The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in Supporting Second-Order Social Capital and Sustainable Innovation Ambidexterity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

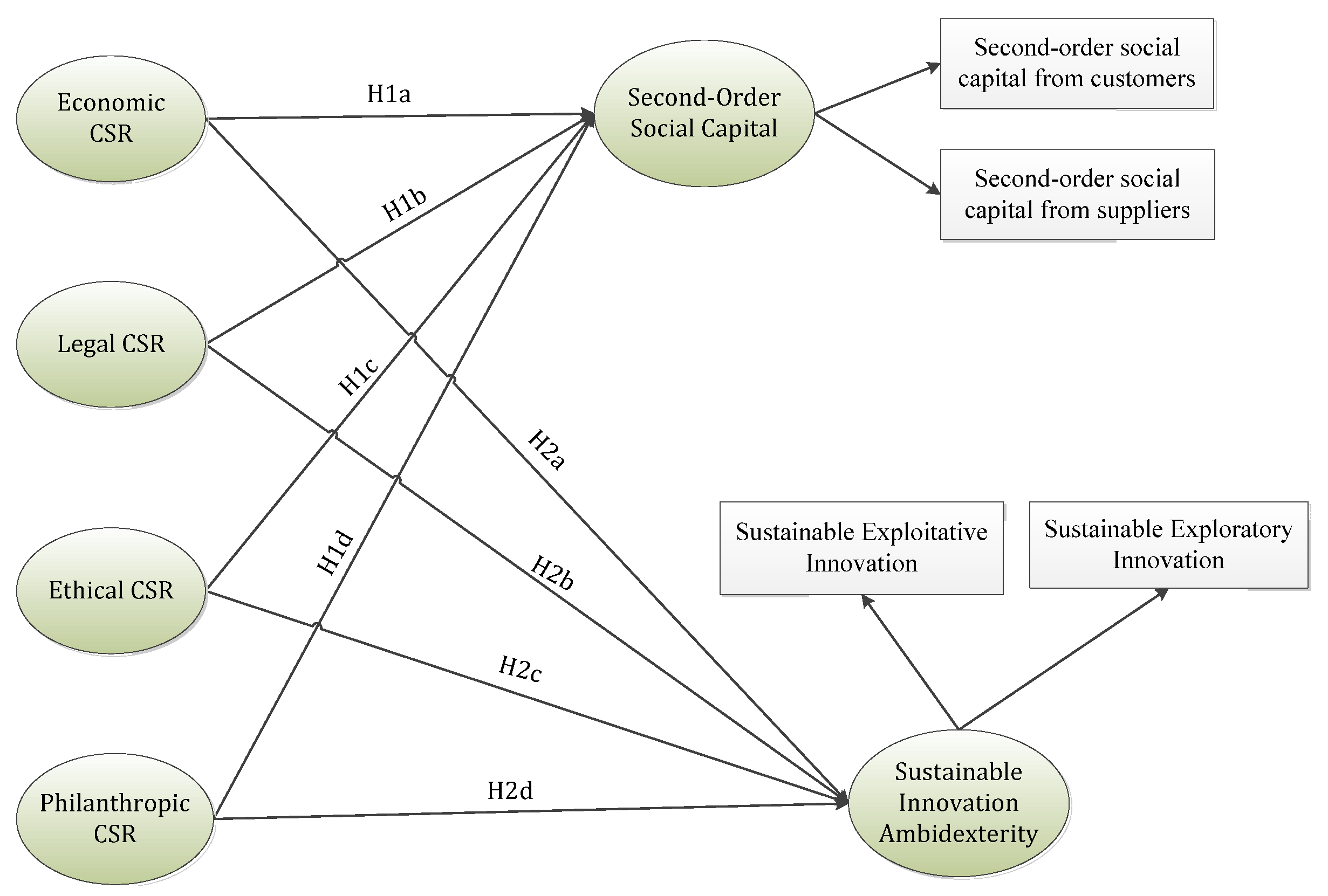

2.1. Corporate Social Responsibility and Second-Order Social Capital

2.2. Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainable Innovation Ambidexterity

3. Methodology

Sample and Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Data Analysis

4.2. Convergent and Discriminant Validity

4.3. Empirical Results

5. Discussion and Conclusions

6. Theoretical Implications

7. Practical Implications

8. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rajak, D. “Uplift and empower”: The market, morality and corporate responsibility on South Africa’s platinum belt. In Hidden Hands in the Market: Ethnographies of Fair Trade, Ethical Consumption, and Corporate Social Responsibility; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bielak, D.; Bonini, S.M.; Oppenheim, J.M. CEOs on strategy and social issues. McKinsey Q. 2007, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, J.P.S.-I.; Yañez-Araque, B.; Moreno-García, J. Moderating effect of firm size on the influence of corporate social responsibility in the economic performance of micro-, small-and medium-sized enterprises. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 151, 119774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A.; Shumate, M.; Meister, M. Walk the line: Active moms define corporate social responsibility. Public Relat. Rev. 2008, 34, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Yin, X.; Lee, G. The effect of CSR on corporate image, customer citizenship behaviors, and customers’ long-term relationship orientation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, S.; Rehman, S.U.; García, F.J.S. Corporate social responsibility and environmental performance: The mediating role of environmental strategy and green innovation. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 160, 120262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazalin, N.; Baydauletov, M. Corporate social responsibility strategy and corporate environmental and social performance: The moderating role of board gender diversity. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1664–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Seo, K.; Sharma, A. Corporate social responsibility and firm performance in the airline industry: The moderating role of oil prices. Tour. Manag. 2013, 38, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Song, H.; Lee, C.-K.; Lee, J.Y. The impact of four CSR dimensions on a gaming company’s image and customers’ revisit intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 61, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The four faces of corporate citizenship. Bus. Soc. Rev. 1998, 100, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesar, S.; Jhony, O. Corporate Social Responsibility supports the construction of a strong social capital in the mining context: Evidence from Peru. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 122162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. The Forms of Capital. (1986). In Cultural Theory: An Anthology; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Belliveau, M.A.; O’Reilly, C.A., III; Wade, J.B. Social capital at the top: Effects of social similarity and status on CEO compensation. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 1568–1593. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, R.S. The contingent value of social capital. Adm. Sci. Q. 1997, 42, 339–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollenbeck, J.R.; Jamieson, B.B. Human capital, social capital, and social network analysis: Implications for strategic human resource management. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 29, 370–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methot, J.R.; Rosado-Solomon, E.H.; Allen, D.G. The network architecture of human captial: A relational identity perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2018, 43, 723–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coleman, J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, R.; Johnston, A.; Thompson, P. Network capital, social capital and knowledge flow: How the nature of inter-organizational networks impacts on innovation. Ind. Innov. 2012, 19, 203–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Guan, J. Social capital, exploitative and exploratory innovations: The mediating roles of ego-network dynamics. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 126, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galunic, C.; Ertug, G.; Gargiulo, M. The positive externalities of social capital: Benefiting from senior brokers. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 1213–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Feng, T.; Shi, H. External involvement and green product innovation: The moderating role of environmental uncertainty. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1167–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, P.; O’Toole, T.; Biemans, W. Measuring involvement of a network of customers in NPD. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2016, 33, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, W.; Feng, T. Does second-order social capital matter to green innovation? The moderating role of governance ambidexterity. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 25, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavassoli, M.; Saen, R.F. Predicting group membership of sustainable suppliers via data envelopment analysis and discriminant analysis. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 18, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.; Kratzer, J. Social entrepreneurship, social networks and social value creation: A quantitative analysis among social entrepreneurs. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2013, 5, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, S.; Choi, T.Y.; Hur, D. Buyer power and supplier relationship commitment: A cognitive evaluation theory perspective. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2017, 53, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzner, B.; Wagner, M. Green Innovation and Profitability: The Moderating Effect of Environmental Uncertainty. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2019, 2019, 12337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Chen, C.-C.; Lu, K.-H.; Wibowo, A.; Chen, S.-C.; Ruangkanjanases, A. Supply Chain Ambidexterity and Green SCM: Moderating Role of Network Capabilities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Guan, J. Policy and innovation: Nanoenergy technology in the USA and China. Energy Policy 2016, 91, 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Cantor, D.E.; Montabon, F.L. How environmental management competitive pressure affects a focal firm’s environmental innovation activities: A green supply chain perspective. J. Bus. Logist. 2015, 36, 242–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragu, I.-M.; Tiron-Tudor, A. Integrating best reporting practices for enhancing corporate social responsibility. In Corporate Social Responsibility in the Global Business World; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 27–47. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Windsor, D. Corporate Social Responsibility: A Theory of the Firm Perspective: Some Comments. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 502–504. [Google Scholar]

- Idowu, S.O.; Dragu, I.-M.; Tiron-Tudor, A.; Farcas, T.V. From CSR and sustainability to integrated reporting. Int. J. Soc. Entrep. Innov. 2016, 4, 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. The network structure of social capital. Res. Organ. Behav. 2000, 22, 345–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Liang, C.; Gu, D. Mobile social media use and trailing parents’ life satisfaction: Social capital and social integration perspective. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2021, 92, 383–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, M.A.; Ghosh, S.; Hora, M. The influence of supply network structure on firm innovation. J. Oper. Manag. 2014, 32, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vveinhardt, J.; Andriukaitiene, R.; Cunha, L.M. Social capital as a cause and consequence of corporate social responsibility. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2014, 13, 483–505. [Google Scholar]

- Weisband, E. The virtues of virtue: Social capital, network governance, and corporate social responsibility. Am. Behav. Sci. 2009, 52, 905–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degli Antoni, G.; Portale, E. The effect of corporate social responsibility on social capital creation in social cooperatives. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2011, 40, 566–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melay, I.; Kraus, S. Green entrepreneurship: Definitions of related concepts. Int. J. Strateg. Manag 2012, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Pekovic, S.; Vogt, S. The fit between corporate social responsibility and corporate governance: The impact on a firm’s financial performance. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2020, 15, 1095–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; Chen, F.; Jones, P.; Xia, S. The effect of institutional investors’ distraction on firms’ corporate social responsibility engagement: Evidence from China. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J. Drivers of corporate social responsibility: The role of formal strategic planning and firm culture. Br. J. Manag. 2010, 21, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallaster, C.; Kraus, S.; Kailer, N.; Baldwin, B. Responsible entrepreneurship: Outlining the contingencies. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 538–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melay, I.; O’Dwyer, M.; Kraus, S.; Gast, J. Green entrepreneurship in SMEs: A configuration approach. Int. J. Entrep. Ventur. 2017, 9, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliams, A.; Siegel, D. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Correlation or misspecification? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L. Corporate social responsibility, the atmospheric environment, and technological innovation investment. Sustainability 2019, 11, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Javeed, S.A.; Latief, R.; Jiang, T.; San Ong, T.; Tang, Y. How environmental regulations and corporate social responsibility affect the firm innovation with the moderating role of Chief executive officer (CEO) power and ownership concentration? J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 308, 127212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Qu, Y.; Javed, S.A.; Zafar, A.U.; Rehman, S.U. Relation of environment sustainability to CSR and green innovation: A case of Pakistani manufacturing industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.L.; Rhou, Y.; Uysal, M.; Kwon, N. An examination of the links between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and its internal consequences. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 61, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petter, S.; Straub, D.; Rai, A. Specifying formative constructs in information systems research. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 623–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y.; Phillips, L.W. Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Adm. Sci. Q. 1991, 36, 421–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tenenhaus, M.; Vinzi, V.E.; Chatelin, Y.-M.; Lauro, C. PLS path modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2005, 48, 159–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzels, M.; Odekerken-Schröder, G.; Van Oppen, C. Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Q. 2009, 33, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Anthony, E.L.; Daniels, S.R.; Hall, A.V. Social exchange theory: A critical review with theoretical remedies. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2017, 11, 479–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, K.K.; Ryoo, S.Y.; Jung, M.D. Inter-organizational information systems visibility in buyer–supplier relationships: The case of telecommunication equipment component manufacturing industry. Omega 2011, 39, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferasso, M.; Beliaeva, T.; Kraus, S.; Clauss, T.; Ribeiro-Soriano, D. Circular economy business models: The state of research and avenues ahead. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 3006–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Item Code | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic CSR | Eco1 | 0.742 | 0.864 | 0.865 | 0.615 |

| Eco2 | 0.789 | ||||

| Eco3 | 0.789 | ||||

| Eco4 | 0.815 | ||||

| Legal CSR | Leg1 | 0.813 | 0.796 | 0.797 | 0.569 |

| Leg2 | 0.770 | ||||

| Leg3 | 0.673 | ||||

| Ethical CSR | Ethi1 | 0.696 | 0.825 | 0.821 | 0.607 |

| Ethi2 | 0.778 | ||||

| Ethi3 | 0.855 | ||||

| Philanthropical CSR | Phi1 | 0.803 | 0.802 | 0.801 | 0.575 |

| Phi2 | 0.790 | ||||

| Phi3 | 0.675 | ||||

| SEP (Sustainable Exploratory Innovation) | SEP1 | 0.794 | 0.925 | 0.924 | 0.671 |

| SEP2 | 0.755 | ||||

| SEP3 | 0.766 | ||||

| SEP4 | 0.802 | ||||

| SEP5 | 0.809 | ||||

| SEP6 | 0.800 | ||||

| SET (Sustainable Exploitative Innovation) | SET1 | 0.769 | 0.892 | 0.892 | 0.623 |

| SET2 | 0.782 | ||||

| SET3 | 0.759 | ||||

| SET4 | 0.779 | ||||

| SET5 | 0.787 | ||||

| SOCC (Second-order Social Capital from Customers) | SOCC1 | 0.699 | 0.905 | 0.906 | 0.548 |

| SOCC2 | 0.743 | ||||

| SOCC3 | 0.741 | ||||

| SOCC4 | 0.763 | ||||

| SOCC5 | 0.778 | ||||

| SOCC6 | 0.745 | ||||

| SOCC7 | 0.657 | ||||

| SOCC8 | 0.651 | ||||

| SOSS (Second-order Social Capital from Suppliers) | SOSS1 | 0.720 | 0.822 | 0.824 | 0.610 |

| SOSS2 | 0.779 | ||||

| SOSS3 | 0.800 |

| Construct | Item Code | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainable Innovation Ambidexterity (Second Order) | SEP | 0.819 | 0.945 | 0.945 | 0.612 |

| SET | 0.790 | ||||

| Second-order Social Capital (Second Order) | SOCC | 0.740 | 0.928 | 0.919 | 0.541 |

| SOSS | 0.780 |

| ECO | ETHI | LEG | PHI | GEP | GET | SOCC | SOSC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eco1 | 0.742 | 0.499 | 0.697 | 0.756 | 0.454 | 0.596 | 0.790 | 0.593 |

| Eco2 | 0.789 | 0.556 | 0.766 | 0.753 | 0.526 | 0.577 | 0.850 | 0.633 |

| Eco3 | 0.789 | 0.631 | 0.733 | 0.718 | 0.501 | 0.550 | 0.847 | 0.691 |

| Eco4 | 0.815 | 0.657 | 0.810 | 0.739 | 0.491 | 0.566 | 0.879 | 0.692 |

| Ethi1 | 0.535 | 0.696 | 0.613 | 0.606 | 0.430 | 0.391 | 0.677 | 0.765 |

| Ethi2 | 0.554 | 0.778 | 0.715 | 0.713 | 0.507 | 0.431 | 0.688 | 0.903 |

| Ethi3 | 0.655 | 0.855 | 0.645 | 0.773 | 0.687 | 0.579 | 0.681 | 0.960 |

| Leg1 | 0.833 | 0.668 | 0.813 | 0.717 | 0.529 | 0.557 | 0.897 | 0.705 |

| Leg2 | 0.741 | 0.614 | 0.770 | 0.762 | 0.484 | 0.563 | 0.832 | 0.674 |

| Leg3 | 0.579 | 0.628 | 0.673 | 0.589 | 0.436 | 0.471 | 0.730 | 0.641 |

| Phi1 | 0.733 | 0.771 | 0.733 | 0.803 | 0.593 | 0.562 | 0.758 | 0.973 |

| Phi2 | 0.800 | 0.647 | 0.741 | 0.790 | 0.612 | 0.732 | 0.776 | 0.718 |

| Phi3 | 0.606 | 0.623 | 0.604 | 0.675 | 0.590 | 0.583 | 0.629 | 0.661 |

| SEP1 | 0.553 | 0.605 | 0.504 | 0.661 | 0.835 | 0.755 | 0.556 | 0.620 |

| SEP2 | 0.454 | 0.545 | 0.508 | 0.603 | 0.909 | 0.707 | 0.485 | 0.605 |

| SEP3 | 0.510 | 0.534 | 0.554 | 0.606 | 0.877 | 0.700 | 0.539 | 0.573 |

| SEP4 | 0.513 | 0.628 | 0.533 | 0.655 | 0.893 | 0.710 | 0.545 | 0.669 |

| SEP5 | 0.529 | 0.587 | 0.535 | 0.683 | 0.899 | 0.737 | 0.544 | 0.665 |

| SEP6 | 0.528 | 0.556 | 0.524 | 0.657 | 0.905 | 0.778 | 0.533 | 0.624 |

| SET1 | 0.522 | 0.499 | 0.582 | 0.633 | 0.705 | 0.876 | 0.555 | 0.551 |

| SET2 | 0.559 | 0.480 | 0.554 | 0.636 | 0.734 | 0.930 | 0.558 | 0.532 |

| SET3 | 0.510 | 0.468 | 0.546 | 0.616 | 0.753 | 0.895 | 0.528 | 0.515 |

| SET4 | 0.668 | 0.443 | 0.545 | 0.679 | 0.659 | 0.857 | 0.612 | 0.524 |

| SET5 | 0.616 | 0.501 | 0.557 | 0.693 | 0.676 | 0.868 | 0.604 | 0.537 |

| SOCC1 | 0.873 | 0.499 | 0.697 | 0.756 | 0.454 | 0.596 | 0.790 | 0.593 |

| SOCC2 | 0.924 | 0.556 | 0.766 | 0.753 | 0.526 | 0.577 | 0.850 | 0.633 |

| SOCC3 | 0.911 | 0.631 | 0.733 | 0.718 | 0.501 | 0.550 | 0.847 | 0.691 |

| SOCC4 | 0.916 | 0.657 | 0.810 | 0.739 | 0.491 | 0.566 | 0.879 | 0.692 |

| SOCC5 | 0.833 | 0.668 | 0.962 | 0.717 | 0.529 | 0.557 | 0.897 | 0.705 |

| SOCC6 | 0.741 | 0.614 | 0.957 | 0.762 | 0.484 | 0.563 | 0.832 | 0.674 |

| SOCC7 | 0.579 | 0.628 | 0.900 | 0.589 | 0.436 | 0.471 | 0.730 | 0.641 |

| SOCC8 | 0.535 | 0.949 | 0.613 | 0.606 | 0.430 | 0.391 | 0.677 | 0.765 |

| SOSS1 | 0.554 | 0.976 | 0.715 | 0.713 | 0.507 | 0.431 | 0.688 | 0.903 |

| SOSS2 | 0.655 | 0.909 | 0.645 | 0.773 | 0.687 | 0.579 | 0.681 | 0.960 |

| SOSS3 | 0.733 | 0.771 | 0.733 | 0.942 | 0.593 | 0.562 | 0.758 | 0.973 |

| Hypothesis | Path Coefficient | t-Values | p-Values | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a-ECO-> Second-Order Social Capital | 0.399 | 25.209 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H1b-ETHI-> Second-Order Social Capital | 0.324 | 18.481 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H1c-LEG-> Second-Order Social Capital | 0.304 | 18.845 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H1d-PHI-> Second-Order Social Capital | 0.088 | 9.764 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2a-ECO-> Sustainable Innovation Ambidexterity | 0.093 | 1.029 | 0.304 | Not Supported |

| H2b-ETHI-> Sustainable Innovation Ambidexterity | 0.122 | 1.272 | 0.203 | Not Supported |

| H2c-LEG-> Sustainable Innovation Ambidexterity | 0.065 | 0.683 | 0.495 | Not Supported |

| H2d-PHI-> Sustainable Innovation Ambidexterity | 0.512 | 5.753 | 0.000 | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khan, A.; Chen, L.-R.; Hung, C.-Y. The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in Supporting Second-Order Social Capital and Sustainable Innovation Ambidexterity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13136994

Khan A, Chen L-R, Hung C-Y. The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in Supporting Second-Order Social Capital and Sustainable Innovation Ambidexterity. Sustainability. 2021; 13(13):6994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13136994

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Asif, Li-Ru Chen, and Chao-Yang Hung. 2021. "The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in Supporting Second-Order Social Capital and Sustainable Innovation Ambidexterity" Sustainability 13, no. 13: 6994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13136994

APA StyleKhan, A., Chen, L.-R., & Hung, C.-Y. (2021). The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility in Supporting Second-Order Social Capital and Sustainable Innovation Ambidexterity. Sustainability, 13(13), 6994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13136994