The Impact of Coronavirus COVID-19 Pandemic on Food Purchasing, Eating Behavior, and Perception of Food Safety in Kuwait

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review: Impact of COVID-19 on Food Purchasing, Eating Behaviors and Food Safety

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design and Participants

3.2. Questionnaire

3.3. Ethical Approval

3.4. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

4.2. Food Purchasing Behaviors

4.2.1. Gender Comparison

4.2.2. Nationality Comparison

4.3. Food Safety

4.3.1. Gender Comparison

4.3.2. Nationality Comparison

4.4. Food Consumption

4.4.1. Gender Comparison

4.4.2. Nationality Comparison

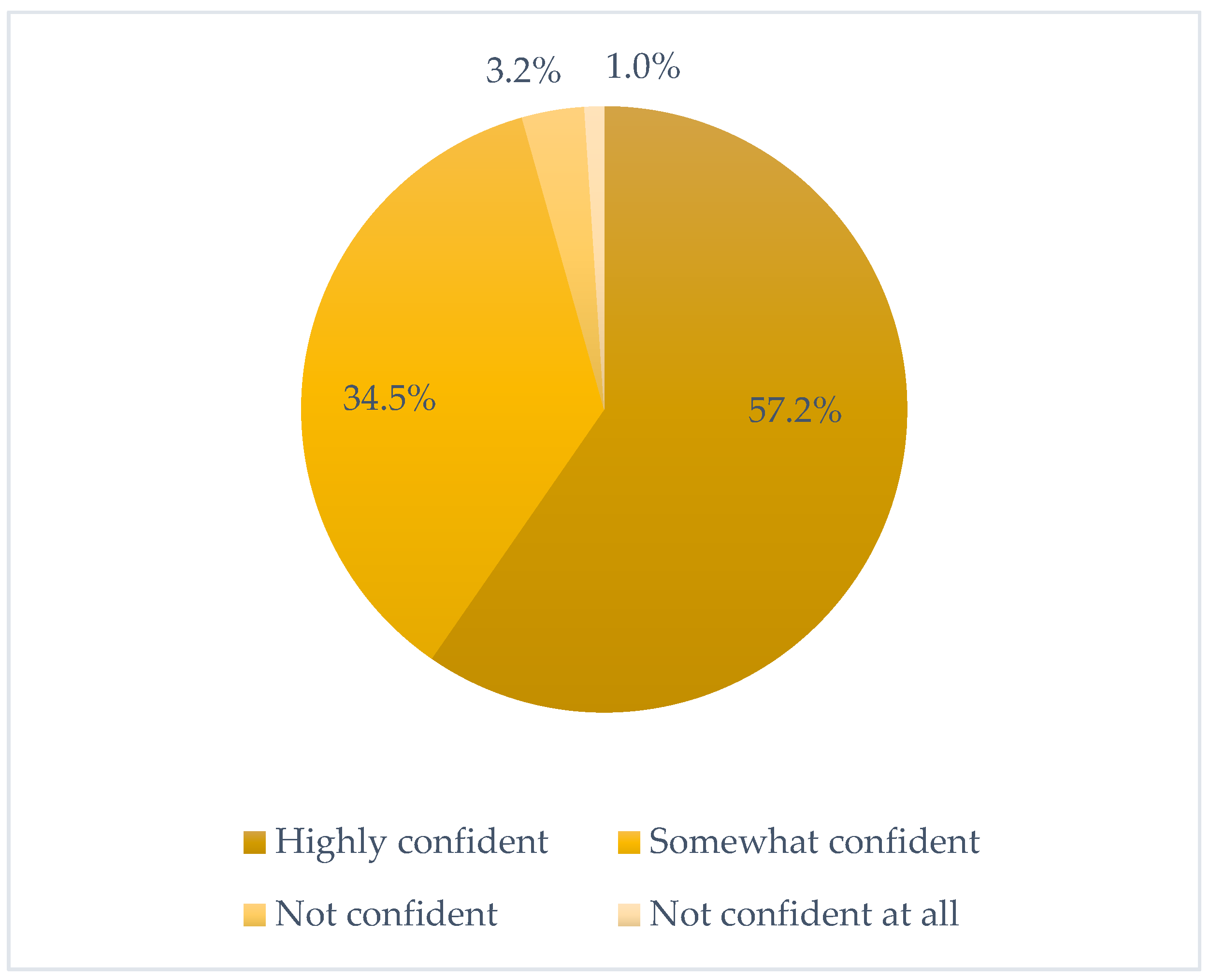

4.5. Perception of Food Security

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andersen, K.G.; Rambaut, A.; Lipkin, W.I.; Holmes, E.C.; Garry, R.F. The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 450–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, G.; Cai, X.-P.; Deng, J.-W.; Zheng, L.; Zhu, H.-H.; Zheng, M.; Yang, B.; Chen, Z. An overview of COVID-19. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2020, 21, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19, 11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-mediabriefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Huang, C.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Ren, L.; Zhao, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, G.; Xu, J.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020, 395, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, N.; Zhou, M.; Dong, X.; Qu, J.; Gong, F.; Han, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Y.; et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet 2020, 15, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Advice for the Public. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- WHO. COVID-19 Question and Answer, Food Safety. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/food-safety-and-nutrition#:~:text=delivery (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- Circular of the Civil Service Bureau No.7 2020, Kuwait. Available online: https://www.kuwaitculture.com/civil-service-commission/civil-service-rules-and-regulations (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- COVID-19 (Coronavirus): Panic Buying and Its Impact on Global Health Supply Chains; World Bank Blogs. 2020. Available online: https://blogs.worldbank.org/health/covid-19-coronavirus-panic-buying-and-its-impact-global-health-supply-chains (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Mao, F. Coronavirus Panic: Why Are People Stockpiling Toilet Paper? 2020. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-51731422 (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Sterman, J.D.; Dogan, G. I’m not hoarding, I’m just stocking up before the hoarders get here: Behavioral causes of phantom ordering in supply chains. J. Operat. Manag. 2015, 39, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Commerce and Industry Kuwait. Available online: www.moci.gov.kw (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- Martin-Neuninger, R.; Ruby, M.B. What does food retail research tell us about the implications of Coronavirus (COVID-19) for grocery purchasing habits? Front. Psychol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, D. COVID-19 lockdowns throughout the world. Occup. Med. 2020, 70, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilder-Smith, A.; Freedman, D. Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: Pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). COVID-19 and its Impact on Food Security in the Near East and North Africa: How to respond? 2020. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/ca8778en/CA8778EN.pdf (accessed on 5 October 2020).

- Erokhin, V.; Gao, T. Impacts of COVID-19 on trade and economic aspects of food security: Evidence from 45 developing countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béné, C. Resilience of local food systems and links to food security–A review of some important concepts in the context of COVID-19 and other shocks. Food Secur. 2020, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. COVID-19 and the Food and Agriculture Sector: Issues and Policy Responses; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- HLPE. Interim Issues Paper on the Impact of COVID-19 on Food Security and Nutrition (FSN) by the High-Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE); FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Policy Brief: The Impact of COVID-19 on Food Security and Nutrition; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Recchia, L.; Cappelli, A.; Cini, E.; Garbati Pegna, F.; Boncinelli, P. Environmental Sustainability of Pasta Production Chains: An Integrated Approach for Comparing Local and Global Chains. Resources 2019, 8, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- FAO. Food Outlook—Biannual Report on Global Food Markets; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Beard-Knowland, T. The Impact of Covid-19 on How We Eat. 2020. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/publication/documents/2020-05/impact_of_covid-19_on_how_we_eat_ipsos_sia.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Baker, S.; Meyer, S.; Pagel, M.; Yannelis, C. How Does Household Spending Respond to an Epidemic? Consumption during the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic; NBER Working Papers 26949; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/nbr/nberwo/26949.html (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Grasso, S. Consequences of Panic Buying, IFNH. Available online: https://research.reading.ac.uk/ifnh/2020/04/20/consequences-of-panic-buying/ (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Cranfield, J.A.L. Framing consumer food demand responses in a viral pandemic. Can. J. Agric. Econ. Can. Agroecon. 2020, 68, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Lee, L.; Yap, A.J. Control Deprivation Motivates Acquisition of Utilitarian Products. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 43, 1031–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition. Food Environments in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://www.unscn.org/en/news-events/recent-news?idnews=2040 (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- IPES-Food. COVID-19 and the Crisis in Food Systems: Symptoms, Causes, and Potential Solutions. 2020. Available online: http://www.ipes-food.org/_img/upload/files/COVID-19_CommuniqueEN%282%29.pdf (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Evers, C.; Dingemans, A.; Junghans, A.F.; Boevé, A. Feeling bad or feeling good, does emotion affect your consumption of food? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 9, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moynihan, A.B.; van Tilburg, W.A.; Igou, E.R.; Wisman, A.; Donnelly, A.E.; Mulcaire, J.B. Eaten up by boredom: Consuming food to escape awareness of the bored self. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, C.; Gökmen, V. Neuroactive compounds in foods: Occurrence, mechanism and potential health effects. Food Res. Int. 2020, 128, 108744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarmozzino, F.; Visioli, F. Covid-19 and the Subsequent Lockdown Modified Dietary Habits of Almost Half the Population in an Italian Sample. Foods 2020, 9, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Renzo, L.; Gualtieri, P.; Pivari, F.; Soldati, L.; Attinà, A.; Cinelli, G.; Leggeri, C.; Caparello, G.; Barrea, L.; Scerbo, F.; et al. Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: An Italian survey. J. Transl. Med. 2020, 18, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammar, A.A.; Brach, M.; Trabelsi, K.; Chtourou, H.; Boukhris, O.; Masmoudi, L.; Bouaziz, B.; Bentlage, E.; How, D.; Ahmed, M.; et al. Effects of COVID-19 Home Confinement on Eating Behaviour and Physical Activity: Results of the ECLB-COVID19 International Online Survey. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jribi, S.; Ben Ismail, H.; Doggui, D.; Debbabi, H. COVID-19 virus outbreak lockdown: What impacts on household food wastage? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 3939–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The Food Industry Association. U.S. Grocery Shopper Trends: The Impact of COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.fmi.org/docs/default-source/webinars/trends-covid-19-webinar.pdf?sfvrsn=307a9677_0 (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Ben Hassen, T.; El Bilali, H.; Allahyari, S.M. Impact of COVID-19 on Food Behavior and Consumption in Qatar. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Q&A: COVID-19 Pandemic-Impact on Food and Agriculture Q1: Will Covid-19 Have Negative Impacts on Global Food Security? FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Consumer Survey: COVID-19’s Impact on Food Purchasing, Eating Behaviors and Perceptions of Food Safety. 14 April 2020. Available online: https://foodinsight.org/consumer-survey-a-second-look-at-covid-19s-impact-on-food-purchasing-eating-behaviors/ (accessed on 25 April 2020).

- Wild, D.; Grove, A.; Martin, M.; Eremenco, S.; McElroy, S.; Verjee-Lorenz, A.; Erikson, P. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: Report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value Health 2005, 8, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Górnicka, M.; Drywień, M.E.; Zielinska, M.A.; Hamułka, J. Dietary and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 and the subsequent lockdowns among Polish adults: A Cross-sectional online survey PLifeCOVID-19 study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschasaux-Tanguy, M.; Druesne-Pecollo, N.; Esseddik, Y.; de Edelenyi, F.S.; Allès, B.; Andreeva, V.A.; Baudry, J.; Charreire, H.; Deschamps, V.; Egnell, M.; et al. Diet and physical activity during the COVID-19 lockdown period (March–May 2020): Results from the French NutriNet-Sante cohort study. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, W.; Ashkanani, F. Does COVID-19 Change Dietary Habits and Lifestyle Behaviours in Kuwait? Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2020, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheikh Ismail, L.; Osaili, T.M.; Mohamad, M.N.; Al Marzouqi, A.; Jarrar, A.H.; Abu Jamous, D.O.; Magriplis, E.; Ali, H.I.; Al Sabbah, H.; Hasan, H.; et al. Eating habits and lifestyle during COVID-19 lockdown in the United Arab Emirates: A cross-sectional study. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschasaux-Tanguy, M.; Druesne-Pecollo, N.; Esseddik, Y.; de Edelenyi, F.S.; Allès, B.; Andreeva, V.A.; Baudry, J.; Charreire, H.; Deschamps, V.; Egnell, M.; et al. Diet and physical activity during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) lockdown (March–May 2020): Results from the French NutriNet-Santé cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 924–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutani, S.; Cooper, J.A. COVID-19 related home confinement in adults: Weight gain risks and opportunities. Obesity 2020, 28, 1576–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, M.; Ponzo, V.; Rosato, R.; Scumaci, E.; Goitre, I.; Benso, A.; Belcastro, S.; Crespi, C.; De Michieli, F.; Ghigo, E.; et al. Changes in weight and nutritional habits in adults with obesity during the “lockdown” period caused by the COVID-19 virus emergency. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- New World. COVID-19 Update. Updates from the New World team About COVID-19 and Our Stores, 2020. Available online: https://www.newworld.co.nz/covid-19 (accessed on 12 August 2020).

- Countdown. COVID-19 (Coronavirus) Latest Update. 2020. Available online: https://www.countdown.co.nz/community-environment/covid-19 (accessed on 15 October 2020).

- Center of Diseases and Control, Food and COVID-19. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/food-and-COVID-19.html (accessed on 4 August 2020).

- Scaraboto, D.; Joubert, A.M.; Gonzalez-Arcos, C. Using lots of plastic packaging during the coronavirus crisis? You’re not alone. Conversation 2020, 668, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar]

| All (n = 841) n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 186 (22.1) |

| Female | 655 (77.9) |

| Age Category | |

| 18–25 years | 52 (6.2) |

| 26–40 years | 303 (36) |

| 41–65 years | 431 (51.2) |

| Older than 65 years | 55 (6.5) |

| Nationality | |

| Non-Kuwaiti | 136 (16.2) |

| Kuwaiti | 705 (83.8) |

| Governorate | |

| Capital | 380 (45.2) |

| Hawalli | 278 (33.1) |

| Farwania | 42 (5.0) |

| Mubarak Al Kabeer | 75 (8.9) |

| AlAhmadi | 46 (5.5) |

| AlJahra | 20 (2.4) |

| Gender n (%) | Nationality n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Non-Kuwaiti | Kuwaiti | |

| Food purchasing habits changed | 137 (73.7) | 486 (74.2) | 112 (82.4) * | 511 (72.5) |

| How did food purchase change? | ||||

| Shop more | 39 (21.0) | 101 (15.4) | 12 (8.8) | 128 (18.2) * |

| Shop less | 70 (37.6) | 300 (45.8) * | 73 (53.7) * | 297 (42.1) |

| Shorter shopping duration | 42 (22.6) | 173 (26.4) | 50 (36.8) * | 165 (23.4) |

| Prefer online shopping | 47 (25.0) | 213 (32.5) | 27 (19.9) | 233 (33.0) * |

| Purchase more food each time I shop | 40 (21.5) | 160 (24.4) ** | 39 (28.7) ** | 161 (22.8) |

| Purchase dry food more | 63 (32.3) | 169 (25.8) | 56 (41.2) | 176 (25.0) |

| Purchase frozen food more | 60 (32.0) | 183 (28.0) | 37 (27.2) | 206 (29.2) |

| Purchase canned food more | 32 (17.2) * | 71 (10.8) | 20 (14.7) | 83 (11.8) |

| Purchase fresh food less | 30 (16.1) | 109 (16.6) | 23 (16.9) | 116 (16.6) |

| Worry while purchasing food | ||||

| Fear of infection | 128 (68.8) | 471 (71.9) | 106 (77.9) | 493 (69.9) |

| Not enough food | 66 (35.5) * | 169 (25.8) | 37 (27.2) | 198 (28.1) |

| Not enough money | 9 (4.8) | 33 (5.0) | 24 (17.6) ** | 18 (2.6) |

| Difficulty reaching supermarket | 85 (45.7) | 295 (45.0) | 56 (41.2) | 324 (46.0) |

| No worries | 24 (12.9) | 73 (11.1) | 10 (7.4) | 87(12.3) |

| Type of food you ensured having at home | ||||

| Dry food (rice, oats and lentils) | 147 (79.0) | 489(74.7) | 111(81.6) | 525 (74.5) |

| Fresh produce (dairy, fruits) | 119 (64.0) | 458(69.9) | 93 (68.4) | 484 (68.7) |

| Candy and savory snacks | 39 (21.0) * | 91(13.9) | 15 (11.0) | 115 (16.3) |

| Ready-made frozen food | 46 (24.7) | 210 (32.1) * | 9 (6.6) | 247 (35.9) ** |

| Canned food (tuna, fava beans, chickpeas) | 89 (48.0) * | 230 (35.1) | 62 (45.6) * | 257 (36.5) |

| Gender n (%) | Nationality n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Non-Kuwaiti | Kuwaiti | |

| Supermarket food safety | ||||

| Yes, I trust the food I purchase | 80 (43.0) | 348(53.1) * | 62 (45.6) | 366 (51.9) |

| Yes, I somewhat trust the food I purchase | 70 (37.6) | 224 (34.2) | 53 (39.0) | 241 (34.2) |

| No, I don’t trust the food I purchase | 20 (10.8) * | 38 (5.8) | 11 (8.1) | 47 (6.7) |

| No, not at all I don’t trust the food I purchase | 6 (3.2) * | 6 (0.9) | 1 (0.7) | 11 (1.6) |

| Restaurant and food delivery safety | ||||

| Yes, I trust the food I purchase | 24 (12.9) * | 45 (6.9) | 12 (8.8) | 57 (8.1) |

| Yes, I somewhat trust the food I purchase | 45 (24.2) | 150 (22.9) | 27 (19.9) | 168 (23.8) |

| No, I don’t trust the food I purchase | 59 (31.7) | 220 (33.6) | 39 (28.7) | 240 (34.0) |

| No, not at all I don’t trust the food I purchase | 44 (23.7) | 191 (29.2) | 46 (33.8) | 189 (26.8) |

| Steps taken during shopping to feel safe | ||||

| Shop online | 75 (40.3) | 285 (43.5) | 30 (22.1) | 330 (46.8) ** |

| Visit the grocery store less often | 111 (59.7) | 429 (65.5) | 92 (67.6) | 448 (63.5) |

| Shop during less busy periods | 115 (61.8) | 393 (60.0) | 88 (64.7) | 420 (59.6) |

| Avoid touching surfaces/products while I shop | 83 (44.6) | 327(49.9) | 80 (58.8) * | 330 (46.8) |

| Use sanitizers and wipes while I shop | 89 (47.8) | 404 (61.7) ** | 78 (57.4) | 415 (58.9) |

| Purchase more frozen and canned food | 34 (18.3) | 92 (14.0) | 23 (16.9) | 103 (14.6) |

| Purchase less fresh food | 18 (9.7) | 52 (7.9) | 11 (8.1) | 59 (8.4) |

| Pay using my card instead of cash | 117 (62.9) | 474 (72.4) * | 85 (62.5) | 506 (71.8) * |

| Leave my purchases for 2 h once I am home | 17 (9.1) | 107 (16.3) * | 17 (12.5) | 107 (15.2) |

| Clean my purchases when I arrive home | 96 (51.6) | 371 (56.6) | 73 (53.7) | 394 (55.9) |

| Wash my hands after shopping | 155 (83.3) | 581 (88.7) | 121 (89.0) | 615 (87.2) |

| Dispose of the shopping bags and packaging | 90 (48.4) | 366 (55.9) | 89 (65.4) * | 367 (52.1) |

| No change | 7 (3.8) | 14 (2.1) | 2 (1.5) | 19 (2.7) |

| Steps that should be taken by staff and food handlers | ||||

| Wash surfaces that regularly touched | 140 (75.3) | 498 (76.0) | 101 (74.3) | 537 (76.2) |

| Providing wipes and sanitizers | 92 (49.5) | 348 (53.1) | 72 (52.9) | 368 (52.2) |

| Wearing gloves and masks during work | 153 (82.3) | 555 (84.7) | 111(81.6) | 597 (84.7) |

| Cleaning food containers regularly | 74 (39.8) | 324 (49.5) * | 62 (45.6) | 336 (47.7) |

| Ensure staff follow social distancing measuring | 116 (62.4) | 458(69.9) | 87 (64.0) | 487 (69.1) |

| Gender n (%) | Nationality n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Non-Kuwaiti | Kuwaiti | |

| Did your food consumption habits change? | ||||

| Food consumption increased | 65 (34.9) | 218 (33.3) | 39 (28.7) | 244 (34.6) |

| Food consumption decreased | 44 (23.7) * | 111(16.9) | 26 (19.1) | 129 (18.3) |

| Food consumption stayed the same | 71 (38.2) | 297(45.3) | 66 (48.5) | 302 (42.8) |

| Reason for increase in food consumption | ||||

| Anxiousness/fear | 22 (11.8) | 59 (9.0) | 13 (9.6) | 68 (9.6) |

| Lockdown (partial/full) | 50 (26.9) | 177(27.0) | 32 (23.5) | 195 (27.7) |

| Watching TV/electronics | 23 (12.4) | 99 (15.1) | 16 (11.8) | 106 (15.0) |

| More food at home | 14 (7.5) | 49 (7.5) | 9 (6.6) | 54(7.7) |

| Reason for decrease in food consumption | ||||

| Anxiousness/fear | 9 (4.8) | 46 (7.0) | 13 (9.6) | 42 (6.0) |

| Lockdown (partial/full) | 19 (10.2) | 64 (9.8) | 12 (8.8) | 71 (10.1) |

| Less money available | 2 (1.1) | 14 (2.1) | 13 (9.6) ** | 3 (0.4) |

| Less food at home | 9 (4.8) * | 8(1.2) | - | 17 (2.4) |

| How did your food consumption change? | ||||

| I eat more food prepared at home | 154 (82.8) | 574(87.6) | 107 (78.7) | 621 (88.1) * |

| I eat less food from restaurants | 125 (67.2) | 445 (67.9) | 106 (77.9) * | 464 (65.8) |

| I eat less food than usual | 21(11.3) | 107 (16.3) | 19 (14.0) | 109 (15.5) |

| I eat more food than usual | 27 (14.5) | 74 (11.3) | 12 (8.8) | 89 (12.6) |

| I eat healthy food more than usual | 59 (31.7) | 272 (41.5) * | 57 (41.9) | 274 (38.9) |

| I eat healthy food less than usual | 10 (5.4) | 31 (4.7) | 8 (5.9) | 33 (4.7) |

| Eating habits did not change | 25 (13.4) | 100(15.3) | 20 (14.7) | 105 (14.9) |

| What type of food did you eat more of? | ||||

| Dairy products (milk and cheese) | 83 (44.6) | 280 (42.7) | 53 (39.0) | 310 (44.0) |

| Baked goods and pastries | 85 (45.7) | 266 (40.6) | 41 (30.1) | 310 (44.0) * |

| Pasta | 59 (31.7) | 173 (26.4) | 31 (22.8) | 201 (28.5) |

| Rice | 90 (48.4) ** | 205 (31.3) | 47 (34.6) | 248 (35.2) |

| Fruits and vegetables | 101 (54.3) | 322 (49.0) | 72 (52.9) | 351 (49.8) |

| Legumes and pulses | 88 (47.3) | 261 (39.8) | 61 (44.9) | 288 (40.9) |

| Meat, poultry and eggs | 59 (31.7) | 150 (22.9) | 32 (23.5) | 177 (25.1) |

| Fish and seafood | 50 (26.9) | 148(22.6) | 36 (26.5) | 162 (23.0) |

| Desserts and savory snacks | 33 (17.7) | 150 (22.9) | 24 (17.6) | 159 (22.6) |

| Fast food | 2 (1.1) | 17 (2.6) | 2 (1.5) | 17 (2.4) |

| No change | 31 (16.7) | 167(25.5) | 37 (27.2) | 161 (22.8) |

| What type of beverages did you have more of? | ||||

| Water | 145 (78.0) | 441(67.3) | 89 (65.4) | 497 (70.5) |

| Energy drinks | 4 (2.2) | 15 (2.3) | - | 19 (2.7) |

| Juices | 54 (29.0) | 142 (21.7) | 41 (30.1) * | 155 (22.0) |

| Artificially flavored drinks | 15 (8.1) | 12 (1.8) | 3 (2.2) | 24 (3.4) |

| Coffee and tea | 123 (66.1) * | 361 (55.1) | 73 (53.7) | 411 (58.3) |

| Carbonated drinks and soda | 16 (8.6) | 79 (12.1) | 11 (8.1) | 84 (11.9) |

| No change | 28 (15.1) | 147(22.4) | 33 (24.4) | 142 (20.1) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

AlTarrah, D.; AlShami, E.; AlHamad, N.; AlBesher, F.; Devarajan, S. The Impact of Coronavirus COVID-19 Pandemic on Food Purchasing, Eating Behavior, and Perception of Food Safety in Kuwait. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8987. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168987

AlTarrah D, AlShami E, AlHamad N, AlBesher F, Devarajan S. The Impact of Coronavirus COVID-19 Pandemic on Food Purchasing, Eating Behavior, and Perception of Food Safety in Kuwait. Sustainability. 2021; 13(16):8987. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168987

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlTarrah, Dana, Entisar AlShami, Nawal AlHamad, Fatemah AlBesher, and Sriraman Devarajan. 2021. "The Impact of Coronavirus COVID-19 Pandemic on Food Purchasing, Eating Behavior, and Perception of Food Safety in Kuwait" Sustainability 13, no. 16: 8987. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168987

APA StyleAlTarrah, D., AlShami, E., AlHamad, N., AlBesher, F., & Devarajan, S. (2021). The Impact of Coronavirus COVID-19 Pandemic on Food Purchasing, Eating Behavior, and Perception of Food Safety in Kuwait. Sustainability, 13(16), 8987. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168987