1. Introduction

Teacher agency plays a critical role in sustaining early career teachers’ professional development. Teachers who are of proactive agency can stay true to themselves in seeking career development [

1]. Teachers who exercise proactive agency are more likely to regard themselves as a member of “a meaningful profession”, rather than doing “just a job” [

2] (p. 149). Teacher agency strengthens the teachers’ commitment to develop themselves as teachers. To provide implications for early career teachers’ professional development, it is essential to explore what shapes teachers’ enactment of agency, including resistance, ambivalence, and proactivity, and to examine the intricate relationship between teacher agency and identity commitment [

3].

Early career teachers’ professional development remains a global concern [

4,

5]. Despite the voluminous literature on teacher attrition, little attention is paid to teachers’ “lived experience”, underpinning their decisions to stay in or leave the field [

6]. Early career teachers are influenced by the complex contexts in which they are situated [

7]. Schaefer, Long, and Clandinin [

8] pointed out that early career teachers’ professional development is also influenced by individual characteristics, such as demographics, family characteristics, burnout susceptibility, and other psychological features. In recent years, an astonishing number of teachers have been reported to have quitted teaching within a few years after a teacher education program [

9,

10]. This trend has become more worrying as rates of teacher turnover are consistently higher than those of other professions [

11]. Corcoran [

12] attributed this phenomenon to the “transition shock” that teachers face between the ideal and actual realities of teaching (p. 19). The main reasons included “teachers’ socio-demographic features, their preparation, and the specific features of their work environment” [

13] (p. 22). The factors that militate against efforts to retain teachers also included “relatively poor remuneration and working conditions, low professional status within the broader community” [

14] (p. 869).

The present study focused on Joyce (pseudonym), a novice teacher in Hong Kong, to examine her struggles to stay in or opt out of the teaching profession. Following the call for longitudinal studies that contextualize and temporalize early career teachers’ experiences [

6], the study aimed to scrutinize Joyce’s long-term teaching experiences and uncover her perceptions of, and reactions to, various challenges and/or opportunities in the contextual realities. Through exploring the blossoming and wilting of her career development, this article may broaden the conceptual base of agency and identity in language teacher education. Based on Joyce’s early years of in-service teaching, the findings provide implications for how early career teachers can be better prepared to stay in the profession, and how teacher agency and identity commitment can influence their professional development. The central research questions that guided the current study were as follows:

- (1)

How did the ESL teacher exercise her teacher agency to construct her professional identity during the early years of her teaching career?

- (2)

What influenced the ESL teacher’s decision to stay in or leave the teaching profession during the early years of her teaching career?

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

This study employs a longitudinal qualitative case study approach, drawing on narrative data. An exploration of people’s narratives allows us to understand their experiences that shape their personal and professional identities [

38]. Narrative inquiry is a powerful research method that can explore individuals’ personal life and practice in the community [

39]. Given the disadvantage of only one single case, the researcher attempted to dig deep into the participant’s long-term experiences. This longitudinal study could help us map into a teacher’s lived stories of joining the teaching profession after graduation from a teacher education program, serving three schools at three locations within six years, quitting teaching in her third school (in her sixth year of in-service teaching), and later feeling confused about resuming teaching or permanently leaving the profession.

3.2. Context and the Case Study Participant

Joyce entered the teaching profession in summer 2013, upon graduation from a BA and BEd English double degree program in Hong Kong. The author was her instructor and came to know her before the study started. Joyce was selected because she was a typical case who aspired to be an innovative teacher, but encountered various difficulties from her first year teaching. This study examined Joyce’s teaching and life experiences spanning over seven–eight years, from August 2013 to December 2020. Of particular emphasis was how she exercised her professional agency to construct her professional identity, and how her agency and identity work affected her intentions to stay in or leave the profession. Joyce volunteered to share her lived stories and she was guaranteed anonymity to avoid negative repercussions due to her participation. Before the study started, ethical approval was granted by the Research Committee of the University where the author was working.

Joyce served her first school during 2013–2014. She left this school after teaching only one year due to geographical distance and perceived lack of opportunities for professional learning. She served her second school during 2014–2016, where she maintained harmonious relationship with colleagues and benefited from collaboration among colleagues. She left the school due to funding unavailability. She joined a two-year part-time MEd program (2016–2018) for “a break” from full-time engagements, while taking temporary substitute-teacher positions in a few secondary schools. She secured a teaching position in a prestigious school (her third school), and resumed full-time teaching from September 2018. Triggered by an “insulting” classroom revisiting, she resigned after working in this school for only a few months (in November–December 2018), and left the profession suffering from depression for some weeks.

After recovering from her “mental illness”, she worked in an NGO. The contract ended in November 2019 and she chose not to renew it. During the short period of time of working for the education-related organization, Joyce compared her experiences in working as a teacher and an administrator, and also explained how her career decision was shaped by family commitments (particularly taking care of her young daughter). Within a two-year period from early 2019 (when she had left her third school and was about to work in the NGO) to December 2020, the researcher had the opportunity to interview Joyce four times, focusing on how she had been struggling to make a decision to resume or quit teaching.

3.3. Data Collection

This study employed longitudinal data collected with Joyce over seven–eight years. During this period of more than seven years, the researcher interviewed her eight times face-to-face, aiming to hear her lived stories from the point she entered the teaching profession to the moment of writing this paper. Each interview lasted more than one hour, and with Joyce’s prior consent, was audio-recorded. Other data sources included Joyce’s learning-English and learning-to-teach-English autobiography submitted to the author in 2012 as an undergraduate course assignment, informal conversations and WhatsApp/email communications with Joyce maintained by one of the researchers (i.e., one of the author’s senior research assistants who had established a rapport with Joyce over the years). The multiple sources of data triangulated with each other, enabling us to obtain a full picture of her experience and development over the whole period of seven–eight years.

3.4. Data Analysis

Data analysis and interpretation occurred over several stages along with data collection and the move from field to research texts. Data interpretation consisted of three main stages.

First, the researcher and his two senior research assistants carefully reviewed and coded the interview transcripts and other qualitative data, with particular attention paid to the enactment of teacher agency and the development of teacher identity.

Second, the researchers sought reasons or factors underlying Joyce’s decisions to leave or stay in the teaching profession. The researchers then continued data analysis with rigorous discussions and critical interpretations. The constructed narratives were shared with Joyce for further additions, amendments, and clarifications. For example, among the comments she left on our narrative draft (“Joyce’s Narrative”), she pointed out that some wordings about the geographical information of the three schools might reveal her identity. We thus removed such possibly sensitive information from the narrative draft. From Joyce’s written feedback and our conversations with her in member checking, we found that she was reluctant to quit teaching and leave the profession permanently. Therefore, such a process not only ensured the trustworthiness of data analysis, but also elicited more information through further elaboration of stories [

39].

Finally, we re-examined the themes in depth through rereading the data and composing mini-stories focusing on specific times, spaces, and characters involved. We deconstructed, constructed, and reconstructed the social meanings through writing mini-stories that referenced the identified themes. We selected excerpts from Joyce’s narratives to illustrate the story threads.

4. Findings

4.1. Budding Teacher Identity before and upon Graduation from University

Joyce’s budding teacher identity could be demonstrated in the following two aspects: aiming to become an innovative teacher, and trying to build a rapport with the students.

I would encourage my students to speak English in class… I don’t like using drills, and asking students to write words in English and repeat after the teacher. I want to be a creative, innovative, and active teacher.

(interview, 31 August 2013)

Joyce’s budding teacher identity, as shown in this interview with her at the very beginning of her first year teaching, was also juxtaposed with the “traditional teachers” that she described in her autobiography. Joyce intended to distinguish herself from the traditional teachers, who were characterized by an excessive emphasis on pattern drills and repetition. Her desired teacher identity was a teacher who is creative and innovative, and who would encourage students to speak English.

Such a desired innovative teacher identity was therefore grounded in her previous schooling experiences. In her autobiography, Joyce described her secondary schooling as “cultural immersion”—meaning that she was exposed to various “cultural activities” and language was learned through “communication”. These positive experiences strengthened her desire to become an innovative English teacher. When Joyce was half way through her teacher education program, she was already excited about teaching, commenting “I am about to start an exciting part of my life”. Becoming a teacher with a good relationship with students was what she desired. In an interview at the beginning of her first year teaching, she said, “teachers are students’ friends because we are helping them to grow” (interview, 31 August 2013). Such statements showed Joyce’s investment in teaching, which was to achieve a rapport with the students. She hoped to foster enthusiasm in her students, as shown by the following:

In becoming a secondary school teacher, I have started to think about various possibilities of my future career. … do my teachers and my experiences in secondary school influence me? I think to some extent yes. I hope secondary school students will be happy in learning English.

(interview, 31 August 2013)

It is clear that when the real teaching started, she was determined to bring some changes in her own classes. She shared her vision that secondary school students should be “happy in learning English”. The scenario symbolized the English learning environment that she wanted to create. She also perceived a need to inoculate value education into students, through informal chats, as outlined in the following: “to grow as a person involves the teaching or sharing of life values”. This approach was in good alignment with her broader beliefs that it is “an honor to help students grow” (interview, 31 August 2013).

In summary, Joyce’s teacher identity was formed through her prior learning experiences, her beliefs, her aspiration of becoming an ideal teacher, and her engagement in pedagogical innovations. Interpreted from Wenger’s [

23] idea of belonging, such process explains engagement and imagination functioning together, in shaping her teacher identity.

4.2. Negotiation between Determination and Realities in Serving Her First and Second Schools

Joyce started her teaching in her first secondary school, with anticipated challenges, such as workload, communication with parents, and students’ discipline problems. However, part of these worries dispersed after she started her job. She mentioned that “the school was supportive in developing a computer system for teachers to share materials”, “the senior teachers took initiatives to offer help”, “the mentor provided guidance and help”, and “the school arranged co-planning meetings between colleagues”. She established a belief that “teachers are in the classroom to facilitate and help students”, and “teachers should be friends with students” (interview, 13 October 2013).

Perceiving various possibilities for classroom teaching and professional development, her commitment to creating a learner-centered classroom was guided by a strong belief, for which LaBoskey [

40] described as “passionate creed”. The passionate creed sustained her efforts in having her own class throughout her initial years of teaching, in her first and second schools.

Joyce enjoyed the first two months of teaching in her first school, because of “the small-class teaching environment and the friendly students” (interview, 13 October 2013). However, soon after the happy moment, many things did not “go right” for Joyce. While positioning herself as a friend to her students, Joyce felt that she was too “lenient” towards them. She had difficulties in “striking a balance between being a friend and at the same time being an authority”; she found it challenging to manage her students’ behaviors, especially when they might “take advantage of” her “kindness” and “take a step further to do whatever they want” (interview, 25 January 2014).

Students interrupted me during lessons, which made me feel very mad. During exams, they would come over and ask questions which I have repeated thousands of times in class. A teacher should be a classroom manager before being innovative, creative, reflective.

(interview, 25 January 2014)

The above quote shows Joyce’s vulnerability to classroom management. Her determination to be a “caring, innovative, creative, and reflective” teacher was shattered by the realities.

Joyce looked forward to collaborating with colleagues and having professional learning opportunities. However, her first school was a young school, with young teachers and administrators who did not bond well with her. In an interview conducted five years after she left her first school, she said, “I didn’t feel the sense of connection even though we were not enemies” (interview, 6 April 2019). Joyce obviously wanted to learn from colleagues of different age ranges, and to become part of a professional teaching community. Disconnection with colleagues and tiredness of travelling a long distance for work, made her decide not to renew the contract with her first school.

Joyce joined her second school in September 2014. That school was in a closer proximity to her home. Fortunately, the “cultural ecology” [

17] (p. 202) of the school, characterized by what Joyce described as “ample collaboration opportunities and harmonious relationships among colleagues”, enabled her to be more agentic in some respects. Although her teaching was guided heavily by the scheme to work, she did not see it as a constraint on teaching and managed to find room to maneuver how she was delivering the content. For instance, she found that the students did not find the approach of teaching reading comprehension through examination questions useful in improving their reading skills. She realized that what she needed to teach were generic skills, which could empower her students to look for answers on their own.

Her two years at this school concluded in joy and satisfaction. Joyce was able to exert her teacher agency to take greater control over her teaching and her personal–professional development in her second school. Due to funding unavailability, and a desire for a break from full-time engagement, she left the school in August 2016.

4.3. Trapped into the Unknown in Serving Her Third School

After leaving her second school, Joyce decided to enroll in a two-year part-time MEd (ELT) program. When talking about her future after obtaining her MEd degree, she emphasized that more consideration would be given to “how much time I have left for my family members” (interview, 6 April 2019). However, she felt as though she should still attempt to take a full-time teaching job. She accepted an offer as a full-time English teacher at a prestigious secondary school (her third school), starting from September 2018.

Though it seemed a good offer, things did not go well when the term started. She was informed of the classes assigned to her only a few days before the commencement of the school year. She was assigned a senior form class that required advanced materials and careful preparation. She received little concrete support on the departmental and personal levels. No teaching materials were available. Verbal sharing among colleagues was also rare.

In her third school, surveillance mechanisms, such as homework inspection and lesson observation, were in place, as part of the “quality control” measures. In response to our invitation to member check “Joyce’s Narrative”, Joyce made the following track changes: “While these measures may be common in the field nowadays, the school she was in might do it repeatedly until the ‘bosses’ all felt satisfied”. However, meeting the requirements of all “bosses” (the principal, vice-principals, and the panel head) had never been an easy job. In most interviews with her after she left the school, during 2019–2020, she repeatedly mentioned these “abnormal” quality control measures in such a “depressing working environment”, particularly classroom revisits and rechecking of students’ assignments. Apart from those mechanisms, the principal of that school sometimes stood outside her classroom observing. She felt “offended”, as the following shows:

I have never experienced such a lesson observation. Some teachers observed my lessons and commented that I couldn’t live up to their standard. The principal stood at the door of my classroom for a long period of time without leaving, and I felt offended. I was also offended by a Chinese history teacher who evaluated my teaching, and I don’t see why this Chinese history teacher was qualified to judge how I teach English. I felt untrusted and disrespected.

(interview, 6 April 2019)

Joyce felt particularly “offended” because a Chinese history teacher evaluated and criticised her teaching. That lesson did not go well in the observers’ eyes and an avalanche of criticism was given, in such a way that Joyce compared it to the act of “denouncing opponents during the Cultural Revolution (in China)” (interview, 23 December 2019). A second lesson observation was scheduled for her, and the next day she submitted her resignation for this job that she only did for several months. When recalling the disastrous experience, she still felt a shiver down her spine, and said that this was “the dark period” of her life; she felt “mentally traumatized” and “panic attacks back then due to stress and anxiety” and was “trapped into the unknown” (interview, 6 April 2019).

4.4. Stay or Leave

The “darkness” affected her self-concept and her decision of “staying in or leaving the teaching profession” (interview, 23 December 2019). She doubted her teaching capability and feared for repeating the traumatic episode. She was not sure if she would stay on the teaching frontline. She then chose to work in an NGO until the short-term contract ended in November 2019. Weighing the potential risks and benefits of staying in or leaving the teaching profession, Joyce weathered the disorientation, anxieties, and worries of her transition from a teacher to an education organization officer. Her experiences could be described as a process of “compliance, resistance, and conformity” [

41] (p. 614).

When asked whether she had any plans of resuming teaching, she mentioned a short full-time employment period of a substitute teacher, prior to her administrative work in the NGO. Working as a substitute teacher, Joyce found that the relationships among the colleagues and students are “healthy”, and the working environment and learners were “pleasant” (interview, 6 April 2019). She worked quite satisfactorily there until the contract finished after three months. Then, she proceeded to a non-civil service engagement as an administrative officer in the NGO, as mentioned above.

In an interview shortly after she left the NGO, Joyce compared administrative work and teaching, viewing teaching as more creative, because teachers can present ideas in diverse ways, although they may use the same textbooks. In contrast, the administrative job is just about “following rules and finishing the task”. However, although Joyce identified the advantages of working as a teacher, she was still “determined not to be a teacher on a long-term basis”. She did not find a full-time teacher job that was suitable for her, as she put one of the reasons that “the job doesn’t match with my life stage at the moment”. She prioritized time for family and herself. She recalled the following:

In the past, I thought being a housewife was shameful. I have a master degree which is perceived as knowledgeable or well-educated. But now, it’s worthy for me to sacrifice my career if my time spared can provide my daughter’s spiritual satisfaction by accompanying her….

(interview, 23 December 2019)

The guilt that Joyce felt towards the lack of accompaniment for her daughter obscured her teaching career vision. It seems that she was enjoying her family life a lot, especially when she kept her daughter in good company, always informally homeschooling her, for which she put “I don’t mind sacrificing my career” for her (interview, 23 December 2019).

In addition, the social movement in Hong Kong in 2019 also influenced her attitudes of staying in, or leaving, the teaching profession, as shown by the following:

I really feel that everything is so crazy right now …I am quite worried about my former students. … It was a critical moment for Hong Kong. I found powerless when facing the social movement. …HK has yet more to suffer.

(WhatsApp communication, 24 December 2019)

The above quote showed Joyce’s dilemma, because both her genuine care for students and the negative feelings that were generated from the reality remained.

However, Joyce lingered on the teaching profession. She wanted to see the “smile in students” (interview, 23 December 2019). Also, Joyce started showing enhanced resilience for potential adversity in her future position, as she put, “if things are not too perfect, just treat it as a job” (interview, 7 July 2020). When asked whether she would consider teaching again in September 2020, she gave a positive response, as she thought it was difficult for her to jump into a new industry, and the administrative job she had was not her thing. Interestingly, even her daughter encouraged her to work again. She seemed to have overcome the trauma that she experienced during the above-mentioned “dark period”.

However, Joyce did not secure any teaching job by September 2020. Meanwhile, the pandemic had not got any better and the repercussions of the unstable sociopolitical environment led Joyce to suddenly reconsider whether she should seek a teaching position. She explained the following:

The society is full of negativity… Recently, in the education field, there are incidents regarding teachers’ so-called professional conduct… Teachers’ pay here is above the average for teachers somewhere else, but I am thinking if I am still suitable to be in this field… I don’t hold any expectations toward the education field.

(interview, 16 November 2020)

This thought stretched even further, to the point that she would consider moving the whole family to outside of Hong Kong, mainly for the sake of her daughter.

We are not too old but not too young. If we don’t leave now, it’s harder in future. As we age, the difficulty moving away is higher… If I don’t leave now, I will be sorry for my daughter.

(interview, 16 November 2020)

These quotes revealed how Joyce’s negative teacher identity impacted her beliefs in the education field. The main factors stemmed from the current COVID-19 situation and the drastically changing sociopolitical environment in Hong Kong. Although she believed that being a teacher is a better option, Joyce transformed her identity, from insider experience in the actual setting to peripheral discourse in responding to the changing context [

23].

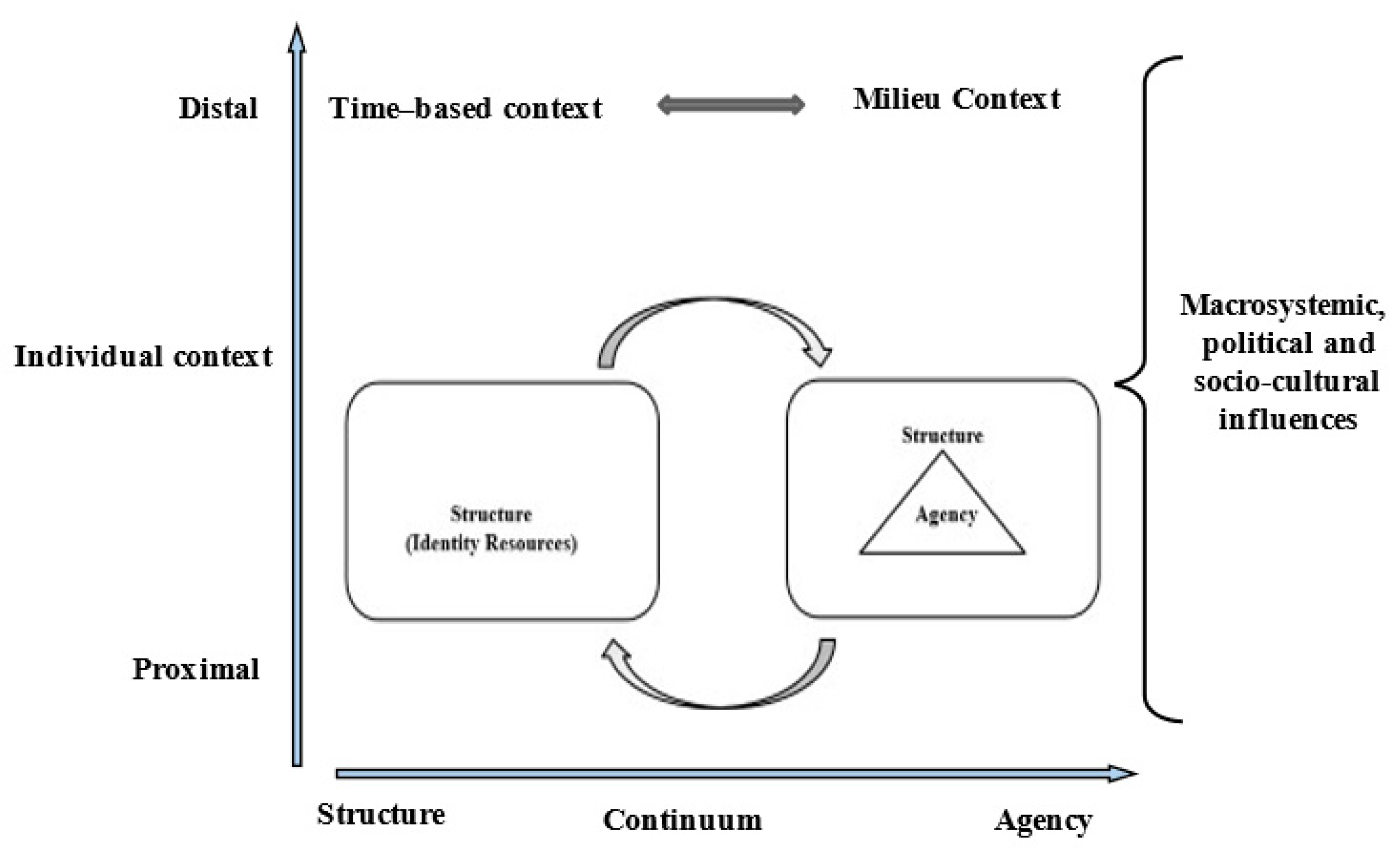

5. Discussion

This study delineates how an ESL teacher (Joyce) exercised her teacher agency to construct her professional identity, during the early years of her teaching career, and how her decisions to stay in or leave the teaching profession were influenced by the complex and intertwined personal and social-institutional factors. Her story revealed that she experienced emotional flux in becoming and being a teacher. In what follows, I would like to outline what might be potentially fruitful directions for future conversations about, and explorations of, professional development, particularly among ESL early career teachers. Related to this purpose, I suggest directions to understand the tensions and dilemmas that are illuminated by this case study. Finally, I reformulate the framework proposed earlier, based on the research findings (

Figure 2).

This framework encapsulates a fluid intersectionality between agency and identity. A number of factors influence the development of professional identity and agency of early career teachers. Time-based and milieu factors are aligned along two dimensions—a distal/proximal axis, and a continuum relating to structure and agency. The fluctuations in the time-based context/milieu context reflect the dynamic macrosystemic, political and socio-cultural influences on the individual decision for agency and identity. A range of internal factors, such as belief and emotion, and external factors, such as sociocultural influences, can impact teacher identity formation and agency development, and leave the development in continual flux. Based on the findings, I explain the features of the framework.

The first feature of this framework is the co-influence between contextual and time-based individual factors. Joyce had worked in three different schools, experiencing different institutional cultures upon graduation from a teacher education program. Joyce resigned from her full-time teaching position at her first school, after working there for only one year, for various reasons, including the geographical distance from her home to the school and a perceived lack of collaboration among her colleagues. She later left her second school when the two-year non-renewable contract ended, and resigned from her third school after working there only two–three months, due to an “insulting” class revisit event.

Joyce’s participation in the teaching community highlights a focus on the interplay between personal, relational, and contextual influences [

23]. In particular, the personal qualities of Joyce, and the socio-institutional settings of her workplaces, were factors that influenced her decisions to make a commitment to, or to leave, the teaching profession. In Joyce’s case, her memories of past experiences, her strong teaching philosophies favoring innovation, and her pedagogical stance, influenced her professional identity, helping her form an image of the ideal teacher. The contexts could include the shattered realities that constrained her teacher agency, such as inadequate collaboration among colleagues, and a sense of disconnection to the teaching community, authoritarian school leadership, the tension between work and family life, sociocultural influences, and the rapidly changing sociopolitical environment. These contextual and societal influences are dynamic, and they determine Joyce’s decision to stay in, or leave, the field over time.

The second feature of this framework is the two axes—distal/proximal and structure/agency. The description of Joyce’s professional trajectory constituted a coherent and flexible frame, through which she interpreted her “becoming, being, and unbecoming” [

14] (p. 869) an ESL teacher in the Hong Kong context. Such process is moving from the distance to the center. As her experiences unfolded, she sought new meanings that would represent her desired identities and her evolving understandings at her first and second school. The identity meanings that she perceived, facilitated her willingness to enact agency in teaching. Her determination to seek meaning from her engagement in school teaching encouraged her to focus her energies on creating her vision as an “innovative” teacher.

However, the structure, which is the recurrent patterned arrangements that influence or limit the choices and opportunities that are available to Joyce, can also influence her capacity to act independently and to make her own free choices. While Joyce sought to act as a teacher in her own right during the initial teaching years, she was later thwarted by the shattered realities in her third school. During a lesson observation, a history teacher, who was not regarded by her as a qualified assessor, made very discouraging and critical comments on her teaching. Such critical incidents that she experienced repeatedly in her third school made her become increasingly frustrated and disheartened. In this particular class observation event, Joyce perceived that her agency in innovating teaching was suppressed by a “lay person” in English teaching. The conflicted positioning heightened her perceptions of alienation. Joyce’s journey illustrates that professional development for early career teachers is related to “whether teachers have the ability to renegotiate their identities” [

42] (p. 34). The structures forced Joyce to move from proximity to distance.

The third feature of this framework is the dynamic intersectionality of factors that mediate the development of identity and agency in early career teachers. For example, mismatches, tensions, and conflicts between her teaching philosophy and the complex reality, impacted Joyce’s sustaining efforts in teaching [

43]. The lack of access to professional development opportunities also confined Joyce to the periphery of the profession, and kept her in a state of survival rather than providing opportunities for her to thrive.

In practice, Joyce did not form identities that oriented what she could do to achieve her goals in teaching, because of a lack of agency, influencing her “exploration of new possibilities for action and new assumptions about context, self and practice” [

24] (p. 28). The mismatch between the perceived and actual practices in teaching also constrained Joyce’s teacher agency. In dealing with the double requirements as a teacher and mother, Joyce found it challenging to “negotiate multiple demands within schools” [

7] (p. 59). The Hong Kong social movement in 2019 also challenged her understandings as a professional teacher. Her efforts to become a teacher were strengthened after a long rest at home because of the pandemic COVID-19, throughout 2020 and beyond. Her identity negotiation as a “leaver” or “stayer” might thus rise and fall in response to contextual or internal triggers.

6. Conclusions

Through an investigation of the teaching lives of an ESL teacher in Hong Kong, this research consolidates the understanding of teacher identity formation as being complex, dynamic, discontinuous, and multi-faceted [

31], and teacher agency as being influenced by the accumulated teacher experiences, previous patterns of thoughts and actions, evolving situation, and future vision [

2]. Evidence from Joyce’s stories points to some key observations, which provide insights into the knowledge base on professional development for early career teachers. Joyce possessed personal qualities, beliefs, and knowledge that facilitated her to manage the challenges in teaching. However, the misalignment with external factors forced her to construct concepts of herself as a teacher that were malleable. The meaning achieved for teacher identity influenced her ability to negotiate the challenges for teacher agency during the early career phase.

Implications can be drawn for school management, government policy makers, and teacher educators in higher education. First, the complex intersectionality in the framework may inform early career teachers’ agency in the teaching contexts with which they engage. This framework has the potential to facilitate beginning teachers to frame their personal narratives about the development of their professional identity in a critically reflective way, which may lead to a powerful sense of agency. Second, the early career ESL teacher’s identity development trajectories reflect the complexities of the professional contexts in which the early career teachers are situated [

44]. The discontinuous, tenuous, and distressed identities convey message about the dynamic and complex individual capacity in seeking agency in the teaching community. Early career teachers need much more personal and professional support than the school can usually provide. In most school situations, interpersonal relationships can work as a buffer, to alleviate the tension between the institution and individual teachers [

44]. Therefore, an open culture and effective communication among colleagues are of primary importance for maintaining the sustainability of professional development for early career teachers [

45,

46]. Finally, the findings suggest greater emphasis on the experiences and circumstances of teacher identity formation. Early career teachers should be given opportunities to reflect on their teaching practice. Guiding teachers to instigate deeper reflection on being and becoming a teacher, and attending to aspects that may not be readily apparent to them during the early career phase, may be a worthwhile pursuit [

47]. Teachers need guidance to reflect on their vulnerability, themselves as teachers, and the possible constraints on teaching practice.