Abstract

The rural collective construction land (RCCL) market imperfections, as well as informal regulations, may have contributed to high transaction costs. Well-functioning land markets play an essential role in land-use revenue, land-use efficiency, and land allocation efficiency for the rural collective economic organization (RCEO). Therefore, specific land-use patterns and detailed transaction rules for the land rental market and land sales market, respectively, make a contribution to a suitable market model with lower transaction costs and higher market efficiency. Through an empirical investigation in Nanhai District, Gungdong Province, this article builds on the theoretical framework of Williamson’s transaction costs, where the asset specificity, uncertainty, and transaction frequency have a significant influence on the RCCL market model choice. Probit model results show that (1) the RCEO prefers to choose the land sales market when the RCCL market has higher asset specificity so that the land sales market can counteract transaction costs by creating land revenue for long-term investments. Thus, the land sales market is a more appropriate choice when the trading land is a large area in a great location. (2) The rental market choice is more suitable for the RCCL market with higher transaction uncertainty. Therefore, the RCEO can detail transaction rules for the land sales and rental markets, respectively. We propose that local governments need to announce regulations for the longest contract period and the land development planning (floor area ratio, building density, floor height, etc.) of different land-use types (industrial land and commercial land) for the land sales market and the land rental market.

1. Introduction

Incomplete contract forms will cut down the investment incentives of land market players for the insufficient legal effects, which may lead to low market efficiency [1,2,3]. An incomplete contract form is mainly one without a formal written contract or legal notarization, which may bring about the incompleteness of land rights and the missing security of land rights transactions, causing these to lack legal protection. Furthermore, the land market may give rise to right disputes and social instability, extensive land use, and poor living environments. However, a well-functioning land market can promote broader rural development in many ways because it can transfer land from low-productivity producers to more productive producers and create a formal and legal trading environment, thereby increasing land productivity [4], land rights protection, and living environment improvement for sustainable rural development. To revitalize the market and improve market transaction expectations, many transition countries, including Russia, Ukraine, Czech Republic, Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria, Poland [5], and others, with the disintegration of the early 1990s, established the privatization of the land system to return the land to the original land owner, reallocate land, and cultivate the land rental market and the land sales market. The land sales market transfers full land rights to the new user and provides optimal incentives for investments by providing the permanent security of land rights [6]. Nevertheless, the land rental market provides access to land users in poor financial conditions for enabling better use of indivisible assets and creating wealth [7].

However, different land market models affect the rights and interests of transaction parties on account of institutional attributes, such as the asset specificity or uncertainty, which bring about high transaction costs [8,9]. Asset specificity means that the land function will be “limited” to a certain type, that is, the “locking effect”, for example, the characteristics of the land market trading subjects and objects and the pros and cons of the land location, which will lead to a post-monopoly advantage. For this attribute, the land sales market is a better choice to inhibit the specific investment [10,11,12,13] because a long-term investment in the land sales market can prevent losses caused by multiple transformations for specific investments. For the uncertainty attribute, asymmetric transaction information is the main risk for contract signing and performance in the land market [14], from which may emerge opportunities and “rent-seeking” and “moral risk”. The land rental market can directly improve efficiency by compensating for market failures to which tenants are subjected [15].

As one of the fastest-growing countries after the founding of the People’s Republic of China (P.R.C) in 1949, a new socialist regime gradually established a dual land ownership system within a planned economy. Under this land system, rural land is owned by the village collective, and urban land is owned by the state [16]. For state-owned land, the government holds the land rights, for rural-owned land, the rural collective holds the land rights. Land rights include land ownership, land-use rights, land income rights, and land disposal rights. Rural collective construction land (RCCL) can be transacted and used only after being expropriated as state-owned land in the process of the government’s land expropriation [17]. With the onset of industrialization over the past several decades, and with the reform and opening-up policy in 1978, the demand for construction land was accelerated in Southeastern Coastal China, especially in the Pearl River Delta Region [18]. However, the supply of state-owned construction land was insufficient and expensive [19,20,21], while there was a lot of stock rural construction land with low-efficient use in the village collective [22]. The inadequate demand for expensive urban construction land and the ample supply of cheaper rural land formed a contradiction and gradient. Therefore, the rural informal construction land market emerged in the early 1990s, and the main RCCL market model was land rental. In the land market, only the land-use rights transfer from the rural collective to the land user, while the land rights still belong to the rural collective. Most contract forms of the RCCL market were through oral agreements, without the use of standardized written contracts. These incomplete contract forms resulted in insufficient investment incentives for the demand side (enterprises) of the RCCL market due to insufficient legal effects and an uncertain transaction environment. Thus, the demand side made the choice of the land rental market, which, in turn, inhibited the exclusive use of land capital specificity in the RCCL market for the supply side (the rural collective economic organization) [3]. Moreover, the transaction happened between neighbors, kinsfolk, and members of the rural collective; thus, they were more likely to use less explicit contracts, for which trust and reputation played an important role in cooperation [23]. In 1992, the rural land shareholding system reform began, which was first tried in Nanhai District in Guangdong Province. The RCCL market transaction became more common. The form of contracts was standardized but there was a major land rental market. After 1999, a series of policies were promulgated and implemented. The RCCL market was further standardized. Then, the land rental market and the land sales market appeared. A great number of Hong Kong, Taiwanese, and foreign investors made investments and built their factories on rural land [24]. However, as discovered through the investigation of our research group, many traded rural collective construction lands are left unused due to the mismatching of the investment scale, cycle, and land area. For different demand expectations, an appropriate land model is the key to decreasing transaction specificity and uncertainty in order to reduce land transaction costs and improve the sustainability of the rural land market.

Well-functioning land market models (land rental market and land sales market) play an essential role in economic growth and development [25]. Unlike the urban land market, the detailed transaction rules of different market models have not been implemented in the RCCL market, which are established by long usage. If the rules and procedures governing use are unclear, incentives for abuse may be high [26,27]. Land market imperfections (e.g., transaction costs), as well as regulations, might have contributed and/or sustained this land-use homogenization. “Homogenization” comes with negative consequences for sustainable land use and biodiversity. In addition, credit and insurance market imperfections, as well as transaction costs due to search and contract enforcement, will affect the outcomes from land markets. The efficiency outcome might not always prevail and heavily depends on the choice of contractual arrangements [28].

Therefore, this article is to understand how transaction attributes in the RCCL market affect the functioning of land sales and rental market, which can help to design informed policies to promote sustainable land management. The research of choice of rural land rental and sales market is absent, which is important for the sustainability of rural land market development in China.

This article is organized as follows. Section 2 proposes some hypotheses in the theoretical framework of transaction costs and transaction model choice. Section 3 introduces the empirical method, including the study area, data collection, econometric model, expected impact of key explanatory variables on transaction model choice. Section 4 gives an overview of different transaction models (land rental market and land sales market) in the RCCL market. Additionally, the econometric model results will be presented and discuss in Section 4. Section 5 concludes with policy implications.

2. Theoretical Framework

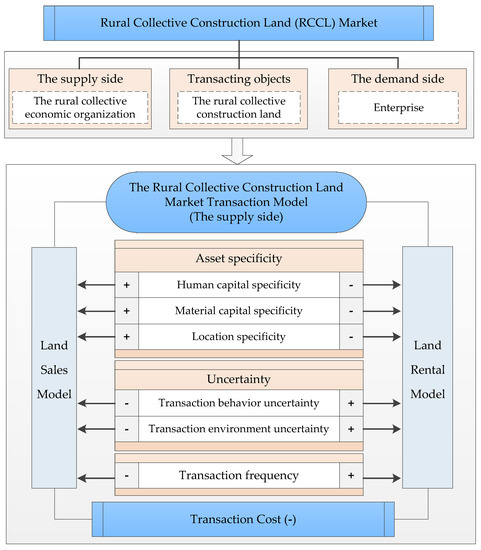

There are three factors in the RCCL market in China, the supply side, transacting objects and the demand side (Figure 1). Firstly, the supply side is the rural collective economic organization (RCEO), which is responsible for transactions of rural collective assets. The environment (price bid method, trading partner, etc.) of the RCCL market affects the transaction price, transaction method, profit expectations. Thus, the rural collective economic organization provides different transaction model options to improve transaction efficiency.

Figure 1.

The theoretical framework of Williamson’s transaction costs.

Secondly, the RCCL is the transacting object, which was converted from a large amount of farmland for the urbanization and industrialization in the past few decades. The farmland is so dispersed and fragmented spatially that the attributes (land area, land location and so on) of transacting object (RCCL) may not meet the investing requirements of the demand side, and cut down transaction efficiency [29,30]. Therefore, the supply side makes different transaction model choices to weaken specific investments of RCCL, on the other hand, improve the transaction expectations of the demanders.

Thirdly, some of the demand side (enterprises) are members of the collective economic organizations. The collective cadres may be familiar with their characteristics such as operating conditions and funding status. But some are from other cities in China, and some from other countries, which may bring about informational disadvantages for rural collective economic organizations. These institutional factors such as the specific investment, transaction environment uncertainty and information disadvantages will incur transaction costs [31,32,33]. RCEO will likely be affected by the presence of transaction costs and imperfections in the RCCL market [34].

The transaction costs idea was first proposed by Coase in “The Nature of the Enterprise” and defined as the cost of market exchange [35]. In order to conduct a market transaction, it is necessary to find out who is responsible for the transaction, tell people that they are willing to trade, negotiate, bargain, draw up a contract, and implement supervision to ensure that the terms of the contract are fulfilled. Williamson characterized economic transactions and measured transaction costs by using asset specificity, transaction frequency, and transaction uncertainty [36]. The higher the asset specificity, the greater the uncertainty, and the relatively higher the transaction frequency, the higher the transaction costs, the governance effect of land sales market will be more obvious than that of land rental market [10,31,36,37].

Firstly, asset specificity includes material specificity, human specificity, and location specificity [10,36]. The asset specificity makes interdependence between the RCEO and the enterprise at the aspect of material, human capital, and location, which is not only a type of asset specificity but also affects the transaction costs of different transaction models [38,39]. Asset specificity means that assets can easily be “locked in” a specific use, thus transaction costs will be incurred when the assets are transferred to other purposes [40]. For the RCCL market, the supply side trades the RCCL use rights with the demand side, not the land rights, which are not perpetual rights but terminable rights. Therefore, the land is easy to lock in for special use for the contract period. A land sales market can regulate market transactions and is a necessary choice for the rural collective economic organization to clarify their own profit distribution [10], which has become an important way to minimize transaction costs. The land sales market can reduce the cost of asset transfer (transaction) attached to the land.

Secondly, transaction costs include standard elements such as the effort required to obtain information on land sales and rental market participants, the negotiation of contractual terms, and contract enforcement [6], which are part of transaction uncertainty. These factors will make the RCCL sales market and rental market different. Compared to the land sales market, the land rental market is more efficient for converting land to other demanders when the transaction costs are high, and the land use right can be greatly protected in the short-term contract period.

Finally, transaction frequency is mainly manifested in two dimensions: one is the land transaction acreage. A large land transaction may bring about high transaction costs when the transaction objects negotiate and make contracts, so they refer to the land sales market for long-term use of collective construction land. Another is the operational capacity of the demand side. The demand side chooses the land sales market for long-term land-use rights, and for lower transaction costs in multiple transactions while the operational capacity is higher.

3. Empirical Method

3.1. Study Area

The RCCL market emerged in the early 1990s when RCCL transaction was forbidden by the Land Administration Law of the P.R.C (LAL; Chinese People’s Congress, 1999) of the P.R.C, which scholars called “implicit market”. There were no laws and policies of implicit RCCL market, therefore, rights security could not be protected and land rent was low. However, in fact, with accelerating urbanization and a shortage of urban land supply, the transaction of the RCCL market was still on the rise and became so prevalent that it was necessary for the government to establish and carry out counter-policies to make the RCCL market visible and legalized. The most important thing was the promulgation of measures of collective construction land-use rights transfer in addition to the experiment pilot districts, which aimed at building regulatory the RCCL market.

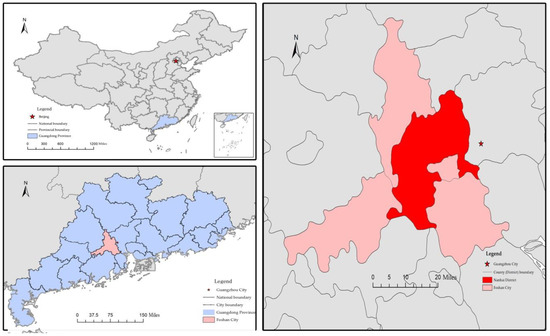

As the forefront of land system reform, Guangdong provincial government issued The Notice on Transfer of RCCL Use Rights Trial Implantation in Guangdong Province in 2003. The notice stipulated that any organization and individual could not sell or illegally transact rural collective land ownership, but could transact by assignment, transfer, lease, and mortgage. The Nanhai model started with this notice (Figure 2). Then, the Nanhai model was formalized in the draft Regulation and Administration for the Management of Collective Construction Land Use Rights Transfer in Guangdong Province in 2005, the Decree of Guangdong Provincial Government, Serial No. 100, which set up Nanhai as experimental base of the RCCL market transaction. Then the Nanhai government drafted The Assigning and Leasing Administration Measures of Collective Construction Land Use Rights in Nanhai District at Foshan City in 2011, Serial No. 308. In 2015, Nanhai District was chosen to be the state experimental pilot of RCCL system reform.

Figure 2.

Location of the study area.

According to the results of the second land survey in 2009, there were 53,690 hectares of construction land in Nanhai district, including 25,070 hectares of the RCCL, accounting for 46.69%. After the implementation of The Regulation and Administration for the Management of Collective Construction Land Use Rights Transfer in Guangdong Province (Serial No. 100), there were 88 parcels of RCCL with a total area of 145.87 hectares assigning their land use rights to land demanders. (Data source: Collective Asset Trade Platform, Land and Resources Bureau in Nanhai District). For ensuring transparency and openness of the RCCL market, the Nanhai district government established a collective asset trading platform in village collectives and sub-villages respectively in 2010, which was equipped with a trading platform system after all collective assets inventory and accounting.

3.2. Data Collection

According to the pilot construction of the RCCL market in Nanhai District, the “Building Urban and Rural Unified Construction Land Market” research group conducted a questionnaire survey on the RCCL market in Nanhai District. According to the theoretical hypothesis above, we designed the questionnaire. The content of the questionnaire mainly includes: the land use information of the RCEO, the basic information of the RCCL market transaction (model, location, area, object, etc.), the uncertainty of transaction behavior and transaction environment, the basic social and economic conditions of the RCEO. We adopted a simple random sampling method to select the survey sample. The investigator randomly selected the surveyed object (relevant person in charge of the rural collective economic organization) without prior notice. Each sample of the questionnaire takes parcels as a unit. During the investigation, 390 questionnaires were interviewed face-to-face, and 380 were returned, of which 372 were valid, accounting for 97.89% of the total sample.

3.3. The Characteristics of Land Sales Market and Land Rental Market in Nanhai District

3.3.1. The Contract Terms of the Land Sales Market and Land Rental Market Are Different

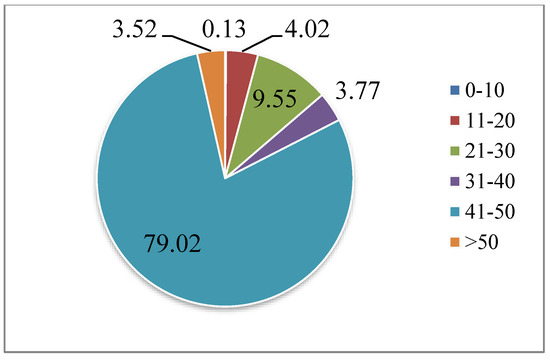

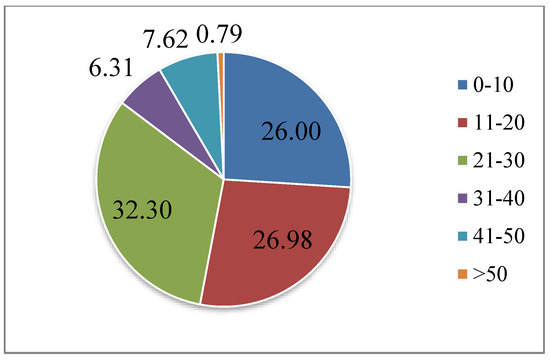

The main land-use patterns of the RCCL market in China are the land sales market and land rental market, which is typical and pioneering in Nanhai District, Guangdong Province. Cases through the land rental market are obviously more than those of the land sales market (Table 1). The contract duration of the land sales market is longer than the land rental market. The mean contract period of the land sales market is 46.405 years, and the mean contract period of the land rental market is 22.085 years. The contract duration of the land sales market is mainly between 41–50 years (Figure 3), while that of the land rental market is mostly below 30 years (Figure 4). To the supply side, long contract duration indicates they may lose long-term income expectations, and transaction uncertainty leads to high transaction costs. For the demanders, long-term investment in the RCCL market means that transferring land to other users may incur high transaction costs. Moreover, transactions will frequently happen in the land rental market. Frequent transactions give rise to transaction costs such as the negotiation costs, information collection costs, monitoring costs, and so on.

Table 1.

The characterize of the RCCL market in Nanhai District.

Figure 3.

The Proportion of Different Contract Period of Land Sales Market (%). Data source: Collective Asset Trade Platform in Nanhai District.

Figure 4.

The Proportion of Different Contract Period of Land Rental Market (%). Data source: Collective Asset Trade Platform in Nanhai District.

3.3.2. The Rights to Operating the Land Are Different

For the land rental market, the demand side just gets the land use right, cannot make over, mortgage, and obtain land value-added revenue, which is returned to the land supply side.

For the land sales market, the demand side gets the land-use property rights, can use, makeover, mortgage, become a shareholder when selling land, and obtain land value-added revenue.

The supply side (the RECO) will be confronted with the loss of land rights, which will influence the choice of the land rental market and land sales market.

3.4. Hypotheses

Asset specificity contains human capital specificity, material capital specificity, and location specificity. Transaction uncertainty includes behavior uncertainty and environment uncertainty.

Human capital specificity can be characterized as the population of collective economic organization and the percentage of leaders in collective economic organizations. Large members of the RCEO enhance the asset specificity. This mainly takes the self-organization of the RCEO into account. Higher self-organization cuts down the duration and frequency of transactions, and decreases the negotiation cost. However, a less simplified RCEO may increase negotiation costs and human costs. The sharp-sighted RCEO choose the land sales market for lowering the transaction costs and increasing the collective land income. So, we devise Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 1.

When the human capital specificity is higher, the RCEO prefers to choose the land sales market.

Material capital specificity is composed of the total rural land scale and trading land scale in the RCCL market. After the land shareholding system reform in Nanhai District in 1992, rural land (farmland and RCCL) and estate in the RCCL belonged to the collective asset operated by the RCEO. Compared to farmland, RCCL is more and more expensive and has become the major income source. The total rural land scale means the number of land reserve resources that can be converted to RCCL in the future. The larger scale of trading land leads to higher asset specificity. On the one hand, larger-scale land will easily be “locked in” for a particular purpose, and bring about high transaction costs for transferring to other use. On the other hand, a larger land scale increases the bargaining costs. The land sales market makes the RCEO get long-term operating income and decrease the loss of land idle, and reduce transaction costs. Furthermore, even though land rental markets do not permit perfect adjustment to the desired size of operation [41], the transaction costs incurred are smaller than those in land sales markets [7]. For land rental arrangements, tenants have few incentives to undertake long-term investments unless they receive the value of the investment back during the rental term or at its end [7]. So, we give Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 2.

The RCEO chooses the land sales market for large trading areas which may bring about higher material specificity.

Location specificity includes relative and absolute location attributes. Relative location attribute is the land-use type before transaction, while absolute location attribute is the distance from the location of the trading land to central town. For one thing, relative location attributes imply that a high agglomeration effect promotes transaction expectations, and the RCEO does not need to pay for the converting fees, which can shorten the transaction duration and improve market efficiency. For the other thing, the absolute location attribute manifests that the enterprise needs to pay higher rent for the collective land with a better location. The RCEO creates an option that the land rental market can terminate the contract and reduce the location specificity. Accordingly, another hypothesis can be presented.

Hypothesis 3.

The RCEO makes the land sales choice with the enterprise to weaken the location specificity and reducing the transaction costs.

Transaction behavior uncertainty is composed of the trading partner, government intervention, intermediary company participation, and the price bid way, which refers to transaction costs that may be caused by the uncertainties in the transaction process of the RCCL market. It is difficult to evaluate the performance of trading behavior [42], for instance, the trading object, government intervention, the price bid way, and so on. These factors may result in opportunistic and “rent-seeking”. Thence, the RCEO can alter the transaction object when the contract is expired and impair the transaction behavior uncertainty and lessen transaction costs. The hypothesis is as follows.

Hypothesis 4.

The land rental market can reduce transaction costs for short-term impact when the transaction process is with higher uncertainty of transaction behavior.

Transaction environment uncertainty includes land certificate, operating conditions, and funding status of enterprise. The trading parties are “rational-economic men”, they are prone to put up information that is a benefit to themselves and hide the unfavorable factor [43,44]. The uncertainty of transaction environment takes place, which may result in “moral risk” [45]. The trading resource loss for information asymmetry will increase the transaction costs [46,47]. Moreover, the lack of information on partners in markets makes it impossible to ascertain whether this is due to the contractual form or tenants’ inherent productivity [48]. For the land rental market, the RCEO has greater flexibility to transfer the use of land to more efficient producers with relatively low transactions costs and is less vulnerable to information asymmetry [4,7,49]. We put forward the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 5.

To some extent, choosing the land rental market can keep away the long-term uncertainty to reduce transaction costs.

Transaction frequency is the mean contract duration of statistical data divided by actual trading contract duration. The mean contract duration of the land sales market is 44, while it is 22 for the land rental market. Transaction cycle and transaction frequency also have an impact on market transaction costs. In a complete economic market, one transaction or independent transaction usually occurs. High frequency transactions will generate a series of problems, such as contract risk, incomplete contract, opportunism, etc. Therefore, high transaction frequency will lead to transaction costs [33]. For the land rental market, transferring land to other demanders is a better way to avoid high transaction costs. Thus, the hypothesis is as follows.

Hypothesis 6.

The land rental market choice is useful to decrease transaction costs resulting from frequent transactions.

3.5. Expected Impact of Key Explanatory Variables on Transaction Model Choice

Based on the theoretical framework, we developed a set of hypotheses about the transaction model choice equation. The dependent variable is the transaction model choice, the independent variables are factors of three attributes of transaction costs: asset specificity, transaction uncertainty, and transaction frequency. These factors were designed based on the transaction costs theory of Williamson [31,32]. Short definitions of the independent variables are summarized in Table 2, including means and standard deviations.

Table 2.

Definitions of variables and summary statistics (N = 372).

3.6. Econometric Model

Transaction model choice is a latent (unobserved) variable for transaction models, which is influenced by the variables above. Then we construct the econometric relationship between transaction models and the variables (1).

where denotes the variables of asset specificity and uncertainty. The random disturbance reflects the other factor that impact the transaction model choice except the transaction costs attributes.

Considering the type of independent variables, we analyzed the influencing factors of transaction costs attributes to the transaction model choice by establishing a Probit model, which is a binary selection model.

The matrix of the Probit model is defined as (2).

In Equation (2), the transaction model choice is selected as a binary discrete variable, and the choice of the land rental market is assigned a value of 0, and the choice of land sales market is assigned a value of 1. In the econometric model, we introduce a latent variable related to , then we get Equation (3).

Among them, the independent variables are the transaction costs attributes of the RCEO’s transaction model choice, is the coefficient to be estimated, and is a residual item that is independent of each other and follows the normal distribution. The corresponding expression is (4).

4. Results

We present the results from the Probit model of RCEO’s transaction model choice in Table 3.

Table 3.

Maximum Likelihood Estimation of the Probit Model for Transaction Model Choice (N = 372).

For the asset specificity dimension, the population of RCEO is a significant determinant of the transaction model choice. This has an intuitive and straightforward interpretation that more population means lower self-organization governance of the RCEO, which will result in opportunism and “rent-seeking” behavior and increase human specificity. The RCEO with lower self-organization chooses the land sales market for increasing the collective land income and then offsetting the transaction costs, which conform the Hypothesis 1.

Leader ratio positively affects the transaction model choice. The RCEO chooses the land sales market for that more leaders at the RCEO may bring more negotiation costs in the RCCL market transaction. Then, the RCEO can raise the collective land revenue by long-term land sales market, which can avoid land idle in the short-term land rental market. This result also proves Hypothesis 1. For the land sales market, the transaction contracts state that the rent will increase by 5% every five years.

Land trading scale positively influences the transaction model choice. The RCCL is mainly used as industrial and commercial land. Large-scale land can be caught in a certain purpose, which brings about high transaction costs if the land user changes the land-use pattern. Meanwhile, the RCEO will lose the land rights of large-scale land, and may negotiate for a long time with the supply side, which increases the transaction costs. Therefore, the RCEO choose the long-term land sales market for averting transforming land-use type, and lowering the land material capital specificity, which is a great test result of Hypothesis 2.

In terms of the location specificity, the industrial area agglomeration effect of the collective construction land can increase long-term earnings expectations, thus, the RCEO prefers to choose the land sales market just at the time when the pre-use is construction land. Moreover, the RCEO does not need paying for converting the land-use. In addition, the distance to the central town is a significant determinant of the likelihood of the transaction model choice. The closer to the central town of the trading collective construction land, the higher price it transacts for. Consequently, the trade land lock in the location and certain patterns, which give rise to high transaction costs. This has a straightforward interpretation that the RCEO squints towards choosing the land rental market just at a place where the trade land is close to the town center for high land rent and high investment. The results confirm Hypothesis 3.

At the uncertainty dimension, the risk-averse RCEOs are more likely to make the trading environment standardized and transparent. The RCCL market in Nanhai District developed in the 1990s, the initial transaction contract was verbal trading because the trading object was a member of the RCEO. Thence, transactions between the RCEO and members are less uncertain than non-members. Even though the RCEO chooses the land rental market, they also can get continuous income. The transaction may break off with non-members due to transaction uncertainty, which leads to loss of on-going land rent. Then the RCEO tends to choose the land sales market with non-members for a one-time fat profit. However, the model result does not confirm the theoretical hypothesis, which needs further study to give more explanation.

The government intervention has a positive and significant coefficient on the transaction model choice. The district government intervenes in the transaction process through rules supervision, which can lower the transaction uncertainty. Lower risk in the land sales market promotes transaction expectations.

The price bid way tends to have stronger preferences for the land rental market. Otherwise, the RCEO chooses the land sales market the competitive tender way and chooses the land rental market using the agreement way, which rejects Hypothesis 4. The competitive way is more open, fair, and impartial, but the agreement way is less transparent and with high transaction costs. However, in consideration of the trading partner, in the rental market, the trading partner is the RCEO member accounting for 17.24%, while in the land sales market, it is 5.3%. Thus we can know that the RCEO prefers to choose the land rental when they trade with RCEO members the agreement way, to lower transaction risk.

The RCEO consists of rational economic people who pursue the maximum benefit. So, they will learn the basic information of the trading partners before transactions. A negatively significant coefficient on the knowledge of the trade object’s operating conditions indicates that information asymmetry lowers transaction expectations. The RCEO chooses the land sales market without the information of transaction pattern as a result of one-time benefit. While the land rental market is a great choice for full information of the trade object’s operating conditions for the purpose of decreasing the information asymmetry because the demand side has lower risk aversion, which confirms Hypothesis 5.

The RCEO with basic information of the trade object’s financial condition tends to prefer the land sales market. The RCEO can get a one-time land benefit if the trading object is in good financial condition. However, the RCEO faces a moral risk without knowing the financial conditions. The land rental market is appropriate to reduce transaction uncertainty.

Transaction frequency significantly negatively influences transaction model choice. High frequent transactions give rise to frequent negotiation costs and bargaining costs. The RCEO chooses the land rental market to remove high transaction costs to other demanders. The result greatly explains Hypothesis 6.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

5.1. Conclusions

The RCCL market is a unique land market pattern for China’s land system development. The rental market is the main market model, while after 1999, the sales market model gradually grew. The State Council of the People’s Republic of China promulgated some pilots of the RCCL use rights transaction in 1999. However, there are different transaction rules for different market models, how to choose low transaction costs and high efficient RCCL market model is key to land use revenue, land use efficiency, land allocation efficiency and land use sustainability for the supply side. This paper was motivated by the fact that, even though many policies and regulations had been issued for standardizing the RCCL market transactions by central government and local government in China, “land lazy” and lower efficient use still happened. Such a “lazy” market may result from the inaccurate land transaction model choice. The empirical analysis for the Nanhai District, building on the theory framework of Williamson’s transaction costs where the asset specificity, uncertainty, and transaction frequency have a significant influence on the RCCL market model choice, allows us to draw some conclusions with the respect to the transaction attributes among the land sales market and rental market. This study is with little research and likely to be of interest to policymakers as well as researchers.

Firstly, the RCEO prefers to choose the land sales market when the RCCL market is with higher asset specificity, the land sales market can counteract transaction costs by creating land revenue for long-term investment. In addition, the land sales market has a longer period while the rental market produces a faster payback period, which empirically tests the framework of asset specificity in Figure 1 and greatly confirms Hypotheses 1–3. Higher asset specificity may restrict the land-use pattern and decrease the land-use efficiency of the rental market, in addition, it may result in lower land-use sustainability. In Nanhai District, the majority of local, traditional production industries are cover large areas and great locations in the land sales market, which gives rise to high transaction costs. However, these RCCL form an area agglomeration effect and promote market efficiency, and will get long-term investment for sustainable land use in the sales market.

Secondly, the rental market choice is more suitable to the RCCL market with higher transaction uncertainty. The rental market has a short-term contract period. High uncertainty means that the RCEO is confronted with high market risk, such as information asymmetry, then, they can change the transaction partner for decreasing the market risk and transaction costs. This conclusion is good empirical evidence for Hypotheses 4 and 5. For ensuring transparency and openness of the RCCL market, the Nanhai district government established a collective asset trading platform in 2010. Moreover, the transaction contract needs to regulate the pollution discharge status of the enterprise, which is for the improvement of the rural environment and enhancement of villagers’ life quality. However, achieving land policies has a greater reliance on pilot programs examined under local conditions [7].

Thirdly, the rental market is more adapted to high transaction frequency, to mitigate high transaction costs and risk of the land sales market, which empirically test Hypothesis 6.

5.2. Policy Implications

This article is to make a contribution to choosing the suitable market model with lower transaction costs, higher market efficiency, and sustainable rural land market, which is crucial for the RCEO to revitalize land use and increase farmers’ land revenue in Nanhai District. For land material specificity, the land sales market is a more appropriate choice when the trading land has a large area and great location, while the land rental market may be a restriction for specific investment because of the higher “lock in” effect. Therefore, the RCEO can make market rules according to types of industries for different land models, for the land sales market, the demand side should be a sunrise industry with long-term investment expectations. For the land rental market, the demand side can not just be restricted to the foodservice industry, retail department, and other small industries, which can be better for the lease of above-ground properties on the RCCL other than trading new pieces of the RCCL to decrease transaction costs and improve investment expectations.

As for the transaction uncertainty dimension, an open, fair, and just market environment is conducive to the safety of the RCCL market. Therefore, the RCEO can detail transaction rules for the land sales and rental market. The local government needs to announce regulations on the longest contract period and land development planning (floor area ratio, building density, floor height, etc.) of different land-use types for the land sales market and the land rental market. Moreover, the demanders should provide supporting information on the funding status and operation situation of the past 10 years, which can improve information symmetry and transparency, and reduce transaction costs and risks. All of these can be entrusted to the third-party appraisal company for a comprehensive report on the investigation of the demand side, which is lacking in the current RCCL market in China but is growing in the urban-owned land market.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, funding acquisition, T.Z.; software, data curation, K.H.; formal analysis, investigation, resources, supervision, A.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (72004084, 71904178), the Jiangxi Province Universities’ Humanities and Social Sciences Key Research Projects (JD20054), the Humanity and Social Science Foundation of the Chinese Ministry of Education (19YJC790185), the Jiangxi Province Natural Science Foundation Project (20181BAB211005).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Klein, B.; Crawford, R.G.; Alchian, A.A. Vertical integration, appropriable rents, and the competitive contracting process. J. Law Econ. 1978, 21, 297–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grout, P. Investment and wages in the absence of binding contracts: A Nash Bargaining Approach. Econometrica 1984, 52, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.E.; Zhang, A.L. Market efficiency under the arrangement of transaction rules of the RCCL market from the supply-side perspective. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K.; Xia, F. Assessing the long-term performance of large-scale land transfers: Challenges and opportunities in Malawi’s estate sector. World Dev. 2018, 104, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimach, A.; Dawidowicz, A.; Dudzińska, M.; Źróbek, R. An evaluation of the informative usefulness of the land administration system for the Agricultural Land Sales Control System in Poland. J. Spat. Sci. 2019, 15, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deininger, K.; Jin, S. Land Sales and Rental Markets in Transition: Evidence from Rural Vietnam (World Bank Policy Research Working, No. 3013); World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Deininger, K.; Binswanger, H. The Evolution of the World Bank’s Land Policy: Principles, Experience, and Future Challenges. World Bank Res. Obs. 1999, 14, 247–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guriev, S.; Kvasov, D. Contracting on time. Am. Econ. Rev. 2005, 95, 1369–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hart, O.; Moore, J. Contracts as reference points. Q. J. Econ. 2008, 123, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williamson, O. The Economic Institutions of Capitalism: Firms, Market and Relational Contracting; Free Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Masten, S.E.; Crocker, K.J. Efficient adaptation in long-term contracts: Take-or-pay provisions for natural gas. Am. Econ. Rev. 1985, 75, 1083–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschhausen, C.; Neumann, A. Long-term contracts and asset specificity revisited: An empirical analysis of producer- importer relations in the natural gas industry. Rev. Ind. Organ. 2008, 32, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boué, C.; Colin, J.P. Land certification as a substitute or complement to local procedures? Securing rural land transactions in the Malagasy highlands. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, V. Long-term relationships governed by short-term contracts. Am. Econ. Rev. 1988, 78, 485–499. [Google Scholar]

- Osei, O.A.; Henten, A. The land rental system and diffusion of telecom infrastructure in Ghana: An institutional and transaction economics approach. Eurasian Bus. Rev. 2017, 7, 183–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.X.; Zhang, X.L.; Wu, Y.Z.; Skitmore, M. Collective land system in China: Congenital flaw or acquired irrational weakness? Habitat Int. 2015, 50, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.; Zhu, D. A spatial and temporal analysis on land incremental values coupled with land rights in China. Habitat Int. 2014, 44, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.R. Land policy reform in China: Assessment and prospects. Land Use Policy 2003, 20, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.W. Land market forces and government’s role in expansion. Cities 2000, 17, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenberg, E.; Ding, C. Assessing farmland protection policy in China. Land Use Policy 2008, 25, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.L.; Wu, C.S.; Zang, S.Y. Modelling urban land use conversion of Daqing City, China: A comparative analysis of “top-down’’ and “bottom-up’’ approaches. Scotch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2014, 28, 817–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Zhu, J.M. Clarification of collective land rights and its impact on non-agricultural land use in the Pearl River Delta of China: A case of Shunde. Cities 2013, 35, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polman, N.B.; Slangen, L.H. An Institutional Economics Analysis of Land Use Contracting: The Case of the Netherlands. Inst. Sustain. 2009, 13, 267–290. [Google Scholar]

- Po, L. Redefining rural collectives in china: Land conversion and the emergence of rural shareholding co-operatives. Urban Study 2008, 45, 1603–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, G.; Deininger, K. Land Institutions and Land Markets; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 2014; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, M.A.; Brandt, L.; Rozelle, S. Property Rights Formation and the Organization of Exchange and Production in Rural China; Working Paper; University of Toronto, Department of Economics: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X. Ground-level bureaucrats as a source of intensification of rural poverty in china. J. Int. Dev. 1999, 11, 637–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrehiwot, D.B.; Holden, S.T. Variation in Output Shares and Endogenous Matching in Land Rental Contracts: Evidence from Ethiopia. J. Agric. Econ. 2019, 19, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.H.; Heerink, N.; Qu, F.T. Land fragmentation and its driving forces in China. Land Use Policy 2006, 23, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, A.L.; Deng, S.L. Research of the rural collective construction land market efficiency and influencing factors. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2018, 28, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O. The Mechanisms of Governance; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O. Public and private bureaucracies: A transaction cost economics perspectives. J. Law Econ. Organ. 1999, 15, 306–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alexander, E.R. A transaction-cost theory of land use planning and development control—Towards the institutional analysis of public planning. Town Plan. Rev. 2001, 1, 43–75. [Google Scholar]

- Deininger, K.; Jin, S.; Nagarajan, H.K. Determinants and Consequences of Land Sales Market Participation: Panel Evidence from India; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Coase, R. The nature of the firm. Economica 1937, 4, 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O. Comparative economic organization: The analysis of discrete structural alternatives. Adm. Sci. Q. 1979, 36, 269–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williamson, O. Transaction-cost economics: The governance of contractual relations. J. Law Econ. 1991, 22, 3–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, E.R. How Organization Act Together: Inter-Organizational Coordination in Theory and Practice; Gordon & Breach Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Grandori, A. An organizational assessment of inter-firm coordination models. Organ. Stud. 1997, 18, 897–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.K. The Making of Economic Policy: A Transaction-Cost Politics Perspective; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Skoufias, E. Household Resources, Transaction Costs, and Adjustment through Land Tenancy. Land Econ. 1995, 71, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Control-Organizational and economic approaches. Manag. Sci. 1985, 31, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commons, J.R. Institutional Economics; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.G.; Vollmann, T.E. The hidden factory. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1985, 55, 50–142. [Google Scholar]

- Hirshleifer, J.; Riley, J.G. The analytics of uncertainty and intermediation: An expository survey. J. Econ. Lit. 1979, 17, 1375–1421. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlman, C.J. The problem of externality. J. Law Econ. 1979, 22, 62–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kreps, D.M. A Course in Microeconomic Theory; Harvester: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Deininger, K.; Ali, D.A.; Alemu, T. Productivity effects of land rental market operation in Ethiopia: Evidence from a matched tenant–landlord sample. Appl. Econ. 2013, 45, 3531–3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masterson, T. Land Rental and Sales Markets in Paraguay; The Levy Economics Institute Working Paper No. 491; The Levy Economics Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).