Abstract

Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) is a technique to establish the interrelationships between elements of interest in a specific domain through experts’ knowledge of the context of the elements. This technique has been applied in numerous domains and the list continues to grow due to its simplistic concept, while sustainability has taken the lead. The partially automated or manual application of this technique has been prone to errors as witnessed in the literature due to a series of mathematical steps of higher-order computing complexity. Therefore, this work proposes to develop an end-to-end graphical software, SmartISM, to implement ISM technique and MICMAC (Matrice d’Impacts Croisés Multiplication Appliquée á un Classement (cross-impact matrix multiplication applied to classification)), generally applied along with ISM to classify variables. Further, a scoping review has been conducted to study the applications of ISM in the previous studies using Denyer and Tranfield’s (2009) framework and newly developed SmartISM. For the development of SmartISM, Microsoft Excel software has been used, and relevant algorithms and VBA (Visual Basic for Applications) functions have been illustrated. For the transitivity calculation the Warshall algorithm has been used and a new algorithm reduced conical matrix has been introduced to remove edges while retaining the reachability of variables and structure of digraph in the final model. The scoping review results demonstrate 21 different domains such as sustainability, supply chain and logistics, information technology, energy, human resource, marketing, and operations among others; numerous types of constructs such as enablers, barriers, critical success factors, strategies, practices, among others, and their numbers varied from 5 to 32; number of decision makers ranged between 2 to 120 with a median value of 11, and belong to academia, industry, and/or government; and usage of multiple techniques of discourse and survey for decision making and data collection. Furthermore, the SmartISM reproduced results show that only 29 out of 77 studies selected have a correct application of ISM after discounting the generalized transitivity incorporation. The outcome of this work will help in more informed applications of this technique in newer domains and utilization of SmartISM to efficiently model the interrelationships among variables.

1. Introduction

Every discipline is expanding its frontier and multiple disciplinary approaches have become essential to solve complex problems. This leads to the study of a large number of constructs of interests simultaneously. These constructs may have been identified in theory or practice. Warfield [1,2,3,4] in the 1970’s developed a technique to establish an interrelationship model between variables known as interpretive structural modeling (ISM). The holistic picture of important constructs in the structured form derived from ISM technique helps the practitioners to solve the problem effectively. This technique is widely used due to its simplistic procedure and profound value addition in problem solving in different domains.

ISM helps in representing partial, fragmented, and distributed knowledge into integrated, interactive, and actionable knowledge. This technique is therefore particularly useful for the areas that are inherently multidisciplinary, such as sustainability. The discipline of sustainability ensures the performance in three areas: economic, social, and environmental, termed as triple bottom line (TBL) [5], while the world undergoes development. Additionally, the literature shows the maximum number of applications of this technique in the area of sustainability.

The search with the quoted keywords of “interpretive structural modeling” on the single database of Scopus yielded 5184 documents. There is an exponential growth in the usage of this technique from 2007 onward; prior to this year articles are around 10 each year starting from 1974. For the year 2007, 46 documents are listed and the numbers are exponentially increasing each successive year to 1200 documents in the year of 2020. With around 36% contribution in articles, India is leading the application of ISM, followed by China, USA, UK, and Iran. Together these five countries contribute around 71% of total articles. This technique is being used in many disciplines in decreasing order, namely business, engineering, computer science, decision science, environmental science, social science, and others.

ISM helps in modeling the variables and brings out the existing interrelationship structure among them. It helps a group of people or decision makers to debate and share their knowledge and achieve consensus on the relationships among the variables. The participants can share their views without any knowledge of mathematical complexity involved in the underlying steps. A computerized program may automate all the graphical and algebraic computation and convert their inputs into a pictorial model consisting of variables along with the relationships among them. The ISM process does not add any information [6] but brings in structural value [7].

In the same time period of the 1970’s, another technique known as MICMAC (Matrice d’Impacts Croisés Multiplication Appliquée á un Classement (cross-impact matrix multiplication applied to classification)) was developed by J. C. Duperrin and M. Godet [8]. MICMAC helps in classification of the variables into one of the four categories, namely dependent, independent, linkage, and autonomous variables. ISM coupled with MICMAC becomes a strong tool to visualize the structure of variables along with the interrelationships between them. ISM is also used in several multi criteria decision making (MCDM) techniques such as analytical hierarchy process (AHP) [9], analytic network process (ANP) [10,11,12], technique for order of preference by similarity to ideal solution (TOPSIS) [13,14], decision-making trial, evaluation laboratory (DEMATEL) [15,16], and others.

Implementation of this technique and conduction of brainstorming sessions with experts in previous studies [17,18] led to identification of some key challenges such as variables’ identification, selection of decision makers and method of decision making, and unavailability of end-to-end software for ISM and MICMAC. Furthermore, the literature shows erroneous applications of steps of ISM such as wrong reachability matrix [19,20,21,22], wrong transitivity calculations [9,13,16,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37], incorrect level partitioning and wrong structure of the model [31,38,39,40,41,42], and incorrect addition [11,14,43,44,45,46,47,48] or reduction [49,50,51,52] of edges affecting the reachability of variables. An error in an earlier step generally leads to an error in subsequent steps. Similarly, the wrong calculation of transitivity leads to wrong MICMAC diagrams. Therefore, there exists some important issues in implementation of this technique, namely identification of variables, decision makers, expertise and experience of decision makers, method of decision making, and computerization of the steps of ISM. Previous ISM reviews [53,54,55] don’t critically analyze the steps of ISM applications in the articles. Similarly, although some automation of the ISM technique has been provided earlier [56,57], there does not exist any end-to-end graphical software that may help in applying this technique and allow the decision makers to focus on sharing knowledge and iterate the ISM technique until a high-confidence consensus model is arrived at. These challenges set the objectives of this research as follows:

- Development of SmartISM, a software tool for ISM and MICMAC using Microsoft Excel and VBA.

- Scoping review of applications of ISM on existing studies to identify application domains, types and numbers of variables studied, composition of decision makers, decision making and data collection techniques, and accuracy of ISM application using SmartISM.

The remainder of the paper is organized into the following sections: literature review, research methodology, development of SmartISM using Microsoft Excel, results, discussion, and conclusion.

2. Literature Review

There are numerous studies in the literature that illustrate the ISM technique. They can be summarized into the seven steps approach with an additional eighth step for MICMAC analysis, as given in the following subsection. The next subsection illustrates the existing available automation of the ISM. The last subsection presents some studies that have reviewed the implementations of ISM.

2.1. ISM and MICMAC Techniques

The interpretive structural modelling (ISM) can be defined as constructs’ directional structuring technique based on contextual interrelationships defined by domain experts, utilizing computerized conversion of relations into a pictorial model using matrix algebra and graph theory. It may be explained in the series of steps as follows, which will assist in automating all the processes of the ISM technique.

2.1.1. Elements or Constructs or Variables

Identification of elements or constructs of the subject being studied is the most important of all activities. Similarly, the establishment of their definition along with the theoretical boundaries or scope is very critical. Elements must be explained with the details of their definition, objectives, and possible indications or measurements. These elements are generally identified by literature review, expert opinions, and/or surveys. Some of the unique approaches have been use of thematic analysis [58], upper echelon theory [11], contingency theory [59], content analysis [52], strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT) analysis [30], idea engineering workshop [40,60], and Delphi technique [37,61]. One study [42] has defined the source, understanding, and interpretation for each variable.

2.1.2. Decision Makers (DMs)

DMs play a very significant role in ISM as the whole process and outcome are dependent upon their input. There are three important aspects for the selection of a group of DMs such as size, expertise, and diversity. The group of DMs should be representative of all of the stakeholders in the domain of the problem. They should have sound experience of domain and expert level knowledge of variables being studied. The literature shows the number of DMs ranging between 2 [62,63] to 120 [64] with a median value of 11, and very few studies [16,30,41,65] have taken DMs from academia, industry, and government together.

2.1.3. Structural Self-Interaction Matrix (SSIM)

Elements or constructs are interrelated with one of the four relations such as x influences y, y influences x, x and y mutually influence each other, or x and y are unrelated. These relations are almost universally represented by ‘V’, ‘A’, ‘X’, and ‘O’ characters respectively in the SSIM. These relationships are assigned by DMs based on contextual relationships during pairwise comparison on variables. The number of comparisons is nC2 (mathematical combination), where n is the number of variables in the domain of study. Finally, an n by n matrix is formed with nC2 cells filled with A, V, X, and O symbols and the remaining cells are blank. Most studies have used these standard symbols except few such as [35]. As this is the basic matrix and required for all other steps therefore has been documented in most of the studies except few such as [15,66].

2.1.4. Reachability Matrix (RM) and Final Reachability Matrix (FRM)

RM is the representation of SSIM in binary form. V, A, X, and O symbols of SSIM are replaced with 1, 0, 1, and 0, digits respectively. At their transposed positions by row with column and column with row, 0, 1, 1, and 0 digits are placed, respectively. The constructs are assumed to influence self, so ones are placed at the diagonal positions. The resultant RM is checked for transitive relations. Transitivity is the basic assumption in the ISM such as if variable x influences y and y influences z then x will influence z transitively. This is second-order or two-hop transitivity whereas generalized transitivity means x is related to z through one or more variables. The transitive relations hence identified are represented in the RM with 1*s to distinguish from original 1s and the resulting matrix is known as FRM. FRM also consists of driving and dependence powers of each variable by counting 1s and 1*s in rows and columns respectively. Very few studies mention usage of some software for transitivity calculations such as [56,57]. However, one of the most frequent reasons for incorrect ISM calculations have been wrong transitivity calculations, such as in studies [9,13,16,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Therefore, this study proposes the use of an established Warshall algorithm [67] for transitivity calculations.

2.1.5. Level Partitioning

This is a very important step to develop the hierarchical directional structure among the variables. Reachability, antecedent, and intersection sets are derived for all the variables from the FRM. For a specific variable, a reachability set consists of itself and all the variables it influences, and an antecedent set consists of itself and all the variables influencing it. Thereafter, the intersection set of reachability and antecedent set is calculated. Variables having the same reachability and intersection sets are given the top rank and are removed for the next iteration and the process is repeated until all variables are ranked. Some studies such as [31,38,39,40,41,42] in the literature had incorrect leveling for variables.

2.1.6. Conical Matrix (CM) and Digraph

CM is row and column wise ordered FRM based on ranks or levels of variables identified in the level partitioning step. Further the levels of each variable are also recorded at the end of row and column in CM. This matrix helps in drawing the digraph to get the first visual output of the hierarchical directional structure of variables. Circular nodes are drawn with variable numbers. Further they are connected with directional edges based upon 1s or 1*s in the CM between pairs of variables. Fewer studies have mentioned CM and digraph [12,20,27,35,65,68,69,70], as the digraph resembles the final model with a lesser number of edges. The importance of the digraph further goes down in automatic calculation of transitivity.

2.1.7. Reduced Conical Matrix (RCM) and Final ISM Model

Digraph is converted into a final model by replacing the node numbers with names of the variables and representing nodes in the rectangular shapes. Moreover, efforts are made to remove maximum edges from digraph while maintaining the levels and structure of variables and reachability of variables. This is done to improve the readability of the final model. Several studies have committed mistakes at this step either by adding extra edges [11,14,43,44,45,46,47,48] or omitting edges [49,50,51,52] that have affected the reachability of the variables. Therefore, a new algorithm, reduced conical matrix (RCM), has been devised to remove maximum possible edges without affecting structure and reachability of variables, as explained in the fourth section. This RCM is used for making the final ISM model. The final model may further be subjected to validations by different means such as review by DMs, interviews from different sets of participants, or statistical validations.

2.1.8. MICMAC

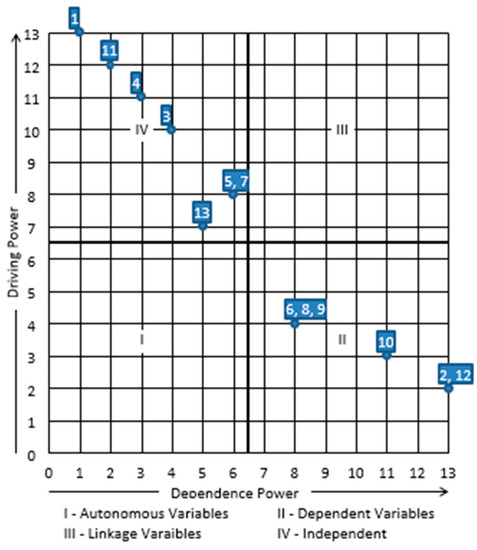

MICMAC (Matrice d’Impacts Croisés Multiplication Appliquée á un Classement (cross-impact matrix multiplication applied to classification)) in the simplest terms is a variable classification technique. Variables are mapped onto a two-dimensional grid based on their dependence and driving power values, represented on horizontal and vertical axes respectively. The range of these values is between 1 and total number of variables and the axes are bifurcated at mid-points, resulting in four quadrants numbered anti clockwise. These quadrants classify variables into autonomous, dependent, linkage, and independent categories. The autonomous variables are not connected with the remaining system of variables whereas linkage variables are sensitive and strongly connected with independent and dependent variables. The final hierarchical ISM model coupled with the MICMAC analysis greatly improves the understanding of variables. Therefore, most studies have carried out MICMAC analysis except few such as [19,39,47,71,72].

2.2. Implementation of ISM

As originally proposed by Warfield [1,2,3,4], the ISM requires its steps to be executed with the assistance of a computer [6]. Some of the more recent studies demonstrate specialized software or routines being developed for ISM. The article [56] mentions the development of the ISM software package in R software. This software package takes the SSIM input in the comma separated (.csv) excel file and provides two outputs in excel file format, namely, “ISM_Matrix” for FRM step to incorporate transitivity calculations and “ISM_Output” for partitioning step to identify the levels of the variables. Similarly, some studies such as [57] have used MATLAB software to calculate the FRM and partitioning steps. The previous studies have attempted to automate FRM and partitioning steps, leading to partial automation of ISM. As pointed out earlier in absence of automation, the final model may introduce errors in edges regardless of correct FRM and leveling, leading to wrong reachability of variables. Further, having all the steps being carried out automatically shows the prompt results to researchers and decision makers for further possible iterations. Therefore, there exists a need to develop an end-to-end graphical software to implement ISM and MICMAC and identify the required algorithms for it.

2.3. Assessment of ISM Applications

The ISM technique is being applied in a range of domains [53,54,55]. The review article [54] provides 10 different application domains for ISM. It further provides additional parameters such as integration with other MCDM approaches. Similarly the review article [55] identified ISM applications in 14 domains without industry or organizations, 20 industrial sectors, and 4 other areas. Furthermore, among other characteristics, it mentions integration with other MCDM approaches, and the presence of constructs for cost and/or quality. These reviews haven’t focused on operationalization of ISM technique. Therefore, there exists a gap to identify the methodology of steps of applications of ISM in the existing articles such as nature and number of variables, compositions of DMs, decision making and data collection techniques, and accuracy of ISM results.

3. Research Methodology

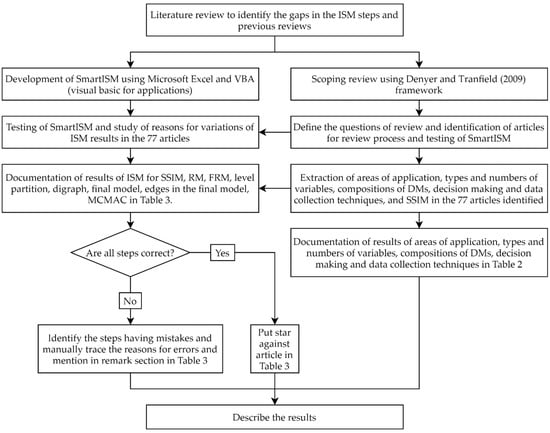

This study addresses two objectives, firstly the development of SmartISM for the implementation of ISM, as explained in the following section. The second objective is the scoping review of literature to identify the scope of ISM and MICMAC applications and the assessment of applications of ISM using SmartISM tool. For the scoping review the five-step framework of Denyer and Tranfield (2009) [73] has been adopted as explained in the following paragraphs, Figure 1. The review process also generated the data necessary for the assessment of application of ISM using SmartISM.

Figure 1.

Research Methodology.

Step I: Question formulation: Formulating questions requires identification of context, interventions, mechanisms, and outcomes. In this study, context is considered to be domain, and decision makers; interventions are variables of interest in problem domain; mechanisms are techniques for data collection from DMs; and outcomes are the ISM outputs and MICMAC diagram. In essence there will be the following research questions that will help in addressing the second objective of this study.

- What are the different domains and sub-domains of ISM applications?

- What are the different types and numbers of variables being studied?

- What are the compositions of DMs in different studies?

- What are the different decision making and data collection techniques?

- How accurate has been the application of ISM technique, using SmartISM?

Step II: Locating Studies: As the ISM based studies are huge, only quality sources were considered, rather than an exhaustive search. As per the objectives, articles that had significant discussion and documentation on ISM application as mentioned in Step I were needed. As defined earlier, the steps of ISM are structural self-interaction matrix, initial and final reachability matrix, level partitioning, conical matrix, digraph, and final model. It was observed that an article going into the details of level partitioning had sufficient demonstration of ISM. Therefore, “Interpretive Structural Modeling” + partitioning keywords were used on ScienceDirect database and it resulted in 300 articles up to the year of 2021, of which 291 belonged to review and research articles.

Step III: Study selection and evaluation: These articles were further perused for the relevance to present study and classified into different groups such as definition only, other techniques, no partitioning, non-related, incomplete outputs, and desired study. As the articles were growing nonlinearly each year, therefore, after the year of 2017, a random selection of five articles was preferred to keep the dataset manageable. It resulted in 77 articles in the desired study group that were considered further in this study.

Step IV: Analysis and Synthesis: This step has two components: first the analysis of articles for context, interventions, and mechanisms was performed, as explained in step one, by extracting relevant information as shown in Table 2. Second was the extraction of SSIM from the 77 selected articles to reimplement the ISM technique using SmartISM. The results from the SmartISM were compared with the outcomes illustrated in the article for SSIM, RM, FRM, LP, CM, digraph, final model and edges in the final model, and MICMAC and the variations are summarized in Table 3.

Step V: Reporting and using the results: Results of analysis and synthesis are reported in results and discussion section. They have been provided in a fashion that will assist in informed-adoption and application of ISM and MICMAC, and utilization of SmartISM for academicians, practitioners, and policy makers alike.

Articles’ Details

Articles’ publication years range from 2005 to 2021. As the articles are increasing non-linearly, therefore 2017 onwards only five articles were randomly chosen for each year. The publication sources having two or more articles have been shown in Table 1. Journals in the area of sustainability have the maximum number of articles. Journal of cleaner production had published 18 articles out of 77 selected articles.

Table 1.

Publication sources for two or more articles.

4. Development of SmartISM Using Microsoft Excel

Microsoft Excel provides an excellent environment for graphical representation and modelling of virtually any conceptual framework of any discipline. It has some important features such as cellular addressable input sheets, interactive output, vector graphic objects, integral atomic access of data in multiple ways, many inbuilt data processing functions, backend VBA (Visual Basic for Applications) interface to code any logic or algorithm, mechanisms for development of event driven interfaces, ubiquitous tool and ease of use, and widespread ecosystem of support and training. Hence it makes a natural choice for practitioners, decision makers, and researchers to develop their problem-solving models in Microsoft Excel. Its applications in business statistics and decision making are widely documented. Following are some advanced applications of MS Excel in different domains such as Genetic Analysis [74], Finite Element Analysis in Engineering [75], and Pharmacokinetic Pharmacodynamic fields of Pharmacology [76]. On the flip side it has a drawback to support multiple real-time concurrent users. This section explains the functions and features of VBA to develop SmartISM, an end-to-end graphical software to automate processes of ISM and MICMAC with the help of pseudo codes. Additionally, the demonstration video for SmartISM has been attached as a Supplementary Material, see Video S1.

Firstly, the SSIM matrix defined by DMs is entered in Excel, and serves as the basic input for other steps of ISM. For n variables, the size of SSIM will be n by n. DMs will compare n(n + 1)/2 or nC2 unique pairs of variables and assign one of the relationships using symbols V, A, X, or O, as explained earlier. Thereafter, eight VBA macros will derive matrices of RM, FRM, CM, and RCM; level partitioning; and draw diagrams of digraph, final model, and MICMAC. RM is a binary form of SSIM using conversion rules for V, A, X, and O as explained earlier and keeping 1s at the diagonal positions of the matrix, as described in the following pseudo code. RM also contains the driving and dependence powers for each variable.

| Function RM |

| //copy the content of SSIM into RM |

| RM ← SSIM |

| //loops to replace V, A, X and O symbols with 1, 0, 1 and 0, digits; and putting 0,1, 1 //and 0 digits at their transposed positions; and keeping the diagonal elements as 1 |

| For i = 1 To n //n is the total number of elements |

| For j = 1 To n |

| If i = j |

| RM[i][j] ← 1 |

| If RM[i][j] = ‘V’ |

| RM[i][j] ← 1 |

| RM[j][i] ← 0 |

| If RM[i][j] = ‘A’ |

| RM[i][j] ← 0 |

| RM[j][i] ← 1 |

| If RM[i][j] = ‘X’ |

| RM[i][j] ← 1 |

| RM[j][i] ← 1 |

| If RM[i][j] = ‘O’ |

| RM[i][j] ← 0 |

| RM[j][i] ← 0 |

| //count non-zero elements in rows and columns and append to show the driving and //dependence powers |

| For i = 1 To n |

| RM[i][n + 1] ← Countif(RM[i][] != 0) |

| RM[n + 1][i] ← Countif(RM[][i] != 0) |

The second function FRM requires calculation of transitive relations among variables. For manual calculation, RM can be visualized as a digraph with variables representing nodes and 1s in the RM representing the directed edges. By tracing different paths, transitive relations can be identified. For a large number of variables the process would be tedious and leads to errors, whereas a simple Warshall algorithm [67] for transitive closure can be used to automate it. This algorithm results in generalized transitivity if applied in-place, otherwise it will give second-order or two-hop transitivity. Transitive relations are marked with 1* in FRM, see the pseudo code for main logic in the following paragraph. Moreover, the 1s and 1*s are counted in rows and columns to calculate the driving and dependence powers respectively for each variable.

| Function FRM //copy the content of RM into FRM FRM ← RM //block for generalized transitivity (all levels) Warshall algorithm in-place //start three level nested loop to parse through FRM For k = 1 To n //n is the total number of elements For i = 1 To n For j = 1 To n If FRM[i][k] = 1 And FRM[k][j] = 1 FRM[i][j] ← 1 //putting 1* to differentiate between transitive links identified and links in RM For i = 1 To n For j = 1 To n If FRM[i][j] != RM[i][j] FRM [i][j] ← *1 //block for second-order transitivity (up to second level only) Warshall algorithm //start three level nested loop to parse through FRM For k = 1 To n For i = 1 To n For j = 1 To n If RM[i][k] = 1 And RM[k][j] = 1 And FRM[i][j] = 0 FRM[i][j] ← 1* //recount non-zero elements in rows and columns and append to show the driving and //dependence powers For i = 1 To n RM[i][n + 1] ← Countif(RM[i][] != 0) RM[n + 1][i] ← Countif(RM[][i] != 0) |

The next step is to calculate the ranks of the variables through level partitioning. A new matrix LP is defined with five columns namely elements (Mi), reachability set R(Mi), antecedent set A(Mi), intersection set R(Mi)∩A(Mi) and level, and n rows. For a specific variable Mi in FRM, non-zero cells in the row comprise its reachability set and their corresponding identifiers are kept in the LP row of the same variable Mi. Similarly, non-zero cells in the column comprise its antecedent set and their corresponding identifiers are kept in the LP row of the same variable Mi. The intersection sets are calculated for all variables and variables having the same reachability and intersection sets are given first rank. In the next iteration, identifiers of all the ranked variables are removed from reachability, antecedent, and intersection sets. Again, variables having the same reachability and intersection sets are given the second rank and iteration continues until all the variables are ranked. The iteration results may be copied in one Microsoft Excel Sheet.

| Function LP //initiate a matrix LP of size n by 5 to keep element number, reachability set, antecedent //set, intersection set and levels for each of the n elements; levels will remain empty For i = 1 To n LP[i][1] ← i //reachability set R for ith element For j = 1 To n If FRM[i][j] != 0 Append jth element to R LP[i][2] ← R //antecedent set A for ith element For j = 1 To n If FRM[j][i] != 0 Append jth element to A LP[i][3] ← A LP[i][4] ← R∩A //iteration for level calculations, where levels j can go up to n For j = 1 To n //remove elements that have levels For i = 1 To n If LP[i][5] != Null For k = 1 To n Remove ith element from LP[k][2], LP[k][3], LP[k][4] //assign jth level to elements that have equal reachability and intersection sets For i = 1 To n If LP[i][2] = LP[i][4] And LP[i][5] = Null LP[i][5] ← j //print the jth iteration results Print LP |

Once the variables are ranked, a digraph can be developed easily by positioning the variables as per their ranks with the help of CM. CM is row and column wise sorted FRM as per variables’ ranks or levels. Directed edges can be drawn between variables as per non-zero cells in the CM. Two shape objects Oval and Connector are needed to automate the drawing of digraph. Positing of ovals needs to be carefully assigned, as there can be multiple ovals in one level. The simplest way to identify the needed objects in drawing is to auto record a macro and draw a sample. Afterwards, the macro can be manually edited and static names of the objects can be made dynamic for easy handling in the loop structures of VBA. The pseudo codes for the functions for CM and digraph is as follows.

| Function CM //copy the content of FRM into CM CM ← FRM //add levels from LP to CM for each element at the end of rows and columns For i = 1 To n //n is the total number of elements CM[i][n+2] ← LP[i][5] CM[n+2][i] ← LP[i][5] //Sort CM as per levels vertically and horizontally CM.Sort key1: = Range(LP[n + 2][]) CM.Sort key1: = Range(LP[][n + 2]), Orientation: = xlLeftToRight |

| Function Digraph //create ovals of size s to represent numbered nodes for each element For i = 1 To n //n is the total number of elements Ovals[i] ← Shapes.AddShape(msoShapeOval, 0, 0, s, s) Ovals[i].TextFrame.Characters.Text ← i //define and calculate the position arrays v and h of each rectangle based on //drawing canvas size, required interspacing between elements as per number of //elements, elements in each level and any offset needed Ovals[i].Top ← v[i] Ovals[i].Left ← h[i] //add directed arrows between elements based on edges in CM For i = 1 To n For j = 1 To n If CM[i][j] != 0 And i != j Shapes.Range(Ovals[i], Ovals[j]).Select Shapes.AddConnector(msoConnectorStraight, 0, 0, 0, 0).Select Selection.ShapeRange.Line.EndArrowheadStyle ← msoArrowheadOpen Selection.ShapeRange.ConnectorFormat.BeginConnect Ovals[i], 1 Selection.ShapeRange.ConnectorFormat.EndConnect Ovals[j], 5 |

The final model represents variable names in the rectangular boxes in place of their identifiers in ovals and tries to remove maximum possible transitive links from the digraph. Transitive reduction is a technique to reduce the number of transitive links. Transitive reduction is complicated, specifically for the directed cyclic graphs, and the algorithm may even distort the structure of the digraph. Therefore, an algorithm was designed to develop a reduced conical matrix (RCM) that removes maximum links without changing the structure of digraph and reachability of elements. The main logic is to remove incoming links from second lower-level variables from the CM and results in RCM, see the pseudo code for the main logic in the following paragraph. RCM was used to draw automated final ISM model using Rectangle and Connector shape objects, as in the following pseudo code.

| Function RCM //copy the content of CM into RCM RCM ← CM //start loop to parse through columns For i = 1 To n //n is the total number of elements //start loop to parse through row of specific column for lower triangular matrix For j = i To n //search for first non-zero row cell whose level is greater than the level of that //column element If (RCM[j + 1][i] = 1 Or RCM[j + 1][i] = “1*”) And RCM[j + 1][n +2] > RCM[i][n + 2] //set the L one higher than the level identified L ← RCM[j + 1] [n + 2] + 1 Break For //identify the row that has level equal to L For j = i To n If RCM[j][n + 2] = L Break For //set all the rows starting from identified row in preceding step and below up to n //as 0 For j = j To n RCM [j][i] ← 0 |

| Function FinalModel //create rectangles of size s to represent each element with variable text kept in names //array For i = 1 To n //n is the total number of elements Rects[i] ← Shapes.AddShape(msoShapeRectangle, 0, 0, s, s) Rects[i].TextFrame.Characters.Text ← names[i] //define and calculate the position arrays v and h of each rectangle based on //drawing canvas size, required interspacing between elements as per number of //elements, elements in each level and any offset needed Rects [i].Top ← v[i] Rects [i].Left ← h[i] //add directed arrows between elements based on edges in RCM For i = 1 To n For j = 1 To n If RCM[i][j] != 0 And i != j Shapes.Range(Rects [i], Rects [j]).Select Shapes.AddConnector(msoConnectorStraight, 0, 0, 0, 0).Select Selection.ShapeRange.Line.EndArrowheadStyle ← msoArrowheadOpen Selection.ShapeRange.ConnectorFormat.BeginConnect Rects [i], 1 Selection.ShapeRange.ConnectorFormat.EndConnect Rects [j], 3 |

Lastly, a macro was written to draw a MICMAC diagram. The basic input for this diagram was the dependence and driving powers of variables from FRM. This was the longest macro as it required many shape objects such as Line, Connector, Rectangle, Oval, and Textbox. However, it didn’t require any special algorithm to be used. Nevertheless, logic to initiate, aggregate, and draw different objects based on number of variables, and dependence and driving powers in a specified space, required careful arrangement.

| Function MICMAC //draw n + 1 horizontal and vertical lines where n is total number of elements spaced at //s as per canvas size and number of elements, offset has been skipped for simplification //and add numbered labels for each line For i = 1 To n + 1 Shapes.AddLine(0, i*s, n*s, i*s).Line //horizontal lines Shapes.AddLine(i*s, 0, i*s, n*s).Line //vertical lines With Shapes.AddTextbox(msoTextOrientationHorizontal, i*s, n*s, 30, 20) .TextFrame.Characters.Text ← i-1 With Shapes.AddTextbox(msoTextOrientationHorizontal, 0, i*s, 30, 20) .TextFrame.Characters.Text ← i-1 //draw middle horizontal and vertical lines that may be of higher weight With Shapes.AddLine(0, n*s/2, n*s, n*s).Line //horizontal .Weight ← 3 With Shapes.AddLine(n*s/2, 0, n*s/2, n*s).Line //vertical .Weight ← 3 //draw horizontal and vertical arrows to demarcate dependence and driving powers Shapes.AddConnector(msoConnectorStraight, 0, n*s, n*s, n*s).Select Selection.ShapeRange.Line.EndArrowheadStyle ← msoArrowheadOpen With Shapes.AddTextbox(msoTextOrientationHorizontal, n*s/2, n*s, 110, 20) .TextFrame.Characters.Text ← “Dependence Power” Shapes.AddConnector(msoConnectorStraight, 0, n*s, 0, s).Select Selection.ShapeRange.Line.EndArrowheadStyle ← msoArrowheadOpen With Shapes.AddTextbox(msoTextOrientationUpward, 0, n*s/2, 20, 80) .TextFrame.Characters.Text ← “Driving Power” //write labels for each quadrant such as autonomous (I), dependent (II), linkage (III), //and independent (IV) variables With Shapes.AddTextbox(msoTextOrientationHorizontal, 0, s*n, 130, 40) .TextFrame.Characters.Text←“I-Autonomous Variables III-Linkage Variables” With Shapes.AddTextbox(msoTextOrientationHorizontal, s*n, s*n, 135, 40) .TextFrame.Characters.Text←“II-Dependent Variables IV-Independent Variables” //place the I to IV (Roman[]) in quadrants in appropriate positions x[] and y[] For i = 1 To 4 With Shapes.AddTextbox(msoTextOrientationHorizontal, x[i], y[i], 20, 20) .TextFrame.Characters.Text ← Roman[i] //set dependence and driving in 2-dimensional arrays x and y For i = 1 To n x[i][1] ← FRM[i][n + 1] For i = 1 To n y[1][i] ← FRM[n + 1][i] //aggregate elements with same dependence and driving powers in a 2-dimensional //array E For i = 1 To n If x[1][i], y[i][1] = x[1][i], y[i][1] Append ith element at E[x[1][i]][y[i][1]] //place ovals of size o and elements on the grid, offsets have been ignored For i = 1 To nVar For j = 1 To nVar If E[i][j] != Null Shapes.AddShape(msoShapeOval, i*s, j*s, o, o) With Shapes.AddShape(msoShapeRectangle, i*s, j*s, 0, 15) .TextFrame.Characters.Text = E[i][j] |

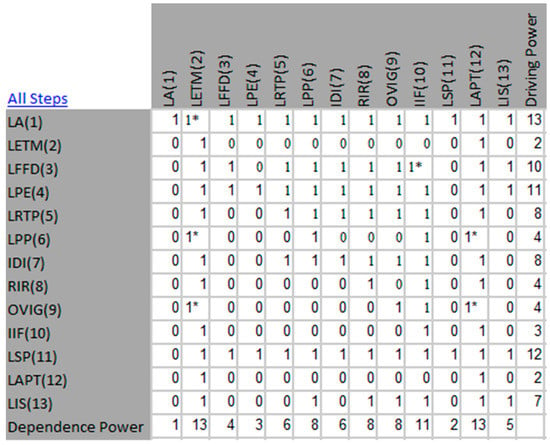

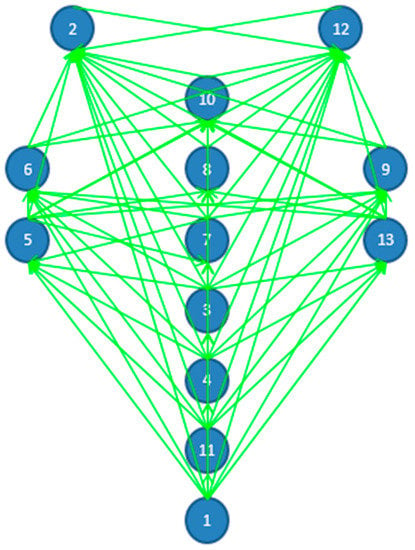

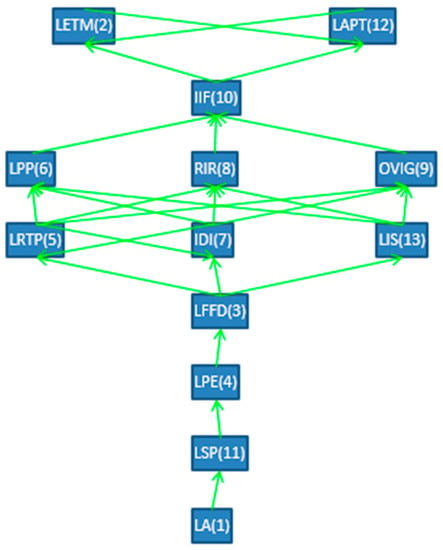

The SmartISM software was extensively tested on studies available in the literature. For any discrepancy between the reported results in the study and the SmartISM, steps were manually verified to validate the results of SmartISM, as shown in Table 3. The sample results of SmartISM for one of the previous studies [77] that had no discrepancy are shown in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 2.

Final Reachability Matrix (FRM).

Figure 3.

Digraph.

Figure 4.

Final ISM Model.

Figure 5.

MICMAC Diagram.

5. Results

This section presents the scoping review answers to the questions described in the research methodology section with respect to domain of ISM applications, variables of study, composition of decision makers, decision making, and data collection techniques, as summarized in Table 2. Furthermore, the results of the assessment of ISM technique using SmartISM on the selected 77 papers are summarized in Table 3.

Table 2.

Articles’ domain, variables, decision makers and techniques, and ISM and other MCDM approaches.

Table 3.

Assessment of application of ISM using Smart ISM.

5.1. Domain of Study

ISM is being applied in numerous fields such as sustainability, social sciences, management, engineering, and information technology. The results show 21 different domains, with highest studies in sustainability (32), supply chain and logistics (13), information technology (9), energy (5), human resource (3), marketing (3), and operations (3) (Table 2). Within sustainability, the highest studies are in the area of green supply chain management (GSCM) and sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) with seven studies each followed by two studies in construction [40,58] and several other areas such as e-waste recycling [16], healthcare waste [13], recycling 3D printing waste [47], green IT/IS [11], among others. In the area of supply chain and logistics, studies have focused on supplier relationship [9] and selection [44], food SCM [24,25], e-procurement [72], and reverse logistics [14,62,84], among others. In the field of information technology studies are conducted in the areas of building information modeling [21,93], cloud computing [37,52], e-commerce security [19], m-commerce [96], enterprise resource planning [45], supply chain management [94], and social networking sites [95]. Energy domain studies were in the area of bio-diesel [68], smart grid technologies [60], and solar energy [79]. For the human resource domain, two studies were in the area of occupational health and safety [83,89] and one in team performance [88]. The studies in the marketing area focused on motivation [39], retail brand [39], and app-based retailing [97]. Furthermore, the articles in the area of operations focused on maintenance [35,36] and lean manufacturing [12]. Some of the innovative areas were landfill communities [31], emission trading system [92], tour value [66], and quality of passenger interaction process [51].

5.2. Variables of Study

Most studies focus on enablers or drivers, challenges or barriers, critical success factors, and influencing or significant elements in the domain of research (Table 2). Other studies have tried to explore different sets of variables. For example, article [84] has studied seven attributes of third party reverse logistics; article [39] has studied 17 motivational factors in the marketing area; article [44] has used 9 corporate social responsibility factors in the area supplier selection; article [85] has studied 25 SSCM practices; article [35] interrelated maintenance tools and technique; article [11] explored 13 psychological drivers of motivation in the area of green IT/IS; article [95] studied the interrelationships between 12 factors for abandoning social networking sites; article [29] studied capabilities and drivers for new product development; and article [30] studied 13 strategies for renewable energy. The number of variables being studied ranged from 5 [58] to 32 [20]. Additionally, some studies explored two types of factors such as 10 barriers and 10 enablers [15] and 14 barriers and 15 benefits [72]. One study gave variables in two applications such as 8 CSFs for roads and bridges and 10 CSFs for embarkment [40]. These variables are identified mostly through literature review, experts’ opinions, and/or survey. Some of the unique approaches used to identify variables are thematic analysis [58], upper echelon theory [11], contingency theory [59], content analysis [52], best worst method [28], SWOT (strength, weakness, opportunity, and threat) analysis [30], idea engineering workshop [40,60], and Delphi technique [37,61].

5.3. Domain Experts or Decision Makers

This is the most crucial step as it provides the input for further steps. There are two important aspects, namely, selection of decision makers (DM) and method of information gathering from them. There are three different sets of DMs in the sample studies participants from industry, academia, and government. Participants varied from 120 through survey [64] to 2 [62,63] through group discussion and consultation. The median value of the total number of participants was 10. Only four studies [16,30,41,65] had taken participants from all three sectors: industry, academia, and government. While 56 studies had DMs from industry including others and two studies [51,72] had only academic DMs, 17 studies didn’t mention the number of DMs.

5.4. Decision Making and Data Collection Techniques

There are two approaches followed for decision making, namely, discourse and survey. For discourse many techniques have adopted such as idea engineering workshops [40,60], telephonic enquiries [43,44], group decision making [13,52], personal interview [70,78], brainstorming [16,33,34,66], laddering interview [39], direct meetings [44], semi-structured interview [21,58,93] and structured interview [69], Delphi technique [37,61], and focus group discussion [11,27]. Similarly, for surveys different techniques are as follows: individual and consensus questionnaire [43], Likert scale questionnaire [78,90], email questionnaire [44], library survey method [9], and self-administered questionnaire [46].

5.5. Assessment of Application of ISM Technique Using SmartISM

The SSIM matrices from all the 77 articles were entered into the developed SmartISM software and resulted in 77 excel files. Thereafter, for each article results were reproduced in the SmartISM software buy running the macros in 77 excel files. Variations between the reported results in the articles and corresponding SmartISM reproduced results were studied. Due to differences in transitivity incorporation FRM was checked for firstly non-incorporation of transitivity, followed by two-hop transitivity (second-order) and lastly generalized transitivity (all levels). In some cases, second order and generalized transitivity could be same. Furthermore, in case of inconsistency the digraph was manually built and transitivity was traced before reporting the results. Similarly, the complete process was analyzed to identify the reasons for the errors in any of the steps. As ISM technique is sequential, error in one step will cause subsequent steps to be erroneous specially if error exists in the steps of RM, FRM, and level partitioning.

The results of the assessments are summarized in Table 3 where ‘Y’ means the articles’ calculations match with that of SmartISM and ‘N’ means different results. For each article SSIM, RM, FRM, level partitioning, digraph, final model, edges in the final model, and MICMAC diagrams are verified. Three studies [64,92,94] didn’t report standard SSIM and two studies [15,66] had no SSIM, therefore results were not reproduced for them. Out of 72 remaining studies, 29 studies came out correct on all the parameters and their serial numbers (S. No.) are marked with stars ‘*’. Of these 29 studies, 25 had either second level (two-hop or second-order transitivity) or all levels (generalized transitivity), and four [70,71,88,97] had no transitivity calculations.

The remaining 43 studies with different results from the SmartISM outputs were further analyzed starting from first the step of SSIM and moving on until the variations were identified. One study [19] had one wrong self-relation in RM. Three studies [20,21,22] had incorrect RM and one article [93] did not provide RM and FRM. Two studies [59,89] didn’t provide RM, and their FRM didn’t match with the SmartISM output due to wrong transitivity calculations. Furthermore, eighteen studies [9,13,16,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37] had incorrect transitivity calculations leading to variations in FRM. Five studies [38,39,40,41,42] had variations at the fourth step of level partitioning. One study [31] was checked for level partitioning without transitivity as it was not considered, and came out wrong in assigning levels to variables. Finally, 12 studies had accurate hierarchical structures of variables in the final ISM model but variations in the edges that distorted the reachability of variables. Of these 12 studies, eight studies [11,14,43,44,45,46,47,48] had some extra edges and four studies [49,50,51,52] had some missing edges in the final model.

In the documentation of application of ISM, only eight studies [12,20,27,35,65,68,69,70] reported digraph. MICMAC analysis has been used by all studies except five [19,39,47,71,72] to explain grouping of the variables. Five studies [27,29,59,65,93] have explicitly mentioned X and one study [52] has mentioned 1 in the SSIM for variables to represent mutual self-relation, although it is a basic assumption in ISM therefore, other studies have not mentioned it.

6. Discussion

The operationalization of the ISM is best to be conducted through software, as there are tedious calculations such as transitivity, level partitioning, and graphical displays of digraph, final ISM model, and MICMAC diagram. Moreover, these calculations and displays need to be iterated until the high confidence model is approved by the experts. Therefore, this study has explained the methodology to develop MS Excel and VBA based, end-to-end software, SmartISM for ISM and MICMAC with the help of pseudo codes. For incorporating transitivity in FRM, the Warshall algorithm has been used, and a new algorithm RCM has been introduced for removing edges from variables’ second lower level onwards without affecting reachability and digraph structure. Further, the demonstration video of SmartISM has been added as a Supplementary Material, and this tool has been extensively tested on the existing studies and applied successfully in some of the studies [98,99,100].

Furthermore, the scoping review shows that the ISM and MICMAC techniques are being applied in different domains of social sciences, management, engineering, and technology such as sustainability, SCM, operations, manufacturing, human resource, information technology, and many other innovative areas. This technique is also employed in different multi criteria decision making techniques such as AHP, ANP, TOPSIS, DEMATEL, etc. There are four important issues that need to be addressed such as variables and their context, decision makers’ experience and numbers, decision making and data collection techniques, and utilization of software tools. The nature of variables has been enablers or drivers, challenges or barriers, critical success factors, strategies, capabilities and drivers, and influencing or significant elements in the area of study. Their numbers have varied from 5 to 32 and they have been identified through domain specific literature review, experts’ opinions, and/or survey. Furthermore, techniques such as thematic analysis, upper echelon theory, contingency theory, content analysis, best worst method, SWOT analysis, idea engineering workshop, and Delphi technique are used for variables’ identification. Similarly, the variables have been explained well to establish the contextual meaning.

Another important aspect is the experts or decision makers, as the whole analysis is dependent upon their knowledge and experience. There should be representation from all stakeholders of the domain being studied. In the best-case, experts from academia, industry, government and regulatory bodies should be selected in the panel of DMs. There are very few studies such as four in the sample of articles that have had DMs from all the stakeholders. The number of DMs varied from 2 to 120, whereas in most of the studies they were 11. Two approaches have been utilized for extracting information from DMs namely discourse and surveys. The discourse techniques are idea engineering workshops, telephonic enquiries, group decision making, personal interview, brainstorming, laddering interview, direct meetings, semi-structured and structured interview, Delphi technique, and focus group discussion. Survey techniques have used individual and consensus questionnaires, Likert scale questionnaire, email questionnaire, library survey method, and self-administered questionnaire.

The SmartISM reproduced results, on the existing studies selected in scoping review, show that only 29 out of 77 studies had correct calculations with varied transitivity incorporation such as no transitivity, second order transitivity, or generalized transitivity. Wrong transitivity calculation has been the most frequent reason for incorrect ISM results followed by variations in drawing edges in the final model that affects the reachability of the variables.

Lastly, five studies didn’t report standard SSIM, which is essential to reproduce the calculations. Therefore, as a standard practice some minimum outputs must be reported namely SSIM, FRM, level partitioning (final after all iterations), and final ISM model. Similarly, MICMAC analysis is also an important and indispensable part of ISM, as all studies except five have used it for classifying variables into one of the four groups, namely, dependent, independent, linkage, and autonomous.

7. Conclusions

Human decisions play a very important role in any social or technical system development. Domain experts have intricate knowledge on the system and can predict the contextual interrelationships between the variables of interest in the particular domain. The interpretive structural modelling technique can assemble their tacit knowledge into a tangible hierarchical model leading to an enhanced understanding of the subject. This study has developed a software tool such as SmartISM to implement ISM in an error-free, user-friendly, and graphical style. In addition to automation of existing routines of ISM, the Warshall algorithm is used for transitivity calculations and a new algorithm, reduced conical matrix, has been introduced to convert the digraph into a final model with lesser edges while retaining the digraph structure and reachability of variables. Furthermore, the scoping review of this research will guide practitioners, policy makers, and academicians in applying this technique in different disciplines in an informed way. It will help in managing ISM configuration settings such as variables’ selection, composition of decision makers, decision making, and data collection techniques. The poor results of assessment of application of ISM technique in the previous studies necessitate the utilization of an end-to-end software, such as SmartISM, to produce a high confidence final model, explaining the interrelationships between important constructs in the applied domain. To limit the number of articles in the review process only the ScienceDirect database was used, and for the last four years articles were randomly selected; therefore, results should be interpreted accordingly. The future studies will focus on the development of software tools to apply ISM in conjunction with other MCDM techniques such as AHP, ANP, TOPSIS, and DEMATEL.

Supplementary Materials

The following is available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su13168801/s1, Video S1: The SmartISM software demonstration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.A. and A.Q.; methodology, N.A.; software, N.A.; validation, N.A. and A.Q.; formal analysis, N.A.; investigation, A.Q.; resources, A.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, N.A.; writing—review and editing, N.A. and A.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Authors are highly thankful to the King Khalid University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia for all the support provided for this research work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Warfield, J.N. An Assault on Complexity; Office of Corporate Communications: Battelle, FI, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Warfield, J.N. Developing subsystem matrices in structural modeling. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1974, 4, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warfield, J.N. Developing interconnection matrices in structural modeling. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1974, 4, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warfield, J.N. Societal Systems: Planning, Policy and Complexity; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. 25 Years Ago I Coined the Phrase “Triple Bottom Line.” Here’s Why it’s Time to Rethink it. Harvard Business Review. 25 June 2018. Available online: https://hbr.org/2018/06/25-years-ago-i-coined-the-phrase-triple-bottom-line-heres-why-im-giving-up-on-it (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- Farris, D.R.; Sage, A.P. On the use of interpretive structural modeling for worth assessment. Comput. Electr. Eng. 1975, 2, 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warfield, J.N. Structuring Complex Systems, (A Battelle Monograph No. 4); Battelle Meml. Inst: Columbus, OH, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Godet, M. Introduction to la prospective: Seven key ideas and one scenario method. Futures 1986, 18, 134–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beikkhakhian, Y.; Javanmardi, M.; Karbasian, M.; Khayambashi, B. The application of ISM model in evaluating agile suppliers selection criteria and ranking suppliers using fuzzy TOPSIS-AHP methods. Expert Syst. Appl. 2015, 42, 6224–6236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Madan Shankar, K.; Kannan, D. Application of fuzzy analytic network process for barrier evaluation in automotive parts remanufacturing towards cleaner production—A study in an Indian scenario. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalvi-Esfahani, M.; Ramayah, T.; Nilashi, M. Modelling upper echelons’ behavioural drivers of Green IT/IS adoption using an integrated Interpretive Structural Modelling—Analytic Network Process approach. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 583–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.P.; Wong, K.Y. Synergizing an ecosphere of lean for sustainable operations. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 85, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Singh, A. A hybrid multi-criteria decision making method approach for selecting a sustainable location of healthcare waste disposal facility. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 139, 1001–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, G.; Pokharel, S.; Kumar, P.S. A hybrid approach using ISM and fuzzy TOPSIS for the selection of reverse logistics provider. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2009, 54, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanot, N.; Rao, P.V.; Deshmukh, S.G. An integrated approach for analysing the enablers and barriers of sustainable manufacturing. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 4412–4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Dixit, G. An analysis of barriers affecting the implementation of e-waste management practices in India: A novel ISM-DEMATEL approach. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 14, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Quadri, N.; Qureshi, M.; Alam, M. Relationship Modeling of Critical Success Factors for Enhancing Sustainability and Performance in E-Learning. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, Q.N.; Qureshi, M.R.N.; Alsayed, A.O.; Ahmad, N.; Sanober, S.; Shah, A. Assimilating E-Learning barriers using an interpretive structural modeling (ISM). In Proceedings of the 2017 4th IEEE International Conference on Engineering Technologies and Applied Sciences (ICETAS), Salmabad, Bahrain, 29 November–1 December 2017; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, F.T.C.; Guo, Z.; Cahalane, M.; Cheng, D. Developing business analytic capabilities for combating e-commerce identity fraud: A study of Trustev’s digital verification solution. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 878–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, R.D.; Narkhede, B.; Gardas, B.B. To identify the critical success factors of sustainable supply chain management practices in the context of oil and gas industries: ISM approach. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 68, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.; Chen, K.; Xue, F.; Lu, W. Barriers to Building Information Modeling (BIM) implementation in China’s prefabricated construction: An interpretive structural modeling (ISM) approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 219, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardas, B.B.; Raut, R.D.; Narkhede, B. Determinants of sustainable supply chain management: A case study from the oil and gas supply chain. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 17, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandramowli, S.; Transue, M.; Felder, F.A. Analysis of barriers to development in landfill communities using interpretive structural modeling. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokarn, S.; Kuthambalayan, T.S. Analysis of challenges inhibiting the reduction of waste in food supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 168, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayant, A.; Azhar, M. Analysis of the Barriers for Implementing Green Supply Chain Management (GSCM) Practices: An Interpretive Structural Modeling (ISM) Approach. Procedia Eng. 2014, 97, 2157–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Rahman, Z. Brand experience anatomy in retailing: An interpretive structural modeling approach. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 24, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patidar, L.; Soni, V.K.; Kumar Soni, P. Development of a Framework for Implementation of Maintenance Tools and Techniques Using Interpretive Structural Modeling. Mater. Today Proc. 2017, 4, 8158–8166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.P.; Kodali, R.B.; Gupta, G.; Mundra, N. Development of a Framework for Implementation of World-class Maintenance Systems Using Interpretive Structural Modeling Approach. Procedia CIRP 2015, 26, 424–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Raut, R.D.; Gardas, B.B.; Jha, M.K.; Priyadarshinee, P. Examining the critical success factors of cloud computing adoption in the MSMEs by using ISM model. J. High Technol. Manag. Res. 2017, 28, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A.; Shankar, R.; Tiwari, M.K. Modeling agility of supply chain. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardas, B.B.; Raut, R.D.; Narkhede, B. Modeling causal factors of post-harvesting losses in vegetable and fruit supply chain: An Indian perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 80, 1355–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, M.; Arshinder, K. Modeling the causes of food wastage in Indian perishable food supply chain. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 114, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaswan, M.S.; Rathi, R. Analysis and modeling the enablers of Green Lean Six Sigma implementation using Interpretive Structural Modeling. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 1182–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.M.; Hossen, M.A.; Mahtab, Z.; Kabir, G.; Paul, S.K.; ul Haq Adnan, Z. Barriers to lean six sigma implementation in the supply chain: An ISM model. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 149, 106843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarei, P.K.; Chand, P.; Gupta, H. Barriers to the adoption of electric vehicles: Evidence from India. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 291, 125847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Mota, R.; Godinho Filho, M.; Osiro, L.; Ganga, G.M.D.; de Sousa Mendes, G.H. Unveiling the relationship between drivers and capabilities for reduced time-to-market in start-ups: A multi-method approach. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 233, 108018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukeshimana, M.C.; Zhao, Z.-Y.; Nshimiyimana, J.P. Evaluating strategies for renewable energy development in Rwanda: An integrated SWOT—ISM analysis. Renew. Energy 2021, 176, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Benitez, R.; López, C.; Real, J.C. Environmental benefits of lean, green and resilient supply chain management: The case of the aerospace sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 167, 850–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L. Analyzing consumer online group buying motivations: An interpretive structural modeling approach. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Luthra, S.; Mannan, B.; Khurana, S.; Kumar, S.; Ahmad, S. Critical factors for the successful usage of fly ash in roads & bridges and embankments: Analyzing indian perspective. Resour. Policy 2016, 49, 334–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.N.; Gupta, M.P.; Ojha, A. Identifying critical infrastructure sectors and their dependencies: An Indian scenario. Int. J. Crit. Infrastruct. Prot. 2014, 7, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanji, R.; Agrawal, R. Exploring the use of corporate social responsibility in building disaster resilience through sustainable development in India: An interpretive structural modelling approach. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2020, 6, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Jugend, D.; de Sousa Jabbour, A.B.L.; Govindan, K.; Kannan, D.; Leal Filho, W. “There is no carnival without samba”: Revealing barriers hampering biodiversity-based R&D and eco-design in Brazil. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 206, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.T.; Palaniappan, M.; Kannan, D.; Shankar, K.M.; Thresh Kumar, D.; Palaniappan, M.; Kannan, D.; Shankar, K.M. Analyzing the CSR issues behind the supplier selection process using ISM approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 92, 268–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baykasoğlu, A.; Gölcük, İ. Development of a two-phase structural model for evaluating ERP critical success factors along with a case study. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2017, 106, 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, V.; Raj, T. Modelling and analysis of FMS productivity variables by ISM, SEM and GTMA approach. Front. Mech. Eng. 2014, 9, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, B.; Kiratli, N.; Semeijn, J. A barrier analysis for distributed recycling of 3D printing waste: Taking the maker movement perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241, 118313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokarn, S.; Choudhary, A. Modeling the key factors influencing the reduction of food loss and waste in fresh produce supply chains. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 294, 113063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diabat, A.; Govindan, K. An analysis of the drivers affecting the implementation of green supply chain management. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zou, P.X.W. Analysis of factors and their hierarchical relationships influencing building energy performance using interpretive structural modelling (ISM) approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 272, 122650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, S.; Bandyopadhyay, P.K. Modelling passenger interaction process (PIP) framework using ISM and MICMAC approach. J. Rail Transp. Plan. Manag. 2020, 14, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Sehrawat, R. A hybrid multi-criteria decision-making method for cloud adoption: Evidence from the healthcare sector. Technol. Soc. 2020, 61, 101258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attri, R.; Dev, N.; Sharma, V. Interpretive structural modelling (ISM) approach: An overview. Res. J. Manag. Sci. 2013, 2319, 1171. [Google Scholar]

- Attri, R. Interpretive structural modelling: A comprehensive literature review on applications. Int. J. Six Sigma Compet. Advant. 2017, 10, 258–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardas, B.B.; Raut, R.D.; Narkhede, B.E. A state-of the-art survey of interpretive structural modelling methodologies and applications. Int. J. Bus. Excell. 2017, 11, 505–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, A.; Bansal, G. Interpretive structural modelling for attributes of software quality. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2017, 14, 256–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, L.; Abbasi, A.; Ryan, M.J. Analyzing green building project risk interdependencies using Interpretive Structural Modeling. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuzeinab, A.; Arif, M.; Qadri, M.A. Barriers to MNEs green business models in the UK construction sector: An ISM analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 160, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agi, M.A.N.; Nishant, R. Understanding influential factors on implementing green supply chain management practices: An interpretive structural modelling analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 188, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, S.; Kumar, S.; Kharb, R.; Ansari, M.F.; Shimmi, S.L. Adoption of smart grid technologies: An analysis of interactions among barriers. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 33, 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewangan, D.K.; Agrawal, R.; Sharma, V. Enablers for Competitiveness of Indian Manufacturing Sector: An ISM-Fuzzy MICMAC Analysis. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 189, 416–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raci, V.; Shankar, R. Analysis of interactions among the barriers of reverse logistics. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2005, 72, 1011–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiyazhagan, K.; Govindan, K.; NoorulHaq, A.; Geng, Y. An ISM approach for the barrier analysis in implementing green supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 47, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.-L. Modeling sustainable production indicators with linguistic preferences. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 40, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muduli, K.; Govindan, K.; Barve, A.; Kannan, D.; Geng, Y. Role of behavioural factors in green supply chain management implementation in Indian mining industries. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 76, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.-Z.; Yeh, H.-R. Analysis of tour values to develop enablers using an interpretive hierarchy-based model in Taiwan. Tour. Manag. 2013, 34, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warshall, S. A theorem on boolean matrices. JACM 1962, 9, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajid, Z.; Khan, F.; Zhang, Y. Integration of interpretive structural modelling with Bayesian network for biodiesel performance analysis. Renew. Energy 2017, 107, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzon, M.; Govindan, K.; Rodriguez, C.M.T. Reducing the extraction of minerals: Reverse logistics in the machinery manufacturing industry sector in Brazil using ISM approach. Resour. Policy 2015, 46, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, H.; Rezaei, G.; Saman, M.Z.M.; Sharif, S.; Zakuan, N. State-of-the-art Green HRM System: Sustainability in the sports center in Malaysia using a multi-methods approach and opportunities for future research. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 124, 142–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, D.; Tripathy, S.; Jena, S.K.; Nayak, K.K.; Dash, A. Interpretive structural modelling (ISM) of obstacles hindering the remanufacturing practices in India. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 20, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toktaş-Palut, P.; Baylav, E.; Teoman, S.; Altunbey, M. The impact of barriers and benefits of e-procurement on its adoption decision: An empirical analysis. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2014, 158, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D. Producing a Systematic Review. SAGE Handb. Organ. Res. Methods 2009, 39, 672–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peakall, R.O.D.; Smouse, P.E. GENALEX 6: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2006, 6, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrupatla, T.R.; Belegundu, A.D.; Ramesh, T.; Ray, C. Introduction to Finite Elements in Engineering; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2002; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Huo, M.; Zhou, J.; Xie, S. PKSolver: An add-in program for pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data analysis in Microsoft Excel. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2010, 99, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, T. Analysis of interactions among the barriers to energy saving in China. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 1879–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, S.; Garg, D.; Haleem, A. An analysis of interactions among critical success factors to implement green supply chain management towards sustainability: An Indian perspective. Resour. Policy 2015, 46, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.F.; Kharb, R.K.; Luthra, S.; Shimmi, S.L.; Chatterji, S. Analysis of barriers to implement solar power installations in India using interpretive structural modeling technique. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 27, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.K.; Barve, A. Analysis of critical success factors of humanitarian supply chain: An application of Interpretive Structural Modeling. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2015, 12, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diabat, A.; Kannan, D.; Mathiyazhagan, K. Analysis of enablers for implementation of sustainable supply chain management—A textile case. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 83, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Vivek, S.; Banwet, D.K.; Shankar, R. Analysis of interactions among core, transaction and relationship-specific investments: The case of offshoring. J. Oper. Manag. 2008, 26, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagno, E.; Micheli, G.J.L.; Jacinto, C.; Masi, D. An interpretive model of occupational safety performance for Small- and Medium-sized Enterprises. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2014, 44, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Palaniappan, M.; Zhu, Q.; Kannan, D. Analysis of third party reverse logistics provider using interpretive structural modeling. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 140, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, P.; Diabat, A.; Mathiyazhagan, K. Analyzing the SSCM practices in the mining and mineral industry by ISM approach. Resour. Policy 2015, 46, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Yu, T.; Zuo, J.; Lai, X. Challenges of developing sustainable neighborhoods in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 972–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibin, K.T.; Gunasekaran, A.; Dubey, R. Explaining sustainable supply chain performance using a total interpretive structural modeling approach. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2017, 12, 104–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sağ, S.; Kaynak, R.; Sezen, B. Factors Affecting Multinational Team Performance. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 235, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaprasad, S.V.S.; Chalapathi, P.V. Factors Influencing Implementation of OHSAS 18001 in Indian Construction Organizations: Interpretive Structural Modeling Approach. Saf. Health Work 2015, 6, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luthra, S.; Haleem, A. Hurdles in Implementing Sustainable Supply Chain Management: An Analysis of Indian Automobile Sector. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 189, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sindhu, S.; Nehra, V.; Luthra, S. Identification and analysis of barriers in implementation of solar energy in Indian rural sector using integrated ISM and fuzzy MICMAC approach. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Song, X.; Wu, Y.; Liao, S.; Zhang, X. Interpretive Structural Modeling based factor analysis on the implementation of Emission Trading System in the Chinese building sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 127, 214–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, R.; Sawhney, A.; Arif, M. Prioritizing BIM Capabilities of an Organization: An Interpretive Structural Modeling Analysis. Procedia Eng. 2017, 196, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, R. Technological capabilities and supply chain resilience of firms: A relational analysis using Total Interpretive Structural Modeling (TISM). Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2017, 118, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jothimani, D.; Bhadani, A.K.; Shankar, R. Towards Understanding the Cynicism of Social Networking Sites: An Operations Management Perspective. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 189, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, N.P.; Barnard, D.J.; Baabdullah, A.M.A.; Rees, D.; Roderick, S. Exploring barriers of m-commerce adoption in SMEs in the UK: Developing a framework using ISM. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 44, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, J.; Chakrabarti, S. Insights and anatomy of brand experience in app-based retailing (eRBX): Critical play of physical evidence and enjoyment. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, Q.N.; Ahmad, N.; Qamar, S.; Khan, N.; Naim, A.; Hussain, M.R.; Qureshi, M.R.N.; Alsayed, A.O.; Mohiuddin, K. Relationship modeling for OSN-based E-Learning Deployment. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 6th International Conference on Engineering Technologies and Applied Sciences (ICETAS), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 20–21 December 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, N.; Hoda, N.; Alahmari, F. Developing a Cloud-Based Mobile Learning Adoption Model to Promote Sustainable Education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N. The Structural Modeling of Significant Factors for Sustainable Cloud Migration. Int. J. Intell. Eng. Syst. 2021, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).