Mapping Participatory Methods in the Urban Development Process: A Systematic Review and Case-Based Evidence Analysis

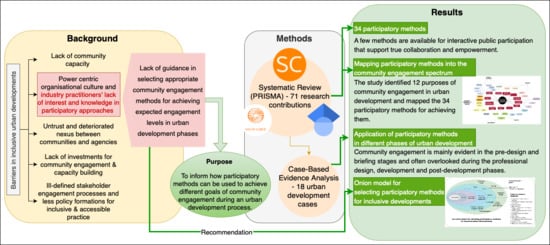

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Q1.

- What are the existing participatory methods that are available for community engagement?

- Q2.

- What level of engagement can be achieved from these existing methods?

- Q3.

- How are these community engagement methods being used in practice? Have these methods been able to achieve the intended purpose?

- Q4.

- Are the current methods sufficient to support community engagement in the entire urban design cycle?

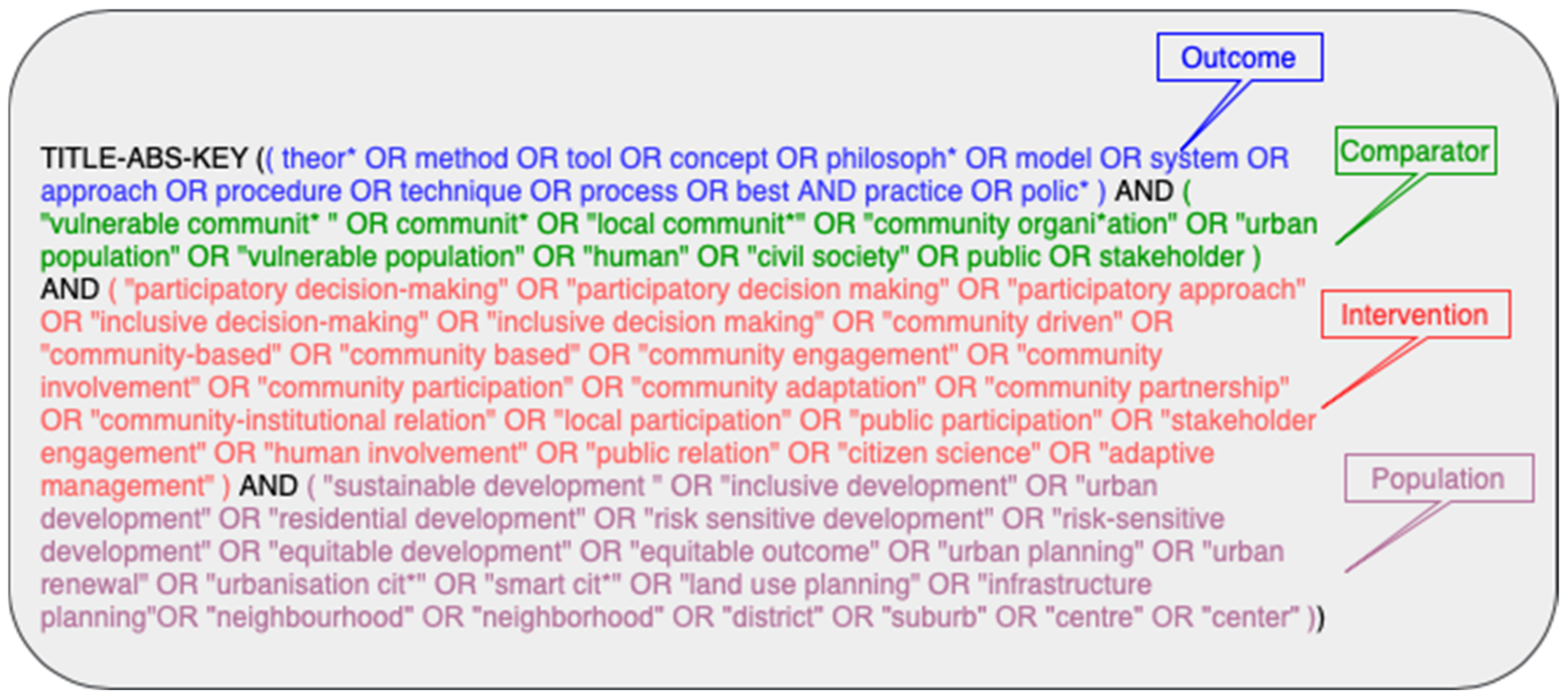

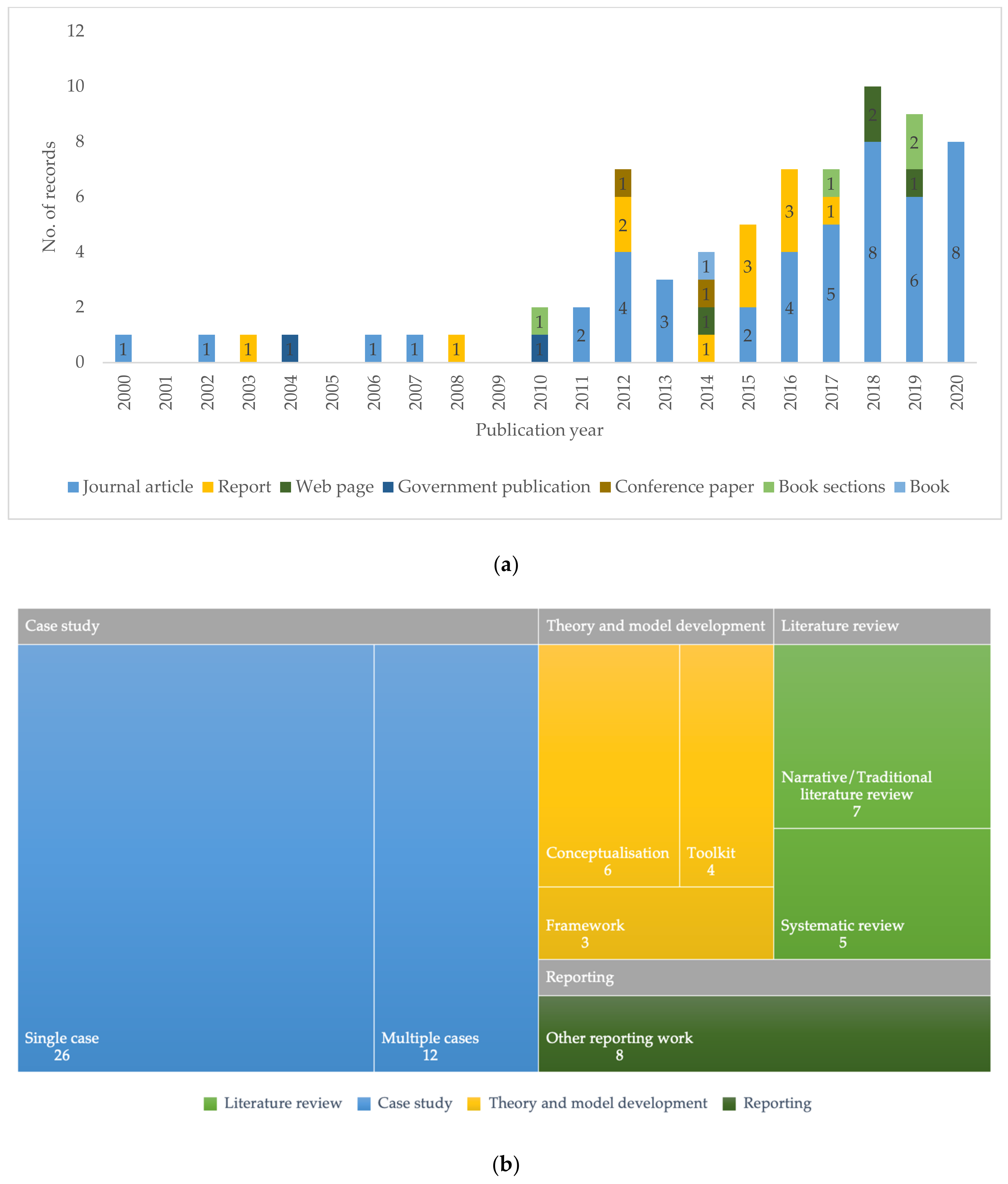

2. Materials and Methods

3. Nexus of Community Engagement with the Urban Development Process

4. Application of Participatory Methods to Achieve Varying Purposes of Public Engagement

4.1. Systematic Review of Community Engagement Methods

4.2. Mapping of Participatory Methods into the Spectrum of Community Engagement

5. Application of Participatory Methods for Inclusive Urban Developments: A Case-Based Evidence Analysis

6. Discussion

6.1. Suggested Model for the Selection of Participatory Methods

6.2. Impact of Covid-19 on Community Engagement

6.3. Study Limitations

7. Conclusions and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision, Online Edition. Available online: https://population.un.org/wup/Publications/Files/WUP2018-Highlights.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2021).

- Savic, B. Community Engagement in Urban Planning and Development; The Prince’s Regeneration Trust: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency—Swiss Federal Office for the Environment. Urban Sprawl in Europe; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Avis, W.R. Urban Governance (Topic Guide); GSDRC, University of Birmingham: Birmingham, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Argüeso, D.; Evans, J.P.; Fita, L.; Bormann, K.J. Temperature response to future urbanization and climate change. Clim. Dyn. 2013, 42, 2183–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, N.; Bauer, A.; Haase, D. Assessing climate impacts of planning policies—An estimation for the urban region of Leipzig (Germany). Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2011, 31, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelekan, I.; Johnson, C.; Manda, M.; Matyas, D.; Mberu, B.; Parnell, S.; Pelling, M.; Satterthwaite, D.; Vivekananda, J. Disaster risk and its reduction: An agenda for urban Africa. Int. Dev. Plan. Rev. 2015, 37, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhatta, B. Causes and consequences of urban growth and sprawl. In Analysis of Urban Growth and Sprawl from Remote Sensing Data; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatta, B.P.; Pandey, R.K. Bhaktapur urban flood related disaster risk and strategy after 2018. J. APF Command Staff Coll. 2020, 3, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Srujan, A.; Shaw, R. Climate disaster resilience: Focus on coastal urban cities in Asia. Asian J. Environ. Disaster Manag. 2011, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badri, S.A.; Asgary, A.; Eftekhari, A.; Levy, J. Post-disaster resettlement, development and change: A case study of the 1990 Manjil earthquake in Iran. Disasters 2006, 30, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godamunne, N. Development and displacement: The national involuntary resettlement policy (NIRP) in practice. Sri Lanka J. Soc. Sci. 2012, 35, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambati, H. Weathering the storm: Disaster risk and vulnerability assessment of informal settlements in Mwanza city, Tanzania. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2013, 70, 919–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muggah, R. Through the developmentalist’s looking glass: Conflict-induced displacement and involuntary resettlement in Colombia. J. Refug. Stud. 2000, 13, 133–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng-Odoom, F. Land reforms in Africa: Theory, practice, and outcome. Habitat Int. 2012, 36, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, W.C. Risks and Rights: The Causes, Consequences, and Challenges of Development-Induced Displacement; The Brookings Institution-SAIS Project on Internal Displacement: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y.; Temeljotov-Salaj, A.; Engebo, A.; Lohne, J. Multi-sector partnerships in the urban development context: A scoping review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 122291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geekiyanage, D.; Fernando, T.; Keraminiyage, K. Assessing the state of the art in community engagement for participatory decision-making in disaster risk-sensitive urban development. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 51, 101847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shand, W. Efficacy in action: Mobilising community participation for inclusive urban development. Urban Forum 2018, 29, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UN-Habitat. Promoting Inclusive, Safe, Resilient and Sustainable Afghan Cities for All. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/partnership/?p=30477 (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Apronti, P.; Osamu, S.; Otsuki, K.; Kranjac-Berisavljevic, G. Education for Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR): Linking theory with practice in Ghana’s basic schools. Sustainability 2015, 7, 9160–9186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations. United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III) Regional Report for Africa: Transformational Housing and Sustainable Urban Development in Africa; United Nations: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Moher, D. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.S. Philosophy and method: Making interpretive research interpretive. In The Routledge Companion to Management Information Systems; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 30–46. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenau, M.; Böhler-Baedeker, S. Citizen and Stakeholder Involvement: A Precondition for Sustainable Urban Mobility. Transp. Res. Procedia 2014, 4, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Glass, J.J. Citizen participation in planning: The relationship between objectives and techniques. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1979, 45, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Community Places. Community Planning Toolkit; Community Places: Belfast, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- International Association for Public Participation. IAP2 Spectrum of Public Participation. Available online: https://iap2.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/2018_IAP2_Spectrum.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Queensland Government. Community Engagement Techniques; Queensland Government: Queensland, Austrailia, 2010.

- Tamarack Institute. Index of Community Engagement Techniques; Tamarack Institute: Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Aslin, H.; Brown, V. Towards Whole of Community Engagement: A Practical Toolkit; Murray-Darling Basin Commission: Canberra, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Customer Service—Communication and Consultation Services. In Community Engagement Framework 2013–2018; The City of Newcastle: Newcastle, Australia, 2012.

- Münster, S.; Georgi, C.; Heijne, K.; Klamert, K.; Noennig, J.R.; Pump, M.; Stelzle, B.; van der Meer, H. How to involve inhabitants in urban design planning by using digital tools? An overview on a state of the art, key challenges and promising approaches. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 112, 2391–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Chin, S.Y.W. Assessing the effectiveness of public participation in neighbourhood planning. Plan. Pract. Res. 2013, 28, 563–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Stakeholder Involvement in Decision Making: A Short Guide to Issues, Approaches and Resources; OECD: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Basco-Carrera, L.; Warren, A.; van Beek, E.; Jonoski, A.; Giardino, A. Collaborative modelling or participatory modelling? A framework for water resources management. Environ. Model. Softw. 2017, 91, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernantes, J.; Maraña, P.; Gimenez, R.; Sarriegi, J.M.; Labaka, L. Towards resilient cities: A maturity model for operationalizing resilience. Cities 2019, 84, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollason, E.; Bracken, L.J.; Hardy, R.J.; Large, A.R.G. Evaluating the success of public participation in integrated catchment management. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 228, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chini, C.M.; Canning, J.F.; Schreiber, K.L.; Peschel, J.M.; Stillwell, A.S. The green experiment: Cities, green stormwater infrastructure, and sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 9, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rodríguez, L.O.; Cisneros, E.; Pequeño, T.; Fuentes, M.T.; Zinngrebe, Y. Building adaptive capacity in changing social-ecological systems: Integrating knowledge in communal land-use planning in the Peruvian Amazon. Sustainability 2018, 10, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perrone, A.; Inam, A.; Albano, R.; Adamowski, J.; Sole, A. A participatory system dynamics modeling approach to facilitate collaborative flood risk management: A case study in the Bradano River (Italy). J. Hydrol. 2020, 580, 124354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, J.; Bukachi, V.; Gregoriou, R.; Venn, N.; Ker-Reid, D.; Travers, A.; Benard, J.; Olang, L.O. Participatory flood modelling for negotiation and planning in urban informal settlements. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Eng. Sustain. 2019, 172, 354–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharifi, A. A critical review of selected tools for assessing community resilience. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 69, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parsons, M.; Glavac, S.; Hastings, P.; Marshall, G.; McGregor, J.; McNeill, J.; Morley, P.; Reeve, I.; Stayner, R. Top-down assessment of disaster resilience: A conceptual framework using coping and adaptive capacities. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2016, 19, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bowen, F.; Newenham-Kahindi, A.; Herremans, I. Engaging the Community: A Systematic Review; University of Calgary: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hardoy, J.; Gencer, E.; Winograd, M. Participatory planning for climate resilient and inclusive urban development in Dosquebradas, Santa Ana and Santa Tomé. Environ. Urban. 2019, 31, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosenstock, T.S.; Lamanna, C.; Chesterman, S.; Hammond, J.; Kadiyala, S.; Luedeling, E.; Shepherd, K.; DeRenzi, B.; van Wijk, M.T. When less is more: Innovations for tracking progress toward global targets. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26–27, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, A.; Pluchinotta, I.; Pengal, P.; Cokan, B.; Giordano, R. Engaging stakeholders in the assessment of NBS effectiveness in flood risk reduction: A participatory system dynamics model for benefits and co-benefits evaluation. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 690, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedelin, B.; Evers, M.; Alkan-Olsson, J.; Jonsson, A. Participatory modelling for sustainable development: Key issues derived from five cases of natural resource and disaster risk management. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 76, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, F.; De Bernardi, P.; Cantino, V. System dynamics modeling as a circular process: The smart commons approach to impact management. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 151, 119799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, S.; van de Ven, F.H.M.; Blind, M.W.; Slinger, J.H. Planning support tools and their effects in participatory urban adaptation workshops. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 207, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadallah, D.M. Utilizing participatory mapping and PPGIS to examine the activities of local communities. Alex. Eng. J. 2020, 59, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, T.; Wójcicki, M. Participation in Public Consultations on Spatial Planning Documents. The Case of Poznań City. Quaest. Geogr. 2016, 35, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raymond, C.M.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Kabisch, N.; Berry, P.; Breil, M.; Nita, M.R.; Geneletti, D.; Calfapietra, C. A framework for assessing and implementing the co-benefits of nature-based solutions in urban areas. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 77, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, E.G.; Giordano, R.; Pagano, A.; van der Keur, P.; Costa, M.M. Using a system thinking approach to assess the contribution of nature based solutions to sustainable development goals. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 738, 139693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Könst, A.; Van Melik, R.; Verheul, W.J. Civic-led public space: Favourable conditions for the management of community gardens. Town Plann. Rev. 2018, 89, 575–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Chapter 3. Citizen participation in land-use planning and urban regeneration in Korea. In The Governance of Land Use in Korea: Urban Regeneration; OECD: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pickering, T.; Minnery, J. Scale and public participation: Issues in metropolitan regional planning. Plan. Pract. Res. 2012, 27, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stańczuk-Gałwiaczek, M.; Sobolewska-Mikulska, K.; Ritzema, H.; van Loon-Steensma, J.M. Integration of water management and land consolidation in rural areas to adapt to climate change: Experiences from Poland and the Netherlands. Land Use Policy 2018, 77, 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejic Bach, M.; Tustanovski, E.; Ip, A.W.; Yung, K.-L.; Roblek, V. System dynamics models for the simulation of sustainable urban development: A review and analysis and the stakeholder perspective. Kybern. Int. J. Syst. Cybern. 2019, 49, 460–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Király, G.; Miskolczi, P. Dynamics of participation: System dynamics and participation—An empirical review. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2019, 36, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andersen, D.F.; Vennix, J.A.; Richardson, G.P.; Rouwette, E.A. Group model building: Problem structuring, policy simulation and decision support. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2007, 58, 691–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stave, K.A. Using system dynamics to improve public participation in environmental decisions. Syst. Dyn. Rev. J. Syst. Dyn. Soc. 2002, 18, 139–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovmand, P.S. Community Based System Dynamics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 1–104. [Google Scholar]

- Bouw, M.; Thoma, D. Economic Resilience Through Community-Driven (Real Estate) Development in Amsterdam-Noord; Springer: Englewood, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Poplin, A. Playful public participation in urban planning: A case study for online serious games. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2012, 36, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, S.N.M.; Rafieian, M. From the kingdom lash to participation: The tale of urban planning in Iran. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2020, 2, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesse, W. Why the Public Voice Matters in Urban Mobility Planning: Lessons from Brazil. Available online: https://thecityfix.com/blog/public-participation-sustainable-urban-mobility-plan-brazil-cities-pac-jesse-worker/ (accessed on 14 March 2021).

- Abd Elrahman, A.S. Tactical ubanism “A pop-up local change for Cairo’s built environment”. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 216, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prince’s Foundation for Building Community. Newmarket Enquiry by Design Workshop Report; Prince’s Foundation for Building Community: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Auckland Design Manual. Tōia Multi-Purpose Community Facility; Auckland Design Manual: Auckland, New Zealand, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kirshen, P.; Ballestero, T.; Douglas, E.; Miller Hesed, C.D.; Ruth, M.; Paolisso, M.; Watson, C.; Giffee, P.; Vermeer, K.; Bosma, K. Engaging vulnerable populations in multi-level stakeholder collaborative urban adaptation planning for extreme events and climate risks—A case study of East Boston USA. J. Extrem. Events 2018, 5, 1850013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, P. The limits to participation: Urban poverty and community driven development in Rajshahi City, Bangladesh. Community Dev. 2018, 49, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakidis, C. Citizen and city: Issues related in public participation in the process of spatial planning. In Proceedings of the 3rd National Conference of Planning and Regional Development, University of Thessaly, Volos, Greece, 27–30 September 2012; pp. 27–30. [Google Scholar]

| Categories | Filters |

|---|---|

| Search fields | Title, Abstract, Keywords |

| Publication year | From 2000 to 2020 |

| Subject/ Research area | Social science, Social work, Sociology, Social issues, Psychology, Arts and Humanities, Urban Studies, Development Studies, Decision making |

| Document type | Article, Proceeding’s paper, Book, Book section |

| Language | English |

| Participatory Method | Examples of Tools | Strengths | Limitations | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presentation and dissemination of information | ||||

| Printed material |

|

| • A traditional method, hence, does not reach the younger generation | [30,31,32,33,34,35] |

| Advertising, Media coverage |

| • Can be readily accessible by a wider community |

| [31,33,34,36,37] |

| Displays/Exhibits | • Set up at relevant public locations (e.g., libraries, ward or electorate offices, shopping centres, community festivals, etc.) |

|

| [30,31,32,33] |

| Presentations, Live streaming, Videos |

|

|

| [31,32,33] |

| Website |

|

|

| [30,31,32,33,34,36,38,39,40] |

| Infographics |

|

|

| [31,36] |

| Dissemination of information and building conversations | ||||

| Social media |

|

| • Need access to digital devices | [31,33,34,36,37] |

| Field observations | ||||

| Site visits/Tours |

| • A theoretical or abstract discussion can be brought into focus by seeing direct evidence that is available in the field or at a specific location | • Expensive planning | [31,41] |

| Public awareness | ||||

| Public meetings |

|

|

| [30,42] |

| Opinion collection from a selected group of general public | ||||

| Interviews |

| • Generate in-depth information on a specific topic |

| [17,30,31,32,33,39,42,43,44,45,46,47] |

| Focus groups |

| • Can explore different perspectives of a small group of people of a common issue/goal | • Not effective for providing information to the public | [30,31,32,33,41,47] |

| Opinion collection from a large body of the general public | ||||

| Polls |

|

|

| [30,31,32,33,36] |

| Surveys |

|

|

| [17,30,31,32,33,35,39,42,43,44,45,46] |

| Citizen science, Crowdsourcing ideas |

|

| • Assessing the quality of the provided data and identifying bias is difficult | [31,36,48] |

| Gathering expertise and scientific knowledge | ||||

| Expert panels, Working groups |

|

| • Expensive in recruiting experts | [31,32,41] |

| Mapping ideas | ||||

| System dynamics (SD) |

|

| • Complex and need advanced knowledge in the application | [37,38,42,49,50,51,52] |

| Community mapping/Mind mapping |

|

|

| [31,53,54] |

| Bring deliberation and public participation into public policy decisions | ||||

| Citizen juries |

|

|

| [31,32,33,41] |

| Citizen committees |

|

|

| [31,35] |

| Visioning |

| • Brings citizens and stakeholders together to assist a group of stakeholders in developing a shared vision of the future |

| [26,30,31,32] |

| Community indicator projects | • Community Indicators’ Consortium toolbox |

| • Require long-term commitment | [31] |

| Creating solutions | ||||

| Workshop, Open space events |

|

|

| [30,31,32,34,35,41,47,55] |

| Design charrette, Tactic-urbanism (Placemaking, Pop-ups) |

| • Provide a forum for ideas and offers the unique advantage of giving immediate feedback to the designers |

| [31] |

| Knowledge/ document co-creation | • Open Innovation Digital Platforms | • Allow for the collection of indigenous wisdom and creating design solutions with social empathy and inclusion | • High dependence on communities’ views/interests | [38,50,55,56,57] |

| Participatory asset management | ||||

| Asset-based community development (ABCD) |

|

|

| [31,32] |

| Participatory budgeting (PB) |

|

|

| [2,31,58,59,60] |

| Participatory monitoring and evaluation | ||||

| Most significant change (MSC) |

|

|

| [31] |

| UD Project (Country, Year) | Project Purpose | Community Engagement Objective(s) | Targeted UD Phase(s) | Degree of Community Engagement | Participatory Method(s)/Tool(s) Used | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Design Analysis | Briefing | Professional Design | Development | Post- Development | Inform | Consult | Involve | Collaborate | Empower | ||||

| A. Metro Vancouver 2040 (Canada, 2010) [59] | To develop the regional growth strategy | • Foster public understanding of the purpose of regional planning | X | X |

| ||||||||

| • Discuss the key regional policies and seek public comment | X | X |

| ||||||||||

| B. Victoria Square development (New Zealand, 2015) [2] | To provide opportunities for the public to contribute views and ideas for the future refurbishment of Victoria Square |

| X | X |

| ||||||||

| C. Future Visioning of Urban Landscapes (USA) [3] | To explore new uses of urban landscapes | • Sequential refinement and crystalli-sation of key issues and ideas within large groups of people. | X | X | • World Café: community tables | ||||||||

| D. NextCampus (Germany, 2012) [67] | Moving campus facility into a new location |

| X | X | • Serious games (online) including playful elements such as storytelling, virtual walking, sketching, drawing, and gaming | ||||||||

| E. The Bandar-Abbas City Informal Settlements Upgrading project (BACISU) (Iran, 2012) [68] | To create safe residential zones, habitation, ownership rights and provide access to financial sources for low-income groups (funded by the World Bank) | • To seek public opinion in the preparation of the city vision | X | X |

| ||||||||

| F. Metropolitan Florianópolis’s ambitious new sustainable mobility plan (PLAMUS) (Brazil, 2014) [69] | Developing a metropolitan mobility plan | • To include community ideas into the metropolitan mobility plan | X | X | • Public surveys | ||||||||

| X | X |

| |||||||||||

| G. Building urban flood resilience (Kenya, 2015) [43] | To develop a flood model integrating community perspectives | • To produce flood depth and extent maps on a range of scales to support stakeholder consultations; overlay of community data and major and minor infrastructure planning | X | X | • Participatory flood modelling (mapping) | ||||||||

| H. UR[BNE] (Australia, 2012) [2] | To create greater public involvement and understanding of how urban places are designed, building pride and interest in Brisbane’s places, and generally livening up the city. | • Change people’s perception of urban spaces from that of ‘an uninspiring, one-dimensional offer’ to ‘vibrant, activated destinations’. | X | X | • Open space events-annual community festival including music, live art, street picnics, fashion parades, urban design film screenings, bike rides, walking tours and photo hunts | ||||||||

| I. Maroochydore centre master planning process (Australia, 2014) [2] | To masterplan the Maroochydore centre | • Produce different masterplan options | X | X | • City shape models (worked in small groups) | ||||||||

| J. The 7th Havana Urban Design Charrette (Cuba, 2014) [2] | To develop urban strategies and proposals for the El Vedado neighbourhood of Havana |

| X | X | • Design Charrette | ||||||||

| K. Luxor Street in Mansheit Nasser (Egypt, 2015) [70] | Improving the living conditions and quality of life for people in poor areas, through restraining the socioeconomic problems | • To identify the population’s key need to develop a touristic street | X | X | • Public survey | ||||||||

| • To shaping the urban space | X | X | • Tactic urbanism (Placemaking/Pop-ups) | ||||||||||

| L. Newmarket urbanism project (United Kingdom, 2012) [71] | To create a sustainable and holistic vision for Newmarket | • To establish Newmarket’s key issues, opportunities and challenges | X | X | • Scoping workshop | ||||||||

| • To refine the draft Vision Statements (from the Scoping Workshop), develop practical Action Plans, and address issues of growth and the benefits it could bring for the town | X | X |

| ||||||||||

| M. Tōia (New Zealand, 2015) [72] | Designing a multi-purpose community facility | • To incorporate Mario’s cultural values and its people’s needs. | X | X | X | • Meetings | |||||||

| X | X | • Commissioning with artists who undertook the artworks | |||||||||||

| N. Greenovate Boston 2014 Climate Action Plan (United States, 2014–present) [73] | To develop Boston’s Climate Action Plan |

| X X | X |

| ||||||||

| X | X | X |

| ||||||||||

| X | X |

| |||||||||||

| X | X | • Interactive workshop | |||||||||||

| O. Urban reform process (Afghanistan, 2019–present) [20] | To improve the living conditions of Afghan citizens, who live in informal housing and slums (funded by UN-Habitat) |

| X | X | X | X | X | • Community Development Councils | |||||

| P. Christchurch Pop-Ups (New Zealand, 2011) [2] | To swiftly rebuild the city centre after the 2011 earthquake | • Rebuilt temporary city structures until longer-term solutions are found | X | X | X | X | X | X | • Placemaking | ||||

| Q. City of Harare project (Zimbabwe, 2014) [19] | Mobilising community participation for inclusive urban development | • To provide a structure for micro-savings and loans among members | X | X | X | X | • Savings groups (citizen committees) | ||||||

| • To facilitate the creation of social bonds | X | X | X | X | X | X | • Weekly meetings | ||||||

| R. Urban Partnerships for Poverty Reduction (UPPR) program (Bangladesh, 2014) [74] | Urban slum upgrading project (funded by United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and UN-Habitat and the UK Government (UKaid)) |

| X | X | X | X | X | X | • Community Development Committees (CDCs) | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Geekiyanage, D.; Fernando, T.; Keraminiyage, K. Mapping Participatory Methods in the Urban Development Process: A Systematic Review and Case-Based Evidence Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8992. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168992

Geekiyanage D, Fernando T, Keraminiyage K. Mapping Participatory Methods in the Urban Development Process: A Systematic Review and Case-Based Evidence Analysis. Sustainability. 2021; 13(16):8992. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168992

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeekiyanage, Devindi, Terrence Fernando, and Kaushal Keraminiyage. 2021. "Mapping Participatory Methods in the Urban Development Process: A Systematic Review and Case-Based Evidence Analysis" Sustainability 13, no. 16: 8992. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168992

APA StyleGeekiyanage, D., Fernando, T., & Keraminiyage, K. (2021). Mapping Participatory Methods in the Urban Development Process: A Systematic Review and Case-Based Evidence Analysis. Sustainability, 13(16), 8992. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168992