Value Creation of Business Incubator Functions: Economic and Social Sustainability in the COVID-19 Scenario

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

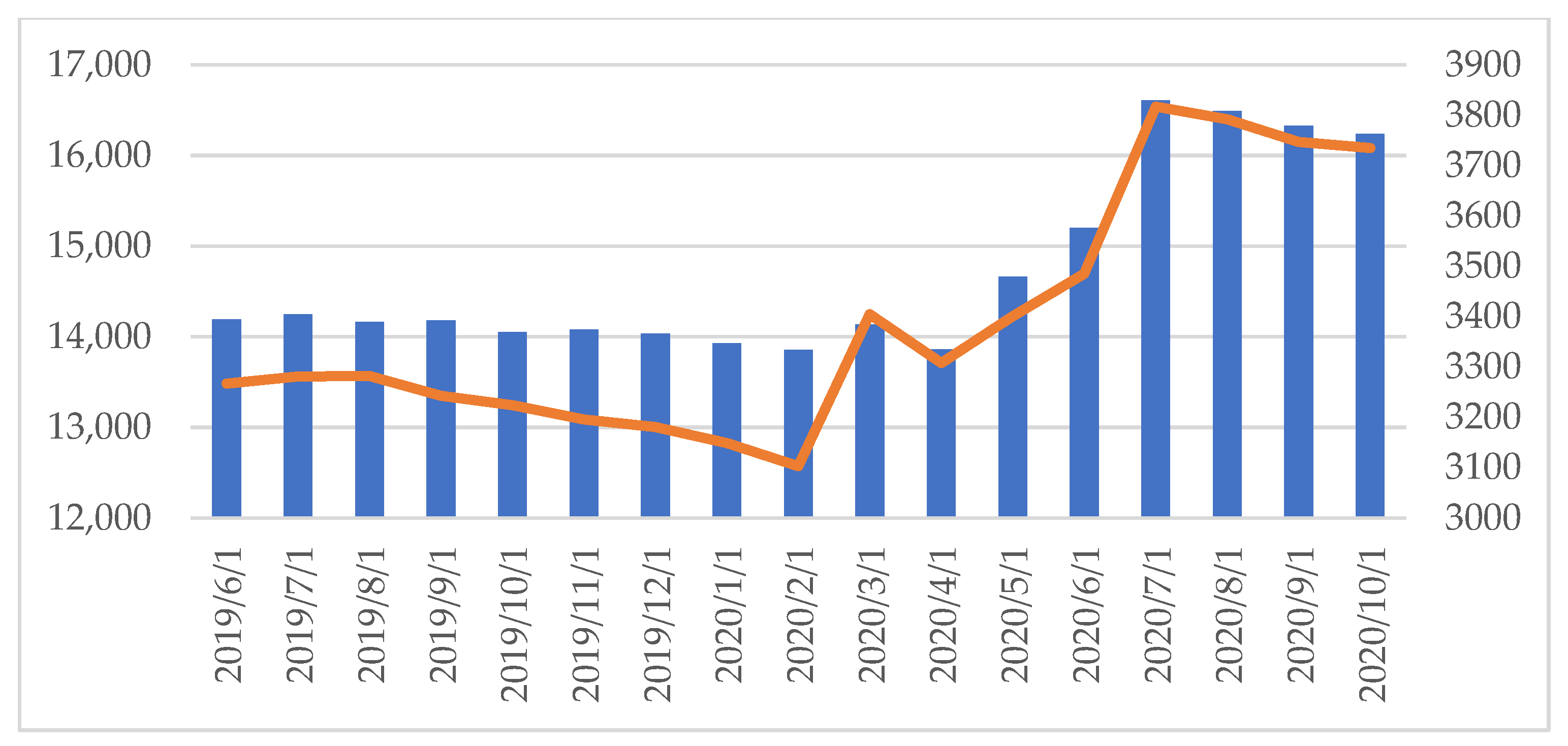

2.1. Impact of COVID-19 on Business Incubators and Entrepreneurial Activity

2.2. Hypotheses

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Methodology

Sample

4. Results

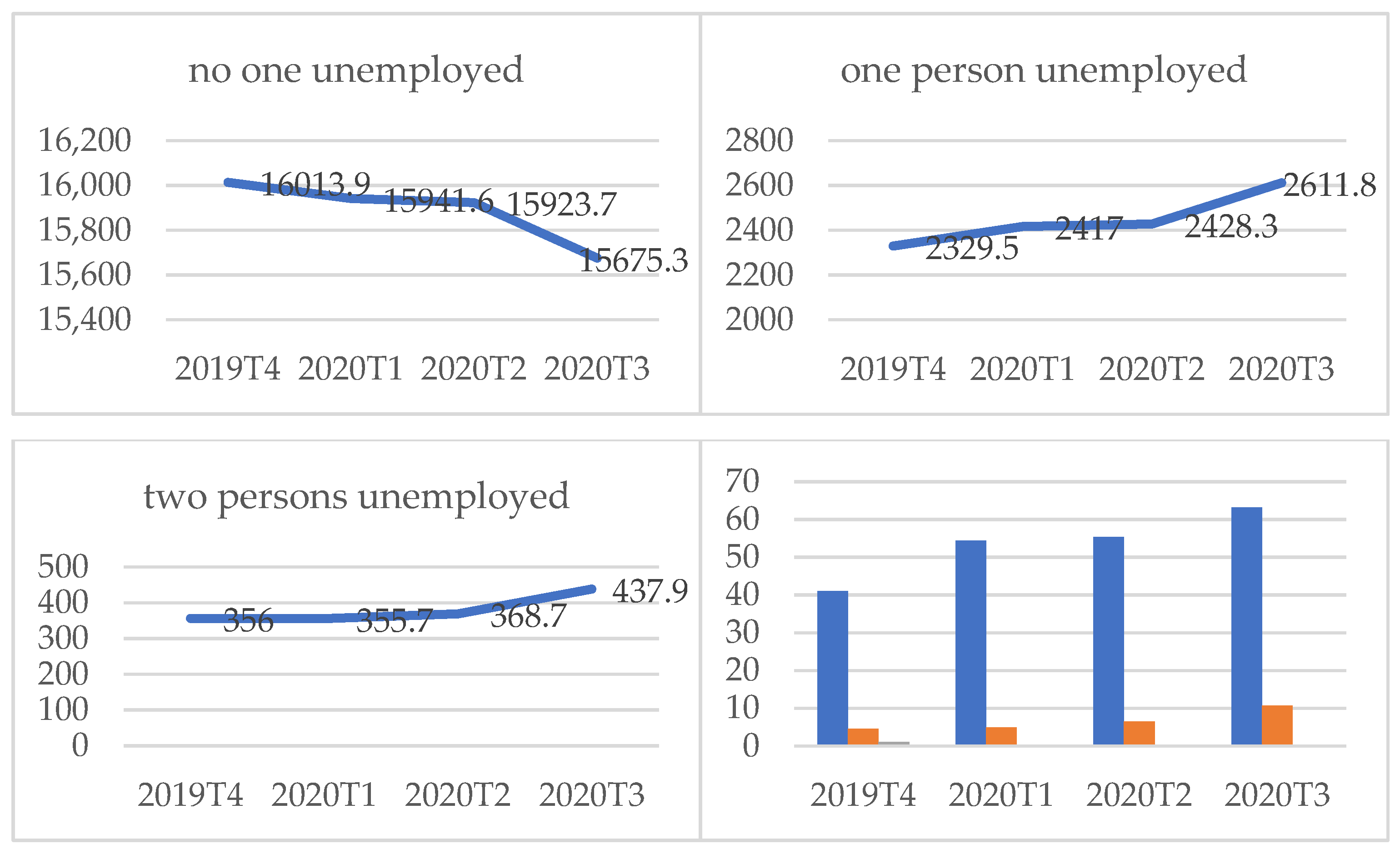

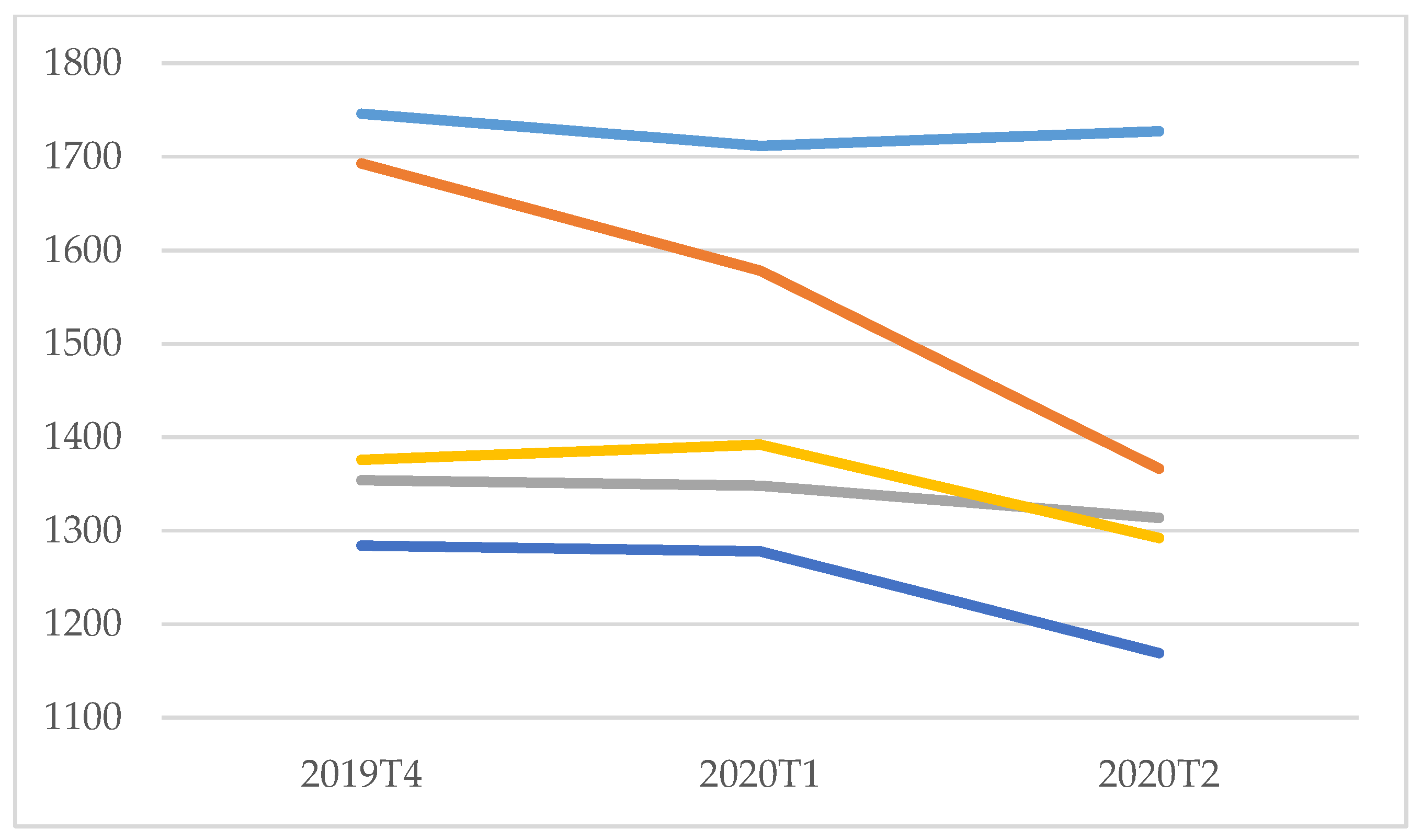

4.1. Descriptive Results

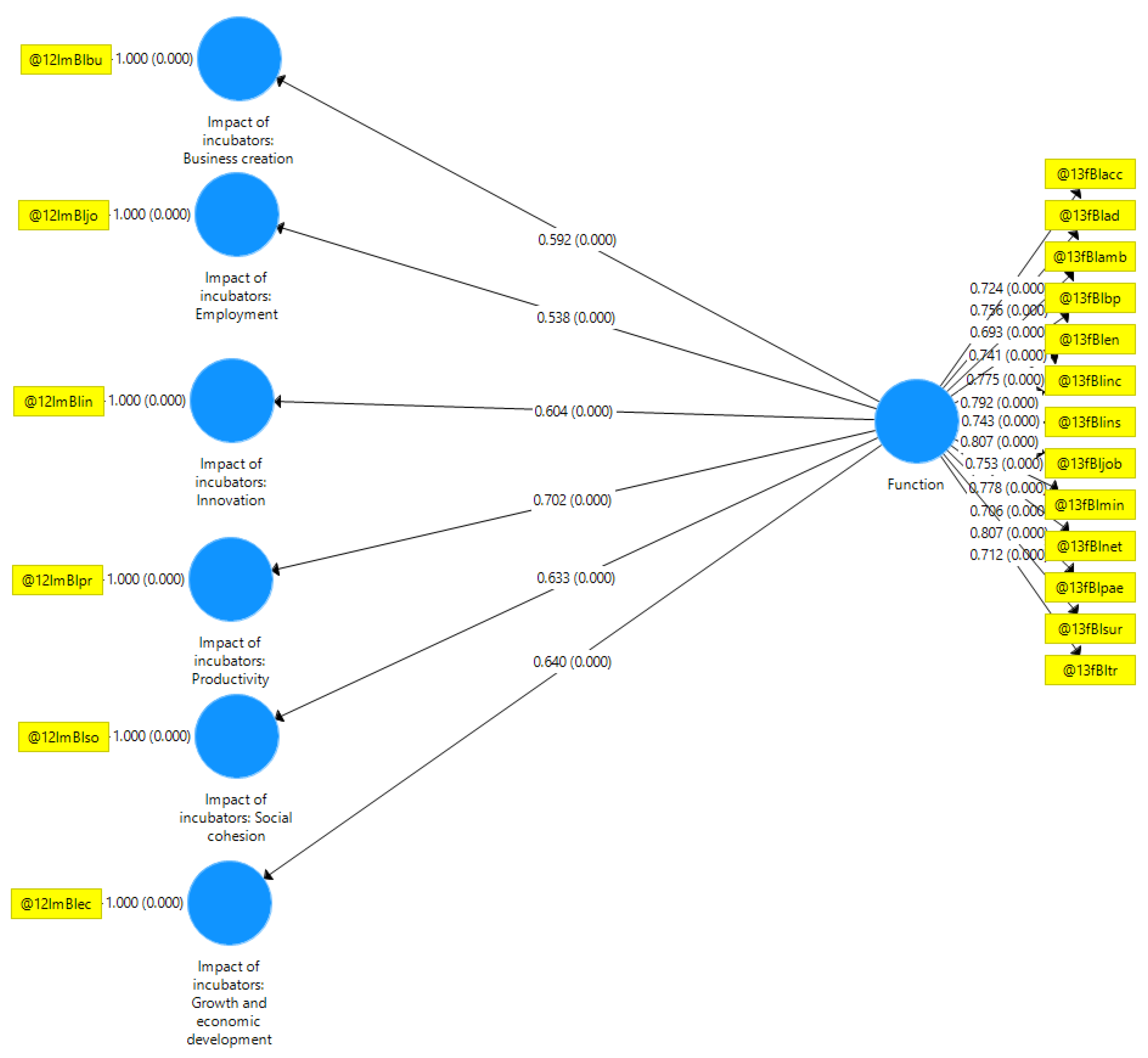

4.2. Model and Scenario Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malecki, E.J. Entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial ecosystems. Geogr. Compass 2018, 12, e12359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, F.C.; Spigel, B. Entrepreneurial ecosystems. USE Discuss. Pap. Ser. 2016, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Isenberg, D.J. How to start an entrepreneurial revolution. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2010, 88, 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- Feld, B. Startup Communities: Building an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Your City; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Acs, Z.J.; Stam, E.; Audretsch, D.B.; O’Connor, A. The lineages of the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 49, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenberg, D. The Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Strategy as a New Paradigm for Economy Policy: Principles for Cultivating Entrepreneur-Ship. Presentation at the Institute of International and European Affairs, Dublin, Ireland, 2011, 1–13. Available online: http://www.innovationamerica.us/images/stories/2011/The-entrepreneurship-ecosystem-strategy-for-economic-growth-policy-20110620183915.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Brush, C.G. Exploring the concept of an entrepreneurship education ecosystem. In Innovative Pathways for University Entrepreneurship in the 21st Century; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- García, A.V.; Seoane, F.J.F. Experiencias regionales en viveros de empresas. Rev. Estud. Reg. 2015, 102, 177–208. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco, F.J.J.; Ackerman, B.V.; Polo, C.G.O.; Fernández, M.T.F.; Santos, J.L. Los Servicios Que Prestan los Viveros de Empresas en España; Ranking 2018/2019. Funcas: Madrid, Spain, 2019. Available online: https://www.funcas.es/libro/los-servicios-que-prestan-los-viveros-de-empresas-en-espana-ranking-2018-2019-noviembre-2018/ (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Acs, Z.J.; Autio, E.; Szerb, L. National systems of entrepreneurship: Measurement issues and policy implications. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 476–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderete, R.Y.; Flores, L.E.; Mariño, S.I. Diagnóstico de Gestión del Conocimiento en una organización pública. In Proceedings of the XI Simposio Argentino de Informática en el Estado (SIE)-JAIIO, Córdoba, Spain, 4–8 September 2017; Volume 46, pp. 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- García-Ochoa, C.P.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; Jiménez, F.J.B. How business accelerators impact startup’s performance: Empirical insights from the dynamic capabilities approach. Intang. Cap. 2020, 16, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enfermedad Coronavirus (COVID-19). Organización Mundial de la Salud, 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). 2021. Available online: https://ine.es/ (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Banco de España (Eurosistema). Acciones Relacionadas Con el COVID-19. 2021. Available online: https://www.bde.es/bde/es/Home/Noticias/covid-19/ (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- Gobierno de España: Ministerio de Sanidad. Enfermedad Por Nuevo Coronavirus, COVID-19. 2021. Available online: https://www.mscbs.gob.es/ (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- Blanco, F.J.J.; Polo, C.G.O.; Fernández, M.T.F.; Santos, J.L.; de Esteban, D.E. Los Servicios que Prestan los Viveros de Empresas en España. Ranking 2020/2021. Funcas: Madrid, Spain, 2020. Available online: https://www.funcas.es/libro/los-servicios-que-prestan-los-viveros-y-aceleradoras-de-empresas-en-espana-ranking-2020-2021/ (accessed on 8 February 2021).

- European Statistical Recovery Dashboard: Eurostat. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/recovery-dashboard/ (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Roundy, P.T.; Bradshaw, M.; Brockman, B.K. The emergence of entrepreneurial ecosystems: A complex adaptive systems approach. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 86, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davila, A.; Foster, G.; Li, M. Reasons for management control systems adoption: Insights from product development systems choice by early-stage entrepreneurial companies. Account. Organ. Soc. 2009, 34, 322–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; Montes-Botella, J.L.; García-Martínez, A. Sustainability in smart farms: Its impact on performance. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Travel and Tourism Council. Economic Recovery Will be Powered by Travel & Tourism Sector Says WTTC. 2019. Available online: https://wttc.org/ (accessed on 18 March 2021).

- Ferreiro Seoane, F.J.; Mendoza Moheno, J.; Hernández Calzada, M.A. Contribución de los viveros de empresas españolas en el mercado de trabajo. Contaduría Adm. 2018, 63, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, R.; Grandi, A. Business incubators and new venture creation: An assessment of incubating models. Technovation 2005, 25, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenca, F.; Croce, A.; Ughetto, E. Business angels research in entrepreneurial finance: A literature review and a research agenda. J. Econ. Surv. 2018, 32, 1384–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo, J.M.; De Pablos, C. An analysis of the Spanish Science and Technology system. Procedia Technol. 2013, 9, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Blanco, F.J.; Guseva, V.; López, C.M. Los viveros de empresas. Economistas 2012, 30, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ayuntamiento de Madrid. Viveros de Empresas. 2021. Available online: https://www.madrid.es/ (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Sentana, E.; González, R.; Gascó, J.; LLopis, J. The social profitability of business incubators: A measurement proposal. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2017, 29, 116–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; Fernández-Valero, G.; Blanco-Callejo, M. Supplier Qualification Sub-Process from a Sustained Perspective: Generation of Dynamic Capabilities. Sustainability 2017, 9, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreiro, F.J. Mujer y emprendimiento. Una especial referencia a los viveros de empresas en Galicia. RIPS Rev. Investig. Políticas Sociológicas 2013, 12, 81–101. [Google Scholar]

- Qianqian, R.; Xindong, W. Application of Data Envelopment Analysis in Efficiency Assessment of Business Incubator: Taking Sci-Tech Business Incubators in Beijing as Example. Technol. Econ. 2011, 7, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Panorama Laboral de la Comunidad de Madrid. 2018. Available online: https://www.ucm.es/aedipi/panorama-laboral-de-la-comunidad-de-madrid (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Global Enterpreneurship Monitor. Global Enterpreneurship Monitor 2019/2020 Global Report. 2020. Available online: https://www.gemconsortium.org/report/gem-2019-2020-global-report (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Blanco-Callejo, M.; de Pablos-Heredero, C. Co-innovation at Mercadona: A radically different and unique innovation model in the retail sector. J. Bus. Retail. Manag. Res. 2019, 13, 326–341. [Google Scholar]

- Ayuntamiento de Mostoles. Mostoles Desarrollo: Viveros de Empresas. 2021. Available online: https://www.mostoles.es/ (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Ayuntamiento de Mostoles. Vivero de Empresas del Ayuntamiento de Móstoles. 2021. Available online: https://viveroempresasmostoles.es/ (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Lin, C.L. Business incubators: Mechanisms to boost business innovation capacity. Analysis of business incubators in the Community of Madrid. Esic Market Econ. Bus. J. 2020, 51, 73–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carree, M.A.; Thurik, A.R. Understanding the role of entrepreneurship for economic growth. Pap. Entrep. Growth Public Policy 2003, 1005, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlthau, C.C.; Maniotes, L.K.; Caspari, A.K. Guided Inquiry: Learning in the 21st Century: Learning in the 21st Century; Abc-Clio: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- El Hussein, M.; Hirst, S.; Salyers, V.; Osuji, J. Using grounded theory as a method of inquiry: Advantages and disadvantages. Qual. Rep. 2014, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ebbers, J.J. Networking behavior and contracting relationships among entrepreneurs in business incubators. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, I. Definición de Encuesta. Promonegocio. 2010. Available online: https://www.promonegocios.net/mercadotecnia/encuestas-definicion.html (accessed on 29 January 2021).

- Mateus, J.R.; Brasset, D. La globalización: Sus efectos y bondades. Econ. Desarro. 2002, 1, 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, A.F.S. El rol del empresario en la cohesión social. Criterio Libre 2011, 9, 127–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ortiz, P.G.; Millán, A.M.J. Emprendedores y empresa. In La Construcción Social del Emprendedor; Universidad de Murcia: Murcia, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo, M.; Camarero, C. Social Capital in University Business Incubators: Dimensions, antecedents and outcomes. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 599–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascigil, S.F.; Magner, N.R. Business incubators: Leveraging skill utilization through social capital. J. Small Bus. Strategy 2009, 20, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, M.T.; Chesbrough, H.W.; Nohria, N.; Sull, D.N. Networked incubators. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2000, 78, 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- Moriset, B. Building New Places of the Creative Economy. The Rise of Coworking Spaces; HAL Archives-Ouvertes: Lyon, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego Gómez, C.; De Pablos Heredero, C. Gestión de las relaciones con el cliente (CRM) y BIG DATA: Una aproximación conceptual y su influencia sobre el valor de los datos aplicados a la estrategia de venta. Dyna 2017, 92, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro de Lima, O.; Breval Santiago, S.; Rodríguez Taboada, C.M.; Follmann, N. Una nueva definición de la logística interna y forma de evaluar la misma. Ingeniare Rev. Chil. Ing. 2017, 25, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seoane, F.J.F.; García, A.V. Los viveros de empresas como instrumento para el emprendimiento. In Proceedings of the Actas de la 4ª Conferencia Ibérica de Emprendimiento, Pontevedra, Spain, 23–26 October 2014; Volume 28. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, A.; Anderson, R.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W. Multivariate Data Analysis; Kennesaw State University: Kennesaw, GA, USA, 2001; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.M. SmartPLS 3 [Computer Software]. SmartPLS GmbH 2015. Available online: http://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- García-Ochoa, C.P.; de Pablos Heredero, C.; Jiménez, F.B. The effects of business accelerators in new ventures’ dynamic capabilities. Harv. Deusto Bus. Res. 2021, 10, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Equation Modelling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient Alpha and the Internal Structure of Tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emprendedores. Eight Roads Ventures lanza un Fondo de 304 Millones de Euros Para ‘Start Up’ en Crecimiento. 2018. Available online: https://www.expansion.com/expansion-empleo/emprendedores/2018/03/20/5ab0d2a246163fa40e8b4621.html (accessed on 26 April 2021).

—three unemployed persons.

—three unemployed persons.  —four unemployed persons.

—four unemployed persons.

—three unemployed persons.

—three unemployed persons.  —four unemployed persons.

—four unemployed persons.

—Construction.

—Construction.  —Hospitality.

—Hospitality.  —Public Administration and Defense.

—Public Administration and Defense.  —Education.

—Education.  —Health and Social Services Activities.

—Health and Social Services Activities.

—Construction.

—Construction.  —Hospitality.

—Hospitality.  —Public Administration and Defense.

—Public Administration and Defense.  —Education.

—Education.  —Health and Social Services Activities.

—Health and Social Services Activities.

| Date | Number of Surveys | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Publication on the advisory website | From 7th to 10th April | 48 | We have spoken with the Advisory Administrator located in Madrid, where he has worked since 2016 to the present day, to publish the survey in a non-working place, with the right to publish it during a week (from Tuesday to Friday). |

| Electronic contact with different entrepreneurs | From 17th to 27th April | 74 | Contacted different entrepreneurs to ask them for help with the dissemination of the survey. |

| From 6th to 30th May | |||

| From 3rd to 30th June | |||

| Contact with consulting companies and training activities and well-known entrepreneurs | From 3rd to 28th July | 66 | Contact with two companies in Madrid: one for advice to students and another for training activities. |

| From 7th to 30th August | |||

| Contact with entrepreneurs facilitated by acquaintances | From 9th to 19th September | 6 | |

| Total: 194 |

| Function | References |

|---|---|

| Promotion of entrepreneurship | [9,48] |

| Advice and tutoring for the development of all kinds of ideas that are intended to be implemented | [9,18,34] |

| Carrying out training actions to train all people in various entrepreneurial skills | [24,32,39] |

| Support in the preparation of the Business Plan (pre-incubation service). | [8,28] |

| Advice and processing for the incorporation of the company through the Attention Point to the Entrepreneur (PAE) | [18,28] |

| Implementation of networking (relationship) activities | [28,43] |

| Project incubation: co-working space plus offices | [9,43,52] |

| Acceleration of high potential projects, also in free co-working spaces | [18,28,43,52] |

| Support new business initiatives through the provision of facilities and specialized consultancy | [18,28,33] |

| Strengthen entrepreneurship by creating an enabling environment for business development | [18,28,33] |

| Encouraging the consolidation of new businesses by minimizing costs at the start of business | [52] |

| Increasing the survival rate of enterprises during their first years of life | [18,28] |

| Contribute to the generation of employment, both wage-earning and through self-employment | [9,15,18,51] |

| Main Topic | References |

|---|---|

| Entrepreneurship | [9,15,18,28,35,55] |

| Increase in employment | [9,34,35] |

| Increase in innovation | [2,9,18,20,34,36] |

| Increase in productivity | [40,41,42] |

| Increase in cohesion | [9,18,20] |

| Promoting growth and economic development | [18,30,49,50] |

| Hypotheses | Standard Indicator | p-Value | Acceptance/Rejection of the Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Function -> ImBIbu | 0.592 | 0.000 | Acceptance |

| H2: Function -> ImBIjo | 0.538 | 0.000 | Acceptance |

| H3: Function -> ImBIin | 0.604 | 0.000 | Acceptance |

| H4: Function -> ImBIpr | 0.702 | 0.000 | Acceptance |

| H5: Function -> ImBIso | 0.633 | 0.000 | Acceptance |

| H6: Function -> ImBIec | 0.640 | 0.000 | Acceptance |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin-Lian, C.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; Montes-Botella, J.L. Value Creation of Business Incubator Functions: Economic and Social Sustainability in the COVID-19 Scenario. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6888. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126888

Lin-Lian C, De-Pablos-Heredero C, Montes-Botella JL. Value Creation of Business Incubator Functions: Economic and Social Sustainability in the COVID-19 Scenario. Sustainability. 2021; 13(12):6888. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126888

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin-Lian, Cristina, Carmen De-Pablos-Heredero, and José Luis Montes-Botella. 2021. "Value Creation of Business Incubator Functions: Economic and Social Sustainability in the COVID-19 Scenario" Sustainability 13, no. 12: 6888. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126888

APA StyleLin-Lian, C., De-Pablos-Heredero, C., & Montes-Botella, J. L. (2021). Value Creation of Business Incubator Functions: Economic and Social Sustainability in the COVID-19 Scenario. Sustainability, 13(12), 6888. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126888