Emerging Diffusion Barriers of Shared Mobility Services in Korea †

Abstract

1. Introduction

Research Question: What are the new types of innovation barriers besides technological barriers?

2. Related Background

2.1. Sharing Economy and Shared Mobility Services

2.2. Traditional Innovation Barriers

2.3. Emerging Innovation Barriers

2.4. Mobility Innovation Barriers: A Case Study of TADA

3. Method

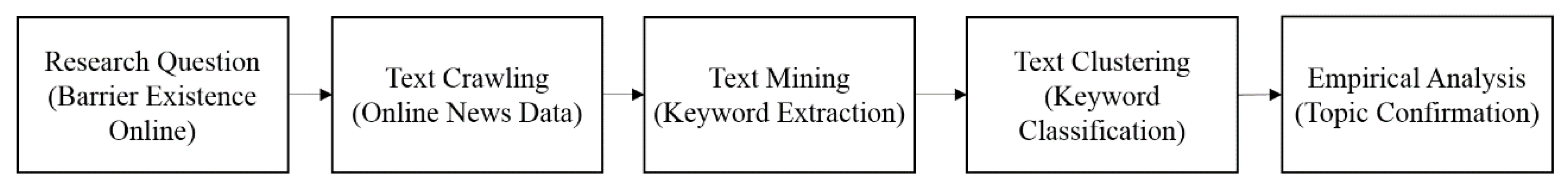

3.1. Research Procedure and Data

3.2. Analysis Methods

4. Results

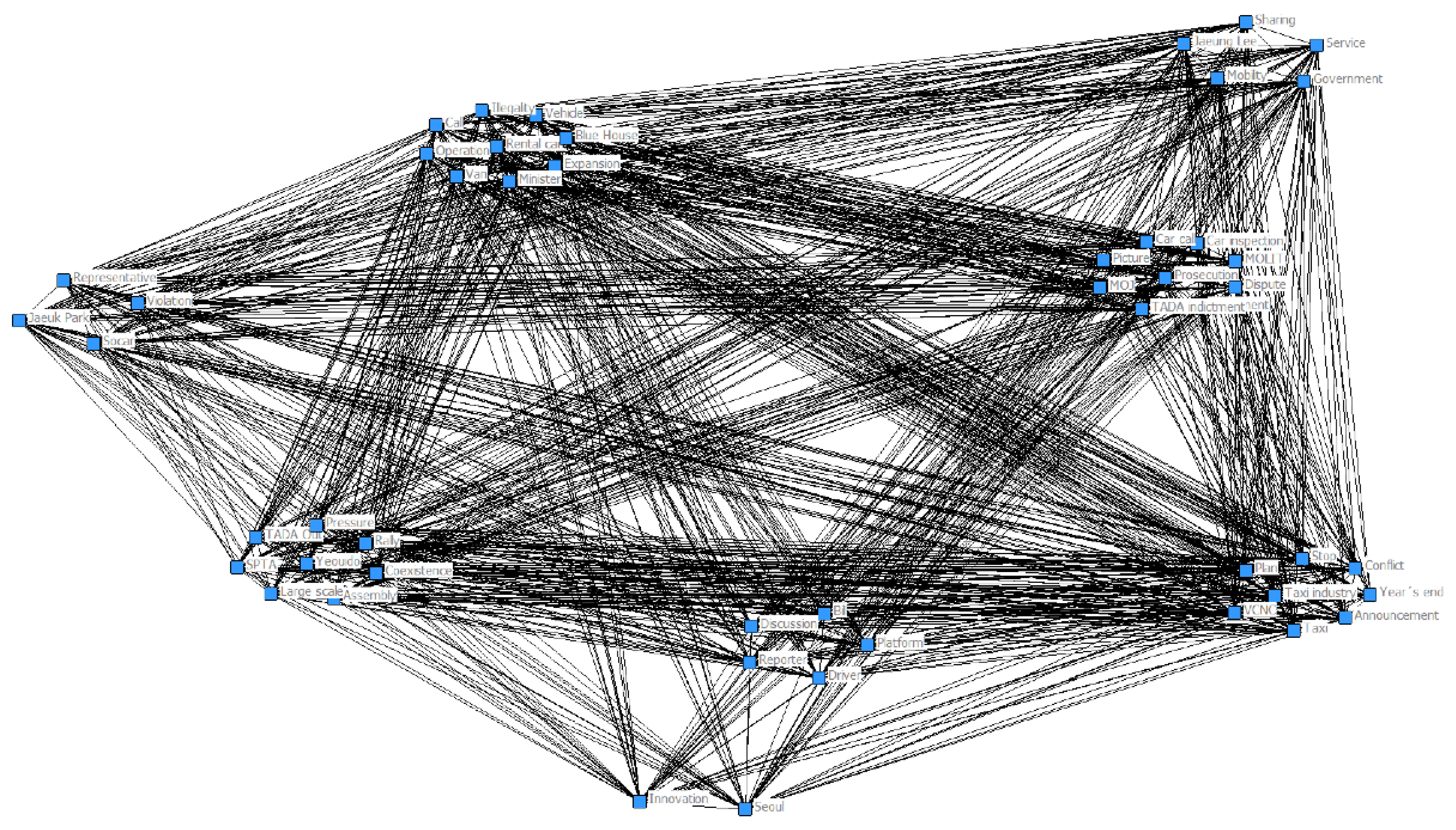

4.1. Keyword Frequency and Degree Centrality

4.2. CONCOR Analysis

5. Discussion

5.1. Findings

5.2. Contributions

5.3. Limitations and Further Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Torre-Bastida, A.I.; Del Ser, J.; Laña, I.; Ilardia, M.; Bilbao, M.N.; Campos-Cordobés, S. Big Data for transportation and mobility: Recent advances, trends and challenges. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2018, 12, 742–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, H. Digital Transformation of Automobile and Mobility Service. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Field-Programmable Technology (FPT), Naha, Japan, 10–14 December 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.-H.; Kim, S.-I. A study on User Experience of Mobility Platform Service-Focused on kakao Taxi and Tada. J. Digit. Converg. 2019, 17, 351–357. [Google Scholar]

- Ji-hye, J. No Startups in Korea if Tada is Illegal. The Korea Times, 14 November 2019. Available online: https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/tech/2019/11/133_278168.html (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- Clewlow, R.R.; Mishra, G.S. Disruptive Transportation: The Adoption, Utilization, and Impacts of Ride-Hailing in the United States; UC Davis: Davis, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Yu, W.; Griffith, D.; Golmie, N. A survey on industrial Internet of Things: A cyber-physical systems perspective. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 78238–78259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberato, P.; Alen, E.; Liberato, D. Smart tourism destination triggers consumer experience: The case of Porto. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2018, 27, 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, M.K.; Oh, J.; Lee, H. Understanding travelers’ behavior for sustainable smart tourism: A technology readiness perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessig, L. Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy; Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-J.; Park, J.-W.; Jo, D.-H. An Empirical Study on Success Factors of Sharing Economy Service. J. Korea Contents Assoc. 2016, 16, 214–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pouri, M.J.; Hilty, L.M. Conceptualizing the digital sharing economy in the context of sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Kim, Y.; Lee, Y.; Ryu, D. Sharing Economy Platforms and Tying. Korean Manag. Rev. 2020, 49, 499–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botsman, R.; Rogers, R. Whats Mine Is Yours: The Rise of Collaborative Consumption; Harper Business: New York, NY, USA; Collins: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.A.; Rashid, M.M.; Hossain, M.S.; Hassanain, E.; Alhamid, M.F.; Guizani, M. Blockchain and IoT-based cognitive edge framework for sharing economy services in a smart city. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 18611–18621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, M.; Winter, S.; Krüger, A. A continuous representation of ad hoc ridesharing potential. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2016, 17, 2832–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, S.; Sheth, J.N. Consumer Resistance to Innovations: The Marketing Problem and its Solutions. J. Consum. Mark. 1989, 6, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Stellner, W.H. Psychology of Innovation Resistance: The Less Developed Concept (LDC) in Diffusion Research; University of Illinois: Champaign, IL, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ram, S. A model of innovation resistance. Acr. N. Am. Adv. 1987, 14, 208–212. [Google Scholar]

- Ellen, P.S.; Bearden, W.O.; Sharma, S. Resistance to technological innovations: An examination of the role of self-efficacy and performance satisfaction. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1991, 19, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holak, S.L.; Lehmann, D.R. Purchase intentions and the dimensions of innovation: An exploratory model. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. Int. Publ. Prod. Dev. Manag. Assoc. 1990, 7, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laukkanen, P.; Sinkkonen, S.; Laukkanen, T. Consumer resistance to internet banking: Postponers, opponents and rejectors. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2008, 26, 440–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.-T.J.; Sheu, C. Application of the theory of planned behavior to green hotel choice: Testing the effect of environmental friendly activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-W.; Kankanhalli, A. Investigating user resistance to information systems implementation: A status quo bias perspective. Mis Q. 2009, 33, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, A.; Laumer, S.; Weitzel, T. Who influences whom? Analyzing workplace referents’ social influence on IT adoption and non-adoption. J. Inf. Technol. 2009, 24, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molesworth, M.; Suortti, J.P. Buying cars online: The adoption of the web for high-involvement, high-cost purchases. J. Consum. Behav. Int. Res. Rev. 2002, 2, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleijnen, M.; Lee, N.; Wetzels, M. An exploration of consumer resistance to innovation and its antecedents. J. Econ. Psychol. 2009, 30, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabino, B.; Salis, S.; Assorgia, A. Application of mobility management: A web structure for the optimisation of the mobility of working staff of big companies. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2012, 6, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Knetsch, J.L.; Thaler, R.H. Anomalies: The endowment effect, loss aversion, and status quo bias. J. Econ. Perspect. 1991, 5, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidenreich, S.; Spieth, P. Why innovations fail—The case of passive and active innovation resistance. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2013, 17, 1350021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Geest, L.; Heuts, L. Barriers to innovation. In Micro-Foundations for Innovation Policy; Nooteboom, B., Stam, E., Eds.; Amsterdam University Press: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 173–198. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.J.; Muhanna, W.A.; Klein, G. User resistance and strategies for promoting acceptance across system types. Inf. Manag. 2000, 37, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschheim, R.; Newman, M. Information systems and user resistance: Theory and practice. Comput. J. 1988, 31, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holverson, C. Overcoming Barriers to Adoption for Innovations in Policy: Reflections from the Innovation Toolkit. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2017, 11, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, H.; Lee, H. The Diffusion Barriers of AI Mobility Service: The Case of TADA. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Information and Communication (ICAIIC), Fukuoka, Japan, 19–21 February 2020; pp. 666–670. [Google Scholar]

- Jun-suk, Y. Mobility Startups Protest Government’s Ride-Sharing Reform Plan. The Korea Herald, 17 July 2019. Available online: http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20190717000730 (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- Kang, H.M. Controversy Deepens over Accepting Ride-sharing Services or Protecting the Taxi Industr. The Korea Bizwire, 29 May 2019. Available online: http://koreabizwire.com/controversy-deepens-over-accepting-ride-sharing-services-or-protecting-the-taxi-industry/138113, (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- Song, K. Taxi Drivers Go to War against Tada Van-Hailing App. Korea JoongAng Daily, 19 February 2019. Available online: https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/news/article/article.aspx?aid=3059627 (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- Ji-hye, J. Taxi Drivers up in Arms against Tada Verdict. The Korea Times, 20 February 2020. Available online: https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/tech/2020/02/133_283786.html (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- Byung-yeul, B. Tada Forced to End Van-Hailing Service in April. The Korea Times, 11 March 2020. Available online: https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/tech/2020/03/133_286018.html (accessed on 7 April 2021).

- Meyer, D.; Hornik, K.; Feinerer, I. Text mining infrastructure in R. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25, 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Jianping, C.; Jie, X. Prospecting information extraction by text mining based on convolutional neural networks–a case study of the Lala copper deposit, China. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 52286–52297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J.B.; Barnett, G.A. Exploring the presentation of HPV information online: A semantic network analysis of websites. Vaccine 2015, 33, 3354–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Luo, Y. Degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and closeness centrality in social network. In Proceedings of the 2017 2nd International Conference on Modelling, Simulation and Applied Mathematics (MSAM2017), Bangkok, Thailand, 26–27 March 2017; pp. 300–303. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, W.; Seary, A. Eigen analysis of networks. J. Soc. Struct. 2000, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, C.A.S.; de Salles Hue, N.P.M.; Berssaneti, F.T.; Quintanilha, J.A. An overview of shared mobility. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xu, J.; Liu, X.; Sun, C.; Duan, Z. Use of shared-mobility services to accomplish emergency evacuation in urban areas via reduction in intermediate trips—Case study in Xi’an, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.; Rashidi, T.H.; Rose, J.M. Preferences for shared autonomous vehicles. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2016, 69, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Shared Resource | Companies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Korea | Global | ||

| Traffic | Vehicles | TADA, Kakao T, SOCAR, Udigo, GreenCar, Poolus | UBER, ZipCar |

| Bicycles | Kakao T bike, PurunBike | Velib, Barclay Cycle Hire | |

| Goods | Used goods | Auction, G market, 11st | Ebay, Craigslist, Flippid |

| Rental products | Libpia, The Shared Library | Chegg, Zookal | |

| Space | Office space | WeWork | Sharedspace |

| Accommodation | Kozaza | AirBnB | |

| Finance | Crowdfunding | Popfunding, Ssiatfunding | Kickstarter, Indiegogo |

| Classification | Features |

|---|---|

| Ride-Hailing (Car Hailing) | Connecting services to local taxi driver Like a call taxi system |

| Ride-Sharing (RS) | Connecting services to enrolled drivers (or company that owns automobiles or enrolls people for driving) Able to carpool with other passengers (carpooling) Drivers have their own vehicles |

| Car-Sharing (CS) | Connecting services to enrolled driver or company driver Commonly uses vehicles leased by the company Sharing service for automobiles (like a short-term car lease) |

| Classification | Features | |

|---|---|---|

| Arro | RH | Linked with internal taxi platform Uses stabilized taxi terminals and payment system |

| BlaBlaCar | RS | Drivers can determine who rides with them Operation of a detailed classification system for driver‘s preferences Exclusive options for female drivers |

| Bridj | RH | Utilizes public transportation routes (bus) Operates around a pick-up point Special access for people with physical challenges |

| Cabify | RS | Passengers can choose trip preferences Option to reserve or schedule a ride |

| Curb | RH | Utilizes existing taxi drivers Requires drivers to have insurance Provides reservation and tracking for vehicles |

| Didi Chuxing | RS/RH/CS | Collaborates with the taxi industry Offers a variety of service options (taxi-hailing or ridesharing in a personal vehicle or a rental company’s car) Services can be provided in conjunction with corporate platforms such as Tencent or Alibaba |

| Flywheel | RH | Linked with taxi service platform Separate payment system from taxi platform |

| Gett & Juno | RS | Drivers are required to have considerable driving expertise Different payment systems based on region Discounts for off-peak rides |

| Gokid | RS | Ride-sharing system for busy parents Utilizes trust relationships, such as neighbors and coworkers Journey tracking is available in real-time for parents Works on mutual favors (no payment) |

| Grab | RS | Offers options using local public transportation Real-time feedback on driver‘s experience |

| Hitch | RS | Drivers can post their schedule in advance Ride reservation |

| LYFT | RH | Drivers must pass a background check Passengers indicate satisfaction with the ride Additional options available to reduce waiting time |

| OLA | RS | In affiliation with local transportation such as rickshaws in India Provides real-time tracking of vehicle‘s driving path |

| Uber | RH | Expanded services beyond ridesharing Active rating system for driver assessment Available for people with pets Option to add multiple drop-off points |

| Via | RS | If necessary, provides the driver with a vehicle rental Can be linked to passengers on the same route |

| Wingz | RS | Passengers can book a trip up to two months ahead of time Passengers can select their preferred driver directly Flat rate costs (no hidden fees and surcharges) |

| Ztrip | RS/CS | Drivers can use their personal vehicle or a Ztrip rental Ability to set customized pick-up vehicle setting |

| Keyword | Frequency | Degree Centrality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Rank | Value | Rank | |

| Service | 815 | 1 | 0.042 | 2 |

| Indictment | 467 | 2 | 0.033 | 6 |

| Taxi | 442 | 3 | 0.050 | 1 |

| Prosecution | 426 | 4 | 0.039 | 4 |

| Representative | 344 | 5 | 0.025 | 10 |

| Government | 341 | 6 | 0.042 | 3 |

| Assembly | 326 | 7 | 0.026 | 9 |

| Seoul | 292 | 8 | 0.022 | 13 |

| Innovation | 289 | 9 | 0.027 | 8 |

| Vehicle | 288 | 10 | 0.022 | 14 |

| Illegality | 266 | 12 | 0.025 | 11 |

| Call | 266 | 11 | 0.005 | 50 |

| Dispute | 252 | 13 | 0.025 | 12 |

| Taxi industry | 212 | 14 | 0.027 | 7 |

| Platform | 201 | 15 | 0.017 | 19 |

| Rally | 195 | 16 | 0.017 | 21 |

| Reporter | 192 | 18 | 0.036 | 5 |

| Mobility | 192 | 17 | 0.021 | 15 |

| VCNC | 188 | 19 | 0.017 | 20 |

| Car inspection | 180 | 20 | 0.017 | 22 |

| Operation | 179 | 21 | 0.017 | 18 |

| Van | 174 | 22 | 0.017 | 24 |

| Coexistence | 161 | 23 | 0.008 | 42 |

| Rental car | 156 | 24 | 0.021 | 16 |

| Conflict | 153 | 25 | 0.017 | 23 |

| Jaeuk Park | 151 | 26 | 0.009 | 40 |

| Yeouido | 147 | 27 | 0.006 | 49 |

| MOLIT | 142 | 28 | 0.021 | 17 |

| Socar | 140 | 29 | 0.015 | 28 |

| Blue House | 138 | 31 | 0.014 | 30 |

| Car call | 138 | 30 | 0.007 | 48 |

| MOJ | 137 | 32 | 0.016 | 26 |

| Bill | 134 | 33 | 0.011 | 37 |

| Stop | 127 | 34 | 0.011 | 36 |

| TADA Out | 125 | 35 | 0.008 | 43 |

| Expansion | 124 | 36 | 0.011 | 38 |

| Plan | 119 | 37 | 0.013 | 32 |

| TADA indictment | 112 | 38 | 0.012 | 35 |

| Large scale | 109 | 39 | 0.008 | 45 |

| SPTA | 108 | 40 | 0.013 | 31 |

| Pressure | 107 | 41 | 0.009 | 39 |

| Picture | 105 | 43 | 0.016 | 25 |

| Minister | 105 | 42 | 0.012 | 34 |

| Sharing | 103 | 44 | 0.007 | 46 |

| Driver | 99 | 45 | 0.014 | 29 |

| Jaeung Lee | 97 | 47 | 0.008 | 41 |

| Violation | 97 | 46 | 0.007 | 47 |

| Year’s end | 96 | 48 | 0.008 | 44 |

| Announcement | 89 | 49 | 0.015 | 27 |

| Discussion | 89 | 50 | 0.013 | 33 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, S.; Lee, H.; Son, S.-W. Emerging Diffusion Barriers of Shared Mobility Services in Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7707. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147707

Kim S, Lee H, Son S-W. Emerging Diffusion Barriers of Shared Mobility Services in Korea. Sustainability. 2021; 13(14):7707. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147707

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Sungwon, Hwansoo Lee, and Seung-Woo Son. 2021. "Emerging Diffusion Barriers of Shared Mobility Services in Korea" Sustainability 13, no. 14: 7707. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147707

APA StyleKim, S., Lee, H., & Son, S.-W. (2021). Emerging Diffusion Barriers of Shared Mobility Services in Korea. Sustainability, 13(14), 7707. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147707