1. Introduction

Just Sustainability refers to a wider perspective of environmental education that combines ecological principles with social justice principles [

1,

2,

3]. Increasing literacy in ecological, economic, and social sustainability is emerging in society and academia. Discourse around the concept of “Just Sustainability” is emerging in transnational community groups. This suggests the need for a parallel dialogue within the community of early childhood education [

4]. Early childhood environmental education must include opportunities for concrete actions in favor of the environment, as well as opportunities for learning to be respectful of differences and developing an identity as world citizens [

5,

6]. Davis and Elliott [

7] urge researchers and practitioners to recognize the competences of young children as “thinkers, problem-solvers, and agents of change for sustainability” (p. 1). The concept of “Just Sustainability” originates from the field of environmental justice and is “a framework for integrating class, race, gender, environment and social justice concerns” [

1] (p. 753). Shared storytelling with personal dolls is a powerful tool for anti-bias education and is a strategy to engage children as agents of change and ecological sustainability advocates through the identities of personal dolls for themselves and peers in the classroom community [

8,

9,

10]. Boldermo and Ødegaard [

5] draw from their research an understanding of “education for sustainability as a process of social and cultural learning and, fundamentally, a value-based approach for developing new understandings and practices that give better conditions for all children” (p.458). The authors propose, “By sustaining equity, future generations’ ability to live together in diverse societies will be nourished” (p. 458).

This inquiry is a three-fold documentation of autohistoria-teorías/autobiographical theories [

11] collected in the laboratory as a narrative inquirer and carried into the field as a lead teacher. The three-folds are as follows: (1) the social construction of the persona doll named “Logan” generated from a study conducted to gather experiences of REMIDA Reggio-inspired educators’ approaches to identity studies with reuse materials, (2) a (dis)rupture that took place in my preschool classroom when I engaged the persona doll Logan to introduce the term “transgender” during circle time, which resulted in a classroom family disenrolling from the program, and (3) lessons gained from the experience to reimagine early childhood education for social sustainability. Bodermo and Ødegaard [

5] cite a 2011 report “Taking children seriously—how the EU can invest in early childhood education for a sustainable future” [

12] as findings that support how “even very young children are capable of advanced thinking in the context of social and environmental issues” [

12] (p. 459). The integration of social and environmental equity seeks to avoid unequal policies and to encourage inclusive public involvement in the production of space. Eizenberg and Jabereen [

13] point to Frazer [

14] who contends that “intersubjectivity” must be realized, which “requires that institutionalized cultural patterns of interpretation and evaluation express equal respect for all participants and ensure equal opportunity for achieving social esteem. This precludes cultural patterns that systematically depreciate some categories of people and the qualities associated with them” (p. 31). Social sustainability defends politics of recognition, which include policies aiming “to revalue unjustly devalued identities”, such as queer politics, critical “race” politics, and deconstructive feminism, which reject the “essentialism” of traditional identity politics [

13]. This paper focuses on engaging reuse persona dolls in early childhood education for Just Sustainability with an emphasis on gender justice.

What follows are definitions for two terms central to this study—REMIDA and Reggio-inspired. Reggio Emilia philosophy refers to the relationship and community-based education developed by a set of schools in Reggio Emilia, Italy. The philosophy has evolved since its inception in the late 1940s. Educators in Reggio Emilia, including co-founder Loris Malaguzzi, have been inspired by early childhood psychologists and philosophers such as Dewey, Piaget, Vygotsky, Gardner, and Bruner [

15].

The name REMIDA (harkening the name King Midas) refers to a creative recycling center for reclaiming goods. The original REMIDA location is geographically located in the city of Reggio Emilia, located in northern Italy in the province of Emilia-Romagna. However, there are now 17 REMIDA centers worldwide, located in places such as Denmark, Germany, and Australia. The idea of REMIDA can be considered an alternative educational viewpoint and is a conceptual, educational, and environmental space to learn about repurposing material goods for educational [

16].

Unlike traditional persona dolls engaged in anti-bias education who are socially constructed as another child in the classroom, “Logan” is made out of reuse materials and embodies the characteristics of a teacher. Logan’s persona represents a student teacher, and the focus group ascribed a gender non-binary identity and gender-neutral pronouns to the doll.

As a cultural artifact, Logan illuminates that from the perspective of the participant educators, preprimary age children are competent and capable of socially constructing complex knowledge and representing their theories on identity and ecology with salvaged materials. As the coordinator of a REMIDA-inspired center, I have traveled to several schools, introducing the doll to classrooms of children and opening the community to their ways of living and experiencing the world around many topics involving ecology, culture, and learning. This inquiry brings forward the story of Logan, whose life was born out of a narrative inquiry focus group.

Anzaldúa [

17] describes autohistoria-teoría in multiple ways including “as a personal essay that theorizes” (p. 578). Pitts [

18] extracts that “from this brief articulation, Anzaldúa appears to point to the manner in which the act of giving meaning to oneself provides a platform for collaborative forms of meaning-making” (p. 2). Keating (2008) has noted that although Anzaldúa never offered a systematic definition of the concept of autohistoria-teoría, she did exercise the theory throughout her writings, interviews, lectures, and teaching (as cited in [

18]).

As a Chicana REMIDA Reggio-inspired teacher/educator, and in keeping with a prominent Chicana approach to social science research, I think with Anzaldúa’s [

11] autohistoria-teoría/autobiographical theory. Thinking with theories is a posthumanist assumption that theory is method [

19]. I assume that theory is method [

20] as thinking with theory and advocate for research to be a process of assembling data and theory together. Autohistoria theory signifies a transformation of traditional Western autobiographical forms through reflective self-awareness in the service of social justice work. Autohistoria focuses on the personal life story but, as the autohistorian tells their own story, they simultaneously tell the life stories of others [

21].

2. Literature Review

Gender is learned; it is a social construct. There is a lack of literature connecting children’s social identity formation and education for ecological sustainability in early childhood education. This gap in literature can be attributed to a common misconception that young children are not able to understand and express more complex social identity nor identify with ecological and sustainable education principles [

8,

22,

23]. However, this inquiry illuminates that from the perspective of Reggio-inspired educators’ social constructivist experiences, preprimary age children are in fact competent and capable of socially constructing complex knowledge [

15,

24] and of representing their theories on identity and ecology through reuse materials [

8,

16,

25,

26].

Developmental psychology is the scientific study of the changes that occur in human beings over the course of their lives. Previous findings in the field show that until the age of 8, young children’s conceptions of social identities focus largely on behavioral and dispositional properties as opposed to belief-based aspects of identity [

22,

27,

28]. There is a paucity of literature focused specifically on how children construct social identities. In fact, existing research has either focused primarily on the formation of children’s individual identities [

22,

27,

28] or has not differentiated between children’s personal and social identities [

29]. Traditionally, the construct of a child’s ecological self has been largely neglected, and this omission may be, in part, because some researchers believe that social identity constructions are too complex for preoperational cognition [

22,

27,

28].

However, emerging discourses in early childhood identity theory trend toward the multiplicity of social identities [

15,

30,

31,

32]. A crisscrossing of identities has been used to define the intersectionality of race, gender, sexuality, and class identifications. Multiplicity of identities references the entirety of this definition of intersectionality [

33,

34]. A consequential aim of this inquiry is to narrow the gap in research on ecological identity construction [

35].

2.1. REMIDA Creative Reuse Cultural Education

An alternative educational viewpoint offered through the research in the Municipal Infant-Toddler Centers and Preprimary Schools of Reggio Emilia, Italy comes through an ongoing cultural project in their REMIDA creative recycling center that had been explicitly ascribing high value to the use of waste materials as a part of young children’s educational experiences since 1996 [

36]. The optimistic underlying point of view on reversing environmental degradation through REMIDA pedagogy provides children with opportunities to co-construct complex social identities in Reggio’s Municipal Infant/Toddler Centers and Preprimary Schools. The approach involves actively engaging children and educators in hands-on experiences that approach ideas related to environmental and social sustainability work with reuse materials. REMIDA represents a theory that draws from (yet goes beyond) the geographic terrain from which it originates. This theory encompasses an ecological and socially sustainable mindset as well.

2.2. Persona Dolls

Whitney’s [

10] work on the power of persona dolls describes one of the most amazing anti-bias tools in the early childhood classroom. Persona dolls serve a different purpose from dramatic play dolls in a classroom. When children encounter a classroom persona doll, they are interacting with another member in the classroom. To achieve this, a persona doll is created whose identities remain as constant as those characteristics do for real children in the classroom and whose life experiences unfold just as they do for children in the classroom. These individual and social identities help the children connect with the dolls and make the dolls stories more powerful. This is unlike a dramatic play doll in the classroom whose age, name, family, identity, and gender can change any time a child in the classroom desires to do so.

Storytelling with

persona dolls (dolls that are given names, family histories, and other traits by educators) “is a powerful tool for teaching classroom and social skills, giving children words for and tools to manage their feelings, developing problem-solving and conflict resolution skills, expanding children’s comfort with difference, undoing stereotypes and biased information, and helping children to stand up against bias” [

10] (p. 233). Inviting educators to share their own stories of working with three-dimensional persona dolls constructed with reuse materials provides insights to better understand Anzaldúa’s [

11] autohistoria teoría or how they simultaneously tell the life stories of others.

2.3. Gender Identity Formation

Gender is a dimension of identity that young children are working hard to understand. It is also a topic that early childhood teachers, supervisors, and families are not always sure how to best address. Gender expression is a larger social justice issue, external influences are already at work inside the preschool classroom, impacting children’s interactions and choices for play and exploration. Without adults prompting children to consider perspectives that challenge the status quo, children, left to their own devices, tend to develop notions that conform with stereotypes (Ramsey 2004). If children are regularly exposed to images, actions, people, and words that counter stereotypes—for example through books, photographs, stories, and role models—they are likely to modify and expand on their theories [

37]. Thus, educators can offer children different perspectives, including those that counter society’s confined constructs, to allow children access to a multiplicity of roles, expressions, and identities [

38].

Gender identity in early childhood typically develops in stages. Around the age of two, children become conscious of physical differences between boys and girls. Before their third birthday, most children can easily label themselves as either a boy or a girl. By age four, most children have a stable sense of their identity. During early childhood, children learn gender role behavior; however, cross-gender preferences and play are a normal part of gender formation and exploration, regardless of their future gender identity (ies). All children construct a clearer view of themselves and their gender over time. Children who assert a gender-diverse identity know their gender as clearly and consistently as their developmentally matched peers and benefit from the same level of support, love, and social acceptance [

39].

This research is dedicated to B/border crossers and to Anzaldúa ’s [

40] conceptualization of the geographic and cultural B/borderlands—“as intensely painful yet also potentially transformational spaces where opposites converge, conflict, and transform” and to the image of the child as a global citizen who is capable of understanding and expressing more complex features of social identities. Anzaldúa [

11] describes gender bending or one whose dress or behavior does not conform to conventional gender roles as another kind of cultural “border crossing”. This author is conscientious in how psychic experience of border crossings are expressed as well as mindful of the brutality undocumented immigrants experience from trespassing the social and geographic construct of “Nation States”, considering there are estimations that by 2050, there will be 100 million climate refugees globally. Now that I have reviewed the literature, I share the materials and methods for how Logan’s persona emerged from a focus group of educators to disrupt the gender binary so rigidly acknowledged in our society.

3. Reuse Persona Dolls: Materials and Methods

This inquiry documents the story of a reuse persona doll created by a focus group conducted to gather experiences of REMIDA Reggio-inspired early childhood teacher/educators approaches to identity studies with reuse materials. I begin with a description of the setting of the study in a REMIDA-inspired creative reuse center, which is followed by participant recruitment and a presentation of the data collection procedures used to conduct the activity-oriented focus group [

41].

3.1. REMIDA-Inspired Setting of the Study

The setting of the study was an early childhood development center (CDC) situated within a public university found in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States (U.S.). I have given it the pseudonym “laboratory CDC” to protect the confidentiality of the school and participants. This laboratory child development center is strongly influenced by the philosophies of the Municipal Preprimary Schools and Infant/Toddler Centers of Reggio Emilia, Italy. The specific location where the focus group discussions were held was in the Inventing REMIDA identity atelier located on the third floor of the center. This emerging creative reuse cultural project is developing into a center filled with creative, intelligent reuse [

42] materials that are available to the larger early childhood community. This Inventing REMIDA project involves graduate students enrolled in the early childhood master’s degree program, the laboratory CDC faculty and staff, and the community in undertaking a cultural project with the aims of reclaiming and repurposing industrial discards and educating community members (especially early childhood teachers) on how to reuse these valuable materials in the classroom, school, and community projects [

16].

There, I collected and interpreted focus group discussions from educators who identify as social constructivists and are involved in identity studies and creative reuse research with children 2 to 5 years of age. I introduced the question prompts and restated the purpose of the discussion, and I came and went from the room, but with the participant’s permission, I left a recorder and was also listening in on the conversation. I worked with three pairs of educators from two child development centers over the course of the study, and a group of five of the educators served as my final focus group. For the sake of this inquiry, I focus in particular on the laboratory CDC focus group composed of REMIDA Reggio-inspired director Joni, studio teacher Ann, and classroom teacher Clara (see

Figure 1) (pseudonyms participants chose for themselves).

3.2. Participant Recruitment

My aim was to select a range of participants with varying experiences in order to develop thick, rich descriptions of the perceptions of highly experienced educators with diverse viewpoints. Using a purposeful selection strategy, I employed the following selection criteria: (a) at least five years of experience working with children between the ages of 2 and 5 years old; (b) currently employed in a licensed, center-based CDC in a metro area that has a creative reuse cultural center (CRCC); (c) worked previously in a variety of educational settings (in-home programs, center-based, lab schools; (d) with children of varying ages within the range of 1 to 5 years, (e) identify as a social constructivist; (f) identify as ecologically minded; and (g) have varying years of mature experience teaching in the classroom. To recruit educators that identify as social constructivist and ecologically minded, I asked candidates over the phone or via email: Are you familiar with REMIDA Cultural Centers? Do you work with reuse material in the classroom? All of the participants responded positively.

3.3. Activity-Oriented Focus Group Discussion

Research related to focus group design (e.g., [

43]) has suggested that it is important to maintain a relatively tight focus and not attempt to explore too many topics during one discussion. Therefore, for my focus interview design, I chose to pose the prompt: “Create a REMIDA-inspired persona doll using reuse materials and make a story about the doll by choosing to answer the following questions about the doll”. The group was given an identity planning chart from which to select characteristics of the dolls to represent with reuse materials:

How did the persona doll come to identify as a social constructivist and REMIDA Reggio-inspired early childhood educator?

What do identity studies in early childhood education mean to the persona doll?

How has the persona doll approached identity studies with young children as a social constructivist?

Open-ended questions, brainstorming sessions, and persona dolls completed during the focus interview produced entirely new question formats for future research. For instance, in such meetings while involving hands-on exploration of materials in a focus group, this kind of immersion in the experience contributed to engaging educators’ imagination and creativity even more in a learning experience—an experience that can foster and develop ideas and new ways to organize the ecological and anti-bias learning contexts and subject matters to be offered to the children in their pedagogic experience [

44]. In such a meeting, the focus group took a multi-metaphorical approach to pedagogical notions such as how we ask children, teachers, and families to identify with reuse materials through three-dimensional social constructions of persona dolls that would personify their ideal of sustainability and reuse educational practices as an embodiment in the doll.

Just as people naturally tell stories, humans as social beings have long been gathering together and discussing important issues in groups. Focus group researchers facilitate this naturally occurring performance and have refined it to make it a method of research [

43]. One limitation of focus groups is that although participants are part of a group, the data analyses do not always consider that the opinions and ideas discussed are also

products of the group. Instead, a sequence of the individual’s contributions, rather than the part of the discussion between participants, are usually reported [

41]. To take advantage of the social dynamic inherent to the experience of being in a group, I proposed a reuse activity-oriented prompt to generate three-dimensional documentation in the form of a persona doll.

4. The Co-Construction of Logan

On the conference table, two 12-inch-tall stuffed Muslin gender-neutral craft dolls were available as well as loose parts [

45] collected and displayed from the dyadic interviews’ impermanent creative reuse prompts (see

Figure 2). These repurposed materials included leather scraps from a local family-owned business, metal recycling from a local university bike shop, and a wide variety of small “beautiful stuff”-inspired found objects [

46] collected from the laboratory CDC families. The provocation was intentionally located along a “spectrum of im/permanence” [

8]; therefore, scissors and hot glue guns were made available to fix materials together. The participants were invited to collect loose parts from the creative reuse cultural center—found objects that they could move, manipulate, control, and change while they worked. The participants could combine redesign, take apart, and put loose parts together in almost endless ways [

45].

The focus groups also had access to the multiple ateliers in the center, which were all filled with reuse materials that lend themselves to identity studies. There were organic snacks and drinking water available at a nearby table. Each small focus group was provided with a page listing a series of questions for the session.

The small focus group was given an identity planning chart to help make decisions and reach agreements about giving their persona doll a name, gender, age, race and ethnicity, favorite foods and activities, economic class, home, cultural background, spoken languages, religion or spirituality, and family structure. The group was prompted to develop stories about the doll based on a list of physical traits (see

Figure 3).

Throughout the process, participants selected reuse materials from the creative reuse center to make clothes, hair, and accessories for the dolls. In other words, the participants personified a REMIDA-inspired educator in doll creation (see

Figure 4).

Thus, using reuse materials, I asked participants to consider making persona dolls that would personify their ideal of sustainability and reuse educational practices as an embodiment in the doll. One doll named Logan chose to use gender-neutral pronouns for themselves and has a persona of gender fluidity. Another doll named Harmony in Disarray lives in a non-traditional family system where one household recycles and reuses, and the other does not. Since the focus group, these dolls have traveled to several schools, introducing themselves to classrooms of children and opening the community to their ways of living and experiencing the world around many topics, reuse materials education, gender identity, and many more.

For the sake of this paper, I have chosen to include quotes from the laboratory CDC focus group who co-constructed a reuse persona doll named Logan.

Director Joni volunteered to go first and share the cultural identities, socio-economic status, and family make-up she created with studio teacher Ann and classroom teacher Clara. Joni’s laboratory CDC group chose to start off with a ‘deeper story’ that introduces an anti-bias issue of gender fluidity: “Logan does not identify on a binary of male/female and is non-binary gender. Logan uses the pronoun they rather than he or she”. Then, Joni shared the bi-ethnic and multi-cultural family make-up her group created for the reuse persona doll, “Logan is thirty-one years old, bicultural and bilingual, and was raised by a Euro-American dad and Chinese mom. They love biking, gardening, yoga, hiking, the arts, and pizza, beer, and ice-cream”. Then, Joni shared their social construction of the doll’s socio-economic status, shared housing, and religious orientation, “Logan’s parents were middle class and Logan is currently a financially struggling, early childhood teacher living in a shared house off Hawthorne. Logan loves to travel, is single, and has housemates as well as a dog and a cat. Logan identifies as non-religious but spiritual”.

She shared how the experience was a great opportunity to talk about their collective experience of being in the laboratory CDC and what it means to come from a place of social constructivism and REMIDA-inspired work. Joni described her group’s persona doll in concrete physical terms, “Logan is tall, slim, short-haired, and has tattoos” (see

Figure 5).

The focus group was prompted—

How did the doll come to identify as a social constructivist and Reggio-inspired educator? Joni announced her group’s creation of a “new teacher—another person to join our learning community”, and she placed an immediate emphasis on the persona doll’s non-binary gender pronouns (see

Figure 6). Joni shared:

“This is Logan, intrigued by the possibility of working in a social constructivist university-based school. Logan is a funny storyteller and an extrovert working on a master’s degree in early childhood development. This first-year teacher is excited about combining an advanced degree coursework alongside working directly with children. They discover many complexities in this work—an explosion of thoughts, ideas, and exchanges among teachers, children, and families. It is exciting, overwhelming, and invigorating as well as exhausting.”

When asked, How did the doll come to identify as REMIDA-inspired?, Joni shared Logan’s philosophical approach to early childhood education: “Logan sees the value in reuse materials. Having REMIDA as a resource, inspiration, backdrop, partner, and in-house events to go to inspires Logan to incorporate the reuse and REMIDA materials in the classroom.”

She continued to share Logan’s experience of socially constructing identity studies with children as a REMIDA-inspired educator: “Logan feels a sense of professional satisfaction and of the past identity of the school as an inspiration. Logan loves the idea of ‘not knowing’, and the openness of knowing we can negotiate with children.”

After reviewing a chart of qualities to fill out for the persona doll, Joni commented to her group, “So, we have been referring to her as female”. Ann suggested that is because that their staff and the field of ECE is mostly female. Clara offered hesitantly, “Maybe she identifies as a female”? The group paused, and then Joni said, “Did you hear that legally, non-binary is now categorized as a gender? I think we should make her—their identity”. This suggestion inspired the group to give the persona doll a non-gender specific name similar to the ones they observed that student teachers at the CDC often select for themselves. They began borrowing names from student teachers in their learning community, and Joni shared how she likes a gender non-conformist name, “because it was their chosen name. This is kind of an interesting story; we have a lot of non-binary student employees who have come in and applied for a job with one name and then once they have been here, they have asked us to call them by another great chosen name”.

The group agreed that the increasing plurality of identities among the student staff was important to imbed in the reuse persona doll whom they named Logan.

The participants’ experiences of becoming REMIDA-inspired was captured in reuse collages, REMIDA-inspired documentation, and reuse persona doll creations, followed by semi-structured interview narratives. In my dissertation research, I found that inviting educators to share their own stories of socially constructed persona dolls constructed with reuse materials provides insights to better understand how they simultaneously tell the life stories of others. The reuse persona doll Logan has a storied identity that includes the identities of the research participants and simultaneously tells the life stories of gender-fluid student teachers at the lab school as well as children in the classrooms who hold non-binary gender identities. In sharing my story of engaging Logan in the classroom, I hope to tell the life stories of other educators who have experienced disrupture in early childhood education for Just Sustainability (see

Figure 7).

5. (Dis)Ruption: An Autohistoría

Although Logan inspired belonging and inclusion among the children I shared them with, one autumn, social sustainability work with the persona doll caused rupture, crisis, and disintegration in our preschool learning community. I was coordinating Inventing REMIDA, a creative reuse cultural education center housed in my campus lab school. Logan accompanied me as an artifact from my research on early childhood identity studies to schools, classrooms, workshops, and while giving tours. The children interacted with Logan during circle time and all throughout the day. Logan would introduce sustainability concepts such as reduce, reuse, recycle, and rot. Logan would invite the children to visit the REMIDA-inspired creative reuse center housed in the development center. I would also work with Logan and Harmony to introduce social stories and conversations with the children would take place around social and emotional literacies. One of our student staff chose (they, them, theirs) the same pronouns Logan had, and eventually, the children became fluent in addressing both the student staff and Logan with the correct pronouns. These interactions were supported by the teachers to build this conception of “Just Sustainabilities”. Logan is an innovative pedagogical tool and illustrates how to enrich anti-bias education with reuse materials. As a persona doll with a queer identity, Logan helps to enhance gender expression literacy and to deconstruct the gender binary-enriching education for gender justice.

However, in (dis)rupting traditional curriculums that might ignore or evade gender diversity, we experienced a tremendous rupture in our learning community. One day, I worked with Logan to introduce the concept of transgender identity during circle time. We had a student teacher in our classroom who preferred (they, them, theirs) pronouns, and I had overheard children questioning a gender non-conforming peer’s identity outside on the playground. I brought Logan, whom the children were familiar with, to circle time as a means of challenging the ways that binary thinking and language limit everyone’s expression and lived experience with gender and anatomy.

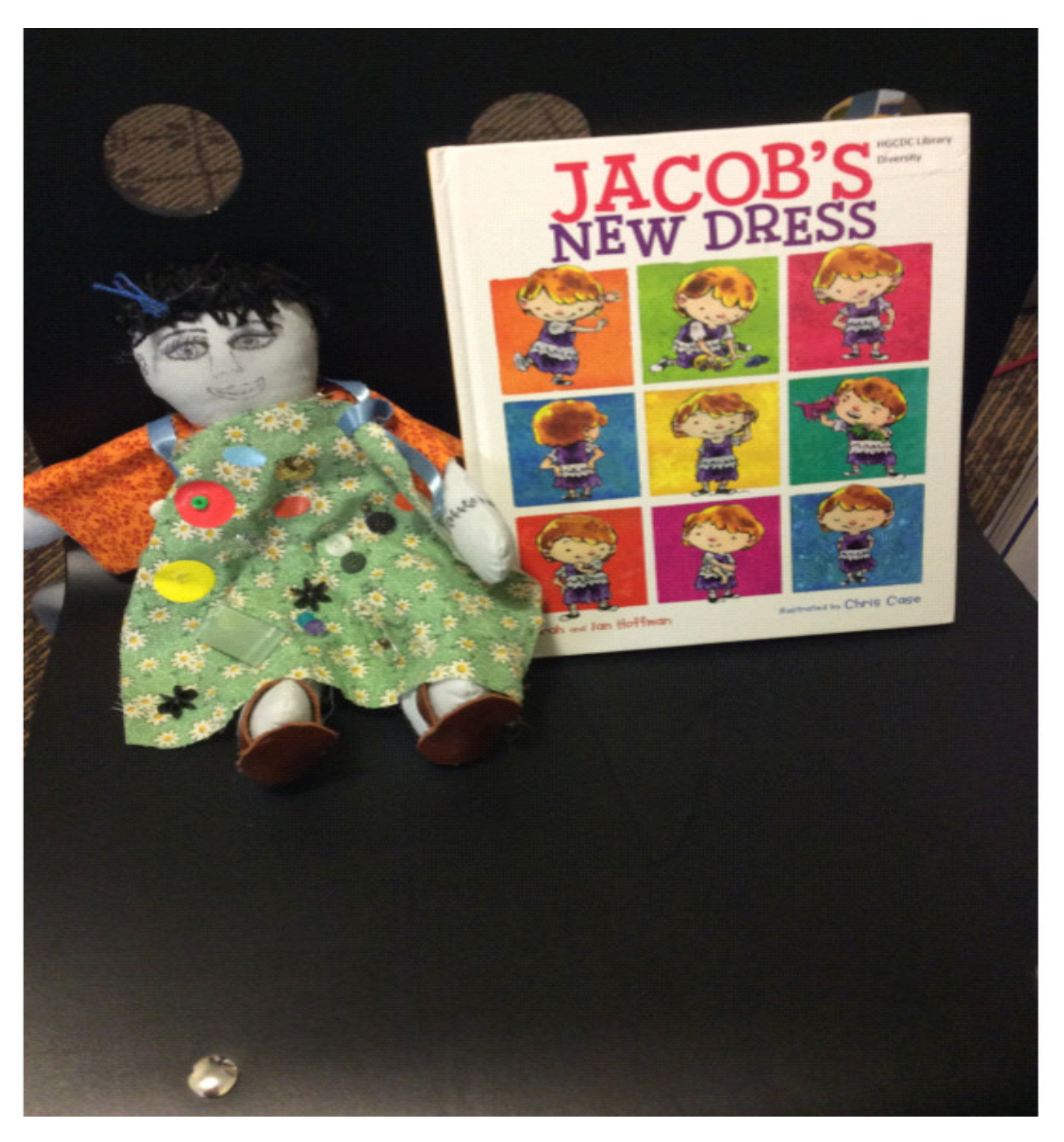

I read the story “I am Jazz” about a transgender child based on the real-life experience of Jazz Jennings who struggled with gender identity questions, which I borrowed from our extensive anti-bias library. After reading the book, Logan introduced the term “transgender” at circle time and opened up a discussion (see

Figure 8). One of our classroom families disenrolled their twin three-year-old children after we made the learning visible in a weekly newsletter. The parents felt the concept was inappropriate for a preschool classroom and were afraid I was “indoctrinating” young children. I was asked to not repeat the word transgender in the classroom again by the parents who were a same-sex couple, thus adding layers of complexity to the encounter. I was devastated by the disenrollment and worried that I would be reprimanded by my supervisors. As conversations ensued between the parents and administration, I began to doubt myself and wonder if I had in fact done something wrong. I emailed the preschool coordinator and director scholarship supporting discussing gender identity with young children and received the reply, “This article may be helpful in the future but right now our focus is on ‘damage control’. Please read the emailed draft of the parent letter I sent you this evening and add the details requested”. I was sent a draft of a parent letter my co-teacher and administration wrote, “We would like to clarify a topic that was shared in our last class news email sent to you on Friday, September 28th. In the newsletter we used the terms boy, girl, and transgender in an effort to explain to adults that the topic of gender identity and gender stereotypes had come up in conversation started by children. The term transgender was not discussed in this conversation with children.”

I was asked to sign the letter and refused. I replied, “I don’t feel comfortable writing an apologetic letter to a majority of families who haven’t complained about discussing diverse gender identities. The letter says we never actually used the word transgender when we actually did! I need to respond with integrity because I believe this incident deals directly with the heart of my dissertation work and my social justice values. I hold an image of the child as being capable and competent of processing complex social identities. I don’t feel the letter is congruent with my pedagogical stance”. I was afraid for my job and started to look for support from outside of administration. I reached out to a College of Education faculty who specializes in anti-bias curriculum and asked for pedagogical support and advocacy at a meeting that was called for with me by my supervisors.

Working with persona doll Logan had become part of my practice and part of our classroom community, and I had not thought twice about engaging them to disrupt bias through my identity studies with children. I was shocked and scared that Logan’s non-conforming gender identity had created such an eruption. As the center’s administration attempted to find a balance between advocating for both the family and our anti-bias mission statement, my co-teacher reverted to traditional activities in the classroom and distanced herself from me.

I sought out support and solidarity from teachers who were members of the anti-bias committee that had formed at our lab school. In time, this led to the creation of a “Discomfort Forum” which creates space for professional development as well as a support group for our anti-bias work. Faculty including my dissertation chair contacted the administrators and advocated for the inclusion of transgender curriculum, and the disciplinary meeting with my supervisors never took place.

Finally, we turn to lessons learned from what I call the (dis)rupture—a wordplay on (dis)card, disrupt, and the word (dis)rupture, which means a break or interruption in the normal course or continuation of some activity or process. During this disrupture in our learning community, the question of whether or not to discard Logan’s (gender non-binary) identity emerged.

6. (Be) Coming: An Autohistoria-Teoría

You overhear a familiar conversation between children on the playground when two boys pull up on tricycles and say to one of your male students who is wearing a skirt, “You are not a boy. You are a girl”. “No,” says your student, “I am a boy.” They pause and then one of them says, “Why are you wearing a girl dress”? You realize that a year after the rupture, you have another chance to engage Logan’s persona in your classroom to address gender non-conformity in a way that scaffolds the learning for children and families alike. Before engaging Logan to discuss gender justice with your classroom, you send out an introduction to families. You properly introduce your use of persona dolls including Logan, giving parents an opportunity to ask questions or make comments. This year you will start out slowly introducing complex labels and terms along a spectrum. You will begin by introducing books on gender nonconforming identities, followed by gender non-binary, and finally transgender identity expression. During the (dis)rupture one year ago, you had to hold onto your research findings, your image of the child as competent and capable of understanding and expressing complex features of social identities, your center’s anti-bias mission statement, and your commitment to gender justice in order to weather the rupture. Moving into the future, you take responsibility for making visible an anti-bias statement for your classroom, making sure you and your co-teacher are pedagogically committed to disrupt traditional curriculum, slowly scaffolding complex gender concepts for children and families, and doing ongoing self-reflection around anti-bias and antiracism, for this critical work that you are called to do.

Now that we have looked at materials and methods of doing inquiry, we turn to interpretation of findings. This chapter creates a space for the voices of early childhood educators who use alternative and reclaimed materials and is aimed at developing new knowledge—a new understanding of how educators perceive that involving children in creative experiences involving reuse materials affects the construction of their social identities (See

Figure 9).

7. Discussion

This narrative inquiry study was exploratory in nature. In fact, I only found two pieces of published research involving focus group interviews with REMIDA-inspired educations related to reusing materials with young children [

16,

47]. These studies each encompassed assemblage art and why educators deem its techniques appropriate to be incorporated in early childhood curricula following the REMIDA approach. The authors drew from focus group interviews to describe the origin and theories of the instructional approach and how creative reuse education can be taught using key ideas. A key point they made demonstrated that Reggio Emilia-inspired approaches to early childhood education are relationship-based. Therefore, interactive experiences designed to elicit REMIDA Reggio-inspired educators’ observations and reflections in a group or dyads (pairs) is complementary to the socially constructivist pedagogy they practice as co-teachers.

8. Conclusions

Defending the gender justice curriculum to administrators of the early childhood development center where I was employed, after having a family disenroll in response to transgender literacy, was a harrowing stage in my professional formation. I realized that in order to maintain personal, social, and professional integrity, I had to refuse to sign off on a letter to families denying I used the word “transgender” in my preschool classroom. I quickly searched for allies among other teachers in my school. The subsequent co-construction of a “Discomfort Forum” by the anti-bias committee teachers at the lab school emerged from this reuse persona doll rupture. We have created a new space where educators can share examples, stories, case studies, and narratives around ruptures created by anti-bias work with children and families. Anzaldúa [

11] speaks to the transformative power of new, personal, and collective stories through the metaphor of the Aztec mythical goddess of the moon, Coyolxauhqui, and as a theory to describe a complex healing process, “Coyolxauhqui personifies the wish to repair and heal, as well as rewrite the stories of loss and recovery, exile and homecoming, disinheritance and recuperation, stories that lead out of devalued into valued lives” (p.143). She adds, “Coyolxauhqui represents the search for new metaphors to tell you what you need to know, how to connect and use the information gained, and, with intelligence, imagination, and grace, solve your problems and create intercultural communities” (p.143).

As diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) increases in higher education and early childhood education in response to the 2020 protests and Black Lives Matter Movement, there is a renewed call and availability of resources for Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC), white-European, and mixed-race/heritage educators to do the work of anti-bias/antiracist culturally responsive curriculum generation. As resources, literacy, and practice increases, there will be ruptures. Autohistoria-teoría is a method for sharing experience of (dis)ruptures in the doing of early childhood education for Just Sustainability to inspire teacher/educators to persevere through finding support and community to move the work forward. Hopefully another educator who identifies as BIPOC, white European, or mixed/wPOC finds themselves in this story and is inspired to create spaces for support, resilience, and nourishing each other as teacher/educators to practice equity-based pedagogies—because we will all have moments of (dis)rupture in this work. All of this relates to being in a community as teacher activists. A community support group is necessary for professional formation, and empowers us to reconceptualize early childhood education for “Just Sustainabilities”.