Evaluating the Mental-Health Positive Impacts of Agritourism; A Case Study from South Korea

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Green Environments and Mental Health

1.2. Mental Health: Well-Being, Stress

1.3. Agritourism in Korea

1.4. Stress in South Korean Society

- Agritourism activities might contribute to improve the immediate mood and further improve mental health.

- There might be an interaction between self-reported wellbeing and agritourism.

- There might be an interaction between self-reported stress and agritourism.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

- Having easy access for visitors from Seoul city

- Being located out of the city area

- Providing both farming and leisure activities for visitors

- Providing both harvesting events and animal farms even on a small scale

- Also, we tried to select sites in different directions around the city of Seoul

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Perceived Stress

2.2.2. Wellbeing

2.2.3. Present Emotional State

2.3. Sample and Study Design

- First group: ‘Visiting agritourism sites (Agrit-group)’

- Second group: ‘Spending the weekend at home (Routine group)’

Eliminating Bias

2.4. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Measurement Results

3.2. Test of the Research Questions

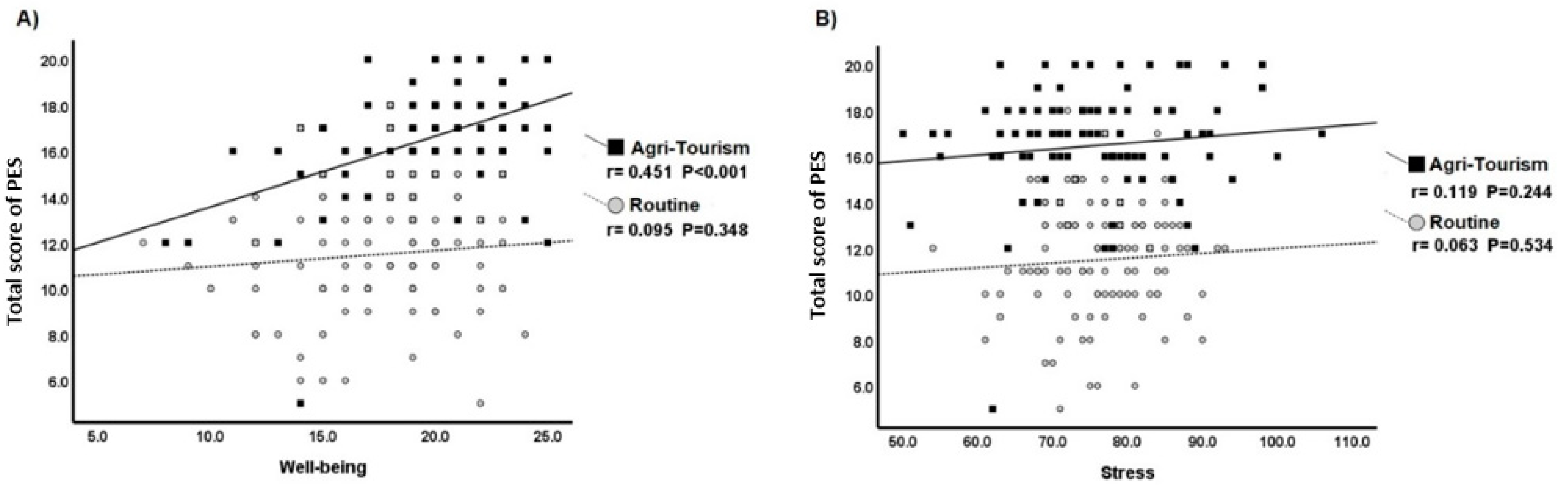

3.3. Testing the Interactions

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Practical Suggestions for Agritourism Development

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wolf, I.D.; Wohlfart, T. Walking, hiking and running in parks: A multidisciplinary assessment of health and wellbeing benefits. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 130, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedimo-Rung, A.L.; Mowen, A.J.; Cohen, D.A. The significance of parks to physical activity and public health: A conceptual model. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2005, 28, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Berg, A.E.; Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P. Green space as a buffer between stressful life events and health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P.; De Vries, S.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Green space, urbanity, and health: How strong is the relation? J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hartig, T.; Evans, G.W.; Jamner, L.D.; Davis, D.S.; Gärling, T. Tracking restoration in natural and urban field settings. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, J.; van Dillen, S.M.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P. Social contacts as a possible mechanism behind the relation between green space and health. Health Place 2009, 15, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coombes, E.; Jones, A.P.; Hillsdon, M. The relationship of physical activity and overweight to objectively measured green space accessibility and use. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Humpel, N.; Owen, N.; Leslie, E. Environmental factors associated with adults’ participation in physical activity: A review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2002, 22, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kaplan, R. Physical and psychological factors in sense of community: New urbanist Kentlands and nearby Orchard Village. Environ. Behav. 2004, 36, 313–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, S. Nearby nature and human health: Looking at mechanisms and their implications. In Innovative Approaches to Researching Landscape and Health; Routledge: England, UK, 2014; pp. 77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, J.; Aspinall, P. The restorative benefits of walking in urban and rural settings in adults with good and poor mental health. Health Place 2011, 17, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.W.; Roe, J.; Aspinall, P.; Mitchell, R.; Clow, A.; Miller, D. More green space is linked to less stress in deprived communities: Evidence from salivary cortisol patterns. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 105, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Streifeneder, T. Agriculture first: Assessing European policies and scientific typologies to define authentic agritourism and differentiate it from countryside tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 20, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinsley, R.; Lynch, P. Small tourism business networks and destination development. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2001, 20, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, C.G.; Barbieri, C.; Rich, S.R. Defining agritourism: A comparative study of stakeholders’ perceptions in Missouri and North Carolina. Tour. Manag. 2013, 37, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R.; Vass, A. Tourism, farming and diversification: An attitudinal study. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1040–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busby, G.; Rendle, S. The transition from tourism on farms to farm tourism. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciolac, R.; Adamov, T.; Iancu, T.; Popescu, G.; Lile, R.; Rujescu, C.; Marin, D. Agritourism-A Sustainable development factor for improving the ‘health’of rural settlements. Case study Apuseni mountains area. Sustainability. 2019, 11, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Flanigan, S.; Blackstock, K.; Hunter, C. Agritourism from the perspective of providers and visitors: A typology-based study. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, L.C.; Stewart, M.; Schilling, B.; Smith, B.; Walk, M. Agritourism: Toward a conceptual framework for industry analysis. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2018, 8, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frater, J.M. Farm tourism in England—Planning, funding, promotion and some lessons from Europe. Tour. Manag. 1983, 4, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojić, S. Organic Agriculture Contribution to the Rural Tourism Development in the North of Montenegro. J. Econ. Bus. 2018, 1, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dolnicar, S.; Yanamandram, V.; Cliff, K. The contribution of vacations to quality of life. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, Y.-S.; Huang, W.-S.; Yang, C.-T.; Chiang, M.-J. Work–leisure conflict and its associations with wellbeing: The roles of social support, leisure participation and job burnout. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Huang, W.-J.; Petrick, J.F. Holiday recovery experiences, tourism satisfaction and life satisfaction–Is there a relationship? Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Morimoto, K.; Nakadai, A.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Shimizu, T.; Hirata, Y.; Hirata, K.; Suzuki, H.; Miyazaki, Y.; et al. Forest bathing enhances human natural killer activity and expression of anti-cancer proteins. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2007, 20, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Morimoto, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Inagaki, H.; Katsumata, M.; Hirata, Y.; Hirata, K.; Suzuki, H.; Li, Y.; Wakayama, Y.; et al. Visiting a forest, but not a city, increases human natural killer activity and expression of anti-cancer proteins. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2008, 21, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freeman, M. From ′character-training′ to ′personal growth′: The early history of Outward bound 1941–1965. Hist. Educ. 2011, 40, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, H.K.; Jenkins, G.R. Factors associated with changes in subjective wellbeing immediately after urban park visit. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2020, 30, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L.; Hooper, P.; Foster, S.; Bull, F. Public green spaces and positive mental health—investigating the relationship between access, quantity and types of parks and mental wellbeing. Health Place 2017, 48, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrichs, M.; Baumgartner, T.; Kirschbaum, C.; Ehlert, U. Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stress. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 54, 1389–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maller, C.; Townsend, M.; St Leger, L.; Henderson-Wilson, C.; Pryor, A.; Prosser, L.; Moore, M. The Health Benefits of Contact with Nature in a Park Context: A Review of Relevant Literature; Deakin University and Parks Victoria: Melbourne, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mutz, M.; Müller, J. Mental health benefits of outdoor adventures: Results from two pilot studies. J. Adolesc. 2016, 49, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Romagosa, F.; Eagles, P.F.; Lemieux, C.J. From the inside out to the outside in: Exploring the role of parks and protected areas as providers of human health and wellbeing. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2015, 10, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P. Outdoor adventure in promoting relationships with nature. J. Outdoor Environ. Educ. 2004, 8, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greffrath, G.; Meyer, C.D.P.; Strydom, H. A comparison between centre-based and expedition-based (wilderness) adventure experiential learning regarding group effectiveness: A mixed methodology. S. Afr. J. Res. Sport Phys. Educ. Recreat. 2013, 35, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley, S.J.; Burns, V.E.; Cumming, J. The role of outdoor adventure education in facilitating groupwork in higher education. High. Educ. 2015, 69, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, E.C. Residential wilderness programs: The role of social support in influencing self-evaluations of male adolescents. Adolescence 2008, 43, 172. [Google Scholar]

- Belanger, L.; McGowan, E.; Lang, M.; Bradley, L.; Courneya, K. Adventure Therapy: A Novel Approach to Increasing Physical Activity and Physical Self-Concept in Young Adult Cancer Survivors: P3–70. Pscyho-Oncology 2013, 22, 320–321. [Google Scholar]

- Gehris, J.; Kress, J.; Swalm, R. Students’ views on physical development and physical self-concept in adventure-physical education. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2010, 29, 146–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schell, L.; Cotton, S.; Luxmoore, M. Outdoor adventure for young people with a mental illness. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2012, 6, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahn, P.; Stigsdotter, U.A. Landscape planning and stress. Urban For. Urban Green. 2003, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kondo, M.C.; Fluehr, J.M.; McKeon, T.P.; Branas, C.C. Urban green space and its impact on human health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCurdy, L.E.; Winterbottom, K.E.; Mehta, S.S.; Roberts, J.R. Using nature and outdoor activity to improve children’s health. Curr. Probl. Pediatric Adolesc. Health Care 2010, 40, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Alessandro, D.; Buffoli, M.; Capasso, L.; Fara, G.M.; Rebecchi, A.; Capolongo, S. Green areas and public health: Improving wellbeing and physical activity in the urban context. Epidemiol. Prev. 2015, 39, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- McCabe, S.; Johnson, S. The happiness factor in tourism: Subjective wellbeing and social tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 41, 42–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendelboe-Nelson, C.; Kelly, S.; Kennedy, M.; Cherrie, J.W. A scoping review mapping research on green space and associated mental health benefits. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Organisation, W.H. The World Health Report 2001: Mental Health: New Understanding, New Hope; WHO Library Cataloguing in Publication Data: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fleuret, S.; Atkinson, S. Wellbeing, health and geography: A critical review and research agenda. N. Zealand Geogr. 2007, 63, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; Lepper, H.S. A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc. Indic. Res. 1999, 46, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmack, U. The structure of subjective wellbeing. In The Science of Subjective Wellbeing; Eid, M., Larsen, R.J., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Volume 54, pp. 97–123. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, K.-S. Rural Tourism in Korea; Food & Fertilizer Technology Center: Seoul, South Korea, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Choo, H.; Jamal, T. Tourism on organic farms in South Korea: A new form of ecotourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 431–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, M.; Heo, D.S.; Jun, T.Y.; Lee, M.S.; Cho, M.J.; Han, C.; Kim, M.K. Depression, suicide, and Korean society. J. Korean Med Assoc. 2011, 54, 358–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Kim, H.J. Agricultural transition and rural tourism in Korea: Experiences of the last forty years. In Agricultural Transition in Asia; Thapa, G., Viswanathan, P., Routray, J., Ahmad, M., Eds.; Asian Institute of Technology: Bangkok, Thailand, 2010; pp. 37–64. [Google Scholar]

- Choo, H.; Park, D.B. The Role of Agritourism Farms’ Characteristics on the Performance: A Case Study of Agritourism Farms in South Korea. Int. J. Hosp. Tour. Adm. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. The “Scourge of South Korea”: Stress and Suicide in Korean Society. Berkeley Political Review. 2017, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Levenstein, S.; Prantera, C.; Varvo, V.; Scribano, M.; Berto, E.; Luzi, C.; Andreoli, A. Development of the Perceived Stress Questionnaire: A new tool for psychosomatic research. J. Psychosom. Res. 1993, 37, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fliege, H.; Rose, M.; Arck, P.; Walter, O.B.; Kocalevent, R.-D.; Weber, C.; Klapp, B.F. The Perceived Stress Questionnaire (PSQ) reconsidered: Validation and reference values from different clinical and healthy adult samples. Psychosom. Med. 2005, 67, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocalevent, R.-D.; Levenstein, S.; Fliege, H.; Schmid, G.; Hinz, A.; Brähler, E.; Klapp, B.F. Contribution to the construct validity of the perceived stress questionnaire from a population-based survey. J. Psychosom. Res. 2007, 63, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokni, L.; Park, S.-H. Measures to Control the Transmission of COVID-19 in South Korea: Searching for the Hidden Effective Factors. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2020, 32, 467–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J. Measuring Mental Health Outcomes in Built Environment Research-Choosing the Right Screening Assessment Tools; Centre for Urban Design and Mental Health: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohe, Y.; Ikei, H.; Song, C.; Miyazaki, Y. Evaluating the relaxation effects of emerging forest-therapy tourism: A multidisciplinary approach. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 322–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, J. The Tourist Gaze: Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies; Sage Publication: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, G.L.; Inglis, B.C. Adolescent leisure dimensions, psychosocial adjustment, and gender effects. J. Adolesc. 2012, 35, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grandey, A.A.; Cropanzano, R. The conservation of resources model applied to work-family conflict and strain. J. Vocat. Behav. 1999, 54, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abraham, A.; Sommerhalder, K.; Abel, T. Landscape and wellbeing: A scoping study on the health-promoting impact of outdoor environments. Int. J. Public Health 2010, 55, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coghlan, A. Tourism and health: Using positive psychology principles to maximise participants’ wellbeing outcomes—A design concept for charity challenge tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2015, 23, 382–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhakka, R.; Pitkänen, K.; Siikamäki, P. The health and well-being impacts of protected areas in Finland. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1830–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Factors | Total | Routine (n = 100) | Agrit (n = 100) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <20 | 36 (18%) | 17 (17%) | 19 (19%) | 0.022 |

| 21–30 | 42 (21%) | 18 (18%) | 24 (24%) | ||

| 31–40 | 57 (28.5%) | 31 (31%) | 26 (26%) | ||

| 41–50 | 37 (18.5%) | 15 (15%) | 22 (22%) | ||

| 51–60 | 22 (11%) | 14 (14%) | 8 (8%) | ||

| 61–70 | 4 (2%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | ||

| >71 | 2 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Gender | Female | 98 (49%) | 51 (51%) | 47 (47%) | 0.673 |

| Male | 102 (51%) | 49 (49%) | 53 (53%) | ||

| WB | 18.50 ± 3.53 | 17.54 ± 3.37 | 19.45 ± 3.44 | <0.001 | |

| ST | 76.23 ± 9.18 | 76.40 ± 7.41 | 76.06 ± 10.75 | 0.681 | |

| PES 1 | 3.54 ± 1.04 | 2.98 ± 1.03 | 4.10 ± 0.67 | <0.001 | |

| PES 2 | 3.50 ± 1.12 | 2.86 ± 1.05 | 4.13 ± 0.76 | <0.001 | |

| PES 3 | 3.33 ± 1.23 | 2.52 ± 1.06 | 4.14 ± 0.78 | <0.001 | |

| PES 4 | 3.62 ± 0.93 | 3.13 ± 0.86 | 4.11 ± 0.72 | <0.001 | |

| Total PES | 13.98 ± 3.47 | 11.49 ± 2.48 | 16.48 ± 2.35 | <0.001 | |

| Multivariate Analysis | Univariate Analysis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PES 1 | PES 2 | PES 3 | PES 4 | |||||||

| Effect | Pillai’s Trace | p | η2 | p | η2 | p | η2 | p | η2 | p |

| Group * | 0.496 | <0.001 | 0.261 | <0.001 | 0.306 | <0.001 | 0.397 | <0.001 | 0.252 | <0.001 |

| Gender | 0.018 | 0.511 | 0.003 | 0.491 | <0.001 | 0.924 | 0.001 | 0.677 | 0.009 | 0.185 |

| Age | 0.192 | 0.116 | 0.029 | 0.597 | 0.076 | 0.037 | 0.06 | 0.115 | 0.035 | 0.467 |

| WB | 0.078 | 0.005 | 0.028 | 0.022 | 0.041 | 0.005 | 0.057 | 0.001 | 0.015 | 0.092 |

| ST | 0.038 | 0.131 | 0.002 | 0.581 | 0.028 | 0.022 | 0.006 | 0.293 | 0.007 | 0.261 |

| PES 1 | PES 2 | PES 3 | PES 4 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (95% CI) | p Value | B (95% CI) | p Value | B (95% CI) | p Value | B (95% CI) | p Value | ||

| Agrit-group | 1.076 (0.813, 1.339) | <0.001 | 1.229 (0.96, 1.497) | <0.001 | 1.519 (1.247, 1.79) | <0.001 | 0.955 (0.716, 1.194) | <0.001 | |

| Gender | Male | 0.089 (−0.165, 0.342) | 0.491 | −0.013 (−0.271, 0.246) | 0.924 | 0.055 (−0.206, 0.317) | 0.677 | −0.155 (−0.385, 0.075) | 0.185 |

| Age | <20 | −0.253 (−1.01, 0.504) | 0.51 | 0.031 (−0.742, 0.803) | 0.938 | −0.506 (−1.286, 0.274) | 0.202 | −0.149 (−0.836, 0.539) | 0.67 |

| 21–30 | −0.327 (−1.05, 0.395) | 0.372 | 0.073 (−0.665, 0.81) | 0.846 | −0.544 (−1.289, 0.201) | 0.151 | 0.008 (−0.648, 0.665) | 0.98 | |

| 31–40 | −0.112 (−0.828, 0.604) | 0.758 | 0.095 (−0.636, 0.826) | 0.798 | −0.171 (−0.909, 0.567) | 0.648 | 0.23 (−0.42, 0.88) | 0.486 | |

| 41–50 | −0.184 (−0.911, 0.543) | 0.618 | −0.259 (−1.001, 0.483) | 0.491 | −0.415 (−1.165, 0.334) | 0.276 | 0.093 (−0.568, 0.753) | 0.782 | |

| 51–60 | −0.118 (−0.91, 0.673) | 0.769 | 0.658 (−0.15, 1.466) | 0.11 | −0.405 (−1.222, 0.411) | 0.329 | 0.15 (−0.569, 0.869) | 0.682 | |

| 61–70 | 0.054 (−1.051, 1.16) | 0.923 | 0.38 (−0.748, 1.509) | 0.507 | 0.703 (−0.437, 1.843) | 0.225 | 0.503 (−0.501, 1.508) | 0.324 | |

| >71 | 0.915 (−0.501, 2.33) | 0.204 | −0.638 (−2.083, 0.807) | 0.385 | −0.244 (−1.703, 1.216) | 0.742 | 0.541 (−0.744, 1.827) | 0.407 | |

| WB | 0.043 (0.006, 0.079) | 0.022 | 0.053 (0.016, 0.091) | 0.005 | 0.064 (0.026, 0.102) | 0.001 | 0.029 (−0.005, 0.062) | 0.092 | |

| ST | −0.004 (−0.018, 0.01) | 0.581 | 0.017 (0.002, 0.031) | 0.022 | 0.008 (−0.007, 0.022) | 0.293 | 0.007 (−0.005, 0.02) | 0.261 | |

| R2 | 0.34 | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.32 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.30 | 0.36 | 0.47 | 0.28 | |||||

| Parameter | B (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | −0.024 (−0.676, 0.628) | 0.943 |

| age | <20 | −0.877 (−2.824, 1.07) | 0.377 |

| 21–30 | −0.791 (−2.65, 1.069) | 0.405 | |

| 31–40 | 0.042 (−1.8, 1.884) | 0.964 | |

| 41–50 | −0.766 (−2.636, 1.104) | 0.422 | |

| 51–60 | 0.285 (−1.752, 2.322) | 0.784 | |

| 61–70 | 1.641 (−1.204, 4.486) | 0.258 | |

| >71 | 0.574 (−3.068, 4.217) | 0.757 | |

| Agrit-group | 4.779 (4.102, 5.456) | <0.001 | |

| WB | 0.189 (0.094, 0.283) | <0.001 | |

| ST | 0.028 (−0.008, 0.063) | 0.130 | |

| R2 | 0.57 | ||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.55 | ||

| Dependent Variable: PES | ||

|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Beta (95% CI) | p Value |

| Intercept | 10.267 (7.850, 12.685) | 0.000 |

| Agrit-group * | 0.208 (−3.359, 3.776) | 0.908 |

| Wellbeing | 0.070 (−0.066, 0.205) | 0.311 |

| Interaction of Agrit-group * and wellbeing | 0.239 (0.049, 0.429) | 0.014 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rezaei, M.; Kim, D.; Alizadeh, A.; Rokni, L. Evaluating the Mental-Health Positive Impacts of Agritourism; A Case Study from South Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8712. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168712

Rezaei M, Kim D, Alizadeh A, Rokni L. Evaluating the Mental-Health Positive Impacts of Agritourism; A Case Study from South Korea. Sustainability. 2021; 13(16):8712. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168712

Chicago/Turabian StyleRezaei, Mehdi, Doohwan Kim, Ahad Alizadeh, and Ladan Rokni. 2021. "Evaluating the Mental-Health Positive Impacts of Agritourism; A Case Study from South Korea" Sustainability 13, no. 16: 8712. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168712

APA StyleRezaei, M., Kim, D., Alizadeh, A., & Rokni, L. (2021). Evaluating the Mental-Health Positive Impacts of Agritourism; A Case Study from South Korea. Sustainability, 13(16), 8712. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13168712