Abstract

The aim of the paper is to identify the mechanisms shaping the quality of life of the residents of poor neighborhoods based on the example of a deprived area of Łódź city center. To analyze this multidimensional phenomenon, the capability approach is used with a special focus on conversion factors that limit the pursuit of preferred lifestyles. Based on 80 in–depth interviews with residents and register data from public authorities (at the building level, which enables presenting the detailed spatial distribution of the analyzed issues), individual trajectories in the form of individual mechanisms have been established and then aggregated. The aggregation is presented as a web of social exclusion. The collected information has allowed the author to create a categorization of conversion factors in degraded areas that take into account their interrelationships and complex cause–effect mechanisms. The classification is constructed using the following categories: housing conditions, economic wealth, knowledge and skills, norms, attitudes and social capital, work environment, and life conditions (defined mainly as access to public services and space). Combining quantitative data (at the building level) with qualitative data provided the author with crucial input for the identification of specific public policy actions that can affect conversion factors.

1. Introduction

The aim of this paper is to identify the mechanisms shaping the quality of life (QoL) of residents of poor neighborhoods using the example of a deprived area of the city center of Łódź (Poland). The core concept of the paper is based on three pillars: the QoL (first pillar), the effects generated by the neighborhood (second pillar), and the effects placed within a specific context of the post–industrial municipality of Łódź. It is assumed that each of the three pillars influences the others.

The concept of quality of life is very complex and multidimensional. There are many definitions of quality of life, and there are many approaches to assessing quality of life based on different conceptual and measurement frameworks. An interesting proposal for analyzing individual quality of life was made by Sen [1,2,3,4,5] as part of his capabilities approach, in which he defines quality of life in terms of the capability to achieve valuable functionings. In this paper, this concept will be used to analyze the individual QoL of the residents of poor neighborhoods (the micro perspective).

There is also a variation in understanding the concept of neighborhoods, which are considered in different studies as a place, as a community or as a policy unit—as Baffoe [6] outlined in his review paper. Usually, neighborhoods are recognized that are where people reside and spend much of their time. For people living in urban areas, it is argued that neighborhoods are places that determine their quality of life [7]. They are also considered as the best geographical units for studying and understanding behavioral characteristics and social processes [6]. Poor urban neighborhoods—which are sometimes also called deprived, disadvantaged, or socially excluded neighborhoods—have complex social, economic, and physical conditions. The poor neighborhoods or more generally urban marginality are also seen from the macro perspective of the advanced dynamic of capitalism and considered as product of the approach taken to achieving a developed state [8,9,10].

These neighborhoods have been targeted by public policies in the EU. The emphasis of these policies has shifted away from improving the physical conditions of these neighborhoods, and towards enhancing the life chances of the most disadvantaged groups living in these areas. This reasoning is in line with the capability approach, as these enhanced life chances (capabilities) contribute to improvements in the QoL in these areas. While physical upgrades are easier to achieve, at least in the short run, implementing social changes that result in improvements in the quality of life of the residents in these neighborhoods requires complex actions engaging all stakeholders [11].

Thus, the complexity of negative phenomena in poor neighborhoods overlaps with the already multidimensional phenomenon of QoL. The analysis presented in this paper is conducted in the context of the municipality of Łódź, which has been struggling with poverty concentration zones for decades as a result of the city’s post–industrial history and poor housing conditions. The nature of the poor neighborhoods within the Łódż city center, the increased risk of social exclusion among the residents of these neighborhoods, as well as the multidimensionality and complexity of QoL raise questions about cause–and–effect relationships between various phenomena, as it may be assumed that poor QoL is the result of the individual features and behaviors of the analyzed residents, and of the features of the area where they live. The presence of these phenomena and their interrelationships may lead to a deterioration in QoL and an increased risk of social exclusion for the people living in these degraded areas. Because a multitude of interconnected phenomena affect the QoL (and social exclusion) of the residents of these neighborhoods, analyzing QoL in such contexts can be difficult. There is therefore the need to develop a conceptual framework to describe how these phenomena affect QoL, which is proposed in this article.

The paper consists of several parts. First, the theoretical framework is presented based on the QoL of the residents of poor neighborhoods, with a special focus on the capability approach. Then, some comments on neighborhood effects are made, which play a significant role for urban marginality. Next, the historical and socio–political context of the Łódź municipality is described. In the Materials and Method section, the research design and data sources are presented. In the results section, the sequence of the analysis and its empirical findings were described. The paper is ended with the discussion on the conclusions, and the public policy recommendations based on the observed results of the empirical analysis.

1.1. Quality of Life

As a general concept, QoL has been studied in many fields, including in economics, political science, psychology, philosophy, and medical science. The concept of QoL first appeared in the public discourse starting in the 1960s as an alternative indicator for meeting the prevailing social development goals, which were at that time defined as improvements in material living conditions [12]. There is no single, commonly accepted definition of quality of life. An individually–referenced definition of QoL has, for example, been provided by Schalock, Keith, Verdugo, and Gomez [13], who described QoL as a multidimensional phenomenon composed of core dimensions influenced by personal characteristics and environmental factors. The authors argued that the core dimensions of QoL are the same for all people, although the relative value and importance of these dimensions may vary between individuals.

Alongside these various definitions, there are different tools for measuring QoL [14,15,16,17]. The most complex and precise QoL measurement concept was provided by the final report of the Sponsorship Group “Measuring Progress, Well–being and Sustainable Development” and the Task Force on “multidimensional measurement of quality of life”, which was accepted by the European Statistical System Committee [18,19]. This proposal is an extension of the QoL measurement concept of Berger–Schmitt and Noll [20], who operationalized it within the framework of the European System of Social Indicators, which is, in turn, based on the recommendations of the Report on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress [21]. Those reports emphasized the multidimensional character of QoL, as well as the need to combine subjective and objective measures in assessing QoL. Moreover, the reports clearly stated that QoL should be assessed at both the individual and the community level. In its final report, the Task Force on “multidimensional measurement of quality of life” identified nine dimensions to be measured within the framework of the European Statistical System [19]; i.e., material living conditions, productive or main activity, health, education, leisure and social interactions, economic and physical safety, governance and basic rights, natural and living environment, and overall experience of life. Each dimension is comprised of a set of subjective and objective indicators. This system of indicators can be used to analyze different aspects of life within each dimension and how they change over time, and to assess and compare the QoL of individuals or households. However, this system does not provide an explicitly formulated guide to operationalizing the measurement, or a synthetic measure of QoL.

A very interesting method for assessing QoL is provided by the capability approach, which was developed and refined by Amartya Sen as a framework for describing and measuring individual well–being [2,4,5,22,23,24]. This framework has been synthesized and practically applied by various authors in a wide variety of fields [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. The capability approach is based on the assumption that it is not access to commodities themselves that is crucial for individuals to achieve a high quality of life and their desired lifestyle, but rather the properties of those commodities. It is important to keep in mind that not all capabilities have to be generated from goods or services [27]. For example, being a respected member of a community only requires the respectful behavior of other community members. According to Nussbaum and Sen [36], a person’s capability to live a good life can be defined as the individual’s capability to achieve valuable functionings, whereby functionings represent parts of the state of the person. In other words, the term capabilities refers to an individual’s effective possibilities of realizing achievements and fulfilling expectations; whereas the term functionings refers to the “beings and doings” of a person, and thus to the individual’s realized achievements and fulfilled expectations.

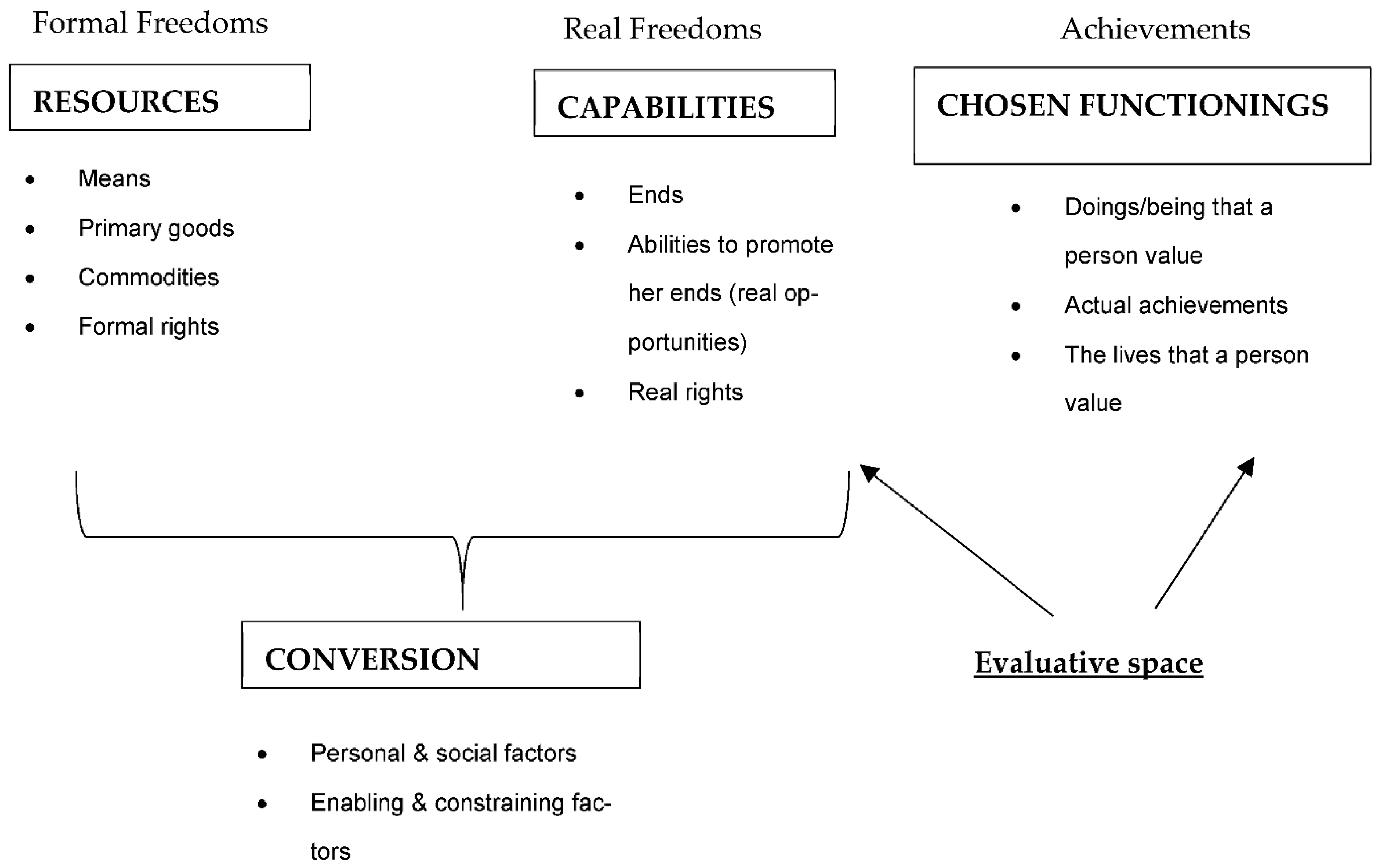

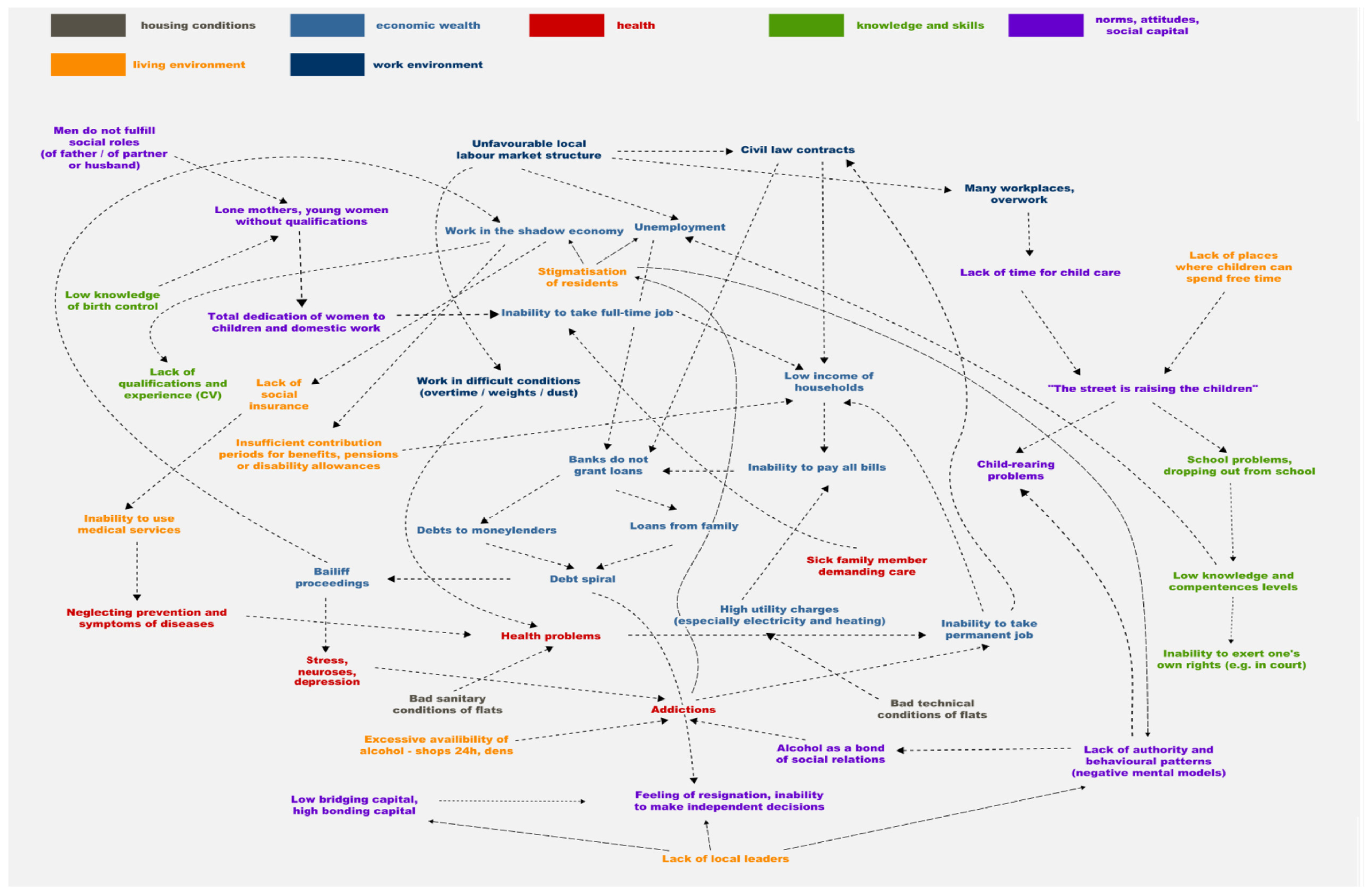

A graphical illustration of the relationship between commodities, capabilities, and functionings using the key concepts of the capability approach is provided in the Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Capability approach—basic concepts and relations. Source: [37].

In order to transform commodities into capabilities, three sets of conversion factors—personal, social, and environmental—are introduced [27,38] Conversion factors cannot be defined in a straightforward manner [39]. They are commonly identified by listing examples, and by presenting a taxonomy that divides them into the three categories of personal, social, and environmental [24,27,28,40,41]. Conversion factors are often described through their classifications, but these are not definitions per se. Thus, differentiating conversion factors from choices can be difficult. Sebastianelli [39] also argued that conversion factors should be analyzed as a whole, rather than individually; and suggested that the features of individuals’ lives become conversion factors only through their interactions with one another. Personal conversion factors (personal characteristics, such as metabolism, physical condition, intelligence, or gender) influence the types and degrees of capabilities a person can generate from commodities. By contrast, social conversion factors come from the society in which a person lives (characteristics of social settings, social institutions, and power structures, such as social norms, public policies, societal hierarchies, rule of law, and political rights). Environmental conversion factors emerge from the physical or built environment in which a person lives (environmental characteristics, such as climate, infrastructure, institutions, and public goods).

The achieved functionings of individuals are the result of their personal choices from the available capabilities, and are subject to personal preferences, social pressures, and other decision–making mechanisms. Moreover, people’s achieved functionings are constrained by personal, social, and environmental characteristics [27,42]. People must have equal opportunities to function in their preferred way [2], as it is only then that they are free to determine their capabilities—i.e., their potential ways of functioning—and to maximize their quality of life in accordance with these capabilities. It is also assumed that the effective freedom “to be and to do” is essential for assessing these capabilities.

In the context of Sen’s capability approach, social exclusion can be understood as the impossibility of achieving preferred functionings [4]. Having a limited choice of capabilities can lead to deprivation and to social exclusion. Thus, the process of social exclusion leads to a state of social exclusion, which can be interpreted as being deprived of some important functionings [43].

In this article, the capability approach will be used to examine the quality of life of a specific group of people—namely, residents of poor neighborhoods—who face an increased risk of social exclusion as a result of the presence of a number of negative social phenomena in these areas, including poor health, economic, technical, and infrastructural conditions. In this paper the QoL is treated as the multidimensional phenomenon. However, the analyses of the QoL are conducted within the very specific context of the place that generates the mechanisms of social exclusion to which the inhabitants are also exposed. The approach is described in the next subsections.

1.2. Neighbourhood Effects

The existence of socially disadvantaged neighborhoods is to a large degree the result of overall social inequalities in society [44] and unequal access to different community assets [40], which are multiplied by the specific local conditions. Poor neighborhoods or more generally urban marginality can be analyzed both from an individual (micro) and socio–economic and political (macro) perspective.

From a macro perspective, urban marginality in advanced societies was deeply analyzed by Wacquant [8,9,10], who highlighted four logics (mechanisms) that together produce the phenomenon of deprived urban areas. These are: macro societal drift towards inequality, changes in wage labor relations (elimination of low–skilled jobs due to automatization and foreign labor competition), retrenchment of welfare states, and the spatial concentration and stigmatization of poverty. Wacquant argues [8,9,10] that to cope with urban marginality, societies face three alternatives: they can patch up existing programs of the welfare state, criminalize poverty, or institute new social rights that sever subsistence from performance in the labor market.

From an individual (micro) perspective, poor neighborhoods are mostly analyzed through social exclusion. The concept of social exclusion means that the vulnerable groups living in these neighborhoods are excluded from basic rights, including access to income, housing, employment, services, political action, and administrative attention [45,46]; which, in turn, leads these groups to experience limitations in achieving their desired lifestyles, and thus to have low quality of life. Social exclusion is seen as a set of dynamic processes that decrease the life chances of vulnerable groups over time [6,47,48]. Many previous studies have highlighted the strong relationship between individual and local conditions (defined both by societal relations, and by access to employment and to various services). Local societies and individuals can achieve their growth potential only when they support and enhance each other [49]. While deprived neighborhoods provide living space for many vulnerable groups, they also expose these groups to additional threats that could lead to further social exclusion. These dynamics ultimately result in an expansion of the gap between these groups and the mainstream of society. Poor neighborhoods also strongly influence growth at the city level [50]. Research has shown that the residents of deprived neighborhoods spend most of their time in these neighborhoods [51,52], which limits their opportunities for engagement in wider networks that could enable them to function outside the neighborhood. Thus, poor neighborhoods are characterized by a wide range of negative phenomena that mutually reinforce each other, which, in turn, tend to exacerbate the social exclusion of the residents.

The quality of life in poor neighborhoods, which is often the subject of regeneration processes, is a very broad and multidimensional field of research. The most prominent branch of this research focuses on the neighborhood effects in different life domains, including in the context of social exclusion, and especially among disadvantaged groups [37,53,54,55]. Many to these studies identified racial and migration issues in poor neighborhoods as social exclusion factors [56,57,58,59,60,61,62]. It appears, however, that degraded areas have strong neighborhood effects even if racism and migration issues are not present. People living in deprived areas with concentrated poverty (and with many other social problems) are especially likely to be exposed to neighborhood effects in a range of domains, including housing, mental and physical health, education, employment and working conditions, life satisfaction, and the general living environment for overviews, see, e.g., [63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74]. Social networks and social capital have been identified as crucial mechanisms of neighborhood effects, as they enable people to function in their daily lives in particular neighborhoods [64,72,75,76,77]. A somewhat less prominent issue in this field is that of the residents’ attachment to their local environment. Place attachment refers to the emotional bonds people develop through their behavioral, affective, and cognitive ties to social and physical environments [77,78,79,80,81]. Despite the large body of literature on neighborhood effects in particular domains, the number of studies that have provided a comprehensive multidimensional assessment of quality of life is more limited. In this context, the interesting study done by Omuta [82], who proposed six environmental dimensions that were measured at the neighborhood level for Benin City, Nigeria, is worth mentioning. He derived a composite conceptual index of quality of life from the six dimensions, and compared the index values of the analyzed areas.

The literature on neighborhood effects also refers to analyses of the effectiveness of the different tools, programs, and policies that have been implemented by various actors with the aim of improving the life chances of the residents of those neighborhoods. The ultimate goal of these actions is to decrease the negative neighborhood effects, e.g., [11,52,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92]. In this context, the results of the “Moving to opportunity” project (MTO) should be mentioned. This project is a randomized housing mobility experiment sponsored by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Starting in 1994, the MTO provided 4600 low–income families with children living in public housing in some of the most disadvantaged urban centers the chance to move to private market housing in much less distressed communities. The results of the experiment showed that the neighborhoods in which children grew up shaped their outcomes in adulthood, but also that social mobility varied across U.S. cities, and between neighborhoods within these cities. In this context, social mobility was measured by income and other key indicators, such as incarceration rates, college attendance rates, fertility rates, and marriage patterns [93,94,95]. Having a better understanding of the mechanisms and processes that occur in poor neighborhoods, as well as the logics of the neighborhood effects and the interactions between them, can greatly improve the effectiveness of these actions in deprived areas.

Many researchers have tried to explain how neighborhoods affect the life chances of the residents. Small and Feldman [96] have suggested that studies of neighborhood effects are at a crossroads. On the one hand, many quantitative studies on neighborhood effects encounter the problem of selection bias [53]. In many cases, neighborhoods attract people with certain income levels. Thus, a neighborhood’s characteristics may be rather endogenous, which can lead to bias in the research results on these neighborhoods. On the other hand, the dominant research questions regarding neighborhood effects are focused on the measurement of the magnitude of those effects, rather than on trying to understand under what circumstances the effects matter. Small and Feldman [96] recommended conducting more ethnographic studies of neighborhoods, adding that such studies should be integrated into the quantitative empirical research agenda. Specifically, they argued that ethnographic studies could help to explain the contractionary results of previous neighborhood research. Thus, it appears that more qualitative insights are needed to fully explain the mechanisms of neighborhood effects.

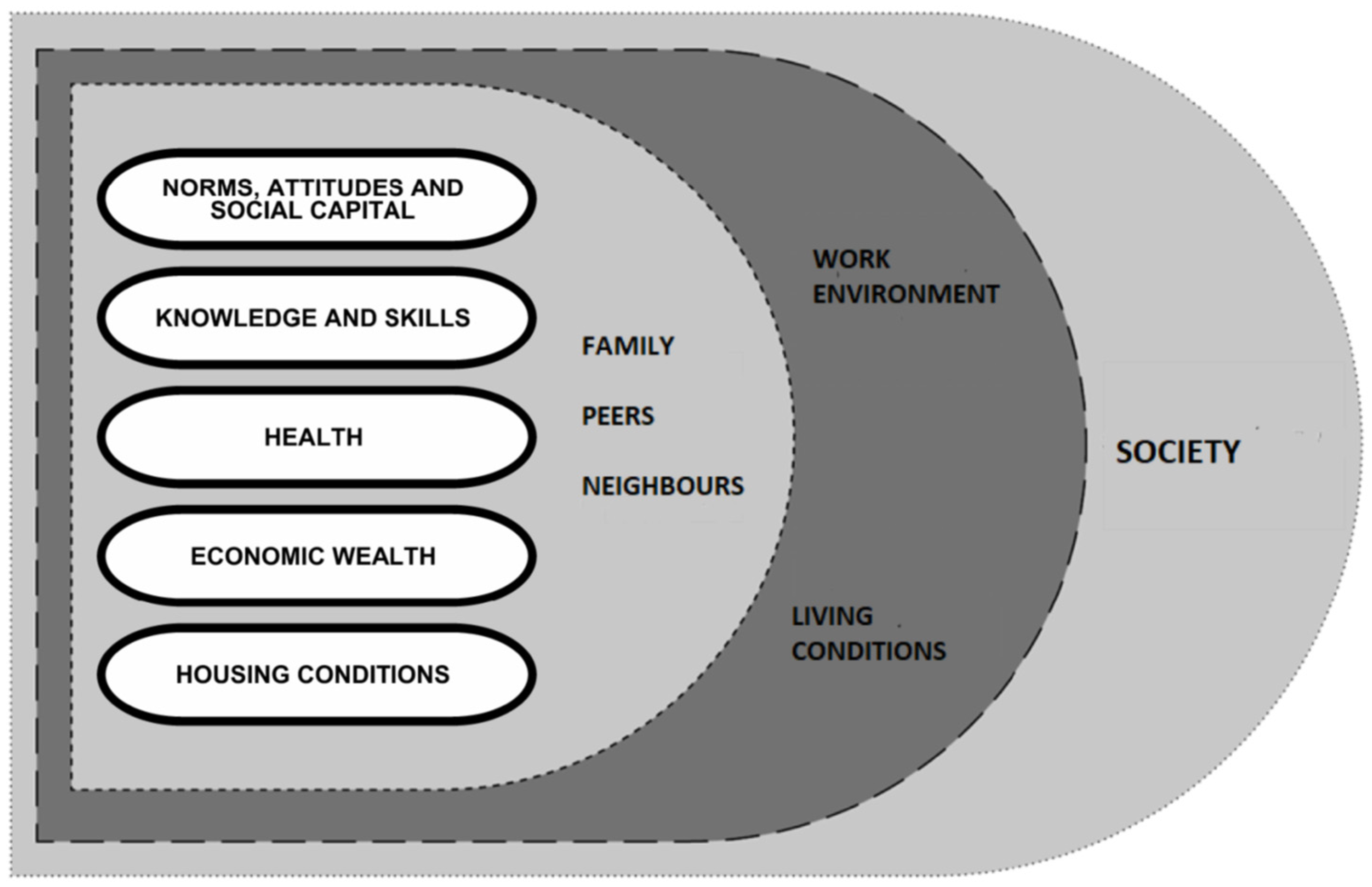

1.3. Poverty Enclaves in the Post–Industrial Context of Łódź

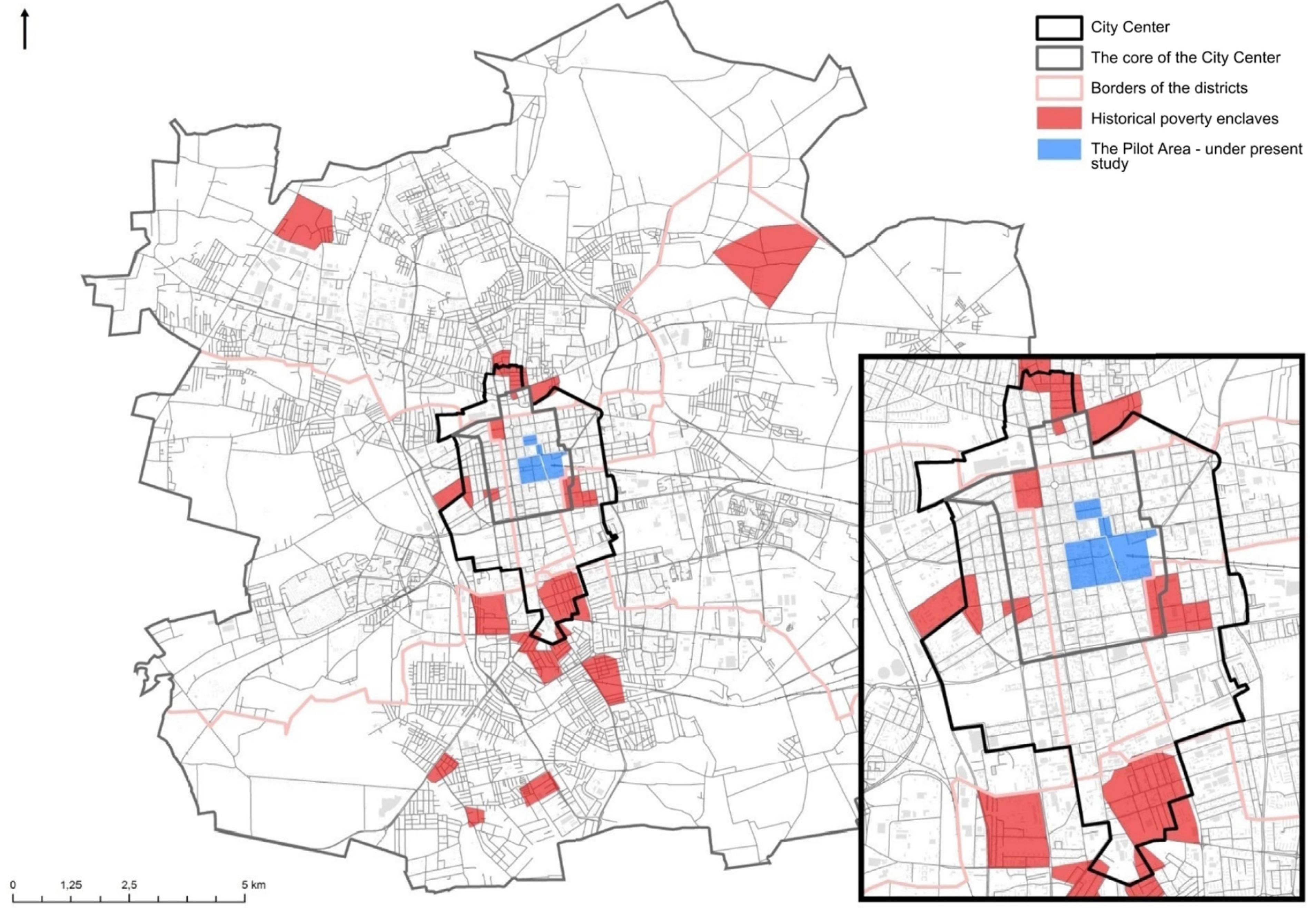

The analysis presented in this article was conducted in the context of a degraded area of the Łódź city center. In Łódź, the assessment of the inhabitants’ quality of life is clearly related to their place of residence, as the social composition of the different districts and housing estates of Łódź varies considerably. Over the last 25 years, three large studies on poverty in Łódź have been conducted. These three studies were as follows: “Urban poor. A new layer in the social structure”, which was implemented in the 1993–1996 period; “Forms of poverty and social threats and their distribution in Łódź”, which was performed in the 1996–1999 period; and “WZLOT—Strengthen the opportunities and weaken the transmission of poverty among the inhabitants of the cities of the Łódź Municipality”, which was undertaken in the 2008–2010 period [97,98]. In the third of these three projects, researchers re–interviewed a large proportion of the interviewees from 1996–1999, and were thus able to gain insights into the longer–term biographies of the residents and their families. As a result of these research activities, there is a large body of literature on poverty in Łódź. Most of these studies were qualitative research projects focused on capturing and describing the most dramatic phenomena related to poverty. The results of those projects indicated that in Łódź, poor people were not distributed equally across all parts of the city, but were instead primarily concentrated in Łódź city center. Moreover, they found that within the city center, the distribution of poor people as not even, as it was concentrated in so–called “poverty enclaves”. Attempts to locate these poverty enclaves on the map of the city were made in the framework of the 1996–1999 study. On the basis of statistical calculations, 17 areas covering at least two adjacent street quarters were identified in which one–third of the inhabitants were living in a household receiving social assistance. Of these 17 areas, 12 were in the broadly–defined downtown area, and four were on the outskirts of the city. In the course of these studies, researchers also observed that living in a poverty enclave particularly affected children, about half (48–55%) of whom came from families who were receiving social assistance (all persons aged 17 and under were considered children). The study conducted ten years later (in 2008–2010) confirmed the existence of all of the previously identified central enclaves of poverty, though the peripheral enclaves had disappeared. This study also identified 11 schools at which the percentage of children receiving benefits was much higher than the average for Łódź (13%), ranging from 24% to 52%. The districts of these schools contained all 12 of the central enclaves identified ten years previously. Distribution of poverty enclaves based on the available literature are presented in the Figure 2. These results prompted researchers to propose the thesis that the poverty enclaves in the city center of Łódź are likely to persist. This finding connects the micro perspective of individual quality of life in the poverty enclaves with the macro perspectives of long–term mechanisms of socio–economic and political development in Poland. In this context, the emergence and persistence of the poverty enclaves within the Łódź city center can be seen as a product of the political and economic transformation of Poland [8,9,10].

Figure 2.

Distribution of poverty enclaves based on the available literature. Source: own study.

However, the borders of these poverty enclaves should not be seen as immutable. First, it is important to keep in mind that the enclaves were selected on the basis of some general characteristics that describe the overall population of the entire quarter (actually, two). At least theoretically, the selected enclaves could contain smaller areas and/or buildings inhabited by richer people. Second, these poverty enclaves have been changing over time, with the 2008–2010 study mentioning that at least some of them had been partially gentrified. Third, there were other permanent areas of concentrated poverty within the city that were not mentioned in the three projects. For example, a study by Gulczyńska [99] showed that people of different statuses in areas that had a reputation for being “poor” or “problematic” may have been mixing. The area that was the subject of this study bordered some of the enclaves identified in previous projects (especially the so–called “Wysoka enclave”).

In the literature, the formation of poverty enclaves in the Łódź city center is explained primarily by two factors [97,98]. The first factor is the collapse of industrial plants at the beginning of the 1990s, which caused many inhabitants of Łódź to experience unemployment and rapid impoverishment. The second factor is the poor housing conditions in the older tenement houses occupying the central area of the city. These two factors overlapped, causing an outflow of people who had adapted to the new economic conditions, and an influx of impoverished people from the city center. Many members of the latter group had been living in blocks of flats with full sanitary facilities, but had fallen behind on their rent, and were threatened with eviction. In return for having their debts settled and an additional fee, these individuals exchanged their higher–quality flats for worse apartments in the older tenement houses. At the same time, the city began to turn these tenement houses into social flats, and to move people evicted from communal and private buildings into these flats. As the scale of the social problems associated with poverty grew and unrenovated buildings fell into further disrepair in these areas, more affluent people left these neighborhoods. The questions of whether this process (i.e., of poor people moving into the city center) is still taking place, and, if so, on what scale, have not been investigated. It certainly appears that some of these poverty enclaves have shrunk in recent years as a result of spontaneous gentrification processes or planned revitalization efforts, as at least some of the poor people in these neighborhoods had to change their place of residence as a result of these activities and/or processes. It is not known whether these people moved to other places within the city center, or to the periphery of the city. In addition, the questions of whether new poverty enclaves have arisen, whether the old poverty enclaves have been replenished, and whether these people have dispersed evenly across the city’s territory have yet to be answered.

To sum up, the aim in this paper is to identify the mechanisms shaping the individual quality of life in poor neighborhoods located in Łódź city center. So, it was decided to focus on the micro perspective of the life trajectories of inhabitants living on the analyzed area. However, also, the macro perspective of urban marginality is included by referring to two points. The first relates to urban marginality as a product of social–economic development that creates more general context of my study. The second deals with possible alternatives (solutions) for the state and the society to deal with urban marginality. These alternatives are considered in the context of the public policy directed to enhancing the quality of life on the analyzed area. In that way a reference to Wacquant’s [8,9,10] classification of possible reactions to urban marginality—improved programs of the welfare state and new social rights.

Following Small and Feldman [96], the deeper insight into the complexity of the mechanisms shaping QoL in the poor neighborhoods of Łódź city center will be provided in this paper. The capability approach will be applied, as this concept refers to people’s chances and opportunities to enjoy a good quality of life. To fully embrace the multidimensionality of the QoL, different life domains will be taken into account (as was proposed in the Report on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress) [19]. An attempt to identify the conversion factors will be made that influence the capabilities individuals can generate from commodities, and that therefore shape their real quality of life. Moreover, most public policy measures are focused on conversion factors as phenomena that can unlock an individual’s potential. In particular, the focus in this paper will be made on how the quality of life of the inhabitants of the analyzed areas can be improved, rather than on ways to enhance their social mobility. This approach was chosen in light of the context of the municipality of Łódź. First, the public policy focus of the city council of Łódź is on improving the quality of life in those deprived areas, rather than on implementing measures that would lead to the relocation of the inhabitants within the city’s territory. The rationale behind this approach is twofold. First, there is the scarcity of social housing owned by the city council that can be used to relocate the inhabitants outside of poor neighborhoods, and especially of good–quality real estate. Second, there is evidence indicating that while the concentration of poverty in Łodź has become a permanent phenomenon, the distribution of the impoverished population across the city’s territory has been fluid, rather than fixed [93,94]. A crucial goal of this paper is to provide precise public policy recommendations that can be applied in reality. All of the research aims outlined above demand the use of both qualitative and quantitative analytical approaches that take into account both the spatial distribution of the residents within the analyzed area, and the social and economic phenomena taking place within it. In other words, at the analytical level, the paper will follow the local spatial context.

2. Materials and Methods

The analysis presented in this paper is based on the pilot area of a deprived neighborhood in Łódź city center, which was designated as part of the revitalization process financed from various sources (mainly public financing from the European Funds). The pilot area consists of:

- Quarter 1 (Zone 1): the “Kamienna” quarter (Revolution Street 1905, Kilińskiego Street, Jaracza Street, Wschodnia Street);

- Quarter 2 (Zone 2): a part of the New Centre of Łódź (Narutowicza Street, Kilińskiego Street, Tuwima Street, Piotrkowska Street); and

- Quarter 3 (Zone 3): the so–called “Kilińskiego connector” (Kilińskiego Street from Jaracza Street to Narutowicza Street), and Zone 1 of the New Centre of Łódź (Narutowicza Street, Nowotargowa Street, Tuwima Street, Kilińskiego Street).

Also included in the pilot area are the tenement houses with frontages adjacent to the area boundaries outlined above. This area was identified by the municipality of Łódż as the most important and emblematic of the areas targeted for revitalization in the city, as the combination of social problems with technical, infrastructural, economic, and environmental disadvantages appeared to be the most acute in this area.

In the analysis, different data sources were used, including:

- Quantitative data—These data were gathered from the following public registries: the population register, the labor office register, social assistance records, police records, and the registers of the municipality of Łódź (the data were available at the building level). These quantitative data enabled us to calculate the basic demographic, economic, and general life situation indicators of the residents in the pilot area. The indicators included:

- ○

- age and gender population structure;

- ○

- share of the unemployed: total and long–term unemployed;

- ○

- share of persons living in families receiving social benefits (in total, receiving means–tested social assistance, receiving public care services, and receiving social benefits due to disability);

- ○

- share of children living in families who received benefits from social assistance (in total and receiving meals financed by social assistance);

- ○

- share of persons who had municipal housing arrears;

- ○

- technical conditions of the buildings; and

- ○

- number of police interventions, as well as drug crimes in each zone of the pilot area.

These data (except for the data from the police) were placed on the GIS maps of the pilot areas, which enabled us to create an illustration of the phenomena at the building level (Supplementary Materials).

The idea to create maps at building level is rooted in Charles Booth’s maps of London poverty [100], where the author classified the poverty in London. In this paper maps present the quantitative data on indicators reflecting poor quality of life at the analyzed area at the lowest possible level that enables to compare the gathered material with qualitative study.

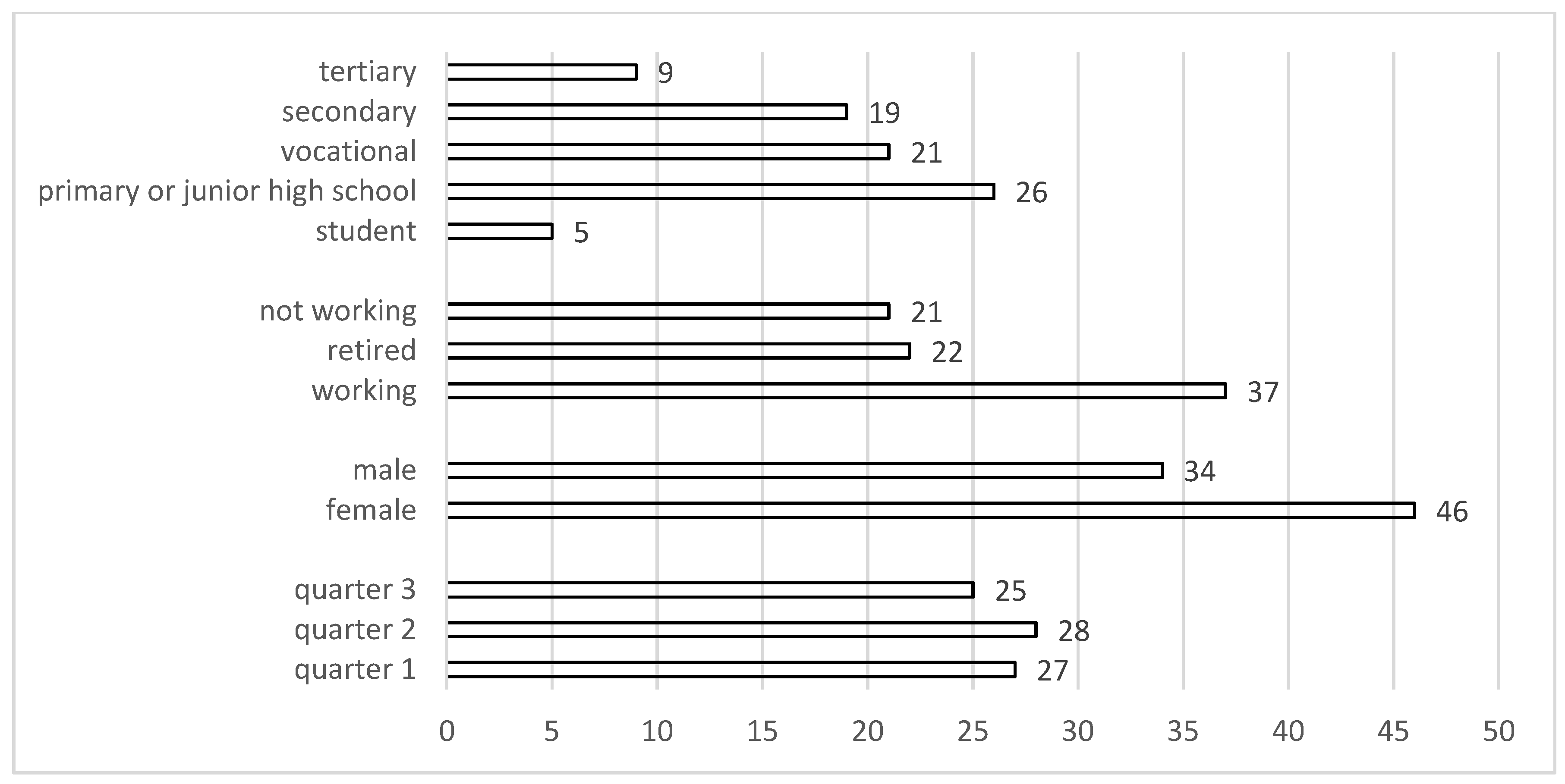

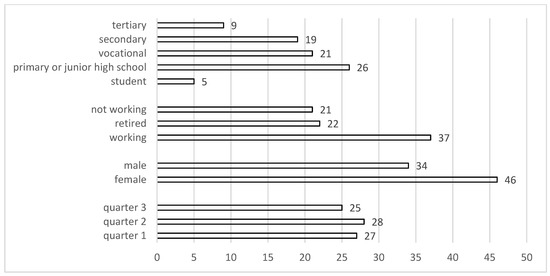

• Qualitative data—these are the primary data collected from in–depth interviews with residents of the pilot area, all of whom were socially excluded or at risk of exclusion, including municipal debtors. A total of 80 interviews were conducted between 14 May and 23 June 2015. The interviews lasted from 30 min to two hours, depending on the informational content of the interview and the respondent’s communicativeness (the interview time was clearly controlled by the moderator, not the respondent). Recruitment for the interviews was carried out using the random route method. Different starting addresses were used in each of the three examined quarters. As a result, the addresses of the respondents were scattered throughout the area covered by the study. Additionally, the snowball method was used to identify groups of respondents who tend to be more difficult to find (debtors, leaders). To recruit the homeless, street workers from the Municipal Social Welfare Centre and shelters for the homeless were consulted. The research process was smooth, as it was relatively easy to persuade the respondents to participate in the interviews, in part because they were remunerated for the time they spent in the interviews. The vast majority of the interviews took place at the respondents’ homes, which allowed for additional observations (e.g., about the technical condition of the apartment, and about the people who were living with the respondent). In line with the methodological assumptions, it aimed to have a sample of respondents that was composed of both even representations of the three pilot area quarters, and individuals with different demographic characteristics to ensure that the respondents’ stories, experiences, and opinions would be as diverse as possible. As a result, the interviewees were drawn from all three quarters of the pilot area. There were more female than male respondents, and the interviews were conducted with representatives of all age groups. While some of the respondents were working (including under specific contracts and mandates), others were not employed or were receiving a pension or retirement benefits. While the largest group of respondents had completed their education at the primary school level, significant shares also had vocational or secondary education (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Respondents’ structure by different dimensions, number of respondents in each category. Source: own study.

All interviews were recorded and transcribed. The ordered set of transcripts has been systematically coded, i.e., subjected to systematic analysis with the use of computer–assisted qualitative data analysis programs. About 2100 fragments of statements from the records of conversations with the residents were coded. Coding followed the classic Saladna [101] manual for qualitative data researchers, and was divided into two cycles. In the first (ordering) cycle, descriptive coding techniques were used, which allowed us to capture the most important topics raised by the respondents. This was an exploratory phase that was used to organize all the most important content emerging from the collected transcripts. The collected information covered almost all of the quality of life dimensions identified by the European Statistical System [18,19]. These dimensions are:

- material living conditions: especially the housing situation (condition of the apartment and tenement house) and material deprivation;

- productive or main activity: the situations of the respondents and their adult family members in the labor market or the work environment;

- health: the health status of all family members, disability, impact of health on the life situation, addictions;

- education: educational activities (limitations, plans);

- leisure and social interactions: relationships with other residents, ways of spending free time;

- economic and physical safety: relations with the police, sense of security;

- governance and basic rights: relations with public institutions; expectations/dreams/plans related to the transformation of Łódź;

- natural and living environment: history of living in the studied area, overall assessment of the neighborhood (positive and negative aspects); and

- overall experience of life: overall life satisfaction, satisfaction with the place of residence.

The above information on the quality of life dimensions was supplemented with detailed information on the residents’ family situations.

In the second coding cycle, the previously extracted contents were subjected to model coding, i.e., logical relationships between various elements of the respondents’ statements were searched for. Using this approach, it was able to describe the most important mechanisms underlying the problems in the studied area of Łódź. The adoption of such a procedure allowed us not only to organize our very extensive and multi–threaded research materials, but also to automate the analysis (e.g., to process quantitative information on coded fragments), which reduced the risk of a situation arising in which the analyses were based only on the subjective feelings and interpretations of the analyst. The software used to analyze the data was Maxqda.

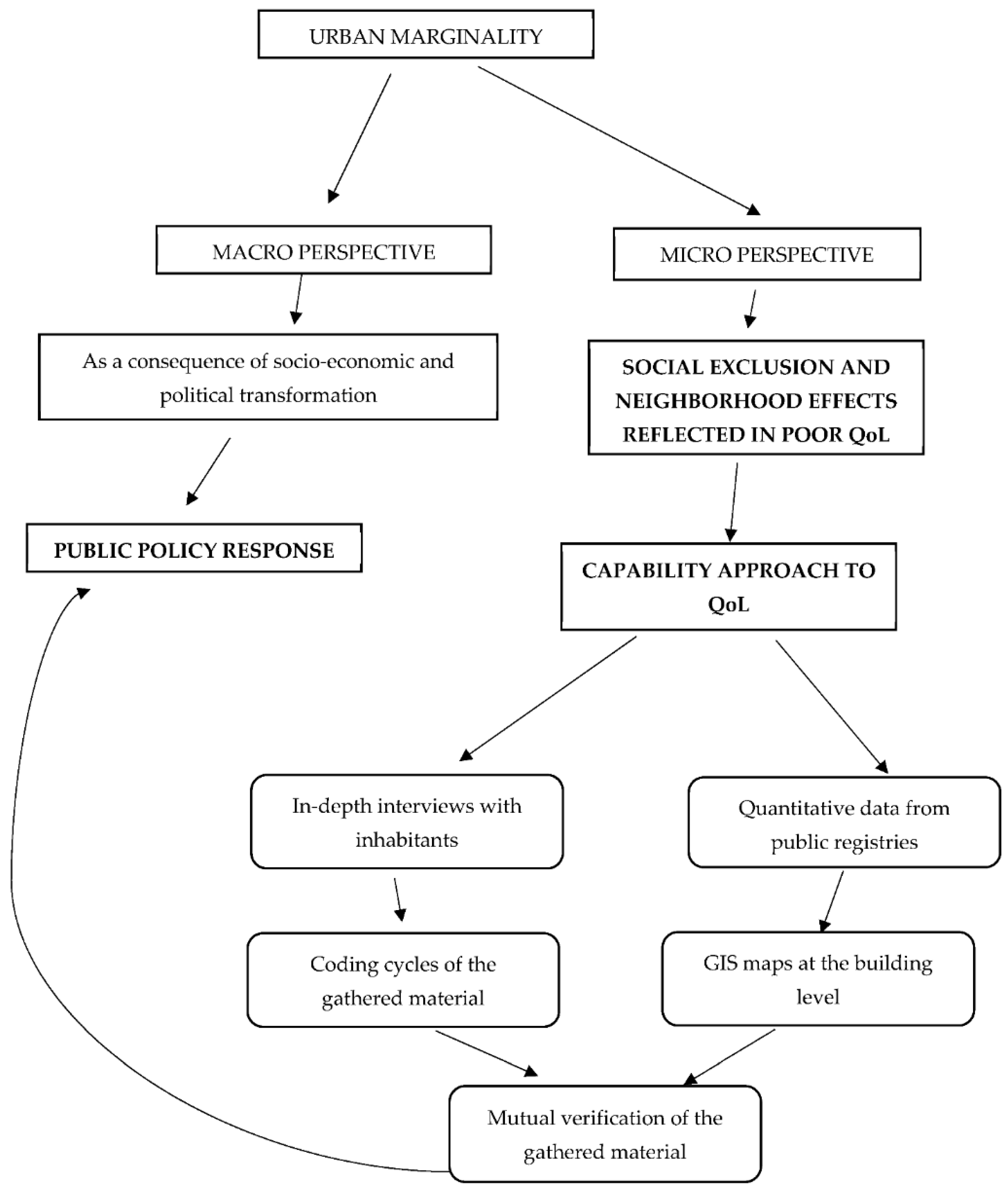

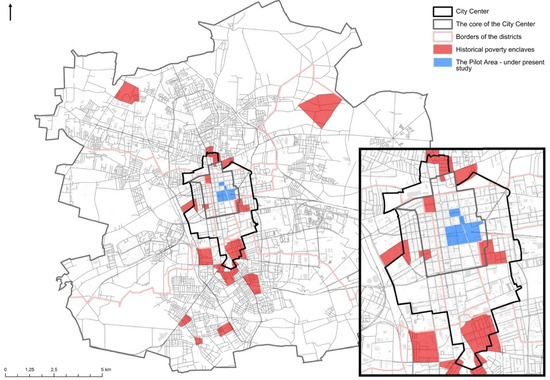

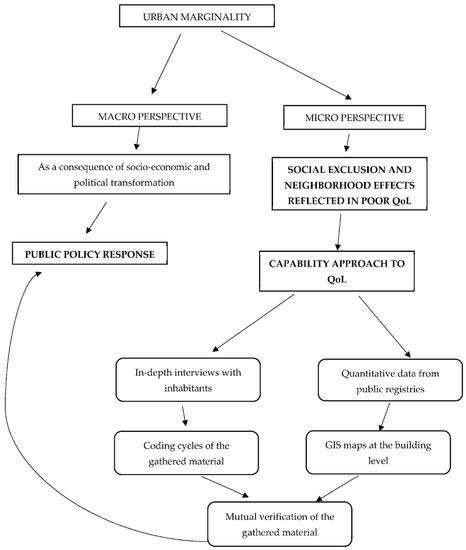

The overall research design encompassing the theoretical framework with data and methods is presented in the Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Research design. Source: own study.

3. Results

To systematically take into account the collected information (both qualitative and quantitative), and to identify the conversion factors in the complex contexts of the analyzed area, our first analytic step was to identify the individual life course trajectories of the respondents that led to particular life situations. Here, the individual life course is understood as a sequence of events leading to a particular life situation for the respondents and their families. Our approach is based on that of Dawid Lewis, who stated: “Any particular event that we might wish to explain stands at the end of a long and complicated causal history. We might imagine a world where causal histories are short and simple; but in the world as we know it, the only question is whether they are infinite or merely enormous” [102] (p. 214).

This observation is an insightful reflection on the realities of the social problems of the inhabitants of Łódź. When analyzing the stories of the respondents, the main conclusion was that there was no single mechanism underlying the social problems that emerged across various life situations. Of course, there were elements of specific mechanisms that appeared in many stories (mainly labor market problems, health problems, addictions), but the cause–and–effect sequence did not always follow the same logic.

This dynamic can be shown in two examples:

Respondent A:

Too low income in relation to the needs → increasing debt (rent, usurers) → bailiff proceedings → neurosis/depression → alcohol addiction

Respondent B:

Addiction to alcohol in youth → leaving education early → lower skills → problems with finding a job → long–term unemployment

Looking at these cases, we can see that addiction occurs in both. However, in one story, the addiction appears to have been a consequence of previous problems, arising as a result of an accumulation of situations that the person was unable to cope with. In the second case, the addiction was one of the main problems, and was followed by subsequent challenges that perpetuated the person’s disadvantaged position.

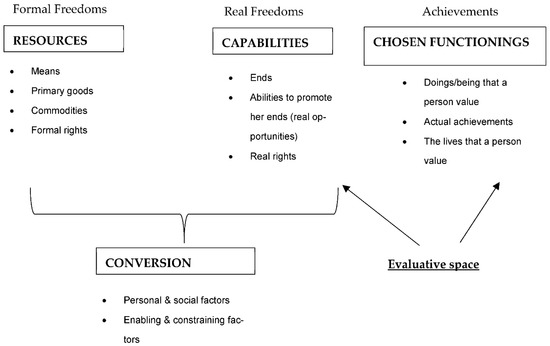

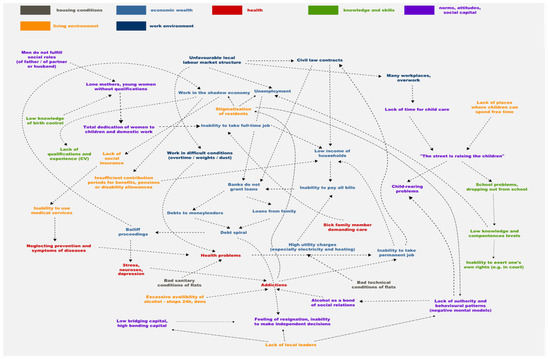

As a consequence, when analyzing the individual life trajectories of the 80 respondents, various mixtures of negative social phenomena were identified that could be seen as making up the “web of social exclusion” that entwined them, along many other coexisting and complicated mechanisms. A draft of such a web based on the interviews was developed in the first step, and was then verified with the quantitative data obtained from the registries. To create this web, maps at the building level were drawn up based on the quantitative data (Supplementary Materials). The final version of the web is presented in a synthetic way in the Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The web of social exclusion. Source: own study.

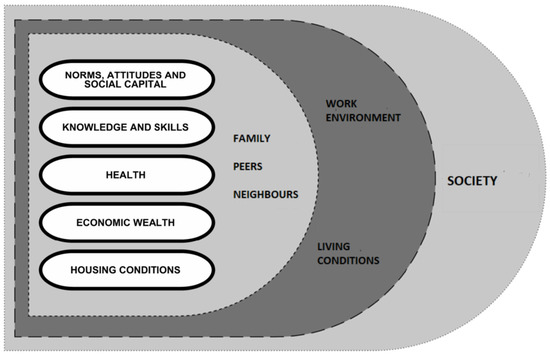

The web presents the conversion factors, as defined by Sen, that restricted the individuals from achieving their desired lifestyles. These factors can be grouped according to Sen’s individual, social, and environmental classifications. However, to better understand the complexity of the respondents’ situations, an alternative categorization of the conversions factors is proposed in this paper that is rooted in the identified mechanisms. The classification is presented in a simplified way in the figure below.

The proposed categorization of conversion factors (as depicted on the Figure 6) can be presented as a multi–level structure. The first level is “having a roof over your head”, and deals with housing conditions. The housing infrastructure in the pilot area is in poor condition. The most striking finding is the lack of flats with modern conveniences in quarters 1 and 3. In quarter 2, a small number of flats were equipped with a complete set of modern fittings. In areas 1 and 3, there were no flats equipped with a hot water system. Across the three quarters, the most common type of utility was gas. In the three surveyed quarters, most of the flats were also equipped with a flush toilet, although they were less likely to have a bathroom. Moreover, very few of the flats had central heating. Especially in quarters 1 and 3, the dwellings of the municipal housing stock did not provide decent living conditions. The poor condition of these dwellings had repercussions. As was indicated on the web, living in sub–standard housing conditions often caused health problems for the inhabitants. In particular, deficient sanitary conditions and mold growth frequently led the inhabitants to develop asthma and other lung diseases. In economic terms, the poor technical condition of the flats resulted in the residents having suspended utility bills due to outdated heating systems, using alternative home heating methods, or experiencing large heat losses due to leaky windows. Moreover, the poor technical condition of the buildings deepened the stigmatization of the residents, which, in turn, exacerbated their labor market challenges.

Figure 6.

Categorization of conversion factors in the pilot area in Łodź. Source: own study.

The second floor is economic wealth. This level covers income (in terms of both income level and sources), but also material deprivation. Many previous studies on the social problems in Łódź also found that the inhabitants had unfavorable financial situations, mainly due to the difficult structural conditions of the labor market caused by the city’s deindustrialization processes [97]. Most of the respondents had low incomes and relatively high levels of material deprivation, which made it very challenging for them to pay their bills or to meet their other financial obligations. Thus, many of the respondents were looking for opportunities to borrow money. However, due to their lack of credit worthiness, banks usually refused to grant them loans. Many of the respondents reported taking out loans from family members, or worse, from moneylenders, which led them into a spiral of debt that was difficult for them to break, and often ended with bailiff proceedings. Generally, the respondents’ low income levels were related to their bad labor market situations. Two main labor market situations were identified among the respondents. The first was related to the lack of work caused in part by economic factors, but above all by issues of structural mismatch and low competence levels. The second was related to working in the shadow economy with low remuneration levels and a lack of social insurance. Many of the mothers reported that they were unable to seek full–time employment because of their child care responsibilities.

The next level refers to health. The respondents talked about a very wide range of diseases that they, their families, or neighbors were struggling with, including eye diseases, problems with the respiratory system (usually asthma), movement limitations (paresis after strokes), diabetes, neoplastic diseases, several diseases of the nervous system (diffuse sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy), and dementia (including Alzheimer’s disease). The respondents displayed low levels of health awareness. Their health problems resulted in part from a lack of preventive health care, tough working conditions (working overtime), and poor housing conditions. Moreover, being in bad health decreased the respondents’ employability. In several interviews, the respondents clearly associated their own illness or the illness or death of a loved one with the start of a series of acute problems (including the emergence of debt). The main source of these health problems appeared to be the insufficient health awareness of the residents, with many respondents indicating that they did not check themselves prophylactically, and often neglected the symptoms of diseases (while sometimes hiding these symptoms from family members). However, this lower health care usage was related not only to the respondents’ lack of knowledge, but also to their professional and financial situations. Some of the residents said they were afraid to use health care as they were uncertain about their health insurance coverage. Other respondents reported that were concerned about taking time off of work because they were employed under a civil law contract, and thus had no formal right to sick leave. Thus, for respondents who were working on an hourly or piecework basis, spending time on medical procedures might have lowered their income. Within this level, the main issues were addictions (alcohol and drugs), which were often obstacles to getting a permanent job. Having an addiction tended to damage an individual’s cognitive capacities, which may, in turn, have harmed the person’s life situation. The other side effects of addictions included dissociating from life and high levels of stress and neurosis. However, the broad availability of alcohol and drugs, and the role alcohol played in social relations in the local community, may have slightly offset the negative effects of alcohol and drug use.

Knowledge and skills constitute the next level, which affected inhabitants of all ages. Here, knowledge and skills refer not only to professional skills and knowledge, but also to the knowledge and skills needed for daily functioning. Having a low level of education, being a school drop–out, or lacking formal work experience (due to work in the shadow economy) could make it difficult for the respondents to find a decent job, but also to exert their own rights (i.e., in court or other public institutions). Low levels of sexual awareness among teenagers and adolescents and lower levels of knowledge of birth control led in many cases to teenage pregnancy. Moreover, the education of children (both formal and informal) was a significant problem in the analyzed area. Due to their high living expenses and low parenting skill levels, the issue of “investing” in the development of their children (e.g., by purchasing additional, extracurricular books) was hardly mentioned by the respondents. Many of the descriptions of these problems in the interviews suggested that the respondents who talked about them were acting in a slightly automated manner, duplicating the behavioral models present in their neighborhood or in their family.

The next level covers norms and attitudes of the respondents and their families, but also of a broader circle of friends, relatives, and the local society. It also deals with social capital. A few core conclusions can be drawn here. The first is there was a lack of positive behavioral patterns and of local leaders or authorities. Thus, a tendency was observed among the respondents to consolidate unfavorable mental models. Negative phenomena that lasted a long time in a specific area of the city ceased to be just events, and instead became something that could be described as “the grammar of human behavior”. These phenomena created social models of values, attitudes, and behaviors that overlapped with the limitations of individuals and households, making it difficult for them to overcome problems. In some cases, a person rarely acts in an individualized, critical, reflective manner, and instead usually acts automatically, based on unconscious mental models in his or her head, i.e., [103]. This pattern was clearly observed among the respondents, as the durability of the socio–spatial systems in their neighborhoods strengthened the mechanisms that led to the exclusion of the people living there. These unfavorable mental models also resulted in many childrearing problems. This was reflected in the observation made by many of the respondents that “the street is raising children”. This negative situation was further reinforced by the parents’ low parenting skill levels and failure to spend enough time with their children. In many cases, the men were not fulfilling their responsibilities as parents or partners, which led to many children being raised by lone mothers, many of whom were young, low–skilled, and outside of the labor market. According to the respondents, family was a source of problems rather than a source of support. In the local society of the analyzed area, drinking alcohol was treated as a social bond, and was mentioned in almost all of the interviews. The tough life situations of the respondents and the difficulties they had in dealing with their problems often led to resignation or to the inability to make their own decisions. However, it was also found that there were strong social ties in the analyzed area. The dominant type of social capital was bonding capital. The respondents were less likely to demonstrate that they had bridging capital, i.e., a form of capital that makes it easier for people to establish, maintain, and take advantage of relationships for their own benefit within a wider environment, and thus beyond their narrowest circles of family members and neighbors, see also [104]. Thus, the respondents were creating very strong ties within their micro–community (e.g., residents of one street), and were ready to comply with the rules of this group. They were, however, far less able to create relationships in wider social groups. The consequences of this pattern included not only manifestations of aggressive behavior (e.g., attacks on people they did not know, who “are not from here”), but also difficulties in adapting to other groups, including, for example, employee groups. This mechanism was, in turn, reinforced by the stereotypes that were widespread in the city about the inhabitants of these areas.

The next level of conversion factors is created by the work environment and living conditions. Here, the working environment refers to the unfavorable structure of the local labor market. Employers were reluctant to hire inhabitants of the pilot area due to stigmatization and stereotypes. The jobs they were offered were usually characterized by hard and unhealthy working conditions. Moreover, the main legal form of employment was through civil law contracts, which tend to be unfavorable for manual workers due to the low levels of protection they provide. Many of the residents reported working in the shadow economy without any social protections. Because of the low wages associated with these jobs, many of the respondents reported having to take many jobs to make ends meet. The residents’ living conditions were linked to their access to public services and public spaces. Many of the residents had no access to public health care because they had been working in the shadow economy, and thus had paid no social insurance contributions, and had not registered with the labor office. Within this level, the respondents reported that there was a lack of places to spend free time, especially for children and youth. When we look at the spatial distribution of goods and services, we see that the availability of alcohol was excessive. In the pilot area, there were many shops open 24 h a day that offered full access to alcohol, and especially to low–quality alcohol.

The above findings on the conversion factors and the mechanisms leading to social exclusion and low quality of life were confronted with the individual satisfaction of respondents with the place of residents and the neighborhood. It is striking that the satisfaction in question was connected strongly with the attachment to the neighborhood. The respondents can be divided into two, almost equally numerous groups, one of which declares attachment to the area, while the other speaks of its lack of emotional ties to the place of residence. The group with strong attachment to the neighborhood was generally satisfied with the place of residence, it was hard for them to imagine the relocation form that area. They realized that their life situation was tough, however they treated it as a shared experience at the neighborhood. That led to better satisfaction with the place of residence. During the interviews, there was one statement often heard that “old trees should not be replanted”—the interlocutors would not want to change their place of residence, because in new neighborhoods they would not be able to create the kind of bonds that they have managed to build in their current place over the years. The second group of respondents, who felt less attached to the neighborhood, were dissatisfied with the place of residence and the neighborhood. A much greater amplitude of emotions was hidden behind these statements, which expressed not only the lack of rooting and attachment from the neighborhood, but even aversion towards it. So there were reports of imprisonment in the area, living in it only because of a lack of financial means to move. The reasons for these negative feelings towards the neighborhood were primarily related to the very low technical standard of buildings, as well as the accumulation of people in the neighborhood, whom our respondents considered to be pathological.

At the end the questions arise how the objective indicators (based on the quantitative data from public registries), in which the life quality of the analyzed area is being reflected, relates to the qualitative findings (see Supplementary Materials). The quantitative data confirmed very precisely the qualitative results. The share of the unemployed persons in the total productive age population was very high, especially in quarter 1. It exceeded for some buildings 35% or even 50%, and mostly unemployment has had a long–term character. Moreover, the share of persons receiving social assistance exceeds 50% or even 80% for some premises—particularly in quarter 1. There were some buildings in the analyzed area, where even five persons receiving disability pensions lived. The average indebtedness of residential premises was so large, that it was impossible to pay off. This is an explanation for the high share of eviction judgements in that area, with special focus on quarter 1. Also, the buildings and flats’ condition was poor, the building wear and tear was in many cases above 30%.

This web of social problems, created in this paper, illustrates the magnitudes and interdependencies of the different conversion factors that limited the life chances of the respondents. Our first main conclusion is that in these poor neighborhoods, the mechanisms that led to the unfavorable life situations of the residents were complicated, and that there were many mechanisms that were interacting with each other. Moreover, whereas these phenomena or factors could be the reasons for certain life situations, in other cases, they were the consequence of a course of events that led to particular life situations. Thus, to understand the situations of these individuals, we need a single, comprehensive framework that enables us to understand the processes that take place in such neighborhoods. The capability approach, and especially a combined analysis of conversion factors, provides such a framework.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

In this paper the attention was paid to the micro perspective of the poor neighborhoods referring to the individual quality of life of a pilot area in the center of Łódź. The social situations and the individual life course trajectories of the residents analyzed through the lenses of conversion factors from Sen’s capability approach. This enabled me to establish a more universal classification of the conversion factors that can be used to understand the mechanisms of social exclusion in deprived areas. The proposed analytical approach focuses on the factors that influence people’s desired lifestyles, mainly by inhibiting them. From a methodological point of view, this article has proposed a research design that could be applied at the individual level of the inhabitants of the analyzed area, but while taking into account their spatial distribution across buildings and yards. Such an approach has a wide range of potential applications with direct public policy implications, and is thus an important contribution of this paper. The public policy recommendations are seen here in macro perspective of societal and public reactions to urban marginality [8,9,10].

The main intention of the author was to grasp the complexity of the social phenomena caused by various social mechanisms. The crucial research finding in this paper is that the causality between different phenomena occurring in the analyzed area (the reasons and the results) followed very different patterns, resulted not only from the individual features of the inhabitants and the neighborhood effects, but also from historical factors and the consequences of the public policies implemented in the analyzed area and among its inhabitants. So, the present situation in the analyzed area can be seen also as a product of the socio–economic transformation of Poland (macro perspective). A particular factor can be both a cause and a result of some phenomenon. The magnitude and the scope of mechanisms that were observed in the analyzed areas enabled the author to draw the conclusion that the residents of the pilot area in Łódż city center were caught within a web of social exclusion that was very hard to leave. Kleinhaus et al. [81] described such residents as stayers rather than movers, who have opportunities for residential and social mobility. Moreover, Kleinhaus et al. [81] referred to the network of poverty, while emphasizing the complexity and the persistence of the phenomena connected to poverty. Whereas in this paper, a broader perspective was taken by covering the different life domains that lowered the QoL in the analyzed area, it has been argued that the established web of social exclusion can be seen as a broader extension of the network of poverty by, e.g., [81].

The core research contribution of this paper is that it provided a joint analysis covering three aspects: the QoL (1) in poor neighborhoods (2) of the post–industrial city center of the municipality of Łódź (3). So, based on the micro perspective of individual quality of life the results were aggregated to the macro perspective of the public policy response to urban marginality, considered within the socio–economic, political, and historical development process of the Łódż Municipality. Moreover, the analysis took into account the spatial distribution of the residents experiencing various, mostly negative social phenomena at the building level. In the literature, the spatial aspects of poverty concentration have mainly been used to trace the segregation patterns of individuals belonging to vulnerable groups, such as migrants [105,106], or to trace spatial changes in poverty concentration [107]. By contrast, in this paper, the author traced the concentration of persons (with particular individual characteristics) who were experiencing particular social phenomena within the city’s territory (at the building and the yard level) that shaped their QoL. Unlike many other studies [93,94,95], the focus here was on the quality of life improvements among the residents of the analyzed poor neighborhoods, rather than on their social mobility or poverty concentration.

4.1. Public Policy Implications

The classification of conversion factors proposed in the article also points to areas for public policy intervention, as these factors were viewed within the entire context of the complex social processes that were taking place in the analyzed area, which generated strong neighborhood effects. What is especially important and worth emphasizing is that many of the interviewees represented environments and people who were struggling with multi–level problems in which causes and consequences were intertwined with each other. Helping people in such situations—and, more broadly, helping to solve the problems of the entire community—must be done through comprehensive work with individuals and families. It even appears that in many cases, it would be necessary to lead such people and families “by the hand” to integrate various sources of help (e.g., help related to working with social assistance) [108]. Thus, as well as needing material assistance, these people may require continuous counselling and ongoing support in managing procedures. One–off actions are certainly not enough. Due to the scale of these problems and their loops, changes will take time. No immediate change can be expected, although in many cases (e.g., in activities aimed at children), the results could be noticed quickly. The combination of the classification of conversion factors and the individual life trajectories of the respondents precisely indicates the groups of activities from each area of classification that should be introduced. Below these policy recommendations are provided as an illustration of the application potential of the analysis proposed in the article.

Another urgent problem is the issue of improving the condition of the flats in these neighborhoods, which should be considered in terms of the requirements for an adequate standard of living. Moreover, the results of this research allow us to identify not only buildings in need of renovation, but also elements of the street furniture or the places that various groups of residents of the pilot area spend their free time.

Public interventions are needed in the area of health. One possible recommendation is to create a social clinic or a “district” clinic, which would provide a wide range of services for families and people affected by various forms of exclusion. In considering activities for improving the health of excluded people, it is worth following the principles of the so–called “settings–based approach” developed on the initiative of the World Health Organization [see also 108]. This approach is based on the belief that the health problems of a person or a family depend not only on the individual choices of these people, but are strongly conditioned by the environment in which the people live. In the context of Łódź, this approach should be applied primarily to two problems: namely, alcohol addiction and the lack of sexual awareness among young people (which results in many pregnancies among young mothers and pregnancies in unstable relationships). The settings–based activities should include not only activities in the field of sexual education for young people, but also activities that lead to changes in the ways young people spend their time in order to reduce the impact of environmental mechanisms and situations that contribute to risky and harmful behavior. For example, it may be useful to establish a club or cafe where young people can spend time and learn various socially desirable types of interpersonal relations. In the case of alcoholism, such a settings–based approach would primarily mean the city council taking active measures to radically limit the availability of alcohol in a given area (reducing the number of points available, limiting the number of points selling at night), activating the police and city guard to crack down on the illegal alcohol trade alcohol.

It is clear that many of the problems faced by the inhabitants of the studied areas stem from competency deficits. The socially excluded residents in the analyzed area are unable to even think about their abilities in terms of their competences and deficits that may affect their labor market participation. Therefore, it is necessary to undertake additional work with these people that enables them to better understand the modern mechanisms operating in the labor market. Moreover, considerable attention should be paid to the formal, informal, and social education of children. Local public institutions (e.g., schools/kindergartens) should be involved in such activities to the greatest possible extent. This would enable communities to carry out educational activities at a lower cost (e.g., using school buildings, libraries, and theatres during hours when standard or repertoire activities are not taking place there).

Activities in the area of norms, attitudes, and social capital require activities rooted in local communities, and in the identification of people who can act as local leaders. Values and attitudes play large roles in social integration processes. Therefore, it is especially important to undertake work with residents in this area by showing them other ways of thinking about reality, and of overcoming limitations. Actions in this area produce the fastest results if they are targeted at children and young people. However, we cannot ignore the group of adults who also require significant support in order to achieve more in–depth social integration. Three groups of adults seem particularly worthy of attention in the area under study. The first group is made up of single mothers and women who take care of sick family members, and who are thus heavily burdened with household and child care duties. Support for this group should enable women to become more actively involved in professional and social life. The second group, which is related to the first, is made up of young men who are fathers, or are about to become fathers. The interviews with the residents and the representatives of institutions helping residents showed that there were huge problems with the maturity levels of fathers, and of men in general, which hindered them from fulfilling their roles, especially those related to the care of children and pregnant partners. The third group that stands out in the study is made up of the elderly. In the interviews, the respondents often reported that there were tensions between the elderly and the younger residents, or they made statements suggesting that older people lock themselves in four walls, give up their active lives, or use their free time outside of the home.

Another challenge is to create an appropriate work environment, and above all to counteract the stigmatization of the inhabitants of this area among local employers, and to support the creation of good–quality jobs. One of the key problems diagnosed in the examined neighborhoods of the city was the difficult professional situations of the inhabitants. Providing support in this area is a challenge because many of the respondents pointed to various reasons for being unemployed. However, the group that is most at risk of exclusion from the labor market is made up of women taking care of children (and, to a lesser extent, of women caring for sick family members). Public interventions should be based on the willingness of local entrepreneurs to participate in social changes in the studied area. The solutions can be sought in the fields of social and social economy in which private activists, innovators, and leaders conduct activities that generate income. But in this context, the aim would be less to accumulate capital than to achieve socially important goals. An example of such activities may be social cooperatives.

Yet another major challenge is shaping the living environment, including ensuring the availability of various types of public services within walking distance and places to spend free time, including in the form of small architecture. The inhabitants of the studied area did not complain about physical access to services (e.g., no schools or kindergartens in the area). However, in the interviews, especially with people suffering from debt, it became clear that for many people, finding their way through the thicket of bureaucratic procedures, regulations, and mechanisms can be daunting. Therefore, it is worth considering creating legal advice points for people in need in the analyzed areas, and providing employees of public institutions with additional training to improve the standards of the services they provide to people with problems, who may require much more attention on the part of the official than the “average” client coming into the office.

The area under study is now undergoing the complex revitalization process. However, it is still too soon to detect long–term results in terms of the social change. The author wishes to conduct the second wave of the analysis—within ten years after the first wave (round) of the study.

4.2. Limitations

The basic limitation of the study is that the analysis is done for a small area only, i.e., a part of the deprived city center of Łódź. Extending such an analysis across different contexts (countries and cities) is crucial, as doing so would help to establish the common characteristics of conversion factors across different contexts, as well as the interdependencies between them. This would provide a sound basis for quantitative model analysis. Our future research plans include the analysis of conversion factors across different contexts, first by researching other Polish cities and towns with deprived areas, and by assessing the effects of public policy measures on those areas.

Supplementary Materials

The following Supplementary Materials are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su13137185/s1.

Funding

The research was conducted under the public tender of the Łódź Municipality within the project: “Development of a model for revitalizing urban areas in a selected area in the city of Łódź”, financed under the European Funds from the Operational Program Technical Assistance 2014–2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to the fact the study was based on the in–depth interviews on the life situation of respondents. Respondents took part in the research voluntarily. All interviews were anonymized, the respondents were informed about it and they made an informed consent on that.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The paper is based on in–depth interviews and data from public registries of the Łódź Municipality. All data and the research report are available on public repository at http://rewitalizacja.centrumwiedzy.org (accessed on 1 May 2020).

Acknowledgments

The author wants to thank Paweł Śliwowski for valuable advice and inspiration for writing this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Sen, A. Equality of What? In Tanner Lectures on Human Values; McMurrin, S.M., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Choice, Welfare and Measurement; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Commodities and Capabilities; North–Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Social Exclusion: Concept, Applications, and Scrutiny; Social Development Papers No. 1; Asian Development Bank: Tokyo, Japan, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. The idea of justice. Philos. Soc. Crit. 2015, 41, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baffoe, G. Understanding the Neighborhood Concept and its Evolution. Environ. Urban. Asia 2019, 10, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spain, D.; Logan, J.R.; Molotch, H.L. Urban Fortunes: The Political Economy of Place. Soc. Forces 1988, 66, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wacquant, L. Urban Marginality in the Coming Millennium. Urban Stud. 1999, 36, 1639–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacquant, L. Revisiting territories of relegation: Class, ethnicity and state in the making of advanced marginality. Urban Stud. 2016, 53, 1077–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacquant, L. Territorial Stigmatization in the Age of Advanced Marginality. Thesis Eleven 2007, 91, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kährik, A. Tackling social exclusion in European neighbourhoods: Experiences and lessons from the NEHOM project. GeoJournal. 2006, 67, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D. Quality of Life: Concept, Policy and Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schalock, R.L.; Keith, K.D.; Verdugo, M.Á.; Gómez, L.E. Quality of Life Model Development and Use in the Field of Intel-lectual Disability in Understanding and Investigating Response Processes in Validation Research. 2010. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/225939030_Quality_of_Life_Model_Development_and_Use_in_the_Field_of_Intellectual_Disability (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Cummins, R. Moving from the quality of life concept to a theory. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2005, 49, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felce, D. Defining and applying the concept of quality of life. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 1997, 41, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, R.; Brown, I.; Nagler, M.E. Quality of Life in Health Promotion and Rehabilitation: Conceptual Approaches Issues and Applications; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Measuring Quality of Life; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat; Sponsorship Group on Measuring Progress. Well–Being and Sustainable Development: Final Report Adopted by the European Statistical System Committee. 2011. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/7330775/7339383/SpG–Final–report–Progress–wellbeing–and–sustainable–deve/428899a4–9b8d–450c–a511–ae7ae35587cb (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Eurostat. Final Report of the Expert Group on Quality of Life Indicators. 2016. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products–statistical–reports/–/KS–FT–17–004 (accessed on 16 August 2020).

- Berger-Schmitt, R.; Noll, H.-H. Conceptual Framework and Structure of a European System of Social Indicators; EuReporting Working Paper No. 9; Centre for Survey Research and Methodology (ZUMA): Mannheim, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J.E.; Sen, A.; Fitoussi, J.-P. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. 2009. Available online: https://www.stiglitz–sen–fitoussi.fr (accessed on 20 May 2020).

- Sen, A. Well–Being, Agency and Freedom the Dewey Lectures 1984. J. Philos. 1985, 82, 169–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. The Standard of Living; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Alkire, S. Valuing Freedom: Sen’s Capability Approach and Poverty Reduction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Robeyns, I. The Capability Approach: An Interdisciplinary Introduction; University of Amsterdam, Department of Political Science and Amsterdam School of Social Sciences Research: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Robeyns, I. The Capability Approach: A theoretical survey. J. Hum. Dev. 2005, 6, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuklys, W. Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach: Theoretical Insights and Empirical Applications; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Comim, F.; Qizilbash, M.; Alkire, S. (Eds.) The Capability Approach. Concepts, Measures and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schokkaert, E. The Capabilities Approach. In The Handbook of Rational and Social Choice; Anand, P., Pattanaik, P., Puppe, C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 542–566. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, K.; Lopez-Calva, L.F. Functionings and Capabilities. In Handbook of Social Choice and Welfare 2; Arrow, K.J., Sen, A., Suzumura, K., Eds.; Elsevier, North–Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 153–187. [Google Scholar]