Mandatory ESG Reporting and XBRL Taxonomies Combination: ESG Ratings and Income Statement, a Sustainable Value-Added Disclosure

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- XBRL taxonomies do not include ESG reports, but potentially only textual non-financial information.

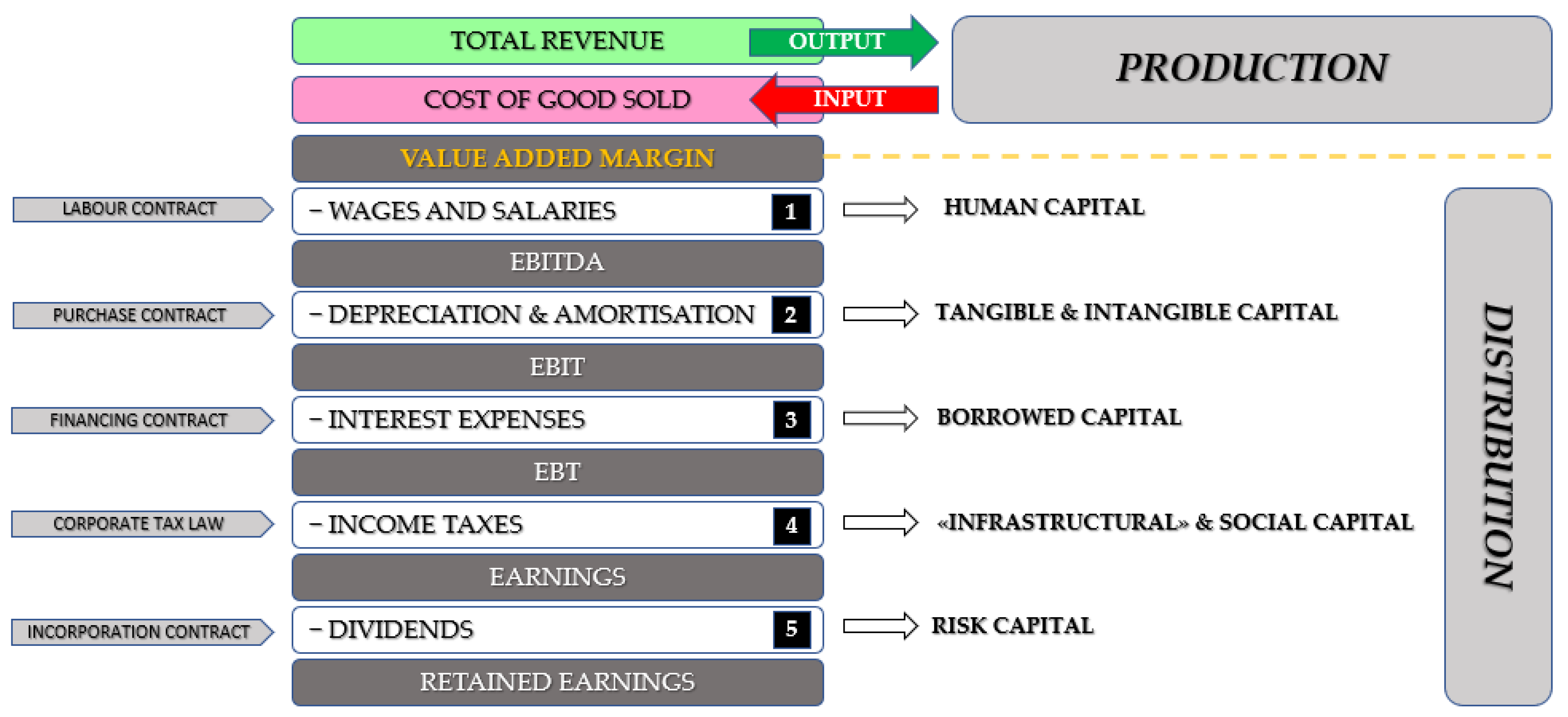

- Value-Added Income Statements can better serve sustainability purposes.

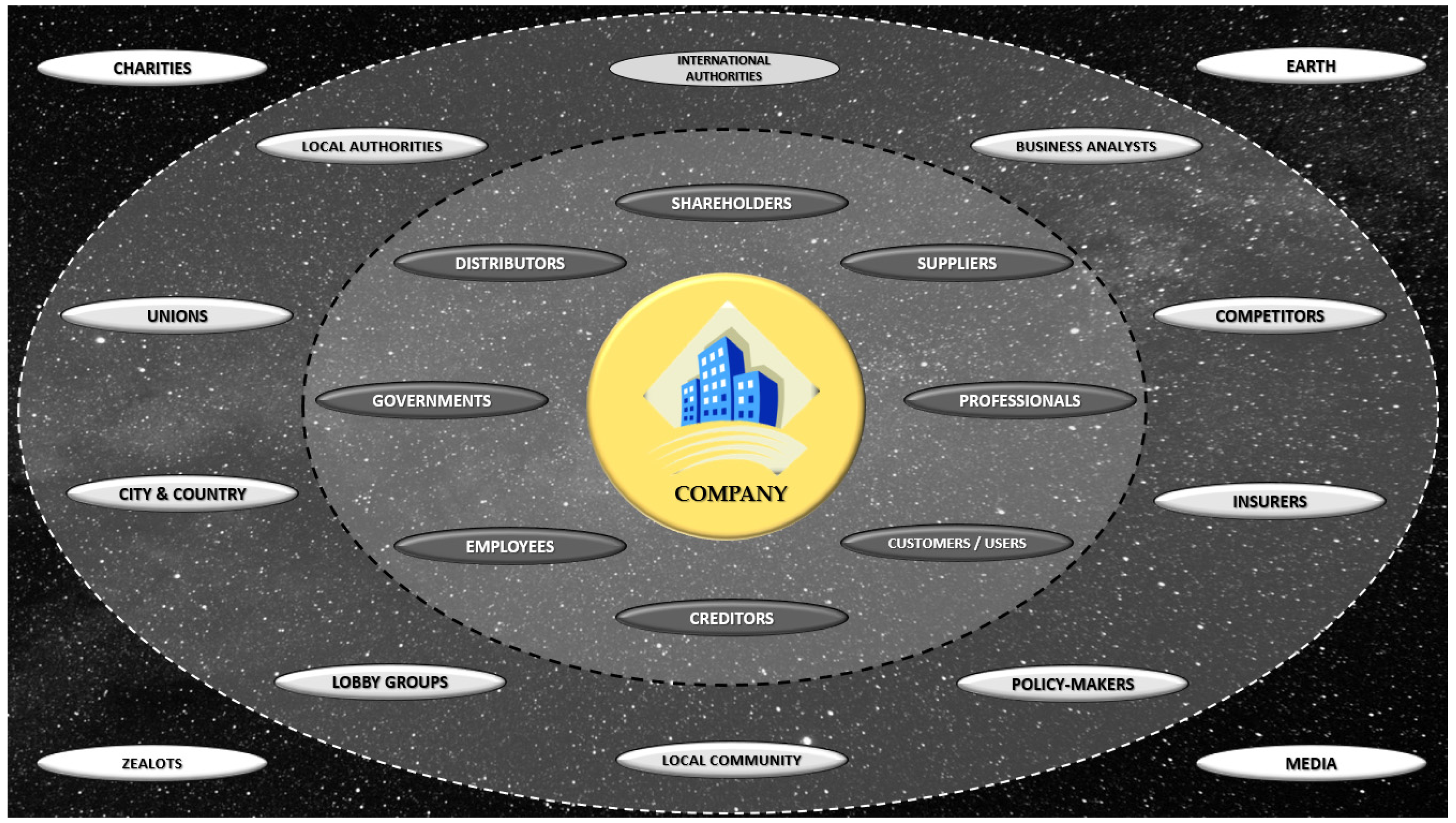

2.1. RQ1: Which Statement Can Better Represent the ESG Disclosure?

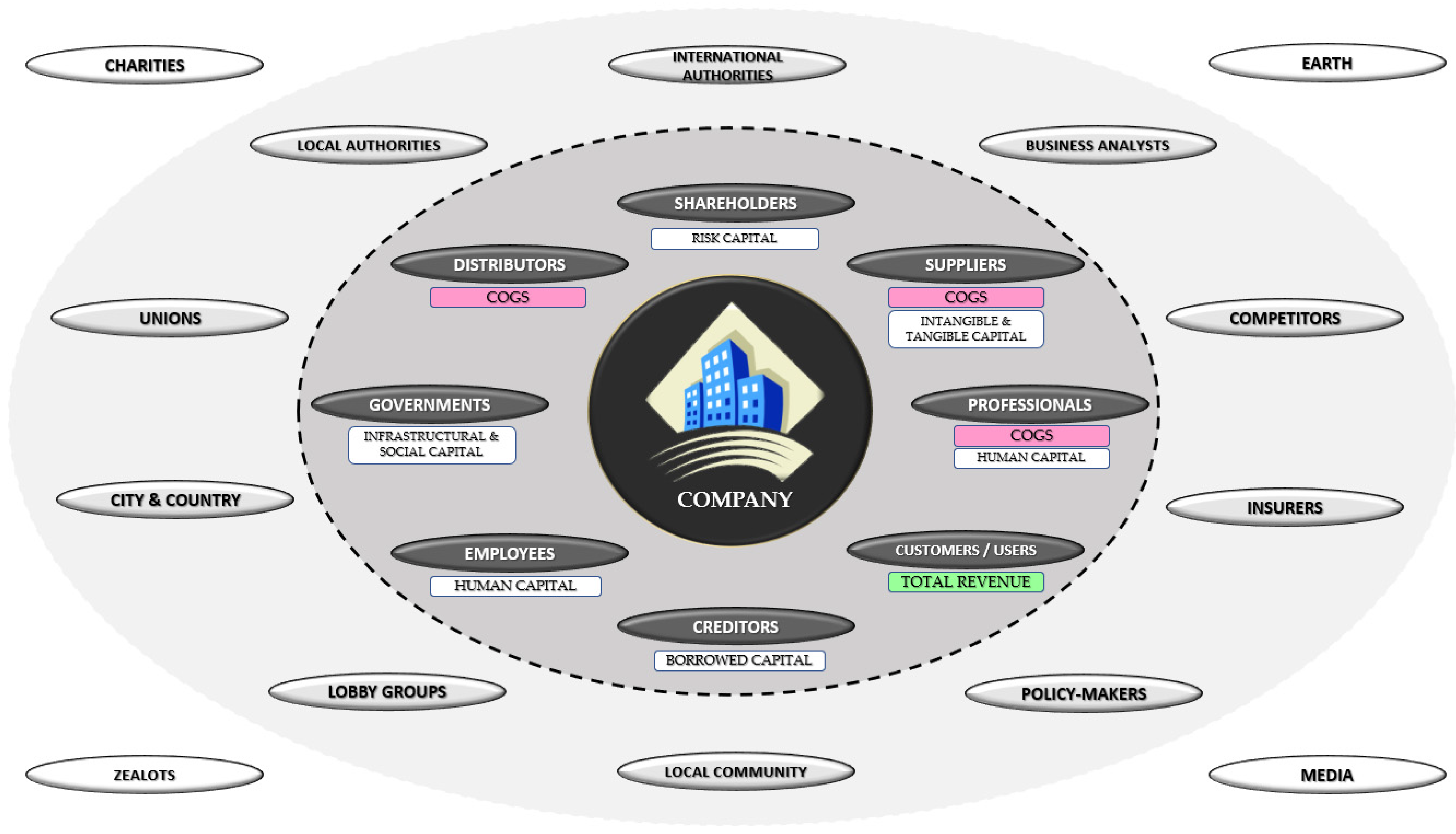

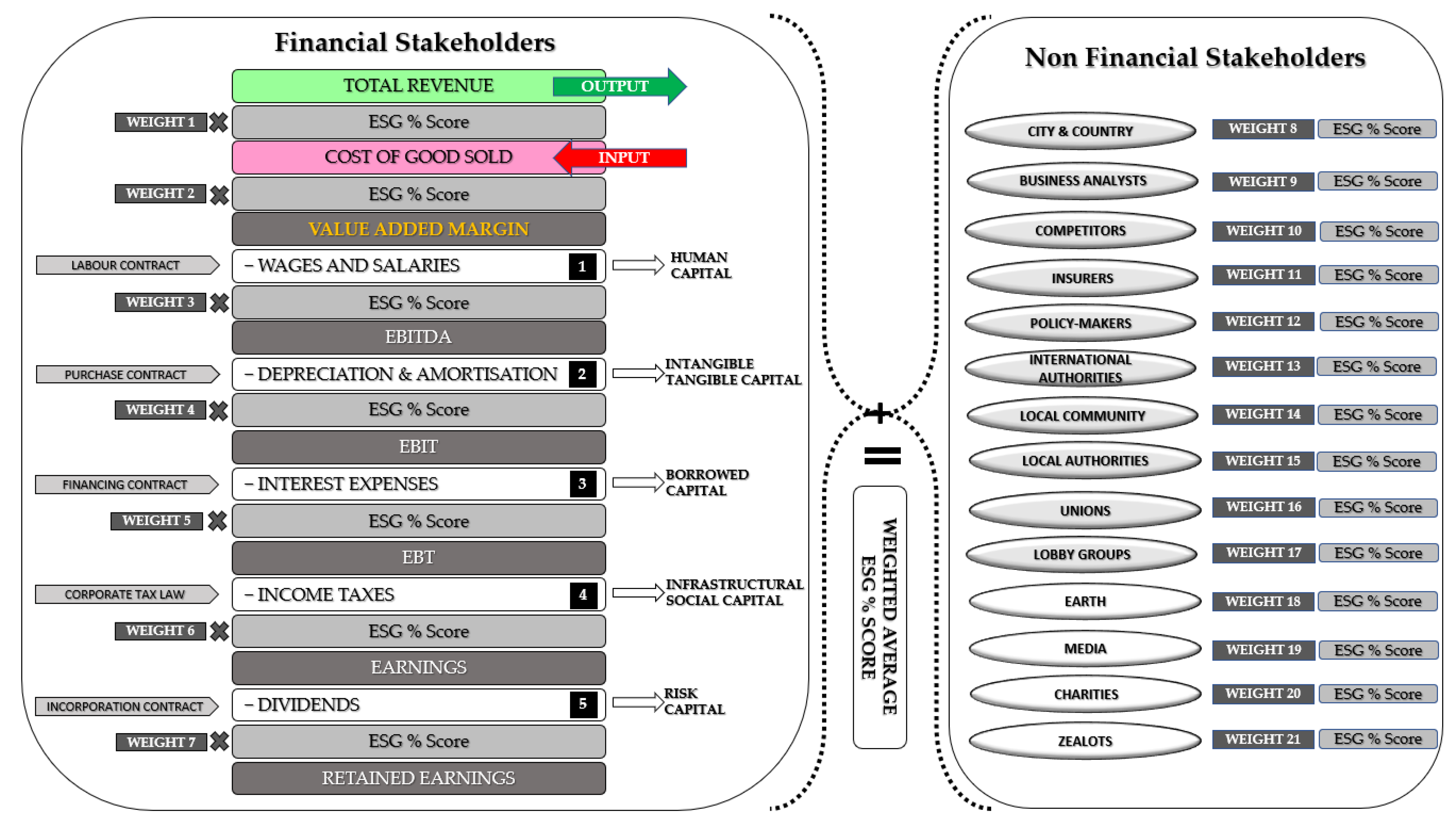

2.2. RQ2: How Can the VAIS Be Duly Re-Stated to Serve Sustainability Purposes?

2.3. RQ3: Is It Feasible to Develop an ESG-Based VAIS XBRL Template?

3. Framework and Results

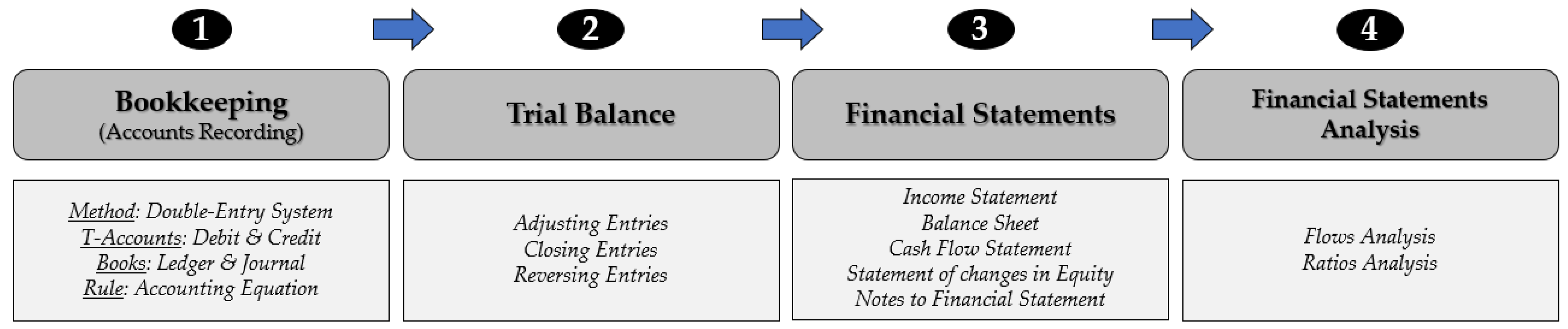

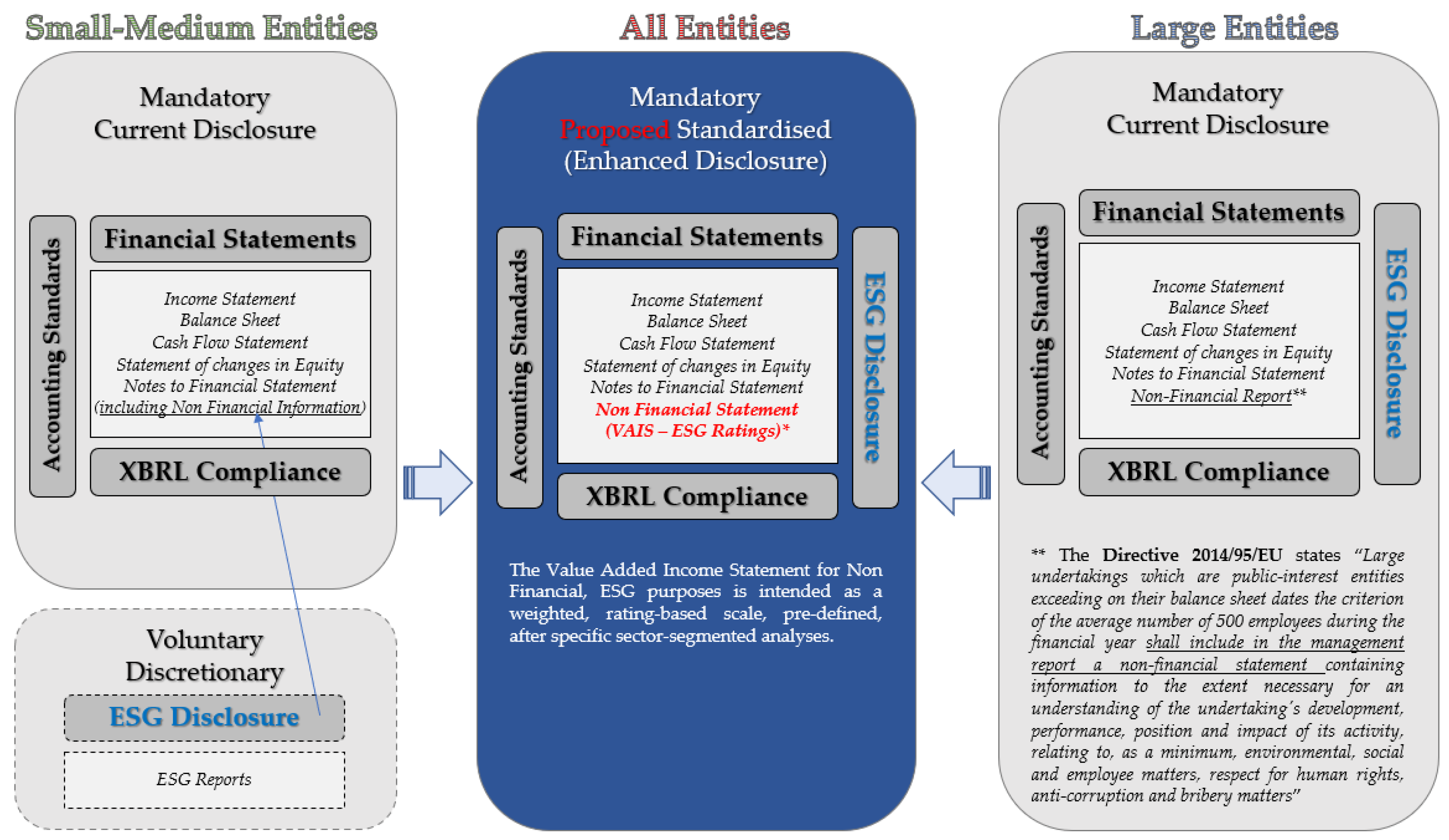

3.1. Accounting Standards, Regulations, and Financial Disclosure

- Listed companies;

- Banks and financial intermediaries subject to supervision;

- All companies issuing widespread financial instruments;

- Unlisted insurance companies with reference only to the consolidated financial statements;

- Listed insurance companies.

- Companies included in the consolidation of companies obliged to prepare consolidated financial statements in compliance with IAS;

- Companies subject to the obligation of preparation or included in a consolidated financial statement [41].

- The Statement of Financial Position (Balance Sheet);

- The Statement of Comprehensive Income (Income Statement);

- Statement of Changes in Shareholders’ Equity;

- The Cash Flow Statement, a document used to provide users of the financial statements with information on cash flows occurring during the year;

- The Notes with the function of adding and clarifying information can be obtained from the financial statements [42].

3.2. Sustainability—ESG Reports

3.3. Current ESG Rating Methodologies

3.4. XBRL Taxonomy and Value-Added Income Statement

3.4.1. Current Taxonomy

3.4.2. Value-Added Income Statement

3.4.3. Enhanced Taxonomy

| {330000} Statement of comprehensive income, profit or loss, by Added Value, ESG-based |

| {814000} Notes—ESG Ratings and Reporting |

| […] |

| <presentationLink xlink:type=“extended” xlink:role=“http://www....*” xlink:title=“[330000] Statement of comprehensive income, profit or loss, by added value, ESG-based”> |

| </presentationLink> |

| […] |

| <presentationLink xlink:type=“extended” xlink:role=“http://www....*” xlink:title=“[814000] Notes ESG Ratings and Reporting”> |

| </presentationLink> |

| […] |

| * “xlink” is intentionally left incomplete to avoid preferences |

3.4.4. Overcoming Implementation Challenges

- A specific expert panel should be appointed by the EU to identify the relevant stakeholders to be considered and the variables to be included in the model;

- Massive and extended testing, using the big data (already available) should lead to refined ESG rating systems, customised after suitable sector segmentation;

- Freeware, user-friendly (possibly automated) software should be provided to the entities to help minimising the implementation costs;

- Continuous update and model refinement.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

- -

- Flexible enough, in the weighting attribution;

- -

- Structured to ensure comparability and consistency;

- -

- XBRL-based to enforce its preparation according to an international standard;

- -

- Scoring-oriented to provide a systematic uniform result.

5. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Code | Description | Data Type |

|---|---|---|

| {110000} | General information about financial statements | Semi-structured |

| {210000} | Statement of financial position, current/non-current | structured |

| {220000} | Statement of financial position, order of liquidity | Structured |

| {310000} | Statement of comprehensive income, profit or loss, by function of expense | Structured |

| {320000} | Statement of comprehensive income, profit or loss, by nature of expense | Structured |

| {410000} | Statement of comprehensive income, OCI components presented net of tax | structured |

| {420000} | Statement of comprehensive income, OCI components presented before tax | Structured |

| {510000} | Statement of cash flows, direct method | Structured |

| {520000} | Statement of cash flows, indirect method | Structured |

| {610000} | Statement of changes in equity | Structured |

| {710000} | Statement of changes in net assets available for benefits | Structured |

| {800100} | Notes—Subclassifications of assets, liabilities and equities | Semi-structured |

| {800200} | Notes—Analysis of income and expense | Semi-structured |

| {800300} | Notes—Statement of cash flows, additional disclosures | Semi-structured |

| {800400} | Notes—Statement of changes in equity, additional disclosures | Semi-structured |

| {800500} | Notes—List of notes | Unstructured |

| {800600} | Notes—List of accounting policies | Unstructured |

| {810000} | Notes—Corporate information and statement of IFRS compliance | Unstructured |

| {811000} | Notes—Accounting policies, changes in accounting estimates and errors | Unstructured |

| {813000} | Notes—Interim financial reporting | Unstructured |

| {815000} | Notes—Events after reporting period | Unstructured |

| {816000} | Notes—Hyperinflationary reporting | Unstructured |

| {817000} | Notes—Business combinations | Unstructured |

| {818000} | Notes—Related party | Unstructured |

| {819100} | Notes—First time adoption | Unstructured |

| {822100} | Notes—Property, plant and equipment | Semi-structured |

| {822200} | Notes—Exploration for and evaluation of mineral resources | Semi-structured |

| {822390} | Notes—Financial instruments | Semi-structured |

| {823000} | Notes—Fair value measurement | Semi-structured |

| {823180} | Notes—Intangible assets | Semi-structured |

| {824180} | Notes—Agriculture | Unstructured |

| {824500} | Regulatory deferral accounts | Semi-structured |

| {825100} | Notes—Investment property | Semi-structured |

| {825480} | Notes—Separate financial statements | Semi-structured |

| {825700} | Notes—Interests in other entities | Semi-structured |

| {825900} | Notes—Non-current asset held for sale and discontinued operations | Semi-structured |

| {826380} | Notes—Inventories | Semi-structured |

| {827570} | Notes—Other provisions, contingent liabilities and contingent assets | Semi-structured |

| {831150} | Notes—Revenue from contracts with customers | Semi-structured |

| {831400} | Notes—Government grants | Semi-structured |

| {832410} | Notes—Impairment of assets | Semi-structured |

| {832610} | Notes—Leases | Semi-structured |

| {832900} | Notes—Service concession arrangements | Semi-structured |

| {834120} | Notes—Share-based payment arrangements | Semi-structured |

| {834480} | Notes—Employee benefits | Semi-structured |

| {835110} | Notes—Income taxes | Semi-structured |

| {836200} | Notes—Borrowing costs | Semi-structured |

| {836500} | Notes—Insurance contracts | Semi-structured |

| {836600} | Notes—Insurance contracts (IFRS 17) | Semi-structured |

| {838000} | Notes—Earnings per share | Semi-structured |

| {842000} | Notes—Effects of changes in foreign exchange rates | Semi-structured |

| {851100} | Notes—Cash Flow Statement | Semi-structured |

| {861000} | Notes—Analysis of other comprehensive income by item | Semi-structured |

| {861200} | Notes—Share capital, reserves and other equity interest | Semi-structured |

| {868200} | Notes—Rights to interests arising from decommissioning, restoration and environmental rehabilitation funds | Semi-structured |

| {868500} | Notes—Members’ shares in co-operative entities and similar instruments | Semi-structured |

| {871100} | Notes—Operating segments | Semi-structured |

| {880000} | Notes—Additional information | Semi-structured |

| {901000} | Axis—Retrospective application and retrospective restatement | Semi-structured |

| {901100} | Axis—Departure from requirement of IFRS | Semi-structured |

| {901500} | Axis—Creation date | Semi-structured |

| {903000} | Axis—Continuing and discontinued operations | Semi-structured |

| {904000} | Axis—Assets and liabilities classified as held for sale | Semi-structured |

| {913000} | Axis—Consolidated and separate financial statements | Semi-structured |

| {914000} | Axis—Currency in which information is displayed | Semi-structured |

| {915000} | Axis—Cumulative effect at date of initial application | Semi-structured |

| {990000} | Axis—Defaults | Semi-structured |

| Code | Description | Data Type |

|---|---|---|

| {110000} | General information about financial statements | Semi-structured |

| {210000} | Statement of financial position, current/non-current | Structured |

| {220000} | Statement of financial position, order of liquidity | Structured |

| {310000} | Statement of comprehensive income, profit or loss, by function of expense | Structured |

| {320000} | Statement of comprehensive income, profit or loss, by nature of expense | Structured |

| {330000} | Statement of comprehensive income, profit or loss, by Added Value, ESG-based | Structured |

| {410000} | Statement of comprehensive income, OCI components presented net of tax | structured |

| {420000} | Statement of comprehensive income, OCI components presented before tax | Structured |

| {510000} | Statement of cash flows, direct method | Structured |

| {520000} | Statement of cash flows, indirect method | Structured |

| {610000} | Statement of changes in equity | Structured |

| {710000} | Statement of changes in net assets available for benefits | Structured |

| {800100} | Notes—Subclassifications of assets, liabilities and equities | Semi-structured |

| {800200} | Notes—Analysis of income and expense | Semi-structured |

| {800300} | Notes—Statement of cash flows, additional disclosures | Semi-structured |

| {800400} | Notes—Statement of changes in equity, additional disclosures | Semi-structured |

| {800500} | Notes—List of notes | Unstructured |

| {800600} | Notes—List of accounting policies | Unstructured |

| {810000} | Notes—Corporate information and Statement of IFRS compliance | Unstructured |

| {811000} | Notes—Accounting policies, changes in accounting estimates and errors | Unstructured |

| {813000} | Notes—Interim financial reporting | Unstructured |

| {814000} | Notes—ESG Ratings and Reporting | Semi-structured |

| {815000} | Notes—Events after reporting period | Unstructured |

| {816000} | Notes—Hyperinflationary reporting | Unstructured |

| {817000} | Notes—Business combinations | Unstructured |

| {818000} | Notes—Related party | Unstructured |

| {819100} | Notes—First time adoption | Unstructured |

| {822100} | Notes—Property, plant and equipment | Semi-structured |

| {822200} | Notes—Exploration for and evaluation of mineral resources | Semi-structured |

| {822390} | Notes—Financial instruments | Semi-structured |

| {823000} | Notes—Fair value measurement | Semi-structured |

| {823180} | Notes—Intangible assets | Semi-structured |

| {824180} | Notes—Agriculture | Unstructured |

| {824500} | Regulatory deferral accounts | Semi-structured |

| {825100} | Notes—Investment property | Semi-structured |

| {825480} | Notes—Separate financial statements | Semi-structured |

| {825700} | Notes—Interests in other entities | Semi-structured |

| {825900} | Notes—Non-current asset held for sale and discontinued operations | Semi-structured |

| {826380} | Notes—Inventories | Semi-structured |

| {827570} | Notes—Other provisions, contingent liabilities and contingent assets | Semi-structured |

| {831150} | Notes—Revenue from contracts with customers | Semi-structured |

| {831400} | Notes—Government grants | Semi-structured |

| {832410} | Notes—Impairment of assets | Semi-structured |

| {832610} | Notes—Leases | Semi-structured |

| {832900} | Notes—Service concession arrangements | Semi-structured |

| {834120} | Notes—Share-based payment arrangements | Semi-structured |

| {834480} | Notes—Employee benefits | Semi-structured |

| {835110} | Notes—Income taxes | Semi-structured |

| {836200} | Notes—Borrowing costs | Semi-structured |

| {836500} | Notes—Insurance contracts | Semi-structured |

| {836600} | Notes—Insurance contracts (IFRS 17) | Semi-structured |

| {838000} | Notes—Earnings per share | Semi-structured |

| {842000} | Notes—Effects of changes in foreign exchange rates | Semi-structured |

| {851100} | Notes—Cash Flow Statement | Semi-structured |

| {861000} | Notes—Analysis of other comprehensive income by item | Semi-structured |

| {861200} | Notes—Share capital, reserves and other equity interest | Semi-structured |

| {868200} | Notes—Rights to interests arising from decommissioning, restoration and environmental rehabilitation funds | Semi-structured |

| {868500} | Notes—Members’ shares in co-operative entities and similar instruments | Semi-structured |

| {871100} | Notes—Operating segments | Semi-structured |

| {880000} | Notes—Additional information | Semi-structured |

| {901000} | Axis—Retrospective application and retrospective restatement | Semi-structured |

| {901100} | Axis—Departure from requirement of IFRS | Semi-structured |

| {901500} | Axis—Creation date | Semi-structured |

| {903000} | Axis—Continuing and discontinued operations | Semi-structured |

| {904000} | Axis—Assets and liabilities classified as held for sale | Semi-structured |

| {913000} | Axis—Consolidated and separate financial statements | Semi-structured |

| {914000} | Axis—Currency in which information is displayed | Semi-structured |

| {915000} | Axis—Cumulative effect at date of initial application | Semi-structured |

| {990000} | Axis—Defaults | Semi-structured |

References

- EU–Press Release. Commission Welcomes Provisional Agreement on the European Climate Law. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_1828 (accessed on 21 April 2021).

- EU Extends Mandatory Sustainability Reporting to 50,000 Companies. Available online: https://www.esgtoday.com/eu-extends-mandatory-sustainability-reporting-to-50000-companies/ (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Hoang, T. The role of the integrated reporting in raising awareness of environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) performance. In Stakeholders, Governance and Responsibility. Emerald Publishing Limited; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Escrig-Olmedo, E.; Muñoz-Torres, M.J.; Fernandez-Izquierdo, M.A. Socially responsible investing: Sustainability indices, ESG rating and information provider agencies. Int. J. Sustain. Econ. 2010, 2, 442–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Rietz, S. Information vs knowledge: Corporate accountability in environmental, social, and governance issues. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2018, 31, 586–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Băndoi, A.; Bocean, C.G.; Del Baldo, M.; Mandache, L.; Mănescu, L.G.; Sitnikov, C.S. Including sustainable reporting practices in corporate management reports: Assessing the impact of transparency on economic performance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, J.; McKinnon, M.; Van der Byl, C. Green gaps: Firm ESG disclosure and financial institutions’ reporting Requirements. J. Sustain. Res. 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, N.E.; Ohsowski, B. Identifying worldviews on corporate sustainability: A content analysis of corporate sustainability reports. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 128–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosati, F.; Faria, L.G. Addressing the SDGs in sustainability reports: The relationship with institutional factors. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 215, 1312–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diouf, D.; Boiral, O. The quality of sustainability reports and impression management. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2017, 30, 643–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoitash, R.; Hoitash, U.; Morris, L. eXtensible Business reporting language: A review and directions for future research. XBRL Res. 2020, 1, 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Beretta, V.; Demartini, M.C.; Lico, L.; Trucco, S. A tone analysis of the non-financial disclosure in the automotive industry. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corporate Sustainability Reporting. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/company-reporting-and-auditing/company-reporting/corporate-sustainability-reporting_en (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Faccia, A.; Manni, F. Financial Accounting: Text and Cases; Aracne Editrice: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mohana, R.P. Financial Statement Analysis and Reporting; PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd.: New Delhi, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- DeGennaro, M. An economic comparison of US GAAP and IFRS. J. Int. Bus. Law 2017, 16, 7. [Google Scholar]

- An Introduction to XBRL. Available online: https://www.xbrl.org/the-standard/what/an-introduction-to-xbrl/ (accessed on 11 June 2020).

- Apostolou, A.K.; Nanopoulos, K.A. Interactive financial reporting using XBRL: An overview of the global markets and Europe. Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2009, 6, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weglarz, G. Two worlds of data unstructured and structured. Inf. Manag. 2004, 14, 19. [Google Scholar]

- O’Riain, S.; Curry, E.; Harth, A. XBRL and open data for global financial ecosystems: A linked data approach. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, E.; Wang, W.M.; Cai, L.; Cheung, C.F.; Lee, W.B. Knowledge-based extraction of intellectual capital-related information from unstructured data. Expert Syst. Appl. 2014, 41, 1315–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efimova, O.; Rozhnova, O.; Gorodetskaya, O. Xbrl as a tool for integrating financial and non-financial reporting. In The 2018 International Conference on Digital Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Seele, P. Digitally unified reporting: How XBRL-based real-time transparency helps in combining integrated sustainability reporting and performance control. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 136, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McLeay, S. Value added: A comparative study. Account. Organ. Soc. 1983, 8, 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabol, A.; Sverer, F. A review of the economic value added literature and application. UTMS J. Econ. 2017, 8, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sustainalytics’ ESG Risk Ratings Offer Clear Insights into the ESG Risks of Companies. Available online: https://www.sustainalytics.com/esg-ratings/ (accessed on 11 June 2020).

- What Is an MSCI ESG Rating? Available online: https://www.msci.com/our-solutions/esg-investing/esg-ratings (accessed on 11 June 2020).

- Cao, M.; Chychyla, R.; Stewart, T. Big data analytics in financial statement audits. Account. Horiz. 2015, 29, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, T.R. Data analytics for financial statement audits. Audit. Anal. 2015, 105–128. Available online: https://www.aicpa.org/content/dam/aicpa/interestareas/frc/assuranceadvisoryservices/downloadabledocuments/auditanalytics-lookingtowardfuture.pdf#page=130 (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Patibandla, R.L.; Veeranjaneyulu, N. Survey on clustering algorithms for unstructured data. In Intelligent Engineering Informatics; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 421–429. [Google Scholar]

- Das, T.K.; Kumar, P.M. Big data analytics: A framework for unstructured data analysis. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2013, 5, 153. [Google Scholar]

- Syed, A.; Gillela, K.; Venugopal, C. The future revolution on big data. Future 2013, 2, 2446–2451. [Google Scholar]

- Gandomi, A.; Haider, M. Beyond the hype: Big data concepts, methods, and analytics. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2015, 35, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vasarhelyi, M.A.; Chan, D.Y.; Krahel, J.P. Consequences of XBRL standardization on financial statement data. J. Inf. Syst. 2012, 26, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruppo Bilancio Sociale. 2020. Available online: http://www.gruppobilanciosociale.org/ (accessed on 5 November 2020).

- Altman, E.I. A fifty-year retrospective on credit risk models, the Altman Z-score family of models and their applications to financial markets and managerial strategies. J. Credit. Risk 2018, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Le Leslé, V.; Avramova, M.S. Revisiting Risk-Weighted Assets; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, C.; Oikonomou, I. The effects of environmental, social and governance disclosures and performance on firm Value: A review of the literature in accounting and finance. Br. Account. Rev. 2018, 50, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, Y. Stakeholders expectations for CSR-related corporate governance disclosure: Evidence from a developing country. Asian Rev. Account. 2021, 29, 97–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Trimble, M. The Historical and current status of global ifrs adoption: Obstacles and opportunities for researchers. Int. J. Account. 2020, 2250001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU Regulation, n. 1606/2002. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32002R1606 (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Barker, R.; Teixeira, A. Gaps in the IFRS conceptual framework. Account. Eur. 2018, 15, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission Delegated Regulation (EU). 04.06.2021. Supplementing Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council by Establishing the Technical Screening Criteria for Determining the Conditions under Which an Economic Activity Qualifies as Contributing Substantially to Climate Change Mitigation or Climate Change Adaptation and for Determining Whether That Economic Ac-tivity Causes no Significant Harm to Any of the Other Environmental Objectives. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/ec9fae45-2b5e-11eb-87b7-01aa75ed71a1/language-en#:~:text=%E2%80%A6%2F...-,supplementing%20Regulation%20(EU)%202020%2F852%20of%20the%20European%20Parliament,change%20adaptation%20and%20for%20determining (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Bloomberg to Offer MSCI ESG Research Data on the Bloomberg Terminal. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/company/press/bloomberg-to-offer-msci-esg-research-data-on-the-bloomberg-terminal/ (accessed on 11 June 2020).

- IASB. IFRS Taxonomy Illustrated a View of the IFRS Taxonomy 2021 (Organised by Financial Statement); IASB: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, Á.I.; Caminero, T. Application of text mining to the analysis of climate-related disclosures. Banco Esp. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faccia, A.; Mataruna-Dos-Santos, L.J.; Munoz Helù, H.; Range, D. Measuring and monitoring sustainability in listed european football clubs: A value-added reporting perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruppo Bilancio Sociale. 2020. Available online: http://www.gruppobilanciosociale.org/pubblicazioni (accessed on 11 June 2020).

- Mei, O.G. Metodologie Quantitative di Determinazione del Valore Aggiunto Aziendale; Libreria Goliardica: Trieste, Italy, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Gabrovec Mei, O.; Vitezi, N. Social and environmental responsibility–accountability and reporting in the EU. In Proceedings of the IIA International Conference Economic System of the European Union and Adjustment of the Republic of Croatia, Lovran, Croatia, 8 April 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Manni, F. Il bilancio sociale nello sport professionistico. Econ. Aziend. Online 2012, 12, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Manni, F. Riflessioni sul bilancio sociale nel contesto non profit. Econ. Aziend. Online 2010, 1, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Manni, F. Responsabilità Sociale e Informazione Esterna D’impresa: Problemi, Esperienze e Prospettive del Bilancio Sociale; G. Giappichelli: Turin, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Manni, F.; Faccia, A. The business going concern: Financial return and social expectations. In Sustainable Development and Social Responsibility; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 1, pp. 201–213. [Google Scholar]

- Altman, E.I. The Use of Credit Scoring Models and the Importance of a Credit Culture; Stern School of Business, New York University: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Krisko, A. The role of resistance in incorporating XBRL into financial reporting practices. Int. J. Account. Econ. Stud. 2017, 5, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pinsker, R.; Li, S. Costs and benefits of XBRL adoption: Early evidence. Commun. ACM 2008, 51, 47–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannon, N.J. Does XBRL cost too much? Strateg. Financ. 2006, 1, 59–61. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Faccia, A.; Manni, F.; Capitanio, F. Mandatory ESG Reporting and XBRL Taxonomies Combination: ESG Ratings and Income Statement, a Sustainable Value-Added Disclosure. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8876. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168876

Faccia A, Manni F, Capitanio F. Mandatory ESG Reporting and XBRL Taxonomies Combination: ESG Ratings and Income Statement, a Sustainable Value-Added Disclosure. Sustainability. 2021; 13(16):8876. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168876

Chicago/Turabian StyleFaccia, Alessio, Francesco Manni, and Fabian Capitanio. 2021. "Mandatory ESG Reporting and XBRL Taxonomies Combination: ESG Ratings and Income Statement, a Sustainable Value-Added Disclosure" Sustainability 13, no. 16: 8876. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168876

APA StyleFaccia, A., Manni, F., & Capitanio, F. (2021). Mandatory ESG Reporting and XBRL Taxonomies Combination: ESG Ratings and Income Statement, a Sustainable Value-Added Disclosure. Sustainability, 13(16), 8876. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168876