => CAP−UTIL (H5) | 0.184 | 6.631 | 0.000 *** |

| CAP−UTIL => FIRM−INNOV (H6) | −0.013 | 0.466 | 0.641 |

| CONTROLS => FIRM−INNOV | −0.029 | 2.634 | 0.009 *** |

| Hypotheses | Decision |

|---|---|

| H1: Implementation of inbound OI instruments of manufacturing firms in Morocco has a positive and significant influence on firms’ process innovation. | Accepted |

| H2: Low Institutional quality negatively affect process innovation of manufacturing firms in Morocco. | Rejected |

| H3: Low Institutional quality of Morocco negatively affects manufacturing firms’ implementation of inbound OI instruments. | Accepted |

| H4: The relationship between the implementation of inbound OI instruments and firm’s innovation performance in Morocco is negatively moderated by low institutional quality. | Rejected |

| H5: There is a strong and positive significant effect of low institutional quality on manufacturing firms’ capacity utilization in Morocco. | Accepted |

| H6: There is a positive and significant relationship between firm’s capacity utilization and its process innovation. | Rejected |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gyamfi, S.; Sein, Y.Y. Determinants of Sustainable Open Innovations—A Firm-Level Capacity Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9088. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169088

Gyamfi S, Sein YY. Determinants of Sustainable Open Innovations—A Firm-Level Capacity Analysis. Sustainability. 2021; 13(16):9088. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169088

Chicago/Turabian StyleGyamfi, Solomon, and Yee Yee Sein. 2021. "Determinants of Sustainable Open Innovations—A Firm-Level Capacity Analysis" Sustainability 13, no. 16: 9088. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169088

APA StyleGyamfi, S., & Sein, Y. Y. (2021). Determinants of Sustainable Open Innovations—A Firm-Level Capacity Analysis. Sustainability, 13(16), 9088. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169088